Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the striatum, predominantly associated with motor symptoms. However, non-motor deficits, particularly sensory symptoms, often precede motor manifestations, offering a potential early diagnostic window. The impact of non-motor deficits on sensation behavior and the underlying mechanisms remains poorly understood. In this study, we examined changes in tactile sensation within a Parkinsonian state by employing a mouse model of PD induced by 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) to deplete striatal dopamine (DA). Leveraging the conserved mouse whisker system as a model for tactile-sensory stimulation, we conducted psychophysical experiments to assess sensory-driven behavioral performance during a tactile detection task in both the healthy and Parkinson-like states. Our findings reveal that DA depletion induces pronounced alterations in tactile sensation behavior, extending beyond expected motor impairments. We observed diverse behavioral deficits, spanning detection performance, task engagement, and reward accumulation, among lesioned individuals. While subjects with extreme DA depletion consistently showed severe sensory behavioral deficits, others with substantial DA depletion displayed minimal changes in sensory behavior performance. Moreover, some exhibited moderate degradation of behavioral performance, likely stemming from sensory signaling loss rather than motor impairment. The implementation of a sensory detection task is a promising approach to quantify the extent of impairments associated with DA depletion in the animal model. This facilitates the exploration of early non-motor deficits in PD, emphasizing the importance of incorporating sensory assessments in understanding the diverse spectrum of PD symptoms.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, affecting approximately 1 million individuals in the United States annually, with 90,000 new diagnoses reported each year. Diagnosis is based on identifying common motor symptoms such as tremor, bradykinesia (slowed movement), and muscular rigidity. However, PD patients also experience non-motor impairments, including alterations in olfactory, auditory, tactile, nociceptive, thermal, and proprioceptive perception (Oppo et al. 2020; Jafari, Kolb, and Mohajerani 2020; Kesayan et al. 2015; José Luvizutto et al. 2020; Brim and Struhal 2021). Notably, these non-motor symptoms, often referred to collectively as sensory symptoms, precede the manifestation of motor symptoms by two or more years (Pont-Sunyer et al. 2015), offering a potential window for early diagnostic methods.

In the realm of PD research, animal models have become instrumental in understanding the cellular and circuit mechanisms underlying both motor and non-motor deficits, as well as in the development of therapeutic strategies. The 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) rodent model, involving the injection of the neurotoxin 6-OHDA into the medial forebrain bundle, is a widely used model that induces dopamine (DA) depletion in the striatum, mimicking Parkinson-like symptoms. Originally designed to study motor deficits (Brooks and Dunnett 2009; Francardo et al. 2011; Lundblad et al. 2004), this model has been extended to investigate non-motor deficits in sensory circuits (Ketzef et al. 2017; Reig and Silberberg 2014). However, questions persist regarding how animals behave and interact with their sensory environment, specifically how the perception of sensory stimuli and behavioral response are altered in the DA-depleted state.

Here, we investigate the behavioral aspects of mice trained on a sensory-based detection task in both healthy and Parkinson-like states induced by 6-OHDA lesioning. Leveraging the rodent whisker system for tactile-sensory stimulation, we anticipate reduced task performance in the Parkinson-like state. In addition to the standard behavioral readout of motor impairments, we designed a psychophysical experiment to systematically evaluate task performance in both states. As a complement to conventional measures (Aeed et al. 2021; Branchi et al. 2008), here we highlight the sensory dimension of the task in behaving animals. We hypothesized that a detailed analysis of behavioral readouts and lesion level assessment would reveal specific alterations in sensory processing and subsequent behavioral responses in the DA-depleted state.

Our findings unveil a spectrum of deficits following DA depletion, encompassing rotational asymmetry, weight loss, and varying degrees of altered tactile sensation evident in our behavioral detection task. Despite observing substantial DA depletion in the majority of mice, those displaying severe sensory behavioral deficits consistently exhibited pronounced impairments across all measures. However, some mice with substantial DA depletion, rotational bias, and weight loss displayed only minor sensory behavioral deficits. Others strikingly demonstrated diminished sensory behavioral performance without evident motor function loss, suggesting the emergence of a sensory deficit. Taken together, these results highlight the complex interactions between these factors and underscore the importance of developing a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of DA depletion across sensory, motor, and cognitive functions.

Methods

Experimental model and subject details

All experiments and surgical procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Georgia Institute of Technology Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to guidelines established by the NIH. Subjects were 12 male mice (C57/BL/6J, Jackson Laboratories), aged 16–20 weeks at the age of experimentation. Only males were used in this study because the incidence rate of PD is 1.5 times higher in men than in women (Wooten 2004). Animals were housed together in pairs of two per cage (following surgical recovery when applicable) and housed in an inverted light cycle (light: 7pm-7am: dark: 7am-7pm) to ensure experiments occurred during animals’ wakeful periods. Housing temperatures remained at 65–75°F (18–23°C) with 40–60% humidity.

Head-plate implantation

At least 1 week before experimentation, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane, 5% in an induction chamber, and maintained at 1–3% in a stereotaxic frame. Following anesthetization and analgesia, an incision was made across the length of the skull and the surrounding connective tissues and muscles were removed with a scalpel blade. A ring-shaped (inner radius 5 mm) titanium headplate was then attached to the skull to allow for head fixation during experimentation using MetaBond, a three-stage dental acrylic (Parkell, Inc) (Waiblinger et al. 2022). MetaBond was made on ice, allowed to thicken, applied to the skull, and allowed to set for five minutes to attach the headplate. The skull was then covered with a thin layer of MetaBond followed by a silicone elastomer (Kwik-Cast Sealant, World Precision Instruments) to protect future injection sites. During the procedure animals were placed on a heating pad to keep body temperature stable. Sterile techniques were employed throughout the procedure to minimize chances of infection, and no antibiotics were given. Opioid and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics were administered (SR-Buprenorphine, SC, post operatively and Ketoprofen, IP, post-operatively). Habituation to head-fixation and training began once animals had fully recovered from head-plate implantation.

Sensory detection task and training

Behavioral training and testing were conducted using a sensory-driven detection task, utilizing the vibrissa/whisker pathway of the mouse. During behavioral training and testing, water intake was restricted to experimental sessions where animals could earn water to satiety. For two days every week, testing was paused, and animals were given access to water ad libitum. Bodyweight was monitored daily and remained relatively stable during constant training. If weight dropped more than ~5 g, supplementary water was given outside of training sessions to maintain the animal’s body weight. We conducted 1–2 training sessions each day comprising 50–300 trials. All experiments were performed in the dark to ensure no visual identification of the galvo-motor whisker actuator. A constant auditory white noise background noise (70 dB) was produced by an arbitrary waveform generator to mask any sound emission from the galvo-motor whisker actuator. All mice were trained on a Go/No-Go detection task employing a protocol as described previously (Ollerenshaw et al. 2012; Stüttgen, Rüter, and Schwarz 2006; Waiblinger et al. 2018, 2019, 2022). In this task, the whisker is deflected at intervals of 6–8 s (flat probability distribution) with a single pulse (detection target). Trials were sorted into four categories, consisting of a “hit”, “miss”, “correct rejection”, or “false alarm”. A trial was considered a “hit” if the animal generated the “Go” response (a lick at a waterspout within 1000 ms of target onset). If the animal did not lick in response to a whisker deflection the trial was considered a “miss”. Additionally, catch trials in which no deflection of the whisker occurred (A = 0°) were considered a “correct rejection” if the animal did not lick (No-Go). If random licks did occur within 1000 ms of catch onset however, the trial was classified as a “false alarm”. Licking that occurred within a 2 s window prior to stimulus onset was punished by resetting time (time-out) and beginning a new inter-trial interval of 6–8 s, drawn at random from a flat probability distribution. These trial types were excluded from the main data analysis.

Whisker Stimulation

Whisker deflections were carried out using a calibrated galvo-motor (galvanometer optical scanner model 621OH, Cambridge Technology) as described previously (Chagas et al. 2013). Dental cement was used to narrow the opening of the rotating arm to prevent whisker motion at the insertion site. A single whisker was inserted into the rotating arm of the motor on the right side of the mouse’s face at a 5 mm (±1 mm tolerance) distance from the skin, directly stimulating the whisker shaft and largely overriding bio elastic whisker properties (Waiblinger et al. 2022). All whiskers were trimmed to avoid artifacts generated by the arm touching other whiskers. Across mice, the whisker chosen differed (C1, C2, D1, or D2) but the same was used throughout the experimentation within each mouse. Custom written code in Matlab and Simulink was designed to elicit voltage commands for the actuator (Ver. 2015b; The MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA). Stimuli were defined as a single event, a sinusoidal pulse (half period of a 100 Hz sine wave, starting at one minimum and ending at the next maximum). The pulse amplitudes used A = [0, 2, 4, 8, 16]°, correspond to maximal velocities: Vmax = [0 628 1256 2512 5023]°/s or mean velocities: Vmean = [0 408 816 1631 3262]°/s and were well within the range reported for frictional slips observed in natural whisker movement (Ritt, Andermann, and Moore 2008; Waiblinger et al. 2022; Wolfe et al. 2008). Figure 2A summarizes the behavior setup, stimulus delivery and logic of the task.

