Abstract

Changes in developmental timing are an important factor of evolution in organ shape and function. This is particularly striking for human brain development, which, compared with other mammals, is considerably prolonged at the level of the cerebral cortex, resulting in brain neoteny. Here, we review recent findings that indicate that mitochondria and metabolism contribute to species differences in the tempo of cortical neuron development. Mitochondria display species-specific developmental timeline and metabolic activity patterns that are highly correlated with the speed of neuron maturation. Enhancing mitochondrial activity in human cortical neurons results in their accelerated maturation, while its reduction leads to decreased maturation rates in mouse neurons. Together with other global and gene-specific mechanisms, mitochondria thus act as a cellular hourglass of neuronal developmental tempo and may thereby contribute to species-specific features of human brain ontogeny.

Highlights

-

•

The human cerebral cortex is characterized by a protracted post-natal development (neoteny) compared with other species.

-

•

The species-specific rate of cortical neuron development relies largely on cell-intrinsic mechanisms.

-

•

Species-specific patterns of mitochondria development and metabolism are linked to the tempo of neuronal development.

-

•

Downstream and parallel mechanisms involve protein turnover, post-translation modifications, chromatin remodeling and human-specific genes.

Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2024, 86:102182

This review comes from a themed issue on Developmental mechanisms, patterning and evolution (2024): Developmental Timing

Edited by James Briscoe and Miki Ebisuya

For complete overview of the section, please refer to the article collection, “Developmental mechanisms, patterning and evolution (2024): Developmental Timing”

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2024.102182

0959–437X/© 2024 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Species-specific developmental timing and human brain evolution

Developmental timing is of particular importance for the human brain. In particular, the human cerebral cortex is characterized by a considerably protracted or neotenic development so that it retains markedly juvenile features until late adolescence. Human brain neoteny leads to extended critical periods of learning and neural plasticity, which have been proposed to play a key role in the acquisition of human-specific cognitive features [1]. At the cellular level, neurons of the human cerebral cortex are characterized by a prolonged timing of maturation compared with other species (reviewed in Ref. [2]). Cortical neurons complete their molecular, cellular, and functional development in a couple of weeks to months in the mouse, rat, and macaque brain, while in the human brain, it takes 1–3 years for cortical neurons to reach maturity in sensory cortical areas and up to two decades for those of the prefrontal cortex, the site of highest cognitive functions 2, 3, 4, 5. Importantly, most other types of neurons do not display such a prolonged developmental timing: for instance, the development of human spinal cord motor neurons takes about 2 weeks, and about 1 week for mouse counterparts [6]. Human brain neoteny is thus largely a cortical feature, leading to heterochronic development of different brain regions and cortical areas.

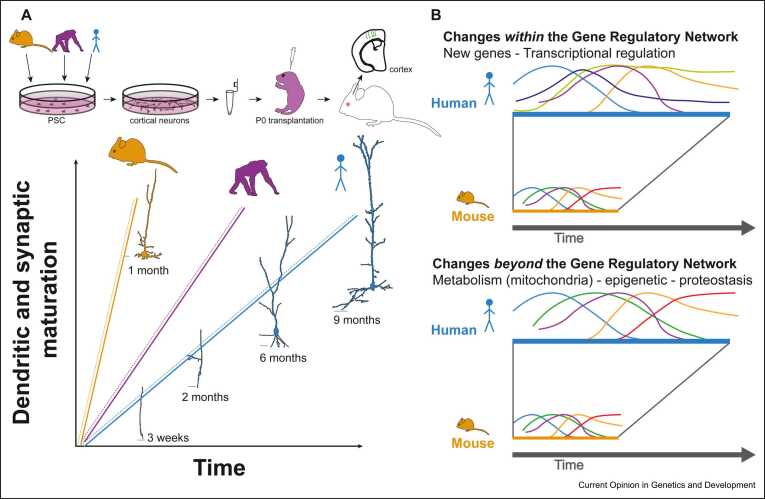

Remarkably, this timing difference between species is conserved in vitro for cortical neurons derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSC) of several species and cultured in the same conditions 7, 8, 9. Moreover, human and nonhuman primate cortical neurons derived from PSC and xenotransplanted into the mouse cortex still develop along their species-specific timelines 7, 10, 11 (Figure 1a). These data point to cell-intrinsic regulatory mechanisms regulating at least in part species-specific timing of neuronal development. But the molecular mechanisms that slow down developmental progression in human cortical neurons have remained largely unknown.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms underlying species-specific developmental timing of cortical neurons. (a) PSC-derived cortical neurons from different species xenotransplanted into mouse neonatal cortex develop at their own species-specific rate, pointing to cell-intrinsic regulatory mechanisms of developmental timing. Plain line: neurons in their native brain environment; dashed line: neurons xenotransplanted in the mouse. (b) Schematic representation of mechanisms of species-specific developmental timing. (upper panel) GRN components controlling neuronal development are divergent, thus containing species-specific patterns of gene expression or species-specific genes. (lower panel) The GRN is largely conserved between species, but the speed at which they progress over time is driven by divergent global processes, including mitochondria metabolism, chromatin remodeling, and proteostasis. Note that the two mechanisms are nonmutually exclusive: both participate to human cortical neuron neoteny. See text for more details.

