Abstract

Elevated arousal in anxiety is thought to affect attention control. To test this, we designed a visual short-term memory (VSTM) task to examine distractor suppression during periods of threat and no-threat. We hypothesized that threat would impair performance when subjects had to filter out large numbers of distractors. The VSTM task required subjects to attend to one array of squares while ignoring a separate array. The number of target and distractor squares varied systematically, with high (four squares) and low (two squares) target and distractor conditions. This study comprised two separate experiments. Experiment 1 used startle responses and white noise as to directly measure threat-induced anxiety. Experiment 2 used BOLD to measure brain responses. For Experiment 1, subjects showed significantly larger startle responses during threat compared to safe period, supporting the validity of the threat manipulation. For Experiment 2, we found that accuracy was affected by threat, such that the distractor load negatively impacted accuracy only in the threat condition. We also found threat-related differences in parietal cortex activity. Overall, these findings suggest that threat affects distractor susceptibility, impairing filtering of distracting information. This effect is possibly mediated by hyperarousal of parietal cortex during threat.

Keywords: visual short-term memory, threat, attention, orienting, anxiety, startle

Introduction

Anxiety is the most commonly diagnosed class of mental health disorders among Americans (Kessler et al., 2005; Delpino et al., 2022). Notably, anxiety significantly impairs individuals’ cognitive functioning and attentional abilities (Eysenck et al., 2007). Impaired attention control and elevated arousal are key symptoms that cut across anxiety disorders (Eysenck et al., 2007; Basanovic et al., 2023), but the degree to which these symptoms reflect common underlying mechanism is poorly understood.

One approach to studying the effects of arousal on attention control is to manipulate arousal during threat of unpredictable (electric) shock (Grillon and Ameli, 1998; Böcker et al., 2004). In this paradigm, subjects complete a cognitive task during periods of either safety or unpredictable shock threat. During the threat periods, participants know that the shock may come but the timing and frequency of the shocks are unpredictable. Changes in arousal are typically measured by quantifying the magnitude of the acoustic startle reflex (Lang et al., 1990; Grillon and Ameli, 1998), elicited by a loud white noise. Increases in arousal potentiate this response, thus yielding a direct physiological measure of arousal changes during this experimental arousal-induction paradigm (Braune et al., 1994; Hoehn et al., 1997; Grillon and Ameli, 1998; Parente et al., 2005). Additionally, this instructed threat paradigm requires very few cognitive resources, thus making it possible to complete concurrent cognitive tasks during the threat periods (Grillon, 2008; Schmitz and Grillon, 2012). These details make the unpredictable threat paradigm a robust and ecologically valid approach to studying anxiety as well as its interactions with cognition. For this reason, this paradigm is widely used and previously shown to induce state anxiety, affect task performance and alter patterns of functional neural connectivity (Lavric et al., 2003; Hansen et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2011, 2012; Clarke and Johnstone, 2013; Dunning et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2013a,b; McMenamin et al., 2014; Vytal et al., 2014; McMenamin and Pessoa, 2015; Balderston et al., 2017e).

Previous research into the mechanisms mediating the threat-related increases in arousal have implicated both cortical and subcortical regions like the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), insula, thalamus and parietal cortex (Davis et al., 2010; Balderston et al., 2017a). Critically, work from our group has previously shown that regions of the parietal cortex exhibit both hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity during threat periods compared to safe periods (Balderston et al., 2017a; Brown et al., 2023). It is well known that the parietal regions are critical for both endogenous and exogenous shifts of attention, suggesting that the effects of anxiety on attention control may be critically mediated by parietal cortex involvement (Rusconi et al., 2007; Capotosto et al., 2012; Frank and Sabatinelli, 2012; Parisi et al., 2020). For example, the intraparietal sulcus is a region that is highly interconnected with the visual cortex, and known to be involved in attentional orienting (Rushworth, 1997; Molenberghs et al., 2007; Grimault et al., 2009). Accordingly, anxiety-related hyperactivity of this region may increase orienting responses to external stimuli, resulting in an increase in vigilance to environmental stimuli (Rushworth, 1997; Molenberghs et al., 2007). While adaptive evolutionarily, excessive vigilance can increase distraction susceptibility and interfere with attention control (Buodo et al., 2007).

To test the effects of arousal on attention control, we designed a visual short-term memory (VSTM) task, where subjects were instructed to simultaneously encode (targets) and filter out (distractors) shapes in a visual array. Critically, the number of targets and distractors could be independently manipulated on each trial, allowing us to independently assess visual short-term memory encoding and distractor suppression across trials. Previous work using this task to explore memory capacity has shown that accuracy decreases as combined set size increases, suggesting that accuracy may decrease at higher loads (Vogel and Machizawa, 2004). Additionally, subjects performed this task during safe and (unpredictable) threat blocks, allowing us to assess the effect of arousal on each of these manipulations (target encoding, distractor suppression). Given previous work showing that threat can decrease both accuracy (Vytal et al., 2012) and reaction time (Balderston et al., 2016), we hypothesized that threat would exacerbate the effects of target and/or distractor load on accuracy, while decreasing overall reaction times. In this study, we validated this task in a laboratory session where arousal was measured with the acoustic startle reflex (Experiment 1). We then had subjects complete the task in the MRI scanner while we recorded BOLD activity. Given that anxiety is known to impair attention control, including the ability to ignore irrelevant information (Rapee, 1991; Ansari et al., 2008; Price et al., 2011; White et al., 2011), we hypothesized that anxiety-related attention control deficits might manifest as difficulties in selectively filtering out distractors during the threat condition. Based on literature suggesting that contralateral delay activity is associated with distractor suppression (Vogel and Machizawa, 2004; Stout et al., 2013), we hypothesized that we would see increased parietal activity contralateral to the focus of attention during threat.

