The randomised controlled trial is the most scientifically rigorous way of evaluating interventions whose effects on important clinical outcomes are uncertain.1 Before conducting such a trial, investigators should undertake a systematic review of the evidence from existing trials, including, if appropriate, a meta-analysis. This prevents trials being carried out unnecessarily when the answer to the clinical question is already known. A priori power calculations should be made to determine how many participants will be required to answer the research question,2 and this process is increasingly being required by research ethics committees and funding bodies, among others.3 Nevertheless, under some circumstances recruitment to a trial may be halted before the planned sample size has been reached because

Funding has run out or further recruitment has become impossible because of a lack of interest in the participating centres—“trial fatigue”

The internal evidence emerging from accumulating trial data suggests that continuing would be unethical4

External evidence indicates that the trial should be halted.5

The process for stopping a trial early because of indications from internal data is well accepted and recognised and the statistical methodology has been discussed at length, but this is not the case for external evidence. The process by which trial investigators should consider external evidence and make decisions concerning further recruitment is unclear.

Summary points

Principal investigators of clinical trials should be responsible for obtaining relevant information emerging from other studies

Investigators should seek unpublished confidential information, but this requires sensitive handling

Meta-analysis is useful for incorporating ongoing trial data with existing and emerging evidence

The trial data monitoring committee is responsible for reviewing both internal and external information, but the trial steering committee should decide whether to modify or stop a trial

Methods

We describe our recent experience of stopping a large international trial because of external evidence that emerged after the trial had begun. Our aim is to illustrate some of the problems we encountered. On the basis of this experience and relevant published reports, we make practical suggestions for making this element of data monitoring more explicit in future trials.

The trial

The antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial was set up to evaluate the use of thyrotropin releasing hormone combined with corticosteroids in women at risk of preterm labour.6 When the study was being planned, six randomised controlled trials of thyrotropin releasing hormone had already been performed and had been combined in a systematic review and meta-analysis.7 This review suggested that thyrotropin releasing hormone might reduce the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (overall relative risk 0.77; 95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.98) in babies born to mothers who had been treated with thyrotropin releasing hormone. However, there were three problems associated with the trial evidence. Firstly, many of the studies only reported outcomes in a subset of babies born within 10 days of their mothers' recruitment to the trial. Secondly, respiratory distress syndrome is a surrogate measure of neonatal morbidity. Thirdly, the trials were too small to be able to evaluate the effect of thyrotropin releasing hormone on more substantive outcome measures such as neonatal mortality or chronic lung disease. The only trial of a reasonable size was the Australian collaborative trial of antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone.8 However, this study used a lower dose of thyrotropin releasing hormone than the previous ones and showed no benefit for babies whose mothers had received active treatment.

Definitive answer

The antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial was designed to provide a definitive answer to whether the treatment was beneficial. It sought to recruit approximately 3800 women to evaluate the effect of thyrotropin releasing hormone compared with placebo on death and chronic lung disease. Approximately 200 centres in at least 10 different countries were expected to recruit patients. The European Union's biomed programme and the UK Medical Research Council supported the trial. In 1994-5, during the planning stage, the trial investigators knew of two other ongoing randomised controlled trials that were using the same intervention in the same group of women. However, these trials were smaller and had chosen respiratory distress syndrome as their primary outcome. Contact was made with the trial investigators of both trials in order to monitor their progress.

The start of the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial was delayed until the middle of 1996 because of prolonged negotiations with the pharmaceutical company which was donating the thyrotropin releasing hormone and placebo. By early 1997, however, 23 centres were recruiting subjects, 55 centres had research ethics committee approval and were waiting to start recruitment, and a further 69 centres were applying for this approval. The centres were from 10 countries and 225 women had been randomised.

New external evidence

In the first half of 1997, new external information came from three sources. Early in the year, confidential information about the one year follow up of the Australian trial became available to one of the principal investigators of the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial as part of a journal's peer review process. The data indicated that babies exposed to thyrotropin releasing hormone in utero had lower developmental scores at one year than the placebo group. The steering committee of the Australian trial made this information available to all the principal investigators of the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial. When the Australian data were eventually published, the principal investigators of the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial called an international telephone conference with the Australian study's steering committee.9 Because the follow up data from the Australian trial were consistent with its short term results and the steering committee of the Australian study urged the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial investigators to continue, it was agreed to continue recruitment but to draw the Australian trial data to the attention of collaborating centres.