Mechanisms underlying developmental timing: divergence ‘within’ and ‘beyond’ gene regulatory networks

Regulatory mechanisms of gene expression are the main target of evolution. The neotenic maturation of human cortical neurons is thus likely caused by the divergence in the gene regulatory networks (GRNs) underlying neuronal development (Figure 1b). Comparative studies of transcriptome and proteome have revealed not only a strong conservation of human and non-human cortical neuron developmental programs 12, 13 but also interesting differences. These include human-specific gene expression patterns at the RNA level, such as for the GATA3 transcription factor [14], or at protein levels, such as synaptic RhoGEFs [5]. Human-specific genes, that is, genes present only in the human genome and not in other species, have also been implicated in the tempo of cortical neuron development [15]. In particular, SRGAP2C, a human-specific paralog of the synaptic gene SRGAP2A, was shown to be necessary and sufficient for delayed dendritic spine maturation and synaptogenesis in human cortical neurons 16, 17.

However, overall, the divergent needles in the haystack of GRNs of human versus non-human cortical neurons have remained so far largely elusive.

A nonmutually exclusive possibility is that divergence in processes that do not participate directly to the GRN could influence the way it proceeds over time (Figure 1b). These could include global cellular mechanisms, such as RNA and protein turnover, intermediary metabolism, and chromatin landscape remodeling. Recent data focused on cortical development and on other systems in which the GRN appear to be much more conserved evolutionarily converge to the conclusion that some of these global mechanisms could indeed be linked to species-specific developmental tempo 6, 18, 19••, 20••, 21••. Here, we will focus on the potential links between intermediary metabolism — that is, the biochemical reactions that provide cells with energy, redox balance, and substrates for biosynthetic pathways — and species-specific developmental timing. Specifically, we will review the findings that point to mitochondria metabolism as a conductor of species-specific neuronal developmental tempo [21] and discuss their relevance to other timing mechanisms and systems.

Metabolism and mitochondria across species and in development

Species differences in intermediary metabolism have been long studied in the broader perspective of regulation of body size and lifespan, and the rate of embryonic development has been often found to be correlated to lifespan [22]. Indeed, metabolic rates are inversely correlated with body mass: specifically, the mass-specific resting metabolic rate, that is, the energy expense per gram of tissue and per unit of time, tends to be higher in small-bodied animals than in larger ones, a relationship commonly known as Kleiber’s law [22]. Some of these correlations were found to be conserved at the cellular level, in particular, in relation with mitochondrial oxidative metabolism [23], although it has remained unclear whether this is linked to cell or mitochondria differences across species.

On the other hand, mitochondria have been implicated in a variety of systems as a source of metabolic cues that regulate cell fate transition and acquisition 24, 25, 26. Enhancing mitochondria metabolism has also been shown to promote the maturation of non-neuronal cells 27, 28, 29, and mitochondria are required for neuronal and synaptic development and plasticity 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. These data suggest that mitochondria could be involved in neuronal developmental tempo, but this had never been tested until recently.

Species-specific mitochondria dynamics is correlated with neuronal developmental timing

Using a novel neuronal birth-dating system (NeuroD1-dependent Newborn Neuron [NNN] labeling; Figure 2a) coupled with mitochondria genetic tagging, mitochondrial growth and dynamics were first investigated in mouse and human developing cortical neurons in vitro and in vivo [21]. This revealed that, in newly born neurons, mitochondria are initially small in size and relatively sparse, consistent with previous reports [35]. Then, mitochondria gradually grow in size, number, and volume during the course of neuronal maturation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed these macrostructural changes in mouse and human cortical neurons in vivo. TEM also revealed parallel ultrastructural development, with mitochondria first displaying few cristae in newborn neurons, then displaying more and better defined cristae over time, suggestive of functional maturation [36].

Figure 2.

