Significance

RNA interference is the primary antiviral defense in plants, fungi, and invertebrates, wherein Dicer cleaves viral dsRNA (double-stranded RNA) into siRNAs (small-interfering RNA), while Argonaute as the effector digests target viral RNA using virus-derived guide siRNAs. However, an interesting question remains unanswered; Does Dicer alone play an antiviral role in the absence of Argonaute? This question is difficult to answer because disruption of all members of the Argonaute family would lead to lethality. Herewith we addressed this long-standing question by preparing a suite of single and multiple Dicer and Argonaute mutants of a model filamentous host fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica. We demonstrated Dicer-alone defense—the dispensability of Argonaute in antiviral defense—against some RNA viruses, while Argonaute is required for full-scale antiviral defense against others.

Keywords: RNAi, Argonaute, Dicer, fungal virus, chestnut blight

Abstract

Antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) is conserved from yeasts to mammals. Dicer recognizes and cleaves virus-derived double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and/or structured single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) into small-interfering RNAs, which guide effector Argonaute to homologous viral RNAs for digestion and inhibit virus replication. Thus, Argonaute is believed to be essential for antiviral RNAi. Here, we show Argonaute-independent, Dicer-dependent antiviral defense against dsRNA viruses using Cryphonectria parasitica (chestnut blight fungus), which is a model filamentous ascomycetous fungus and hosts a variety of viruses. The fungus has two dicer-like genes (dcl1 and dcl2) and four argonaute-like genes (agl1 to agl4). We prepared a suite of single to quadruple agl knockout mutants with or without dcl disruption. We tested these mutants for antiviral activities against diverse dsRNA viruses and ssRNA viruses. Although both DCL2 and AGL2 worked as antiviral players against some RNA viruses, DCL2 without argonaute was sufficient to block the replication of other RNA viruses. Overall, these results indicate the existence of a Dicer-alone defense and different degrees of susceptibility to it among RNA viruses. We discuss what determines the great difference in susceptibility to the Dicer-only defense.

Antiviral RNA silencing or RNA interference (RNAi) is a small RNA–mediated defense mechanism that has been conserved from unicellular yeasts to multicellular mammals (1–4). Viral double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) or structured single-stranded RNAs (ssRNAs) are sensed and digested by the dsRNA-specific ribonuclease Dicer into small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which then serve as a guide and enhance the degradation and translational repression of target viral RNAs by the effector ribonuclease Argonaute (5, 6). In plants and nematodes, host-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDR) is involved in the amplification cycle of siRNA production (5, 7). Therefore, deficiency of these key genes in the RNAi antiviral pathway results in enhanced virus replication and symptom induction (8–11). One of the important unanswered questions about antiviral RNAi is whether Dicer activity without Argonaute effectors is functional in antiviral defense. Although this issue has been discussed previously (12), no conclusions have been drawn. This question can be tested only by disrupting all Argonaute genes in an organism. In plants and animals, however, multiple knockouts of all Argonaute genes could be difficult because of the great numbers of paralogous Argonaute genes, several of which are involved in the microRNA (miRNA) pathway crucial for development (13, 14). For example, the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana has 10 (15), human has eight (16), the model fly Drosophila melanogaster has five (17), and the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has 27 Argonaute paralogs (18), which show pleiotropic roles.

The chestnut blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, is a destructive plant pathogen as well as a filamentous model fungus for studying virus–virus and virus–host interactions (19, 20). This ascomycetous fungus has two dicer-like (dcl1 and dcl2), four argonaute-like (agl1 to agl4), and four rdr (rdr1 to rdr4) genes (10, 21, 22). By utilizing the prototype ssRNA monopartite hypovirus Cryphonectria hypovirus 1 (CHV1) with a capsidless nature, researchers have shown that dcl2 and agl2 are required for antiviral RNAi (10, 21). Unlike in plants, no rdr gene in C. parasitica is involved in antiviral RNAi, indicating that no amplification step of siRNA is required for it (22); instead, transcription of the key genes dcl2 and agl2 is markedly induced upon virus infection (21, 23). The mechanisms governing these regulations are largely unknown. Another unique feature of C. parasitica is that DCL2 plays a dual role transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally. As observed in other organisms, DCL2 functions as one of the key RNAi genes to dice viral dsRNAs (10, 24). In addition, DCL2 serves as a positive feedback player to transcriptionally induce many host genes, including dcl2 and agl2, an action that requires the general transcriptional coactivator SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase) complex (25, 26). This transcriptional regulation can be suppressed by a viral RNA silencing suppressor (RSS), such as CHV1 p29, via an unknown mechanism (21, 25, 27). Some of the up-regulated host genes alleviate virus symptoms without affecting virus replication, leading researchers to propose an additional layer of host defense (symptom mitigation) (25). We have previously shown that the highly induced RNAi state, either by an infecting virus or transgenic expression of dsRNA, can eliminate a preexisting heterologous dsRNA virus, Rosellinia necatrix victorivirus 1 (RnVV1) with an undivided, encapsidated dsRNA genome (23). Surprisingly, dcl2 but not agl2 is required for elimination or clearance of this virus. There are two possibilities to explain this phenomenon: 1) agl genes other than agl2 function as an effector of antiviral RNAi and 2) DCL2 is sufficient for virus interference.

In the current study, we show Dicer-dependent, Argonaute-independent RNAi in C. parasitica against multiple RNA viruses such as RnVV1, and the different levels of susceptibility to this Dicer-only antiviral defense among RNA viruses. We found this by preparing a suite of deletion mutants lacking single or multiple agl genes with or without dcl disruption.

Results

Establishment and Phenotypes of dcl/agl Single and Multiple Knockout C. parasitica Strains.

