Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to assess the therapeutic efficacy of Reiki therapy in alleviating anxiety.

Methods

In adherence to academic standards, a thorough search was conducted across esteemed databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, and the Cochrane Library. The primary objective of this search was to pinpoint peer-reviewed articles published in English that satisfied specific criteria: (1) employing an experimental or quasi-experimental study design, (2) incorporating Reiki therapy as the independent variable, (3) encompassing diverse patient populations along with healthy individuals, and (4) assessing anxiety as the measured outcome.

Results

The study involved 824 participants, all of whom were aged 18 years or older. Reiki therapy was found to have a significant effect on anxiety intervention(SMD=-0.82, 95CI -1.29∼-0.36, P = 0.001). Subgroup analysis indicated that the types of subjects (chronically ill individuals and the general adult population) and the dosage/frequency of the intervention (≤ 3 sessions and 6–8 sessions) were significant factors influencing the variability in anxiety reduction.

Conclusion

Short-term Reiki therapy interventions of ≤ 3 sessions and 6–8 sessions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing health and procedural anxiety in patients with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal endoscopy inflammation, fibromyalgia, and depression, as well as in the general population. It is important to note that the efficacy of Reiki therapy in decreasing preoperative anxiety and death-related anxiety in preoperative patients and cancer patients is somewhat less consistent. These discrepancies may be attributed to individual pathophysiological states, psychological conditions, and treatment expectations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-024-01439-x.

Keywords: Reiki therapy, Anxiety, Quality of life, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Individuals undergoing hospital examinations may experience preoperative anxiety, stress, and fear due to concerns about the examination procedure, diagnostic results, discomfort during the procedure (such as vomiting, nausea, swelling, and pain), and potential associated risks [1, 2]. Procedural anxiety, defined as the anxious and uneasy emotions experienced when encountering specific procedures or processes, can stem from uncertainty, fear, or concern about upcoming medical procedures [3]. Preoperative anxiety is a common manifestation of procedural anxiety, leading to heightened stress and anxiety in patients before medical examinations and potentially impacting the examination process, posing challenges for healthcare providers [4, 5]. Individuals with chronic pain are more prone to developing psychiatric comorbidities compared to the general population [6], with chronic pain closely linked to depression [7] and symptoms of health anxiety [8]. While death is an inevitable part of life, its uncertain nature can evoke feelings of anxiety [9, 10]. Patients facing incurable illnesses directly face mortality [11], and those diagnosed with late-stage diseases like cancer may experience heightened anxiety related to death [12]. The field of psychiatry encompasses various types of anxiety disorders, presenting multiple avenues for complementary therapies to aid in anxiety management.

Reiki, a contemporary spiritual energy therapy reintroduced by Mikao Usui in late 19th-century Japan, involves channeling healing energy through the body’s chakras [13]. Chakras, the energy centers that regulate the body’s energy, are situated along the spine and support energy circulation throughout the body [14]. In Reiki, the focused transmission of healing energy aims to address imbalances in energy fields linked to physical, emotional, or psychological sources of distress [15, 16]. Reiki is viewed as a technique to harmonize the body, mind, and spirit by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system [17, 18]. Reiki, an ancient Japanese practice, can be applied at home or remotely, utilizing intentional guided healing energy [19]. This natural therapy involves transmitting energy to the basic seven chakras, including the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and groin. The energy is transmitted through direct touch or non-contact, with each chakra receiving 3 to 5 min of attention [20]. Despite its historical roots, Reiki has gained popularity among more than 1.5 million Americans and continues to attract new practitioners [21]. In contemporary society, there is a growing emphasis on improving quality of life, reducing fatigue, and managing anxiety. These aspects play a crucial role in overall well-being, encompassing physical health, mental well-being, and the broader impact of social and environmental factors. Many individuals experience increasing levels of fatigue and stress due to work demands, family pressures, and societal expectations as they strive for personal and professional success. These challenges can have detrimental effects on both physical and mental health, contributing to conditions like anxiety and depression. Reiki, as an energy-based touch therapy, offers a means to rebalance and revitalize the body’s energy system when it is disrupted by stress or negative emotions [22].

Reiki, a low-risk and cost-free method, has shown to improve anxiety and stress reduction, as well as enhance overall quality of life [23, 24]. Some studies suggest that integrating Reiki therapy into holistic care can address the interconnectedness of body, mind, and soul, contributing to overall well-being. It could also be a valuable independent function provided by nurses [25, 26]. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine categorizes Reiki as a biofield therapy and energy therapy [27]. Traditional medical treatments, such as drug therapy, can be costly and come with potential side effects that may hinder both physical pain relief and psychological anxiety alleviation [28]. As a result, many patients can benefit from alternative and complementary therapeutic approaches alongside traditional surgical and drug treatments. Reiki, which translates to universal life energy, is an affordable, side-effect-free, and easily applicable complementary and integrative therapy. Previous meta-analyses have investigated the effects of Reiki on pain in both cancer patients and the general population, demonstrating a decrease in patient suffering [28, 29]. Expanding on this research, the objective of this study is to conduct a systematic review on the impact of Reiki on patient anxiety.

