Abstract

We generated recombinant viruses in which the kinetics of expression of the leaky-late VP5 mRNA was altered. We then analyzed the effect of such alterations on viral replication in cultured cells. The VP5 promoter and leader sequences from positions −36 to +20, containing the TATA box and an initiator element, were deleted and replaced with a strong early (dUTPase), an equal-strength leaky-late (VP16), or a strict-late (UL38) promoter. We found that recombinant viruses containing the dUTPase promoter inserted in the VP5 locus expressed VP5-encoding mRNA with early kinetics, while virus with the UL38 promoter inserted expressed such mRNA with strict-late kinetics. Further, in spite of differences in its functional architecture, the VP16 promoter fully substituted for the VP5 promoter. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the amounts of VP5 capsid protein produced by the recombinant viruses differed somewhat; however, on complementing C32 and noncomplementing Vero cells, such viruses replicated to titers equivalent to those of the rescued wild-type virus controls. Multistep virus growth in mouse embryo fibroblasts, rabbit skin cells, and Vero cells also demonstrated equivalent replication efficiencies for both recombinant and wild-type viruses. Further, recombinant viruses did not show any impairment in their ability to replicate on serum-starved or quiescent human lung fibroblasts. We conclude that the kinetics of the essential VP5 mRNA expression is not critical for viral replication in cultured cells.

Regulated gene expression during productive infection of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) has been extensively studied and reviewed (12, 14, 16, 18, 22, 23, 33, 36, 38). Three major classes of viral transcripts are expressed in a coordinated and sequential manner, providing proteins necessary for viral gene expression, replication, and viral assembly. The immediate-early or α transcripts, expressed in the absence of de novo protein synthesis, encode the major regulatory proteins of the virus (13, 24, 32, 36). These proteins are responsible for activating and regulating the expression of later classes of genes. A major fraction of the early or β transcripts encode proteins involved in viral DNA replication. As the level of genome replication approaches its maximum, expression of early transcripts declines and both the relative and absolute rates of late transcription increase. Late transcripts, many of which encode proteins involved in virus morphogenesis and maturation, have been divided into two subclasses: leaky-late (γ1) and strict-late (γ2). The former class of transcripts is expressed at appreciable levels prior to the initiation or in the absence of genome replication, and thus, expression of proteins encoded by them is not particularly sensitive to inhibitors of DNA replication (2, 21, 28, 34, 35).

This general pattern of regulated gene expression is typical of productive infection by the vast majority of DNA-containing viruses, but the actual mechanisms by which different viruses achieve this regulation differ. In the case of HSV, a major point of regulation is at the level of transcription, and we have demonstrated that both the kinetics and level of expression of a particular transcript are largely dictated by its promoter architecture (1, 6, 9, 25, 26, 29, 38).

A general tenant in modeling patterns of viral gene regulation is that the actual time and precise level of expression of a given transcript are of major importance in efficient productive infection and thus are tightly controlled. The complex pattern of regulation and the distinctive promoter structure utilized by HSV in mediating such regulation can be taken as presumptive evidence that this is, indeed, the case. A measure of the importance of the exact timing of the expression of specific viral genes should come from an assessment of the biological consequences of altering the parameters of their expression.

Desai et al. have demonstrated that a virus unable to express the gene encoding the major capsid protein, VP5 (UL19), does not form capsids and fails to process newly synthesized DNA into unit-length genomes (3, 20). We were interested in determining the consequences of altering this essential protein's kinetics of expression with regard to viral growth and pathogenesis. Accordingly, we have generated recombinant viruses in which a strong early (dUTPase), an equal-strength leaky-late (VP16), or a strict-late (UL38) promoter has been substituted for the VP5 promoter in the VP5 locus of the viral genome.

We utilized a complementing cell line expressing the VP5 capsid protein and a VP5-null virus generated by Desai et al. as a starting point (3, 20). As reported here, we have found that recombinant viruses containing the various promoter insertions express chimeric transcripts containing the cap and leader sequence of the inserted promoter and the coding sequence of the major capsid protein with the kinetics of the inserted promoter. Thus, the substituted promoters retain their normal kinetics of expression. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the amounts of VP5 capsid protein produced by the recombinant viruses differed somewhat and were roughly correlated with the levels of mRNA expression observed. Despite this, the recombinant viruses replicated to titers essentially equivalent to that seen with rescued wild-type (wt) virus controls on complementing (C32) and noncomplementing (Vero) cells. Multistep virus growth levels in mouse embryo fibroblasts, rabbit skin fibroblasts (RSF), and Vero cells were equivalent for recombinant and wt viruses. Further, recombinant viruses did not show any impairment in ability to replicate on serum-starved or quiescent human lung fibroblasts (HLF).

From this we conclude that the kinetics of expression of a required protein need not be tightly regulated for virus replication in a variety of cultured cells. We are currently investigating the effects of these viruses on pathogenesis in animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

RSF, Vero cells, and mouse embryo fibroblasts were maintained at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide in Eagle minimum essential medium containing 5% cadet calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. C32 cells, which complement VP5-null mutants (20), were a gift of P. Desai and S. Person. They were maintained under the conditions described above except that 10% fetal calf serum was used. Primary HLF (CCL-151) obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were maintained in Ham (F12K) medium with 15% fetal calf serum (FCS) in the absence of antibiotics.

Virus.

