This review of a scoping review analyzes the intensity and complexity of social needs interventions in randomized clinical trials and whether the trials were designed to assess the effect of individual intervention components on health outcomes.

Key Points

Question

What is the intensity and complexity of different social needs interventions, and what is the potential for causal inference about specific intervention components?

Findings

This review of a scoping review examined 77 randomized clinical trials of social needs interventions; the majority (68 studies [88%]) described features indicating high intervention intensity and all studies reported features indicating high intervention complexity. Study designs permitted conclusions on overall effectiveness but typically did not permit casual inferences about individual intervention components.

Meaning

These findings suggest that social needs–related interventions undertaken in health care settings are often complex and intensive and have generally not been designed to assess the causal effects of specific components.

Abstract

Importance

Interventions that address needs such as low income, housing instability, and safety are increasingly appearing in the health care sector as part of multifaceted efforts to improve health and health equity, but evidence relevant to scaling these social needs interventions is limited.

Objective

To summarize the intensity and complexity of social needs interventions included in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and assess whether these RCTs were designed to measure the causal effects of intervention components on behavioral, health, or health care utilization outcomes.

Evidence Review

This review of a scoping review was based on a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute–funded evidence map of English-language US-based RCTs of social needs interventions published between January 1, 1995, and April 6, 2023. Studies were assessed for features related to intensity (defined using modal values as providing as-needed interaction, 8 participant contacts or more, contacts occurring every 2 weeks or more often, encounters of 30 minutes or longer, contacts over 6 months or longer, or home visits), complexity (defined as addressing multiple social needs, having dedicated staff, involving multiple intervention components or practitioners, aiming to change multiple participant behaviors [knowledge, action, or practice], requiring or providing resources or active assistance with resources, and permitting tailoring), and the ability to assess causal inferences of components (assessing interventions, comparators, and context).

Findings

This review of a scoping review of social needs interventions identified 77 RCTs in 93 publications with a total of 135 690 participants. Most articles (68 RCTs [88%]) reported 1 or more features of high intensity. All studies reported 1 or more features indicative of high complexity. Because most studies compared usual care with multicomponent interventions that were moderately or highly dependent on context and individual factors, their designs permitted causal inferences about overall effectiveness but not about individual components.

Conclusions and Relevance

Social needs interventions are complex, intense, and include multiple components. Our findings suggest that RCTs of these interventions address overall intervention effectiveness but are rarely designed to distinguish the causal effects of specific components despite being resource intensive. Future studies with hybrid effectiveness-implementation and sequential designs, and more standardized reporting of intervention intensity and complexity could help stakeholders assess the return on investment of these interventions.

Introduction

Intervening to improve social determinants of health—“the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age”1—has increasingly been heralded as critical to improving health equity.2,3,4,5 Social determinants include both upstream structural and societal systems, policies, and norms and the downstream manifestations of those upstream factors, such as the day-to-day availability of food, transportation, housing, and safety. These downstream manifestations of social adversity are often referred to as social risks.6 More recently, the health care sector has begun to support health care activities focused on reducing social risks (ie, social care or social needs interventions).6 New state and federal policies are designed to incentivize the uptake of these interventions.7,8,9,10

The value of social needs interventions needs to be assessed to understand the extent of health care sector involvement. Although several studies have suggested that social needs interventions undertaken in health care settings may improve health outcomes11 without increasing (and sometimes even lowering) health care costs,12,13,14,15 the added value of individual intervention components has received relatively little attention. By design, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) assess the effect of interventions on measured outcomes, but major barriers to uptake of social needs interventions include the lack of resources to implement and sustain these programs.16,17 As a result, assessing value also requires detailed information about the feasibility of implementation to help allocate scarce resources such as staff time, technology, and partnerships. Information about these program costs can be garnered from intervention intensity (eg, duration and extent of patient contacts) and intervention complexity (eg, range of needs addressed, intervention components).

To begin to inform implementation and scalability questions, we undertook this review of a scoping review of RCTs to better understand what the current literature reveals about the intensity and complexity of existing intervention models and the contribution of components of social needs interventions to health and health care utilization outcomes. Although numerous prior systematic and scoping reviews have synthesized the evidence on social care and social needs interventions,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 to our knowledge, this review of a scoping review is the first to focus on these crucial precursors to implementation and scalability. Specifically, we focus on (1) intensity and complexity of social needs interventions and (2) measurement of the effects of individual components or combinations of intervention components on behavioral, health, or health care utilization outcomes.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

This review of a scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.26,27,28 Our data source was a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute–funded, web-based repository and visualization of social needs interventions in health care settings,29 which was built on systematic searches of articles in MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library published between January 1, 1995, and April 6, 2023; reference searches of relevant systematic reviews and companion articles; and consultation with subject matter experts (eTables 1-12 in Supplement 1). We registered the protocol for this review of a scoping review in the Open Science Framework.30

Study Selection

eTable 13, the eMethods, and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 detail the criteria used to select studies.29 The review selected English-language RCTs set in the US that addressed participant-level social needs31,32 and reported behavioral, health, or health care utilization outcomes or harms. A pair of investigators (M.V. and S.M.K., N.S. and M.L.E., or V.N. and S.K.) independently reviewed titles, abstracts, and full-text articles; disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer (M.V. or M.L.E.).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A reviewer (S.M.K., N.S., V.N., or S.K.) extracted population and intervention characteristics, social needs addressed (eResults in Supplement 1), recruitment and intervention setting, and intervention practitioner; a second reviewer (M.V., M.L.E., or N.S.) checked for accuracy. A reviewer (M.V., N.S., or M.L.E.) assessed the risk of bias using the Risk of Bias 2.0 instrument,33 and a second reviewer (M.V., N.S., or M.L.E.) spot-checked the studies (eTable 14 in Supplement 1).

To understand intensity of social needs interventions, we extracted information on the number, duration, and frequency of contacts and the time period over which the contacts occurred.34 Given the underlying heterogeneity, we did not define thresholds a priori; instead, we employed an exploratory approach. Specifically, we selected the modal value to categorize the distribution as suggestive of lower vs higher intensity ( <8 contacts vs ≥8 contacts, mode = 8; less often than every 2 weeks vs 2 weeks or more often, mode = 2 weeks; <30 minutes vs ≥30 minutes, mode = 30 minutes; <6 months vs ≥6 months, mode = 6 months). Studies that planned to vary intensity based on participant needs were included in the high-intensity category (ie, varied by need) because they were designed to accommodate high intensity for at least some participants.

To capture features of complexity, we used the Complexity Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (iCAT-SR).35 Overall, we applied 5 of the 10 dimensions of the iCAT-SR tool to disaggregate complex interventions (eTable 15 and eTable 16 in Supplement 1). For complexity specifically, we included number of components (iCAT-SR dimension 1), behavior changes targeted in recipients (knowledge, action, or practice) (iCAT-SR dimension 2), and degree of tailoring intended or permitted (iCAT-SR dimension 4).35 Additionally, we assessed whether interventions addressed multiple social needs, had dedicated staff, involved multiple practitioners, and provided resources and/or active assistance with resources or required resources to implement (eg, information, economic supports, food, transportation, supplies, referral for participants, staff, training, time, space, or monetary resources).