Materials and methods

Study design

This article presents a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [30]. The protocol for this review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) before screening search results (Registration Number: CRD42023483969), and the reporting of the study adheres to the PRISMA statement.

Study inclusion criteria

This study includes controlled trials (RCTs) of Reiki therapy with a minimum of one session. The Reiki therapy should be compared with a placebo group or blank control. The participants in the selected studies should be adults (aged 18 years or older) without any restrictions based on gender, race, or socioeconomic background. The study can involve various types of patients such as gastrointestinal endoscopy patients, cancer patients, surgery patients, chronic disease patients, and depression patients, as well as normal adults. The anxiety levels will be assessed using anxiety scales in the eligible studies. Only studies in English and in full-text format will be considered. Descriptive reviews, preclinical studies, duplicate studies, editorials or opinion articles, grey literature, and conference papers will not be included. Systematic reviews and study protocols that do not meet the inclusion criteria will be evaluated as guidelines and cited when appropriate.

Search strategy

This meta-analysis aimed to assess the effectiveness of Reiki therapy in reducing anxiety. Searches were conducted in the PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library databases from January 1, 2005, to November 11, 2023, to ensure a comprehensive selection of relevant studies. The search terms included ‘Reiki therapy’ OR ‘Reiki intervention’ AND ‘Anxiety’ AND (‘Controlled Trial’ OR ‘Randomized Controlled Trial’ OR ‘Clinical Trial’ OR ‘Controlled Study’ OR ‘Comparative Study’ OR ‘Placebo-Controlled Trial’) AND (‘Procedural Anxiety’ OR ‘Health Anxiety’ OR ‘Death Anxiety’).

Study selection process

Search results were imported into Zotero 6.0. After removing duplicates, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the studies. Studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. Full texts of all relevant studies were obtained, downloaded, and further assessed for eligibility. Any disagreements between the two reviewers regarding the inclusion of specific studies were resolved through consultation with a third independent reviewer to minimize bias in the decision of whether to include certain studies. Data extraction was independently performed by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consulting the aforementioned third independent reviewer.

Data extraction

The data extracted from the selected studies covered various areas including authorship, publication year, sample size, participant age and gender, study design, intervention description (including method, frequency and duration, and key components), control group, outcome measures and time points, results, dropout rates, and handling of missing data.

Effect size measurement

The inclusion criteria for study outcomes involved evaluating the average difference between the Reiki therapy intervention group and the control group at the assessment endpoint. Data were extracted and recorded independently by two authors, with any discrepancies resolved through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer. Manuscripts were included in the meta-analysis only if the results of the anxiety scale were adequately reported.

Data synthesis

Using the Der Simonian-Laird random-effects and fixed-effects models (depending on heterogeneity) and STATA software (version 15), we calculated the summary values of the weighted mean differences between the Reiki treatment group and the control group. We also calculated the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The effect size estimation was weighted by the inverse of its variance, and we used Hedges’ g statistic to calculate the effect size of the standardized mean difference and its corresponding 95% CI. Hedges’ g size interpretations were as follows: small (g = 0.3), medium (g = 0.5), and large (g = 0.8). To assess heterogeneity, we used the chi-square test to evaluate the null hypothesis that all studies assessed the same effect. We quantified the total variation consistent with heterogeneity among studies using the inconsistency index (i.e., I2), which ranges from 0 to 100%. We considered a p-value < 0.10 from the chi-square test and I2 > 50% as signs of significant heterogeneity [31]. We generated a funnel plot, using the effect size for each trial against standard error, to assess potential publication bias. The asymmetry of the funnel plot was evaluated through Egger’s small-sample effect test based on regression.