The VP5-null virus K5dZ was generated by partial deletion of the VP5 coding region and insertion of a lacZ gene as described in reference 3. This virus was used to generate recombinant viruses with promoter substitutions in the VP5 locus.

Generation of recombinant virus with the VP16, dUTPase, and UL38 promoters controlling expression of the VP5 (UL19) transcript.

The VP5 transcription start site occurs at base 40768 of the HSV strain 17syn+ (17). The BglII N fragment spanning bases 35734 through 41448 of the HSV-1 17syn+ genome, containing the VP5 promoter and coding region, was freshly subcloned from HSV 17syn+ DNA into the pGEM3 plasmid. An XbaI linker was added to replace the HpaI site at position −364 relative to the VP5 cap site. Digestion with XbaI and AgeI yielded a fragment containing the promoter from positions −364 to +268 in the VP5 translational reading frame. This was subcloned into the Psp72 vector (Promega). Deletion of the VP5 TATA and the Inr elements was done by standard methods of PCR-directed mutagenesis using appropriate primers. The mutated promoter, thus, contained a deletion from position −36 to position +20 relative to the cap site.

A DNA fragment containing the VP5 promoter sequence from position −364 to position −36 was generated by PCR using the upper-strand primer, containing an XbaI linker and sequences from positions −364 to −348, and the downstream primer, containing a NotI linker and sequences from positions −55 to −36. A second fragment, containing the sequences from positions +20 to +268, was generated by PCR using an upstream primer containing a ClaI linker with sequences from positions +20 to +43 and a lower-strand primer containing the AgeI restriction with sequences from positions +290 to +322. The PCR products were digested with the respective restriction enzymes and cloned into the Psp72 vector. The sequences of the fragments were confirmed before the next ligation step.

The VP16 promoter containing sequences from positions −272 to +6, the dUTPase promoter extending from −243 to +95, or the UL38 promoter with sequences from positions −97 to +87 was cloned into Bluescript KS(+) at the XbaI and HindIII sites. The same was done with a 300-bp bacterial chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) DNA “stuffer” fragment from EcoRI- and NcoI-digested plasmid C15dv17 (4, 5, 8). The Bluescript KS(+) vectors containing the VP16, dUTPase, UL38, or the CAT stuffer were digested with NotI and ClaI, and the resulting fragments were ligated along with the VP5 fragments containing the promoter region to obtain constructs with promoter insertions at the VP5 locus. These were cloned back into the BglII N fragment, the sequences were checked to ensure that no new mutation was introduced by PCR, and then the constructs were used to generate recombinant viruses.

Generation of recombinant viruses.

The BglII N plasmid constructs containing the substituted promoters were digested with BglII to release the fragment and cotransfected with infectious DNA isolated from the K5dZ virus (3, 27, 37) in the C32 complementing cell line along with 8 μl of the Lipofectin reagent (GIBCO-BRL). Recombinant viruses were isolated and screened on C32 cells, using a 32P-labeled PvuI fragment containing the VP5 coding region that was replaced by the β-galactosidase gene in the VP5-null virus (8, 19).

DNA from purified recombinant viruses was analyzed by PCR. This was done by using an upper-strand oligonucleotide that binds at positions −293 to −274 relative to the VP5 cap site (upstream of the insertion site) and an oligonucleotide that binds the lower strand in the VP5 leader region at positions +67 to +117 (downstream of the promoter insertion site). The PCR products of the wt VP5 promoter, VP16/VP5, dUTPase/VP5, and UL38/VP5 and of the CAT stuffer are 410, 688, 758, 594, and 710 bp, respectively. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and their identities were confirmed by Southern blotting with the 32P-labeled wt VP5, VP16, dUTPase, UL38, and CAT stuffer probes.

Asymmetrically PCR-amplified DNA from all recombinant viruses was directly sequenced by using the VP5 primer that binds in the VP5 leader region from positions +67 to +107 (7, 10). Independent isolates were generated by separate transfections to ensure that promoter activity was not influenced by second-site mutations.

RNA isolation and primer extension analysis.

RSF were infected with recombinant viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 PFU per cell. Infections were allowed to proceed for 2, 4, 6, or 8 h, and total RNA was isolated by using Trizol reagent (GIBCO-BRL) (11, 19). Primer extension analysis was carried out with 10 μg of total RNA and 10 fmol of 32P-labeled primers. A VP5 primer extending from 57 bases from the transcription start site in the VP5 leader was used to detect the chimeric transcripts. This primer gives rise to 63-, 142-, and 158-nucleotide (nt) bands for the substituted VP16, dUTPase, and UL38 promoters, respectively. Primers specific for VP16 wt, dUTPase wt, UL38 wt, and ICP27 transcripts were also used as internal controls. These produce products of 66, 143, 154, and 152 nt, respectively.

Multistep virus replication analysis.

RSF, Vero cells, and mouse embryo fibroblasts (105 cells each) were seeded on 6-well plates. The next day, they were infected with 100 (for RSF and Vero cells) or 10,000 (for mouse embryo fibroblasts) PFU per well. After adsorption at 37°C for 1 h, viruses were decanted and monolayers were overlaid with medium. Infectious viruses were harvested at 12 to 72 h postinfection. Cells and the culture medium were freeze-thawed three times, and virus titers were determined on Vero cells.