Linking mitochondria metabolism and the tempo of cortical neuron maturation. (a) Schematic of the NNN genetic labeling, which enables molecular and cellular analyses of neurons born at the same time. (b) Schematic of the relationships between mitochondria metabolism and neuronal developmental tempo across mouse and human species and following treatments leading to increased or decreased metabolism. Mouse cortical neurons display faster mitochondria development and higher metabolic rates than human counterparts. Increasing oxidative metabolism (oxphos) leads to increased mouse and human neuron maturation, while decreasing oxphos slows down mouse neuron maturation. Gray dashed line: experimental time of metabolomics analysis performed in mouse and human neurons at the same age. (c) Schematic of the metabolic patterns of mouse and human cortical neurons as measured at time point t represented in panel (b): higher aerobic glycolysis in human neurons and a higher mitochondrial metabolic activity in mouse neurons. (d) Schematic of the manipulation of metabolism of mouse or human cortical neurons and their impact on neuronal development. LDHA inhibition leads to increased pyruvate to lactate conversion, and AlbuMAX enrichment in fatty acid leads to increased acetyl-coA. Both treatments lead to increased mitochondrial metabolic activity, resulting in accelerated neuronal maturation rate. Inhibition of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier or of the complex I of the ETC results in decreased mitochondrial activity, which slows down mouse cortical neuron maturation.

Most strikingly, the timeline of mitochondrial changes displays major differences between the two species, with an increase in mitochondrial size and quantity spanning 2–3 weeks in mouse cortical neurons but several months in human cortical neurons.

Mitochondrial metabolic activity was then examined by measuring the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and the activity of the electron transport chain (ETC) of enriched preparations of genetically timed mouse and human cortical neurons [21]. This revealed a striking increase in oxidative activity of most ETC complexes during neuronal development, occurring much faster in mouse than in human neurons, in accordance with mitochondria morphological development. Notably, newly born mouse neurons displayed an increased mitochondria activity compared with human counterparts, in particular for the complex IV of the ETC, the last complex driving the electron flux converging from previous complexes toward ATP synthase.

To determine the mechanisms underlying these differences, 13C glucose–targeted metabolomics labeling experiments were performed on mouse and human cortical neurons of similar age. This revealed again species differences: compared with mouse neurons, human cortical neurons display higher levels of lactate production but lower levels of citrate, α-ketoglutarate, malate, aspartate, corresponding to metabolites engaged in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA; Figure 2c). This pattern, often referred to as aerobic glycolysis, reflects lower levels of mitochondria-dependent glucose metabolism. Interestingly, similar patterns were previously reported in vivo by human brain imaging, with strong aerobic glycolysis activity in the human developing cortex lasting for several years postnatally, particularly in the prefrontal cortex 37, 38.

Causal relationship between mitochondria metabolism and neuron developmental tempo

These findings overall indicate a strong correlation between mitochondria metabolic activity and neuronal developmental timing across mouse and human species. But are the metabolic differences causally linked to the tempo of neuronal maturation?

Based on species differences observed in the metabolomics experiments, two strategies were used to address this question [21]. First, mitochondrial activity was enhanced by increasing the entry of pyruvate into the TCA cycle. The pyruvate to lactate conversion is catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a tetrameric enzyme with isoenzymes composed of different proportions of two common subunits, A and B. LDHA favors the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, while LDHB favors the conversion of lactate to pyruvate [39]. Therefore, targeting the activity of LDHA with a chemical inhibitor (GSK-2837808A, referred to as GSK) was used to reduce pyruvate to lactate conversion and thereby to enhance mitochondria TCA cycle activity. Second, mitochondrial activity was further enhanced through another pathway by enriching the neuronal culture medium in free fatty acids (referred to as AlbuMAX), which following oxidation can feed further the TCA even in conditions of aerobic glycolysis.

The treatments were applied to human cortical neurons in vitro, alone or in combination, which led to a two- to three-fold increase in mitochondria oxidative activity in human neurons. The treatments were then applied for longer periods to human cortical neurons, followed by analyses of neuronal maturation. All treatments leading to enhanced mitochondria oxidative activity resulted in accelerated development of the human neurons, which reached maturation milestones weeks ahead of time, including increased growth and complexity of the dendritic arborization, together with an increased number of synapses. At the functional levels, the treated neurons displayed earlier acquisition of electrical excitability and synaptic function [21]. This could be confirmed in vivo using a xenotransplantation model of human cortical neurons in the mouse neonatal cortex [10]. Genetic enhancement of human neuron mitochondria metabolism was achieved by lentiviral overexpression of LDHB, resulting in an increase in dendritic length and complexity at 4 weeks post-transplantation, indicating an acceleration of human neuronal differentiation following mitochondria enhancement, also during in vivo differentiation [21].