We also applied the iCAT-SR framework to assess whether each study’s design permitted attribution of effects to 1 or more intervention components. We used 3 specific iCAT-SR criteria, either in combination with study design features or independently. First, we evaluated whether the studies could isolate the effect of the social needs intervention component. Studies comparing usual care plus a single-component social needs intervention with usual care alone permit causal inference on the effects of the single component; factorial trial designs may similarly permit causal inference regarding individual components. Prespecified or post hoc analyses of intervention components may not necessarily support causal inference because they may conflate selection and treatment effects, but they can offer an upper bound on the likely treatment effect.36 Multicomponent interventions (iCAT-SR dimension 1) and interventions addressing a combination of medical and social needs that have no prespecified or post hoc analyses of the effectiveness of intervention components address overall effectiveness but not the effectiveness of individual social needs components. Second, we judged whether context or setting (iCAT-SR dimension 8) or individual-level recipient or practitioner factors (iCAT-SR dimension 9) were likely to modify the effect of the intervention. Interventions that could be delivered under various settings with minimal modification were assessed as independent of context. Interventions likely to yield different results by setting or fully intertwined within a complex setting were moderately or highly dependent on context. Studies moderately or highly dependent on context and individual factors without additional analyses were judged as being unable to parse the effects of the intervention from the effects of context and individual factors.

Data Analysis

We relied primarily on descriptive analyses. These analyses were supported by study counts and percentages (from proportions of all studies) and supplemented by qualitative syntheses of individual data elements.

Results

We reviewed 15 114 references from database searches, 917 references from the Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network, and 475 references from hand searches of systematic reviews, for a total of 16 506 references. We excluded 15 010 references at title and abstract review and assessed the full text of 1496 references. We excluded 1419 references at full-text review and included 77 RCTs36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112 reporting on 78 interventions in 93 publications with a total of 135 690 participants (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

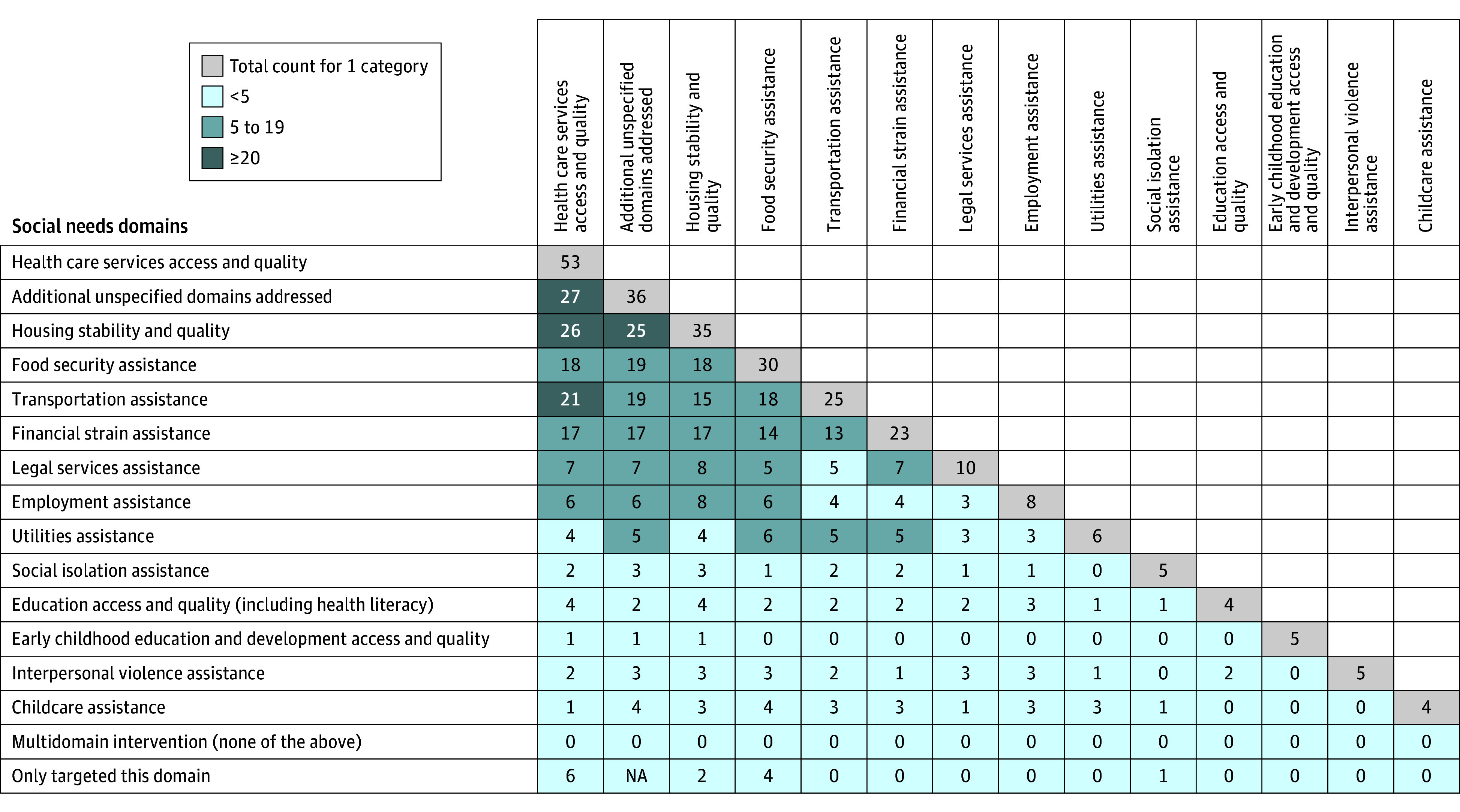

Table 1 and eTable 17 in Supplement 1 present study and population characteristics. Of the 77 RCTs, 34 (44%) addressed both social and medical needs38,40,41,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,56,57,58,59,60,65,66,69,70,73,74,75,76,77,82,84,90,92,94,97,101,104,108 and 43 (56%) involved no medical care intervention component36,37,39,42,43,44,45,53,55,61,62,63,64,67,68,71,72,78,79,80,81,83,85,86,87,88,89,91,93,95,96,98,99,100,102,103,105,106,107,109,110,111,112; yet, all interventions were affiliated with or in health care settings, so participants may have received medical care indirectly. Nearly one-third addressed just 1 prespecified social need (25 RCTs [32%])36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,61,63,64,68,73,90,93,95,96,102,105,107,109,110,111,112; the remainder (52 RCTs [68%]) addressed multiple social needs.40,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,65,66,67,69,70,71,72,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,91,92,94,97,98,99,100,101,103,104,106,108 The most frequently addressed social needs, alone or combined with other social needs, were health care access and quality (53 RCTs [69%]),36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,88,89,97,99,106,108,111 housing stability and quality (35 RCTs [45%]),40,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,59,62,65,69,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,85,86,87,88,90,91,92,93,94,95,103,106 food security (30 RCTs [39%]),48,50,53,56,58,59,61,62,63,64,65,70,72,74,76,77,78,81,82,85,86,87,91,92,96,98,101,103,104,109 transportation (25 RCTs [32%]),47,48,50,52,53,55,56,57,58,62,65,66,67,72,74,76,77,81,85,86,92,94,97,101,104 and financial strain (23 RCTs [30%])46,47,48,51,54,56,58,62,65,72,76,80,82,83,86,87,92,94,98,99,101,104,106 (Figure). Nearly one-half of the studies (36 RCTs [47%]) also addressed additional unspecified social domains.46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,60,62,65,67,71,72,74,75,77,78,79,83,85,86,87,89,91,92,94,100,103,104,106

Table 1. Study and Population Characteristics.