Primary HLF were allowed to become confluent, contact inhibited cells in medium containing 15% FCS, or they were serum starved for 7 days in medium containing 0.25% FCS. These cells were then infected with various recombinant viruses, individually, at an MOI of 0.05 PFU/cell. Infectious viruses were harvested at 12 and 24 h postinfection, and titers were determined on Vero cells (31).

Western blotting.

Individual RSF cultures (106 cells each) in 6-well plates were infected with virus at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell and harvested 24 h later. Proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–6% acrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose filters according to procedures described elsewhere (15, 20, 30). The filters were then blocked with 5% low-fat milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Then the filters were exposed to antibody to the VP5 protein. This antibody (NC-1), kindly provided by R. Eisenberg and G. Cohen, was used at a dilution of 1:10,000 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After five washes in PBS, the filters were incubated in PBS containing goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G and VP5 protein was detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL; Amersham).

RESULTS

Deletion of the VP5 promoter from the viral genome.

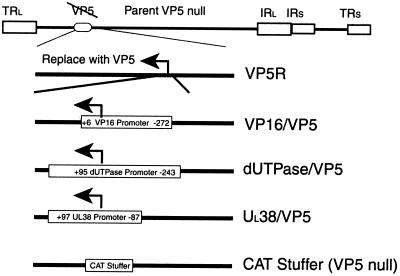

A schematic diagram outlining the replacement of the VP5 promoter is shown in Fig. 1. To ensure that the only modifications of the test virus were at the VP5 promoter, we generated a novel clone of the 5.7-kb BglII N fragment from wt 17syn+ DNA. This fragment, spanning 0.23 to 0.27 μm, extends 500 bp upstream of the VP5 transcript start site, through the complete translational reading frame. As described in Materials and Methods, we used PCR-directed mutagenesis to replace the VP5 TATA and the initiator elements from positions −36 to +20 with NotI and ClaI restriction sites. We then inserted the VP16 promoter (extending from positions −272 to +6), the dUTPase promoter (extending from positions −243 to +95), or the UL38 promoter (extending from positions −97 to +87) in place of the deleted VP5 TATA and initiator element in the VP5 locus.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of promoter substitutions in the VP5 locus. The BglII fragment N freshly cloned from wt HSV-1 (17syn+) was used to rescue the original VP5-null virus to generate the VP5 rescue construct (VP5R). This was used for all further constructions. The VP5 promoter and leader sequences from positions −36 to +20, containing the TATA box and an initiator element, were deleted and replaced with the VP16 (−272 to +6), dUTPase (−243 to +95), or UL38 (−97 to +87) promoter. A 300-bp bacterial CAT DNA fragment stuffer was inserted as a negative control. IRl, inverted long repeat; IRs, inverted short repeat; TRl, terminal long repeat.

Constructs were transfected along with infectious DNA from a VP5-null virus on the C32 complementing cell line to generate recombinant viruses containing the various promoters at the VP5 locus. As a positive control, the wt BglII N fragment was used to rescue the VP5-null virus. Further, a 300-bp DNA fragment derived from the bacterial CAT gene was inserted in place of the VP5 promoter as a negative control.

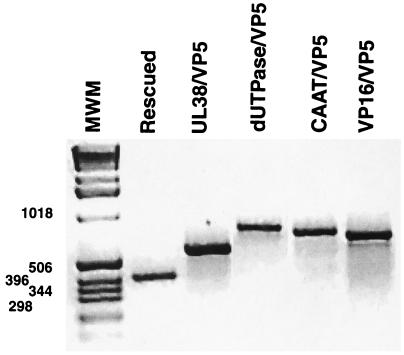

Recombinants were screened by hybridization and purified by three rounds of plaque purification on complementing C32 cells that express the wt VP5 gene from its cognate promoter (20). DNA from purified recombinant viruses was analyzed by PCR with an upper-strand oligonucleotide that binds at positions −293 to −274 relative to the VP5 cap site (upstream of the insertion site) and another oligonucleotide that binds the lower strand in the VP5 leader region at positions +67 to +117 (downstream of the promoter insertion site). The PCR products of the wt VP5 promoter, UL38/VP5, dUTPase/VP5, the CAT stuffer, and VP16/VP5, are 410, 594, 758, 710, and 688 bp in size, respectively, and typical results are shown on Fig. 2. To confirm their identities, the PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Southern blotting with the 32P-labeled wt VP5, VP16, dUTPase, UL38, or CAT stuffer probe (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

DNA from purified recombinant viruses was analyzed by PCR, using an upper-strand oligonucleotide that binds at positions −293 to −274 relative to the VP5 cap site (upstream of the insertion site) and a second oligonucleotide that binds the lower strand in the VP5 leader region at positions +67 to +117 (downstream of the promoter insertion site). The PCR products of the wt VP5 promoter, UL38/VP5, dUTPase/VP5, the CAT stuffer, and VP16/VP5, are 410, 594, 758, 710, and 688 bp, respectively. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. MWM, molecular size markers (in base pairs).

Asymmetrically PCR-amplified DNA from all recombinant viruses was directly sequenced by using the VP5 primer, which binds in the VP5 leader region from positions +67 to +107 (10). Independent isolates were generated by separate transfections to ensure that promoter activity was not influenced by second-site mutations within the inserted region.

Analysis of the kinetics of the VP5 mRNA expressed under the control of the VP16, dUTPase, or UL38 promoter.