Is the relationship between mitochondrial activity and neuronal maturation rate a fundamental mechanism conserved across species? Applying the same strategies on mouse cortical neurons resulted in increased dendritic length and complexity. Conversely, reduction of mitochondria activity, using inhibitors of pyruvate mitochondrial transport or ETC complex I, resulted in decreased rates of growth of dendrites, consistent with slower rates of development [21]. Thus, mitochondria dynamics and metabolism can set the tempo of neuronal development, providing a causal link between species-specific mitochondria metabolism and developmental timing in cortical neurons.

Mitochondria metabolism as a developmental timer in other cellular contexts

Is the control of developmental timing by mitochondria metabolism specific to neurons, or could it constitute a more general mechanism relevant to other developmental contexts? Another recent report identified mitochondria metabolism as a regulator of species-specific developmental timing in a completely different system: the somitic segmentation clock found in presomitic mesoderm (PSM) cells [20]. In this in vitro PSC-based model, PSM cells display gene expression oscillations, the so-called segmentation clock, that mimic those found during normal development of the somites. Most importantly, these oscillations are based upon a highly conserved GRN, but they display temporal species-specificity, with mouse PSM cells oscillating twice as fast as human counterparts (period of oscillation of 2 hours versus 5 hours, respectively) 18, 19••, 20••. Both mitochondria biomass and oxidative activity per cell mass were found to be twofold higher in mouse than in human cells, in scale with the segmentation clock speed differences [20]. Metabolic analyses and functional experiments identified Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+)/Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide - reduced (NADH) balance as a causative factor of the developmental clock speed. Thus, metabolic rates can be linked to developmental tempo in two very different developmental contexts: PSM cells are mitotic and display hours-long oscillatory gene expression pattern, while neurons are postmitotic and undergo irreversible differentiation over weeks to months of time. On the other hand, another study comparing PSM cells from six mammalian species failed to detect correlations between mitochondria oxidative activity and somitic clock developmental timing [19]. Thus, mitochondria oxidative metabolism alone may not explain the differential tempo of PSM cells, which likely involve additional metabolic or nonmetabolic processes. Their identification will require deeper analyses across species and systems with metabolomic and proteomic approaches to determine whether mitochondria metabolism contributes to developmental timing as part of a ‘universal hourglass’ or as one of several cell-specific and context-dependent timers. In this context, it will be fascinating to explore whether and how metabolism impacts other neural cell types that develop along cell-specific and species-specific temporal scales. For instance, some glial cells, most strikingly oligodendrocytes, also develop in a much protracted fashion in the human brain [2], while development of human spinal cord motor neurons is much faster than cortical neurons [6].

On the other hand, while current data indicate a strong cell-intrinsic link between metabolism and developmental timing, it remains to be tested whether extrinsic mechanisms, such as blood vessel development and remodeling or availability of metabolic substrates, also play a role in brain neoteny.

Downstream and parallel mechanisms: protein turnover, post-translation modifications, chromatin remodeling

Another key unanswered question is the nature of the downstream mechanisms by which mitochondria metabolism influences developmental timing. Metabolic rates could alter the species-specific turnover rate of RNAs and proteins, which are highly dependent on ATP and mitochondria activity 40, 41•. Moreover, using the PSM model as well as spinal cord motor neuron development, species differences in the global rates of RNA/protein turnover were detected, from mRNA splicing export and degradation to protein synthesis and degradation, which could be correlated with the scale of species differences in developmental timing 6, 18, 19••. These data suggest that metabolic activity could drive developmental tempo by influencing RNA/protein turnover rates. Consistent with this hypothesis, the higher levels of NAD+/NADH found in mouse PSM compared with human counterparts could be linked causally to higher rates of protein translation [20]. In addition, the rates of protein translation, but not those of protein degradation by the proteasome, were found to influence the somitic clock pace [20]. Mitochondria have also been shown to fuel local protein synthesis required for synaptic plasticity [30], but whether protein synthesis regulation could also influence neuronal maturation tempo remains to be tested.

Another way by which intermediary metabolism could influence developmental tempo is through post-translational modifications (PTM) that are modulated by metabolites [42]. Variations in levels of nutrient uptake, glycolytic and lipolytic fluxes, TCA, and oxidative phosphorylation activities can all result in different concentrations of metabolites as well as physicochemical parameters, such as pH, redox balance, and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Many of these metabolites then serve as substrates or regulators of PTM, including methylation/demethylation, acetylation/deacetylation, o-glycosylation, as well as DNA methylation 42, 43. Histones are important targets of such PTMs, which in turn can affect gene expression by epigenetic regulation of chromatin state. Histone PTM remodeling was recently linked causally to neuronal development in mouse cerebellar and human cortical neurons, pointing to methylation dynamics in both cases 44, 45. In particular, recent work has identified a key role of histone methylation to modulate the speed of maturation of human cortical neurons in vitro [46]. While it remains to be tested to which extent histone remodeling dynamics in orthologous neurons displays differences across species, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that species-specific mitochondria metabolism could control developmental timing at least in part by influencing chromatin remodeling turnover.

