Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We evaluated associations between plasma and neuroimaging‐derived biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias and the impact of health‐related comorbidities.

METHODS

We examined plasma biomarkers (neurofilament light chain, glial fibrillary acidic protein, amyloid beta [Aβ] 42/40, phosphorylated tau 181) and neuroimaging measures of amyloid deposition (Aβ‐positron emission tomography [PET]), total brain volume, white matter hyperintensity volume, diffusion‐weighted fractional anisotropy, and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging free water. Participants were adjudicated as cognitively unimpaired (CU; N = 299), mild cognitive impairment (MCI; N = 192), or dementia (DEM; N = 65). Biomarkers were compared across groups stratified by diagnosis, sex, race, and APOE ε4 carrier status. General linear models examined plasma‐imaging associations before and after adjusting for demographics (age, sex, race, education), APOE ε4 status, medications, diagnosis, and other factors (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], body mass index [BMI]).

RESULTS

Plasma biomarkers differed across diagnostic groups (DEM > MCI > CU), were altered in Aβ‐PET‐positive individuals, and were associated with poorer brain health and kidney function.

DISCUSSION

eGFR and BMI did not substantially impact associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers.

Highlights

Plasma biomarkers differ across diagnostic groups (DEM > MCI > CU) and are altered in Aβ‐PET‐positive individuals.

Altered plasma biomarker levels are associated with poorer brain health and kidney function.

Plasma and neuroimaging biomarker associations are largely independent of comorbidities.

Keywords: dementias, neuroimaging, plasma biomarkers

1. INTRODUCTION

The need for enhanced detection earlier in the course of dementia by minimally invasive means has ignited a growing interest in blood‐based biomarkers, which have advantages over cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or imaging biomarkers due to the relative ease of collection and/or reduced expense. Plasma biomarkers are obtained via a blood draw and thus reduce the burden placed on study participants, limiting the need to undergo more invasive procedures (eg, lumbar puncture). Plasma biomarkers sensitive to both age‐ and dementia‐related neuropathological change include plasma amyloid beta 1‐40 (Aβ40) and 1‐42 (Aβ42), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neurofilament light chain (NfL), and phosphorylated tau 181 (p‐tau181). Plasma‐derived analytes of amyloid (Aβ40, Aβ42) and p‐tau181 are AD‐specific. Conversely, NfL and GFAP are non‐specific markers of axonal neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation that contribute to cognitive impairment and mixed pathological forms of dementia. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4

Several health‐related risk factors and comorbidities can elevate or lower plasma biomarker levels through physiological actions, thereby impacting the diagnostic accuracy of these biomarkers for AD pathology. For example, previous studies showed that chronic kidney disease (CKD) was associated with altered levels of all AD plasma biomarkers and that body mass index (BMI) was associated with lower levels. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Compromised filtration of plasma/blood AD biomarkers due to kidney dysfunction is a primary concern even in individuals without CKD. 5 , 6

The degree to which Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD)‐related plasma biomarkers are associated with well‐established imaging biomarkers, not limited to amyloid deposition, of AD/ADRD in community‐dwelling cohorts is uncertain. Further, comorbid health complications (eg, compromised kidney functioning) with the potential to alter detectable levels of plasma analytes 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 may impact associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers of ADRD. At present, it is uncertain how demographic factors such as age, sex, and race may alter associations between plasma and imaging biomarkers in the context of comorbid health complications. Thus, this study sought to examine associations between AD/ADRD plasma biomarkers (Aβ42/Aβ40, p‐tau181, GFAP, and NfL) and neuroimaging measures of amyloid deposition (Aβ‐PET), total brain volume (BVOL), global white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume, diffusion‐weighted fractional anisotropy (FA), and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) free water (FW; white matter). Ultimately, this study sought to understand better how clinical, physiological, and pathological factors alter levels of plasma biomarkers and the extent to which such factors may impact associations with well‐established imaging biomarkers of AD/ADRD in a sample of community‐dwelling participants.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Participants

We examined cross‐sectional associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers in a sample (N = 556) of cognitively unimpaired (CU) participants (N = 299) and individuals adjudicated as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI; N = 192) or dementia (DEM; N = 65; Table 1). All participants were enrolled in the Wake Forest Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC) Clinical Core's Healthy Brain Study (HBS) focused on recruiting CU participants as well as those in preclinical stages of dementia. As previously described, 9 adults between the ages of 55 and 85 were recruited from the surrounding community and by referral through our memory clinic into the HBS (2016 to 2022) with oversight by the Outreach, Engagement & Recruitment Core of the Wake Forest ADRC. Participants underwent a standard evaluation, including the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) protocol for clinical research data collection, clinical exams, neurocognitive testing, neuroimaging, and genotyping for the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele. The Wake Forest Institutional Review Board approved all activities as described; written informed consent was obtained for all participants and/or their legally authorized representatives to voluntarily participate in this research study. No participants received or were recruited with the intent of receiving or being recommended for disease‐modifying treatments or therapies. No participants were referred to our study for treatment. Self‐reported race/ethnicity (eg, Black/White; non‐Hispanic) and sex (eg, male/female) constructs were examined as dichotomous variables. APOE genotype was obtained by Taqman using single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs429358 and rs7412) to determine haplotypes of ε2, ε3, and ε4. APOE was dichotomized to represent the presence or absence of one or more ε4 alleles (eg, carrier vs non‐carrier; APOE ε4). Exclusion criteria for recruitment into the HBS included large vessel stroke (participants with lacunae or small vessel ischemic disease were eligible); other significant neurologic diseases and uncontrolled chronic medical or psychiatric conditions (such as advanced liver or severe kidney disease [see Section 2.4.4 below for more details]; poorly controlled congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or sleep apnea, active cancer treatment, uncontrolled clinical depression, or psychiatric illness; current use of insulin; and history of substance abuse or heavy alcohol consumption within preceding 10 years). HBS participants with a current or active history of traumatic brain injury (N = 15), myocardial infarction (N = 21), or cerebral stroke (N = 5) 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 were excluded from analyses.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Overall, N = 556 a | CU, N = 299 a | MCI, N = 192 a | DEM, N = 65 a | p b | q c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70 (63, 76) | 68 (62, 73) | 71 (65, 77) | 73 (66, 78) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female | 369 (66%) | 217 (73%) | 116 (60%) | 36 (55%) | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| Race | 0.027 | 0.036 | ||||

| White | 444 (80%) | 243 (81%) | 145 (76%) | 56 (86%) | ||

| Black | 105 (19%) | 51 (17%) | 46 (24%) | 8 (12%) | ||

| Asian | 5 (0.9%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| American Indian | 2 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | ||

| Education | 16 (14, 18) | 16 (14, 18) | 16 (13, 18) | 16 (13, 18) | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| APOE ε4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Carrier | 182 (34%) | 80 (28%) | 69 (37%) | 33 (53%) | ||

| Non‐carrier | 356 (66%) | 210 (72%) | 117 (63%) | 29 (47%) | ||

| N (missing) | 538 (18) | 290 (9) | 186 (6) | 62 (3) | ||

| Health factors | ||||||

| BMI | 26.7 (24.1, 30.7) | 26.6 (23.9, 30.9) | 27.3 (24.8, 31.1) | 25.5 (23.4, 28.5) | 0.021 | 0.03 |

| eGFR | 75 (65, 86) | 76 (65, 87) | 75 (65, 85) | 73 (65, 83) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| N (missing) | 410 (146) | 211 (88) | 144 (48) | 55 (10) | ||

| Plasma biomarkers | ||||||

| NfL(pg/mL) | 14 (10, 20) | 13 (9, 17) | 15 (11, 21) | 20 (15, 29) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (missing) | 549 (7) | 295 (4) | 190 (2) | 64 (1) | ||

| GFAP(pg/mL) | 118 (83, 168) | 107 (76, 145) | 118 (87, 184) | 190 (149, 247) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (missing) | 551 (5) | 296 (3) | 190 (2) | 65 (0) | ||

| Aβ42/40 | 0.053 (0.046, 0.060) | 0.055 (0.049, 0.062) | 0.051 (0.044, 0.059) | 0.048 (0.044, 0.053) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (missing) | 552 (4) | 296 (3) | 191 (1) | 65 (0) | ||

| p‐tau181(pg/mL) | 2.89 (2.18, 4.06) | 2.58 (2.10, 3.37) | 3.01 (2.17, 4.37) | 4.77 (3.73, 6.33) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (missing) | 551 (5) | 297 (2) | 190 (2) | 64 (1) | ||