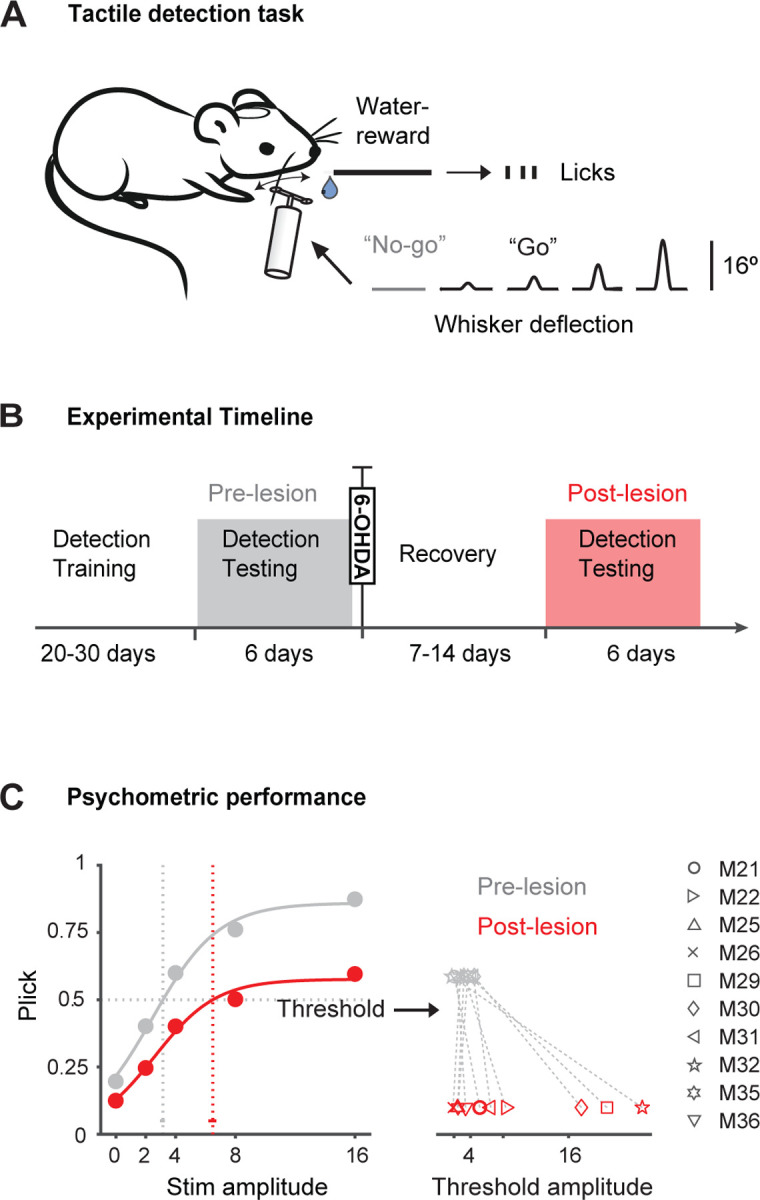

Figure 2. Assessment of sensory capabilities in the 6-OHDA model.

A. Schematic of the behavior setup, stimulus delivery and behavioral detection task. A punctuate whisker deflection (10 ms) has to be detected by the mouse with an indicator lick to receive reward (”Go”). Licking has to be withheld in catch trials (”No-go”). Reward is only delivered upon correct licks. B. Timeline of experiments. Mice were first trained on the detection task. Detection testing was done at least 6 days prior to 6-OHDA injection and repeated after the recovery period. C. Left: Psychometric curves and response thresholds before (gray) and after 6-OHDA injection (red). “Stim amplitude” represents the degree of whisker deflection. Filled circles correspond to the average response probabilities from all animals tested (n=10). Solid curves are logistic fits to the data. Response thresholds are shown as vertical dotted lines with 95 % confidence limits. Right: Response thresholds separately shown for all mice before and after the lesion (gray and red symbols).

6-OHDA lesions

After the collection of behavioral data in the healthy state (pre-lesion, at least 8 sessions of detection testing and one session of rotation), unilateral lesions with 6-OHDA were performed in a subset of animals (6-OHDA, n=10; sham, n=2). The procedures of 6-OHDA injection were adapted from recent studies (Bagga, Dunnett, and Fricker 2015; Ketzef et al. 2017). Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and mounted on a stereotaxic frame as described in the head-plate implantation section above. Kwik cast was removed, and a small craniotomy was created AP: −1.2 mm, ML: +1.2 mm, relative to bregma according to the Mouse Brain Atlas in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Frankin and Paxinos 2008). A unilateral injection of 0.2ul of 6-OHDA (15 mg/ml solution 6-OHDA.HBr) was then administered into the left median forebrain bundle at a rate of 0.1ul/min (depth 4.8–5 mm according to the Mouse Brain Atlas in Stereotaxic Coordinates) via a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Neuros Syringe 700/1700) (Frankin and Paxinos 2008; Thiele, Warre, and Nash 2012). Five-minute waiting periods following both injector insertion and removal were implemented to allow for tissue relaxation. Sham lesioned mice received the correspondent injection protocol with the same volume of vehicle (0.9% saline and 0.02% ascorbic acid). Craniotomies were then sealed with a thin layer of MetaBond and the exposed skull was covered with a silicone elastomer. Opioid and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics were administered (SR-Buprenorphine, SC, post operatively and Ketoprofen, IP, post-operatively). Animals were allowed to recover for 7–21 days until activity and body weight were normal and then behavioral testing continued.

Post-lesion care

6-OHDA lesion mice can suffer from a variety of post-operative complications requiring special post-operative care and a continuous health assessment (Masini et al. 2021). After the surgery, animals were placed in single cage and monitored until fully awake. Additional warmth was provided as an infrared light source. In addition to the standard post-operative monitoring and free access to food and water, a maximum of 3ml sterile saline per day was administered SC to encourage rehydration in lesioned mice. Furthermore, lesioned mice received nutritional supplement in form of DietGel Boost (ClearH2O) as well as sweetened condensed milk (ClearH2O) in food containers on the floor of the cage for 3–10 days (or until body weight stabilized) to increase survival and maintain healthy body weight. The health status of individual mice was assessed daily for a period of 7–21 days post-surgery until activity and body weight were normal. Animals that reached the humane endpoint (defined by the ethical permit) were euthanized.

Rotation

Unilateral 6-OHDA lesions typically cause highly specific, reproducible rotational measurements and the rotation test is a standard measurement of 6-OHDA lesion efficacy (Brooks and Dunnett 2009). After unilateral median forebrain bundle DA depletion, a postural bias towards the side of the lesion is exhibited. Ipsilateral rotation is driven by an imbalance of DA between hemispheres generating decreased movement on the side of lesion. Mice were placed in a clear plexiglass cylinder (40 cm diameter, 20 cm height) and attached via a flexible harness to an automated counter (Rotation Sensors LE902SR, Container & Sensor Support LE902RP, and Individual Counter LE902CC, Panlab). Ipsilateral and contralateral turns relative to the site of the lesion were recorded for 45 minutes. Turns were counted at 45 degrees and findings were presented as percent left turns, where one turn is equivalent to 360 degrees (8 × 45 degrees). The test was performed for all subjects both prior to and following 6-OHDA (n=10) or sham injection (n=2).

TH assessment via immunofluorescence

Following experimentation, animals were transcardially perfused using a 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gage, Kipke, and Shain 2012). Brains were then extracted and post-fixed in PFA for 24 hr before being embedded in OCT for long-term storage at −80°C until sectioning and immunofluorescence. Immunofluorescence staining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) was performed as described previously (Ketzef et al. 2017). Sections of 15 uL were collected using a cryostat (CryoStar NX70), rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently incubated for 1 hr in blocking solution consisting of 5% normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 1% BSA in PBS. Following permeabilization, sections were again rinsed in PBS, then incubated with primary antibody, anti-TH rabbit monoclonal antibody (Millipore Sigma, Billerica, MA) diluted 1:500 in BSA-PBS (1%) at 4°C for 24 hr. Sections were then rinsed with PBS and incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Millipore Sigma, Billerica, MA; Jackson Immunoresearch, Philadelphia, PA) diluted 1:800 in BSA-PBS (1%). Following staining, sections were imaged using either a Zeiss 900 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at 20x magnification or Leica Stellaris 8 (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were quantified using ImageJ to assess percent fluorescence change between lesioned and non-lesioned hemispheres.