Finally, the impact of mitochondria on metabolism per se should not be underestimated, as the dynamics of anabolism and catabolism of biomolecules could directly influence developmental timing. For instance, beyond ATP production, mitochondria respiration is required to provide electron acceptors to support de novo aspartate biosynthesis, which itself is a key anabolic substrate for purine and pyrimidine as well as protein synthesis, both of which are key in any process of cell growth or division [47].

Mechanisms underlying species-specific mitochondria metabolism

Another key unanswered question concerns the mechanisms upstream of the species-specific metabolic profiles observed in neuronal or other systems. In this respect, it is interesting to note that while mitochondria enhancing treatments described above could enhance mitochondrial activity, the OCR in treated human neurons was still much lower than in mouse neurons of similar age [21]. This indicates that additional mechanisms contribute to increased mitochondrial activity in mouse neurons. The observed species differences in mitochondria function may originate from patterns of mitochondria gene regulatory mechanisms [21] or human-specific mitochondrial proteins [48] but likely also involve post-translational mechanisms such as modifications of mitochondrial dynamics and assembly of the ETC [49]. The developmental patterns and species differences displayed by mitochondria resonate with the emerging evidence that they display a high level of proteomic heterogeneity across diverse cell types [50].

It will be fascinating to decipher what are the mechanisms that regulate the levels of mitochondria metabolism in relation with cellular or developmental context and how these relate to the observed species-specific patterns.

Implications for brain diseases and evolution

The finding that mitochondria metabolism regulates neuronal developmental tempo could have interesting implications for neurodevelopmental diseases, in particular, intellectual deficiency (ID) and autism spectrum disorders (ASD). The pathogenic mechanisms of classical ID/ASD forms are thought to be mostly related to synaptic development and function, but mitochondria metabolism could be involved as well, as recently shown for human neurons displaying pathogenic mutations of Fragile X and Rett syndromes 31, 51. Conversely, defects in developmental timing could be part of the mechanisms underlying the many neuronal defects found following pathogenic mutations in mitochondria disease genes 34, 52. It will also be important to explore whether and how mitochondria metabolism interacts with other pathways involved in human neuron neoteny, such as the human-specific genes of the SRGAP2 family 16, 17.

More generally, the identification of metabolic pathways that regulate neuronal developmental tempo offers new opportunities to test whether and how neuronal neoteny of human cortical neurons impacts the function and plasticity of cortical circuits in healthy and pathological contexts.

Conclusion and perspectives

In conclusion, the recent findings reviewed here point to global processes, in particular, intermediary metabolism, as key regulators of the scale of neuronal developmental timing across species. Exciting future work should enable to determine the relationships between the various mechanisms recently identified and their respective involvement to timing in different developmental contexts. The resolution of these important questions will require deeper molecular analyses of global metabolic processes across developmental time and species, including in vivo, thanks to deep metabolomic approaches in vitro but also in vivo 53, 54, 55•. This will provide key mechanistic insights and useful hints to design novel ways to address causality between metabolic and developmental processes with the required sensitivity and specificity. On the other hand, the surprising contribution of mitochondria metabolism to human cortical neoteny should be explored further, as it is likely to bring novel insights on human brain evolution and diseases.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank PV lab members for helpful discussions. The work from PV lab described here was funded by the European Research Council, EU (NEUROTEMPO), the C1 KU Leuven Programme, Belgium, the EOS Programme PANDAROME, Belgium, the Belgian FWO, the Generet Fund, Belgium (to PV), the Belgian Queen Elisabeth Foundation (to RI and PV). RI was supported by a postdoctoral Fellowship of the FRS/FNRS, and PC was supported by a PhD Fellowship of the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, Flanders, Belgium (FWO file number 51989).

Data Availability

No data were used for the research described in the article.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