| Plasma sum d | −0.56 (–2.12, 1.77) | −1.26 (–2.44, 0.37) | −0.17 (–1.87, 2.37) | 2.41 (1.23, 4.78) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Imaging biomarkers | ||||||

| BVOL | 0.71 (0.68, 0.73) | 0.72 (0.69, 0.74) | 0.70 (0.68, 0.73) | 0.68 (0.65, 0.70) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (missing) | 524 (32) | 286 (13) | 177 (15) | 61 (4) | ||

| WMH | −1.55 (−2.24, −0.68) | −1.76 (−2.45, −1.15) | −1.20 (−1.94, −0.32s) | −0.78 (−1.67, −0.22) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (Missing) | 524 (32) | 286 (13) | 177 (15) | 61 (4) | ||

| FA | 0.510 (0.494, 0.522) | 0.513 (0.496, 0.526) | 0.505 (0.492, 0.519) | 0.512 (0.489, 0.521) | 0.017 | 0.019 |

| N (Missing) | 469 (87) | 259 (40) | 158 (34) | 52 (13) | ||

| FW | 0.163 (0.149, 0.182) | 0.160 (0.146, 0.177) | 0.166 (0.150, 0.188) | 0.179 (0.163, 0.193) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (Missing) | 443 (113) | 243 (56) | 150 (42) | 50 (15) | ||

| Aβ‐PET (SUVr) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.66) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.17) | 1.24 (1.10, 1.97) | 2.07 (1.46, 2.21) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| N (missing) | 140 (416) | 76 (223) | 44 (148) | 20 (45) | ||

| AβPOS‐PET | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 85 (61%) | 61 (80%) | 22 (50%) | 2 (10%) | ||

| Positive | 55 (39%) | 15 (20%) | 22 (50%) | 18 (90%) | ||

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AβPOS‐PET, Aβ‐PET positive (SUVr ≥ 1.21); BMI, body mass index; BVOL, total brain volume (adjusted for intracranial volume); CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fraction anisotropy; FW, free water; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light; NODDI, neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging; SUVr, standardized uptake value ratio; WMH, log‐transformed global white matter hyperintensity values.

n (%); median (IQR).

Pearson's chi‐squared test; Kruskal‐Wallis rank‐sum test; Fisher's exact test.

False discovery rate correction for multiple testing.

Sum Z‐scored composite of NfL, GFAP, Aβ42/40, and p‐tau181 (PLASMA SUM; see Methods).

2.2. Adjudication

An expert panel of investigators with extensive experience assessing cognitive status and diagnosing cognitive impairment in older adults, including neuropsychologists, neurologists, and geriatricians, provided adjudication of cognitive status. A consensus review of all available clinical, neuroimaging, and cognitive data followed current National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association guidelines for diagnosing MCI 15 or dementia 16 using clinical criteria.

2.3. Medications

Participants provided all prescription and over‐the‐counter medication use. 17 As previously described, 18 participants were considered on antihypertension therapy (HTNmed) if they reported recent or current use of antiadrenergic agents, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, beta‐blockers, calcium channel blocking agents, diuretics, vasodilators, angiotensin II inhibitors, or antihypertensive combination therapy agents. Statins and diabetic medications (DBmed) were permitted, except for insulin, which was an exclusion criterion at enrollment in the Wake Forest ADRC cohort. AD‐related medications (ADmed) were permitted. Approximately 62% of the sample reported current or recent use of one or more medications (CU = 51%; MCI = 71%; DEM = 85%; see Tables S1 and S2 for a full characterization of medication use in our sample).

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (eg, PubMed) sources and meeting abstracts and presentations. The degree to which Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD)‐related plasma biomarkers are associated with well‐established imaging biomarkers of AD/ADRD, not limited to amyloid deposition, and the extent to which plasma‐imaging association may be impacted by comorbid health complications (eg, compromised kidney functioning) in diverse cohorts is uncertain. Several publications assessing relationships between one or several plasma biomarkers and CSF pathology, comorbidities, diagnosis, and/or cognitive impairment are appropriately cited.

Interpretation: Our findings suggest that AD/ADRD plasma biomarkers are most associated with amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) deposition, followed by gray matter volume, and, to a lesser extent, with indices of white matter brain health in a diverse cohort.

Future directions: The combination of plasma and imaging biomarkers may help better establish biomarker‐specific cutoffs that both are clinically useful and generalize across studies and cohorts. Extending this work, incorporating additional analytes, including p‐tau217, we aim to establish a range of clinically relevant cutoffs (eg, thresholds) for plasma biomarkers in reference to established imaging biomarkers, demographics, and diagnostic information.

2.4. Biomarkers

2.4.1. Imaging biomarkers

Participants were scanned on a research‐dedicated 3T Siemens Skyra magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; 32‐channel head coil) scanner. We acquired T1, T2 fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging, diffusion‐weighted imaging diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and neurite orientation density and dispersion imaging (NODDI). Detailed image acquisition parameters have been published elsewhere. 9 , 18 Briefly, T1 processing included normalization and tissue segmentation using the CAT12 toolbox in SPM12 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Total intracranial and gray and white matter volumes were calculated using FreeSurfer version 7.2 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). Global WMH volume was segmented by the lesion growth algorithm (LGA) as implemented in the Lesion Segmentation Toolbox (LST) version 2.0.15 in SPM12 from co‐registered FLAIR and T1 images in native space. 19 WMH was adjusted for total intracranial volume and log‐transformed before analysis. 20 Global average DTI FA and NODDI FW values were computed using the average signal across all white matter tracts from the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) DTI atlas 21 overlaid on FA and NODDI images in template space.

2.4.2. Aβ‐PET Imaging

As previously described, 22 fibrillar Aβ brain deposition on PET was assessed with [11C]‐Pittsburgh compound B ([11C]PiB). 23 Following a computed tomography (CT) scan for attenuation correction, participants were injected with an intravenous bolus of ∼10mCi (approximately 370 MBq) [11C]PiB and scanned from 40 to 70 min (6×5‐min frames) following injection on a 64‐slice GE Discovery MI DR PET/CT scanner. All participants’ CT images were co‐registered to their structural MRI, and PET frames were co‐registered to MRI space using the affine matrix from the CT‐MRI co‐registration. Standardized uptake volume ratio (SUVr) images were co‐registered and resliced to the T1 structural MRI closest in time within ∼6 months on average (months: Mean = 0.98; standard deviation [SD] = 5.9). Aβ deposition (eg, [11C]PiB uptake visualized by PET) was quantified using a voxelwise SUVr, calculated as the PiB SUVr (40 to 70 min, cerebellar gray reference) signal averaged from a cortical meta‐region of interest sensitive to the early pathogenesis of AD relative to the uptake in the cerebellum, using FreeSurfer‐segmented regions. 22 , 24 Global [11C]PiB SUVR (Aβ‐PET) served as a biomarker of amyloid burden used in all analyses. Amyloid positivity (Aβ− and Aβ+) was a previously defined threshold (≥1.21 PiB SUVr). 25

2.4.3. Plasma AD biomarkers

Blood was collected from fasting participants and processed within 30 min of collection. For plasma, 10‐mL EDTA‐treated tubes were inverted 10 times and placed on wet ice before centrifuging at 2000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. Processed plasma was then aliquoted at a volume of 0.5 mL in 1.5‐mL into non‐sterile/skirted tubes (Fisherbrand cat. 02‐681‐338) and stored at −80°C. Batch shipments were sent to the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD) Biomarker Assay Laboratory on dry ice for analysis of plasma AD biomarkers. Assay plates contained 31 samples each and were balanced on age and sex along with collection visit for longitudinal samples. Thawed plasma samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min prior to analysis. Each sample was processed in duplicate per the manufacturer's instructions starting with 4× dilution with kit‐specific diluent on a Tecan Fluent 1080 automated liquid handler. Plasma NfL, GFAP, Aβ42, Aβ40, and p‐tau181 were analyzed utilizing the Quanterix Simoa Neurology 4‐Plex E and p‐tau181 version 2 Advantage Kits on a Quanterix Simoa HD‐X. All assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions are reported in units of picograms per milliliter (pg/mL). The kit provided quality control samples that were used to verify results and met quality criteria for analytical performance provided by the manufacturer. Pooled plasma reference (PPR) samples were analyzed on each plate to monitor assay performance in the laboratory (Table S3). We also assessed Aβ42/40 ratio 26 , 27 and a sum z‐score composite of plasma NfL, GFAP, Aβ42/40 (inverted), and p‐tau181 (PLASMA SUM). 28 Potentially implausible plasma biomarker values greater than four times the interquartile ratio (NfL = 3; GFAP = 6; Aβ42/40 = 1; p‐tau181 = 8 participants) were removed from analyses.