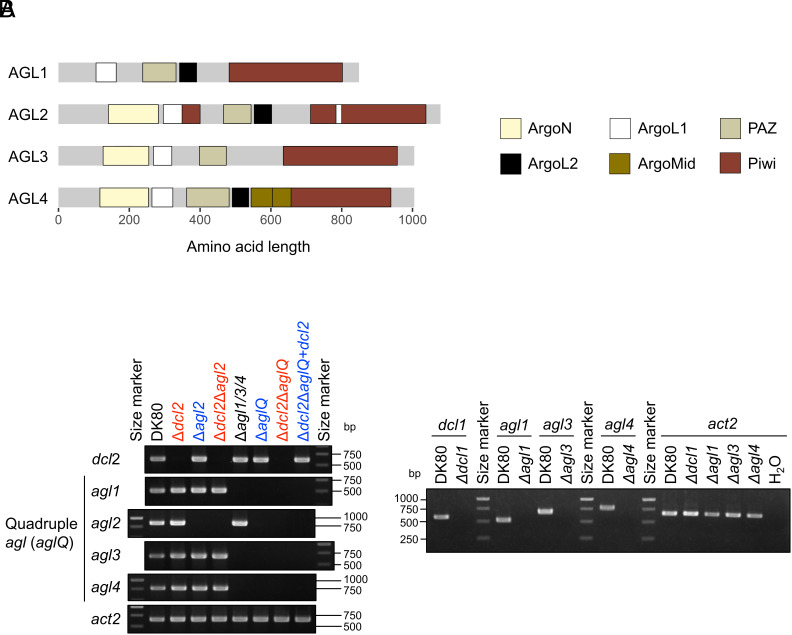

Although the function of C. parasitica agl1, agl3, and agl4 remains unknown, all of them, in addition to agl2, encode typical Argonaute domains (28) (Fig. 1A). We first prepared single and multiple agl disruptants, including a triple agl mutant (Δagl1/3/4) and a quadruple agl mutant (ΔaglQ), in C. parasitica strain DK80 with or without the other key RNAi gene dcl2 disrupted (see Table 1 for names and genotypes of all the mutants). Strain DK80 is an EP155 (a wild-type strain) mutant that lacks a ku80 ortholog (cpku80, required for nonhomologous end-joining DNA repair) to increase homologous recombination (HR) efficiency (29). We replaced the coding sequence of dcl/agl genes with selectable marker genes (SMGs, antibiotic resistance genes) by HR (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). For multiple gene disruption, we utilized three SMGs and a Cre-loxP-mediated marker recycling system, in which Cre recombinase catalyzed loxP site-specific recombination to remove SMGs (30) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). In all the generated mutants, we validated precise target disruption by PCR and Southern blotting (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Importantly, all the dcl/agl disruptants manifested a normal growth phenotype on potato dextrose agar plates, similarly to the original strain DK80 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 1.

Disruption of Argonaute-like protein genes (agl) with Dicer-like protein genes (dcl) in C. parasitica. (A) Four Argonaute-like proteins (AGLs) of C. parasitica DK80, a ku80-deletion mutant of a reference strain EP155. These AGLs collectively include six typical Argonaute domains, namely Argonaute linker 1 domain (ArgoL1), Argonaute linker 2 domain (ArgoL2), mid domain of Argonaute (ArgoMid), N-terminal domain of Argonaute (ArgoN), PAZ domain (PAZ), and Piwi domain (Piwi) (Pfam accession: PF08699.13, PF16488.8, PF16487.8, PF16486.8, PF02170.25, and PF02171.20, respectively). (B) Single or multiple deletions of dicer-like protein genes (dcl1 and dcl2) and/or argonaute-like protein genes (agl1, agl2, agl3, and agl4), validated by PCR. The strain names of C. parasitica mutants lacking dcl2 are displayed in red, while those lacking agl2 but possessing dcl2 are shown in blue in the Left panel. Other single mutants (Δdcl1, Δagl1, Δagl3, and Δagl4) are shown in the Right panel. Agarose gels were stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr). The PCR targets regions removed by HR within two dcl and four agl genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). An actin homolog gene (act2, encoding centractin ortholog) was detected as a positive control of PCR templates (genomic DNA of each fungal strain). Expected amplicon sizes from the intact genes are provided in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Table 1.

Viral and fungal strains used in this study*

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Viral | ||

| CHV1 | Nonsegmented, positive-sense RNA virus (12,734 nt) in the genus Alphahypovirus in the family Hypoviridae, from C. parasitica strain EP713 | (31) |

| RnVV1 | Nonsegmented dsRNA virus (5,329 bp) in the genus Victorivirus in the family Pseudototiviridae, from R. necatrix strain W1029 | (32) |

| MyRV1 | Eleven-segmented dsRNA virus (732 to 4,127 bp segments) in the genus Mycoreovirus in the family Spinareoviridae, from C. parasitica strain 9B21 | (33) |

| MyRV2 | Eleven-segmented dsRNA virus‡ in the genus Mycoreovirus in the family Spinareoviridae, from C. parasitica strain C18 | (34) |

| CHV1-Δp69 | A CHV1 mutant lacking ORFA that encodes p69, a precursor of RSS p29 | (35) |

| Fungal | ||

| EP155 | A standard virus-free strain of C. parasitica | (36) |

| EP155/CHV1 | C. parasitica EP155 inoculated with CHV1 isolate EP713 | (37) |

| EP155Δdcl2/RnVV1 | C. parasitica EP155 Δdcl2 inoculated with RnVV1 isolate W1029 | (32) |

| EP155/MyRV1 | C. parasitica EP155 inoculated with MyRV1 isolate 9B21 | (38) |

| EP155Δdcl2/MyRV2 | C. parasitica EP155 Δdcl2 inoculated with MyRV2 isolate C18 | This study |

| EP155/CHV1-Δp69 | C. parasitica EP155 inoculated with CHV1-Δp69 | (35) |

| DK80 | cpku80 knockout strain in C. parasitica EP155 background | (29) |

| Δdcl1† | dcl1 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δdcl2† | dcl2 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δagl1† | agl1 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δagl2† | agl2 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δagl3† | agl3 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δagl4† | agl4 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δdcl2Δagl2 | dcl2 and agl2 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δagl1/3/4 | agl1, agl3, and agl4 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| ΔaglQ | Quadruple agl (agl1 to agl4) knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 background | This study |

| Δdcl2ΔaglQ | dcl2 knockout strain in C. parasitica DK80 ΔaglQ background | This study |

| Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2 | dcl2 complementation strain of C. parasitica DK80 Δdcl2ΔaglQ | This study |

*Viral and fungal strains used only in supplementary data are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3.

†Knockout strains newly generated in DK80 background, different from the previously generated ones in EP155 background (10, 21).

‡The sequence of dsRNA3 (3,213 bp) is available in GenBank (accession: DQ902580).

DCL2 But Not Any Single AGL Efficiently Restricts RnVV1.