-

•

of special interest

-

••

of outstanding interest

- 1.Sherwood C.C., Gomez-Robles A. Brain plasticity and human evolution. Annu Rev Anthr. 2017;46:399–419. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanderhaeghen P., Polleux F. Developmental mechanisms underlying the evolution of human cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2023;24:213–232. doi: 10.1038/s41583-023-00675-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Y., Sousa A.M.M., Gao T., Skarica M., Li M., Santpere G., Esteller-Cucala P., Juan D., Ferrández-Peral L., Gulden F.O., et al. Spatiotemporal transcriptomic divergence across human and macaque brain development. Science. 2018;362 doi: 10.1126/science.aat8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wildenberg G., Li H., Sampathkumar V., Sorokina A., Kasthuri N. Isochronic development of cortical synapses in primates and mice. Nat Commun. 2023;14 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Pang K., Zhou L., Cebrián-Silla A., González-Granero S., Wang S., Bi Q., White M.L., Ho B., Li J., et al. A cross-species proteomic map reveals neoteny of human synapse development. Nature. 2023;622:112–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06542-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rayon T., Stamataki D., Perez-Carrasco R., Garcia-Perez L., Barrington C., Melchionda M., Exelby K., Lazaro J., Tybulewicz V.L.J., Fisher E.M.C., et al. Species-specific pace of development is associated with differences in protein stability. Science. 2020;369:1449. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7667. eaba7667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espuny-camacho I., Michelsen K., Gall D., Linaro D., Hasche A., Bonnefont J., Bali C., Orduz D., Bilheu A., Herpoel A., et al. Pyramidal neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells integrate efficiently into mouse brain circuits in vivo. Neuron. 2013;77:440–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otani T., Marchetto M.C., Gage F.H., Simons B.D., Livesey F.J. 2D and 3D stem cell models of primate cortical development identify species-specific differences in progenitor behavior contributing to brain size. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schörnig M., Ju X., Fast L., Ebert S., Weigert A., Kanton S., Schaffer T., Kasri N.N., Treutlein B., Peter B., et al. Comparison of induced neurons reveals slower structural and functional maturation in humans than in apes. Elife. 2021;10:1–78. doi: 10.7554/eLife.59323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linaro D., Vermaercke B., Iwata R., Ramaswamy A., Libé-Philippot B., Boubakar L., Davis B.A.B.A., Wierda K., Davie K., Poovathingal S., et al. Xenotransplanted human cortical neurons reveal species-specific development and functional integration into mouse visual circuits. Neuron. 2019;104:972–986.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchetto M.C., Hrvoj-Mihic B., Kerman B.E., Yu D.X., Vadodaria K.C., Linker S.B., Narvaiza I., Santos R., Denli A.M., Mendes A.P.D., et al. Species-specific maturation profiles of human, chimpanzee and bonobo neural cells. Elife. 2019;8:1–23. doi: 10.7554/eLife.37527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollen A.A., Nowakowski T.J., Chen J., Retallack H., Sandoval-Espinosa C., Nicholas C.R., Shuga J., Liu S.J., Oldham M.C., Diaz A., et al. Molecular identity of human outer radial glia during cortical development. Cell. 2015;163:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sousa A.M.M., Zhu Y., Raghanti M.A., Kitchen R.R., Onorati M., Tebbenkamp A.T.N., Stutz B., Meyer K.A., Li M., Kawasawa Y.I., et al. Molecular and cellular reorganization of neural circuits in the human lineage. Science. 2017;358:1027–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linker S.B., Narvaiza I., Hsu J.Y., Wang M., Qiu F., Mendes A.P.D., Oefner R., Kottilil K., Sharma A., Randolph-Moore L., et al. Human-specific regulation of neural maturation identified by cross-primate transcriptomics. Curr Biol. 2022;32:4797–4807.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki I.K., Gacquer D., Van Heurck R., Kumar D., Wojno M., Bilheu A., Herpoel A., Lambert N., Cheron J., Polleux F., et al. Human-specific NOTCH2NL genes expand cortical neurogenesis through delta/notch regulation. Cell. 2018;173:1370–1384.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baptiste Libé-Philippot, Ryohei Iwata, Alesksandra J Recupero, Keimpe Wierda, Martyna Ditkowska, VaivaGaspariunaite, Ben Vermaercke, Eugénie Peze-Heidsieck, Daan Remans, CécileCharrier, Franck Polleux, Pierre Vanderhaeghen: Human synaptic neoteny requiresspecies-specific balancing of SRGAP2-SYNGAP1 cross-inhibition, bioRxiv2023.03.01.530630; doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1101/2023.03.01.530630. [DOI]

- 17.Charrier C., Joshi K., Coutinho-Budd J., Kim J.E., Lambert N., de Marchena J., Jin W.L., Vanderhaeghen P., Ghosh A., Sassa T., et al. Inhibition of SRGAP2 function by its human-specific paralogs induces neoteny during spine maturation. Cell. 2012;149:923–935. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda M., Hayashi H., Garcia-Ojalvo J., Yoshioka-Kobayashi K., Kageyama R., Yamanaka Y., Ikeya M., Toguchida J., Alev C., Ebisuya M. Species-specific segmentation clock periods are due to differential biochemical reaction speeds. Science. 2020;1455:1450–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Lázaro J., Costanzo M., Sanaki-Matsumiya M., Girardot C., Hayashi M., Hayashi K., Diecke S., Hildebrandt T.B., Lazzari G., Wu J., et al. A stem cell zoo uncovers intracellular scaling of developmental tempo across mammals. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30:938–949.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using the somitic segmentation model, Lázaro et al. document the segmentation clock period in six mammalian species and find a correlation with protein turnover but none with mitochondrial oxidative activity.