Materials and methods

Participants

Experiment 1

Sixteen healthy volunteers from the Washington DC area were recruited for this experiment. One participant withdrew, leaving 15 participants who completed the session [7 female; M (SD): 29.47 (7.52) years]. Note that recruitment was halted after 16 subjects after a preliminary analysis of the data showed a tendency for the startle probes to interfere with performance.

Experiment 2

Thirty-five healthy volunteers from the Washington DC area were recruited for this experiment. Four participants were excluded due to scheduling issues, and four participants were excluded due to scanner issues, leaving 27 participants who completed the session [13 female, M (SD): 30.33 (9.06) years].

In both studies, participants were excluded if they had current or history of any axis I psychiatric disorder as assessed by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Research Version, Non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP), family history of mania, schizophrenia, or other psychoses, current or history of any psychotropic or illicit drug use, contra-indications for fMRI, hearing loss or any other medical conditions that might interfere with the study. All participants gave written informed consent approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Combined Neuroscience Institutional Review Board and received financial compensation. See Supplementary Table S1 for additional Demographic information. All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

General Procedure

Experiment 1

Subjects arrived at the lab, completed the consent process, were briefed on the task, and were prepped for the procedure (Balderston et al., 2017c). The skin under the left eye was cleaned and prepped with an exfoliant gel, and afterward two electrodes were affixed directly below the left eye. Two additional electrodes were attached to the fingers of the right hand to measure skin conductance and serve as the ground for the EMG electrodes. Finally, two electrodes were attached to the left wrist to deliver the shock. Next the subject completed a shock workup procedure, which was used to calibrate the intensity of the shock. Afterward, they completed a white noise habituation run. Finally, they completed four runs of the VSTM task.

Experiment 2

The procedure for Experiment 2 was similar to Experiment 1, with the exception that subjects completed the task in the MRI scanner and did not receive white noise presentations. Subjects arrived at the lab, completed the consent process, were briefed on the task, and were prepped for the procedure. All metal was removed from the subjects’ person and the subject was given ear plugs for the scans. Two electrodes were attached to the left wrist to deliver the shock. Next the subject completed a shock workup procedure, which was used to calibrate the intensity of the shock. Finally, they completed four runs of the VSTM task.

Materials

VSTM task

On each trial, subjects were shown an arrow (150 ms) that pointed to either the left or right side of the screen (See Figure 1). Subjects were instructed to attend to the side of the screen corresponding to the arrow direction and ignore the contralateral side of the screen. After a delay (2000–5000 ms), subjects were then shown an array of squares (150 ms) and instructed to remember the squares on the target side and ignore the squares on the off-target side. After another delay (2000–5000 ms), subjects were shown a single target square ipsilateral to the arrow direction and instructed to indicate whether or not the square matched one of the previously presented target squares in color and position. Half of the trials were matches; half were mismatches. Similarly, half of the trials targeted the left half of the screen; half targeted the right. The number of target and distractor squares was systematically varied across trials to include orthogonal high (four squares) and low (two squares) target and distractor conditions. The timing of the events within each trial was jittered (see timing details above) and the timing of the intertrial interval was varied such that the duration of each trial was 13 s. There was a total of 4–8 min runs, each with 32 scored trials and 3 dummy (shock) trials. Trials took place during alternating periods of safety and threat. During the safe period, subjects were not at risk of receiving a shock. During the threat periods, subjects were at risk for receiving a shock at any point during the entire threat period. The subjects were instructed that the color of the circle at the center of the screen (where the fixation cross and directional cues were presented) indicated the type of block (safe vs threat). As in several of our previous studies, during safe periods this circle was blue, while during threat periods this circle was orange (Balderston et al., 2016, 2017b,e, 2020c). There were three shocks per run. During Experiment 1, white noise presentations were used to elicit startle responses during the retention intervals following square array presentations.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of task design. (A) Trials began with a cue (150 ms) period, where a centrally presented arrow pointed either to the left or right. Following a short delay, an array of target (ipsilateral to arrow direction) and distractor (contralateral to arrow description) squares were presented (150 ms). Following another delay, a single prompt square was presented (1000 ms). Subjects were instructed to indicate whether or not the prompt square matched one of the previous target squares. (B) The number of target and distractor squares was systematically varied across trials to include orthogonal high (four squares) and low (two squares) target and distractor conditions.

Acoustic startle stimulus (white noise)

A 40 ms burst of a 103 dB white noise (near instantaneous rise/fall times) was delivered via the computer soundcard using standard over-the-ear headphones. Prior to the task, subjects completed a habituation block with nine unsignaled presentations of the white noise.

Electromyography

Blink responses were measured using EMG recorded from the orbicularis oculi muscle with two tin cup electrodes placed under the left-eye. EMG was sampled at a rate of 2000 Hz using a Biopac data acquisition unit (MP150; Biopac Systems Inc., USA) with Acknowledge 4.4 software.

Shock

A 100 ms, 200 Hz stimulation train was used as the aversive shock. The shock was delivered to the left wrist via 11 mm disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes (EL508, Biopac Systems Inc., USA), using a constant current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer, LLC, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA). Shock intensity was set prior to the experiment using a workup procedure, where subjects received a series of shocks of increasing intensity until they rated the stimulation as ‘uncomfortable but not painful’. This intensity was used for the remainder of the experiment.