2.4.4. Assessment of comorbid health conditions

Kidney function was evaluated in blood from individuals free from severe CKD using the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; severe [Stage G4 and G5] CKD defined as eGFR < 30; also see participant characteristics) via Labcorp assay presented in units of mL/min/1.73 m2. Total BMI was calculated as weight (lb)/[height (in.)]2 × 703. BMI and eGFR were assessed as continuous variables. Medications were assessed as described earlier.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Associations between baseline plasma and neuroimaging data were assessed via unadjusted and adjusted general linear models (GLMs) using a model‐building approach. GLMs were constructed using robust standard errors; all continuous predictors (X) and outcomes (Y) were standardized (eg, centered, and scaled by their standard deviation) prior to analysis to permit cross‐model comparisons. Base (unadjusted) models linking plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers were compared with (1) a model adjusted exclusively for cardiometabolic factors (Adj: eGFR and BMI), (2) a fully adjusted model (F‐Adj) combining cardiometabolic factors with demographic variables (age, sex, race, education), APOE ε4 carrier status, and medication use (HTNmed, DBmed, ADmed), and, finally, (3) a fully adjusted model incorporating clinical diagnosis in order to account for disease stage. The relationship between plasma biomarker levels and Aβ‐PET positivity status was assessed using logistic regression. Raw unadjusted and Winsorized Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients are provided in the supplemental material for all primary continuous measures of interest. Additional supporting stratification analyses were performed to assess whether relationships between plasma and imaging biomarkers differed by sex, race, APOE ε4 carrier status, Aβ‐PET positivity, and clinical diagnosis. Stratification analyses are included in the supplemental material to provide a comprehensive assessment of biomarkers within the Wake Forest ADRC. Stratification analyses were performed using the non‐parametric Wilcoxon signed‐rank test to account for sampling biases. Corresponding effect sizes are reported to aid with interpretation in instances where there are a limited number of observations (eg, race) and are interpreted using established guidelines (Wilcoxon r: negligible < 0.10, small [S] = 0.10 to 0.30, moderate [M] = 0.30 to 0.50, large [L] > = 0.50; Cohen's d: negligible < 0.20, small < 0.50, medium < 0.80; large ≥ 0.80). 29 Multiple‐comparison corrections were performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (q). 30 All analyses were conducted in R (RStudio Team, 2020).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics overall and by cognitive diagnosis are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 69.89 ± 8.01; ∼19% self‐identified as Black/African American and 66% as female, and 34% were APOE ε4 carriers. MCI and DEM groups were slightly older on average compared to CU participants, and a larger proportion of males were classified as either MCI or DEM. A full summary of participant medication use can be found in the supplementary material (Table S1 and Table S2). Of those with eGFR data (74%; n = 410), ∼14.1% were classified as having normal‐high kidney function (n = 58; eGFR > = 90), ∼71.2% (n = 292) had mildly decreased eGFR values in the range of 60 to 90, and ∼14.7% (n = 60) had values between 32 (lowest) and 59. Approximately 86% of participants thus met the criteria (eGFR < 60) for monitoring of early‐stage kidney disease. 31 , 32 For BMI, 39% of the sample was characterized as overweight (n = 217; BMI > = 25 and < 30), 28.2% as obese (n = 157; BMI > 30), 1.44% as underweight (n = 8; BMI < 18.5), and 31.3% in the normal range (n = 174; BMI > = 18.5 and < 25) per established guidelines. Diagnostic groups differed on all measures assessed, except for eGFR. BMI was reduced in DEM and elevated in MCI participants compared to CU. Plasma biomarker levels were elevated in MCI and DEM participants (CU < MCI < DEM). Total brain volume and fractional anisotropy were reduced, while WMHs, NODDI FW, and Aβ‐PET deposition were elevated in MCI and DEM participants (CU < MCI < DEM).

3.2. Biomarkers

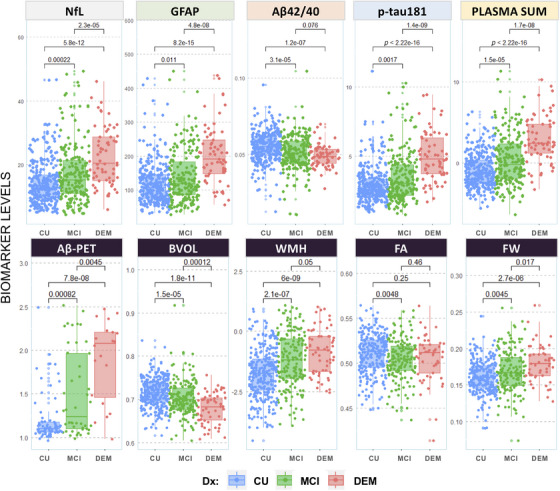

Plasma biomarkers were moderately correlated with each other (absolute rho = 0.20 to 0.61; all p < 0.001; see Table S4 for Pearson and Spearman correlation tables) and all significantly elevated (Aβ42/40 lower) in both DEM and MCI participants compared to CU (Figure 1; Table 1), as well as in Aβ‐PET‐positive (SUVr ≥ 1.21) compared to Aβ‐PET‐negative individuals (all p < 0.001; also see Figure S1). NfL, GFAP, p‐tau181, and PLASMA SUM significantly differed between MCI and DEM participants (all p < 0.05); Aβ42/40 did not differ between MCI and DEM (p = 0.076). All plasma biomarkers became more abnormal with advancing age (NfL: rho = 0.59, p −fdr < 0.001; GFAP: rho = 0.49, p −fdr < 0.001; Aβ42/40: rho = −0.26, p −fdr < 0.001; p‐tau181: rho = 0.36, p −fdr < 0.001; PLASMA SUM: rho = 0.51, p −fdr < 0.001). Except for Aβ42/40, plasma biomarkers were negatively associated with eGFR (NfL: rho = −0.41, p −fdr < 0.001; GFAP: rho = −0.33, p −fdr < 0.001; p‐tau181: rho = −0.29, p −fdr < 0.001; PLASMA SUM: rho = −0.35, p −fdr < 0.001) and with BMI (NfL: rho = −0.24, p −fdr < 0.001; GFAP: rho = −0.27, p −fdr < 0.001; p‐tau181: rho = −0.09, p −fdr < 0.001; PLASMA SUM: rho = −0.26, p −fdr < 0.001; Figure S2). Across diagnostic groups, eGFR and BMI were weakly negatively associated (r 2 = 0.01; p = 0.048); however, the negative association was strongest in CU participants (r 2 = 0.02; p = .042).

FIGURE 1.

Unadjusted group comparisons of plasma and neuroimaging measures by diagnostic status. Note that levels of plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers are compared across diagnostic groups (unadjusted; Dx: blue = CU; green = MCI; red = DEM). Aβ, amyloid beta; BVOL, brain volume (adjusted for intracranial volume); CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; Dx, diagnosis; FA, fractional anisotropy; FW, freewater; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light; NODDI, neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging; PLASMA SUM = sum Z‐scored composite of NfL, GFAP, Aβ42/40, and p‐tau181; WMH, log‐transformed global white matter hyperintensity volume.

