Underpinning contemporary theories of quality improvement is the axiom that poor individual performance usually reflects wider “system failure” or the absence of an organisation-wide system of quality assurance.1 In healthcare organisations, critical incidents can lead to death, disability, or permanent discomfort. This, together with clinicians' tendency to protect their individual autonomy and reputation, can promote a culture of blame and secrecy that inhibits the organisational learning necessary to prevent such incidents in future.

LIANE PAYNE

Introducing clinical governance to primary care, the government stated that it “must be seen as a systematic approach to quality assurance and improvement within a health organisation . . . Above all clinical governance is about changing organisational culture . . . away from a culture of blame to one of learning so that quality infuses all aspects of the organisation's work.”2 This paper seeks to identify the contribution of organisational development to the effective establishment of clinical governance.

Summary points

Organisational development is a field of applied behavioural science focused on managing change and improving effectiveness in organisations

Four aspects of organisational development are particularly important: cultural change, the development of technical skills, structural change, and the development of effective leadership

Developing the necessary culture for clinical governance will be difficult given the variability of general practices and practitioners

An agenda of control and risk management could jeopardise the inventiveness and innovation that secures continuous improvement

What is the organisation?

The idea of organisation-wide quality improvement poses challenges in a primary care setting. Much care is still provided by relatively isolated professionals based in small practices, which are not typically thought of as “organisations.” Newly formed primary care groups and trusts are easier to conceptualise as organisations, but many have yet to develop the sense of cohesion and “organisational belonging” among member clinicians that will be required for effective clinical governance.3

Currently, the primary care group is a subcommittee of the health authority, whose chief executive is ultimately accountable for the development of clinical governance in primary care. However, primary care groups are seen as the focal organisation for the practical implementation of clinical governance, and responsibility for this work lies with the primary care group chairperson as “responsible officer.” Responsibility for clinical governance and the role of the lead clinicians responsible for clinical governance will transfer to primary care trusts as they develop.

Crossnational studies have found that differences in healthcare systems have important consequences for quality assurance in general practice.4 Similarly, the different models of primary care trust already emerging are likely to generate different models of clinical governance. Whatever the shape of future primary care organisations, practices remain the basic building block for the time being. Recognising the critical importance of the relationship between these two organisations, most primary care groups are encouraging the identification of practice leads.5

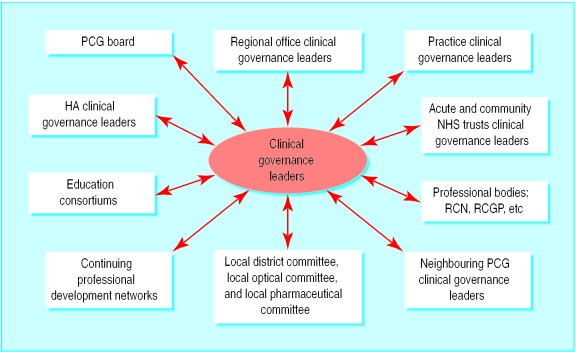

The challenge for individual primary care clinicians participating in clinical governance is to balance an appropriate degree of clinical autonomy and professional self determination with a sense of collective responsibility for quality improvement in the new organisation to which they are now connected. Those leading the implementation of clinical governance will have to engage local clinicians in quality improvement work in a way that is non-threatening and encourages a commitment to organisational standards and values. They will also have to develop links with a wide range of external organisations (box) with whom joint work will be an important ingredient of success.

Critical relationships for clinical governance

Clinical governance leaders have reciprocal relationships with each other and a wide range of external organisations

Clinical governance leaders within:

Practices

Neighbouring primary care groups

Acute and community NHS trusts

Regional office

Health authority

Professional bodies:

Royal College of Nursing, Royal College of General Practitioners, etc

Local district committee, local optical committee, local pharmaceutical committee

Continuing professional development networks

Education consortiums

What is organisational development?

Organisational development is a field of applied behavioural science that seeks to develop the principles and practice of managing change and improving effectiveness in organisations.6–8 Establishing clinical governance will involve introducing complex change into the turbulent environment of the primary care group and its constituent practices. Many other initiatives, such as health action zones and personal medical service pilots, are occurring at the same time. This context is far more complex than that of the single organisations that are the focus of most organisational development literature.