EMG processing

EMG responses from Experiment 1 were analyzed using the analyze startle packaged developed by Dr Balderston (https://github.com/balders2/analyze_startle), bandpass filtered (30–500 Hz), rectified and smoothed with a 20 ms time constant. Blinks were scored as the peak during the response period (20–120 ms after white noise) minus the mean EMG signal during the baseline period (50 ms prior to white noise). Trials where no blink was detected (i.e. peak—mean was less than the range of the baseline) were scored as a 0. Trials where excessive noise was detected during the baseline (i.e. SD was greater than 2× the SD of the entire run) were scored as missing data (Balderston et al., 2017c, d, 2020a, 2020b; Teferi et al., 2022). Blinks were then converted to t-scores ((X− MX)/SDX × 10 + 50) to reduce large inter-individual differences in blink magnitude (Blumenthal et al., 2005).

Scans

Scans were collected on a Siemens 3 T Skyra MRI scanner with a 32-channel head coil. Subjects viewed the stimuli via a coil mounted mirror system. We acquired a T1-weighted MPRAGE (TR = 2530 ms; TE1 = 1.69 ms; TE2 = 3.55 ms; TE3 = 5.41 ms; TE4 = 7.27 ms; flip angle = 7°) with 176, 1 mm axial slices [matrix = 256 mm × 256 mm; field of view (FOV) = 204.8 mm × 204.8 mm]. For functional data, we acquired whole-brain multi-echo echoplanar images (EPI; TR = 2000 ms; TEs = 13.8, 31.2, 48.6 ms; flip angle = 70°) with 32, 3 mm axial slices (matrix = 64 mm × 64 mm; FOV = 192 mm × 192 mm) aligned to the ac-PC line. We also acquired a reverse phase-encoded ‘blip’ EPI image to correct for EPI distortion in the phase encoding direction.

fMRI pre-processing

Data were processed using afni_proc.py (Kundu et al., 2012), which included slice-timing correction, despiking, volume registration, identification of non-BOLD components using a TE-dependent independent components analysis (ICA) (Kundu et al., 2012), scaling, EPI distortion correction, nonlinear normalization to the MNI template, and blurring with a 6 mm FWHM gaussian kernel. fMRI timeseries were scrubbed for motion (threshold set at > 0.5 mm RMS), and modeled using a first-level GLM. This GLM included regressors of no interest including: baseline (polynomial estimates), six motion parameters (x, y, z, roll, pitch, yaw) and their derivatives, the non-BOLD component timeseries, shock onsets, button presses, and response prompt. The GLM also included regressors of interest corresponding to the cue and array presentations of the VSTM task.

Statistical analysis

Startle

Startle data were processed and converted to t-scores. These scores were then analyzed using a paired sample t-test contrasting responses during safe and threat blocks.

Performance

Percent correct and average reaction time was calculated for each individual and each condition. No response trials were counted as missing data for reaction time scores, since no reaction time could be recorded. For accuracy, no response trials were recorded as incorrect, such that the accuracy scores would reflect the percentage of correct responses. Accuracy and reaction time scores were analyzed using a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs high) repeated measures ANOVA. Interaction effects were characterized by paired sample t-tests where appropriate. Partial eta-squared and Cohen’s d were calculated for ANOVA effects and t-tests, respectively.

fMRI analysis

The resulting beta maps from the first level GLM were then analyzed using a whole-brain voxelwise analyses. We extracted the betas from the first-level GLM corresponding to the cue and the array and performed mixed-model ANOVAs on the values for each event type. For the cue events, we used a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (cue direction: left vs right hemisphere) ANOVA. For the array events, we used a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (cue direction: left vs right hemisphere) × 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs high) repeated measures ANOVA. Note that the analysis of the fMRI data differed from the analysis of the behavioral data in two primary ways First, for the fMRI data, we examined two within-trial events, the cue event (directional arrow to direct attentional focus) and the array event (array of target/distractor shapes to be encoded/suppressed). For the cue period, the analysis differed from the behavioral analysis because the cue was presented before the array, which defined the target and distractor load manipulations. Accordingly, these factors were not included in the analysis of the cue-related activity. Second, for both periods cue direction was added to the model. While likely not critical for the behavioral data, cue direction was important for examining both cue-related and array-related activity because the visual and attentional networks are retinotopically organized, with the left hemisphere primarily responding to the right hemifield and the right hemisphere primarily responding to the left hemifield.

We used cluster-based thresholding to correct for multiple comparisons by conducting 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations (Forman et al., 1995). We used a two-tailed voxelwise P-value of 0.001, and a non-Gaussian autocorrelation function that better approximates BOLD data based on the smoothness of the residuals from the first-level timeseries regressions (Cox et al., 2017), and clustered voxels with adjoining faces and edges. The result was a minimum cluster size of 55, 3 mm isotropic voxels, which was used for all analyses.

Results

Experiment 1

Startle

As a manipulation check, we examined the effect of threat on startle responses. As designed, subjects showed significantly larger startle responses during threat (Figure 2; threat: M = 51.79; SD = 2.44) compared to safe periods [safe: M = 48.41; SD = 2.05; t(14) = 2.82; P = 0.014; d = 0.73].

Fig. 2.