3.3. Biomarker associations

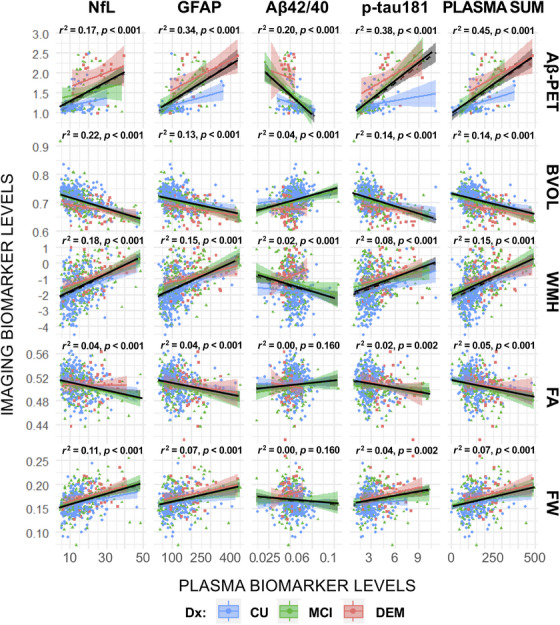

Plasma biomarkers were significantly associated with neuroimaging biomarkers in unadjusted models and in models adjusted for eGFR and BMI (all p < 0.05; Figure 2, Tables 2 and 3), with the exception of no associations between Aβ42/40 and both FA and FW. We found small to moderate associations in unadjusted models (Aβ‐PET: r2 = 0.17 to 38; BVOL: r2 = 0.04 to 22; WMH: r2 = 0.02 to 0.18; FA: r2 = 0.001 to 0.05; FW: r2 = 0.001 to 0.11). p‐tau181, GFAP, and PLASMA SUM were most strongly associated with Aβ‐PET deposition; NfL was most strongly associated with BVOL and WMH. In fully adjusted models, age, sex, race, APOE ε4 carrier status, and diagnosis differentially attenuated associations between Aβ42/40, p‐tau181, and NfL with imaging biomarkers, particularly for measures of white matter brain health (coefficients p < 0.05; see Table S5 and also see Stratification Analyses in the supplemental material). GFAP remained significantly associated with all neuroimaging biomarkers after covariate adjustment (p < 0.05); no Aβ42/40 associations with imaging biomarkers survived adjustment (p > 0.05). p‐tau181 remained significantly associated with Aβ‐PET and BVOL. Attenuation effects and model fit statistics are provided in the supplementary material (Table S6 and S7). Log‐transformation of plasma biomarkers did not modify the reported findings.

FIGURE 2.

Unadjusted linear relationships between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers. Note that unadjusted bivariate associations between plasma and neuroimaging markers are presented. r2 statistics and p values represent lines of best fit (solid black line) for the full sample of participants (irrespective of consensus diagnosis). Plasma‐neuroimaging associations, stratified by clinical diagnosis, are provided for comparison (blue = CU; green = MCI; red = DEM). Plasma biomarkers are most strongly associated with Aβ‐PET deposition. Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI); Aβ, amyloid beta; BVOL, brain volume (adjusted for intracranial volume); CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia; base, baseline unadjusted models; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; Dx, diagnosis; FA, fractional anisotropy; FW, free water; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light; NODDI, neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging; SUVr, standardized uptake volume ratio; WMH, log‐transformed global white matter hyperintensity volume; F‐Adj, adjusted models plus additional covariates (age, sex, race, education, APOE ε4 status, medications); F‐Adj*, fully adjusted models plus clinical diagnosis.

TABLE 2.

Models showing significant associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers before and after covariate adjustment and multiple‐comparisons correction.

| NfL | GFAP | Aβ42/40 | p‐tau181 | PLASMA SUM | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Adj | F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | Base | Adj | F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | Base | Adj | F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | Base | Adj | F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | Base | Adj | F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | |

| Aβ‐PET | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| BVOL | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| WMH | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| FA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||||||

| FW | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

Note: Base (unadjusted) and adjusted models associating plasma and neuroimaging‐derived biomarkers are presented. ±, plasma biomarker coefficient significant at p < 0.05, (+) positive association and (−) negative association.

Abbreviations: Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI); Aβ, amyloid beta; base, baseline unadjusted models; BVOL, brain volume (adjusted for intracranial volume); CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; Dx, diagnosis; FA, fractional anisotropy; F‐Adj, adjusted models plus additional covariates (age, sex, race, education, APOE ε4 status, medications). F‐Adj‐Dx., fully adjusted models plus clinical diagnosis; FW, free water; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; logWMH, log‐transformed global white matter hyperintensity values; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light chain; NODDI, neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging; SUVr, standardized uptake value ratio.

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted linear models assessing associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers.

| Aβ‐PET | Base (N = 140) | Adj (N = 81) | F‐Adj (N = 77) | F‐Adj‐Dx (N = 77) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | |

| NfL | 0.46 | 4.9 | 0.27, 0.65 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 2.6 | 0.08, 0.61 | 0.011 | 0.033 | 0.04 | 0.2 | −0.30, 0.38 | 0.800 | 0.800 | 0.01 | −0.1 | −0.30, 0.28 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| GFAP | 0.53 | 9.1 | 0.42, 0.65 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 5.7 | 0.32, 0.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 3.8 | 0.17, 0.54 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.35 | 4.3 | 0.18, 0.51 | 0.002 | 0.023 |

| Aβ42/40 | −0.46 | −3.7 | −0.61, −0.18 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.23 | −1.8 | −0.49, 0.02 | 0.039 | 0.059 | −0.06 | −0.7 | −0.24, 0.11 | 0.600 | 0.800 | −0.05 | −0.6 | −0.21, 0.12 | 0.700 | 0.800 |

| p‐tau181 | 0.55 | 5.6 | 0.36, 0.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 8.0 | 0.48, 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 8.2 | 0.42, 0.70 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 8.4 | 0.41, 0.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PLASMA SUM | 0.63 | 11.5 | 0.52, 0.74 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 8.22 | 0.50, 0.82 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 4.52 | 0.29, 0.74 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.48 | 4.34 | 0.26, 0.70 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| BVOL | Base (N = 524) | Adj (N = 383) | F‐Adj (N = 374) | F‐Adj‐Dx (N = 374) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | |

| NfL | −0.5 | −12.1 | −0.53, −0.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.46 | −8.9 | −0.56, −0.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.16 | −3.7 | −0.24, −0.07 | 0.002 | 0.005 | −0.14 | −3.3 | −0.23, −0.06 | 0.005 | 0.017 |

| GFAP | −0.4 | −9.4 | −0.42, −0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.33 | −6.7 | −0.41, −0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.13 | −3.5 | −0.20, −0.06 | 0.005 | 0.013 | −0.12 | −3.2 | −0.20, −0.05 | 0.009 | 0.028 |

| Aβ42/40 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 0.10, 0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 2.8 | 0.04, 0.21 | 0.013 | 0.019 | 0.01 | 0.2 | −0.06, 0.07 | 0.800 | 0.800 | 0.00 | 0.1 | −0.06, 0.07 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| p−tau181 | −0.4 | −7.7 | −0.45, −0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.30 | −5.9 | −0.41, −0.20 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.13 | −2.8 | −0.22, −0.04 | 0.006 | 0.015 | −0.12 | −2.5 | −0.21, −0.03 | 0.010 | 0.033 |

| PLASMA SUM | −0.5 | −13 | −0.54, −0.40 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.45 | −8.84 | −0.55, −0.35 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.17 | −3.85 | −0.26, −0.08 | <0.001 | 0.002 | −0.16 | −3.4 | −0.25, −0.07 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| WMH | Base (N = 524) | Adj (N = 383) | F‐Adj (N = 374) | F‐Adj‐Dx (N = 374) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | |

| NfL | 0.4 | 10.2 | 0.32, 0.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 7.2 | 0.27, 0.47 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 2.4 | 0.02, 0.23 | 0.024 | 0.100 | 0.09 | 1.7 | −0.01, 0.19 | 0.120 | 0.300 |

| GFAP | 0.4 | 10.4 | 0.30, 0.44 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 6.6 | 0.21, 0.40 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 3.4 | 0.07, 0.25 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.14 | 3.0 | 0.05, 0.23 | 0.007 | 0.031 |

| Aβ42/40 | −0.1 | −3.2 | −0.23, −0.05 | 0.600 | 0.600 | −0.10 | −2.0 | −0.19, 0.00 | 0.042 | 0.063 | 0.02 | −0.4 | −0.10, 0.06 | 0.700 | 0.800 | 0.00 | −0.1 | −0.08, 0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| p‐tau181 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 0.18, 0.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 4.0 | 0.10, 0.30 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 2.5 | 0.03, 0.22 | 0.013 | 0.053 | 0.10 | 2.0 | 0.00, 0.20 | 0.048 | 0.200 |

| PLASMA SUM | 0.41 | 11.3 | 0.34, 0.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.36 | 7.79 | 0.27, 0.45 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 3.37 | 0.07, 0.28 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.14 | 2.62 | 0.04, 0.25 | 0.013 | 0.041 |

| FA | Base (N = 469) | Adj (N = 346) | F‐Adj (N = 339) | F‐Adj‐Dx (N = 339) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | |

| NfL | −0.2 | −4.0 | −0.29, −0.10 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.23 | −4.5 | −0.33, −0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.10 | −1.6 | −0.22, 0.03 | 0.200 | 0.400 | −0.11 | −1.8 | −0.24, 0.01 | 0.100 | 0.300 |