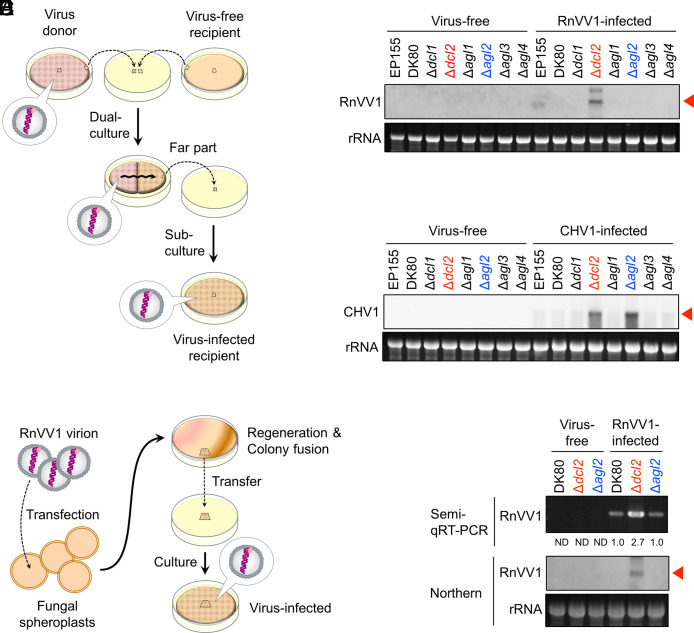

First, we analyzed RnVV1 accumulation, together with CHV1 accumulation in parallel, in the single dcl/agl knockout DK80 mutant series, namely Δdcl1, Δdcl2, Δagl1, Δagl2, Δagl3, and Δagl4 (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These mutants, DK80, and EP155 were each cocultured with respective virus donor fungal strains (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). We detected viral RNA in the virus-free or virus-infected recipients by northern hybridization using virus-specific complementary DNA probes against regions inside part encoding viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) (SI Appendix, Table S2). The northern hybridization showed clear RnVV1 signal only in Δdcl2 and none in EP155, DK80, Δdcl1, Δagl1, Δagl2, Δagl3, or Δagl4, after RnVV1-infection (Fig. 2B). Compared with EP155 and DK80, CHV1 accumulation was clearly increased in Δdcl2 and Δagl2, but not in Δdcl1, Δagl1, Δagl3, or Δagl4 (Fig. 2C). These CHV1 results are consistent with the previous results with the EP155 genetic background (10, 21). Recipient strains have been reported to carry over a minor portion of a donor’s karyons (32). To eliminate the possibility of heterokaryon effects on RnVV1 accumulation, we next transfected DK80, Δdcl2, and Δagl2 with purified RnVV1 virions (Fig. 2D). Semiquantitative RT (semi-qRT)-PCR using a constant amount of substrate RNA showed that RnVV1 was accumulated comparably in DK80 and Δagl2, while there was more in Δdcl2 transfectants (Fig. 2E). Northern hybridization also showed clear RnVV1 signal only in Δdcl2, and none in DK80 or Δagl2 in the transfectants (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Viral RNA accumulation in the dcl/agl single knockout strains of C. parasitica. (A) The viral inoculation method via hyphal fusion. For the detailed procedure, refer to the Materials and Methods section. (B and C) Detection of RnVV1 (B) or CHV1 (C) RNA in virus-free or virus-infected fungal mycelia by northern hybridization. Each virus was inoculated via hyphal fusion. Northern hybridization was carried out with crude RNA enriched with ssRNA by lithium chloride (LiCl). In all northern hybridization, host ribosomal RNA (rRNA) with ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining is shown as a loading control. CHV1 was detected with a probe targeting a region lost in the major CHV1 DI RNA (39). Red arrows indicate the position of viral full-length mRNA and/or genomic RNA. (D) Viral inoculation for a heterologous virus (RnVV1) via virion transfection. For the detailed procedure, refer to the Materials and Methods section. (E) Detection of RnVV1 RNA in virus-free or RnVV1-infected fungal mycelia by semi-qRT-PCR and northern hybridization with LiCl-precipitated ssRNA fractions. RnVV1 was inoculated by virion transfection. Relative band intensity values for semi-qRT-PCR are shown below the electrophoretic image. ND stands for not determined/detected.

Taken together, these results indicate that dcl2 alone is responsible for RnVV1 reduction, while disruption of dcl1, agl1, agl2, agl3, or agl4 did not allow enhanced RnVV1 replication, suggesting that agl genes function redundantly or no agl genes are involved in the anti-RnVV1 response in C. parasitica. By contrast, both dcl2 and agl2 are required for CHV1 repression, as reported previously with the C. parasitica EP155 genetic background (10, 21).

A C. parasitica Reovirus MyRV2 Is Also Strongly Silenced by dcl2 But Not by agl2.

Researchers initially assumed that the susceptibility of RnVV1 to the Dicer-alone defense was associated with its poor adaptability to the host fungus C. parasitica, a nonnative host of RnVV1. RnVV1 is from another ascomycetous phytopathogen, R. necatrix (32). Thus, we screened a collection of viruses, which were originally isolated from C. parasitica, for those with RnVV1-like behaviors, namely restricted by dcl2, but not agl2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The tested C. parasitica viruses include three hypoviruses (a capsidless monopartite ssRNA genome) and two mycoreoviruses (a multisegmented, monoparticulate dsRNA genome), namely Cryphonectria hypovirus 2 (CHV2), Cryphonectria hypovirus 3 (CHV3), Cryphonectria hypovirus 4 (CHV4), mycoreovirus 1 (MyRV1), and mycoreovirus 2 (MyRV2) (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Table S3). We used these viruses to inoculate DK80 and its single and multiple mutants Δdcl2, Δagl2, and Δdcl2Δagl2 via hyphal fusion (Fig. 2A). We detected viral RNA in the recipient strains before and after the infection by using northern hybridization with probes targeting viral RdRP-encoding segments (SI Appendix, Table S2). CHV2, CHV3, CHV4, and MyRV1 obviously accumulated in DK80 and showed slight or no increase in Δdcl2, Δagl2, and a double mutant Δdcl2Δagl2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). In contrast, we did not detect MyRV2 in DK80 and Δagl2, but it highly accumulated in Δdcl2 and Δdcl2Δagl2, similarly to RnVV1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Thus, we subsequently investigated the possibility of Argonaute-independent antiviral silencing using RnVV1 and MyRV2.

Argonaute-Independent, Dicer-Dependent Defense against RnVV1 and MyRV2.

