Abstract

Background

Poor compliance with treatment often means that many people with schizophrenia or other severe mental illness relapse and may need frequent and repeated hospitalisation. Information and communication technology (ICT) is increasingly being used to deliver information, treatment or both for people with severe mental disorders.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of psychoeducational interventions using ICT as a means of educating and supporting people with schizophrenia or related psychosis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (2008, 2009 and September 2010), inspected references of identified studies for further trials and contacted authors of trials for additional information.

Selection criteria

All clinical randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing ICT as a psychoeducational and supportive tool with any other type of psychoeducation and supportive intervention or standard care.

Data collection and analysis

We selected trials and extracted data independently. For homogenous dichotomous data we calculated fixed‐effect risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD). We assessed risk of bias using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Main results

We included six trials with a total of 1063 participants. We found no significant differences in the primary outcomes (patient compliance and global state) between psychoeducational interventions using ICT and standard care.

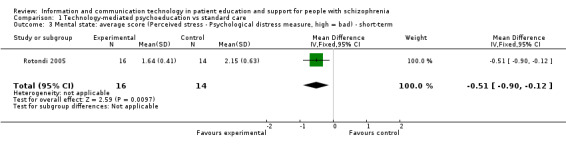

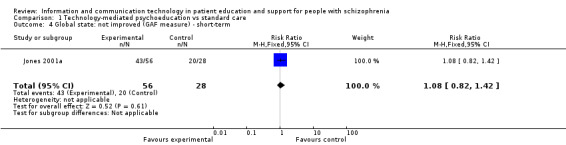

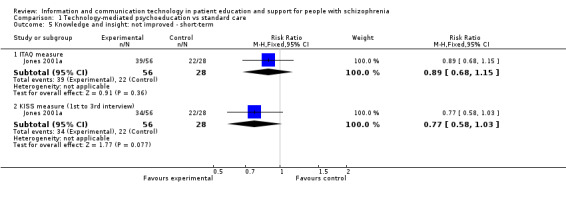

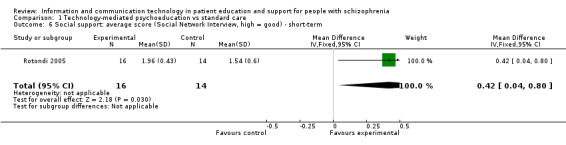

Technology‐mediated psychoeducation improved mental state in the short term (n = 84, 1 RCT, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.00; n = 30, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.90 to ‐0.12) but not global state (n = 84, 1 RCT, RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.42). Knowledge and insight were not effected (n = 84, 1 RCT, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.15; n = 84, 1 RCT, RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.03). People allocated to technology‐mediated psychoeducation perceived that they received more social support than people allocated to the standard care group (n = 30, 1 RCT, MD 0.42, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.80).

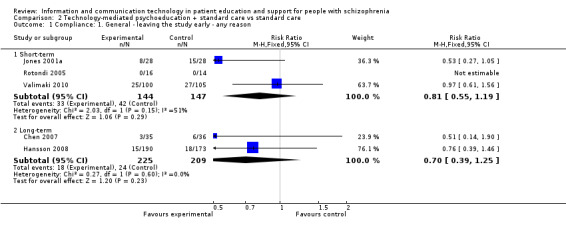

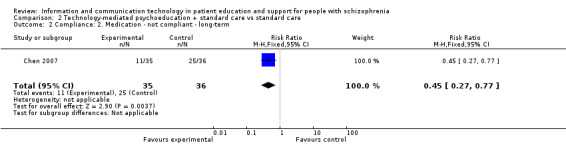

When technology‐mediated psychoeducation was used as an adjunct to standard care it did not improve general compliance in the short term (n = 291, 3 RCTs, RR for leaving the study early 0.81, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.19) or in the long term (n = 434, 2 RCTs, RR for leaving the study early 0.70, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.25). However, it did improve compliance with medication in the long term (n = 71, 1 RCT, RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.77). Adding technology‐mediated psychoeducation on top of standard care did not clearly improve either general mental state, negative or positive symptoms, global state, level of knowledge or quality of life. However, the results were not consistent regarding level of knowledge and satisfaction with treatment.

When technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care was compared with patient education not using technology the only outcome reported was satisfaction with treatment. There were no differences between groups.

Authors' conclusions

Using ICT to deliver psychoeducational interventions has no clear effects compared with standard care, other methods of delivering psychoeducation and support, or both. Researchers used a variety of methods of delivery and outcomes, and studies were few and underpowered. ICT remains a promising method of delivering psychoeducation; the equivocal findings of this review should not postpone high‐quality research in this area.

Keywords: Humans, Communication, Medical Informatics Applications, Patient Education as Topic, Patient Education as Topic/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/therapy

Plain language summary

Patient education and support for people with schizophrenia by using information and communication technology

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) includes the use of computers, telephones, television and radio, video and audio recordings. It consists of all technical means used to handle information and communication. During the last twenty years there has been a growing trend towards the use of ICT for the delivery of education, treatment and social support for people with mental illness.

Education about illness and treatment has been found to be a good way to increase a person's awareness of their health. ICT has the potential to improve many aspects of overall care, including: better education and social support; improved information and management of illness; increased access to health services; improved quality of care; better contact and continuity with services and cut costs. Recent studies show that ICT and the web may also support people in their working lives and social relationships plus help cope with depression and anxiety. However, there is a lack of knowledge about the specific effectiveness of ICT for helping people with severe mental health problems such as schizophrenia.

This review includes six studies with a total of 1063 people. Although education and support using ICT shows great promise, there was no clear benefit of using ICT (when compared with standard or usual care and/or other methods of education and support) for people with severe mental illness. However, the authors of the review suggest that this should not put off or postpone future high quality research on ICT, which is a promising and growing area of much importance.

This Plain Language Summary has been written by Benjamin Gray, Service User and Service User Expert, Rethink Mental Illness. Email: ben.gray@rethink.org

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation compared to standard care intervention for people with schizophrenia.

| Technology‐mediated psychoeducation compared to standard care intervention for people with schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with schizophrenia Settings: in and out‐patient psychiatric care unit and rehabilitation centres Intervention: technology‐mediated psychoeducation Comparison: standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard care intervention | Technology‐mediated psychoeducation | |||||

| Compliance/satisfaction: leaving the study early ‐ any reason Follow‐up: 52 weeks | Low1 | RR 1.24 (0.81 to 1.88) | 116 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 248 per 1000 (162 to 376) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 | 496 per 1000 (324 to 752) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 600 per 1000 | 744 per 1000 (486 to 1000) | |||||

| Mental state: not improved ‐ short‐term BPRS Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Low | RR 0.75 (0.56 to 1) | 84 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5,6 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 375 per 1000 (280 to 500) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 525 per 1000 (392 to 700) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 675 per 1000 (504 to 900) | |||||

| Global state: not improved ‐ short‐term GAF Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) | 84 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4,5 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 540 per 1000 (410 to 710) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 756 per 1000 (574 to 994) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 972 per 1000 (738 to 1000) | |||||

| Knowledge/insight | Moderate | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No trial reported this outcome. | |

| Quality of life | Moderate | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No trial reported this outcome. | |

| Needs | Moderate | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No trial reported this outcome. | |

| Social support Social Network Interview Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Low | RR 0.42 (0.04 to 0.80) | 60 (1 study) | |||

| 500 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (20 to 400) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (28 to 560) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 378 per 1000 (36 to 720) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CI: Confidence interval; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Middle control group risk approximates that in trial control group. 2 Limitation in design: rated 'serious' ‐ randomisation not described. 3 Indirectness: rated as 'serious' ‐ implication of not being compliant. 4 Publication bias: rated 'likely' ‐ outcome data incomplete. 5 Assumed those who discontinued would not change if had remained in study. 6 Publication bias: rated 'likely' ‐ small single trial.