TH assessment via high performance liquid chromatography

Sample Preparation & Protein Assay.

The efficacy of lesioning was assessed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Mice were sacrificed in the same way as described previously, but no fixation was performed prior to tissue extraction (Gage, Kipke, and Shain 2012). Brain-hemispheres were then separated into non-lesioned (right) and lesioned (left) and placed immediately on dry ice for flash freezing to preserve monoamine concentrations, specifically DA, in the tissue. The tissue was resuspended in 600 uL 0.1 PCA just above freezing temperature and probe sonicated (Branson 450 Digital Sonifier with microtip, Marshall Scientific) on ice with setting 3 and 30% duty cycle. The homogenates were subsequently centrifuged at 4°C at 10,000 x g for 15 min. Supernatants were transferred to 0.22 uM polyvinylidene fluoride polymer (PVDF) microcentrifuge filter tubes and any remaining matter was removed via filtration through spin filter at 800 rpm for 5 minutes. Concentrations of monoamines were acquired through reverse phase HPLC with electrochemical detection. 1000 uL 2% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was used to dissolve protein pellets. Quantification of protein was carried out in triplicate 96-well microplates with SpectraMax M5e spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) using the BCA method (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific).

HPLC Conditions.

An ESA 5600A CoulArray detection system equipped with an ESA Model 584 pump and an ESA 542 refrigerated autosampler was utilized to perform HPLC. Separations were performed at 28°C via a Hypersil 150 × 3 mm (3uM particle size) C18 column. The mobile phase consisted of 1.6 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid sodium, 75 mM NaH2PO4, 0.025% triethylamine, and 8% acetonitrile at pH 3. A 25 uL sample was injected and eluted isocratically at 0.4 mL/min. A 6210 electrochemical cell (ESA, Bedford, MA) equipped with 5020 guard cell with potential set at 475 mV was used for sample detection. Analytical cell potentials were −175, 200, 350, and 425 mV. Analytes were identified by matching retention time to known standards (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis MO.) and compounds were quantified by comparing peak areas to those of standards on the dominant sensor.

Experimental timeline

Figure 2B outlines the experimental timeline. Over the course of approximately eight weeks, animals completed an entire set of experiments as described below.

Habituation.

Habituation to head-fixation began once animals had fully recovered from head-plate implantation for approximately 1 week. Mice were trained to tolerate head-fixation and got accustomed to the experimental chamber for approximately 1 week.

Detection Training.

Naïve mice received uncued single whisker stimulations in form of a single pulse (A = 16°, Pstim = 0.8) interspersed by catch trials or no stimulation (A = 0°, Pcatch = 0.2). In the early training stage, a water droplet became available immediately after stimulus offset regardless of the animal’s action to condition the animal’s lick response and shape the stimulus reward association. Once animals displayed stable consumption behavior (usually 1–2 sessions), water was only delivered after an indicator lick of the spout within 1000 ms, transitioning the task into an operant conditioning paradigm where the response is only reinforced by reward if it is correctly emitted following stimulus. Learning was measured by calculating the hit p(hit) and false alarm rate p(fa) of successive daily training sessions. A criterion of p(hit) -p(fa) ≥ 0.75 was used to determine successful acquisition of the task. Once an animal reached the criterion, they were considered experts at the task and proceeded into the “Detection Testing” phase.

Detection Testing.

In this phase, the psychometric curve was measured in repeated daily sessions (1–2 sessions per day) for a minimum of six days. The psychometric curve was measured for all animals using a constant stimuli method entailing the presentation of repeated stimulus blocks containing multiple stimulus amplitudes (A = [0, 2, 4, 8, 16]°). In a single trial, one of multiple stimuli was presented after a variable time interval (6–8 s), each with equal probability (uniform distribution, P = 0.2). A stimulus block consisted of a trial sequence containing all stimuli and a catch trial in a pseudorandom order (e.g. each stimulus is presented once per block). One behavioral session consisted of repeated stimulus blocks until the animal disengaged from the task. Animals had to complete a minimum of n=50 trials and a session was considered complete once an entire block of stimuli (A = [0, 2, 4, 8, 16]°) was missed. Therefore, trial numbers varied across animals and sessions (n=50–300 trials). The flexible session length ensures that the data is not affected by the animal’s potential impulsivity or satiation on any given day. Following the six-day testing period, animals were unilaterally injected with 6-OHDA and allowed 7–14 days of recovery. Following recovery animals were again subjected to a “Detection Testing” period which was identical to the one before the lesion to determine the extent of sensory impairments following 6-OHDA lesioning.

Length of testing.

Over about eight weeks, animals completed a whole set of experiments (Fig. 2b). Note, sessions do not directly correlate with days as two sessions per day were performed in some instances and testing was paused during recovery periods. To resolve the actual time frame of testing, we tracked task performance across days, considering different recovery periods (Fig. 4-1 and table 1). In cases where testing was repeated after longer periods (up to 50 days post-lesion), no differences in behavior was observed. N=2 out of 12 animals reached the humane endpoint likely due to 6-OHDA lesioning and were euthanized before the end of the normal testing period.

Table 1:

Number of sessions and days for each animal pre-lesion, in recovery, and post-lesion.

| Animal ID | Pre-lesion | Recovery | Post-lesion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | Sessions | Days | Days | Sessions | |

| 21 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 2* | 3 |

| 22 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 14 | 7 |

| 25 | 6 | 8 | 14 | 15 | 8 |

| 26 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 13 | 10 |

| 29 | 5 | 8 | 23 | 7 | 8 |

| 30 | 7 | 9 | 33 | 3 | 5 |

| 31 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| 32 | 6 | 8 | 15 | 1* | 2 |

| 33 (sham) | 5 | 8 | 19 | 5 | 8 |

| 34 (sham) | 5 | 8 | 19 | 5 | 8 |

| 35 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| 36 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

Animals euthanized due to humane endpoint.

Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

Body weight.

The weight of each subject was measured daily during detection training, detection testing and recovery phases post surgeries. Percent body weight was calculated by identifying the minimum weight within the recovery period (after 6-OHDA and sham injection). Numbers were normalized to each animals’ weight on the day before the lesion. A two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the significance of the effects of lesions on body weight in lesioned versus healthy animals.

Rotation test.

The rotation test was performed within subjects, prior to and following 6-OHDA (n=10) or sham injection (n=2). Each animal performed the test twice, once before and once after injection. A two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the significance of the effects of lesions on rotation in lesioned versus healthy animals.

Detection Training.

Learning was measured for all subjects by calculating the hit p(hit) and false alarm rate p(fa) of successive daily training sessions. The learning curve was measured by calculating a dprime, d’behav, which quantifies the effect size from the observed hit rate and false alarm rate of each training session

| (1) |

where the function , , is the inverse of the cumulative distribution function of the Gaussian distribution. A criterion of d’ = 2.3 (calculated with p(hit) = 0.95 and p(fa) = 0.25) was used to determine the end of the detection training period.

Detection Testing.

The psychometric experiment was performed within subjects, prior to and following 6-OHDA (n=10) or sham injection (n=2). The psychometric curve was measured in repeated daily sessions (1–2 sessions per day) for at least six days.

For average psychometric curves across mice (Fig. 2), response probabilities were averaged from all animals that performed the task pre- and post-lesion. For the analysis of individual subjects (Fig. 3), psychometric data was assessed as response-probabilities averaged across sessions within a given stimulus condition.

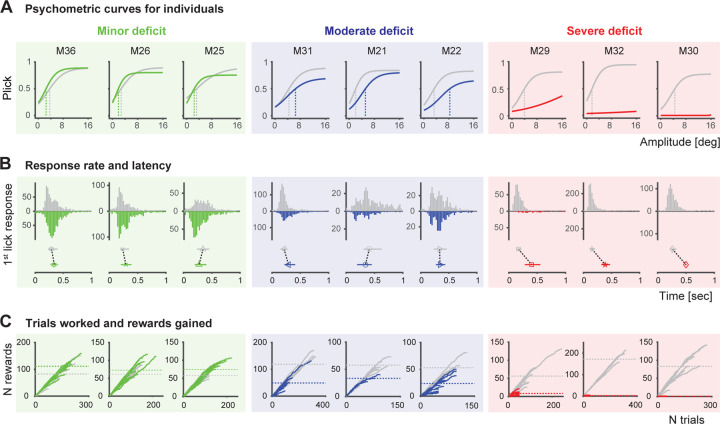

Figure 3. Assessment of sensory capabilities in different individuals.