Startle responses during Experiment 1. Raw startle responses were converted to t-scores (X − MX)/SDX ×10 + 50). Bars represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Accuracy

To determine the effect of threat on VSTM performance, we performed a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs high) repeated measures ANOVA on accuracy scores (Table 1 and Figure 3). We found a significant main effect of target load [f(1,14) = 20.61; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.6], suggesting that subjects were more accurate on low load compared to high load trials. We found no other significant main effects or interactions (all P’s > 0.1; See Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Accuracy and reaction time for Experiments 1 and 2

| Target | High | Low | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distractor | High | Low | High | Low |

| Experiment 1 | ||||

| Accuracy | ||||

| Safe | 66.97 (18.25) | 72.47 (14.49) | 79.90 (15.13) | 78.84 (15.55) |

| Threat | 69.89 (12.10) | 67.08 (18.63) | 79.83 (14.22) | 81.45 (12.07) |

| RT | ||||

| Safe | 1119.33 (377.48) | 1128.20 (420.48) | 987.01 (289.52) | 979.79 (347.62) |

| Threat | 1143.34 (378.39) | 1082.03 (346.23) | 962.71 (322.61) | 969.66 (341.60) |

| Experiment 2 | ||||

| Accuracy | ||||

| Safe | 60.18 (17.77) | 59.08 (18.86) | 73.51 (23.94) | 73.08 (20.56) |

| Threat | 63.28 (18.07) | 69.05 (16.48) | 72.01 (21.38) | 77.58 (24.11) |

| RT | ||||

| Safe | 1208.09 (315.01) | 1108.87 (254.65) | 1184.58 (315.49) | 1101.02 (266.37) |

| Threat | 1247.66 (313.85) | 1238.28 (281.88) | 1041.70 (215.04) | 1096.09 (278.37) |

Fig. 3.

Accuracy and reaction time during Experiment 1. (A) Percent correct during the safe periods of the VSTM task. (B) Percent correct during the threat periods of the VSTM task. (C) Reaction time during the safe periods of the VSTM task. (D) Reaction time during the threat periods of the VSTM task. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Reaction time

Like accuracy scores we performed a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs high) repeated measures ANOVA on reaction time (Table 1 and Figure 3). Like accuracy, we found a significant main effect of target load [f(1,14) = 19.54; P = 0.001; eta-squared = 0.58], suggesting that subjects were faster on the low compared to high load trials. In addition, we found a significant three-way interaction condition by target load by distractor load interaction [f(1,14) = 6.92; P = 0.02; eta-squared = 0.33; all other P’s > 0.1]. However, when we analyzed the safe and threat trials separately with 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs high) repeated measures ANOVAs, we found no differential effects for safe trials compared to threat trials (all P’s > 0.1; See Supplementary Table S2). The only effects observed were significant main effects for target load for both the safe [f(1,14) = 10.61; P = 0.006; eta-squared = 0.43] and threat [f(1,14) = 22.21; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.61] trials, consistent with the main effect from the 2×2×2 ANOVA.

Experiment 2

Accuracy

As with Experiment 1, we performed a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs. high) repeated measures ANOVA on accuracy scores (Table 1 and Figure 4). We found a significant two-way interaction of condition by distractor interaction [f(1,26) = 5.72; P = 0.024; eta-squared = 0.18], which also likely contributed to a trend toward a main effect for distractor load [f(1,26) = 3.56; P = 0.071; eta-squared = 0.12]. To characterize the interaction, we analyzed accuracy for safe and threat trials separately and found distinct patterns for both. For safe trials, we found a significant main effect for target load [f(1,26) = 38.22; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.6], but no main effect for distractor load [f(1,26) = 0.16; P = 0.691; eta-squared = 0.01] and no target load by distractor load interaction [f(1,26) = 0.03; P = 0.856; eta-squared = 0]. For threat trials, we found significant main effects for both target load [f(1,26) = 10.41; P = 0.003; eta-squared = 0.29] and distractor load [f(1,26) = 9.58; P = 0.005; eta-squared = 0.27], but no target load by distractor load interaction [f(1,26) = 0; P = 0.957; eta-squared = 0]. We also found two significant main effects, for condition [f(1,26) = 10.61; P = 0.003; eta-squared = 0.29] and for target load [f(1,26) = 33.18; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.56; all other P’s < 0.1; See Supplementary Table S3].

Fig. 4.

Accuracy and reaction time during Experiment 2. (A) Percent correct during the safe periods of the VSTM task. (B) Percent correct during the threat periods of the VSTM task. (C) Reaction time during the safe periods of the VSTM task. (D) Reaction time during the threat periods of the VSTM task. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Reaction time

As with Experiment 1, we performed a 2 (condition: safe vs threat) × 2 (target load: low vs high) × 2 (distractor load: low vs high) repeated measures ANOVA on reaction time (Table 1 and Figure 4). We found significant condition by target load [f(1,26) = 19.77; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.43] and condition by distractor load interactions [f(1,26) = 14.09; P = 0.001; eta-squared = 0.35; all other P’s > 0.1; see Supplementary Table S3]. To characterize these interactions, we analyzed safe and threat trials separately. As with accuracy, we found distinct patterns for the safe and threat trials. For safe trials, we found a significant main effect of distractor load [f(1,26) = 12.84; P = 0.001; eta-squared = 0.33], but no main effect for target load [f(1,26) = 0.35; P = 0.56; eta-squared = 0.01] and no condition by target load interaction [f(1,26) = 0.07; P = 0.798; eta-squared = 0]. In contrast, for threat trials we found a significant main effect for target load [f(1,26) = 66.43; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.72], but no main effect for distractor load [f(1,26) = 1.83; P = 0.187; eta-squared = 0.07] and no condition by target load interaction [f(1,26) = 1.29; P = 0.266; eta-squared = 0.05]. We also found significant main effects for both target load [f(1,26) = 34.11; P < 0.001; eta-squared = 0.57] and distractor load [f(1,26) = 5.09; P = 0.033; eta-squared = 0.16]; however, given that the effect for target load was only significant during the threat periods and the effect for distractor load was only significant during the safe periods, it is likely that these main effects were driven by the above interactions.