Summary of findings 2. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care intervention compared to standard care intervention for people with schizophrenia.

| Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care intervention compared to standard care intervention for people with schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with schizophrenia Settings: in and out‐patient psychiatric care unit and rehabilitation centres Intervention: technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care intervention Comparison: standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard care intervention | Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care intervention | |||||

| Compliance/satisfaction: medication ‐ not compliant ‐ long‐term Follow‐up: 52 weeks | Low1 | RR 0.45 (0.27 to 0.77) | 71 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 225 per 1000 (135 to 385) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 315 per 1000 (189 to 539) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 405 per 1000 (243 to 693) | |||||

| Mental state: not improved ‐ short‐term BPRS Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 0.86 (0.63 to 1.19) | 56 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6,7 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 430 per 1000 (315 to 595) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 602 per 1000 (441 to 833) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 774 per 1000 (567 to 1000) | |||||

| Global state: not improved ‐ short‐term GAF Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 1.15 (0.86 to 1.54) | 56 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,7 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 575 per 1000 (430 to 770) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 805 per 1000 (602 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (774 to 1000) | |||||

| Knowledge/insight: not improved ITAQ Follow‐up: 12 weeks | Low1 | RR 1 (0.76 to 1.31) | 56 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,7 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 500 per 1000 (380 to 655) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 700 per 1000 (532 to 917) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 900 per 1000 (684 to 1000) | |||||

| Quality of life | Moderate | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No trial reported this outcome. | |

| Needs | Moderate | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No trial reported this outcome. | |

| Social support | Moderate | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No trial reported this outcome. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CI: Confidence interval; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Middle control group risk approximates that in trial control group. 2 Limitation in design: rated 'serious' ‐ randomisation not well described ‐ "Randomised participants matched (age, gender, length of illness, type of schizophrenia)" ‐ no further details. 3 Imprecision: rated as 'serious' ‐ small sample size. 4 Publication bias: rated as 'likely' ‐ small single trial. 5 Limitation in design: rated 'serious' ‐ randomisation not described. 6 Assumed those who discontinued would not change if had remained in study. 7 Publication bias: rated 'likely' ‐ outcome data incomplete.

Background

During the last two decades there has been a growing tendency towards the use of information and computer technology (ICT) in the delivery of treatments that support social relations of all citizens (European Commission 2001; Lewis 2003). ICT is increasingly used for range of purposes in business, government and health care (European Communities 2007). Globally, ICT has become an effective instrumement to communicate and increase awareness of mental health (Boyce 2011). The use of eHealth is particularly being supported by different EU agendas, most recently in the EU eGovernment action plan for the years 2011 to 2015 (European Commission 2010). There is, however, a lack of knowledge about effective ICT applications used in treatment delivery for people with schizophrenia (Podoll 2000).

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder with a lifetime prevalence of about 1%. For many people afflicted with the illness, schizophrenia results in chronic disabilities (Kaplan 2007). Currently, around 24 million people worldwide suffer from schizophrenia (WHO 2011). The illness is characterised by profound disruption in thinking, affecting language, perception and sense of self. It often includes psychotic experiences such as hearing voices or delusions. It can impair functioning through the loss of capability to earn one's own livelihood or the disruption of studies (WHO 2006). Defects of cognitive functions such as problem‐solving ability, explicit memory, knowledge and general intellectual capacities have been reported (Kaplan 2007).

Other problems disturbing daily life are a lack of insight (Morrison 2006), relapse (Haro 2006), non‐compliance with treatment (Freudenreich 2004; Kikkert 2006) and feelings of isolation and loneliness (Chan 2004; Morrison 2006). Schizophrenia is associated with mortality rates that are two to three times higher than those observed in the general population (Auquier 2007) and the risk for suicide is higher than in the general population (Hor 2010; Palmer 2005). In addition, schizophrenia is associated with poor quality of life (Bobes 2006; Evans 2007).

Treatment of schizophrenia varies based on the different phases of patient illness. In the acute, stabilisation or maintenance phase, antipsychotic medication is the mainstay of treatment, with the newer atypical antipsychotic agents often thought to be superior (Kaplan 2007; Turner 2006). Most people with schizophrenia benefit from the combined use of antipsychotic drugs and psychosocial therapies (Tandon 2006). Lack of compliance, however, can be a problem. Stable patients who are maintained on an antipsychotic have a much lower relapse rate than patients who have their medication discontinued. It has been suggested that 16 to 23 per cent of patients receiving treatment will experience a relapse within a year and 53 to 72 per cent will relapse without medication (Kaplan 2007). Other treatment methods besides medication are psychosocial therapies, which include a variety of methods to increase social abilities, self sufficiency, practical skills and interpersonal communication in patients with schizophrenia (Kaplan 2007). A range of psychosocial treatments are also helpful, including family intervention, supported employment, cognitive‐behaviour therapy for psychosis, social skills training or teaching illness self management skills (Mueser 2005). For example, behavioural skills training focusing on patients’ symptoms may include videotapes or homework assignments for the specific skills. It has been shown that social skills training, along with pharmacological therapy, can be supportive and useful for patients (Kaplan 2007). However, willingness to follow through with a treatment plan is often related to a person's perception and understanding of their illness, and amongst other issues that may contribute to poor compliance with medication, people with schizophrenia may lack this insight (Kikkert 2006; Perkins 2000).

Description of the intervention

ICT consists of all technical means used to handle information and communication. It can include computers, network hardware and software, telephones, broadcast media, and audio and video processing and transmission (International Telecommunication Union 2009). ICT applications in health care can vary, and they can include telephones, mobile phones, computers, Internet, electronic databases and decision‐support systems. In recent years, a concept of eHealth has also increasingly been used to refer to ICT applications (Eysenbach 2001). eHealth, in turn, has been defined as the application of ICT across the whole range of functions that affect health care, from diagnosis to follow‐up (Silber 2003). It also refers to the use of modern information and communication technologies to meet the needs of citizens, patients, healthcare professionals and healthcare providers, as well as policymakers (Ministerial Declaration 2003).

eHealth can be defined as encompassing ICT‐enabled solutions providing benefits to health, be it at the individual or at the societal level (European Communities 2007). In a systematic review of published definitions of eHealth researchers found no clear consensus about the meaning of the term eHealth. They identified two universal themes (health and technology) and six less general themes (commerce, activities, stakeholders, outcomes, place and perspectives) (Oh 2005). E‐mental health can be understood as the use of digital technologies and new media for the delivery of screening, health promotion, prevention, early intervention, treatment or relapse prevention, as well as for improvement of health care delivery, e‐learning and online research in the field of mental health (Riper 2010).