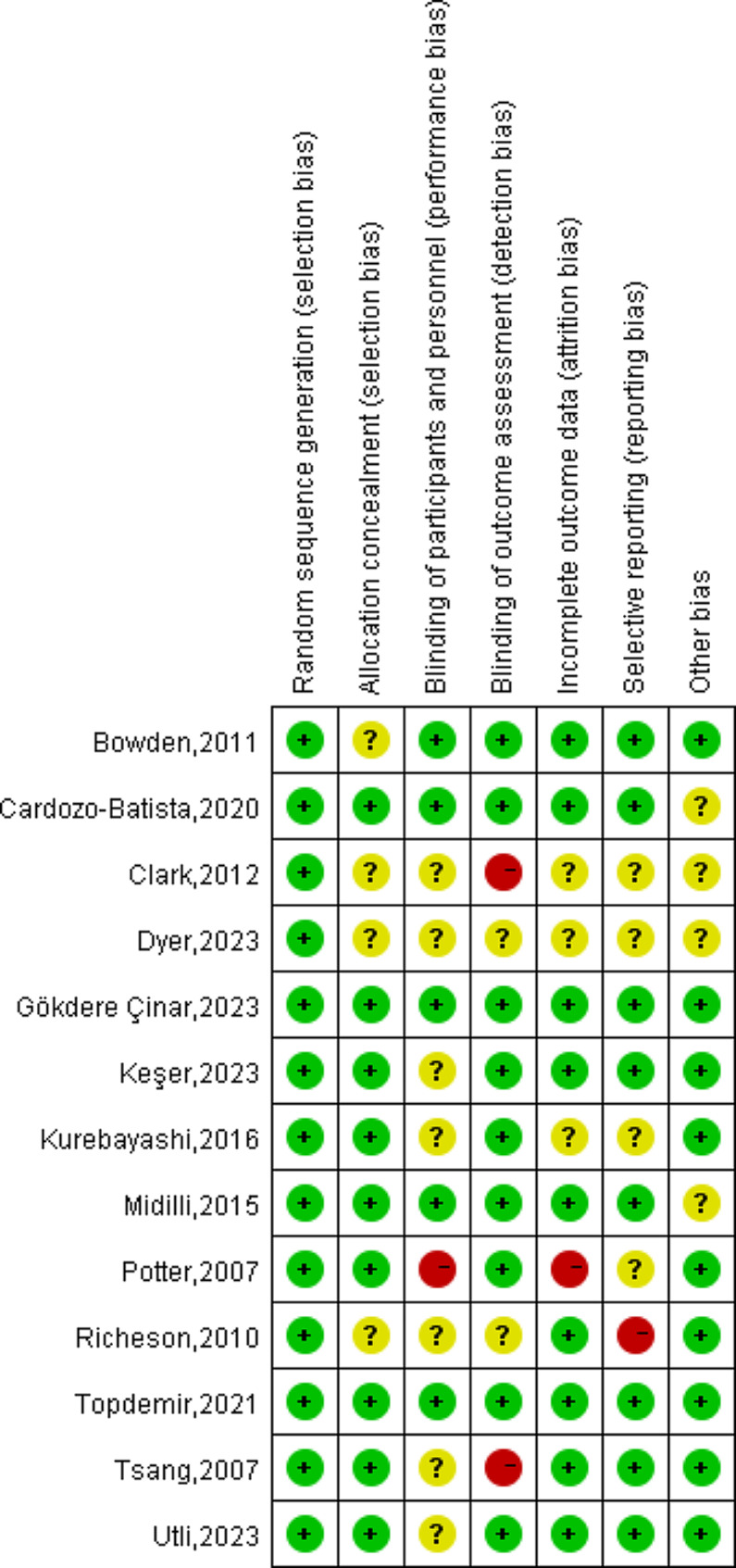

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

The quality of each included study was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, which evaluated random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases [32]. Two authors independently conducted the quality assessments, and any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer.

Results

Study selection

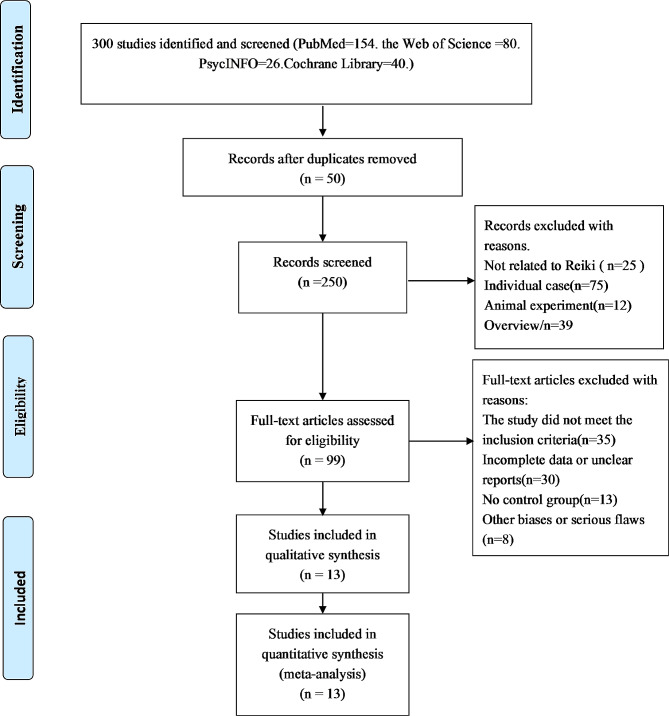

A total of 300 articles were initially identified from four databases, with 50 duplicates. After screening the titles and abstracts of 250 articles, 151 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 99 articles that met the criteria underwent a full-text review. Out of these, 86 articles were excluded, and the reasons for their exclusion are detailed in Fig. 1. Ultimately, this systematic review included 13 studies [13, 23, 33–43].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study