| GFAP | −0.2 | −5.1 | −0.30, −0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.24 | −4.7 | −0.34, −0.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.16 | −2.9 | −0.27, −0.05 | 0.009 | 0.035 | −0.16 | −2.9 | −0.27, −0.05 | 0.007 | 0.031 |

| Aβ42/40 | 0.0 | 0.5 | −0.07, 0.11 | 0.600 | 0.600 | 0.00 | −0.1 | −0.09, 0.09 | >0.9 | >0.9 | 0.03 | −0.8 | −0.12, 0.05 | 0.500 | 0.700 | 0.03 | −0.7 | −0.12, 0.05 | 0.600 | 0.800 |

| p‐tau181 | −0.2 | −3.1 | −0.25, −0.05 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.11 | −2.1 | −0.21, −0.01 | 0.055 | 0.082 | −0.10 | −1.7 | −0.21, 0.01 | 0.100 | 0.200 | −0.12 | −2.0 | −0.23, 0.00 | 0.062 | 0.200 |

| PLASMA SUM | −0.2 | −4.72 | −0.29, −0.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.21 | −4.07 | −0.31, −0.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.13 | −2.07 | −0.25, −0.01 | 0.063 | 0.200 | −0.15 | −2.33 | −0.27, −0.02 | 0.034 | 0.089 |

| FW | Base (N = 443) | Adj (N = 323) | F‐Adj (N = 318) | F‐Adj‐Dx (N = 318) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | Beta | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | |

| NfL | 0.3 | 5.0 | 0.19, 0.43 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 4.5 | 0.18, 0.47 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 1.5 | −0.03, 0.27 | 0.100 | 0.200 | 0.10 | 1.3 | −0.05, 0.25 | 0.200 | 0.300 |

| GFAP | 0.3 | 5.0 | 0.15, 0.35 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 3.8 | 0.12, 0.37 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 2.5 | 0.04, 0.30 | 0.008 | 0.020 | 0.16 | 2.5 | 0.03, 0.29 | 0.011 | 0.028 |

| Aβ42/40 | −0.1 | −1.6 | −0.15, 0.02 | 0.200 | 0.200 | −0.05 | −1.0 | −0.14, 0.05 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.01 | 0.3 | −0.07, 0.09 | 0.800 | 0.800 | 0.02 | 0.5 | −0.06, 0.10 | 0.700 | 0.700 |

| p‐tau181 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 0.10, 0.30 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 2.6 | 0.04, 0.26 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.02 | 0.4 | −0.10, 0.15 | 0.700 | 0.800 | 0.01 | 0.2 | −0.12, 0.14 | 0.900 | >0.9 |

| PLASMA SUM | 0.29 | 5.74 | 0.19, 0.39 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 4.46 | 0.16, 0.40 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 1.67 | −0.02, 0.26 | 0.100 | 0.200 | 0.10 | 1.38 | −0.04, 0.24 | 0.200 | 0.300 |

Note: Base (unadjusted) and adjusted models associating plasma and neuroimaging‐derived biomarkers are presented. Modest associations were observed between plasma and neuroimaging markers prior to and after adjustment with eGFR and BMI. In fully adjusted models, GFAP remained associated with all imaging biomarkers except gmCBF. Plasma biomarkers and gmCBF were weakly associated in unadjusted models only. p‐tau181, GFAP, and the plasma composite (Plasma Sum) were most strongly associated with Aβ‐PET, and NfL with BVOL before and after adjustment.

Abbreviations: Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI) and covariates (age, sex, race, education, APOE ε4 status, and antihypertensive medication);Aβ, amyloid beta; Base: baseline unadjusted models; BVOL, brain volume (adjusted for intracranial volume); CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; Dx, diagnosis; FA, fraction anisotropy; F‐Adj‐Dx, fully adjusted linear models adding in diagnostic status (Dx: CU, MCI, DEM); FW, free water; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light chain; NODDI, neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging; q, Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate; SUVr, standardized uptake value ratio; WMH, log‐transformed global white matter hyperintensity values.

Bold values represent plasma biomarker coefficient significant at p < 0.05.

3.4. Aβ‐PET positivity status

Plasma biomarkers were significantly associated with greater odds of being Aβ‐PET positive in unadjusted models and in models adjusted for eGFR and BMI (all p < 0.05; Table 4). , GFAP and p‐tau181, but not NfL or Aβ42/40, remained associated with Aβ‐PET positivity status after controlling for additional demographic factors irrespective of clinical diagnosis. When plasma biomarkers were entered simultaneously as predictors in unadjusted models (Table 5), GFAP, Aβ42/40, and p‐tau181 were associated with increased odds of being classified as Aβ‐PET positive, in adjusted models only p‐tau181 remained significantly associated with Aβ‐PET positivity (standardized odds ratios: 2.03 to 5.61, p < = 0.003; Table 5) (model area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC]: Base = 0.866; Adj = 0.890; F‐Adj = 0.914; F‐Adj‐Dx = 0.944; all p < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Independent associations between plasma biomarker levels and Aβ‐PET positivity status.

| Base | Adj | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR 1 | SE 1 | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | N | OR 1 | SE 1 | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | |

| NfL | 140 | 2.46 | 0.23 | 3.98 | 1.61, 3.93 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 81 | 2.24 | 0.32 | 2.5 | 1.23, 4.42 | 0.007 | 0.021 |

| GFAP | 140 | 3.42 | 0.25 | 4.93 | 2.18, 5.82 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 81 | 3.35 | 0.35 | 3.44 | 1.79, 7.18 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Aβ42/40 | 140 | 0.35 | 0.25 | −4.2 | 0.21, 0.55 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 81 | 0.6 | 0.27 | −1.9 | 0.34, 0.98 | 0.042 | 0.130 |

| p‐tau181 | 140 | 3.59 | 0.26 | 4.92 | 2.25, 6.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 81 | 7.69 | 0.47 | 4.33 | 3.33, 21.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR 1 | SE 1 | Z | 95% CI 1 | p | q | N | OR 1 | SE 1 | Z | 95% CI 1 | P | q | |

| NfL | 77 | 1.29 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.52, 3.40 | 0.599 | 0.700 | 77 | 1.37 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.47, 4.25 | 0.599 | 0.700 |

| GFAP | 77 | 4.82 | 0.58 | 2.72 | 1.84, 18.7 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 77 | 6.94 | 0.68 | 2.85 | 2.24, 36.2 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Aβ42/40 | 77 | 0.87 | 0.31 | −0.4 | 0.47, 1.68 | 0.699 | 0.800 | 77 | 0.95 | 0.34 | −0.1 | 0.49, 1.97 | 0.899 | 0.899 |

| p‐tau181 | 77 | 6.62 | 0.59 | 3.22 | 2.42, 24.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 77 | 12.9 | 0.79 | 3.25 | 3.47, 80.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Note: Logistic regression models assessed independent associations between plasma biomarker levels and amyloid PET positivity status before and after adjusting for covariates and comorbid health complications. All continuous predictors were z‐scored prior to analysis.

Abbreviations: Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI); Aβ, amyloid beta; Base, baseline unadjusted models; CI, confidence interval; CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia;Dx, Diagnosis; F‐Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI) and covariates (age, sex, race, education, APOE ε4 status); F‐Adj‐Dx, full adjusted model plus diagnosis; GFAP, glial acid fibrillary protein; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light chain; OR, odds ratio; p‐Tau, phosphorylated tau at Threonine 181; q, Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate; SE, standard error.

Bold value represent plasma biomarker coefficient significant at p < 0.05.

TABLE 5.