How the intervention might work

Education about illness and treatment has been found to be an effective way to increase a person's awareness of their mental health problems (Gumley 2006; Perry 1999; Turkington 2002). Such increased awareness can lead to increased treatment compliance with consequent reduction of relapse, or readmission rates (Xia 2011). Education may also help people to evaluate their mood, self esteem and negative beliefs about themselves and others, which are to be considered when designing interventions (Smith 2006). In addition, clinical interventions that foster appraisals of recovery may improve emotional well‐being in people with psychosis (Watson 2006).

Use of ICT applications for patient education and support has the potential to improve information management, access to health services, quality of care, continuity of services and cost containment. In addition, they have the added benefit that many people turn to 'the web' to obtain information because of its anonymity and the fear of stigmatisation often associated with consulting mental heath professionals is reduced (Eysenbach 2001). Recent studies indicate that the Internet has shown promise in patient education, providing different methods to illustrate the educational material. Results show that computer‐delivered interventions could improve outcomes for a wide range of common mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, work, social adjustment or general psychopathology in the general public (Christensen 2002; Proudfoot 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite a considerable increase in the use of ICT‐based approaches in mental health services, its effect on people with schizophrenia has been less systematically evaluated (Podoll 2000; Walker 2006). Indeed, ICT methods used by patient groups who show poor compliance have received considerably less attention, despite being able to recruit well and maintain their participation (Jones 2001b). To avoid alienation of those with mental illness from the information society, a systematic evaluation of the effects of ICT in daily clinical practice for mental health services is needed.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of using information and communication technology (ICT) as a means of educating and supporting people with schizophrenia or related psychoses compared to standard care, other methods of delivering psychoeducation and support, or both.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, for example, with alternation as the method of randomisation.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychoses (schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders). We included trials where it was implied that the majority of participants had a severe mental illness which was likely to be schizophrenia, including those with multiple diagnoses as well, and did not exclude trials due to age, nationality, gender, duration of illness or treatment setting.

Types of interventions

1. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation

Psychoeducation and support using ICT as sole method of delivery of treatment. ICT applications are varied and can include telehealth, telephones, mobile phones, computers and the Internet. These interventions can be provided by a single person with the main purpose of maintaining current functioning or assisting coping abilities in people who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like illness. The therapies can be aimed at individuals or groups of people. If the content of the therapy was not sufficiently clear after reading a clinical study, then we included any therapy that had supportive or support in its title. The intervention had to go beyond the provision of or access to an ICT application; there should be a planned strategy for ICT use.

We planned to classify ICT systems for the purposes of this review into broad categories, taking into consideration ease of access (mobile phones (high access), Internet, personal computer program (lower access)) and the complexity of the interface (simple, with minimal requirements expected from user, through to complex, with the need to enter complex data). However, we did not undertake this categorisation due to the low number of trials found.

2. ICT combination: technology‐mediated psychoeducation and standard care

Psychoeducation and support using ICT combined with standard care. Standard care is defined as the care a person would normally receive if they had not been included in the research trial. This would include interventions provided by health care professionals such as medication, hospitalisation, community psychiatric nursing input and/or day hospital but should explicitly state that formalised psychoeducation and support is not part of this package.

3. Psychoeducation with no technology

Psychoeducation intervention using only including supportive treatment (biological, psychological or social) such as problem‐solving therapy, psychoeducation, social skills training, cognitive‐behavioural therapy, family therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy.

4. Standard care

Standard care or 'no' intervention is defined as the care a person would normally receive if they had not been included in the research trial. This would include interventions provided by health care professionals such as medication, hospitalisation, community psychiatric nursing input and/or day hospital but should explicitly state that formalised psychoeducation and support is not part of this package.

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes into short‐term (up to 12 weeks), medium‐term (13 to 26 weeks) and long‐term (over 26 weeks).

Primary outcomes

1. Patient compliance

1.1 Compliance with treatment and medication

2. Global state

2.1 Relapse (both incidence of and time to relapse) 2.2 No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies)

Secondary outcomes

1. Patient compliance

1.1 Compliance with follow‐up 1.2 Leaving the study early

2. Mental state

2.1 No clinically important change in general mental state 2.2 Average endpoint general mental state score 2.3 Average change in general mental state scores 2.4 No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, mania) 2.5 Average endpoint specific symptom score 2.6 Average change in specific symptom scores

3. Global state

3.1 Average endpoint global state score 3.2 Average change in global state scores

4. Level of knowledge/insight

4.1 No clinically important change in average of understanding of his/her illness and need for treatment 4.2 Average endpoint understanding/knowledge of illness scores 4.3 Average change in understanding/knowledge of illness scores 4.4 Average endpoint understanding/knowledge of treatment and medication effect scores 4.5 Average change in understanding/knowledge of treatment and medication effect scores

5. Behaviour

5.1 No clinically important change in general behaviour 5.2 Average endpoint general behaviour score 5.3 Average change in general behaviour scores 5.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 5.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 5.6 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

6. Quality of life

6.1 No clinically important change in quality of life 6.2 Average endpoint quality of life score 6.3 Average change in quality of life scores 6.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 6.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 6.6 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life 6.7 Social support*

7. Satisfaction with treatment

7.1 Leaving the studies early 7.2 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 7.3 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 7.4 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 7.5 Carer not satisfied with treatment 7.6 Carer average satisfaction score 7.7 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

8. Health and social needs*

9. Service utilisation

9.1 Hospitalisation 9.2 Time to hospitalisation 9.3 Duration of stay in hospital

10. Health economic outcomes

10.1 Direct treatment costs 10.2 Indirect treatment costs

11. Death

11.1 Suicide 11.2 Natural causes

*Additional outcome added for since publication of protocol. Please see Differences between protocol and review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (June 2008, June 2009 and September 2010) using the phrase:

[((*communic* or *information* in title) or *computer* or *technolog* or * tele* or *phone* or *internet* or *digital* or *electronic* or *database* in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE) or (*computer* or tele* or *internet* or *technolog* or *electronic* in interventions of STUDY)].

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of journals and conference proceedings (see Cochrane Schizophrenia Group module).

Searching other resources

Reference searching

We inspected reference lists of identified studies for more relevant trials.

Personal contact

We contacted authors of relevant studies for inclusion to identify further relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors read the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and acquired training by attending relevant courses and workshops.

Selection of studies

Review authors (MV, HH, LK) inspected all abstracts of studies identified as above and suggested potentially relevant reports. Where disagreement occurred we resolved it by discussion, or where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, MV and HH inspected all full reports and independently decided whether they met inclusion criteria (i.e. Criteria for considering studies for this review). MV and HH were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions or journal of publication. Where difficulties or disputes arose, we asked authors CA, LK and ML for help; if it was impossible to decide, we added these studies to those ‘Characteristics of studies awaiting classification’ table and we contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

MV, HH and LK extracted data from all included studies. Again, we discussed any disagreement, documented decisions and, if necessary, contacted authors of studies for clarification. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but we only included if two authors independently had the same result. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter these data but added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment. We made attempts to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. With remaining problems ML and CA helped clarify issues and we documented those final decisions.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if:

a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b) the measuring instrument was not written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial; and c) the measuring instrument is either i. a self report or ii. completed by an independent rater.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint); normally both sets of data would be available to trialists but if change scores are presented, the SD of the change is often not provided. We decided to primarily use endpoint data and only use change data if the former were not available. Endpoint and change data were combined in the analysis as we used mean differences rather than standardised mean differences throughout (Higgins 2011, chapter 9.4.5.2).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion:

a) standard deviations and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996); c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS, which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and endpoint and these rules can be applied. Skewed endpoint data from studies of less than 200 participants were entered in additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data of means pose less of a problem if the sample size is large; if this condition was met, then skewed endpoint data were entered into syntheses.