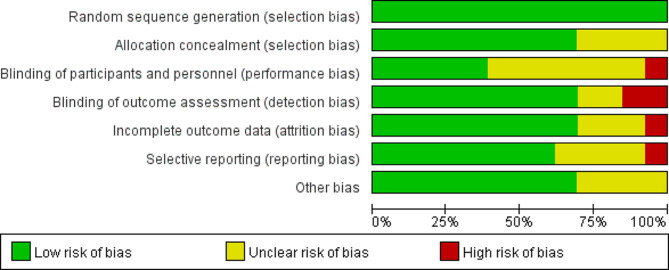

Risk of bias of included studies

All studies included in this review adequately described the generation of random allocation sequences, indicating a low risk of selection bias associated with sequence generation. Nine trials provided specific details on maintaining the confidentiality of sample allocation, categorizing them as low risk [13, 23, 33, 35–39, 41]. However, the remaining studies lacked detailed descriptions of procedures and clear information, leading to an unclear classification. Regarding performance bias, the nature of these trials made blinding of participants or Reiki practitioners challenging [23, 33–35, 37, 38, 40, 43]. However, it is crucial to blind the outcome assessment in Reiki intervention studies. Nevertheless, four studies reported measures taken for blinding outcome assessment, while for the remaining, it was unclear or not specified [23, 34, 40, 43]. The assessment of attrition and reporting bias was heavily influenced by these two studies [40, 43]. A summary and a graph of the risk of bias are provided in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias graph

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of 13 controlled experimental studies involving a total of 824 participants, which investigate the effectiveness of Reiki therapy for treating anxiety. Notably, a larger number of studies have been conducted in the United States [34, 35, 40, 43] and Turkey [13, 33, 36, 38, 39] on the application of Reiki therapy. This paper assesses the selected studies based on their research goals, study features, outcome measures, and main findings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis

| Author/Year | Author’s country | Research design | Sample size (T/C) | Age range | Subject type | Intervention design (T/C) | Exercise prescription | Evaluation tools/content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utli,2023 [33] | Turkey | RCT | 53/53 | 49.6 ± 10.2 | Chronically ill | Reiki/Control group | 25 min/times, 1 / week, 1 week | SAI |

| Tsang,2007 [23] | Canada | RCT | 8/8 | 59 ± 15.23 | Cancer patient | Reiki/Control group | 45 min/times, 5 / week, 1 week | Esas |

| Topdemir,2021 [13] | Turkey | RCT | 105/105 | 36.67 ± 13.62 | Surgical patient | Reiki/Control group | 60 min/times, 2 / week, 1 week | STAI |

| Richeson,2010 [34] | America | RCT | 12/8 | Community elderly | Community elderly | Reiki/Control group | 45 min/times, 1 / week, 8 weeks | HAM-A |

| Potter,2007 [35] | America | RCT | 17/15 | Middle age women | Middle age women | Reiki/Control group | 50 min/times, 2 / week, 1 week | STAI |

| Midilli,2015 [36] | Turkey | RCT | 45/45 | 18–45 | Surgical patient | Reiki/Control group | 30 min/times, 2 / week, 1 week | SAI |

| Kurebayashi,2016 [37] | Brazil | RCT | 38/33 | 18–45 | Normal adult | Reiki + massage/Control group | 45 min/times, 2 / week, 4 weeks | IDATE |

| Keşer,2023 [38] | Turkey | RCT | 34/33 | 37.47 ± 10.45 | Chronically ill | Reiki/Control group | 20 min/times, 2 / week, 1 week | SAS |

| Gökdere Çinar,2023 [39] | Turkey | RCT | 25/25 | 43.56 ± 9.52 | Chronically ill | Reiki/Control group | 30 min/times, 1 / week, 4 weeks | STAI |

| Dyer,2023[41] | America | RCT | 40/39 | 35.56 ± 9.32 | Normal adult | Reiki/Control group | 20 min/times, 4 / week, 1 week | MYMOP |

| Cardozo-Batista,2020 [41] | Brazil | RCT | 10/11 | Medical staff | Chronically ill | Reiki/Control group | 65 min/times, 1 / week, 8 weeks | DASS-21 |

| Bowden,2011 [42] | Britain | RCT | 20/20 | 39.4 ± 10.36 | Normal adult | Reiki/Control group | 30 min/times, 6 / week, 4 weeks | HADS |

| Clark,2012 [43] | America | RCT | 7/5 | 59.04 ± 8.56 | Cancer patient | Reiki/Meditation | 60 min/times, 1 / week, 6 weeks | QLN |

Notes: Intervention Group (T); Control Group (C); Randomized controlled trial (RCT); State Anxiety Inventory (SAI); Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A); State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A); State Anxiety Scale (SAI); Trace State Anxiety Inventory (IDATE); State Anxiety Subscale (SAS); Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP); Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Quality of life and neurotoxicity(QLN);