| Study characteristic | Randomized clinical trials, No. (%) (N =77) |

|---|---|

| Randomization | |

| Individually randomized parallel-group trial | 72 (94) |

| Cluster-randomized parallel-group trial | 5 (6) |

| Quality | |

| High | 17 (22) |

| Medium | 38 (49) |

| Low | 22 (29) |

| Comparator | |

| Usual care | 59 (77) |

| Active control | 9 (12) |

| Waitlist control | 4 (5) |

| Other inactive control | 3 (4) |

| Other | 2 (3) |

| Target domain type | |

| Social need program | 43 (56) |

| Medical and social need program | 34 (44) |

| No. of social need domains addresseda | |

| 1 specified need | 25 (32) |

| 1 specified need and additional unspecified needs | 4 (5) |

| 2 specified needs | 9 (12) |

| 2 specified needs and additional unspecified needs | 5 (6) |

| 3 specified needs | 3 (4) |

| 3 specified needs and additional unspecified needs | 5 (6) |

| 4 specified needs | 2 (3) |

| 4 specified needs and additional unspecified needs | 11 (14) |

| 5 specified needs | 0 |

| 5 specified needs and additional unspecified needs | 8 (10) |

| ≥ 6 specified needs | 2 (3) |

| ≥ 6 specified needs and additional unspecified needs | 3 (4) |

| Age groupb | |

| Children (<18 y) or children and their families | 15 (19) |

| Adolescents and young adults (13-20 y) | 9 (12) |

| Adults (≥18 y) | 56 (73) |

| Older adults ( ≥50 y) | 52 (68) |

| Only older adults (≥50 y) | 6 (8) |

| Majority race or ethnicityc | |

| Majority Asian or Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Majority Black or Non-Hispanic Black | 24 (36) |

| Majority Hispanic or Latino | 12 (18) |

| Majority Native American, American Indian, or Indigenous | 0 |

| Majority White or Non-Hispanic White | 16 (24) |

| No single group is a majority | 15 (22) |

| Not reported | 10 (NA) |

| Sex (proportion female) | |

| <50% | 31 (42) |

| ≥50% | 42 (58) |

| Not reported | 4 (NA) |

| Required clinical condition | |

| Mental health | 11 (29) |

| Chronic condition(s)d | 9 (24) |

| Diabetes | 5 (13) |

| Asthma | 3 (8) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 (8) |

| Preterm birth | 2 (5) |

| Blind or disabled | 1 (3) |

| Heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (3) |

| Obesity | 1 (3) |

| Interpersonal violence injury | 1 (3) |

| Pregnancy | 1 (3) |

| Selection for clinical condition, health care services, or both | |

| Clinical condition alone | 27(35) |

| Clinical condition and use of health care services | 11 (14) |

| Use of health care services | 19 (25) |

| Not specific to clinical condition or use of health care services | 20 (26) |

| Recruitment settingb | |

| Primary care | 27 (35) |

| Hospital (inpatient) | 17 (22) |

| Emergency department | 16 (21) |

| Outpatient clinic | 6 (8) |

| Recruited from health plan membership | 5 (6) |

| Telephone-based care | 4 (5) |

| Transitional housing | 3 (4) |

| Urgent care | 2 (3) |

| Web-based care | 0 (0) |

| Home-based care | 0 (0) |

| Other | 21 (27) |

| Not reported | 0 |

| Intervention settingb | |

| Primary care | 31 (44) |

| Home-based care | 27 (38) |

| Telephone-based care | 23 (32) |

| Hospital (inpatient) | 8 (11) |

| Transitional housing | 7 (10) |

| Outpatient clinic | 6 (8) |

| Emergency department | 4 (6) |

| Urgent care | 2 (3) |

| Web-based care | 2 (3) |

| Other | 17 (24) |

| Not reported | 6 (NA) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Studies may have reported addressing 1 or more of the prespecified social needs that were systematically captured. In addition, studies may have also reported that they addressed any need that arose in the population or social needs that were not prespecified.

Percentages add up to more than 100% because studies could have included participants in more than 1 age group, recruited from more than 1 setting, or have been conducted in more than 1 setting (eg, the group of studies with only older adults is also included in the group of studies with older adults).

Defined as more than 50%.

Studies included at least 1 specified or unspecified chronic condition.

Figure. Domains Addressed by Social Needs Interventions.

Based on 77 trials. The numbers along the diagonal represent the total number of studies addressing the domain. Numbers along the last row represent the number of studies addressing a single domain. Numbers between the diagonal and the last row represent the number of studies addressing both the domain in the row and the domain in the column. NA indicates not applicable.

Most studies (56 RCTs [73%]) included adults aged 18 years and older.36,37,38,39,42,44,45,46,48,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,69,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,101,103,104,106,108,109 Among the studies reporting race and ethnicity, studies most commonly included majority Black and non-Hispanic Black populations (24 RCTs [36%]).37,41,48,49,50,51,54,56,60,62,63,68,75,79,80,87,88,90,93,94,95,101,105,112 Almost one-half of the 77 studies (38 RCTs [49%]) required a health condition for inclusion in the intervention.37,40,43,46,49,50,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,63,64,67,68,73,75,79,80,82,83,88,89,91,92,93,94,96,97,99,101,105,107,108,109,112

Studies reported multiple recruitment settings, most commonly referrals from agencies or shelters, primary care, outpatient or inpatient care, or emergency department settings. Interventions were most often conducted in primary care, home-based settings, or via telephone.

Intensity and Complexity of Social Needs Interventions

eTable 18 in Supplement 1 characterizes the intensity and complexity of studies along multiple domains. Although reporting of planned intensity was inconsistent, 68 RCTs (88%) reported at least 1 feature suggestive of high intensity (≥8 contacts, ≥30 minutes per contact, frequency every 2 weeks or more often, duration ≥6 months, or home visits).36,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,98,100,101,102,103,104,106,107,108,109,110,111,112 Features of complexity (number of social needs addressed; whether or not a dedicated staff person mediated interactions between patients and the health care system; multiple practitioners, intervention components, behavior targets, resources offered to participants, or resources required to implement the program; and the ability to tailor the program) were more consistently reported than features of intensity. All studies reported at least 1 feature suggestive of complexity and 68 (88%) had 4 or more features that suggested complexity.36,37,38,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,108,112

Intensity

The number of planned participant contacts (either in person or via telephone, text, or mail) ranged from 139,70,97 to 2556 in the 35 studies (45%) that included these data.39,41,42,43,45,46,47,49,50,53,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,68,70,71,73,75,79,81,84,91,94,97,98,105,107,109,110,112 Intervention periods ranged from 2 weeks to 2 years. Planned contacts ranged from a single encounter to encounters at different intervals. Eight studies (10%) reported the planned duration of each contact, which ranged from 15 to 120 minutes.42,45,59,60,75,94,104,107 Twenty-six interventions (34%) included home visits, which presumably required a higher level of intensity to complete.40,41,43,46,47,48,49,57,61,68,71,72,73,74,75,76,79,83,85,87,89,95,101,108,111,112

Sixteen interventions (21%) reported on the actual number of contacts or their duration.36,40,41,46,61,62,77,84,87,89,98,101,102,106,110,112 The number of actual contacts (calls or text messages) ranged from 0 to 681. One intervention evaluating a care coordination intervention planned 24 contacts per participant, but the number of actual contacts ranged from 1 to 90.41 In 9 studies (12%) that reported on actual but not planned contacts, numbers ranged from no visits to a median of 79 care coordination activities or contacts per client.36,40,62,77,87,89,101,102,106

Complexity

Regardless of whether studies were attempting to address social needs alone or both medical and social needs, they generally aimed to change multiple participant behaviors. Only a minority expected to affect a single participant behavior (22 RCTs [29%]) (Table 2).38,39,42,44,45,55,59,61,63,64,66,68,70,82,86,92,95,97,105,106,109,111