When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not and we entered such data into analysis.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as length for course of illness (mean months per year).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

We did not convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. Thus, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

We entered data for unfavourable outcomes in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for ICT. Where the outcomes were favourable, the area to the right of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for ICT.

2.8 'Summary of findings' tables

We included the following short, medium or long‐term outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table and one global and, preferably binary, measure of each.

1. Compliance 2. Mental state 3. Global state 4. Knowledge/insight 5. Quality of life 6. Needs 7. Social support

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors (MV, HH, ML, LK, CEA) worked independently by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This new set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain additional information.

We have noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the Table 1.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data ‘yes/no’ ‐ data

We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the random‐effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios which tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we also presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we used only data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not present these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up data must lose credibility (Xia 2007). For any particular outcome if more than 40% of data was unaccounted for, we did not present these data or use them within analyses.

2. Last observation carried forward

We preferred not to make any assumptions about loss to follow‐up for continuous data and analysed results for those who completed the trial, since the use of methods such as the last observation carried forward (LOCF) introduce uncertainty about the reliability of the result (Leucht 2007). If LOCF data had been used in included trials, we reproduced these data and indicated that they were the result of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying situations or people which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, these were fully discussed.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose these were fully discussed.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3. 1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected the forest plots to evaluate the possibility of heterogeneity of intervention effects across trials as evidenced by outlying trials with non‐overlapping confidence intervals. We also noted differences in the direction of effect estimates across trials.

3.2 Employing I2 statistics

We considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. Then visual inspection of graphs was used to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented using, primarily, the I2 statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I2 estimate was greater than or equal to 50%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). If inconsistency was high, we did not summate data, but presented the data separately and investigated the reasons for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We attempted to locate protocols of included trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. Therefore, we chose the fixed‐effect model for all analyses. The reader is, however, able to choose to inspect the data using the random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We planned sensitivity analyses when a trial was described as double‐blind, but it was implied that the study was randomised. The included trials were not described as double‐blind with implied randomisation and therefore we did not need to perform sensitivity analyses.

2. Assumption for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data) we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. If there was a substantial difference, we reported these results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Chinese studies

Concerns were raised about the quality of the Chinese trials (Hu 2011; Wu 2009). For this reason we performed sensitivity analysis for all primary outcomes in which Chinese trials were included.

4. Requirements of the interventions

Focusing solely on primary outcomes we also aimed to investigate whether interventions falling into pre‐defined categories (i) highly accessible and simple requirements; ii) less widely accessible and requirements that cannot be described as simple; iii) access by specific interface with complex requirements) were suggested to have different effects. However, due to the limited data we did not perform sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

For more detailed description of each study, please see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

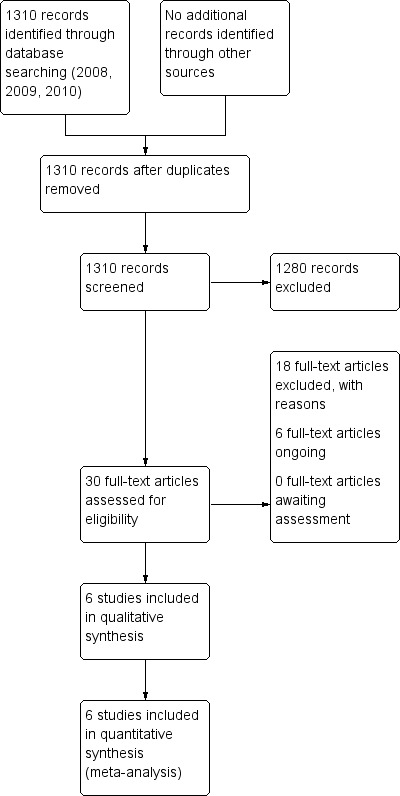

We undertook the first search in June 2008 and re‐ran it in 2009 and 2010 (see Appendix 1). In 2008 we identified 505 studies. In 2009, the search offered us 574 new references (from 293 studies) and in September 2010, we found 231 new references (from 191 studies). Thus, altogether the search totalled 1310 studies to be inspected for possible selection. The review now contains six included studies, 18 studies are excluded and six are ongoing studies that may be relevant to this review (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

This review includes six studies published between 2001 and 2010 (Chen 2007; Hansson 2008; Jones 2001b; Rotondi 2005; Salzer 2004; Valimaki 2010).

1. Methods

All studies were stated to be randomised, although description of the allocation varied. Randomisation was undertaken once people were matched (age, gender, length of illness and type of schizophrenia) in the Chen 2007 study. Hansson 2008 cluster‐randomised key workers. For further details please see the section below on Allocation (selection bias) and Blinding (performance bias and detection bias).

2. Study duration

Overall, the length of the trials varied although a majority used long‐term outcomes (over 26 weeks). Salzer 2004 followed people up to 13 months and three other studies up to 12 months (Chen 2007; Hansson 2008; Valimaki 2010). The length of the other two trials was six (Rotondi 2005) and three months (Jones 2001b).

3. Design

All of the six studies used a parallel study design. However, one employed a cluster technique (cluster by key worker, Hansson 2008). In this study over 500 participants took part but there were 134 clusters. The paper does not report intra class correlation coefficients (ICC) but we have had direct contact with the authors of the trial and they are aware of the importance of this statistic. They will forward these data when available. For this version of the review, however, we have had to assume the ICC to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). This results in a design effect of 1.28 for the intervention group and 1.20 for the control.

4. Participants

Participants totalled 1063 people with schizophrenia from the six trials between the years 2001 to 2010. Rotondi 2005 specified participants’ diagnosis as "schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder" while Salzer 2004 used "schizophrenia‐spectrum". Diagnoses were based on different operationalised criteria such as ICD‐10 (Hansson 2008; Jones 2001b; Valimaki 2010), CCMD‐3 (Chen 2007) or DSM‐IV (Salzer 2004).

In three trials, participants were aged between 18 and 65 years (Hansson 2008; Jones 2001b; Valimaki 2010). Chen 2007 included some younger people (range 15 to 65 years). Rotondi 2005 reported age by mean (37.5 years) and Salzer 2004 did not report information about age.

Patients were in different states of illness. Chen 2007 reported that the mean length of patient illness was 10 years, while in Hansson 2008 study patients' duration of illness was about 16 years. The mean number of hospital admissions was about five in Hansson 2008. In the Valimaki 2010 study, patients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals and the mean length of their hospital stay was 60 days. In two studies patients were excluded if they had severe organic psychiatric illness (Hansson 2008) of if patients were acutely ill (Jones 2001b). On the other hand, Rotondi 2005 excluded patients if they had not had hospitalisation within the previous two years. In one study (Salzer 2004) patients' illness history was not described in detail.