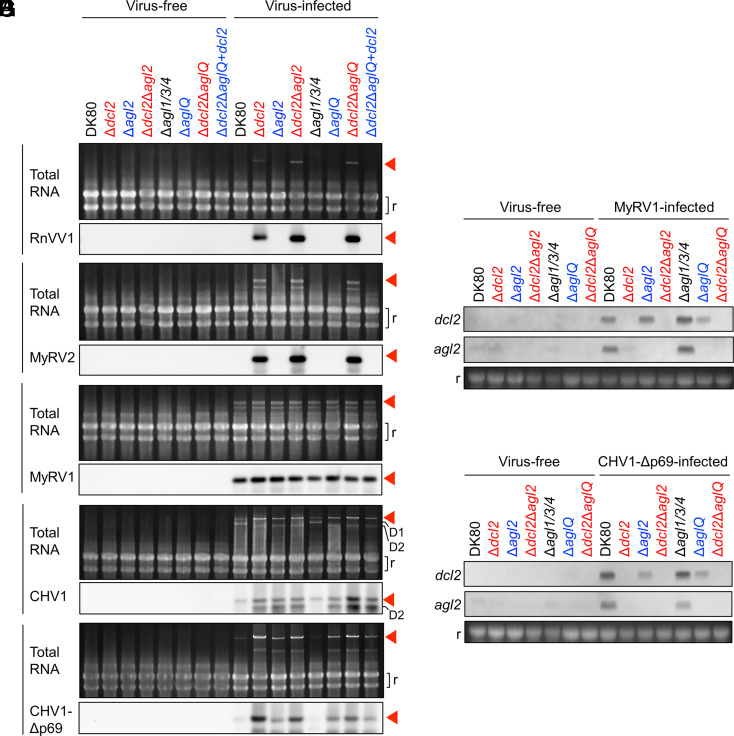

To test the possible functional redundancy of agl genes in the anti-RnVV1 and MyRV2 defense, we analyzed the antiviral ability of a subset of single to multiple dcl2/agl knockout C. parasitica strains and a dcl2-complemented strain for Δdcl2ΔaglQ (Fig. 3). We inoculated each fungal strain with each virus alone via hyphal fusion (Fig. 2A). We electrophoresed total RNA (viral and host ssRNA and dsRNA) purified from virus-free and virus-infected strains, stained it with ethidium bromide (EtBr) (Fig. 3 A–E, Upper), and subjected it to northern hybridization with probes targeting a viral RdRP-encoding region (Fig. 3 A–E, Lower).

Fig. 3.

Viral RNA accumulation and dcl2/agl2 induction in the dcl2/agl single and multiple knockout strains of C. parasitica. (A–E) Detection of viruses in total RNA extracted from the host strains. Each of RnVV1 (A), MyRV2 (B), MyRV1 (C), CHV1 (D), and CHV1-Δp69 (E) was inoculated to the fungal strains, and the respective viruses were detected in parallel with virus-free fungal strains as negative controls. For each of (A–E), the Upper row indicates fungal total RNA (DNase-treated total nucleic acids) with or without viral RNA detected by ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining, while the Lower row of each panel indicates the blots with viral signals detected by northern hybridization of the total RNA. The fungal strains lacking dcl2 are indicated with red. The fungal strains lacking agl2 but possessing dcl2 are indicated with blue. The other fungal strains are indicated with black. Same for the following panels (F and G). The red arrow indicates the position of the genome or its replicative form dsRNA of nonsegmented viruses (RnVV1, CHV1, and CHV1-Δp69) or the RdRP-encoding segment of multisegmented viruses (MyRV1 and MyRV2, the smaller viral bands are the other segments). The letter “r” indicates fungal rRNA bands as internal loading controls. “D1,” and “D2” represent an RNAi-dependent DI RNA (39) and an RNAi-independent defective RNA of CHV1, respectively. (F and G) Detection of dcl2/agl2 mRNA by northern hybridization with LiCl-precipitated RNA fractions. To test the induction of dcl2 and agl2 in the respective fungal strains upon virus infection, we used MyRV1 (F) or CHV1-Δp69 (G) which are known to induce dcl2 and agl2 expression in wild-type fungal strains. Host rRNA (r) is shown as a loading control.

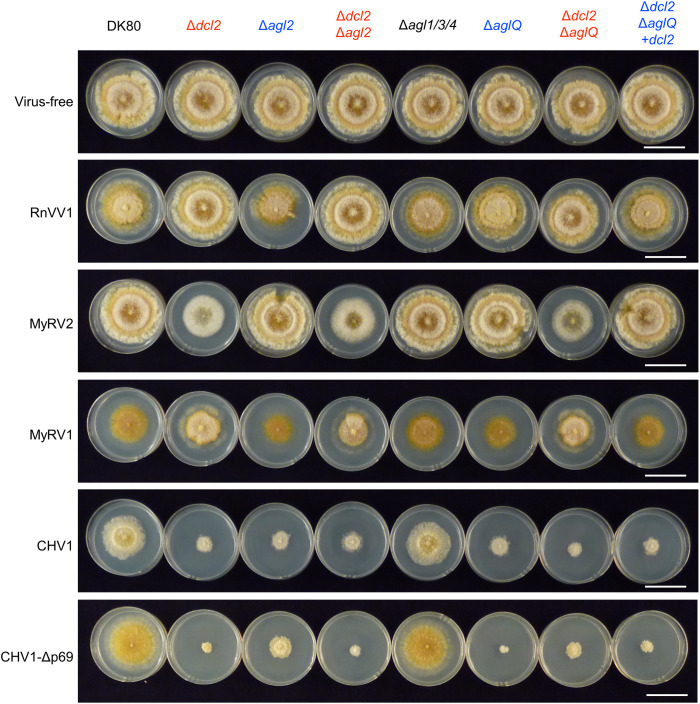

RnVV1 and MyRV2 were highly accumulated in the mutants lacking dcl2 (Δdcl2, Δdcl2Δagl2, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ) at a level detectable by EtBr (less sensitive), which we confirmed by northern hybridization (more sensitive), but not in DK80 and the other mutants lacking only agl genes (Δagl2, Δagl1/3/4, and ΔaglQ) (Fig. 3 A and B). DCL2-dependent, AGL-independent restriction of these two dsRNA viruses is supported by the observation that transgenic supply of dcl2 restored the virus restriction phenotype in the Δdcl2ΔaglQ background (Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2) (Fig. 3 A and B). We also performed real-time qRT-PCR and semi-qRT-PCR in the same total RNA samples. We detected RnVV1 and MyRV2 in all the recipients after virus inoculation, but the signals were stronger in the mutants lacking dcl2 than in DK80 and the other mutants, which was more obvious for MyRV2 than for RnVV1 (over two orders of magnitude for RnVV1 and four orders of magnitude for MyRV2) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The difference in semi-qRT-PCR signals between DK80 and the mutants lacking only agl genes was not associated with the presence or absence of particular agl genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). We obtained similar results by qRT-PCR, northern hybridization, and semi-qRT-PCR using ssRNA-enriched fraction (containing virus mRNAs) in independent experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Viral symptom observation also implied involvement or noninvolvement of dcl2 and agl, respectively, in the symptom alteration (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). In DK80 and the mutants lacking only agl (Δagl2, Δagl1/3/4, ΔaglQ, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2), RnVV1 and MyRV2 induced mild or no symptoms, respectively. RnVV1 and MyRV2 exhibited opposite symptom patterns in DK80. The RnVV1-induced symptoms were not obvious in the mutants lacking dcl2 (Δdcl2, Δdcl2Δagl2, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ), while the other mutants showed a slight reduction in aerial hyphae, implying the involvement of dcl2 in symptom induction by RnVV1. In contrast, MyRV2 reduced the growth rate in the mutants lacking dcl2, suggesting that dcl2 is involved in the mitigation of MyRV2-caused symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Viral symptoms in the dcl2/agl single and multiple knockout strains of C. parasitica. DK80 and its mutants infected by each virus or no virus (Fig. 3 A–E) were cultured on potato dextrose agar (5.5 cm in diameter) for 5 d after a small (1 mm3) mycelial plug was placed onto the center of each plate.