Relationship between plasma biomarker levels and Aβ‐PET positivity status.

| Base | Adj | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR1 | SE1 | Z | 95% CI1 | p | q | N | OR1 | SE1 | Z | 95% CI1 | p | q | |

| NfL | 140 | 1.07 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.57, 1.96 | 0.819 | 0.936 | 81 | 1.13 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 0.45, 2.62 | 0.778 | 0.936 |

| GFAP | 140 | 1.97 | 0.31 | 2.2 | 1.11, 3.75 | 0.020 | 0.053 | 81 | 1.59 | 0.42 | 1.12 | 0.74, 3.85 | 0.244 | 0.434 |

| Aβ42/40 | 140 | 0.49 | 0.24 | −2.9 | 0.30, 0.78 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 81 | 0.77 | 0.3 | −0.9 | 0.43, 1.43 | 0.379 | 0.606 |

| p‐tau181 | 140 | 2.03 | 0.27 | 2.61 | 1.26, 3.68 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 81 | 5.2 | 0.51 | 3.23 | 2.10, 15.7 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| F‐Adj | F‐Adj‐Dx | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR1 | SE1 | Z | 95% CI1 | p | q | N | OR1 | SE1 | Z | 95% CI1 | p | q | |

| NfL | 77 | 1.01 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 0.34, 2.65 | 0.988 | 0.988 | 77 | 0.74 | 0.62 | −0.5 | 0.20, 2.28 | 0.626 | 0.911 |

| GFAP | 77 | 1.91 | 0.49 | 1.32 | 0.77, 5.50 | 0.168 | 0.336 | 77 | 2.01 | 0.51 | 1.37 | 0.74, 5.94 | 0.166 | 0.336 |

| Aβ42/40 | 77 | 1.13 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.52, 2.86 | 0.770 | 0.936 | 77 | 1.05 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 0.44, 3.18 | 0.916 | 0.977 |

| p‐tau181 | 77 | 4.7 | 0.55 | 2.8 | 1.82, 16.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 77 | 5.61 | 0.66 | 2.63 | 1.94, 26.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Note: Logistic regression models assessed associations between plasma biomarker levels and amyloid PET positivity status before and after adjusting for covariates and comorbid health complications. Here, all plasma biomarkers were entered simultaneously to predict amyloid PET positivity status. All continuous predictors were z‐scored prior to analysis.

Abbreviations: Aβ, Amyloid‐Beta; Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI); Base, baseline model with all plasma biomarkers as predictors; F‐Adj, linear models adjusted for comorbidities (eGFR, BMI) & covariates (Age, Sex, Race, Education, APOE‐ε4 status); F‐Adj‐Dx., Full adjusted model plus diagnosis; CI, confidence interval; NfL, neurofilament light chain; GFAP, glial acid fibrillary protein; p‐Tau, Phosphorylated Tau at Threonine 181; OR, odds‐ratio; SE, standard error; q, Benjamini‐Hochberg false discovery rate.

3.5. Supplemental exploratory stratification analyses

Marginal group differences were observed when stratifying comorbid health complications (eGFR, BMI) and plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers by sex, race, APOE ε4, and Aβ‐PET positivity status (Table 6; see Table S8 for a full statistical breakdown of results; also see Figure S3). In exploratory post hoc analyses (not shown), we did not observe any effect modification for any of the imaging outcomes assessed when testing for interaction terms between plasma biomarkers and either Dx, race, sex, or APOE ε4 carrier status.

TABLE 6.

Stratification analysis effect‐size summary table.

| Health factors | Plasma biomarkers | Neuroimaging biomarkers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR | BMI | NfL | GFAP | Aβ42/40 | p‐tau181 | Aβ‐PET | BVOL | WMH | FA | FW | |

| Sex | S | S | S | S | |||||||

| Race | S | S | S | S | S | S | |||||

| APOE ε4 | S | S | M | S | |||||||

| Dx | S | M | M | M | M | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Aβ‐POS | S | M | L | M | L | L | M | S | S | ||

Note: Stratification analyses assessed unadjusted group mean differences between males and females (sex), White and Black participants (Race), APOE ε4 carriers versus non‐carriers, participants clinically adjudicated as CU, MCI, or DEM (Dx), and Aβ‐PET‐positive versus negative individuals (Aβ‐POS). Non‐parametric Kruskal–Wallis effect size estimates are presented for models with significant group differences after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate. Magnitude of effect sizes is based on established norms (small: 0.01 to 0.059; moderate: 0.06 to 0.139; large ≥ 0.14).

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; BMI, body mass index; BVOL, total brain volume; CU, cognitively unimpaired; DEM, dementia; Dx, diagnosis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FA, fractional anisotropy; FW, free water; GFAP, glial acid fibrillary protein; L, large effect size; M, moderate effect size; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NfL, neurofilament light chain; p‐Tau, phosphorylated tau at threonine 181; S, small effect size; WMH, white matter hyperintensities.

4. DISCUSSION

While CSF remains the gold standard biofluid for ADRD biomarkers, plasma biomarkers are a feasible and low‐cost means of detecting, tracking, and monitoring disease progression. At present, there is a critical need to understand better how clinical, physiological, and pathological factors alter levels of plasma biomarkers 1 , 4 , 33 and the extent to which such factors may impact associations with well‐established (imaging) biomarkers of AD/ADRD in more diverse cohorts. We systematically assessed the extent to which health‐related risk factors and comorbidities may alter or weaken specific relationships between plasma and imaging biomarkers. Plasma biomarker levels significantly differed between clinically adjudicated groups (DEM > MCI > CU), were altered in Aβ‐PET‐positive individuals, and were overall modestly associated with poorer brain health (eg, lower total brain volume, higher amyloid deposition) in adjusted and unadjusted linear models. Plasma biomarkers were most associated with greater amyloid deposition (Aβ‐PET) and lower total volume (BVOL) and, to a lesser extent, with neurodegeneration and pathology specific to white matter. Associations between plasma and imaging biomarkers were independent of eGFR and BMI.

4.1. Comorbidities and risk factors

As observed in previous studies, and replicated here, levels of plasma biomarkers increased with age 34 , 35 and were altered by BMI and kidney dysfunction. 5 , 6 , 7 In the study by Mielke and colleagues (2022), however, both p‐tau181 and p‐tau217 only increased with age among Aβ‐PET‐positive but not negative individuals. 7 Here, we found that this effect was specific to measures of amyloid deposition (eg, p‐tau181 and Aβ42/40) but not NfL or GFAP (Figure S1). Age was also not a significant factor over and above APOE ε4 status in models assessing the relationship between plasma biomarkers and Aβ‐PET deposition, consistent with prior work documenting age‐independent effects of APOE on amyloid deposition. 36 Although comorbidities or common risk factors of AD/ADRD may alter levels of circulating plasma biomarkers in older adults, previous research suggested that they have modest effects in (linear) statistical models predicting CSF‐derived measures of neuropathology, cognitive impairment, and diagnosis of MCI or dementia. 5 , 37 In the current study, we also found a limited impact of eGFR and BMI on linear associations between plasma AD/ADRD biomarkers and neuroimaging measures. Of note, eGFR and BMI were not associated with one another in the whole sample or when stratified by clinical diagnosis. Critically, as noted earlier (also see Methods), no participants in our study had CKD (eGFR < 30) at baseline, so were unable to assess further the impact that chronically abnormal levels of kidney functioning have on biomarker associations. The combined influence of eGFR and BMI most influenced associations with Aβ42/40 and least impacted associations with Aβ‐PET in the current study. Interestingly, the inverse effects of BMI, as noted by Syrjanen and colleagues, may be attributed to impaired insulin signaling and glucose metabolism. 6 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 It should be noted that the presence of CKD remains of critical importance and can help prevent incorrect etiological diagnoses and refinement of clinical cutpoints as clinical decisions come to rely more heavily on blood‐based (eg, plasma) biomarkers. We focused primarily on the impact of kidney functioning and BMI as such factors are more directly linked to clearance of plasma proteins than other potential comorbidities. The Wake Forest ADRC cohort provides an array of data on cardiometabolic and other risk factors that may underlie an increased risk of dementia in a subset of participants. Thus, future work can help disentangle complex interactions between health‐related and other risk factors, as well as explicitly model rather than covary for co‐pathologies and medication use as more data become available.

4.2. Stratified analyses

eGFR differed only by race, where estimates of eGFR were lower in White compared to Black/African American participants. We further observed marginal but significant group differences comparing biomarker levels between males and females and when stratifying by race or APOE ε4 status. Specifically, females exhibited slight elevations in GFAP, and the plasma composite as compared to males, while NfL and p‐tau181 were elevated (Aβ42/40 reduced) in White compared to Black/African American participants. BMI–plasma biomarker associations were exclusive to the CU cohort. In adjusted models, BMI‐attenuated plasma–imaging biomarker associations for white but not gray matter pathology or amyloid deposition. Inconsistent findings concerning relationships between Aβ40 and Aβ42 (or other plasma biomarkers) with imaging biomarkers may further highlight the importance of examining markers within representative cohorts at different disease stages. How health‐related risk factors and comorbidities impact overall health and the degree to which plasma and imaging biomarkers indicate overall risk of cognitive decline and dementia may be person‐specific. In future work, we plan to utilize predictive modeling strategies to better account for high‐dimensional interactions between both well‐established and nascent risk factors captured in our cohort.