5. Setting

Out of all six trials, 30 patients were treated in both in‐ and out‐patient settings (Rotondi 2005), 311 patients were recruited in an in‐patient setting (Valimaki 2010) and the rest (722 people) were treated in different types of out‐patient settings.

6. Study size

Overall, study size varied from 30 (Rotondi 2005) to 507 (Hansson 2008) patients, although in the largest trial participants were within 134 clusters.

7. Interventions

7.1 Intervention group

All psychoeducation or patient support interventions were included. Interventions used in the trials, however, varied considerably. We excluded staff support systems.

Chen 2007 used technology‐mediated psychoeducation and a standardised nursing intervention. ICT involved digital and spot network group and psychological online consultation.

In Hansson 2008, clinicians, in addition to continuing with standard treatment, implemented the manualised intervention 'DIALOG'. This is a computer‐mediated procedure to discuss quality of life domains with patients. Answers to all questions were entered directly onto a hand‐held computer or laptop using software specifically developed for the study. The intervention was repeated every two months so that participants' views on their situation and needs for care were explicit (Hansson 2008).

The Jones 2001a study involved five educational sessions using a computer intervention. In a ‘computer only’ group, patients were shown how to use the computer by a researcher. Three different types of screen display were used: general information, personal information from the viewing patient’s medical record with general information and questionnaires including medical record audit plus feedback displays. At the end of the session, participants received feedback information if requested (Jones 2001b).

Rotondi 2005 used the Schizophrenia Guide website as a telehealth intervention. The programme collected information on each participant’s usage of the website. The Schizophrenia Guide provided three online therapy groups; the ability to ask questions of the experts associated with the project and receive an answer; a library of previous asked and answered questions; activities in the community and news items that focus on mental health issues; and educational reading materials (Rotondi 2005).

Salzer 2004 employed a brief telephone‐based medication management programme (TMM) to enhance communication, insight, attitudes, knowledge and satisfaction among patients in weekly programme (altogether 52 weeks).

Lastly Valimaki 2010 used an IT‐based patient education programme to support well‐being. The programme offered need‐based computerised information and discussions with staff in five sessions, plus printed material based on patients' requests. This involved a total of five sessions for each participant.

7.2 Comparison group

There were also different comparison groups for each of the six studies. Chen 2007 used "general rehabilitation treatment" as standardised care. The Hansson 2008 control used key worker as "treatment as usual". Rotondi 2005 and Salzer 2004 both used "general treatment" as control. The Jones 2001a control involved a standardised nursing intervention as the comparison group. This was "community psychiatric nurse only" in which the hour‐long session with the community psychiatric nurse covered the same content as the computer system. Participants could also receive a printed summary. In addition, "combination of community psychiatric nurse and computer", which combined a first session offered by community nurse, sessions two to four by computer and the last session again with the nurse. In addition, patients were given relevant printed summaries from sessions. Finally Valimaki 2010 used a "standardised nursing intervention" as comparison group. In this case "traditional patient education" included five patient education sessions with printed leaflets for each participant.

8. Outcomes

8.1 General

The duration of follow‐up in the included trials varied between three and 12 months. Details of the scales used in this review to quantify different outcomes are provided below. Data from these scales were reported either in continuous form or as binary figures.

8.2 Binary data

8.2.1 Leaving the study early

All studies used a measure of whether a patient left the study early. In this review we assumed that if they were not included in analysis these people left early.

8.2.2 Drug compliance

In one study drug compliance was measured by counting payments for medication (Chen 2007).

8.3 Scales

8.3.1 Mental state scales

8.3.1.1 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1987) This is a 30‐item scale, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system from absent to extreme. There are three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P) and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity. Two studies reported data from this scale.

8.3.1.2 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) is an 18‐item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐tem scale is commonly used. Scores can be ranged from 0 to 126. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale varying from ‘not presented’ to ‘extremely severe’, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. One study reported data from this scale.

8.3.1.3 Perceived stress ‐ Psychological distress (Zautra 1988) This is a scale including six sub‐scales: anxiety/dread (10 items), helplessness/hopelessness (four items) and confused thinking (two items), anxiety (seven items), suicidal ideation (three items) and depression (10 items). A high score indicates higher stress. One study reported data from this scale.

8.3.2 Global state scales

8.3.2.1 Global Assessment of Functioning ‐ GAF (APA 1994a) GAF is a global measure covering the range from positive mental health to severe psychopathology. It measures the degree of mental illness by rating psychological, social and occupational functioning. The 100‐point scales are divided into intervals each with 10 points. The 10‐point intervals have anchor points describing symptoms and functioning that are relevant for scoring. The anchor points for interval 1 to 10 describe the most severely ill and the anchor points for interval 91 to 100 describe the healthiest.

8.3.2.2 Social Disability Screening Schedule – SDSS (Cooper 1996; Shen 1985) The SDSS has been designed to yield continuous ratings of severity of substance dependence in compatibility with DSM‐IV and ICD‐10. High scores indicate poor outcome. One study reported data from this scale.

8.3.4 Knowledge/insight scales

8.3.4.1 Knowledge and Information about Schizophrenia Schedule ‐ KISS (Barrowclough 1987; Jones 2001a) KISS is a structured interview measuring the knowledge and information about schizophrenia schedule (KISS), which was developed for the pilot study partly on the basis of the KASI used for carers (Barrowclough 1987; Jones 2001a). One study reported data from this scale.

8.5.2 Insight and Treatment Attitude Questionnaire – ITAQ (McEvoy 1989) The ITAQ is an 11‐item semi‐structured interview that measures awareness of illness and attitude to medication and services, as well as follow‐up evaluation. Its scores range from 0 to 22, with a high score indicating better insight. One study reported data from the scale.

8.3.5 Quality of life scales

8.3.5.1 Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life ‐ MANSA (Slade 2005) This 16‐item measure comprises objective and subjective questions. Each item is rated on a seven‐point satisfaction scale, from 1 = ‘Couldn't be worse’ to 7 = ‘Couldn't be better’. The higher score indicates the better quality of life. One study reported data from the scale.

8.3.6 Satisfaction with treatment

8.3.6.1 The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire‐8 ‐ CSQ‐8 (Larsen 1979) CSQ‐8 is a self report statement of satisfaction with health and human services. The scale includes eight items with a four‐point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 8 to 32. A higher score indicates higher satisfaction (Larsen 1979). One study reported data from the scale.

8.3.6.2. Patient Satisfaction Scale ‐ PSS‐Fin PSS‐Fin is a Finnish adaptation of the Patient Satisfaction Scale (PSS, Kuosmanen 2009; Suhonen 2007). It includes 10 items in three sub‐scales (technical‐scientific, informational and interaction/support care needs). The answer format is a four‐point Likert‐type scale (1 = very dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = satisfied, 4 = very satisfied). The PSS‐Fin has demonstrated good psychometric properties and conceptual rigour when used with surgical patients (Suhonen 2007). It has been used in a study with schizophrenia patients, but with no reliability testing (Kuosmanen 2009). A higher score indicates higher satisfaction. One study reported data from the scale.