Meta-analysis

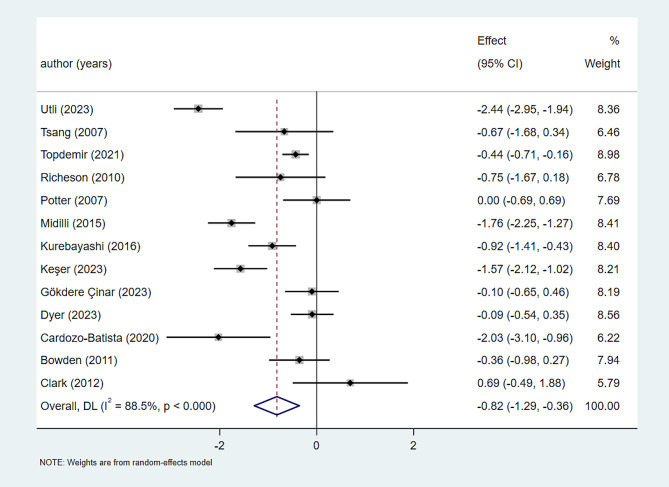

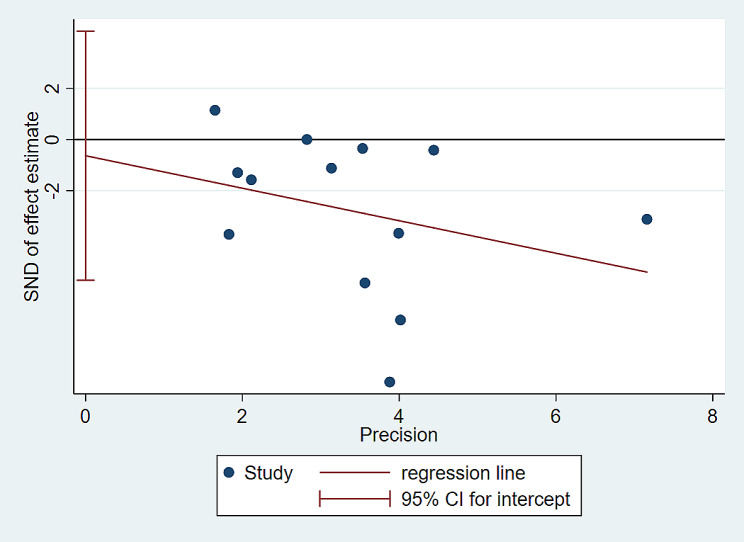

In this systematic evaluation, we assessed a total of 13 studies [13, 23, 33–43] involving 824 patients to evaluate the effects of Reiki therapy on anxiety relief. We observed considerable heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 88.5%, P < 0.000), which led us to use a random-effects model for analysis. The results showed a significant impact of Reiki therapy on anxiety intervention(SMD=-0.82, 95CI -1.29∼-0.36, P = 0.001). Refer to Fig. 4 for a graphical representation. As I2 > 50% (I2 = 88.5%, P < 0.000), we performed an Egger regression to detect publication bias. Egger regression is a statistical method used to evaluate if study outcomes are influenced by the small sample effect [44]. The results of the Egger test (t=-0.29, P = 0.779) indicated no evidence of publication bias. Please refer to Fig. 5 for more details.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of Reiki therapy in the intervention of anxiety

Fig. 5.

Publication bias plot of Reiki therapy in the intervention of anxiety

Subgroup analysis

To investigate the factors influencing the effectiveness of Reiki therapy in alleviating anxiety, subgroup analyses were conducted based on different patient types, intervention durations, and intervention frequencies.

Subgroup analysis results on anxiety indicate that factors such as the type of subjects (chronically ill individuals and the general adult population) and the dosage/frequency of intervention (≤ 3 and 6–8 sessions) significantly contribute to the heterogeneity affecting anxiety relief. Please refer to Table 2 for more details. Short-term interventions (≤ 3 sessions) and moderate-frequency Reiki therapy (6–8 sessions) have shown effectiveness in alleviating health and procedural anxiety in patients with chronic conditions (e.g., those undergoing gastrointestinal endoscopy, fibromyalgia, and depression) and the general adult population. However, it is important to note that the effectiveness of Reiki therapy in reducing preoperative and death anxiety in preoperative and cancer patients is relatively lower.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis results of Reiki therapy in the treatment of anxiety

| Dimensionality | sort | Number of studies/papers | I2 | Effect model | SMD and 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject type | Chronically ill | 4 | 95% | Random | -1.75(-3.20,-0.29) | 0.018 |

| Surgical patient | 2 | 95.3% | Random | -1.08(-2.38,0.21) | 0.102 | |

| Cancer patient | 2 | 65.8% | Random | -0.03(-1.36,1.31) | 0.970 | |

| Normal adult population | 4 | 49.7% | Fix | -0.41(-0.79,-0.03) | 0.035 | |

| Intervention time/minute | ≤ 30 | 6 | 93.3% | Random | -1.06(-1.88,-0.23) | 0.012 |

| 45–60 | 7 | 64.4% | Random | -0.58(-1.02,-0.15) | 0.009 | |

| Intervention dose/frequency | ≤ 3 | 5 | 94.2% | Random | -1.25(-2.12,-0.38) | 0.005 |