- 20••.Diaz-Cuadros M., Miettinen T.P., Skinner O.S., Sheedy D., Díaz-García C.M., Gapon S., Hubaud A., Yellen G., Manalis S.R., Oldham W.M., et al. Metabolic regulation of species-specific developmental rates. Nature. 2023;613:550–557. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05574-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Diaz-Cuadros et al. link mass-specific metabolic oxidative activity and developmental rate using the somitic segmentation model. They identify the NAD/NADH redox balance as a key biochemical parameter affecting downstream biochemical reactions, including protein translation.

- 21••.Iwata R., Casimir P., Erkol E., Boubakar L., Planque M., Gallego I.M., Ditkowska M., Gaspariunaite V., Beckers S., Remans D., et al. Mitochondria metabolism sets the species-specific tempo of neuronal development. Science. 2023;379 doi: 10.1126/science.abn4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Iwata et al. uncover species-specific patterns of mitochondrial dynamics and activity during cortical neuron maturation and demonstrate a causal relationship between mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and cortical neuron maturation rate.

- 22.West G.B., Brown J.H., Enquist B.J. A general model for ontogenetic growth. Nature. 2001;413:628–631. doi: 10.1038/35098076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter R.K. Allometry of mammalian cellular oxygen consumption. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:815–822. doi: 10.1007/PL00000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwata R., Vanderhaeghen P. Regulatory roles of mitochondria and metabolism in neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021;69:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakrabarty R.P., Chandel N.S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles control mammalian stem cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:394–408. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H., Menzies K.J., Auwerx J. The role of mitochondria in stem cell fate and aging. Development. 2018;145 doi: 10.1242/dev.143420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X., Rodriguez M.L., Leonard A., Sun L., Fischer K.A., Wang Y., Ritterhoff J., Zhao L., Kolwicz S.C., Pabon L., et al. Fatty acids enhance the maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2019;13:657–668. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu D., Linders A., Yamak A., Correia C., Kijlstra J.D., Garakani A., Xiao L., Milan D.J., Van Der Meer P., Serra M., et al. Metabolic maturation of human pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes by inhibition of HIF1α and LDHA. Circ Res. 2018;123:1066–1079. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshihara E., Wei Z., Lin C.S., Fang S., Ahmadian M., Kida Y., Tseng T., Dai Y., Yu R.T., Liddle C., et al. ERRγ is required for the metabolic maturation of therapeutically functional glucose-responsive β cells. Cell Metab. 2016;23:622–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rangaraju V., Lauterbach M., Schuman E.M. Spatially stable mitochondrial compartments fuel local translation during plasticity. Cell. 2019;176:73–84.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Licznerski P., Park H., Rolyan H., Gribkoff V.K., Levy R.J., Jonas E.A., Licznerski P., Park H., Rolyan H., Chen R., et al. ATP synthase c-subunit leak causes aberrant cellular metabolism in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 2020;182:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatsuda A., Kurisu J., Fujishima K., Kawaguchi A., Ohno N., Kengaku M. Calcium signals tune AMPK activity and mitochondrial homeostasis in dendrites of developing neurons. Development. 2023;150 doi: 10.1242/dev.201930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorenz C., Prigione A. Mitochondrial metabolism in early neural fate and its relevance for neuronal disease modeling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;49:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inak G., Rybak-wolf A., Lisowski P., Pentimalli T.M., Jüttner R., Gla P., Uppal K., Bottani E., Brunetti D., Secker C., et al. Defective metabolic programming impairs early neuronal morphogenesis in neural cultures and an organoid model of Leigh syndrome. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–22. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22117-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwata R., Casimir P., Vanderhaeghen P. Mitochondrial dynamics in postmitotic cells regulate neurogenesis. Science. 2020;862:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker N., Patel J., Khacho M. Linking mitochondrial dynamics, cristae remodeling and supercomplex formation: how mitochondrial structure can regulate bioenergetics. Mitochondrion. 2019;49:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goyal M.S., Hawrylycz M., Miller J.A., Snyder A.Z., Raichle M.E. Aerobic glycolysis in the human brain is associated with development and neotenous gene expression. Cell Metab. 2014;19:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaishnavi S.N., Vlassenko A.G., Rundle M.M., Snyder A.Z., Mintun M.A., Raichle M.E. Regional aerobic glycolysis in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17757–17762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valvona C.J., Fillmore H.L., Nunn P.B., Pilkington G.J. The regulation and function of lactate dehydrogenase A: therapeutic potential in brain tumor. Brain Pathol. 2016;26:3–17. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sala A.J., Bott L.C., Morimoto R.I. Shaping proteostasis at the cellular, tissue, and organismal level. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:1231–1241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Swovick K., Firsanov D., Welle K.A., Hryhorenko J.R., Wise J.P., George C., Sformo T.L., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V., Ghaemmaghami S. Interspecies differences in proteome turnover kinetics are correlated with life spans and energetic demands. Mol Cell Proteom. 2021;20 doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA120.002301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Swovick et al. document that protein turnover of abundant proteins is correlated with life span across species and that long-lived species tend to produce less ATP and ROS while displaying a higher resistance to protein misfolding stress.