A. Psychometric curves and response thresholds for each animal performing the detection task before (gray) and after 6-OHDA injection (colored). Mice are ordered by the performance drop (from left to right). Solid curves are logistic fits to response probabilities with different stimulus amplitudes from an individual, averaged across sessions. Response thresholds at P=0.5 are shown as vertical lines. The difference in response thresholds is used to define the 3 categories: minor deficit (threshpost-pre <1, green, n=3), moderate deficit (threshpost-pre>1 and <10, blue, n=3) and severe deficit (threshpost-pre>10, red, n=3). B. Top: Response (1st lick) latencies of individual mice before and after 6-OHDA injection shown as histograms. Bottom: Median 1st lick latencies with percentiles. C. Number of rewards (correct trials) accumulated as a function of trials worked by each animal before and after 6-OHDA injection. Each line corresponds to one session. Dashed horizontal lines correspond to the total rewards per session on average. Figure conventions and order are the same as in A.

Psychometric curves were fitted using Psignifit (Frund, Haenel, and Wichmann 2011; Wichmann and Hill 2001). Briefly, a constrained maximum likelihood method was used to fit a modified logistic function with 4 parameters: α (the displacement of the curve), β (related to the inverse of slope of the curve), γ (the lower asymptote or guess rate), and λ (the higher asymptote or lapse rate) as follows:

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

where is the stimulus on the th trial. Response thresholds were calculated from the average psychometric function for a given experimental condition using Psignifit. The term “response threshold” refers to the inverse of the psychometric function at some performance level with respect to the stimulus dimension. Throughout this study, we use a performance level of 50% (probability of detection of 0.5).

To assess the effects of the lesion on detection behavior, the psychometric curves and response thresholds were compared in lesion and sham lesion animals, from before and after the injection. Statistical differences between psychophysical curves were assessed using bootstrapped estimates of 95% confidence limits for the response thresholds provided by the Psignifit toolbox.

Impairment severity.

Based on the difference in response threshold (at P=0.5) before and after 6-OHDA lesion, animals were classified into three severity groups: “minor”, “moderate” and “severe” deficit. Animals with a minor deficit show no or very small changes in performance (threshpost-pre <1, n=3). Animals with a moderate deficit show a clear decrease in performance (threshpost-pre>1 and <10, n=4), yet they are still performing the task. Animals with a severe deficit display a substantial drop in performance (threshpost-pre>10, n=3) and even stop performing the task.

Results

The current study investigates sensory behavioral deficits in the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) mouse model of PD. To assess the impact of dopamine (DA) depletion on sensory signaling, we utilized a trained detection behavior paradigm in the vibrissa system of the mouse. Unilateral 6-OHDA injections into the mouse medial forebrain bundle (MFB) were performed, and striatal DA depletion was confirmed through histology and standard behavioral assays. Behavioral performance in the sensory-driven detection task was then evaluated over time in both healthy and PD-like states to examine non-motor deficits. Finally, all metrics were compared to provide a comprehensive understanding of the effects of the DA depletion.

Validation of the 6-OHDA mouse model

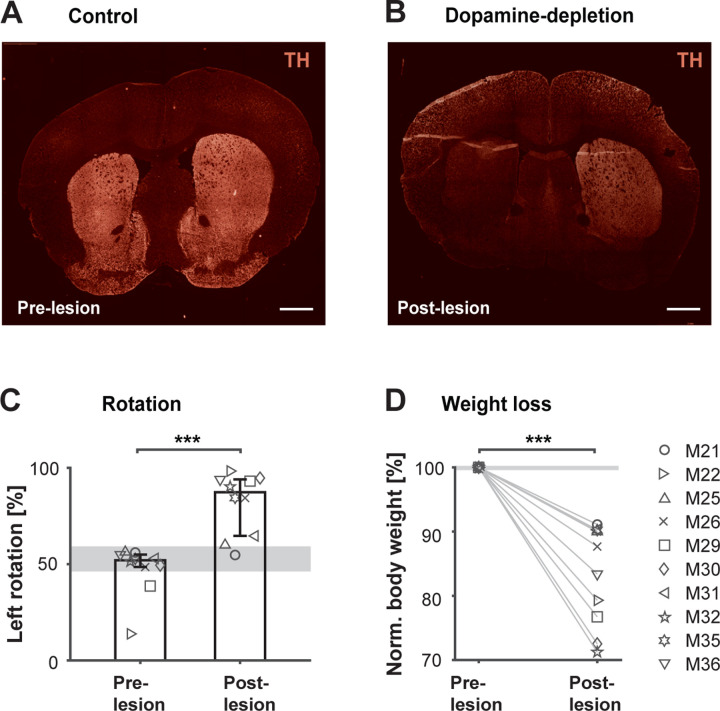

Figure 1 illustrates the validation of the 6-OHDA mouse model through unilateral injections into the left MFB. DA innervation in the striatum was verified by assessing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunofluorescence. In a control mouse, both right and left striatum are intact with no visible difference in fluorescence between hemispheres (Fig. 1A). In contrast, an animal injected with 6-OHDA shows an extensive reduction (81%) in DA innervation in the lesioned versus the non-lesioned hemisphere (Fig. 1B). The amount of DA loss was consistent among all mice that underwent histological validation (median loss: 77.25%, quantified via immunofluorescence, n=8; and 92.7% quantified via high performance liquid chromatography, n=1).

Figure 1. Validation of 6-OHDA mouse model.

A unilateral injection of 0.2ul of 6-OHDA (15 mg/ml solution 6-OHDA.HBr) was administered into the left median forebrain bundle via Hamilton syringe. Mice were allowed to recover for up to 2 weeks before testing continued. A. Coronal sections showing the striatal hemispheres of a control mouse without lesion stained for TH expression. B. Coronal sections of a mouse after 6-OHDA-lesion, stained for TH expression. Over 80% reduction in fluorescence was found between DA-depleted and control hemisphere. Scale bar: 1 mm. C. Percent left turns performed by each mouse in the rotameter test before and after 6-OHDA injection. Bars represent medians across mice with percentiles (n=10). ***P < 0.001, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. D. Body weight before and after 6-OHDA injection. Percent body weight is calculated by identifying the minimum weight within the recovery period. Numbers are normalized to each animals’ weight on the day before the lesion (n=10). ***P < 0.001, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Gray areas represent median range across sham operated mice (n=2).

To further validate DA depletion, all mice underwent a standard rotameter test before and after 6-OHDA injection (Fig. 1C). This test assesses postural bias, reflecting an imbalance of DA between hemispheres and impairing motor abilities on the injection side (Brooks and Dunnett 2009). Prior to 6-OHDA injection, mice exhibited fairly symmetric rotation behavior (median left turns: 52%, n=10). Following 6-OHDA injection, the majority of mice showed a rotational bias consistent with the injection side (median left turns: 87.3%, n=10). Notably, seven mice displayed a clear bias (<80%), while the remaining three showed a minor deficit comparable to sham controls (~60%). To ensure uniformity of lesioning effects, conventional methods often exclude animals with minimal rotation bias (Przedborski and Jackson-Lewis 1995; Ungerstedt and Arbuthnott 1970). In contrast, we conducted a thorough analysis across all animals in this study, including all data to account for potential variability in the effects of 6-OHDA injections among subjects. Our approach, as demonstrated in the results, incorporates a wide range of metrics beyond standard tests, necessitating the comprehensive reporting of all data.

In addition to rotational behavior, we observed fluctuations in body weight following DA depletion (Fig. 1D), a common phenomenon in rodents treated with 6-OHDA (Barata-Antunes et al. 2020; Masini et al. 2021). Despite receiving extensive post-operative care, all subjects experienced weight loss within 7–14 days post-6-OHDA injection. Importantly, we noted a significant, positive correlation between the observed weight changes and rotational behavior, with subjects displaying higher degrees of weight loss also exhibiting more pronounced rotational biases post-6-OHDA injection (Pearson correlation coefficient r=.81, p<.01, n=10).