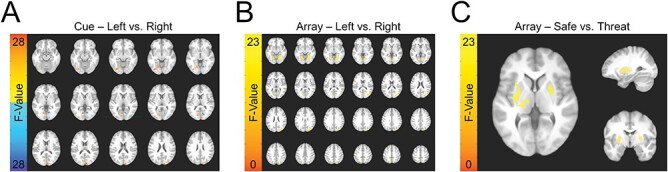

fMRI results

For both the cue and the array presentations, visual evoked activity differentiated trials where subjects were instructed to fixate on the left vs the right hemisphere, which indicated a distinct neural response based on the direction of attention (Figure 5). For the cue presentations, this activity was greatest in the hemisphere contralateral to the focus of attention, which replicated previous findings showing that top-down attentional instructions can bias visual processing (Table 2). Additionally, for the array presentations, we saw bilateral threat-related activity in a pair of clusters that included voxels in both the striatum and the insula, which has also been previously shown to be responsive to threat (Table 3). Finally, in parietal cortex, we saw a threat by attentional focus interaction (Figure 6). During the safe period, we saw greater activity when attention was focused on the left hemisphere [left = 0.051 (0.089); right = −0.016 (0.069); t(26) = −3.47; P = 0.002; d = −0.68]. In contrast, during the threat period, we saw greater activity when attention was focused toward the right visual field [left = −0.023 (0.107); right = 0.029 (0.079); t(26) = 2.51; P = 0.018; d = 0.49]. No other significant main effects or interactions were detected.

Fig. 5.

BOLD responses evoked by the directional cue and square array during the VSTM task. (A) The effect of cue direction on BOLD activity evoked by the cue. (B) The effect of cue direction on BOLD activity evoked by the square array. (C) The effect of threat on BOLD activity evoked by the square array.

Table 2.

Whole-brain results for cue-evoked activity

| MNI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Voxels | x | y | z | Max F | Effect |

| Hemisphere | ||||||

| Left lingual gyrus | 109 | 4.5 | 70.5 | 4.5 | 33.18 | L > R |

| Right superior occipital gyrus | 71 | −13.5 | 97.5 | 22.5 | 37.16 | L > R |

| Left fusiform gyrus | 67 | 34.5 | 79.5 | −10.5 | 31.34 | L > R |

| Right calcarine gyrus | 67 | −13.5 | 73.5 | 10.5 | 25.63 | R > L |

| Condition × Hemisphere | ||||||

| Bilateral parietal cortex | 274 | 25.5 | 34.5 | 67.5 | 30.6 | *** |

Table 3.

Whole-brain results for array-evoked activity

| MNI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Voxels | x | y | z | Max F | Effect |

| Hemisphere | ||||||

| Right fusiform gyrus | 274 | −25.5 | 52.5 | −7.5 | 40.37 | R > L |

| Right superior occipital gyrus | 226 | −28.5 | 85.5 | 34.5 | 33.06 | L > R |

| Left lingual gyrus | 209 | 13.5 | 67.5 | −4.5 | 44.14 | L > R |

| Left precuneus | 69 | 7.5 | 61.5 | 49.5 | 27.26 | L > R |

| Condition | ||||||

| Left putamen | 113 | 10.5 | 22.5 | −4.5 | 30.19 | T > S |

| Right putamen | 75 | −37.5 | −4.5 | 16.5 | 32.24 | T > S |

| Left superior occipital gyrus | 62 | 16.5 | 88.5 | 25.5 | 21.64 | T > S |

| Left insula lobe | 55 | 34.5 | 28.5 | 22.5 | 24.02 | T > S |

Fig. 6.

Parietal cortex BOLD responses evoked by the square array during the VSTM task. Left panel: Voxelwise effects driven by the threat by laterality interaction. Right panel: Bar graph representing differential effects of attentional focus (left vs right) and threat on BOLD activity in the cluster shown in the left panel. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of threat of shock on attentional control and distractor suppression during a VSMT. Our research aimed to explore the interaction between anxiety-related arousal and attentional processes, building on previous findings related to anxiety and its effects on cognitive functioning. The findings offer some support to support our initial hypothesis, that heightened anxiety-related arousal impairs visual short-term memory performance when there are more distractors. In the safe conditions of our study, the presence of distractors slowed participants’ reaction times without compromising their accuracy, potentially indicating a typical pattern of attentional interference (Gao et al., 2011; Bettencourt and Xu, 2016). However, intriguingly, under the threat condition, there seemed to be no significant impact on reaction time, suggesting that heightened arousal may not have influenced the speed of processing information. Instead, the threat condition significantly affected accuracy, potentially indicating that participants’ ability to filter out distractors and maintain precision in their responses may have been compromised (Stout et al., 2013). These findings suggest that threat-induced arousal may affect distractor susceptibility, potentially disrupting the cognitive processes responsible for selective attention. Furthermore, we suggest that the instructed threat blocks could have biased subjects toward more automatic (and less) accurate response patterns. Consistent with conclusion, previous literature suggests that heightened arousal may impair the cognitive mechanisms responsible for focusing attention and ignoring irrelevant stimuli (Rapee, 1991; Ansari et al., 2008). Our neuroimaging data revealed distinct patterns of activity in the parietal cortex across threat conditions: during safe conditions, increased activity was observed on trials where attention was directed to the left hemifield, while under threat conditions, increased activity was observed on trials where attention was directed to the right hemifield. This interaction between threat conditions and attentional focus in the parietal cortex could offer insight into how threat potentially affects distractor susceptibility, but more evidence is needed to suggest that the parietal cortex perhaps plays a central role in mediating this effect. These results potentially underscore the intricate relationship between anxiety-induced arousal, attentional control, and the underlying neural mechanisms, shedding some light on the complex interplay between cognitive processes and emotional states (Robinson et al., 2013b).