Recombinant viruses were used to infect RSF, and total RNA was isolated at various time points postinfection to assess the expression of VP5 mRNA under the control of the various promoters. The expression of wt VP16, wt dUTPase, wt UL38, and ICP27 mRNA was also measured as an internal control. Since the binding efficiency and the overall sensitivity of each primer differs, we made no attempt to compare the levels of various transcripts vis-à-vis each other. It is noteworthy, however, that the relative levels of VP5 mRNA expressed under the control of the various promoters generally reflected the strength of those promoters as determined in quantitative assays (36, 37).

VP5 mRNA was measured by primer extension, using a labeled probe extending from base +67 of the VP5 leader region to detect the expression of the VP16/VP5, dUTPase/VP5, or UL38/VP5 chimeric transcripts. This primer gives rise to 63-, 142-, and 158-nt bands for the substituted VP16, dUTPase, and UL38 promoters, respectively. No additional start sites were found among all of the recombinant viruses tested.

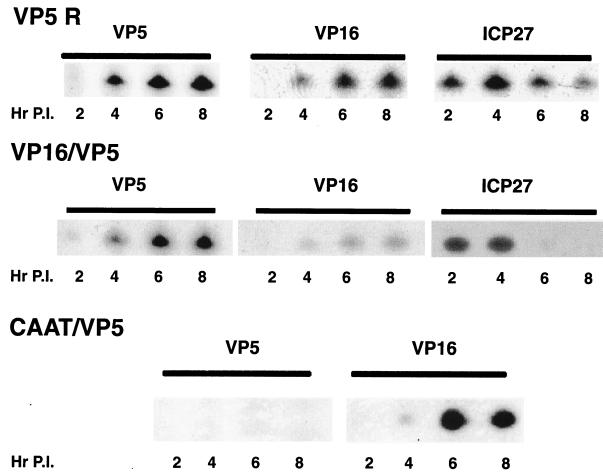

The VP5-rescued virus (VP5R) expressed the VP5 mRNA with the expected leaky-late kinetics, equivalent to those of wt VP16 mRNA (Fig. 3). Similarly, the VP16/VP5 recombinant virus expressed chimeric VP5 mRNA with the same kinetics as it expressed the wt VP16 mRNA, which is essentially equivalent to that for wt VP5 mRNA. It is evident that expression of the immediate-early ICP27 transcript, used as a control, was maximal at 4 h postinfection and shut off after that—normal kinetics for this immediate-early transcript. There was some variation in the ability to detect appreciable ICP27 transcript at late times in repeated experiments, but the range of variability was the same for all recombinant viruses assayed. On the other hand, the VP5-null virus containing the CAT stuffer virus did not express any detectable VP5 transcript, although this virus expressed the VP16 transcripts with normal kinetics. Thus, the VP16 promoter can functionally substitute for the inactive VP5 promoter.

FIG. 3.

Kinetics and levels of VP5 mRNA expression by the VP5-rescued (VP5 R), VP16/VP5, and CAT/VP5 (CAAT/VP5) recombinant viruses. RSF were infected with virus at an MOI of 5 PFU/cell, and total RNA was isolated at various time points postinfection (P.I.). Ten-microgram quantities of total RNA were analyzed by primer extension with a primer extending from the VP5 leader region (+67), to detect the chimera transcript, or with wt VP16 and ICP27 primers, used as internal controls.

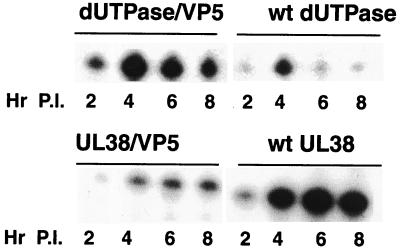

As shown on Fig. 4, the recombinant virus containing the dUTPase/VP5 promoter expressed its VP5-encoding transcripts with early or β kinetics identical to that of the internal wt dUTPase transcript. This expression peaked at 4 h postinfection and declined thereafter. The UL38/VP5-containing recombinant virus expressed its VP5-encoding mRNA with late kinetics, with rates increasing over time, consistent with the expression of wt UL38 transcript (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Kinetics and levels of chimeric VP5 mRNA expression by the dUTPase/VP5 or UL38/VP5 recombinant virus. RSF were infected with virus at an MOI of 5 PFU/cell, and total RNA was isolated at various time points postinfection (P.I.). Ten-microgram quantities of total RNA were analyzed by primer extension with a primer extending from the VP5 leader region (+67), (to detect the chimera transcript) or with wt dUTPase and wt UL38 primers (used as internal controls).

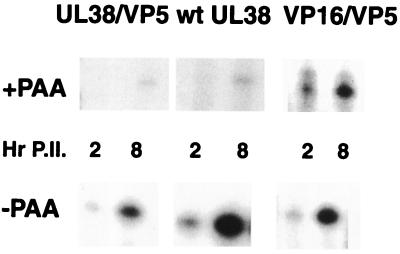

Analysis of the VP5 chimera transcripts in the presence of a DNA replication inhibitor.