| 4–6 | 5 | 0.0% | Fix | -0.15(-0.43,0.13) | 0.289 | |

| 6–8 | 3 | 48.6% | Fix | -1.13(-1.77,-0.49) | 0.001 |

Discussion

This systematic review includes 13 studies [13, 23, 33–43], which evaluate the effectiveness of Reiki therapy in reducing anxiety among 824 patients. The results show a significant impact of Reiki intervention on anxiety(SMD=-0.82, 95CI -1.29∼-0.36, P = 0.001). Overall, short-term interventions (≤ 3 sessions) and moderate-frequency Reiki treatments (6–8 sessions) have shown effectiveness in reducing health and procedural anxiety in patients with chronic conditions (such as those undergoing gastrointestinal endoscopy, fibromyalgia, and depression) as well as in the general adult population. Previous meta-analyses have investigated the effects of Reiki on pain relief. Avci et al. [28] conducted a meta-analysis of 7 relevant studies, concluding that the use of Reiki can decrease pain levels in cancer patients. In a similar vein, Thrane et al. [45] examined 20 studies and found evidence that Reiki can help alleviate pain. Anxiety, as defined by the American Psychological Association, is marked by physiological reactions such as fear, anxious thoughts, and increased blood pressure [46]. In the context of mitigating anxiety and stress levels, Reiki, a complementary energy therapy, has been found to enhance pharmacological treatments [36]. Various reviews, such as those conducted by Billot et al., have demonstrated the efficacy of Reiki in reducing anxiety across diverse groups. These groups encompass a range of individuals, from those in good health to individuals experiencing chronic pain, post-hysterectomy patients, women undergoing breast biopsies, stage I to IV cancer patients, and older adults living in the community. Nonetheless, a single study indicates that Reiki may not have a significant impact on anxiety levels in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy [18, 47–51]. Gastroscopy, an invasive procedure that can induce anxiety in some individuals due to the discomfort of a foreign object in their body, often deters people from undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, resulting in missed examinations [52]. Reiki has been shown as an adjunctive sedative treatment to help alleviate pre-gastroscopy anxiety, reducing the need for sedatives, lowering the risk of complications, and enhancing patient safety [33]. Fibromyalgia, a chronic syndrome characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain and tender points [53], was treated with Reiki therapy by Gökdere Çinar et al. The study reported positive effects including pain relief, improved quality of life, and reduced trait anxiety levels [39]. Richeson et al. [34] investigated the efficacy of Reiki as a complementary treatment for pain, depression, and anxiety in community-dwelling elderly individuals. Their findings revealed significant improvements in symptom relief, suggesting that Reiki may be a beneficial intervention for this population. Additionally, previous studies have shown that Reiki can reduce anxiety and depression in college students [42] and adolescents [54]. Overall, the use of Reiki as an adjunct therapy has shown promise in alleviating pain and anxiety in diverse populations.

Clark et al. [43] discovered that Reiki had positive impacts on psychological distress and quality of life in patients with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Tsang et al. [23] explored the potential benefits of Reiki in reducing cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and enhancing overall well-being in cancer patients. Their results indicated that Reiki had a moderate effect on reducing CRF and significantly improving fatigue levels, daily pain, anxiety, and overall quality of life. Topdemir et al. have conducted a study with preoperative patients, where the experimental group showed no change in state anxiety scores, while the control group experienced an increase in state anxiety scores [13]. A small-scale pilot study with blinding and placebo control demonstrated that Reiki could reduce anxiety levels in hospitalized patients undergoing surgical treatment [55]. Additionally, Cassidy et al. [56] conducted a study and found that combining Reiki with music significantly decreased preoperative anxiety in patients when compared to the use of music alone. The subgroup analysis conducted in this study revealed that Reiki therapy did not show a statistically significant reduction in anxiety among cancer patients and preoperative patients. This variance could be linked to individual pathological and physiological conditions, psychological states, and treatment expectations. It is advisable to conduct additional research specifically targeting Reiki therapy in cancer and preoperative patients to delve into its effectiveness within these particular groups and examine possible influencing factors, including patients’ beliefs, attitudes, and the severity of their conditions. The duration of the intervention also plays a role in anxiety relief. Olsen et al. found that the Reiki group had a moderate effect on pain reduction on the first day [24]. Thrane et al. [45] suggested that interventions lasting 26 weeks or longer could highlight differences between the Reiki group and the sham Reiki group. These results align with the subgroup analysis in this study, showing that short-term interventions (≤ 3 times) and 6–8 sessions of Reiki therapy yield positive outcomes for anxiety relief.

Limitations

This systematic evaluation of Reiki therapy for anxiety relief acknowledges certain inherent limitations. The limited number of studies prevented a meta-analysis for a specific population, prompting the exploration of factors influencing treatment effects through subgroup analysis. Notably, fewer controlled studies were available for cancer patients in the subgroup analysis, potentially impacting the results. The parameters used for grouping in the subgroup analysis had limitations in identifying factors influencing intervention effects. Additionally, this review only considered English-language controlled experiments, possibly excluding pertinent literature published in other languages.