Participants engaged in effortful attentional processes during the safe trials to effectively filter out distractors, perhaps indicating a deliberate and controlled mechanism of attention. However, under the threat condition, a shift seemed to occur in their attentional strategy. Participants seemed to rely on automatic processes, as reflected in the lack of significant changes in reaction time. Paradoxically, this automatic mode of attentional processing during threat led to a notable decrease in accuracy, possibly suggesting that the filtering process was impaired under heightened arousal. This proposed shift in attentional mechanisms appeared to involve a lateralization effect: effortful attentional processes might have driven attention toward the left hemisphere, while automatic attentional processes seemed to predominantly activate the right hemisphere. While the current results do not offer convincing evidence to support this interpretation, they do raise this possibility as a testable hypothesis, and future experiments could investigate the neural underpinnings of this attentional switch, potentially exploring the involvement of specific regions within the parietal cortex and their connectivity patterns. This study’s results are consistent with previous research, providing emerging insights into the complex interplay between attention, arousal, and hemispheric specialization, potentially laying the foundation for further explorations in the field of cognitive neuroscience (White et al., 2023).

These findings hold relevance in the context of anxiety, possibly shedding light on how heightened anxiety may impact the ability to filter out distractors and respond to threats effectively. The results suggest that anxiety might disrupt the balance between deliberate attentional control and automatic, stimulus-driven processes (Hasher and Zacks, 1979; Corbetta and Shulman, 2002; Teachman et al., 2012). Under threat, automatic distractor suppression seems to be bolstered, indicating a heightened vigilance towards potentially threatening stimuli. However, this increased vigilance comes at a cost, and the accuracy of responses could suffer. In the face of anxiety, individuals may find themselves more prone to automatic, reflexive responses (Beck and Clark, 1997), prioritizing the rapid identification and suppression of potential threats over the careful, effortful evaluation of task-related information. This shift in attentional dynamics not only highlights the intricacies of anxiety-related attention deficits but also underscores the multifaceted challenges faced by individuals experiencing heightened anxiety. Understanding these processes is crucial, not only for advancing our knowledge of the neural mechanisms underlying anxiety but also for developing targeted interventions that can help individuals regulate their attentional responses in anxiety-provoking situations, ultimately improving their cognitive functioning and overall well-being.

The significant increase in participants’ startle responses under threat conditions serves as an indicator of the successful induction of anxiety, validating the experiment’s ability to create an anxious state (Davis et al., 2010). Moreover, our study tests attentional control by examining the differential activation patterns in the visual cortex during the cue and square array presentation phases. Threat activated key brain regions associated with emotional processing, such as the insula and thalamus, emphasizing the emotional intensity of the induced anxiety. Interestingly, the striatum, a region associated with both motivation and anxiety, also featured prominently in our findings (Cardinal et al., 2002; Lago et al., 2017). While the exact role of the striatum in this context warrants further exploration, its involvement suggests a potential link between anxiety-induced arousal and motor responses, hinting at the complex interconnections within the brain’s neural circuitry (Cardinal et al., 2002; Li et al., 2011). This analysis provides potential insights into the dynamic shifts in attentional focus and highlights the intricate neural processes involved in selective attention under varying emotional states. The experiment’s validity is further reinforced by the design, allowing for the exploration of the underlying neural mechanisms governing attentional regulation. By systematically manipulating the threat level and number of target or distractor squares, our study helps to understand the intricate interplay between anxiety, attentional control and threat processing.

Strengths and limitations

Our study’s strengths lie in the within-subject anxiety manipulation, enhancing result reliability. Fear induction through the threat of shock adheres to established practices, providing a robust anxiety-inducing method. Utilizing diverse measurements, including behavior, physiology (startle responses) and neuroimaging (fMRI), ensures a comprehensive understanding of anxiety’s impact on attention. The dual-experiment design and transparent open science practices enhance internal validity and contribute clinically relevant insights for anxiety disorders.

Interpreting our findings is contingent upon acknowledging several limitations. The relatively small sample size may constrain the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, our study exclusively examined the immediate effects of anxiety-induced arousal, offering insights into immediate responses but overlooking the enduring, chronic nature of attentional deficits in anxiety-related disorders. The absence of a sham or control condition in our experimental design poses a significant limitation, as it complicates distinguishing the effects attributed to the threat of shock from those influenced by potential confounding variables. Incorporating a sham or control condition in future studies would bolster the research’s rigor, providing a more robust basis for evaluating the impact of arousal-induced anxiety on attentional processes.

Conclusions

In summary, this investigation illuminates the intricate dynamics between heightened anxiety, attentional control and cognitive functions. Our findings suggest a shift from effortful to automatic attentional processes under threat, manifested by sustained reaction times but diminished accuracy. The observed lateralization effect in the parietal cortex underscores the nuanced interplay between hemispheric specialization and anxiety’s impact on attention. Looking ahead, this study prompts further exploration with an emphasis on larger, more diverse samples, specific brain region investigations, and the inclusion of control conditions. These future endeavors are pivotal for refining our comprehension of anxiety-related attentional mechanisms. This research not only deepens our understanding of anxiety’s influence on attention but also lays the groundwork for nuanced explorations of cognitive processes within emotional contexts, offering potential avenues for targeted interventions and enhanced neural models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study team would like to thank the following individuals who contributed to Dr. Balderston’s K01 project: Dr Kerry Ressler, Dr Michael Thase and Dr Kristin Linn. The study team would also like to thank the DSMB members who oversaw the project: Dr Lindsay Oberman (Chair), Dr Alex Shackman and Dr Gang Chen. This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the CUBIC computing cluster at the University of Pennsylvania. (https://www.med.upenn.edu/cbica/cubic.html). The authors would like to thank Maria Prociuk for her expertise and assistance in submitting the paper. We would also like to thank the participants for their time and effort.