8.3.7 Needs scales

8.3.7.1 Camberwell Assessment of Need ‐ Short Appraisal Schedule; patient‐rated version – CANSAS (Slade 2005) The Camberwell Assessment of Need ‐ Short Appraisal Schedule assesses health and social needs across 22 domains. The schedule summarises whether a person with mental health problems has difficulties in 22 different areas of life, and whether they are currently receiving any effective help with these difficulties. For each domain it distinguishes between ‘no need' (rating of 0), ‘met need’ (rating of 1) and ‘unmet need' (rating of 2). A higher score indicates higher unmet needs. One study reported data from the scale.

8.3.8 Social support scales

8.3.8.1 Social Network Interview (Fischer 1982; McCallister 1978; Zautra 1984) The Social Network Interview assess social network characteristics using an abridged 14‐item version of a scale. Ten items on this scale ask subjects to identify people who provide various types of instrumental social support (e.g. financial assistance or help with shopping or errands) and emotional social support (e.g. whom they confided in, discussed personal worries with, relied on for advice). The remaining four items ask subjects to identify individuals who are the sources of negative social experiences. Probes ask respondents to name individuals who cause problems by criticising the subject's behaviour, breaking promises to the subject, or consistently provoking feelings of anger.

8.4 Missing outcomes

One trial reported on our primary outcome compliance with medication (Chen 2007) and two trials reported on our primary outcome global state (Chen 2007; Jones 2001a). Data on compliance with medication from two trials could not be used (Salzer 2004; Valimaki 2010) and data on global state could not be used in two trials (Jones 2001a; Valimaki 2010). All six included studies reported compliance with intervention in terms of leaving the study early (Chen 2007; Hansson 2008; Jones 2001b, Rotondi 2005; Salzer 2004; Valimaki 2010). However, there were no data on behaviour, service utilisation, economic outcomes or mortality.

Excluded studies

We excluded 18 studies. Han 2008 and Shon 2002 had to be excluded because they were not randomised. We also excluded nine studies because they employed an intervention not appropriate for this review (Burgoyne 1983; Fan 2005; Frangou 2005; Kopelowicz 2006; Montes 2009; Park 2009; Pijnenborg 2010; Rossi 1994; Yi 2006). A further two studies were excluded because no data were usable due to the lack of presentation of means or standard deviations (Berns 2001; Borell 1995). Finally, we could not included five trials because the majority of participants were not people with schizophrenia (Cramer 1999; Crespo 2006; Janssen 2010; Kluger 1983; MacDonald 2000).

Studies awaiting assessment

No studies are awaiting assessment.

Ongoing studies

Six studies are ongoing (Hulsbosch 2008; Jahn 2008; Potts 2008; Prague 2008; Weisbrod 2007; Young 2009). These trials were started between 2006 and 2011 and should be completed between 2009 and 2013. We currently have no information on the results of these trials.

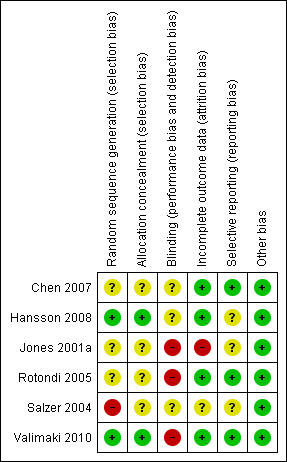

Risk of bias in included studies

Our overall impression of risk of bias in the included studies is represented in Figure 2. The suggestion is that there is a moderate risk of bias and therefore a risk of overestimating any positive effects of ICT use in psychoeducation or patient support.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

No study implied randomisation ‐ all clearly stated that randomisation took place. Therefore we have not undertaken any sensitivity analysis regarding this.

Allocation

All six studies were stated to be randomised but only two trials were clear about the means of allocation (Hansson 2008; Valimaki 2010). Three studies were not explicit about how allocation was achieved other than using the word "randomised" and therefore we categorised them as ‘unclear’ (Chen 2007; Jones 2001b; Rotondi 2005). One study randomly allocated participants matching age, length of illness and type of schizophrenia. However, sequence generation and allocation concealment was unclear (Salzer 2004).

Blinding

Three out of six studies reported that no form of blinding had been used (Jones 2001b; Rotondi 2005; Valimaki 2010). The remaining three studies did not report whether blinding had been used. Therefore we had to rate the risk of observed bias as (at best) ‘unclear’. This gathers further potential for overestimation of positive effects and underestimation of negative ones.

Incomplete outcome data

We considered four out of the six studies as reporting incomplete outcome data. Study attrition, however, was often not reported clearly and therefore trials may have used the technique of carrying forward the last observation of participants. This has introduced some more uncertainty into the results. It is unlikely that participants who left the studies early remained stable ‐ the assumption employed in the last observation carried forward technique.

When attrition rate was reported it varied between 11% (Hansson 2008) and 40% (Jones 2001a). In Jones 2001a high loss to follow‐up is a clear threat to the validity of findings. We took this into account when we interpreted the results of the review. Rotondi 2005 reported that there was no loss to follow‐up.

Selective reporting

The majority of data in this review originate from published reports. We have had no opportunity to see protocols for these trials to compare the outcomes reported in the full publications with what was measured during the conduct of the trial. We considered all included trials to be free of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered all six included studies to be free of other potential sources of bias. One Chinese trial (Chen 2007) was included. Strong and depressing evidence has emerged that many trials from the People's Republic of China which are stated to be randomised are not (Wu 2006). At this point we have not contacted the authors to verify the process by which they randomised. We will try to amend this situation for future versions of this review.

Effects of interventions

1. Comparison 1. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation versus standard care

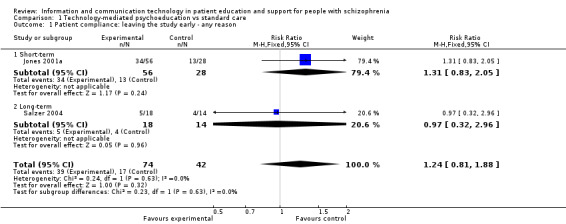

1.1 Patient compliance: leaving the study early ‐ any reason

We found one study reporting short‐term and one reporting long‐term compliance with the intervention. Overall, there was no difference between groups (n = 116, two randomised controlled trials (RCTs), risk ratio (RR) 1.24, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.88, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation vs standard care, Outcome 1 Patient compliance: leaving the study early ‐ any reason.

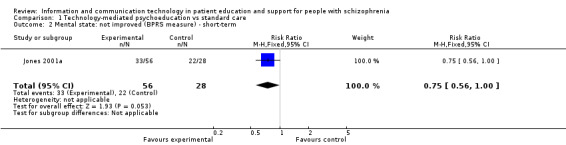

1.2 Mental state

1.2.1 Not improved (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) measure) ‐ short‐term

One study reported mental state as a binary outcome (not improved). Fewer people allocated to technology‐mediated psychoeducation did not improve compared with those allocated to the standard care group (n = 84, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.00, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation vs standard care, Outcome 2 Mental state: not improved (BPRS measure) ‐ short‐term.

1.2.2 Average score (Perceived stress ‐ Psychological distress measure, high = good) ‐ short‐term

One small study reported mental state as a continuous outcome. Short‐term outcome favoured technology‐mediated psychoeducation (n = 30, mean difference (MD) ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.90 to ‐0.12, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation vs standard care, Outcome 3 Mental state: average score (Perceived stress ‐ Psychological distress measure, high = bad) ‐ short‐term.