Table 2. Intervention Features.

| Key question | Randomized clinical trials, No. (%) (N = 77) |

|---|---|

| 1: What is the intensity (eg, time, duration, or frequency) and complexity (eg, components and resources involved) of social needs interventions? | |

| Intensity | |

| Reported at least 1 feature indicating high intensity | |

| Yes | 68 (88) |

| No | 9 (12) |

| Reported any intensity feature | |

| Yes | 73 (95) |

| No | 4 (5) |

| Reported planned No. of contacts | |

| Yes | 35 (45) |

| NR | 42 (55) |

| Reported planned duration of contacts | |

| Yes | 8 (10) |

| NR | 69 (90) |

| Included home visits | |

| Yes | 26 (34) |

| No | 51 (66) |

| Reported data on actual No. of contacts or duration | |

| Yes | 16 (21) |

| No | 61 (79) |

| Complexity | |

| Reported any complexity feature | |

| Yes | 77 (100) |

| No | 0 |

| Level of complexity | |

| ≥4 Features suggesting complexity | 68 (88) |

| ≤3 Features suggesting complexity | 9 (12) |

| Behaviors or actions the intervention intended to address (modified iCAT-SR dimension 2), No. | |

| ≥3 | 40 (52) |

| 2 | 2 (3) |

| 1 | 22 (29) |

| Varies by patient needa | 13 (17) |

| Reported staff mediating patient–health system interaction | |

| Yes | 56 (73) |

| No | 21 (27) |

| Multiple practitioners involved | |

| Yes | 32 (43) |

| No | 42 (57) |

| NR | 3 (NA) |

| Practitionerb | |

| Health care practitioners (eg, doctors, nurses, or therapists) | 32 (43) |

| Community health workers and navigators | 31 (42) |

| Other nonprofessionals, including volunteers and study staff | 22 (30) |

| Social worker | 16 (22) |

| Case manager | 14 (19) |

| Lawyers | 2 (3) |

| NR | 3 (NA) |

| Intervention components (modified iCAT-SR dimension 1), No. | |

| >1 | 67 (87) |

| 1 | 10 (13) |

| Intervention component typeb | |

| Active assistance with resources (vouchers, appointment scheduling, or enrollment form help) | 62 (81) |

| Patient education (including on health, other social needs, or resources) | 47 (61) |

| Passive referrals | 28 (36) |

| Providing on-site resources | 21 (27) |

| Screening | 26 (34) |

| Health care practitioner education | 5 (6) |

| Intervention recipientb | |

| Patient | 66 (86) |

| Caregiver | 15 (19) |

| Physician or other clinical staff | 3 (4) |

| Community-based organizations | 1 (1) |

| Did the intervention provide resources for participants? | |

| Referrals to resources, practitioners, or other supports | 53 (69) |

| Information or educational materials, excluding referrals | 41 (53) |

| Other | 15 (19) |

| Supplies (eg, household items or monitoring devices) | 11 (14) |

| Transportation assistance | 11 (14) |

| Economic supports (eg, rent or utility assistance, nonfood vouchers, or money [excluding incentives for study participation]) | 8 (10) |

| Food (eg, food box or food voucher) | 7 (9) |

| No, the intervention did not include provision of resources | 3 (4) |

| Was tailoring, adaptation, or flexibility of the intervention intended? (modified iCAT-SR dimension 4) | |

| Yes, the intervention was tailored, could be adapted, and/or delivered flexibly | 63 (82) |

| No, the intervention was delivered to all in the same way | 10 (13) |

| Unclear or not stated | 4 (5) |

| Among interventions with tailoring, what was the degree of tailoring? (iCAT-SR dimension 4) (n = 63) | |

| Highly tailored or very flexible | 34 (54) |

| Moderately tailored or moderately flexible | 23 (37) |

| Minimally tailored or slightly flexible | 6 (10) |

| What was required to implement and/or deliver the intervention? | |

| Additional staff or nonstaff personnel (eg, community health workers, care coordinators, or peer mentors) | 69 (90) |

| Referral sources | 45 (58) |

| Time and/or space for visits or appointments (eg, added clinical visit, home visit, or telephone follow-up) | 43 (56) |

| Training for staff or nonstaff personnel | 38 (49) |

| Monetary or economic investment (not including existing available economic supports or incentives for participation) | 11 (14) |

| Other | 8 (10) |

| None | 1 (1) |

| 2: Can the effect of individual or combinations of intervention components on behavioral, health, or health care utilization outcomes be measured? | |

| How was the intervention or intervention components intended to be delivered? (iCAT dimension 1) | |

| >1 Component and some or all delivered as a bundle | 44 (57) |

| >1 Component; may be integrated into a package | 22 (29) |

| 1 Component | 11 (14) |

| Indicate the degree to which the effects of the intervention are dependent on the context or setting in which it is implemented. (iCAT-SR dimension 7) | |

| Highly dependent | 15 (19) |

| Moderately dependentc | 49 (64) |

| Independentd | 13 (17) |

| Unclear or unable to assess | 0 |

| Indicate the degree to which the effects of the intervention are changed by individual-level factors (ie, recipient or practitioner factors) (iCAT-SR dimension 9)e | |

| Highly dependent on individual-level factors | 51 (66) |

| Moderately dependent on individual-level factors | 23 (30) |

| Independent of individual-level factors | 3 (4) |

| Unclear or unable to assess | 0 |

Abbreviations: iCAT-SR, Intervention Complexity Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

When the intervention was designed to address varying patient needs, the number of behaviors or actions intended to be addressed may have varied.

Percentages add up to more than 100% because practitioner, intervention components, and intervention recipients were not mutually exclusive (eg, more than 1 practitioner could have provided an intervention).

The effects of the intervention are likely to be transferrable across a limited range of settings only (eg, only within a specific country or health system).

The effects of the intervention do not appear to be highly dependent on the implementation setting (ie, it is anticipated that the effects of the intervention will be similar across a wide range of contexts or settings).

Highly, the effects of the intervention were modified by both recipient and practitioner factors; moderately, the effects of the intervention were modified by 1 or more recipient or practitioner factors; independent, the effects of the intervention are not modified substantially by recipient or practitioner factors.

The majority of studies reported including staff (case managers, care coordinators, patient navigators, community health workers, promotoras, or peer navigators) who mediated interactions between patients and health and/or social care systems (56 RCTs [73%]).36,39,40,41,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,95,98,101,102,103,104,106,108,111,112 Seventy-four studies specified the type of intervention practitioner (74 RCTS [96%])36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,108,110,111,112; the majority of these 74 RCTs generally involved multiple practitioners (32 RCTs [43%]).37,38,41,45,46,51,52,53,54,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,69,71,74,76,77,81,82,87,89,91,92,95,99,101,105,108 Among the 74 studies reporting type of intervention practitioner, practitioners most frequently included health care practitioners (32 RCTs [43%]),37,38,41,45,46,51,52,53,54,57,58,59,60,61,63,66,71,74,77,82,84,87,89,91,92,95,99,100,101,105,108,110 community health workers (31 RCTs [42%]),36,37,38,39,40,42,46,48,49,50,54,56,57,59,61,62,67,68,72,73,76,85,87,88,91,92,95,98,101,102,108 and other non–health care professionals including volunteers and study staff (22 RCTs [30%]) (Table 2).37,43,44,45,53,58,60,63,64,69,70,71,80,81,86,94,96,99,103,105,108,111