In May, the results of the two other trials were presented orally at a conference in Washington. Neither trial detected any benefit of thyrotropin releasing hormone on respiratory distress syndrome in neonates.

Reviewing the evidence

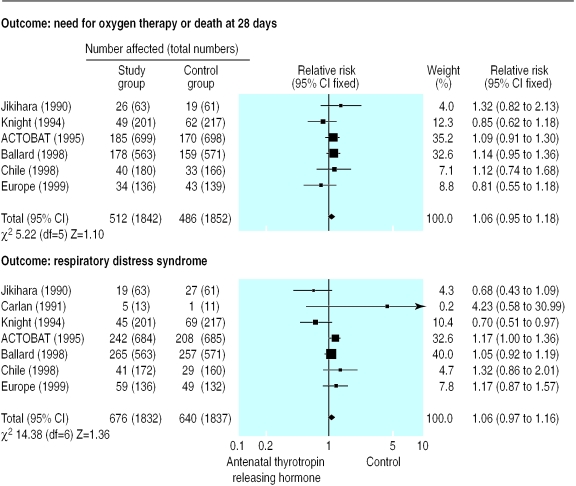

Because of these results, the principal investigators suspended the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial until its data monitoring and trial steering committees could meet. In preparation for these meetings, the data from the new trials were added to the existing meta-analysis in which data from all trials that had reported their intention to treat analysis were combined (figure). This information, together with the analysis of the first 225 women recruited to the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial, was given to the data monitoring committee, which had been urgently convened in May 1997.

The committee's terms of reference had been included in the original trial protocol. The statistical criteria for changing the protocol or stopping early were based on the Peto rule.10 The data monitoring committee recommended that the trial protocol be amended to allow the trial to continue in a subgroup of women who deliver within 10 days of receiving thyrotropin releasing hormone or placebo, if such a group could be identified reliably at randomisation. (This identification was not possible.)

Steering committee deliberations

The international steering committee met a few days later to discuss the report of the data monitoring committee, the implications of the two, as yet unpublished, trials of thyrotropin releasing hormone, and the follow up of the Australian trial. The first part of the meeting was spent discussing the process by which the new data would be viewed. It was agreed that a meta-analysis of the trials that included an intention to treat analysis would be considered. The trial steering committee agreed to consider stopping the trial if the new meta-analysis showed that the incidences of death and chronic lung disease were significantly greater in the group receiving thyrotropin releasing hormone than the placebo group or if there was evidence that any potential benefit in the thyrotropin releasing hormone group was too small to be considered clinically useful. The committee agreed that it would be unnecessary to continue the trial to show conclusively that thyrotropin releasing hormone was harmful because the treatment was not used widely.

The updated meta-analysis suggested that if thyrotropin releasing hormone was of any benefit, the relative reduction in the incidence of death or chronic lung disease was unlikely to be more than 5%. The trial size of 3800 had been based on detecting a relative difference of 30%, as this was felt to be an important difference that would change clinical practice. More than 100 000 women would have to be recruited, however, if the trial had to show a 5% relative difference (assuming the incidence of the primary outcome was 10%, as was assumed in the initial sample size estimate). After lengthy discussion, the trial steering committee decided that there was no justification for continuing the trial and recruitment was stopped.

Winding down process

A letter explaining why the trial had finished earlier than expected was sent to all the recruiting centres and the women who had so far been recruited. The staff financed by the grant had their contracts shortened. The women and babies recruited were followed up as specified in the protocol, and the results were prepared and analysed as planned.

Discussion

This example raises general questions about formalising the role of external evidence in the monitoring of trials—how should this information be collected, who should collect it, and how should external evidence be incorporated into a steering committee's decision making process? We focus here on the practicalities of this process, which could be applied within the statistical framework of “classical” or “bayesian” stopping rules.11 In the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial, three main groups were involved in this process—the principal investigators, the trial steering committee, and the data monitoring committee.

Role of the principal investigators

The principal investigators were the most closely involved with the trial and the subject area. By staying in close contact with investigators in related trials and by working cooperatively they learned about new external information before it was published. However, because some of this information was given to them in confidence, it could not be disseminated until it had been published in a scientific journal. Even after information had been presented at a scientific meeting, widespread written dissemination was not allowed in case this prejudiced subsequent journal publication. With one exception (see below), the principal investigators were not aware of the interim results of the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial.