1.3 Global state: not improved (Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) measure) ‐ short‐term

One study reported global state as a binary outcome. There was no difference between groups (n = 84, RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.42, Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation vs standard care, Outcome 4 Global state: not improved (GAF measure) ‐ short‐term.

1.4 Knowledge and insight: not improved ‐ short‐term

Knowledge and insight were measured as two binary outcomes in one study. We found no difference between groups (n = 84, Insight and Treatment Attitude Questionnaire (ITAQ): RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.15, Knowledge and Information about Schizophrenia Schedule (KISS): RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.03, Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation vs standard care, Outcome 5 Knowledge and insight: not improved ‐ short‐term.

1.5 Social support: average score (Social Network Interview, high = good) ‐ short‐term

People allocated to technology‐mediated psychoeducation perceived that they received more social support than people allocated to the standard care group (n = 30, 1 RCT, MD 0.42, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.80, Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation vs standard care, Outcome 6 Social support: average score (Social Network Interview, high = good) ‐ short‐term.

2. Comparison 2. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care versus standard care

2.1 Compliance

2.1.2 General ‐ leaving the study early ‐ any reason

We found five studies reporting compliance with the intervention. There was no difference between groups in the short term (n = 291, 3 RCTs, RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.19) or in the long term (n = 434, 2 RCTs, RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.25, Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 1 Compliance: 1. General ‐ leaving the study early ‐ any reason.

2.1.2 Medication ‐ not compliant ‐ long‐term

One study reported compliance with medication. People allocated to technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care intervention were more compliant with medication than people allocated to the standard care group (n = 71, RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.77, Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 2 Compliance: 2. Medication ‐ not compliant ‐ long‐term.

2.2 Mental state

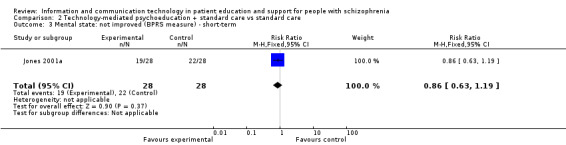

2.2.1 Not improved (BPRS measure) ‐ short‐term

We found one small study reporting mental state as a binary outcome (not improved). There was no difference between groups (n = 56, RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.19, Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 3 Mental state: not improved (BPRS measure) ‐ short‐term.

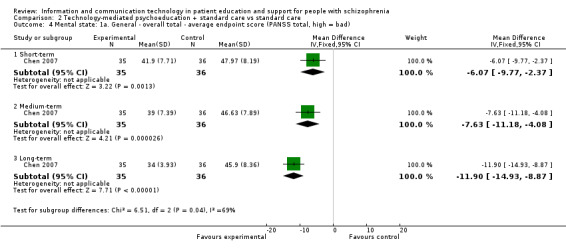

2.2.2 General ‐ overall total ‐ average endpoint score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total, high = bad)

Mental state was measured with total score in one study with 71 participants. There were significant differences favouring the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care intervention in the short term (MD ‐6.07, 95% CI ‐9.77 to ‐2.37), in the medium term (MD ‐7.63, 95% CI ‐11.18 to ‐4.08) and in the long term (MD ‐11.90, 95% CI 14.93 to ‐8.87, Analysis 2.4)

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 4 Mental state: 1a. General ‐ overall total ‐ average endpoint score (PANSS total, high = bad).

2.2.3 Mental state: 1b. General ‐ general symptoms sub‐score ‐ average endpoint (PANSS sub‐scale, high = bad) ‐ long‐term

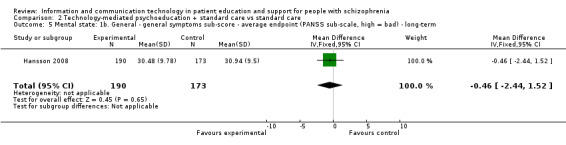

One study measured mental state with general symptoms sub‐score in the long term. We found no difference between groups (n = 363, MD ‐0.46, 95% CI ‐2.44 to 1.52, Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 5 Mental state: 1b. General ‐ general symptoms sub‐score ‐ average endpoint (PANSS sub‐scale, high = bad) ‐ long‐term.

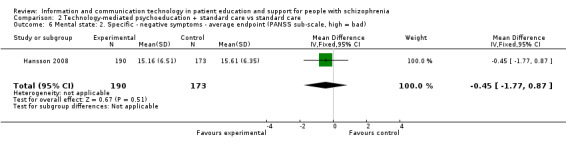

2.2.4 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ negative symptoms ‐ average endpoint (PANSS sub‐scale, high = bad)

One study reported mental state measured with negative symptoms sub‐score in the long term. There was no difference between groups (n = 363, MD ‐0.45, 95% CI ‐1.77 to 0.87, Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 6 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ negative symptoms ‐ average endpoint (PANSS sub‐scale, high = bad).

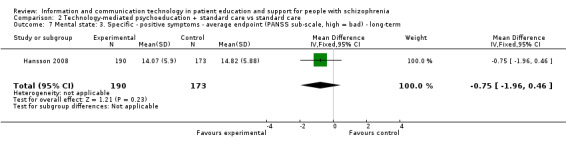

2.2.5 Mental state: 3. Specific ‐ positive symptoms ‐ average endpoint (PANSS sub‐scale, high = bad) ‐ long‐term

One study reported mental state measured as positive symptoms sub‐score in the long term. We found no difference between groups (n = 363, MD ‐0.75, 95% CI ‐1.96 to 0.46, Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 7 Mental state: 3. Specific ‐ positive symptoms ‐ average endpoint (PANSS sub‐scale, high = bad) ‐ long‐term.

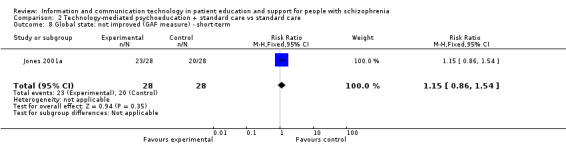

2.3 Global state

2.3.1 Not improved (GAF measure) ‐ short‐term

There was no difference between groups (n = 56, 1 RCT, RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.54, Analysis 2.8).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 8 Global state: not improved (GAF measure) ‐ short‐term.

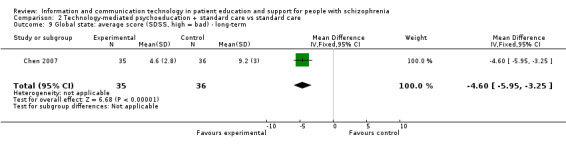

2.3.2 Average score (Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS), high = bad) ‐ long‐term

Global state among people allocated to the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care group improved more than among people allocated to the standard care group (n = 71, 1 RCT, MD ‐4.60, 95% CI ‐5.95 to ‐3.25, Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 9 Global state: average score (SDSS, high = bad) ‐ long‐term.

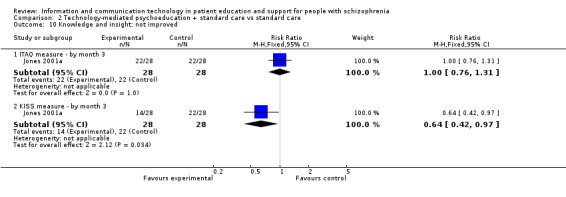

2.4 Knowledge and insight: not improved

Knowledge and insight were measured with two binary outcomes in one study. We found no difference between groups measured with ITAQ (n = 56, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.31). However, when knowledge by month three was measured with KISS, fewer people allocated to the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care group did not improve compared with those allocated to the standard care group (n = 56, RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.97, Analysis 2.10).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 10 Knowledge and insight: not improved.