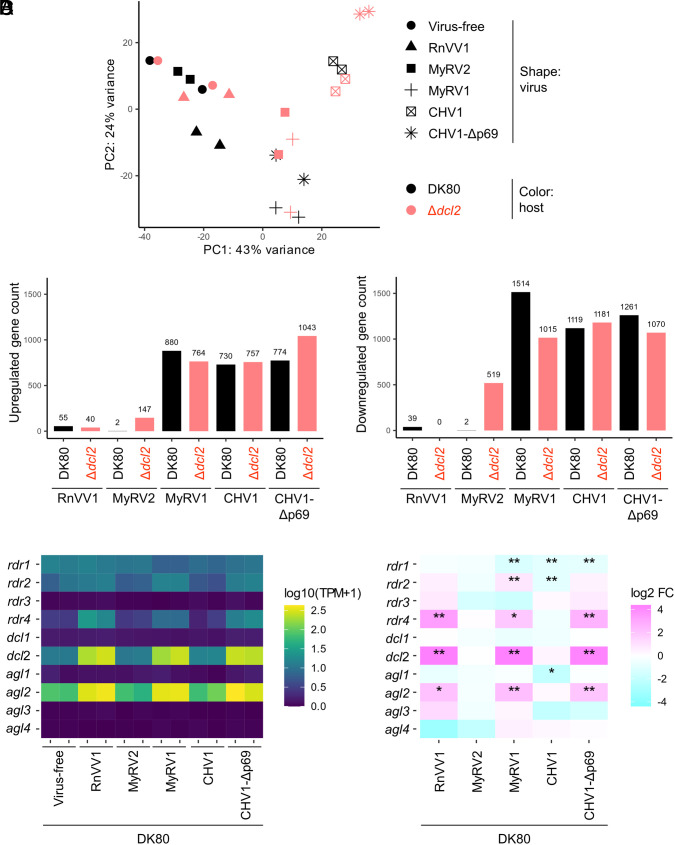

To examine viral impacts on transcriptome and the expression of RNAi genes, RNA-Seq analysis was performed in virus-free and virus-infected DK80 and Δdcl2. In the absence of virus, DK80 and Δdcl2 showed similar transcriptomic profiles (Fig. 5A). RnVV1-induced relatively small changes in the transcriptomes in DK80 and Δdcl2 (Fig. 5 A and B). MyRV2 induced little change in the transcriptome in DK80 but larger changes in the transcriptome of Δdcl2 (Fig. 5 A and B), consistently with the symptom severity (Fig. 4). In the absence of virus, the antiviral dcl and agl genes, namely dcl2 and agl2, were more expressed than the others, namely dcl1, agl1, agl3, and agl4, (Fig. 5C). In DK80, RnVV1 up-regulated dcl2 and agl2 as well as rdr4, but not the other RNAi-related genes (Fig. 5 C and D). The expression of any of the RNAi-related genes remained unaltered upon inoculation by MyRV2 (Fig. 5D), likely due to no or little accumulation of MyRV2 in the recipients (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7B).

Fig. 5.

Virus-induced transcriptomic changes in C. parasitica. The transcriptomes of C. parasitica strains DK80 and Δdcl2, which received each virus by hyphal fusion, were analyzed with virus-free strains as a control. There were two independent virus inoculations, representing two biological replicates of the transcriptomes. (A) Principle component (PC) analysis of the transcriptomes. (B) The count of upregulated genes [adjusted P value (padj) < 0.05, log2 fold change (log2 FC) > 0] or downregulated genes (padj < 0.05, log2 FC < 0) upon virus infection among a total of 11,609 genes. (C) The heat map of the expression level of RNAi-related genes, namely rdr (encoding host RDR polymerase), dcl, and agl (SI Appendix, Table S4). The expression level is shown as transcripts per million (TPM) plus one converted to the log10 scale. (D) The heat map of log2 FC of the RNAi-related genes induced by each virus. *P value < 0.05 but padj ≥ 0.05. **padj < 0.05.

These results collectively indicate that C. parasitica dcl2 predominantly contributes to RnVV1 and MyRV2 reduction and likely host symptom alteration, but no agl genes contribute to it, even redundantly.

Different agl2 Requirement Patterns for Antiviral Responses against the Other Viruses.

To compare with RnVV1 and MyRV2, we also tested the antiviral ability of the same C. parasitica mutants against MyRV1 (a close relative to MyRV2), CHV1 (a model ssRNA mycovirus), and CHV1-Δp69 (a mutant of CHV1 lacking an RSS p29) (Fig. 3 C–G). MyRV1 and CHV1 were highly accumulated in the RNAi-competent DK80 based on EtBr staining of the agarose gel (Fig. 3 C–E)—considering the band intensity of the genomic dsRNA (multisegmented MyRV1) or replicative form dsRNA of the genomic and defective (D1 and D2) (CHV1)—unlike RnVV1 and MyRV2 (Fig. 3 A and B). The difference in the accumulation level of MyRV1 among DK80 and the mutants was smaller, compared to the dramatic difference of RnVV1 and MyRV2 accumulation in the presence or absence of dcl2 (Fig. 3 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). Full-length CHV1 and CHV1-Δp69 replicative form dsRNA accumulated more in the mutants lacking dcl2 and/or agl2 compared with DK80 and Δagl1/3/4 (Fig. 3 D and E and SI Appendix, Figs. S6A and S7A). Defective interfering (DI) RNAs, which are produced spontaneously via internal deletion, are associated with CHV1 infection. We observed two types of DI RNAs (D1 and D2) in this study that were DCL2-dependent and -independent, respectively. The dcl2-dependent CHV1 DI RNA (39) was increased in DK80 and Δagl1/3/4 to a comparable level (“D1” in Fig. 3D), suggesting no contribution of agl1, agl3, and agl4 to the production of this defective RNA. CHV1 accumulated additional defective RNA in the mutants lacking dcl2 and/or agl2, but not in DK80 and Δagl1/3/4 (“D2” in Fig. 3D). DCL2 appeared to contribute to lower CHV1-Δp69 in the absence AGL2 (Fig. 3E). A similar trend was observed by qRT-PCR assay (SI Appendix, Figs. S6A and S7A). These results imply that full-scale anti-CHV1-Δp69 requires both AGL2 and DCL2, and DCL2 alone functions to reduce replicative dsRNA of CHV1-Δp69 to some extent. Upon infection by MyRV1 and CHV1-Δp69, DK80 and Δagl1/3/4 induced the expression of dcl2 and agl2 (Fig. 3 F and G). These data suggest no contribution of agl1, agl3, or agl4 to the regulation of dcl2 and agl2, where SAGA and DCL2 play key roles (25, 26).