Conclusions

From an integrative perspective, research has shown that short-term interventions (≤ 3 sessions) and moderate-frequency Reiki therapy (6–8 sessions) can effectively reduce health and procedural anxiety in patients with chronic conditions like gastrointestinal endoscopy, fibromyalgia, and depression, as well as in the general adult population. It is important to note that the effectiveness of Reiki therapy in reducing preoperative and death anxiety in preoperative patients and cancer patients appears to be lower. Further studies focusing on Reiki therapy in cancer and preoperative patients are recommended to better understand its effects in these specific populations and explore potential influencing factors, such as patients’ beliefs, attitudes, and disease severity.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Guo Xiulan

(1987-), female, born in Weifang, Shandong Province, master’s degree, lecturer. Her research interests include physical education and training.

Author contributions

X.L., Z.K., and Y.T. primarily wrote the first draft. L.Y. was mainly responsible for data collection. X.L. was primarily responsible for guidance and methodology.

Funding

There was no funding for this investigation.

Data availability

All data and materials can be accessed by contacting the first author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

There was no ethics approval necessary because this is a review of the literature.

Consent for publication

All authors gave consent for the publication. Study participants agreed to publish their identifiable data in an online open access journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhikai Qin, Email: aa15518619819@163.com.

Yongtao Fan, Email: 13655040822@163.com.

References

- 1.Shaermoghadam S, Shahdadi H, Khorsandvakilzadeh A, Afshari M, Badakhsh M. Comparison of the effects of foot and hand reflexology massages on stress and anxiety in candidate patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;8:1254–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ceyhan Ö, Tekinsoy Kartın P, Taşcı S. Effect of anxiety evel of education in patients of endoscopy. Pam Med J. 2018;11:293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badner NH, Nielson WR, Munk S, Kwiatkowska C, Gelb AW. Preoperative anxiety: detection and contributing factors. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:444–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03005624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Analysis of patients Attitude to undergo urgent endoscopic procedures during COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Dig Liver Disease. 2020;52:695–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sogabe M, Okahisa T, Adachi Y, Takehara M, Hamada S, Okazaki J, et al. The influence of various distractions prior to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:132. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0859-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raphael KG, Janal MN, Nayak S, Schwartz JE, Gallagher RM. Psychiatric comorbidities in a community sample of women with fibromyalgia. Pain. 2006;124:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bravo L, Mico JA, Rey-Brea R, Pérez-Nievas B, Leza JC, Berrocoso E. Depressive-like states heighten the aversion to painful stimuli in a rat model of comorbid chronic pain and depression. J Am Soc Anesthesiologists. 2012;117:613–25. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182657b3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan KD, Okifuji A. Anxiety disorders: Differential diagnosis and their relationship to Chronic Pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharm. 2011;25:231–45. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2011.596922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neel C, Lo C, Rydall A, Hales S, Rodin G. Determinants of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Supportive Palliat Care. 2015;5:373–80. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asadzandi M, Taghizade Karati K, Tadrisi S, Abbas E. Effect of prayer on severity of patients illness in intensive care units. Iran J Crit Care Nurs. 2011;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohammadzadeh A, Ashouri A. The study of some Religious correlates of Death Depression among University Stu-dents. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2017;23:68–77. doi: 10.18869/nirp.ijpcp.23.1.68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdollahi A, Panahipour H, Allen KA, Hosseinian S. Effects of death anxiety on perceived stress in individuals with multiple sclerosis and the role of self-transcendence. Omega (Westport) 2021;84:91–102. doi: 10.1177/0030222819880714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topdemir EA, Saritas S. The effect of preoperative Reiki application on patient anxiety levels. EXPLORE. 2021;17:50–4. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster LC, Holden JM, Ray DC, Price E, Hastings TM. The impact of psychotherapeutic reiki on anxiety. J Creativity Mental Health. 2020;15:311–26. doi: 10.1080/15401383.2019.1688214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyer NL, Baldwin AL, Rand WL. A large-scale effectiveness trial of Reiki for Physical and Psychological Health. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25:1156–62. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bat N. The effects of reiki on heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and stress levels: a pilot randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;43:101328. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erdoğan Z, ÇINAR S. Reiki: An ancient healing art-modern nursing practice. Kafkas Journal of Medical Sciences. 2011;2:86–91.

- 18.Vitale A. An Integrative Review of Reiki Touch Therapy Research. Holist Nurs Pract. 2007;21:167. doi: 10.1097/01.HNP.0000280927.83506.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.vanderVaart S, Berger H, Tam C, Goh YI, Gijsen VMGJ, de Wildt SN, et al. The effect of distant reiki on pain in women after elective caesarean section: a double-blinded randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000021. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Özcan Yüce U, Taşcı S. Effect of Reiki on the stress level of caregivers of patients with cancer: qualitative and single-blind randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2021;58:102708. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2021.102708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. 2008;4:11–23. [PubMed]