American research on quality improvement in health care shows that three areas of organisational development will be particularly important.9 Firstly, cultural change ensures that the underlying beliefs and values of the organisation support the open, constructive reflection required for effective clinical governance. Secondly, “technical” development ensures that people have the skills to undertake such work, and, thirdly, structural development of committees and systems is necessary to coordinate and monitor quality improvement work.

In addition, effective organisational development requires determined leadership. Those responsible for the development of clinical governance will need a clear understanding of what is being introduced and why. Many questions remain about how clinical governance will fit with the wider work of the organisation. How, for example, will clinical governance relate to corporate governance? Is clinical governance expected to assure minimum standards of clinical practice, or is it expected to promote continuous improvement and innovation? Is clinical governance a total quality assurance system or only part of one? Such uncertainty may limit the sense of conviction and urgency required for effective management of change.10

Organisational development for clinical governance

To date, many primary care groups have focused on developing the organisational structures required for clinical governance (see, for example, Ayres et al11). Thus, they have identified clinical governance leaders at board and practice level and have established subcommittees of the board relating to issues such as education and training, risk management, and audit. They have established lines of accountability to the health authority and in some cases to patients by involving lay members in clinical governance committees.

Given the complex multiprofessional and intersectoral nature of clinical governance, of equal importance is work to establish trust, good communication, and good relationships between all members of the primary care group. Practice visits offer one way to do this, and many clinical governance leads are undertaking such visits. Another approach encourages visits by small groups of local clinicians—not necessarily those leading clinical governance work—to each other's practices. By combining a review of current quality improvement work, discussion of problems, and identification of priorities for future work, such visits can promote peer learning as well as peer review and start to build the relationships necessary for clinical governance.

American studies of doctors' participation in quality improvement work have highlighted the importance of strong medical leadership.9,12 Hospital doctors were more likely to participate in work led by a respected clinician on clinical problems that were perceived as important and for which data were available to monitor practice. Whether such findings can be generalised to a UK primary care setting is questionable, but they raise important questions about the role of clinical leadership in galvanising participation in clinical governance.

Who is leading and managing change and organisational development?

Initially, for many primary care groups, clinical governance was seen as roughly synonymous with audit and clinical effectiveness. In many cases, doctors and nurses with a history of involvement in audit or postgraduate education were assumed to be technically competent and were appointed as leads. However, both large business corporations and the NHS have lost millions of pounds because they saw the establishment of, for example, new information management and technology systems as a purely technical task. Political awareness and the ability to work with colleagues with diverse values and competencies is a prerequisite for anyone promoting change. Clinical governance leads need to know when and how to “sell” the changes in behaviour that are required, and they need to use terms that will appeal to the ethos of the health professional, the small business person, and the primary healthcare team.

In many primary care groups, general practitioners and nurses share the clinical governance leadership role. In our experience, primary care groups differ considerably in the degree to which managers—at the levels of the practice, primary care group, and health authority—are engaged in the implementation process. When most clinicians take up clinical governance roles in addition to their “day jobs,” it is important that they do not duplicate effort on managerial and administrative tasks. Leading change and managing change are different activities requiring different competencies.10

What resources are necessary and available to secure the changes?

Those leading clinical governance need to ensure that the appropriate resources are available. Their capacity to articulate the what, why, and how of the task will often determine their capacity to wrest resources from the system. Their baseline assessments will have identified existing resources, especially human resources, that can be mobilised in support of clinical governance. The box lists some of the organisations housing relevant skills. The formation of informal collaborative relationships (“knowing someone who does”) will have as much to offer clinical governance leads at practice, trust, or primary care group level as will new, sometimes cumbersome, committee structures.

Links among clinical governance structures in community trusts are developing swiftly, particularly among those planning an early transition to primary care trust status, but links with the acute sector are less visible. Levels of support from other agencies such as public health departments, academic bodies, or education networks vary considerably. Furthermore, few clinical governance leads have dedicated input from information or finance managers.13

Practice managers have so far been marginal to the establishment of many primary care groups and are an untapped resource. In recent years they have shifted the previously rigid boundary between clinical and organisational business within the practice.14 Many now possess an awareness of both policy developments and clinical issues that was unheard of 10 years ago. They have also been effective in organisation development in their practices.