The late kinetic class can be subdivided into two subclasses: the leaky-late (γ1) and the strict-late (γ2). Maximal expression of the late class requires viral DNA replication; however, the γ1 group is expressed at appreciable levels prior to the initiation of viral DNA synthesis or in its absence. For this reason, expression of proteins encoded by γ1 transcripts is not particularly sensitive to inhibitors of DNA replication. To confirm that expression of the VP5 transcripts under the control of the UL38 promoter followed strict-late (γ2) kinetics, recombinant viruses containing the UL38/VP5 promoter were used to infect RSF in the presence or absence of (400-μg/ml) phosphonoacetic acid (PAA). Total mRNA was isolated at 2 and 8 h postinfection and subjected to primer extension analyses as described above. Data are shown in Fig. 5. UL38 promoter-controlled VP5 transcription was markedly sensitive to the presence of PAA, as evidenced by very low levels of mRNA at 8 h postinfection in the presence of the drug. The same was observed with wt UL38 transcripts expressed in the same infection. On the other hand, the expression of the VP16/VP5 chimera transcript was appreciably less affected by PAA.

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analyses of total RNA from cells infected with the UL38/VP5 and VP16/VP5 recombinant viruses at 2 and 8 h postinfection in the presence (+) or absence (−) of PAA (400 μg/ml).

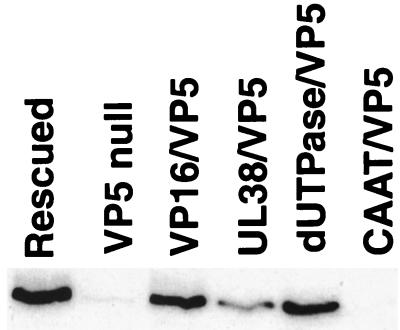

Expression of VP5 capsid protein following infection with recombinant viruses.

We used Western blot analysis to determine the amount of the VP5 capsid protein expressed in noncomplimenting cells 24 h following infection with these recombinant viruses. As shown in Fig. 6, the VP5R, VP16/VP5, and dUTPase/VP5 viruses expressed high levels of VP5 protein upon infection of Vero cells, while the UL38/VP5 virus expressed a somewhat smaller amount of the VP5 capsid protein. In contrast, as expected, essentially no VP5 protein was detected in cells infected with either the VP5-null or CAT/VP5 virus.

FIG. 6.

Western blot analysis of major capsid protein expression following infection with promoter-substituted viruses. RSF were infected with virus at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell and harvested at 24 h postinfection. Proteins were separated by SDS–6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The filters were probed for the expression of the VP5 capsid protein by using antibody NC1, provided by R. Eisenberg and G. Cohen.

Growth analyses on noncomplementing cell lines.

Various recombinant viruses were tested for growth on the complementing C32 and noncomplementing Vero cell lines. As shown in Table 1, titers for the recombinant viruses with the VP16, dUTPase, or the UL38 promoter controlling VP5 mRNA expression were essentially equivalent on both cell lines, Vero and C32. This was also the case with the VP5-rescued virus (VP5R). On the other hand, the VP5-null virus containing the CAT stuffer (CAT/VP5) failed to grow efficiently on Vero cells but grew to titers equivalent to those attained by the rescued virus on the complementing cell line.

TABLE 1.

Plaque formation efficiency of recombinant viruses on complementing and noncomplementing cellsa

| Virus | Virus titer (PFU per ml of stock) on:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| C32 cells | Vero cells | |

| VP5R | 5 × 108 | 7 × 108 |

| CAT/VP5 | 2 × 108 | 3 × 103 |

| VP16/VP5 | 8 × 108 | 9 × 108 |

| UL38/VP5 | 8 × 108 | 2 × 108 |

| dUTPase/VP5 | 4 × 108 | 4 × 108 |

All virus stocks were maintained on C32 cells. Titers of virus stocks were determined by plating dilutions of the stocks on C32 and Vero cells in parallel. The numbers are the averages of results from at least two separate experiments, and values were ±15% of the value shown.

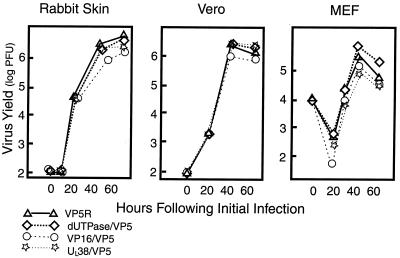

To determine the efficiency of virus replication on some different cell lines, viruses were infected at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell on RSF and Vero cells. A higher MOI of 1 PFU/cell was used with the mouse embryo fibroblasts. At 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection, yields of infectious virus were measured by plaque assay. All four recombinant viruses expressing VP5 replicated equivalently on these cells (Fig. 7). The CAT/VP5-null virus failed to replicate (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Multiple-step growth of promoter-substituted viruses. Virus was replicated in RSF, Vero cells, and mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEF). RSF and Vero cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell and harvested at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Mouse embryo fibroblasts were infected at an MOI of 1 PFU/cell and treated equivalently. Infectious virus was quantified by plaque assay on Vero cells.

To test for the ability of these recombinant viruses to replicate on serum-starved or quiescent cells, primary HLF were grown in medium with 0.25% FCS for 7 days or allowed to become quiescent by maintaining them under conditions of contact inhibition (31). Such cells were then infected with the various recombinant viruses at an MOI of 0.05 PFU/cell and incubated for 12 and 24 h. Infectious virus was freed from the infected-cell mass by three cycles of freeze-thawing and quantified by plaque assay. As shown in Table 2, all four viruses were able to replicate efficiently in both serum-starved and quiescent cells. The VP5-null virus containing the CAT stuffer did not replicate.