- 22.Chang SO. Meaning of Ki related to touch in caring. Holist Nurs Pract. 2001;16:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsang KL, Carlson LE, Olson K. Pilot crossover trial of Reiki Versus Rest for Treating Cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:25–35. doi: 10.1177/1534735406298986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson K, Hanson J, Michaud M. A phase II trial of reiki for the management of pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;26:990–7. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birocco N, Guillame C, Storto S, Ritorto G, Catino C, Gir N, et al. The effects of Reiki Therapy on Pain and anxiety in patients attending a day oncology and infusion services unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:290–4. doi: 10.1177/1049909111420859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pocotte SL, Salvador D. Reiki as a rehabilitative nursing intervention for pain management: a case study. Rehabilitation Nurs J. 2008;33:231–2. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2008.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potter PJ. Energy therapies in Advanced Practice Oncology: an evidence-informed Practice Approach. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013;4:139–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avci A, Gün M. The Effect of Reiki on Pain Applied to patients with Cancer: a systematic review. Holist Nurs Pract. 2023;37:268–76. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demir Doğan M. The effect of reiki on pain: a meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:384–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau J, Ioannidis JPA, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;4:320–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Utli H, Doğru BV. The Effect of Reiki on anxiety, stress, and comfort levels before gastrointestinal endoscopy: a randomized sham-controlled trial. J PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 2023;38:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2022.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richeson NE, Spross JA, Lutz K, Peng C. Effects of Reiki on anxiety, Depression, Pain, and physiological factors in Community-Dwelling older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3:187–99. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20100601-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter PJ. Breast biopsy and distress: feasibility of testing a Reiki intervention. J Holist Nurs. 2007;25:238–48. doi: 10.1177/0898010107301618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Midilli TS, Eser I. Effects of Reiki on Post-cesarean Delivery Pain, anxiety, and hemodynamic parameters: a Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Manage Nurs. 2015;16:388–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurebayashi LFS, Turrini RNT, Souza TPBD, Takiguchi RS, Kuba G, Nagumo MT. Massage and Reiki used to reduce stress and anxiety: Randomized Clinical Trial. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2016; 8:24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Keşer E, Bağlama SS, Sezer C. The Effect of Reiki and aromatherapy on vital signs, Oxygen Saturation, and anxiety level in patients undergoing Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: a randomized controlled study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2023;37:337–46. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gökdere Çinar H, Alpar Ş, Ilhan S. Evaluation of the impacts of Reiki Touch Therapy on patients diagnosed with Fibromyalgia who are followed in the Pain Clinic. Holist Nurs Pract. 2023;37:161–71. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dyer NL, Baldwin AL, Pharo R, Gray F. Evaluation of a Distance Reiki Program for Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Health-Related Quality of Life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Adv Integr Med Health. 2023;12:27536130231187368. doi: 10.1177/27536130231187368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cardozo-Batista L, Tucci AM. Effectiveness of an alternative intervention in the treatment of depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:562–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowden D, Goddard L, Gruzelier J. A randomised controlled single-blind trial of the efficacy of Reiki at Benefitting Mood and Well-Being. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2011;2011:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2011/381862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark PG, Cortese-Jimenez G, Cohen E. Effects of Reiki, yoga, or Meditation on the physical and psychological symptoms of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: a Randomized Pilot Study. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;17:161–71. doi: 10.1177/2156587212450175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson L, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane database of systematic reviews; 2012; 9:17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Thrane S, Cohen SM. Effect of Reiki Therapy on Pain and anxiety in adults: an In-Depth literature review of Randomized trials with effect size calculations. Pain Manage Nurs. 2014;15:897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Cabana M, Coker TR, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;328:1438–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Billot M, Daycard M, Wood C, Tchalla A. Reiki therapy for pain, anxiety and quality of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019; 9:434–438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Lee MS, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Effects of reiki in clinical practice: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:947–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Billot M, Daycard M, Wood C, Tchalla A. Reiki therapy for pain, anxiety and quality of life. BMJ Supportive Palliat Care. 2019;9:434–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.vanderVaart S, Gijsen VMGJ, De Wildt SN, Koren G. A systematic review of the Therapeutic effects of Reiki. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:1157–69. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McManus DE. Reiki is Better Than Placebo and Has Broad Potential as a complementary health therapy. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;22:1051–7. doi: 10.1177/2156587217728644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Özer N, Ergen H. The effect of progressive relaxation exercises on pain perception and vital signs in patients who underwent endoscopy. Laparosc Endoscopic Surg Sci (LESS) 2010;17:127–38. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Semiz M, Kavakci Ö, Pekşen H, Tunçay M, Özer Z, Aydinkal SemiZ E, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder, alexithymia and somatoform dissociation in patients with fibromyalgia. Turkiye fiziksel tip ve rehabilitasyon dergisi-turkish journal of physical medicine and rehabilitation; 2014; 60: 3–11.

- 54.Charkhandeh M, Talib MA, Hunt CJ. The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy and an alternative medicine approach in reducing symptoms of depression in adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2016;239:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baldwin AL, Vitale A, Brownell E, Kryak E, Rand W. Effects of Reiki on pain, anxiety, and blood pressure in patients undergoing knee replacement: a pilot study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2017;31:80–9. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cassidy N, Collins K, Cyr D, Magni K. The Effect of Reiki on Women’s preoperative anxiety in an ambulatory surgery Center. J PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 2010;25:196. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2010.04.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials can be accessed by contacting the first author.