A further critical resource in developing an effective system of clinical governance in primary care is the records systems used by each practice and primary care team. In most practices, continuity of care depends on the quality of the patient record and its management. The record has a central role in risk management, audit, and teamwork—yet how many practices have a clause in the partnership or practice agreement which requires partners to observe defined standards of record keeping?15

Money is also required to fund the time of clinicians who are engaged in leading change, and in supporting their learning for the benefit of the wider system. The Audit Commission found that the amount that primary care groups planned to spend on clinical governance this year ranged from £5000 to £128 000, averaging £1667 per practice.5

Because of the emotionally charged climate in which clinical governance is being established and its centrality to the “modernisation agenda,” those who are leading change and development are vulnerable.8 They occupy the boundary between clinical and managerial, professional, and organisational territories. When they are dealing with colleagues who remain independent contractors, the nature of their authority remains unclear. This forces them back on their own skills in forming motivational relationships, with consequent need for support. That support can be provided through conferences, workshops, and facilitated learning groups provided locally or commissioned from external agencies.

Learning organisations

Clinical governance is about promoting continuous improvement as well as establishing baseline standards. It must in part be an emergent process that allows for individual, group, and organisational inventiveness and for leadership to come from anywhere in the organisation or system. The wider organisational challenge is then to be able to convert an invention in one part of the system into innovation throughout it.16

Learning organisations do this through developing the capacity for dialogue, a conversation in which a group “thinks together,” allowing itself to discover insights that might not be accessible to its members thinking individually.17 Dialogue in organisations or human systems is easier where relationships based on shared meaning and purpose already exist, but it is also a means of creating and developing these. The increasing plurality of primary care organisations, with attendant variety in their approaches to clinical governance, should provide a rich source of comparative research in future.

Conclusion

The government has specified the first steps towards clinical governance, but this will not guarantee the culture change that was its declared aim. In the light of high profile system failures in Bristol and elsewhere, the government is understandably concerned to reassure the public. But if clinical governance is driven solely by an agenda of control and risk management, the result could be compliance rather than commitment. The price will be the loss of that inventiveness and innovation that secures a culture of continuous improvement.

Figure.

Existing resources for clinical governance

This is the third in a series of five articles

Footnotes

Series editor: Rebecca Rosen

References

- 1.Berwick DM. Continuous improvement as an ideal in health care. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:53–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS Executive. Clinical governance: in the new NHS. London: NHSE; 1999. . (HSC 1999/065.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhalgh T. Change and the team: group relations theory. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:452–453. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grol R, Baker R, Wensing M, Jacobs A. Quality assurance in general practice: the state of the art in Europe. Fam Pract. 1994;11:460–467. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audit Commission. The PCG agenda: early progress of PCGs in ‘The New NHS’. London: Audit Commission; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckhard R, Pritchard W. Changing the essence: the art of creating and leading fundamental change in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schein E. Organizational culture and leadership: a dynamic view. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan D, Boddy D. The expertise of the change agent: public performance and backstage activity. London: Prentice Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortell S. Physician involvement in quality improvement. In: Blumental D, Scheck A, editors. Improving Clinical Practice. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotter JP. Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayres IL, Cooling R, Maughan H. Clinical governance in primary care groups. Public Health Med. 1999;2:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloomenthal D, Edwards J. Involving clinicians in TQM. In: Blumental D, Scheck A, editors. Improving clinical practice. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward J, Rosen R, Dewar S. Thin on the ground. Health Services J. 1999;Aug 26:26–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huntington J. The people's champion? In: Meads G, Huntington J, Key P, Mumford P, Brown E, Evans K, editors. The unsupported middle. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical; 1997. pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh GN. Efficient care in general practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huntington J. From invention to innovation. In: Meads G, editor. Future options for general practice. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical; 1996. pp. 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt J, Gordon P, Plamping D. Working whole systems: putting theory into practice in organisations. London: King's Fund; 1999. [Google Scholar]