TABLE 2.

Replication of recombinant virus on serum-starved and quiescent HLF cellsa

| Virus | Virus yield (PFU/culture) on:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum-starved cells

|

Contact-inhibited cells

|

|||

| 12 h PI | 24 h PI | 12 h PI | 24 h PI | |

| VP5R | 3 × 105 | 7 × 106 | 1 × 105 | 9 × 106 |

| CAT/VP5 | NDb | ND | ND | ND |

| VP16/VP5 | 7 × 104 | 3 × 106 | 4 × 104 | 5 × 106 |

| UL38/VP5 | 2 × 104 | 3 × 106 | 5 × 104 | 6 × 106 |

| dUTPase/VP5 | 9 × 104 | 7 × 106 | 5 × 104 | 9 × 106 |

Cultures of 2.5 × 106 cells in 60-mm-diameter dishes were infected at an MOI of 0.05 PFU/cell. Virus yields are based on averages of data from a minimum of two independent experiments, and individual values were ± 20% of those shown. PI, postinfection.

ND, none detected.

DISCUSSION

While the early-to-late switch in gene expression and its correlation with gene function are hallmarks of DNA virus replication, the actual biological significance of altering the kinetics of expression of a given gene has not been widely studied in detail in infections with animal viruses. In the present communication, we have described an approach for investigating the biological manifestation resulting from altering the kinetic “signature” of a specific viral gene. We have used a VP5-null virus and a complementing cell line (C32) to construct mutants of HSV-1 in which the expression of the major capsid protein has been kinetically altered. In particular, we generated an inactive VP5 promoter by deleting the TATA box and initiator element (positions −36 to +20) and then inserted the strong early (UL50 or dUTPase), the strict-late (UL38), or a putatively equivalent leaky-late (VP16) promoter.

To ensure that there was no a priori selection for mutations that might encourage virus replication in a deleterious background, infectious DNAs from the VP5-null virus (K5dZ) and the modified BglII N were cotransfected into the complementing cell line to generate recombinant viruses. All subsequent rounds of virus purification were also carried out in the absence of any selection such as might be found by using a noncomplementing cell line for passage. The positive control was VP5 rescued (VP5R), with its own promoter, and a 300-bp DNA fragment derived from the bacterial CAT gene (CAT stuffer) was used in the deleted region of the promoter as a negative control.

Analyses of the kinetics and levels of VP5 mRNA expression in productively infected cells demonstrated that replacement of the TATA box and initiator element with the CAT stuffer resulted in a completely inactive promoter (Fig. 3). Promoter activity was restored by substituting the VP16 (βγ) promoter. We will show elsewhere (P. T. Lieu and E. K. Wagner, manuscript in preparation) that there are significant differences in the detailed functional architecture of this promoter and that of the wt VP5 promoter. Here, it suffices to observe that both the kinetics and levels of VP16/VP5 chimeric mRNAs were similar to those observed with VP5 mRNAs expressed by rescued virus. Thus, despite the variations in promoter architecture, promoters within the same kinetic class can readily substitute for one another.

In contrast, and as expected, when an early or β kinetic class promoter was inserted in the VP5 locus, the kinetics of the chimeric VP5-encoding transcript followed the early kinetic class; i.e., activity peaked at 4 h postinfection and then declined. Furthermore, insertion of the strict-late UL38 promoter resulted in the chimeric VP5-encoding mRNA accumulating with kinetics identical to that of wt UL38 transcripts. The strict-late kinetics of the VP5 transcript controlled by the UL38 promoter were confirmed by performing infections in the presence of a DNA replication inhibitor, PAA. It is clear that the expression of the chimeric VP5-encoding transcript was as sensitive to the action of PAA as was that of the wt UL38-encoding mRNA. This is in contrast to the observation that the VP16 promoter-controlled expression of VP5 mRNA was far less sensitive to PAA. These results are fully consistent with our model holding that promoter architectures are, in large part, responsible for controlling the expression of different classes of viral genes.

The expression of the VP5 capsid protein was detected by Western blot analysis with a VP5 polyclonal antibody supplied by R. Eisenberg and G. Cohen, and some differences in the levels of protein expressed was observed following infection with the various recombinant viruses. As shown in Fig. 6, the amounts of the VP5 capsid protein expressed by the VP16/VP5 and the dUTPase/VP5 viruses were essentially equivalent to that expressed by the VP5-rescued virus. In contrast, reproducibly less capsid protein was expressed in cells infected with the UL38/VP5 virus. While the VP5 capsid protein was readily detected by 4 h postinfection with the VP5R, dUTPase/VP5, and VP16/VP5 viruses, the protein was not detected until 8 h after infection with the UL38/VP5 virus (data not shown).

Despite these differences in the details of expression of the major capsid protein, we found that there was no significant difference in the efficiencies of replication of these various viruses in the cultured cells tested. As shown in Table 1, the three recombinant viruses expressing VP5 replicated to titers equivalent to that of the rescued wt virus on both complementing (C32) and noncomplementing (Vero) cells. The replication of the VP5-null virus containing the CAT stuffer was reduced by more than 5 logs. Extremely low-level replication of VP5-null virus on noncomplementing cells following its isolation from complementing cells was also observed by Desai et al. (3). This probably reflects a low level of recombination between the VP5-null virus and the chromosome of the complementing cell line. In addition, some virus growth may be a result of very limited expression of the VP5 transcript from an upstream or inappropriate promoter. Any such transcription was not detectable by primer extension.