The Wake Forest ADRC cohort is relatively more racially diverse than most of the previously published populations used to analyze plasma biomarkers and provides an array of data on cardiometabolic and other risk factors that may underlie an increased risk of dementia. Importantly, however, the final sample analyzed here remains ∼75% White (∼75% female) and ∼95% White concerning PET imaging, where the sample size of participants is reduced compared to those with MRI measures. Lower rates of Aβ‐PET positivity and reduced estimates of Aβ‐PET deposition and plasma Aβ have been reported on average in Black/African Americans, even in those who carry the APOE ε4 allele. 42 , 43 We are committed to enhancing representation of underrepresented groups in our cohort and emphasize the continued need for increased representation across ADRCs to ensure proper inference when drawing conclusions about the diagnostic and prognostic value of biomarkers in the population.

Amyloid PET centiloid (CL) values were also calculated in the Wake Forest ADRC cohort following established guidelines. 44 Initial estimates suggested our SUVr cutoff of 1.21 was equivalent to ∼18.8 CL. Continued exploration of biomarker outpoints in the context of both comorbidities and demographic characteristics is warranted. Cardiovascular risk factors implicated in AD may differentially impact the deposition of Aβ within a particular racial/ethnic group, including Black/African Americans. 45 , 46 In our cohort, plasma and imaging biomarker levels were lower, on average, in Black/African Americans compared to White participants. Caution against overinterpretation of stratified analyses is warranted given the characteristics of our sample, particularly the limited number of non‐White participants, considerable overlap in biomarker levels, and observed small effect sizes. Our intent was to provide a detailed examination of plasma–imaging associations given the characteristics of our cohort. Critically, high‐dimensional interactions among competing risk factors as assessed here (eg, age, sex, race, ethnicity, APOE) may modify associations between plasma and imaging biomarkers in a stage‐specific manner and, thus, require longitudinal assessment. 47 Likewise, although not unique to our ADRC cohort, 48 the greater number of female than male participants in our cohort may bias future analyses assessing sex differences concerning. Recruitment is ongoing, and efforts to increase representation, particularly in our imaging cohort, are under way.

The Wake Forest ADRC cohort primarily includes participants with dementia with typical amnestic symptoms, etiologically due to AD; as such, this study is underpowered to examine differential effects by dementia subtypes. Regardless, combinations of plasma biomarkers and imaging biomarkers may better distinguish between biological subtypes of dementia in diverse cohorts. Here, we found that a simple sum composite of plasma biomarkers (PLASMA SUM) slightly improved associations with all imaging biomarkers assessed, except Aβ‐PET deposition. Plasma biomarkers were moderately correlated with one another, and we observed small but significant differences when stratifying the sample by sex, race, APOE ε4 status, Aβ‐PET positivity, or Dx. Thus, combining biomarkers in this fashion may result in a loss of critical information and not generalize well across cohorts. In terms of prediction, the inclusion of multiple plasma biomarkers has been shown to (1) outperform plasma biomarkers when assessed independently and (2) improve 4‐year prediction of conversion of MCI to dementia and prediction of amyloid and tau neuropathological stages. 49 Regardless, plasma biomarkers may be best suited to serve as screening tools, 1 , 3 , 5 , 50 helping to identify at‐risk individuals who should undergo additional testing (eg, PET and CSF). Further consideration of inflammation or vascular related blood‐based biomarkers, such as interleukin 6, C‐reactive protein, or placental growth factor, may provide additional insights into mechanisms that contribute to cognitive impairment and dementia seen in mid versus late life 51 , 52 , 53 and help distinguish subtypes of dementia. 54 Future studies should attempt to understand how plasma biomarkers provide added sensitivity over and above other established risk factors and biomarkers in elucidating pathways to dementia.

5. CONCLUSION

Plasma biomarker levels significantly differed across diagnostic groups (DEM > MCI > CU), were altered in Aβ‐PET‐positive individuals, and, overall, moderately associated with poorer brain health in adjusted and unadjusted linear models. Plasma biomarkers were most associated with higher amyloid deposition (Aβ‐PET) and lower total brain volume (BVOL); associations with markers of white matter‐specific neurodegeneration and pathology were limited. Overall, the addition of health‐related risk factors did not alter associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers. Except for GFAP and, to an extent, p‐tau181, associations between plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers were differentially impacted by covariate adjustment before and after stratifying by clinical diagnosis. The combination of plasma biomarkers and imaging biomarkers may help better establish biomarker‐specific cutoffs that are both clinically useful and that generalize across studies and cohorts. Extending this work, incorporating additional analytes including p‐tau217, we aim to establish a range of clinically relevant cutoffs (eg, thresholds) for plasma biomarkers in reference to established biomarkers, demographics, and diagnostic information in the context of demographic and health‐related information.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships, which may be considered as potential competing interests: Marc Rudolph, Courtney Sutphen, Thomas Register, Christopher Whitlow, Kiran Solingapuram Sai, Timothy Hughes, and Kristen Russ have no conflicts of interest to disclose. James R. Bateman and Samuel N. Lockhart receive funding from the NIH and Alzheimer's Association. Dage is an inventor on patents or patent applications of Eli Lilly and Company relating to the assays, methods, reagents, and/or compositions of matter for p‐tau assays. Dage has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Eisai, Abbvie, Genotix Biotechnologies Inc., Gates Ventures, Karuna Therapeutics, AlzPath Inc., and Cognito Therapeutics, Inc., and received research support from ADx Neurosciences, Fujirebio, AlzPath Inc., Roche Diagnostics, and Eli Lilly and Company in the past 2 years. Dage has received speaker fees from Eli Lilly and Company. Dage is a founder and advisor for Monument Biosciences. Dage has stock or stock options in Eli Lilly and Company, Genotix Biotechnologies, AlzPath Inc., and Monument Biosciences. Michelle Mielke consults for or serves on advisory boards for Biogen, Eisai, Lilly, Merck, Roche, and Siemens Healthineers. Suzanne Craft reports disclosures for vTv Therapeutics, T3D Therapeutics, Cyclerion Inc., and Cognito Inc. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants and/or their legally authorized representatives.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine's Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (P30AG049638, P30AG072947, R01AG054069, R01AG058969, and T32AG033534), which is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Additional support was provided by the Department of Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine and Center for Healthy Aging and Alzheimer's Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine. Data from the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD), which receives government support under a cooperative agreement grant (U24 AG21886) awarded by the NIA, were used in this study. It would not have been possible without the commitment and support of our valued ADRC staff and study participants. This study was supported by the following funding sources: Rudolph reports funding for this work from National Institutes of Health (NIH) P30AG072947 and T32AG033534. Sutphen reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG049638 and P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution, including T32AG033534. Register reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG049638 and P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution. Whitlow reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution. Solingapuram Sai reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution. Hughes reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution. Bateman reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947, other NIH grants, and funding from ASPECT 20‐AVP‐786‐306 to the institution. Dage reports funding for this work from U24AG021886 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution, including U01AG057195, P30AG072976, RD005665, RD006263, U54AG054345, U19AG074879, R01AG072474, U54AG065181, R01AG068193, U24AG082930, R01AG077202, U01AG082350, and from the Michael J. Fox Foundation MJFF‐023365. Russ reports funding for this work from U24AG021886 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution. Mielke reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution. Craft reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants. Lockhart reports funding for this work from NIH P30AG072947 and additional funding from other NIH grants to the institution.