Contributor Information

Abigail Casalvera, Center for Neuromodulation in Depression and Stress, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Madeline Goodwin, Section on the Neurobiology of Fear and Anxiety, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Kevin G Lynch, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Marta Teferi, Center for Neuromodulation in Depression and Stress, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Milan Patel, Center for Neuromodulation in Depression and Stress, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Christian Grillon, Section on the Neurobiology of Fear and Anxiety, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Monique Ernst, Section on the Neurobiology of Fear and Anxiety, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Nicholas L Balderston, Center for Neuromodulation in Depression and Stress, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Author contributions

CRediT author statement according to: https://www.elsevier.com/authors/policies-and-guidelines/credit-author-statement.

Conceptualization: Christian Grillon (Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition), Monique Ernst (Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision), Nicholas L. Balderston (Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition), Kevin G. Lynch (Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing), Madeline Goodwin (Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing), Abigail Casalvera (Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization), Marta Teferi (Writing – Review & Editing), Milan Patel (Writing – Review & Editing).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at SCAN online.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they had no conflict of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH – National Institutes of Health (NIH Grant ZIAMH002798; www.ClinicalTrial.gov identifier: NCT00047853: Protocol ID 02-M-0321). This project was also supported in part by two NARSAD Young Investigator Grants from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (NLB: 2018, 2021); and by a K01 award K01MH121777 (NLB).