Of the 77 RCTs, most included multiple components (67 RCTs [87%]).36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,98,99,100,101,102,104,105,106,107,108,112 Most frequently, these included active assistance (such as scheduling appointments or filling out forms) (62 RCTs [81%])38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,56,57,58,59,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,82,83,84,85,86,87,89,90,91,92,93,95,96,97,98,99,101,104,106,108,109,111,112 and patient education (47 RCTs [61%]).37,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,49,50,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,64,71,73,74,75,78,80,81,82,84,85,86,89,92,94,95,96,99,101,102,103,105,106,107,108,110,111,112 The component least commonly described was education of health care practitioners (5 RCTs [6%]).37,41,57,58,108

The vast majority of studies included provision of resources to participants (74 RCTs [96%]) as part of the intervention.36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,108,109,110,111,112 These interventions typically described offering multiple resources (median [IQR] 2 [1-2] resources); only 28 studies listed a single resource being offered to participants.36,42,50,51,56,67,68,70,78,79,80,82,83,84,87,89,91,92,93,94,97,100,103,106,108,109,111,112 The resources provided to participants included referrals to practitioners, resource agencies, or other supports (53 RCTs [69%])36,37,38,41,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,65,66,67,68,71,72,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,83,85,86,87,88,89,91,94,95,98,100,101,102,104,106,108; information or educational materials (41 RCTs [53%])37,40,41,42,44,46,48,49,52,55,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,66,70,71,72,73,74,75,77,81,84,85,86,88,96,98,99,101,102,103,104,105,110,111,112; supplies, such as clothing or allergen impermeable bedding (11 RCTs [14%])40,45,46,49,57,60,62,76,99,104,105; and transportation (11 RCTs [14%]).43,45,53,65,72,74,76,77,90,97,101 Fewer studies provided economic supports, such as vouchers (8 RCTs [10%])62,65,69,76,92,93,95,99 or food resources (7 RCTs [9%]).45,61,63,64,77,96,109

For each listed resource, the complexity of effort in providing the resource and the degree of tailoring the resources varied substantially. Table 3 lists examples of resources that varied in level of tailoring. Most of the 63 studies36,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,65,66,67,68,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,94,95,96,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,106,108,109,112 that noted tailored offerings also listed community health workers, navigators, or other personnel as key intermediaries in providing the resource (46 RCTs [73%]).36,41,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,65,66,67,68,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,82,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,95,98,101,102,103,104,106 Studies frequently described additional staffing needs to conduct interventions (69 RCTs [90%]).36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,98,100,101,102,103,104,106,108,109,110,111,112 Staffing included community health workers, practitioners, behavioral health specialists, care coordinators, social workers, peer navigators, and health educators, among others. Fewer studies explicitly described time or space requirements for interventions (43 RCTs [56%])38,41,42,43,45,46,48,49,50,51,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,64,66,67,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,86,87,88,89,90,91,94,101,102,103,104,107,108 or training needs for staff (38 RCTs [49%]).36,40,42,46,48,49,50,53,55,56,57,58,60,64,68,71,73,76,79,81,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,94,95,98,102,103,104,105,110,111,112 Training encompassed education on motivational interviewing, implicit bias, home assessment, care navigation, financial coaching, and specific conditions such as hypertension.

Table 3. Examples of Standardized Resources and Resources Tailored to Participant Needs.

| Resource type | Standardized resource examplea | Tailored resource example |

|---|---|---|

| Information materials (excluding referrals) | 20-min video about services42 | Coaches identified parent strengths and navigated participants to cost-saving services and public benefits104 |

| Economic supports | Subsidized housing95 | Funds loaned to cover apartment security deposit62 |

| Food | Biweekly fresh healthy foods61 | Home-delivered food boxes tailored to nutritional needs and ethnic food preferences every 2 weeks, for 24 weeks63 |

| Transportation assistance | Taxicab vouchers97 | Navigators helped patients access medical transportation assistance through the state Medicaid system53 |

| Supplies | Cell phones76 | Program staff helped clients obtain donated furniture and appliances62 |

| Referrals to resources or practitioners | Accompanied to clinic and introduced to care team45 | Interventionists provided referrals to other health center resources if indicated59 |

| Other | Free primary health care, radiology, and laboratory services38 | Pro bono legal services provided to families with specific legal needs54 |

Standardized resources may have initially been developed via sociocultural tailoring.

Measuring the Effects of Individual or Combinations of Intervention Components on Behavioral Outcomes, Health Outcomes, or Health Care Utilization Outcomes

All trials by design addressed overall effectiveness, but in most, the value of individual components could not be discerned by study design, analyses of components, or prior evidence. Regarding design, more than one-third of the interventions (27 RCTs [35%]) addressed both medical and social needs and compared them with usual care; these studies cannot speak to the effects of addressing social needs specifically.41,46,47,48,50,51,52,54,56,57,58,59,60,65,69,70,73,74,76,77,82,84,90,92,101,104,108 Only 4 studies (5%) compared usual care plus a single component addressing social needs with usual care alone; these studies directly address the causal effect of a single social needs intervention component.81,103,110,111 No study reported the use of multiphase optimization strategies.113

Regarding analyses of intervention components or characteristics, 13 studies (17%) planned or reported subanalyses (a priori or post hoc).36,37,45,57,59,71,79,86,89,92,96,98,106 Specifically, 1 study57 noted the infeasibility of randomizing all permutations of intervention components and described planned qualitative and quantitative approaches (implementation of components, mediator analyses, and perceptions of staff regarding effectiveness) to assess the effectiveness of components. One study45 reported on the results of a 2 × 2 factorial design. Eleven other studies reported on variations in outcomes by number of interactions, duration of interactions, or level of engagement or fidelity to planned interventions.36,37,59,71,79,86,89,92,96,98,106 The remaining majority (60 RCTs [78%]) were not designed or analyzed to address the effectiveness of intervention components. At the same time, the majority of interventions that did not plan or report subanalyses were moderately or highly dependent on context (51 RCTs [66%])38,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,48,49,51,52,53,54,56,58,60,61,62,64,65,66,67,70,72,73,74,75,76,78,80,82,83,84,85,87,88,90,91,93,94,95,99,100,101,102,103,107,108,111,112 and individual factors related to the patient or practitioner (61 RCTs [79%]).38,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,69,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,80,81,82,83,84,85,87,88,90,91,93,94,95,97,99,100,101,102,103,105,107,108,109,110,111,112 As a result, the effects of individual intervention components could not often be distinguished from the potential moderating effects of contextual factors. Finally, multicomponent studies rarely reported prior evidence (6 of 67 RCTs [9%]) to justify specific components (eTable 19 in Supplement 1),49,71,91,99,104,107 but often cited evidence for broad approaches, community needs, or prevalence of social needs as overall justification.

Discussion

The findings of this review of a scoping review suggest that the social needs interventions described in published RCTs are often both highly complex and intensive. Although high levels of intensity and complexity may be essential to meaningfully address complex social issues, some evidence suggests higher intensity interventions do not universally result in better health outcomes.114 The majority of the intervention studies included in this review did not report assessing (by design; mediator, moderator, or other analyses; or citing prior studies) how different intervention components independently modify health or utilization outcomes, thereby heightening the challenge of implementing and scaling these programs.