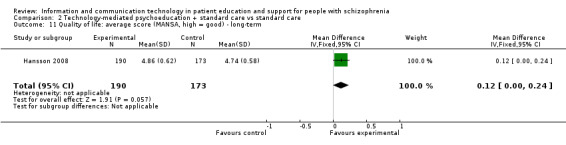

2.5 Quality of life: average score (Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA), high = bad) ‐ long‐term

We found no difference between groups in quality of life (n = 363, 1 RCT, MD 0.12, 95% CI ‐0.00 to 0.24, Analysis 2.11).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 11 Quality of life: average score (MANSA, high = good) ‐ long‐term.

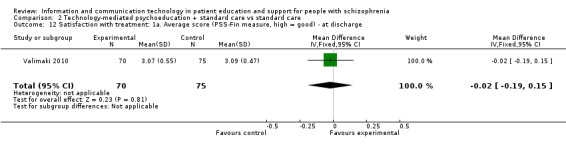

2.6 Satisfaction with treatment

2.6.1 Average score (Patient Satisfaction Scale (PSS‐Fin) measure, high = good) ‐ at discharge

We found no difference between groups in satisfaction with treatment at discharge (n = 145, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.15, Analysis 2.12).

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 12 Satisfaction with treatment: 1a. Average score (PSS‐Fin measure, high = good) ‐ at discharge.

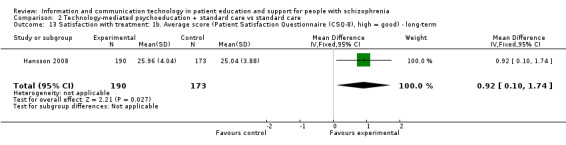

2.6.2 Average score (Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ‐8), high = good) ‐ long‐term

One study reported patient satisfaction with treatment. Long‐term outcome favoured technology‐mediated psychoeducation (n = 363, MD 0.92, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.74, Analysis 2.13).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 13 Satisfaction with treatment: 1b. Average score (Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ‐8), high = good) ‐ long‐term.

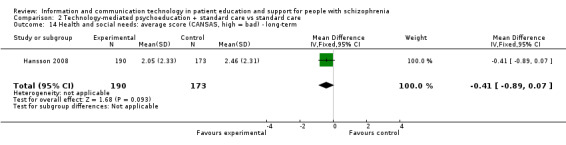

2.7 Needs: average score (Camberwell Assessment of Need ‐ Short Appraisal Schedule (CANSAS), high = bad) ‐ long‐term

We found no difference between groups (n = 363, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐0.89 to 0.07, Analysis 2.14).

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs standard care, Outcome 14 Health and social needs: average score (CANSAS, high = bad) ‐ long‐term.

2.8 Sensitivity analysis

Data from Chen 2007 were included in the primary outcome of 'compliance' (Analysis 2.1). This is by far the smallest of the two studies in this subgroup (long‐term) and removal of these data makes no substantive difference to the direction or precision of the result (n = 434, 2 RCTs, RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.25 versus 1 RCT, n = 363, RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.46).

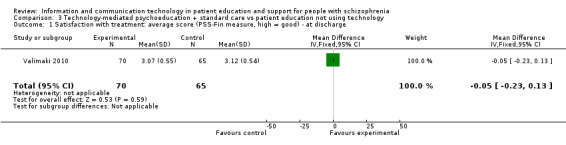

3. Comparison 3. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standar care intervention versus patient education not using technology

3.1 Satisfaction with treatment: average score (PSS‐Fin measure, high = good) ‐ at discharge

We found no difference between groups in satisfaction with treatment at discharge (n = 135, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.13, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Technology‐mediated psychoeducation + standard care vs patient education not using technology, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with treatment: average score (PSS‐Fin measure, high = good) ‐ at discharge.

Discussion

Summary of main results

1. Comparison 1. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation versus standard care intervention

Three studies with a total of 146 participants fell into this comparison.

1.1 Patient compliance

The overall rate of participants leaving the studies early was high (48%). There was no difference between groups. However, this finding was based on only two trials, limiting any interpretation but, nevertheless, such high attrition should be avoidable though empathetic study design ‐ or if it is not avoidable this then reflects badly on the acceptability of the trial and, perhaps, the applicability of the findings.

1.2 Mental state ‐ short‐term

Two different outcome measures revealed that technology‐mediated psychoeducation might improve mental state more than a standard care intervention. This is encouraging but the result must be interpreted with great caution as it was based on two small trials (total n = 114) reporting in different ways. More data are needed.

1.3 Global state

One trial reported no significant difference in effect on global state between interventions. This is not a difficult outcome to record and should have been feasible for all three trials.

1.4 Knowledge and insight

Jones 2001a used two different measures of knowledge and insight. The trial found no clear effect of technology‐mediated psychoeducation but the study was small (n = 84) and may have been underpowered. As with other outcomes, there is more work to be done.

1.5 Quality of life

No trial reported quality of life outcomes. As with other measures, recording of quality of life does not need to be complex and would seem to be of interest as an outcome in studies of this type.

1.6 Needs

No trial reported needs outcomes.

1.7 Social support

Perceived instrumental and emotional social support received from other people was higher for technology‐mediated patient education than for the standard care intervention. This result must be interpreted with great caution as it was based on one trial.

2. Comparison 2. Technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care intervention versus standard care intervention

We included five studies with a total of 725 participants.

2.1 Patient compliance

Five studies reported compliance with the intervention and one study compliance with medication. In the short term, the rate of participants leaving studies early was high (26%). In the long term it was low (10%). There was no difference between groups in the short or long term suggesting a similar overall acceptability of interventions. On the other hand, the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standardised care intervention may improve compliance with medication more than the standard care. This result, however, is based on limited data from one small Chinese study (n = 77, Chen 2007) and the result must be interpreted with caution.

2.2 Mental state

Altogether three studies recorded outcome for mental state. There was no significant difference in mental state between interventions as measured in one study as a binary outcome in the short term. Two studies used the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scale. The results of these studies were not consistent. Very limited data from the Chen 2007 study suggest that the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care intervention might be slightly more effective than the standard care intervention for mental state in the short, medium and long term. On the other hand, no difference between interventions was found in general, negative or positive symptoms in a large study (n = 363) (Hansson 2008). Although findings tended to fall on the side of the line favouring the technology‐medicated approach, there were no convincing data that a real and important effect of the experimental intervention exists. The converse is that no data exist to refute effectiveness or to suggest that further investigation is not indicated.

2.3 Global state

Again we found inconsistent results. One study found no difference between groups on the measure of global state (Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)); the other found in favour of the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care using the Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS). Both trials are small and this is also a finding that should be replicated.

2.4 Knowledge and insight

Knowledge and insight were measured as two binary outcomes in one study. We found no difference between interventions for insight. However, the technology‐mediated psychoeducation plus standard care intervention had more effect on knowledge than the standard care. This should not be taken as concrete evidence of a real effect and, as with other findings, should be replicated.

2.5 Quality of life ‐ long‐term