- 42.Baker S.A., Rutter J. Metabolites as signalling molecules. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:355–374. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00572-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai Z., Ramesh V., Locasale J.W. The evolving metabolic landscape of chromatin biology and epigenetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21:737–753. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramesh V., Liu F., Minto M.S., Chan U., West A.E. Bidirectional regulation of postmitotic H3K27me3 distributions underlie cerebellar granule neuron maturation dynamics. Elife. 2023;12:86273. doi: 10.7554/eLife.86273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mätlik K., Govek E.E., Paul M.R., Allis C.D., Hatten M.E. Histone bivalency regulates the timing of cerebellar granule cell development. Genes Dev. 2023;37:570–589. doi: 10.1101/gad.350594.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46••.Ciceri G., Baggiolini A., Cho H.S., Kshirsagar M., Benito-Kwiecinski S., Walsh R.M., Aromolaran K.A., Gonzalez-Hernandez A.J., Munguba H., Koo S.Y., et al. An epigenetic barrier sets the timing of human neuronal maturation. Nature. 2024 doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06984-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Refs. [44–46] implicate Histone methylation dynamics in the regulation of neuronal developmental timing. (46) identified an epigenetic barrier at the levels of neural progenitors that delays human cortical neuron development.

- 47.Sullivan L.B., Gui D.Y., Hosios A.M., Bush L.N., Freinkman E., Vander Heiden M.G. Supporting aspartate biosynthesis is an essential function of respiration in proliferating cells. Cell. 2015;162:552–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Namba T., Dóczi J., Pinson A., Xing L., Kalebic N., Wilsch-Bräuninger M., Long K.R., Vaid S., Lauer J., Bogdanova A., et al. Human-specific ARHGAP11B acts in mitochondria to expand neocortical progenitors by glutaminolysis. Neuron. 2020;105:867–881.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giacomello M., Pyakurel A., Glytsou C., Scorrano L. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:204–224. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fecher C., Trovò L., Müller S.A., Snaidero N., Wettmarshausen J., Heink S., Ortiz O., Wagner I., Kühn R., Hartmann J., et al. Cell-type-specific profiling of brain mitochondria reveals functional and molecular diversity. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1731–1742. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0479-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zlatic S.A., Werner E., Surapaneni V., Lee C.E., Gokhale A., Singleton K., Duong D., Crocker A., Gentile K., Middleton F., et al. Systemic proteome phenotypes reveal defective metabolic flexibility in Mecp2 mutants. Hum Mol Genet. 2023;33:12–32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddad154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romero-Morales A.I., Robertson G.L., Rastogi A., Rasmussen M.L., Temuri H., McElroy G.S., Chakrabarty R.P., Hsu L., Almonacid P.M., Millis B.A., et al. Human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids model features of Leigh syndrome and reveal abnormal corticogenesis. Development. 2022;149 doi: 10.1242/dev.199914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Planque M., Igelmann S., Margarida A., Fendt S.-M. Spatial metabolomics principles and application to cancer. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2023;76:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102362. (in press:) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solmonson A., Faubert B., Gu W., Rao A., Cowdin M.A., Menendez-Montes I., Kelekar S., Rogers T.J., Pan C., Guevara G., et al. Compartmentalized metabolism supports midgestation mammalian development. Nature. 2022;604:349–353. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55•.Perez-Ramirez C.A., Nakano H., Law R.C., Matulionis N., Thompson J., Pfeiffer A., Park J.O., Nakano A., Christofk H.R. Atlas of fetal metabolism during mid-to-late gestation and diabetic pregnancy. Cell. 2024;187:204–215.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Refs. [54,55] A striking illustration of how in vivo metabolomic approaches can uncover mechanistic links between metabolic flows and development.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.