6-OHDA lesion affects detection behavior

Twelve mice were trained on a tactile Go/No-Go detection task (Ollerenshaw et al. 2012; Stüttgen, Rüter, and Schwarz 2006; Waiblinger et al. 2018, 2019, 2022), and their performance was evaluated over time in the healthy and PD-like state. Figure 2A depicts the task setup and logic, where mice responded to whisker deflections by either licking a waterspout (Go) or refraining from licking (No-Go) in the absence of a stimulus. Reward delivery depended on correct responses and “time-outs” were used to penalize/discourage impulsive licking. Further details regarding the task are provided in the Methods.

Figure 2B outlines the experimental timeline, with procedures detailed in the Methods section. Briefly, over eight weeks, animals underwent a series of experiments. This included “Detection Training,” where animals received single whisker stimulations or no stimulation. Learning progress was assessed daily, and upon meeting criteria, animals proceeded to “Detection Testing.” During this phase, the psychometric curve was measured in repeated daily sessions for a minimum of 6 days. Following this testing period, animals underwent unilateral 6-OHDA injection and allowed 7–14 days of recovery. After the recovery period, animals underwent another round of “Detection Testing” post-lesion, mirroring the pre-lesion phase, to assess the extent of behavioral impairments following 6-OHDA lesioning.

Figure 2C illustrates averaged psychometric curves from a subset of mice (n=10) before (gray) and after 6-OHDA injection (red) across multiple sessions. The marked shift in the psychometric curve post-lesion signifies a decline in performance, with varying effects noted among individual mice. This decline in average psychometric performance implies compromised tactile sensation following DA depletion. While evident degradation in performance was observed, complete abolishment was not consistently present. This variability could stem from the degree of DA depletion, inter-subject variability, or a combination of both. The high variability observed precludes significant differences in standard statistical testing. Further investigation is warranted given the variability across several measures.

6-OHDA lesion causes various deficits across individuals

To explore the behavioral response variability in the 6-OHDA lesioned mice in more detail, we examined multiple behavioral metrics for each animal (Figure 3), including sensory detection thresholds, motor lick responses, as well as overall task engagement and motivation.

Figure 3A displays psychometric curves and response thresholds for nine representative mice that performed the detection task in both the healthy (gray) and DA depleted (colored) states. When analyzing the data individually, a pattern of varying task performance emerges allowing us to order subjects according to their impairment severity. Based on the difference in response threshold (at P=0.5) before and after 6-OHDA lesion, animals were classified into three severity groups; “minor”, “moderate” and “severe” deficit (Fig. 3A, from left to right). Animals with minor deficits show minimal performance changes (threshpost-pre<1, green compared to gray) with a slight potential improvement. Animals with a moderate deficit show a clear decrease in performance (threshpost-pre>1 and <10, blue compared to gray), yet they are still performing the task. Animals with a severe deficit display a substantial drop in performance (threshpost-pre>10, red compared to gray) and even stop performing the task.

To assess whether the decline in performance correlated with the inability of animals to respond following DA depletion, indicating a motor aspect to the behavioral deficit, we analyzed indicator lick response rates (Fig. 3B, top) and first lick latencies (Fig. 3B, bottom). Animals with minor deficits have similar response rates and latencies before and after lesioning (green compared to gray). Intriguingly, in the moderate case, although licking behavior diminishes after lesioning, it persists without a noticeable increase in latency (blue compared to gray). This suggests that these animals retain the ability to generate timed motor responses, indicating intact motor capabilities. However, the observed compromise in sensory-motor capabilities underscores the likely presence of a sensory deficit. In severe cases, overall task activity drastically decreases, with subjects exhibiting minimal or no directed lick responses (red compared to gray), indicating potential motor impairments in addition to any underlying sensory deficits. For this group of animals, increased response latency is not a reliable metric due to the absence of lick responses for latency estimation. Categorizing severe cases as purely motor-related may be an oversimplification, as there could be involvement of both motor and sensory aspects. Importantly, these animals demonstrate eating, drinking, and grooming behaviors outside the setup, suggesting some degree in resilience in motor control.

Associated with task performance is the accumulation of rewards, representing the total instances of an animal successfully receiving a reward (Fig. 3C, vertical axis). To quantify this, we computed the average total number of rewards per session both before (gray dashed lines) and after the lesion (colored dashed lines). This metric serves as an approximation of the animal’s motivation, given that rewards act as a primary motivator for task engagement. The number of trials completed (Fig. 3C, horizontal axis) serves as a proxy for the overall engagement in the task. It is important to note that animals were required to complete a minimum of 50 trials, and a session was considered complete once an entire block of stimuli (A = [0, 2, 4, 8, 16]°) was missed. Consistent with their stable performance, animals with minor deficits accumulate a comparable reward count before and after the lesion (left column). In some cases, animals even gain a few more rewards by working more trials. Animals with moderate deficits (middle column), however, show a clear decrease in reward accumulation and reduced task engagement post lesioning. As severity of impairment increases, the number of rewards gained and total number of trials worked decreases drastically compared to the healthy state. Severely impaired animals (right column) are held in the setup for the minimum number of trials with very limited activity.

Our examination of multiple behavioral metrics for individual subjects revealed a spectrum of impairments, reflecting variability in task performance among lesioned animals. This diversity manifested in changes to response probabilities, response rates, latency, and associated reward accumulation. Notably, our analysis enabled the classification of severity and identified a sensory-only component in the moderate cases, alongside motivational factors.

6-OHDA lesion causes persistent deficits over time

Unlike the gradual progression of PD symptoms observed clinically, 6-OHDA induces a swift and complete lesion in the nigrostriatal pathway, commonly injected into the substantia nigra or medial forebrain bundle (Agid et al. 1973; Przedborski and Jackson-Lewis 1995; Tieu 2011). Studies on the motor symptom progression indicate that 6-OHDA-induced lesions can be established with high stability over time (Antony, Diederich, and Balling 2011; Iancu et al. 2005; Quiroga-Varela et al. 2017). However, the progression of non-motor behavioral deficits in this model remains poorly understood. To assess potential changes over time, we systematically analyzed the data from the detection experiments by evaluating behavioral performance across sessions and days in both healthy and PD-like states (Figure 4). Animals were once again categorized into three severity groups (minor, moderate, and severe deficit) as explained in the previous section.

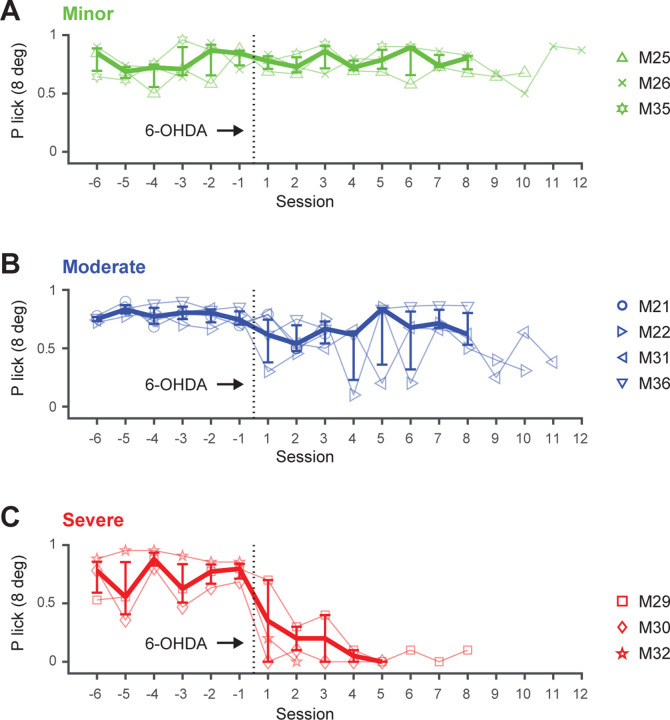

Figure 4. Persistence of sensory deficits in the 6-OHDA mouse model.

The 3 categories, minor, moderate and severe, are based on the difference in thresholds from the psychometric curves. A. Detection performance (P correct lick with 8 degree whisker deflection) over time (sessions) for animals with minor deficits, before and after the 6-OHDA lesion. B. Performance for animals with moderate deficits. C. Performance for animals with severe deficits. Symbols represent individual mice. Thick lines represent medians across mice with percentiles (n=3–4).

Figure 4A illustrates the detection performance over multiple sessions for three animals with minor deficits, both before and after the 6-OHDA lesion. Performance is represented as the probability of a correct lick with a salient stimulus (8-degree whisker deflection) across 6 pre-lesion sessions and up to 12 post-lesion sessions for each animal. Before the lesion, animals exhibit slight variability in performance. After the lesion, performance remains unchanged, with consistent levels observed across sessions, suggesting that the perceptual capabilities linked to the task likely remained intact in these mice.