In DK80, MyRV1, CHV1, and CHV1-Δp69 induced strong symptoms which were unaltered in Δagl1/3/4, suggesting agl1, agl3, or agl4 have no effect on viral symptom expression (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). CHV1 and CHV1-Δp69 severely reduced colony growth in the mutants lacking dcl2 and/or agl2 (Δdcl2, Δagl2, Δdcl2Δagl2, ΔaglQ, Δdcl2ΔaglQ, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2), suggesting contribution of both dcl2 and agl2 to symptom mitigation. MyRV1 induced slightly differential symptoms in the mutants lacking dcl2 compared with DK80 and the other mutants, as observed previously in EP155 Δdcl2 (23), suggesting contribution of dcl2 to the symptom alteration.

The virus-induced transcriptomic change was bigger in DK80 and Δdcl2 inoculated with MyRV1, CHV1, and CHV1-Δp69 compared with those inoculated with RnVV1 and MyRV2 (Fig. 5 A and B), consistent with the higher level of viral accumulation and symptom induction (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). The degree of change in transcriptomic profiles between DK80 and Δdcl2 differs depending on viruses (Fig. 5A), while the number of genes differentially expressed by MyRV1, CHV1, and CHV1-Δp69 was comparable between DK80 and Δdcl2 (Fig. 5B). Inoculation of MyRV1 and CHV1-Δp69 as well as RnVV1 up-regulated dcl2, agl2, and as well as rdr4, but not the other RNAi-related genes (Fig. 5 C and D). Inoculation of CHV1 did not significantly change the expression of any of the RNAi-related genes (Fig. 5 C and D), which could be explained by the function of its p29 RSS (21, 25, 27).

Taken together, these results suggest that 1) C. parasitica agl1, agl3, and agl4 are neither induced by the tested viruses nor involved in antiviral function against MyRV1, CHV1, and CHV1-Δp69; 2) agl2 shows antiviral effects against the viruses relatively highly accumulated in the RNAi-competent DK80; 3) dcl2 contributes to viral reduction in both the presence and absence of an RSS p29 in CHV1 (CHV1-Δp69).

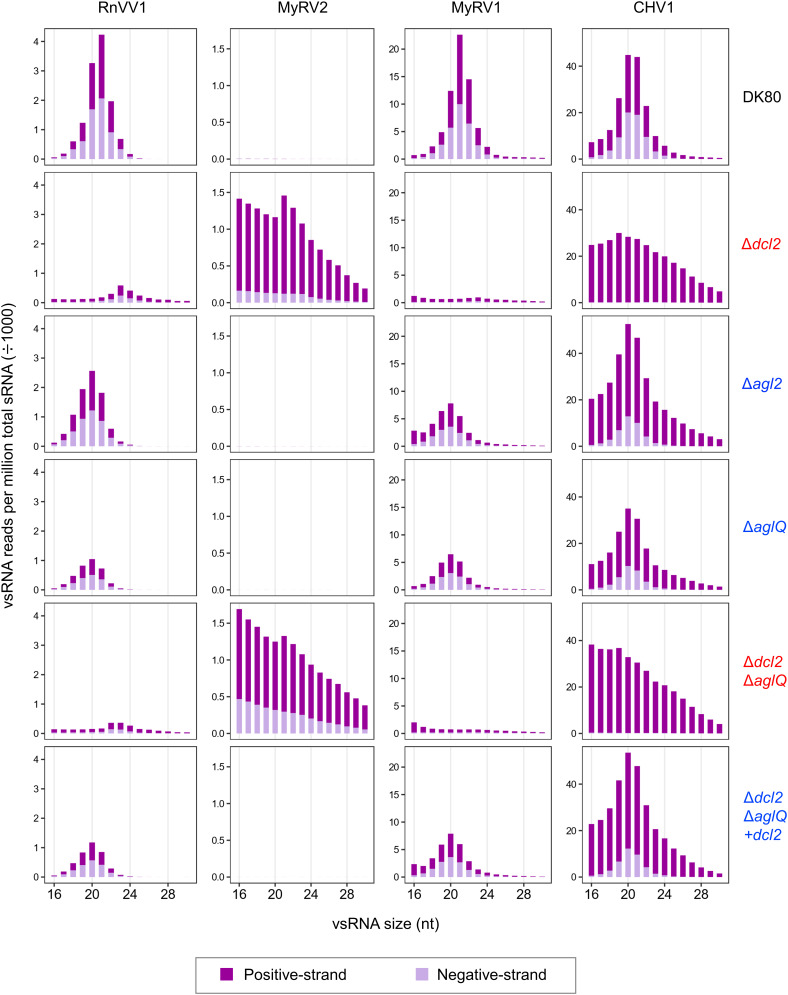

Small RNA Analysis Provides Insights into the Dicer-Alone Anti-RnVV1 Defense.