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- Ansari T.L., Derakshan N., Richards A. (2008). Effects of anxiety on task switching: evidence from the mixed antisaccade task. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Beydler E.M., Goodwin M., et al. (2020a). Low-frequency parietal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces fear and anxiety. Translational Psychiatry, 10, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Beydler E.M.E.M., Roberts C., et al. (2020b). Mechanistic link between right prefrontal cortical activity and anxious arousal revealed using transcranial magnetic stimulation in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45, 694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Flook E., Hsiung A., et al. (2020c). Anxiety patients rely on bilateral DLPFC activation during verbal working memory. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience 15, 1288–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Hale E., Hsiung A., et al. (2017a). Threat of shock increases excitability and connectivity of the intraparietal sulcus. eLife, 6, e23608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Hsiung A., Ernst M., et al. (2017b). Effect of threat on right dlPFC activity during behavioral pattern separation. Journal of Neuroscience, 37, 9160–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Hsiung A., Liu J., et al. (2017c). Reducing state anxiety using working memory maintenance. Journal of Visualized Experiments, e55727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Liu J., Roberson-Nay R., et al. (2017d). The relationship between dlPFC activity during unpredictable threat and CO2-induced panic symptoms. Translational Psychiatry, 7, 1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Mathur A., Adu-Brimpong J., et al. (2017e). Effect of anxiety on behavioural pattern separation in humans. Cognition and Emotion, 31, 238–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderston N.L., Quispe-Escudero D., Hale E., et al. (2016). Working memory maintenance is sufficient to reduce state anxiety. Psychophysiology, 53, 1660–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanovic J., Todd J., van Bockstaele B., et al. (2023). Assessing anxiety-linked impairment in attentional control without eye-tracking: the masked-target antisaccade task. Behavior Research Methods, 55, 135–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Clark D.A. (1997). An information processing model of anxiety: automatic and strategic processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt K.C., Xu Y. (2016). Decoding the content of visual short-term memory under distraction in occipital and parietal areas. Nature Neuroscience, 19, 150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal T.D., Cuthbert B.N., Filion D.L., et al. (2005). Committee report: guidelines for human startle eyeblink electromyographic studies. Psychophysiology, 42, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böcker K.B.E., Baas J.M.P., Kenemans J.L., et al. (2004). Differences in startle modulation during instructed threat and selective attention. Biological Psychology, 67, 343–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braune S., Albus M., Fröhler M., et al. (1994). Psychophysiological and biochemical changes in patients with panic attacks in a defined situational arousal. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 244, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L., White L.K., Makhoul W., et al. (2023). Role of the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) in anxiety and cognition: opportunities for intervention for anxiety-related disorders. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 23, 100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buodo G., Peyk P., Junghöfer M., et al. (2007). Electromagnetic indication of hypervigilant responses to emotional stimuli in blood-injection-injury fear. Neuroscience Letters, 424, 100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capotosto P., Corbetta M., Romani G.L., et al. (2012). Electrophysiological correlates of stimulus-driven reorienting deficits after interference with right parietal cortex during a spatial attention task: A TMS-EEG study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24, 2363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal R.N., Parkinson J.A., Hall J., et al. (2002). Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 26, 321–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R., Johnstone T. (2013). Prefrontal inhibition of threat processing reduces working memory interference. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M., Shulman G.L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews, Neuroscience, 3, 215–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R.W., Chen G., Glen D.R., et al. (2017). FMRI Clustering in AFNI: False-Positive Rates Redux. Brain Connectivity, 7, 152–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Walker D.L., Miles L., et al. (2010). Phasic vs sustained fear in rats and humans: role of the extended amygdala in fear vs anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 105–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpino F.M., da Silva C.N., Jerônimo J.S., et al. (2022). Prevalence of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 2 million people. Journal of Affective Disorders, 318, 272–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning J.P., DelDonno S., Hajcak G. (2013). The effects of contextual threat and anxiety on affective startle modulation. Biological Psychology, 94, 130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck M.W., Derakshan N., Santos R., et al. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7, 336–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S.D., Cohen J.D., Fitzgerald M., et al. (1995). Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): use of a cluster-size threshold. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 33, 636–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D.W., Sabatinelli D. (2012). Stimulus-driven reorienting in the ventral frontoparietal attention network: the role of emotional content. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Xu X., Chen Z., et al. (2011). Contralateral delay activity tracks object identity information in visual short term memory. Brain Research, 1406, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C. (2008). Models and mechanisms of anxiety: evidence from startle studies. Psychopharmacology, 199, 421–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C., Ameli R. (1998). Effects of threat of shock, shock electrode placement and darkness on startle. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 28, 223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimault S., Robitaille N., Grova C., et al. (2009). Oscillatory activity in parietal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during retention in visual short‐term memory: additive effects of spatial attention and memory load. Human Brain Mapping, 30, 3378–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A.L., Johnsen B.H., Thayer J.F. (2009). Relationship between heart rate variability and cognitive function during threat of shock. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 22, 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L., Zacks R.T. (1979). Automatic and effortful processes in memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108, 356–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn T., Braune S., Scheibe G., et al. (1997). Physiological, biochemical and subjective parameters in anxiety patients with panic disorder during stress exposure as compared with healthy controls. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 247, 264–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Chiu W.T., Demler O., et al. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu P., Inati S.J., Evans J.W., et al. (2012). Differentiating BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series using multi-echo EPI. NeuroImage, 60, 1759–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lago T., Davis A., Grillon C., et al. (2017). Striatum on the anxiety map: small detours into adolescence. Brain Research, 1654, 177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P.J., Bradley M.M., Cuthbert B.N. (1990). Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychological Review, 97, 377–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavric A., Rippon G., Gray J.R. (2003). No title found. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Schiller D., Schoenbaum G., et al. (2011). Differential roles of human striatum and amygdala in associative learning. Nature Neuroscience, 14, 1250–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin B.W., Langeslag S.J.E., Sirbu M., et al. (2014). Network organization unfolds over time during periods of anxious anticipation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 11261–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin B.W., Pessoa L. (2015). Discovering networks altered by potential threat (“anxiety”) using quadratic discriminant analysis. NeuroImage, 116, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs P., Mesulam M.M., Peeters R., et al. (2007). Remapping attentional priorities: Differential contribution of superior parietal lobule and intraparietal sulcus. Cerebral Cortex, 17, 2703–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente A.C.B.V., Garcia-Leal C., Del-Ben C.M., et al. (2005). Subjective and neurovegetative changes in healthy volunteers and panic patients performing simulated public speaking. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 15, 663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi G., Mazzi C., Colombari E., et al. (2020). Spatiotemporal dynamics of attentional orienting and reorienting revealed by fast optical imaging in occipital and parietal cortices. NeuroImage, 222, 117244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.B., Eldreth D.A., Mohlman J. (2011). Deficient prefrontal attentional control in late-life generalized anxiety disorder: an fMRI investigation. Translational Psychiatry, 1, e46–e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee R.M. (1991). Generalized anxiety disorder: a review of clinical features and theoretical concepts. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 419–40. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O.J., Charney D.R., Overstreet C., et al. (2012). The adaptive threat bias in anxiety: amygdala–dorsomedial prefrontal cortex coupling and aversive amplification. NeuroImage, 60, 523–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O.J., Krimsky M., Grillon C. (2013a). The impact of induced anxiety on response inhibition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O.J., Letkiewicz A.M., Overstreet C., et al. (2011). The effect of induced anxiety on cognition: threat of shock enhances aversive processing in healthy individuals. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 11, 217–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O.J., Vytal K., Cornwell B.R., et al. (2013b). The impact of anxiety upon cognition: perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi E., Turatto M., Umiltà C. (2007). Two orienting mechanisms in posterior parietal lobule: an rTMS study of the Simon and SNARC effects. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24, 373–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth M. (1997). The left parietal cortex and motor attention. Neuropsychologia, 35, 1261–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A., Grillon C. (2012). Assessing fear and anxiety in humans using the threat of predictable and unpredictable aversive events (the NPU-threat test). Nature Protocols, 7, 527–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout D.M., Shackman A.J., Larson C.L. (2013). Failure to filter: anxious individuals show inefficient gating of threat from working memory. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman B.A., Joormann J., Steinman S.A., et al. (2012). Automaticity in anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 575–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teferi M., Makhoul W., Deng Z.-D., et al. (2022). Continuous theta burst stimulation to the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may increase potentiated startle in healthy individuals. Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science, 3, 470–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E.K., Machizawa M.G. (2004). Neural activity predicts individual differences in visual working memory capacity. Nature, 428, 748–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vytal K.E., Cornwell B.R., Arkin N., et al. (2012). Describing the interplay between anxiety and cognition: from impaired performance under low cognitive load to reduced anxiety under high load. Psychophysiology, 49, 842–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vytal K.E., Overstreet C., Charney D.R., et al. (2014). Sustained anxiety increases amygdala–dorsomedial prefrontal coupling: a mechanism for maintaining an anxious state in healthy adults. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 39, 321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L.K., Makhoul W., Teferi M., et al. (2023). The role of dlPFC laterality in the expression and regulation of anxiety. Neuropharmacology, 224, 109355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L.K., McDermott J.M., Degnan K.A., et al. (2011). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: the moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 735–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.