Similarly, all VP5-expressing viruses replicated equivalently in multistep growth experiments using RSF, Vero cells, and mouse embryo fibroblasts. We also found that the VP5-expressing viruses all replicated efficiently in primary HLF maintained under suboptimal conditions, such as serum starvation induced by prolonged incubation in medium with 0.25% FCS or contact inhibition of growth.

These results, which were mildly surprising to us, suggest that replication of HSV in cultured cells is relatively insensitive to the exact kinetics of expression of the VP5 protein, at least under conditions in which it can be expressed abundantly during some window of time and accumulate. We have shown elsewhere that the dUTPase promoter is a strong one (19). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4, the maximum amount of the VP5 transcript accumulating at its peak time of expression is larger when controlled by the dUTPase promoter than when controlled by either the VP16 or UL38 promoter. Apparently, even though levels of the mRNA expressed early decline at later times, there is sufficient capacity for the synthesis of the capsid protein to attain maximum levels of virus production. Alternatively, the stability of VP5 protein is sufficient to maintain an adequate pool of protein late. This idea is supported by the fact that the level of the VP5 capsid protein detected after 24 h postinfection is equivalent in cells infected with either the dUTPase/VP5, the VP16/VP5, or the rescued wt virus.

Our data also suggest that the putatively premature attainment of high levels of VP5 capsid protein before the maximum synthesis of viral DNA had no obvious deleterious effect on production of infectious virus. Again, although the UL38/VP5 recombinant virus evidenced a clearly lower level of accumulation of VP5 capsid protein by Western blot analysis, this also had little or no effect on virus replication in the cultured cells tested. These observations suggest that, not surprisingly, the virus utilizes only a portion of the expressed capsid protein for assembly. Taken together, our data provide evidence that there is little stringency for the timing of appearance and levels of the major capsid protein in the complex process of virion morphogenesis, at least as measured by the formation of infectious virus.