We were interested in virus-derived small RNA (vsRNA) accumulation in the presence or absence of agl genes in C. parasitica, where the DCL2-dependent antiviral defense operated. To this end, we analyzed vsRNA profiles in DK80, Δdcl2, Δagl2, ΔaglQ, Δdcl2ΔaglQ, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2, infected by each of RnVV1, MyRV2, MyRV1, and CHV1. In DK80, vsRNAs of RnVV1, MyRV1, and CHV1 peaked at 20 or 21 nucleotides (nt) for either strand, while vsRNAs of MyRV2 were hardly detected (Fig. 6). In the mutants lacking agl genes but carrying dcl2 gene (Δagl2, ΔaglQ, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2), vsRNAs of RnVV1, MyRV1, and CHV1 retained a peak at 20 or 21 nt with changes in relative vsRNA abundance compared to those in DK80, while vsRNAs of MyRV2 were still hardly detected (Fig. 6). The poor detection of vsRNA reads of MyRV2 in the dcl2-carrying fungal strains is likely due to no or little accumulation of MyRV2 which is highly susceptible to the DCL2-dependent defense (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7B). Surprisingly, even in the absence of Δdcl2, positive- and negative-strand vsRNAs derived from RnVV1 clearly peaked at 23 nt (Δdcl2) or 22 to 23 nt (Δdcl2ΔaglQ), a shift from the peak at 20 to 21 nt for DK80, Δagl2, ΔaglQ, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2 (Fig. 6). This size class of small RNAs may have been generated in a Dicer-independent way, as occurs in a filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa (40), or by DCL1. As reported earlier for the C. parasitica EP155 strain (25), the absence of dcl2 (Δdcl2, Δdcl2ΔaglQ) resulted in high accumulation of vsRNAs corresponding to the positive-strand of CHV1—with a lack of sharp peaks at 20 or 21 nt—with no or little negative-strand vsRNAs (Fig. 6). The mutants lacking dcl2 (Δdcl2, Δdcl2ΔaglQ) infected by MyRV2 and MyRV1 also showed a similar accumulation pattern of vsRNAs predominantly from the positive-strand without a clear peak at the typical vsRNA size (Fig. 6). The relative number of MyRV2 vsRNA reads are higher in these mutants lacking dcl2 compared to those in the other fungal strains (Fig. 6), which was correlated with the MyRV2 accumulation level (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7B).

Fig. 6.

Accumulation of vsRNA in the dcl2/agl single and multiple knockout strains of C. parasitica. The x-axis shows size distributions (16 to 30 nt) of RnVV1-, MyRV2-, MyRV1-, or CHV1-derived vsRNAs. The y-axis shows normalized vsRNA read counts [reads per million (RPM) divided by 1,000, normalized to total small RNAs in C. parasitica strain DK80 or its derivative mutants (Δdcl2, Δagl2, ΔaglQ, Δdcl2ΔaglQ, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2) infected by each virus].

Taken together, these findings suggest that RnVV1 vsRNAs with a peak of 20 or 21 nt functions as virus-derived siRNA (vsiRNA) in the C. parasitica Dicer-alone defense in the absence of AGLs (Δagl2, ΔaglQ, Δdcl2ΔaglQ+dcl2), while RnVV1-derived sRNAs with a peak of 22 and/or 23 nt produced in dcl2-lacking mutants (Δdcl2, Δdcl2ΔaglQ) appears to be dysfunctional in the antiviral defense.

Discussion

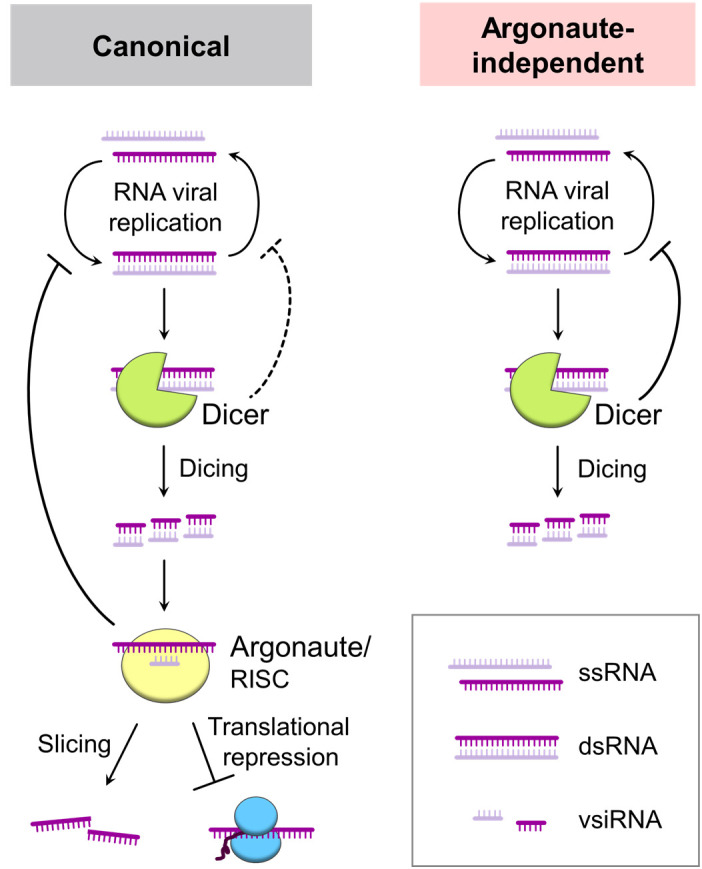

This study revealed two-step antiviral RNAi in C. parasitica: Argonaute-independent, Dicer-mediated defense and full-scale RNAi requiring both Argonaute and Dicer (Fig. 7). Two dsRNA viruses, RnVV1 (a victorivirus) and MyRV2 (a mycoreovirus), were susceptible to the Dicer-alone defense, while CHV1 (a ssRNA hypovirus) and MyRV1 (a mycoreovirus) were not susceptible to it (Figs. 2 and 3). It is generally accepted that Dicer (DCL) is necessary but not sufficient and requires Argonaute (AGL) activity as the effector for antiviral RNAi (41). However, a Dicer-mediated, sequence-nonspecific antiviral defense has previously been discussed in plant systems (12), but it has not yet been demonstrated. The authors concluded that Argonaute is necessary in the end based on several pieces of evidence, such as the observation that agl1/agl2 double mutants are hypersusceptible to a plant ssRNA virus, cucumber mosaic virus (12, 42). As mentioned in the Introduction, it is technically difficult to fully address whether the Dicer-alone defense works for some other viruses in plants or other eukaryotes because they have a large number of Argonaute paralogs and the Argonaute-associated miRNA pathway is crucial for development. By contrast, deletion mutants of fungal RNAi genes, even quadruple null mutants of all agl genes (ΔaglQ), showed normal colony growth in the absence of virus (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4), which led to our findings in this study. This observation may suggest that agl genes in C. parasitica and possibly in other ascomycetes, do not play pivotal roles in vegetative growth and development unlike in other higher eukaryotes. In a model filamentous fungus, N. crassa, miRNA-like small RNAs (milRNAs) are produced by multiple pathways (40), and one (qde-2) of the two argonaute genes is involved in one of multiple milRNA biogenesis pathways (43). However, single or double mutants of the two N. crassa Argonaute genes (qde-2 and sms-2) show normal vegetative growth in the absence of virus infection (44).