The underlying complexity and interaction of social risk factors, context, setting, and outcomes limit the generalizability of RCTs testing single or even multiple intervention components in factorial designs.114 To address challenges of replication and scalability, several recent systematic reviews have called for new primary research that employs economic evaluations,22 larger controlled and rigorous studies,18,25 and better descriptions of clinical integration19 and implementation.20 Future research also may be strengthened by using multiphase optimization strategies or sequential multiple assignment randomized trial designs to help isolate effective components of these complex interventions.113 In addition, hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs that concurrently assess both intervention effectiveness and implementation outcomes could shed light on how implementation is associated with intervention effectiveness.115 Systematic reviews employing qualitative synthesis, meta-regression, finite mixture models, or qualitative comparative analysis can also help identify features of complex and intense interventions most associated with beneficial outcomes.114 Not every combination of components is appropriate or feasible for evaluation; selecting appropriate combinations for further evaluation will require qualitative analyses and judgment and use of designs not commonly employed. These approaches may be appropriate when effectiveness is established, the intervention has widespread applicability, intervention components are designed and intended to be separable, and understanding the effects of individual components is relevant to policy and practice. However, these types of studies also require larger sample sizes, more resources, and more time. All types of social needs intervention studies would benefit from better and more consistent reporting standards.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, information on social determinants of health is evolving; our broad and comprehensive search terms may have been insufficient to capture all relevant studies and their ancillary publications. Our searches were restricted to studies published in the health services literature. As a result, we likely missed studies indexed solely in the social sciences or economics literature. We also excluded nonrandomized studies that may have provided insights on selected combinations of intervention components. Second, intervention rationale and design were not always clearly reported. As a result, our subjective decisions may have led us to inadvertently exclude relevant studies; dual independent review may have mitigated this concern to some extent. Third, this review of a scoping review excluded comparative effectiveness trials of social needs interventions that may have undertaken more granular comparisons. Fourth, we relied on intensity metrics based on modal values. Future studies should establish thresholds that correspond to workforce and participant expectations. Fifth, studies varied substantially in whether and how intensity and complexity were reported; as a result, patterns observed may at least in part reflect variations in reporting rather than intervention design. Sixth, we did not intend to synthesize and grade the evidence on specific outcomes; future syntheses should couple evaluations of intensity and complexity with intervention effectiveness.

Conclusions

Social needs interventions are typically complex, intense, and include multiple components. By design, RCTs of these interventions address overall effectiveness but are rarely designed to distinguish the causal effects of specific components, despite being resource intensive. Future studies with hybrid effectiveness-implementation or sequential designs and more standardized reporting of intervention intensity and complexity could help stakeholders assess the return on investment of these interventions.

eTable 1. Ovid MEDLINE® Search String and Yield for Access to Care MEDLINE Search (Ovid MEDLINE®) (April 6, 2023)

eTable 2. Cochrane Library (Including Both Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) Search String and Yield for Access to Care (April 6, 2023)

eTable 3. Ovid MEDLINE® Search String and Yield for Food Insecurity, Housing, Education and Literacy, Financial Strain, Employment, Transportation, Utilities, Social Isolation, Early Childhood Development, Legal Services, and Childcare (Ovid MEDLINE®) (April 6, 2023)

eTable 4. Cochrane Library (Including Both Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) Search String and Yield for Food Insecurity, Housing, Education and Literacy, Financial Strain, Employment, Transportation, Utilities, Social Isolation, Early Childhood Development, Legal Services, and Childcare (April 6, 2023)

eTable 5. Ovid MEDLINE® Search String and Yield for Interpersonal Violence MEDLINE Search (Ovid MEDLINE®) (April 6, 2023)

eTable 6. Cochrane Library (Including Both Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) Search String and Yield for Interpersonal Violence (April 6, 2023)

eTable 7. Ovid MEDLINE® Search String and Yield for Access to Care MEDLINE Search (Ovid MEDLINE®) (February 7, 2023)

eTable 8. Cochrane Library (Including Both Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) Search String and Yield for Access to Care (February 1, 2023)

eTable 9. Ovid MEDLINE® Search String and Yield for Food Insecurity, Housing, Education and Literacy, Financial Strain, Employment, Transportation, Utilities, Social Isolation, Early Childhood Development, Legal Services, and Childcare (Ovid MEDLINE®) (February 7, 2023)

eTable 10. Cochrane Library (Including Both Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) Search String and Yield for Food Insecurity, Housing, Education and Literacy, Financial Strain, Employment, Transportation, Utilities, Social Isolation, Early Childhood Development, Legal Services, and Childcare (February 1, 2023)

eTable 11. Ovid MEDLINE® Search String and Yield for Interpersonal Violence MEDLINE Search (Ovid MEDLINE®) (February 7, 2023)

eTable 12. Cochrane Library (Including Both Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) Search String and Yield for Interpersonal Violence (February 1, 2023)

eTable 13. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods. Identification of Social Needs

eFigure 1. Screening Approach

eResults. Identification of Social Needs

eTable 14. Risk of Bias Domains and Ratings

eTable 15. iCAT SR Dimensions, Assessment Categories, and Elaboration and Explanations

eTable 16. RCT Abstraction Form Items Adapted From iCAT

eFigure 2. Article Flow

eTable 17. Description of how Social Needs Were Identified

eTable 18. Measures of Intervention Intensity and Complexity

eTable 19. Justification of Intervention Components

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Health topics: social determinants of health. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- 2.Marmot MG, Rose G, Shipley M, Hamilton PJ. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978). 1978;32(4):244-249. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.4.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1387-1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(Suppl)(suppl):S8-S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381-398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97(2):407-419. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai D. Additional guidance on use of in lieu of services and settings in Medicaid managed care: SMD #23-001. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Published January 4, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-01/smd23001.pdf

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . All-state Medicaid and CHIP call. Published December 6, 2022. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/covid19allstatecall12062022.pdf

- 9.California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) . Medi-Cal transformation. Accessed December 13, 2023. https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/CalAIM/Pages/CalAIM.aspx

- 10.Gottlieb LM, DeSilvey SC, Fichtenberg C, Bernheim S, Peltz A. Developing national social care standards. Health Affairs. Published February 22, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/developing-national-social-care-standards

- 11.Cadet TJ, Golden R, Warren-Clem K. Integrating social needs care into the delivery of health care to improve the nation’s health for older adults. Innov Aging. 2019;3(suppl 1):S496-S497. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz038.1840 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley EH, Sipsma H, Taylor LA. American health care paradox-high spending on health care and poor health. QJM. 2017;110(2):61-65. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pruitt Z, Emechebe N, Quast T, Taylor P, Bryant K. Expenditure reductions associated with a social service referral program. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(6):469-476. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Edwards ST. Addressing health-related social needs: value-based care or values-based care? J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1916-1918. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05087-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Commonwealth Fund . Review of evidence for health-related social needs interventions. Published 2019. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/COMBINED-ROI-EVIDENCE-REVIEW-7-1-19.pdf

- 16.Fitzpatrick SL, Papajorgji-Taylor D. Social risk-informed care: scoping review and qualitative research to inform implementation at Kaiser Permanente. Published December 2021. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.kpwashingtonresearch.org/application/files/3516/4131/7338/Social-Risk-Informed-Care-Evaluation_Final-Report.pdf