Role of the steering committee

In contrast to the principal investigators, the steering committee in this trial was international and large (although this situation may be uncommon). This allowed the expression of a considerable breadth of views but meant that it was not feasible to meet often. In addition, the trial steering committee included independent members who could not be expected to devote large amounts of time to ascertaining external evidence. Rather, the role of the trial steering committee was to receive and interpret evidence before making decisions. This role has been formalised in the revised terms of reference for the trial steering committee of a trial funded by the MRC. These include the statement: “To review at regular intervals relevant information from other sources, and to consider the recommendations of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.”3

Role of the data monitoring committee

In general, the involvement of the data monitoring committee is intermittent and its principal responsibility is to consider the accumulating data from within the trial. In the case of the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial, one of the principal investigators (PB), working with the trial statistician, provided the data monitoring committee with these data in confidence. This principal investigator was not involved with the recruitment of women to the trial.12 Details of the external information were also provided in the report to the data monitoring committee. In this case, there were so few data from the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial that almost the same information was available to the data monitoring committee, the principal investigators, and the trial steering committee. Usually, however, only the data monitoring committee and those who service it will have this comprehensive overview.

Suggestions

On the basis of this experience, we suggest the following division of responsibilities for including external information into the trial monitoring process. The principal investigators, a small group of people who are closely involved in the trial and the subject area, should be responsible for ascertaining any external information in as timely a fashion as possible. This process will be helped by regular updating of the Cochrane database of reviews (at least where a review is in existence), although personal contacts may speed up this process even more. The role of information provided confidentially (whether by the principal investigators of related trials, the peer review process by scientific journals, or other sources) presents an additional level of complexity, requiring sensitive discussions between the relevant parties.

A mechanism needs to be established for providing the chair of the data monitoring committee with any additional external information as it is ascertained. The decision to call a formal meeting of the data monitoring committee to consider additional information should rest with the chairperson of the data monitoring committee. In a rapidly moving area of research, a formal meta-analysis is likely to be the most appropriate way of presenting these data. The data monitoring committee is an independent group and the only body with full oversight of both the internal and external evidence. It is in the best position to make informed recommendations about whether it is ethical for a trial to continue recruiting subjects or whether the protocol should be amended. In making recommendations based on all available evidence, the data monitoring committee can use statistical rules that are similar to those used in considering evidence from a single trial. Having received such a recommendation, it is the responsibility of the trial steering committee to make the final decision about the future of the trial.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Meta-analysis of thyrotropin releasing hormone treatment plus steroids compared with steroids alone

Acknowledgments

We thank Associate Professor Caroline Crowther and Professor Roberta Ballard for providing confidential information from their trials and Mr Ian White for commenting on the drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

Funding: PB is supported by the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Involvement in the antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone trial is outlined on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, editors. Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MRC guidelines for good clinical practice in clinical trials. London: Medical Research Council; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meinert CL. Clinical trials: design, conduct and analysis. Monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics. Vol. 8. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pocock SJ. The role of external evidence in data monitoring of a clinical trial. Stat Med. 1996;15:1285–1293. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960630)15:12<1285::AID-SIM309>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfirevic Z, Boer K, Brocklehurst P, Bulmer M, Elbourne D, Kok J, et al. Two trials of antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone for fetal maturation: stopping before the due date. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:898–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowther C, Alfirevic Z Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Library. Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software; 1996. Antenatal thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) prior to preterm delivery. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACTOBAT Study Group. Australian collaborative trial of antenatal thyrotropin-releasing hormone (ACTOBAT) for prevention of neonatal respiratory disease. Lancet. 1995;345:877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowther CA, Hillier JE, Haslam RR, Robinson JS ACTOBAT Study Group. Australian collaborative trial of antenatal thyrotropin-releasing hormone: adverse effects at 12-month follow up. Pediatrics. 1997;99:311–317. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. 1. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegelhalter DJ, Freedman LS, Parmar MKB. Bayesian approaches to randomised trials. J R Stat Soc (A) 1994;157:357–416. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meinert CL. Clinical trials and treatment effects monitoring. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:515–522. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.