Figure 4B illustrates the detection performance over time for four animals exhibiting moderate deficits. While some individuals show an initial decline in performance shortly after the lesion, noticeable variability emerges across sessions, occasionally within a single day. The session-to-session variability underscores the complexity of the animals’ responses, potentially elucidating the coexistence of sensory and motivational deficits alongside preserved motor capabilities within the detection task, as previously observed for this group of mice (Figure 3, blue panels).

Figure 4C illustrates a substantial decline in detection performance in three severely affected animals shortly after the 6-OHDA injection, evident within the initial two sessions. Following the lesion, variability in performance quickly diminishes in the severe group, reaching nearly zero levels. This pronounced and persistent change in performance confirms the previous observation that severely impaired animals exhibit very limited activity in response to the DA depletion.

Notably, recovery periods varied among the three groups of mice, resulting in differences in the data presented regarding the lesion timeframe. Additionally, due to occasional repetition of sessions within a day and pauses on weekends, sessions do not directly correspond to days. To address this, performance was tracked across days in a separate analysis, considering these variations (Figure. 4-1 and Table 1). The day-based analysis yields results consistent with the session-based analysis, confirming that task performance does not improve or degrade over time within the measured timeframe.

Utilizing multiple metrics for comprehensive lesion assessment

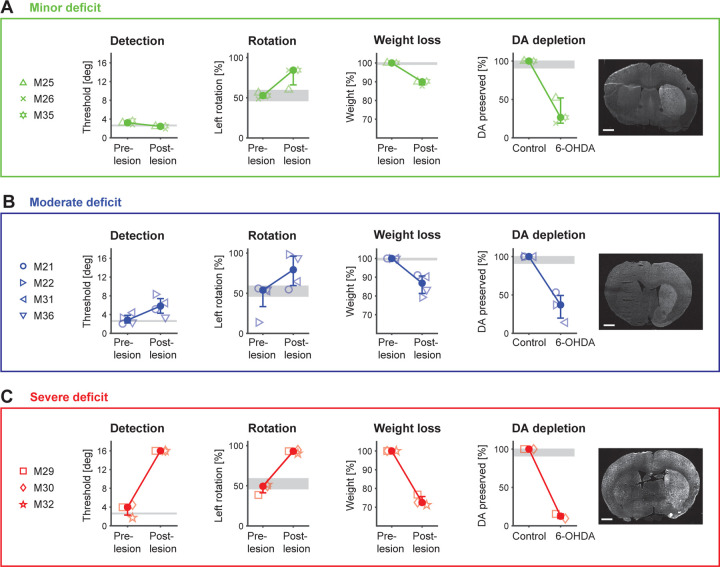

Our findings underscore that inducing unilateral DA depletion leads to rotational defects, weight loss, and diverse behavioral impairments, as evidenced in a sensory-driven detection task. While these metrics have been discussed separately thus far, we now compare them to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the lesion effects. Figure 5 presents an overview of all metrics assessed in this study before and after the 6-OHDA lesion, comparing histological findings, rotation data, weight loss, and behavioral data from the detection task. These metrics are compared for each of the three severity groups – minor (green), moderate (blue), and severe deficit (red) – to elucidate the distinct effects observed within each group.

Figure 5. Comparison of multiple behavioral metrics and DA depletion in the 6-OHDA mouse model.

A. Minor deficit group (n=3). Detection: Perceptual thresholds (at P=0.5) from the detection task for all mice before and after the 6-OHDA lesion. Rotation: Percent left turns performed by animals in the rotameter test before and after 6-OHDA lesion. Weight loss: Maximum weight loss during the recovery period for each animal. DA depletion: Left. The percentage of DA preservation is quantified from histological analysis for all mice of this group. Right. Coronal sections of an example mouse after 6-OHDA-lesion, stained for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression. B. Same metrics for the moderate deficit group (n=4). C. Same metrics for the severe deficit group (n=3). Symbols represent individual mice. Solid filled circles represent medians across mice with percentiles. Gray areas represent median range across sham operated mice (n=2). Note, histological assessment was performed for a subset of mice (minor deficit n=3; moderate deficit n=3.; severe deficit n=2). Scale bars: 1 mm.

Figure 5A summarizes all metrics for animals with minor deficits. By construction, animals in this group demonstrate consistent detection thresholds before and after the lesion, indicating stable sensory behavioral performance. In some cases, performance may have even slightly improved. Strikingly, these animals exhibit a bias in rotation behavior, predominantly favoring left turns (60–84%), and experience a modest loss of body weight (10–12%) during the recovery period. Histological analysis reveals a substantial reduction (48–81%) in DA innervation in the lesioned hemisphere, as quantified via immunofluorescence. This discrepancy between stable detection performance and DA depletion metrics strongly suggests that the lesion may have impacted certain physiological functions unrelated to the detection task or that the animals were able to compensate in some manner.

Figure 5B summarizes all metrics for animals with moderate deficits. By construction, animals with moderate deficits demonstrate a clear increase in detection threshold (despite lack of apparent motor deficit – see Fig. 3), consistent with a sensory deficit post-6-OHDA lesion. Animals in this group exhibit varying left turn biases (55–98%), suggesting inconsistent motor impairment. This variability is also reflected in weight loss during the recovery period (9–21%). Histological analysis confirms a substantial reduction (47–86%) in DA innervation, indicating the efficacy of the lesion. The observed decrease in detection performance alongside inconsistent motor impairments further underscores the likelihood of isolated sensory or motivational deficits in this group of mice, emphasizing the inherent variability in lesion effects.

Figure 5C summarizes all metrics for animals with severe deficits. By design, animals with severe deficits exhibit a substantial increase in detection threshold following 6-OHDA injection. These mice display a pronounced rotational bias (90–95%) with minimal variability and experience substantial weight loss during the extended recovery period (23–29% within 21 days). Histological analysis for this group reveals the most profound reduction (85–90%) in DA innervation among the three levels of behavioral deficit, emphasizing the severity of the 6-OHDA lesion within this group. This pronounced change in all metrics confirms the previous observation that severely impaired animals exhibit very limited activity in response to the lesion.

In summary, our study demonstrates the diverse effects of unilateral DA depletion induced by 6-OHDA injection. Mice with severe deficits in sensory-driven behavior consistently exhibited pronounced impairments across all measures, indicating robust and consistent effects. However, while standard measures like rotation bias and histological assessment are crucial for evaluating DA depletion, their correlation with sensory task performance is sometimes limited. For instance, mice with minor sensory deficits still showed substantial DA depletion alongside rotational bias and weight loss. Interestingly, mice with moderate declines in sensory performance displayed the greatest variability across metrics, suggesting complex interactions between these factors. These findings emphasize the necessity of comprehensive assessment using multiple behavioral parameters to fully capture the effects of DA depletion.

Discussion

In this study, we investigate the relationship between DA depletion and behavior within the 6-OHDA mouse model, conducting a comprehensive exploration of impairments. Our findings illustrate that inducing unilateral DA depletion leads to rotational defects, weight loss, and a wide range of diverse sensory- and motor deficits, particularly evident in a behavioral detection task. The variations in task performance observed among animals underscore the inherent complexity of the model. By employing multiple metrics for comprehensive lesion assessment and dissecting sensory and motor components, our study offers detailed insights into the contributing factors underlying the observed diversity of impairments.

While Parkinson’s Disease diagnosis traditionally relies on motor symptoms, emerging evidence of sensory deficits suggests a potential window for early diagnostic methods (Juri, Rodriguez-Oroz, and Obeso 2010; Konczak et al. 2012; Prätorius, Kimmeskamp, and Milani 2003; Richardson and Sussman 2019). Despite not replicating PD’s natural progression, the 6-OHDA mouse model provides a stable platform for characterizing deficits in PD-like states, induced by DA depletion in the striatum (Bagga, Dunnett, and Fricker 2015; Francardo et al. 2011; Masini et al. 2021). This understanding of the model’s fidelity extends to investigating the question: How does DA depletion impact sensory processing? Our findings reveal a wide spectrum of behavioral deficits, highlighting the complexity of the relationship between DA depletion and sensory processing. Within this spectrum, we observe both increased and decreased sensitivity in sensory detection performance. Such impaired tactile acuity has been reported in animal models of PD (Romero-Sánchez et al. 2020) as well as in clinical settings (Kesayan et al. 2015). While our study primarily focuses on the behavioral outcomes of DA depletion, the underlying mechanisms by which this neurotransmitter deficit affects sensory function are complex and multifaceted. One possible avenue for exploration is through the anatomy of the basal ganglia and its connections with sensory processing regions in the cortex. DA plays a crucial modulatory role in these circuits, and its depletion may disrupt the transmission of sensory information or alter the processing of sensory signals, leading to changes in detection performance. Studies reporting altered striatal sensory responses (Ketzef et al. 2017; Reig and Silberberg 2014) underscore the potential impact of DA depletion on sensory processing. In contrast to studies involving electrophysiology on non-behaving or anesthetized animals, our study deliberately focuses on understanding behavioral outcomes in the natural, behaving state, allowing speculation on the precise impact of striatal changes on sensory functions. Further research utilizing electrophysiology in behaving animals is necessary to elucidate the specific neural pathways and mechanisms underlying these effects.