- 17.Marchis EH, Aceves BA, Brown EM, Loomba V, Molina MF, Gottlieb LM. Assessing implementation of social screening within US health care settings: a systematic scoping review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(4):626-649. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.220401R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(5):719-729. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb LM, Garcia K, Wing H, Manchanda R. Clinical interventions addressing nonmedical health determinants in Medicaid managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):370-376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eder M, Henninger M, Durbin S, et al. Screening and interventions for social risk factors: technical brief to support the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1416-1428. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan AF, Chen Z, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of social needs screening and interventions in clinical settings on utilization, cost, and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):454-475. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnard LS, Wexler DJ, DeWalt D, Berkowitz SA. Material need support interventions for diabetes prevention and control: a systematic review. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(2):574. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0574-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gettel CJ, Voils CI, Bristol AA, et al. Care transitions and social needs: A Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research (GEAR) network scoping review and consensus statement. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(12):1430-1439. doi: 10.1111/acem.14360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little M, Rosa E, Heasley C, Asif A, Dodd W, Richter A. Promoting healthy food access and nutrition in primary care: a systematic scoping review of food prescription programs. Am J Health Promot. 2021;Published online December 10, 2021. doi: 10.1177/08901171211056584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyris J, Keller S, Parikh K. Social risk interventions and health care utilization for pediatric asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e215103. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welch V, Petticrew M, Petkovic J, et al. ; PRISMA-Equity Bellagio group . Extending the PRISMA statement to equity-focused systematic reviews (PRISMA-E 2012): explanation and elaboration. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:92. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0219-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welch V, Petticrew M, Tugwell P, et al. ; PRISMA-Equity Bellagio group . PRISMA-Equity 2012 extension: reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):e1001333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viswanathan M, Kennedy S, Eder M, et al. Social needs interventions to improve health outcomes. Published August 2021. Updated April 6, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/social-needs-interventions/index.html

- 30.Viswanathan M, Kennedy S, Sathe N, Eder M, Gottlieb L. Social needs interventions evidence map: systematic review protocol. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://osf.io/jhx7z/

- 31.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy people 2020. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. April 13, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://wayback.archive-it.org/5774/20220413182850/https:/www.healthypeople.gov/2020/

- 32.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy people 2030. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople

- 33.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE, Thomson HJ, Johnston RV, Thomas J. Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0. Cochrane; 2019. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6/chapter-03 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewin S, Hendry M, Chandler J, et al. Assessing the complexity of interventions within systematic reviews: development, content and use of a new tool (iCAT_SR). BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0349-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heisler M, Lapidos A, Kieffer E, et al. Impact on health care utilization and costs of a Medicaid community health worker program in Detroit, 2018–2020: a randomized program evaluation. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(5):766-775. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu AW, Weston CM, Ibe CA, et al. The Baltimore Community-Based Organizations Neighborhood Network: Enhancing Capacity Together (CONNECT) cluster RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(2):e31-e41. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackinney T, Visotcky AM, Tarima S, Whittle J. Does providing care for uninsured patients decrease emergency room visits and hospitalizations? J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(2):135-142. doi: 10.1177/2150131913478981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horwitz SM, Busch SH, Balestracci KM, Ellingson KD, Rawlings J. Intensive intervention improves primary care follow-up for uninsured emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(7):647-652. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieger J, Takaro TK, Song L, Beaudet N, Edwards K. A randomized controlled trial of asthma self-management support comparing clinic-based nurses and in-home community health workers: the Seattle-King County Healthy Homes II Project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(2):141-149. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623-2633. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilgeman MM, Mahaney-Price AF, Stanton MP, et al. ; Alabama Veterans Rural Health Initiative (AVRHI) Steering Committee . Alabama veterans rural health initiative: a pilot study of enhanced community outreach in rural areas. J Rural Health. 2014;30(2):153-163. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schumacher JR, Lutz BJ, Hall AG, et al. Feasibility of an ED-to-home intervention to engage patients: a mixed-methods investigation. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(4):743-751. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.2.32570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Brien GM, Stein MD, Fagan MJ, Shapiro MJ, Nasta A. Enhanced emergency department referral improves primary care access. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(10):1265-1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Borgia ML, Rose J. Tailoring outreach efforts to increase primary care use among homeless veterans: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):886-898. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3193-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger J, Song L, Philby M. Community health worker home visits for adults with uncontrolled asthma: the HomeBASE Trial randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):109-117. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bronstein LR, Gould P, Berkowitz SA, James GD, Marks K. Impact of a social work care coordination intervention on hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Work. 2015;60(3):248-255. doi: 10.1093/sw/swv016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, et al. Patient-centered community health worker intervention to improve posthospital outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):535-543. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams SG, Brown CM, Falter KH, et al. Does a multifaceted environmental intervention alter the impact of asthma on inner-city children? J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(2):249-260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Norton L, et al. Effect of community health worker support on clinical outcomes of low-income patients across primary care facilities: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1635-1643. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shumway M, Boccellari A, O’Brien K, Okin RL. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(2):155-164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liss DT, Ackermann RT, Cooper A, et al. Effects of a transitional care practice for a vulnerable population: a pragmatic, randomized comparative effectiveness trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1758-1765. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05078-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelley L, Capp R, Carmona JF, et al. Patient navigation to reduce emergency department (ED) utilization among Medicaid insured, frequent ED users: a randomized controlled trial. J Emerg Med. 2020;58(6):967-977. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bovell-Ammon A, Mansilla C, Poblacion A, et al. Housing intervention for medically complex families associated with improved family health: pilot randomized trial. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):613-621. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim SE, Michalopoulos C, Kwong RM, Warren A, Manno MS. Telephone care management’s effectiveness in coordinating care for Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care: a randomized controlled study. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(5):1730-1749. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Huo H, Smith RA, Long JA. Community health worker support for disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic diseases: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1660-1667. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Towfighi A, Cheng EM, Ayala-Rivera M, et al. ; Secondary Stroke Prevention by Uniting Community and Chronic Care Model Teams Early to End Disparities (SUCCEED) Investigators . Effect of a coordinated community and chronic care model team intervention vs usual care on systolic blood pressure in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: the SUCCEED Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036227. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duncan PW, Bushnell CD, Jones SB, et al. ; COMPASS Site Investigators and Teams. . Randomized pragmatic trial of stroke transitional care: the COMPASS Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(6):e006285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talavera GA, Castañeda SF, Mendoza PM, et al. Latinos understanding the need for adherence in diabetes (LUNA-D): a randomized controlled trial of an integrated team-based care intervention among Latinos with diabetes. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(9):1665-1675. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nyamathi A, Flaskerud JH, Leake B, Dixon EL, Lu A. Evaluating the impact of peer, nurse case-managed, and standard HIV risk-reduction programs on psychosocial and health-promoting behavioral outcomes among homeless women. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(5):410-422. doi: 10.1002/nur.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrer RL, Neira LM, De Leon Garcia GL, Cuellar K, Rodriguez J. Primary care and food bank collaboration to address food insecurity: a pilot randomized trial. Nutr Metab Insights. 2019;12:Published online July 29, 2019. doi: 10.1177/1178638819866434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toro PA, Passero Rabideau JM, Bellavia CW, et al. Evaluating an intervention for homeless persons: results of a field experiment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(3):476-484. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.3.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kempainen S, Cutts DB, Robinson-O’Brien R, De Kesel Lofthus A, Gilbertson DT, Mino R. A collaborative pilot to support patients with diabetes through tailored food box home delivery. Health Promot Pract. 2023;24(5):963-968. doi: 10.1177/15248399221100792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bryce R, WolfsonBryce JA, CohenBryce A, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a fruit and vegetable prescription program at a federally qualified health center in low income uncontrolled diabetics. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101410. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wagner V, Sy J, Weeden K, et al. Effectiveness of intensive case management for homeless adolescents: results of a 3-month follow-up. J Emot Behav Disord. 1994;2(4):219-227. doi: 10.1177/106342669400200404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sood RK, Bae JY, Sabety A, Chan PY, Heindrichs C. ActionHealthNYC: effectiveness of a health care access program for the uninsured, 2016–2017. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(7):1318-1327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balaban RB, Zhang F, Vialle-Valentin CE, et al. Impact of a patient navigator program on hospital-based and outpatient utilization over 180 days in a safety-net health system. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(9):981-989. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4074-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krieger J, Collier C, Song L, Martin D. Linking community-based blood pressure measurement to clinical care: a randomized controlled trial of outreach and tracking by community health workers. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(6):856-861. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.6.856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raven MC, Niedzwiecki MJ, Kushel M. A randomized trial of permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless persons with high use of publicly funded services. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(Suppl 2)(suppl 2):797-806. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Birkhead GS, LeBaron CW, Parsons P, et al. The immunization of children enrolled in the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): the impact of different strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(4):312-316. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530040040038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng TL, Haynie D, Brenner R, Wright JL, Chung SE, Simons-Morton B. Effectiveness of a mentor-implemented, violence prevention intervention for assault-injured youths presenting to the emergency department: results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):938-946. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin MP, Blanchfield BB, Kakoza RM, et al. ED-based care coordination reduces costs for frequent ED users. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(12):762-766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ell K, Aranda MP, Wu S, Oh H, Lee PJ, Guterman J. Promotora assisted depression and self-care management among predominantly Latinos with concurrent chronic illness: safety net care system clinical trial results. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;61:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Ezeji-Okoye SC, et al. Effect of an intensive outpatient program to augment primary care for high-need Veterans Affairs patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):166-175. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kneipp SM, Kairalla JA, Lutz BJ, et al. Public health nursing case management for women receiving temporary assistance for needy families: a randomized controlled trial using community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1759-1768. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown DM, Hernandez EA, Levin S, et al. Effect of social needs case management on hospital use among adult Medicaid beneficiaries: a randomized study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(8):1109-1117. doi: 10.7326/M22-0074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Henschen BL, Theodorou ME, Chapman M, et al. An intensive intervention to reduce readmissions for frequently hospitalized patients: the CHAMP randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):1877-1884. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07048-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Post B, Lapedis J, Singh K, et al. Predictive model-driven hotspotting to decrease emergency department visits: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(9):2563-2570. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06664-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tomita A, Herman DB. The impact of critical time intervention in reducing psychiatric rehospitalization after hospital discharge. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(9):935-937. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Herman D, Opler L, Felix A, Valencia E, Wyatt RJ, Susser E. A critical time intervention with mentally ill homeless men: impact on psychiatric symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(3):135-140. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200003000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lopez MA, Yu X, Hetrick R, et al. Social needs screening in hospitalized pediatric patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hosp Pediatr. 2023;13(2):95-114. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2022-006815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lipton FR, Nutt S, Sabatini A. Housing the homeless mentally ill: a longitudinal study of a treatment approach. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):40-45. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Korr WS, Joseph A. Housing the homeless mentally ill: findings from Chicago. J Soc Serv Res. 1995;21(1):53-68. doi: 10.1300/J079v21n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hannan J, Brooten D, Page T, Galindo A, Torres M. Low-income first-time mothers: effects of APN follow-up using mobile technology on maternal and infant outcomes. Glob Pediatr Health. 2016;3:X16660234. doi: 10.1177/2333794X16660234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carter J, Hassan S, Walton A, Yu L, Donelan K, Thorndike AN. Effect of community health workers on 30-day hospital readmissions in an accountable care organization population: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110936. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(11):e162521. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sege R, Preer G, Morton SJ, et al. Medical-legal strategies to improve infant health care: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):97-106. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Corrigan PW, Kraus DJ, Pickett SA, et al. Using peer navigators to address the integrated health care needs of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(3):264-270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dixon L, Goldberg R, Iannone V, et al. Use of a critical time intervention to promote continuity of care after psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):451-458. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(17):1771-1778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Waitzkin H, Getrich C, Heying S, et al. Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: a multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. J Community Health. 2011;36(2):316-331. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9313-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burnam MA, Morton SC, McGlynn EA, et al. An experimental evaluation of residential and nonresidential treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Addict Dis. 1995;14(4):111-134. doi: 10.1300/J069v14n04_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.O’Connell M, Sint K, Rosenheck R. How do housing subsidies improve quality of life among homeless adults? A mediation analysis. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;61(3-4):433-444. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McClintock HF, Bogner HR. Incorporating patients’ social determinants of health into hypertension and depression care: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(6):703-710. doi: 10.1007/s10597-017-0131-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shinn M, Samuels J, Fischer SN, Thompkins A, Fowler PJ. Longitudinal impact of a family critical time intervention on children in high-risk families experiencing homelessness: a randomized trial. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;56(3-4):205-216. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9742-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berkowitz SA, O’Neill J, Sayer E, et al. Health center-based community-supported agriculture: an RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6)(suppl 1):S55-S64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Melnikow J, Paliescheskey M, Stewart GK. Effect of a transportation incentive on compliance with the first prenatal appointment: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(6):1023-1027. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00147-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gottlieb LM, Adler NE, Wing H, et al. Effects of in-person assistance vs personalized written resources about social services on household social risks and child and caregiver health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200701. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Andrews KG, Martin MW, Shenberger E, Pereira S, Fink G, McConnell M. Financial support to Medicaid-eligible mothers increases caregiving for preterm infants. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(5):587-600. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-02905-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mion LC, Palmer RM, Meldon SW, et al. Case finding and referral model for emergency department elders: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(1):57-68. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Finkelstein A, Zhou A, Taubman S, Doyle J. Health care hotspotting—a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(2):152-162. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1906848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Eismann EA, Zhang B, Fenchel M, et al. Impact of screening and co-located parent coaching within pediatric primary care on child health care use: a stepped wedge design. Prev Sci. 2023;24(1):173-185. doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01447-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Johnson EM, Poleshuck E, Possemato K, et al. Practical and emotional peer support tailored for life’s challenges: personalized support for progress randomized clinical pilot trial in a Veterans Health Administration Women’s Clinic. Mil Med. 2022;7-8(188):1600-1608. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usac164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schickedanz A, Perales L, Holguin M, et al. Clinic-based financial coaching and missed pediatric preventive care: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2023;151(3):e2021054970. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-054970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guevara JP, Erkoboni D, Gerdes M, et al. Effects of early literacy promotion on child language development and home reading environment: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr X. 2020;2:100020. doi: 10.1016/j.ympdx.2020.100020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cox GB, Walker RD, Freng SA, Short BA, Meijer L, Gilchrist L. Outcome of a controlled trial of the effectiveness of intensive case management for chronic public inebriates. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59(5):523-532. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Theeke LA, Mallow JA, Moore J, McBurney A, Rellick S, VanGilder R. Effectiveness of LISTEN on loneliness, neuroimmunological stress response, psychosocial functioning, quality of life, and physical health measures of chronic illness. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;3(3):242-251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Caskey R, Moran K, Touchette D, et al. Effect of comprehensive care coordination on Medicaid expenditures compared with usual care among children and youth with chronic disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912604. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Berkowitz SA, Delahanty LM, Terranova J, et al. Medically tailored meal delivery for diabetes patients with food insecurity: a randomized cross-over trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):396-404. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4716-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.High PC, LaGasse L, Becker S, Ahlgren I, Gardner A. Literacy promotion in primary care pediatrics: can we make a difference? Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 2):927-934. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.S3.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Flores G, Lin H, Walker C, et al. Parent mentoring program increases coverage rates for uninsured Latino children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(3):403-412. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lumba-Brown A, Batek M, Choi P, Keller M, Kennedy R. Mentoring pediatric victims of interpersonal violence reduces recidivism. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35(21-22):4262-4275. doi: 10.1177/0886260517705662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]