While we have established that considerable latitude can be tolerated in the timing of the appearance of high levels of the VP5 capsid protein in the replication of HSV in cell culture, we do not think that this will be reflected in the process of virus infection and spread in the host. Analysis of the pathogenesis of these viruses in the animal, where there is a requirement for virus replication in differentiated cells, and tissues should reveal points and tissues for which the timing of expression of this protein is critical. Further, we are currently engaged in examining the effect of altering the kinetics of expression of the less abundant UL38 protein on virus replication. In this way, we expect to build a detailed analysis concerning the specific role of the kinetics of expression of selected viral genes in the replication process as a whole.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. Rice provided invaluable technical assistance. We thank P. Desai and S. Person for providing the cell line and VP5-null virus. We also thank R. Eisenberg and G. Cohen for providing the NC1 antibodies. G. B. Devi-Rao, M. Rice, S. Aguilar, and S. Stingly provided useful input and critical reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grant CA11861 from the National Institutes of Health and by a predoctoral fellowship to P. T. Lieu from a Gene Therapy for Cancer Training grant provided by the University of California.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ace C I, McKee T A, Ryan J M, Cameron J M, Preston C M. Construction and characterization of a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant unable to transinduce immediate-early gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:2260–2269. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2260-2269.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair E D, Snowden B W. Comparative analysis of the parameters that regulate expression from promoters of two late HSV-1 gene products. In: Wagner E K, editor. Herpesvirus transcription and its regulation. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai P, DeLuca N A, Glorioso J C, Person S. Mutations in herpes simplex virus type 1 genes encoding VP5 and VP23 abrogate capsid formation and cleavage of replicated DNA. J Virol. 1993;67:1357–1364. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1357-1364.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flanagan W M, Papavassiliou A G, Rice M, Hecht L B, Silverstein S, Wagner E K. Analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 promoter controlling the expression of UL38, a true late gene involved in capsid assembly. J Virol. 1991;65:769–786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.769-786.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flanagan W M, Wagner E K. A bi-functional reporter plasmid for the simultaneous transient expression assay of two herpes simplex virus promoters. Virus Genes. 1987;1:61–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00125686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godowski P J, Knipe D M. Transcriptional control of herpesvirus gene expression: gene functions required for positive and negative regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:256–260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzowski J F, Singh J, Wagner E K. Transcriptional activation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL38 promoter conferred by the cis-acting downstream activation sequence is mediated by a cellular transcription factor. J Virol. 1994;68:7774–7789. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7774-7789.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guzowski J F, Wagner E K. Mutational analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 strict late UL38 promoter/leader reveals two regions critical in transcriptional regulation. J Virol. 1993;67:5098–5108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5098-5108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homa F L, Krikos A, Glorioso J C, Levine M. Functional analysis of regulatory regions controlling strict late HSV gene expression. In: Wagner E K, editor. Herpesvirus transcription and its regulation. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C-J, Goodart S A, Rice M K, Guzowski J F, Wagner E K. Mutational analysis of sequences downstream of the TATA box of the herpes simplex virus type 1 major capsid protein (VP5/UL19) promoter. J Virol. 1993;67:5109–5116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5109-5116.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang C-J, Wagner E K. The herpes simplex virus type 1 major capsid protein (VP5-UL19) promoter contains two cis-acting elements influencing late expression. J Virol. 1994;68:5738–5747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5738-5747.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imbalzano A N, DeLuca N A. Substitution of a TATA box from a herpes simplex virus late gene in the viral thymidine kinase promoter alters ICP4 inducibility but not temporal expression. J Virol. 1992;66:5453–5463. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5453-5463.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan R, Schang L, Schaffer P A. Transactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early gene expression by virion-associated factors is blocked by an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent protein kinases. J Virol. 1999;73:8843–8847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8843-8847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junejo F, MacLean A R, Brown S M. Sequence analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 strain 17 variants 1704, 1705, and 1706 with respect to their origin and effect on the latency-associated transcript sequence. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2311–2315. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamberti C, Weller S K. The herpes simplex virus type 1 cleavage/packaging protein, UL32, is involved in efficient localization of capsids to replication compartments. J Virol. 1998;72:2463–2473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2463-2473.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieu P T, Pande N T, Rice M K, Wagner E K. The exchange of cognate TATA boxes results in a corresponding change in the strength of two HSV-1 early promoters. Virus Genes. 1999;20:5–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1008108121028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGeoch D J. Correlation between HSV-1 DNA sequence and viral transcription maps. In: Wagner E K, editor. Herpesvirus transcription and its regulation. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Hare P, Goding C R, Haigh A. Direct combinatorial interaction between a herpes simplex virus regulatory protein and a cellular octamer-binding factor mediates specific induction of virus immediate-early gene expression. EMBO J. 1988;7:4231–4238. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pande N T. Functional analysis of two early gene promoters of herpes simplex virus type 1. Ph.D. dissertation. University of California; 1997. , Irvine. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Person S, Desai P. Capsids are formed in a mutant virus blocked at the maturation site of the UL26 and UL26.5 open reading frames of herpes simplex virus type 1 but are not formed in a null mutant of UL38 (VP19C) Virology. 1998;242:193–203. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.9005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roizman B. HSV gene functions: what have we learned that could be generally applicable to its near and distant cousins? Acta Virol. 1999;43:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roizman B, Tognon M. Restriction endonuclease patterns of herpes simplex virus DNA: application to diagnosis and molecular epidemiology. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1983;104:273–286. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68949-9_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandri-Goldin R M, Goldin A L, Holland L E, Glorioso J C, Levine M. Expression of herpes simplex virus β and γ genes integrated in mammalian cells and their induction by an α gene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:2028–2044. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.11.2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sears A E, Roizman B. Amplification by host cell factors of a sequence contained within the herpes simplex virus 1 genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9441–9444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw P, Knez J, Capone J P. Amino acid substitution in the herpes simplex virus transactivator VP16 uncouple direct protein-protein interaction and DNA binding from complex assembly and transactivation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29030–29037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.29030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silver S, Roizman B. γ2-Thymidine kinase chimeras are identically transcribed but regulated as γ2 genes in herpes simplex virus genomes and as β genes in cell genomes. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:518–528. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.3.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh J, Wagner E K. Herpes simplex virus recombination vectors designed to allow insertion of modified promoters into transcriptionally “neutral” segments of the viral genome. Virus Genes. 1995;10:127–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01702593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steffy K R, Weir J P. Mutational analysis of two herpes simplex virus type 1 late promoters. J Virol. 1991;65:6454–6460. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6454-6460.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takasu T, Furuta Y, Sato K C, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y, Nagashima K. Detection of latent herpes simplex virus DNA and RNA in human geniculate ganglia by the polymerase chain reaction. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 1992;112:1004–1011. doi: 10.3109/00016489209137502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomsen D R, Newcomb W W, Brown J C, Homa F L. Assembly of the herpes simplex virus capsid: requirement for the carboxyl-terminal twenty-five amino acids of the proteins encoded by the UL26 and UL26.5 genes. J Virol. 1995;69:3690–3703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3690-3703.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Sant C, Kawaguchi Y, Roizman B. A single amino acid substitution in the cyclin D binding domain of the infected cell protein no. 0 abrogates the neuroinvasiveness of herpes simplex virus without affecting its ability to replicate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8184–8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner E K. Transcription patterns in herpes simplex virus infections. In: Klein G, editor. Advances in viral oncology. III. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 239–270. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner E K. Herpes simplex virus—molecular biology. In: Webster R G, Granoff A, editors. Encyclopedia of virology. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 686–697. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner E K, Anderson K P, Costa R H, Devi-Rao G B, Gaylord B, Holland L E, Stringer J R, Tribble L. Isolation and characterization of HSV-1 mRNA. In: Becker Y, editor. Herpesvirus DNA: recent studies on the internal organization and replication of the viral genome. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff B.V.; 1981. pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner E K, Costa R H, Devi-Rao G B, Draper K, Frink R J, Hall L, Rice M, Steinhart W. Herpesvirus mRNA. In: Becker Y, editor. Developments in molecular virology. VI. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner E K, Guzowski J F, Singh J. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus genome during productive and latent infection. In: Cohen W E, Moldave K, editors. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 123–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner E K, Petroski M D, Pande N T, Lieu P T, Rice M K. Analysis of factors influencing the kinetics of herpes simplex virus transcript expression utilizing recombinant virus. Methods. 1998;16:105–116. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinheimer S P, McKnight S L. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls establish the cascade of herpes simplex virus protein synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:819–833. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]