Rudolph MD, Sutphen CL, Register TC, et al. Associations among plasma, MRI, and amyloid PET biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias and the impact of health‐related comorbidities in a community‐dwelling cohort. Alzheimer's Dement. 2024;20:4159–4173. 10.1002/alz.13835

REFERENCES

- 1. Alcolea D, Delaby C, Muñoz L, et al. Use of plasma biomarkers for AT(N) classification of neurodegenerative dementias. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(11):1206‐1214. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-326603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(3):131‐144. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smirnov DS, Ashton NJ, Blennow K, et al. Plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease in relation to neuropathology and cognitive change. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;143(4):487‐503. doi: 10.1007/s00401-022-02408-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teunissen CE, Verberk IMW, Thijssen EH, et al. Blood‐based biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: towards clinical implementation. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(1):66‐77. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00361-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pichet Binette A, Janelidze S, Cullen N, et al. Confounding factors of Alzheimer's disease plasma biomarkers and their impact on clinical performance. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(4):1403‐1414. doi: 10.1002/alz.12787. Published online 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Syrjanen JA, Campbell MR, Algeciras‐Schimnich A, et al. Associations of amyloid and neurodegeneration plasma biomarkers with comorbidities. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(6):1128‐1140. doi: 10.1002/alz.12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mielke MM, Dage JL, Frank RD, et al. Performance of plasma phosphorylated tau 181 and 217 in the community. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1398‐1405. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01822-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Bryant SE, Xiao G, Edwards M, et al. Biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease among Mexican Americans. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(4):841. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coffin C, Suerken CK, Bateman JR, et al. Vascular and microstructural markers of cognitive pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;14(1):e12332. doi: 10.1002/DAD2.12332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yuan A, Nixon RA. Neurofilament proteins as biomarkers to monitor neurological diseases and the efficacy of therapies. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:689938. doi: 10.3389/FNINS.2021.689938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abdelhak A, Foschi M, Abu‐Rumeileh S, et al. Blood GFAP as an emerging biomarker in brain and spinal cord disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18(3):158‐172. doi: 10.1038/s41582-021-00616-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Czeiter E, Amrein K, Gravesteijn BY, et al. Blood biomarkers on admission in acute traumatic brain injury: relations to severity, CT findings and care path in the CENTER‐TBI study. EBioMedicine. 2020;56:102785. doi: 10.1016/J.EBIOM.2020.102785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Fluid biomarkers for mild traumatic brain injury and related conditions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(10):563‐574. doi: 10.1038/NRNEUROL.2016.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Newcombe VFJ, Ashton NJ, Posti JP, et al. Post‐acute blood biomarkers and disease progression in traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2022;145(6):2064‐2076. doi: 10.1093/BRAIN/AWAC126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270. doi: 10.1016/J.JALZ.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263. doi: 10.1016/J.JALZ.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249‐258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0B013E318142774E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes TM, Lockhart SN, Suerken CK, et al. Hypertensive aspects of cardiometabolic disorders are associated with lower brain microstructure, perfusion, and cognition. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;90(4):1589. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmidt P, Gaser C, Arsic M, et al. An automated tool for detection of FLAIR‐hyperintense white‐matter lesions in multiple Sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):3774‐3783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raz N, Yang Y, Dahle CL, Land S. Volume of white matter hyperintensities in healthy adults: contribution of age, vascular risk factors, and inflammation‐related genetic variants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2012;1822(3):361‐369. doi: 10.1016/J.BBADIS.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oishi K, Faria A, Jiang H, et al. Atlas‐based whole brain white matter analysis using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping: application to normal elderly and Alzheimer's disease participants. Neuroimage. 2009;46(2):486. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lockhart SN, Schaich CL, Craft S, et al. Associations among vascular risk factors, neuroimaging biomarkers, and cognition: preliminary analyses from the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(4):551‐560. doi: 10.1002/ALZ.12429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh Compound‐B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306‐319. doi: 10.1002/ANA.20009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mormino EC, Brandel MG, Madison CM, et al. Not quite PIB‐positive, not quite PIB‐negative: slight PIB elevations in elderly normal control subjects are biologically relevant. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):1152. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2011.07.098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Villeneuve S, Rabinovici GD, Cohn‐Sheehy BI, et al. Existing Pittsburgh Compound‐B positron emission tomography thresholds are too high: statistical and pathological evaluation. Brain. 2015;138(7):2020. doi: 10.1093/BRAIN/AWV112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pérez‐Grijalba V, Romero J, Pesini P, et al. Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio detects early stages of Alzheimer's disease and correlates with CSF and neuroimaging biomarkers in the AB255 study. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019;6(1):34‐41. doi: 10.14283/JPAD.2018.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fandos N, Pérez‐Grijalba V, Pesini P, et al. Plasma amyloid β 42/40 ratios as biomarkers for amyloid β cerebral deposition in cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;8:179. doi: 10.1016/J.DADM.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schindler SE, Bateman RJ. Combining blood‐based biomarkers to predict risk for Alzheimer's disease dementia. Nature Aging. 2021;1(1):26‐28. doi: 10.1038/s43587-020-00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kassambra A. Pipe‐Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests [R package rstatix version 0.6.0]. 2020. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:230685253

- 30. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Statist Soc Ser C. 1995;57(1):289‐300. doi: 10.2307/2346101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Delanaye P, Mariat C. The applicability of eGFR equations to different populations. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(9):513‐522. doi: 10.1038/NRNEPH.2013.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stevens LA, Levey AS. Measured GFR as a confirmatory test for estimated GFR. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(11):2305‐2313. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009020171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hansson O, Edelmayer RM, Boxer AL, et al. The Alzheimer's association appropriate use recommendations for blood biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(12):2669‐2686. doi: 10.1002/alz.12756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yakoub Y, Ashton NJ, Strikwerda‐Brown C, et al. Longitudinal blood biomarker trajectories in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(12):5620‐5631. doi: 10.1002/ALZ.13318. Published online 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gu Y, Honig LS, Kang MS, et al. Risk of Alzheimer's disease is associated with longitudinal changes in plasma biomarkers in the multiethnic washington heights, inwood Columbia aging project cohort. medRxiv. 2023. Published online August 16, 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.08.11.23293967 [DOI]

- 36. Swaminathan S, Risacher SL, Yoder KK, et al. Association of plasma and cortical amyloid beta is modulated by APOE ε4 status. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(1):e9‐e18. doi: 10.1016/J.JALZ.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tang R, Panizzon MS, Elman JA, et al. Association of neurofilament light chain with renal function: mechanisms and clinical implications. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01134-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Craft S, Claxton A, Baker LD, et al. Effects of regular and long‐acting insulin on cognition and Alzheimer's disease biomarkers: a pilot clinical trial. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017;57(4):1325‐1334. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benedict C, Grillo CA. Insulin resistance as a therapeutic target in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a state‐of‐the‐art review. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:215. doi: 10.3389/FNINS.2018.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bharadwaj P, Wijesekara N, Liyanapathirana M, et al. The link between type 2 diabetes and neurodegeneration: roles for Amyloid‐β, Amylin, and tau Proteins. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017;59(2):421‐432. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gonçalves RA, Wijesekara N, Fraser PE, De Felice FG. The link between tau and insulin signaling implications for Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:17. doi: 10.3389/FNCEL.2019.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hall JR, Petersen M, Johnson L, O'Bryant SE. Characterizing plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer's in a diverse community‐based cohort: a cross‐sectional study of the HAB‐HD cohort. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1003. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.871947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schindler SE, Karikari TK, Ashton NJ, et al. Effect of race on prediction of brain amyloidosis by plasma Aβ42/Aβ40, phosphorylated tau, and neurofilament light. Neurology. 2022;99(3):E245‐E257. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, et al. The Centiloid Project: standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(1):1‐15.e1‐4. doi: 10.1016/J.JALZ.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Alzheimer's disease in African Americans: risk factors and challenges for the future. Health Aff. 2014;33(4):580‐586. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deniz K, Ho CCG, Malphrus KG, et al. Plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease in African Americans. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2021;79(1):323‐334. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Benedet AL, Leuzy A, Pascoal TA, et al. Stage‐specific links between plasma neurofilament light and imaging biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2020;143(12):3793. doi: 10.1093/BRAIN/AWAA342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gauthreaux K, Kukull WA, Nelson KB, et al. Different cohort, disparate results: selection bias is a key factor in autopsy cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20(1):266‐277. doi: 10.1002/ALZ.13422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Algeciras‐Schimnich A, et al. Predicting amyloid PET and tau PET stages with plasma biomarkers. Brain. 2023;146(5):2029‐2044. doi: 10.1093/BRAIN/AWAD042. Published online February 15, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Toledo JB, Vanderstichele H, Figurski M, et al. Factors affecting Aβ plasma levels and their utility as biomarkers in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(4):401. doi: 10.1007/S00401-011-0861-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cipollini V, Troili F, Giubilei F. Emerging biomarkers in vascular cognitive impairment and dementia: from pathophysiological pathways to clinical application. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11):2812. doi: 10.3390/IJMS20112812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Erhardt EB, Adair JC, Knoefel JE, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers aid in diagnosis of dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:717344. doi: 10.3389/FNAGI.2021.717344/FULL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Quillen D, Hughes TM, Craft S, et al. Levels of Soluble interleukin 6 receptor and Asp358Ala are associated with cognitive performance and Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2023;10(3):e200095. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hinman JD, Elahi F, Chong D, et al. Placental growth factor as a sensitive biomarker for vascular cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(8):3519‐3527. doi: 10.1002/ALZ.12974. Published online 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information