PD patients exhibit a wide range of non-motor impairments, including alterations in olfactory, auditory, tactile, nociceptive, thermal, and proprioceptive perception (Oppo et al. 2020; Jafari, Kolb, and Mohajerani 2020; Kesayan et al. 2015; José Luvizutto et al. 2020; Brim and Struhal 2021). In our investigation, we focus on tactile sensation mediated through whisker deflection in mice, using the conserved rodent “whisker to barrel” pathway as a reliable model for tactile-sensory stimulation and processing. How do findings in the vibrissa system relate to other sensory pathways? While our investigation primarily centers on this model, our behavioral paradigm and findings may have broader implications across sensory modalities. The principles of sensory integration and DA-mediated modulation observed in our study could extend to other sensory pathways with similar organization, including vision, hearing, taste, and smell. Given dopamine’s known influence on neural circuits involved in diverse sensory modalities, alterations in DA levels could impact sensory perception and processing across various modalities. Therefore, our study may provide valuable insights into the broader mechanisms underlying sensory deficits in PD and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Our findings unveil a large spectrum of impairments following DA depletion, revealing high variability among individuals. Where does this variability come from? It may arise from multiple factors. Differences in the precise placement and depth of the injection within the medial forebrain bundle can lead to variations in the extent of DA depletion, impacting different subregions of the striatum (Masini et al. 2021). Despite controlling factors such as age, genetic background, and environmental conditions, variables like overall health status, social rank among cage mates, or overall activity level may influence vulnerability to neurotoxic insults. These factors can impact the magnitude of DA depletion induced by 6-OHDA injections, further contributing to the observed variability in behavioral outcomes. Furthermore, intrinsic variability in behavior is evident even among healthy subjects. Overall, the variability following 6-OHDA injections likely arises from a combination of factors, including lesion accuracy, neuronal susceptibility, pharmacokinetic factors, and general variability in behavioral responses.

Our study challenges the presumed direct correlation between behavioral deficits and the extent of DA depletion, which is typically evaluated using rotation bias (Przedborski and Jackson-Lewis 1995; Ungerstedt and Arbuthnott 1970). While such tests are essential for assessing DA depletion in vivo, they have limitations in capturing the full behavioral spectrum. Excluding subjects with limited rotation bias from analysis narrows the perspective within this animal model, potentially overlooking important aspects in the relationship between DA depletion and behavior. This is particularly notable in our moderate cases, which show variable rotation bias but clear deficits in stimulus detection without altered response latencies, indicating isolated sensory impairments. Additionally, these moderate cases often show strong session-to-session fluctuations and achieve fewer rewards, indicating a possible motivational deficit. These findings underscore the complexity of lesion-induced behavioral changes and warrant a reevaluation of traditional interpretations of PD models, emphasizing the need to consider multiple behavioral metrics and individual variability in lesion effects.

The histological assessment, although limited to a subset of mice, reveals substantial DA depletion, regardless of the assessed sensory behavioral deficit. The small increments in DA depletion between severity groups underscore the impact of even slight changes in DA levels on behavior and physiology. While our model does not mirror PD’s natural progression, it predicts an intriguing pattern: Minor deficits indicate substantial DA loss but stable sensory detection, suggesting compensatory mechanisms. Moderate deficits involve compromised sensory and motivational aspects, eventually leading to severe deficits akin to classic motor symptoms. This pattern provides implications for understanding the progression of PD. Further exploration with genetic mouse models of PD progression (Dovonou et al. 2023) and rigorous histological or pathophysiological assessments could validate these predictions. Such a comprehensive approach would elucidate the underlying mechanisms contributing to the observed behavioral changes across disease progression.

In summary, our study sheds light on sensory deficits in the 6-OHDA mouse model, providing insights into early PD symptoms. The proposed behavioral task proves valuable for uncovering these symptoms and other hidden variables. Additionally, our severity-based classification system suggests the ability to capture different disease stages depending on lesion extent, hinting at the potential for early PD detection. This underscores the versatility of the 6-OHDA model in simulating various disease stages. To fully leverage the potential of the behavioral task and reveal circuitry alterations, further research with disease progression models, longitudinal measurements, and physiological assessments is warranted. This approach holds promise for deepening our understanding of PD and advancing intervention and treatment development.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT.

This study explores sensory-motor aspects of Parkinson’s disease using a 6-OHDA mouse model. Leveraging the mouse whisker system, we reveal diverse deficits in tactile sensation behavior due to dopamine depletion. Our findings emphasize the importance of sensory assessments in understanding the diverse spectrum of PD symptoms.

Acknowledgements:

S.R.L. was supported by a McCamish Parkinson’s Disease Innovation Program Blue Sky grant. E.J.H was supported by a McCamish Parkinson’s Disease Innovation Program Blue Sky grant and NIH R01NS124764. N.H.C., G.B.S and C.W. were supported by NIH Brain Grants RF1NS128896 and R01NS104928. This study was supported by the Emory University Emory Integrated Cellular Imaging Core Facility (RRID:SCR_023534), with special thanks to April Reedy for her advice on experimental design and image acquisition. We thank the Emory HPLC Bioanalytical Core (EHBC), which was supported by the Emory University School of Medicine and the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378. Additionally, we thank Aqua Asberry from the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Research Histology Core for her assistance in specimen embedding and cryostat sectioning.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests

References

- Aeed Fadi, Cermak Nathan, Schiller Jackie, and Schiller Yitzhak. 2021. “Intrinsic Disruption of the M1 Cortical Network in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease.” Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society 36(7): 1565–77. doi: 10.1002/mds.28538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agid Yves, Javoy France, Glowinski Jacques, Bouvet Dominique, and Sotelo Constantino. 1973. “Injection of 6-Hydroxydopamine into the Substantia Nigra of the Rat. II. Diffusion and Specificity.” Brain Research 58(2): 291–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony Paul M. A., Diederich Nico J., and Balling Rudi. 2011. “Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Models in Translational Research.” Mammalian Genome 22(7–8): 401–19. doi: 10.1007/s00335-011-9330-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagga V., Dunnett S.B., and Fricker R.A. 2015. “The 6-OHDA Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease – Terminal Striatal Lesions Provide a Superior Measure of Neuronal Loss and Replacement than Median Forebrain Bundle Lesions.” Behavioural Brain Research 288: 107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Antunes Sandra, Teixeira Fábio G., Mendes-Pinheiro Bárbara, Domingues Ana V., Vilaça-Faria Helena, Marote Ana, Silva Deolinda, Sousa Rui A., and Salgado António J. 2020. “Impact of Aging on the 6-OHDA-Induced Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21(10): 3459. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchi Igor, D’Andrea Ivana, Armida Monica, Cassano Tommaso, Pèzzola Antonella, Potenza Rosa Luisa, Morgese Maria Grazia, Popoli Patrizia, and Alleva Enrico. 2008. “Nonmotor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: Investigating Early-phase Onset of Behavioral Dysfunction in the 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned Rat Model.” Journal of Neuroscience Research 86(9): 2050–61. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim Bianca, and Struhal Walter. 2021. “Thermoregulatory Dysfunctions in Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease.” In International Review of Movement Disorders, Elsevier, 285–98. doi: 10.1016/bs.irmvd.2021.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Simon P., and Dunnett Stephen B. 2009. “Tests to Assess Motor Phenotype in Mice: A User’s Guide.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10(7): 519–29. doi: 10.1038/nrn2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas André M., Theis Lucas, Sengupta Biswa, Stüttgen Maik C., Bethge Matthias, and Schwarz Cornelius. 2013. “Functional Analysis of Ultra High Information Rates Conveyed by Rat Vibrissal Primary Afferents.” Frontiers in Neural Circuits 7. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovonou Axelle, Bolduc Cyril, Linan Victoria Soto, Gora Charles, Peralta Modesto R. Iii, and Lévesque Martin. 2023. “Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease: Bridging the Gap between Disease Hallmarks and Research Questions.” Translational Neurodegeneration 12(1): 36. doi: 10.1186/s40035-023-00368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francardo Veronica, Recchia Alessandra, Popovic Nataljia, Andersson Daniel, Nissbrandt Hans, and Angela Cenci M. 2011. “Impact of the Lesion Procedure on the Profiles of Motor Impairment and Molecular Responsiveness to L-DOPA in the 6-Hydroxydopamine Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease.” Neurobiology of Disease 42(3): 327–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankin Keith B.J., and Paxinos George. 2008. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (2008). 3rd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Frund I., Haenel N. V., and Wichmann F. A. 2011. “Inference for Psychometric Functions in the Presence of Nonstationary Behavior.” Journal of Vision 11(6): 16–16. doi: 10.1167/11.6.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage Gregory J., Kipke Daryl R., and Shain William. 2012. “Whole Animal Perfusion Fixation for Rodents.” Journal of Visualized Experiments (65): 3564. doi: 10.3791/3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iancu Ruxandra, Mohapel Paul, Brundin Patrik, and Paul Gesine. 2005. “Behavioral Characterization of a Unilateral 6-OHDA-Lesion Model of Parkinson’s Disease in Mice.” Behavioural Brain Research 162(1): 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Zahra, Kolb Bryan E., and Mohajerani Majid H. 2020. “Auditory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease.” Movement Disorders 35(4): 537–50. doi: 10.1002/mds.28000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luvizutto José, Gustavo, Brito Thanielle Souza Silva, Neto Eduardo De Moura, and Souza Luciane Aparecida Pascucci Sande De. 2020. “Altered Visual and Proprioceptive Spatial Perception in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 127(1): 98–112. doi: 10.1177/0031512519880421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juri Carlos, Rodriguez-Oroz MariCruz, and Obeso Jose A. 2010. “The Pathophysiological Basis of Sensory Disturbances in Parkinson’s Disease.” Journal of the Neurological Sciences 289(1–2): 60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesayan Tigran, Lamb Damon G., Falchook Adam D., Williamson John B., Salazar Liliana, Malaty Irene A., McFarland Nikolaus R., et al. 2015. “Abnormal Tactile Pressure Perception in Parkinson’s Disease.” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 37(8): 808–15. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2015.1060951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketzef Maya, Spigolon Giada, Johansson Yvonne, Bonito-Oliva Alessandra, Fisone Gilberto, and Silberberg Gilad. 2017. “Dopamine Depletion Impairs Bilateral Sensory Processing in the Striatum in a Pathway-Dependent Manner.” Neuron 94(4): 855–865.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konczak Jürgen, Sciutti Alessandra, Avanzino Laura, Squeri Valentina, Gori Monica, Masia Lorenzo, Abbruzzese Giovanni, and Sandini Giulio. 2012. “Parkinson’s Disease Accelerates Age-Related Decline in Haptic Perception by Altering Somatosensory Integration.” Brain 135(11): 3371–79. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad M., Picconi B., Lindgren H., and Cenci M.A. 2004. “A Model of L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in 6-Hydroxydopamine Lesioned Mice: Relation to Motor and Cellular Parameters of Nigrostriatal Function.” Neurobiology of Disease 16(1): 110–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini Débora, Plewnia Carina, Bertho Maëlle, Scalbert Nicolas, Caggiano Vittorio, and Fisone Gilberto. 2021. “A Guide to the Generation of a 6-Hydroxydopamine Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease for the Study of Non-Motor Symptoms.” Biomedicines 9(6): 598. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9060598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollerenshaw Douglas R., Bari Bilal A., Millard Daniel C., Orr Lauren E., Wang Qi, and Stanley Garrett B. 2012. “Detection of Tactile Inputs in the Rat Vibrissa Pathway.” Journal of Neurophysiology 108(2): 479–90. doi: 10.1152/jn.00004.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppo Valentina, Melis Marta, Melis Melania, Barbarossa Iole Tomassini, and Cossu Giovanni. 2020. “‘Smelling and Tasting’ Parkinson’s Disease: Using Senses to Improve the Knowledge of the Disease.” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 12: 43. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pont-Sunyer Claustre, Hotter Anna, Gaig Carles, Seppi Klaus, Compta Yaroslau, Katzenschlager Regina, Mas Natalia, et al. 2015. “The Onset of Nonmotor Symptomsin Parkinson’s Disease (the ONSET PD Study).” Movement Disorders 30(2): 229–37. doi: 10.1002/mds.26077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prätorius B, Kimmeskamp S, and Milani T.L. 2003. “The Sensitivity of the Sole of the Foot in Patients with Morbus Parkinson.” Neuroscience Letters 346(3): 173–76. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski S, and Jackson-Lewis V. 1995. “DOSE-DEPENDENT LESIONS OF THE DOPAMINERGIC NIGROSTRIATAL PATHWAY INDUCED BY INTRASTRIATAL INJECTION OF 6-HYDROXYDOPAMINE.” Neuroscience 67(3): 631–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga-Varela A., Aguilar E., Iglesias E., Obeso J.A., and Marin C. 2017. “Short- and Long-Term Effects Induced by Repeated 6-OHDA Intraventricular Administration: A New Progressive and Bilateral Rodent Model of Parkinson’s Disease.” Neuroscience 361: 144–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reig Ramon, and Silberberg Gilad. 2014. “Multisensory Integration in the Mouse Striatum.” Neuron 83(5): 1200–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson Kelly C., and Sussman Joan E. 2019. “Intensity Resolution in Individuals With Parkinson’s Disease: Sensory and Auditory Memory Limitations.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 62(9): 3564–81. doi: 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-H-18-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritt Jason T., Andermann Mark L., and Moore Christopher I. 2008. “Embodied Information Processing: Vibrissa Mechanics and Texture Features Shape Micromotions in Actively Sensing Rats.” Neuron 57(4): 599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sánchez Héctor Alonso, Mendieta Liliana, Austrich-Olivares Amaya Montserat, Garza-Mouriño Gabriela, Mirón Marcela Benitez-Diaz, Coen Arrigo, and Godínez-Chaparro Beatriz. 2020. “Unilateral Lesion of the Nigroestriatal Pathway with 6-OHDA Induced Allodynia and Hyperalgesia Reverted by Pramipexol in Rats.” European Journal of Pharmacology 869: 172814. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stüttgen Maik C., Rüter Johannes, and Schwarz Cornelius. 2006. “Two Psychophysical Channels of Whisker Deflection in Rats Align with Two Neuronal Classes of Primary Afferents.” The Journal of Neuroscience 26(30): 7933–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1864-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele Sherri L., Warre Ruth, and Nash Joanne E. 2012. “Development of a Unilaterally-Lesioned 6-OHDA Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease.” Journal of Visualized Experiments (60): 3234. doi: 10.3791/3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieu K. 2011. “A Guide to Neurotoxic Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 1(1): a009316–a009316. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt Urban, and Arbuthnott Gordon W. 1970. “Quantitative Recording of Rotational Behavior in Rats after 6-Hydroxy-Dopamine Lesions of the Nigrostriatal Dopamine System.” Brain Research 24(3): 485–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiblinger Christian et al. 2022. “Emerging Experience-Dependent Dynamics in Primary Somatosensory Cortex Reflect Behavioral Adaptation.” Nature Communications 13(1): 534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiblinger Christian, Whitmire Clarissa J., Sederberg Audrey, Stanley Garrett B., and Schwarz Cornelius. 2018. “Primary Tactile Thalamus Spiking Reflects Cognitive Signals.” The Journal of Neuroscience 38(21): 4870–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2403-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiblinger Christian et al. 2019. “Stimulus Context and Reward Contingency Induce Behavioral Adaptation in a Rodent Tactile Detection Task.” The Journal of Neuroscience 39(6): 1088–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann Felix A., and Jeremy Hill N. 2001. “The Psychometric Function: I. Fitting, Sampling, and Goodness of Fit.” Perception & Psychophysics 63(8): 1293–1313. doi: 10.3758/BF03194544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe Jason, Hill Dan N, Pahlavan Sohrab, Drew Patrick J, Kleinfeld David, and Feldman Daniel E. 2008. “Texture Coding in the Rat Whisker System: Slip-Stick Versus Differential Resonance” ed. Stanley Garrett B. PLoS Biology 6(8): e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.