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of Argonaute-independent antiviral silencing. In canonical antiviral silencing/RNAi (Left), Dicer (or DCL) dices viral dsRNA into vsiRNAs, and then Argonaute (or AGL) incorporates the vsiRNA to slice or translationally repress the target viral ssRNA. In this case, both Dicer and Argonaute could contribute to the inhibition of viral replication. In contrast, this study also suggests that infection of some viruses (RnVV1 and MyRV2) can be suppressed in an Argonaute-independent manner (Right), by dicing of viral replicative/genomic dsRNA to block the replication cycle of RNA viruses in the realm Riboviria.

What determines the level of susceptibility of different viruses to the Dicer-alone defense in fungi remains elusive. The interactions between host antiviral RNAi and viral counterattack, more concretely dcl2 expression levels and viral RSS activities, may partly account for this phenomenon, although we cannot rule out other factors. As mentioned above, RnVV1 and MyRV2 were susceptible enough to be restricted by the action of DCL2 alone (Fig. 3 A and B). As consistent with the previous observation in strain EP155 of C. parasitica (32), RnVV1 accumulated at a low level in DK80 in the presence of DCL2 (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). RnVV1 up-regulated dcl2 transcript levels (Fig. 5 C and D). MyRV2 is potentially able to induce dcl2 transcription as long as it can infect host fungi stably (45), while in DK80, MyRV2 cannot apparently establish stable infection (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7B). MyRV2 was isolated from a C. parasitica fungal strain coinfected by a hypovirus (CHV4-C18) with a positive-sense RNA genome that encodes an RSS homologous to CHV1 p29 (45, 46). MyRV2 probably needs the hypovirus for efficient suppression of antiviral RNAi and for stable maintenance in the host under natural conditions (46), suggesting that MyRV2 does not have a strong RSS. Similarly, RnVV1 appears to lack a strong CHV1 p29-like RSS that can cancel dcl2 induction, given that RnVV1-infection highly induces the dcl2 transcript level (Fig. 5 C and D). Therefore, the susceptibility of these viruses to the Dicer-alone defense appears to be equivalent to the pronounced effects of deletion of RNAi-related genes in RSS-lacking viruses of other host kingdoms of host organisms (8, 47).

The stark contrast between the two sister mycoreoviruses, MyRV1 and MyRV2, in susceptibility to the Dicer-alone defense is of great interest. This difference likely led to the distinct colony phenotypes (Fig. 4), vsRNA profiles (Fig. 6), and altered gene expression (Fig. 5) between C. parasitica mutant strains infected by the two mycoreoviruses. Namely, MyRV1 affected colony morphology of all fungal strains, while MyRV2 induced symptoms only in the dcl2-lacking mutants (Δdcl2, Δdcl2Δagl2, and Δdcl2ΔaglQ) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the number of differentially expressed genes including RNAi-related genes is much smaller in MyRV2-infected DK80 than in MyRV1-infected DK80 (Fig. 5). VsRNAs were produced much less in dcl2-competent fungal strains infected by MyRV2 than in those infected by MyRV1 (Fig. 6). No Dicer-alone defense against MyRV1 was discernable regardless of the presence or absence of agl2 (Fig. 3C), suggesting its tolerance to antiviral RNAi, despite the high dcl2 induction (Figs. 3F and 5D). The genus Mycoreovirus accommodates another member R. necatrix mycoreovirus 3 (MyRV3) as well as the above two mycoreoviruses (48). One of the MyRV3-encoded proteins, VP10, was identified as an RSS (49), but no homologous protein is detected in MyRV1 or MyRV2. Future comparative functional analyses of the genomic segments homologous between MyRV1 and MyRV2 will provide some clues.

This study provides insights into the functional roles of Argonaute family members. Fungal Argonaute homologs (AGL) are largely divided into two groups, the so-called quelling and meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA (MSUD) clades, based on the phylogenetic affinity to the two Argonaute proteins, QDE2 (quelling-defective 2) and SMS2 (suppressor of meiotic silencing-2), of the model filamentous fungus N. crassa (50). In N. crassa, QDE2 and SMS2 work in the vegetative and sexual stages, respectively (51, 52), and QDE2, but not SMS2, contributes to viral RNA reduction in the vegetative growth condition (44). Similarly to QDE2, all antiviral Argonaute proteins from various filamentous fungi belong to the same quelling clade, as exemplified by AGL2 in C. parasitica (53). There are a few exceptions to this with phytopathogenic fungi, including FgAGO2 (a MSUD clade member) from Fusarium graminearum (53, 54). Both FgAGO1 (a quelling clade member) and FgAGO2, whose genes are induced upon virus infection, play antiviral roles (54). The second example is from Magnaporthe oryzae that carries three Argonaute paralogs. MoAGO2 and MoAGO3, which belong to the quelling clade, exert contrasting effects: MoAGO3 contributes to viral RNA reduction, whereas MoAGO2 functions as a proviral factor likely by competing with antiviral MoAGO3 over vsiRNA binding (55). Other functional roles of MoAGO2 remain unknown. Much simpler antiviral RNAi appears to operate in C. parasitica, in which only DCL2 and AGL2 are functional (10, 21, 23). Their genes (dcl2 and agl2) are upregulated upon virus infection at the vegetative stage on medium to a much higher extent than dcl1, agl1, agl3, and agl4, which were not induced by the tested viruses (Fig. 5 C and D). It should be noted that agl1, agl3, and agl4 are up-regulated in sexual fruiting bodies of C. parasitica on its natural host plant (chestnut) (21), so the antiviral contribution of these agl genes in untested conditions (e.g., at sexual stage) remains to be determined. The antiviral roles of C. parasitica dcl2 and agl2 in the tested conditions appear to require their appropriate temporal and spatial expression.

Eukaryotic antiviral RNAi has been proposed to have evolved from the prokaryotic/archaeal Argonaute-mediated antiviral mechanism, in which Dicer is not involved (1, 56), implying that Argonaute precedes Dicer on an evolutionary time scale. Dicer is hypothesized to have evolved by fusion of prokaryotic RNase III and archaeal helicase (57). RNase III family proteins are structurally classified into three classes, where Dicer belongs to class III (58). Besides Dicer, Drosha, a class II type of RNase III family protein, also plays a role in miRNA processing (59) and serves as a direct antiviral effector, independent of miRNA (60). Conceptionally, the second role somewhat resembles the direct antiviral effect of Dicer observed in this study. However, Drosha exerts its antiviral activity by binding to viral RNA and inhibiting viral RNA synthesis through viral RdRP (60), while the antiviral effect of Dicer identified in this study is likely attributed to its dicing of viral-derived dsRNA based on the vsiRNA production (Fig. 6). In this regard, the Dicer-alone antiviral defense is more similar to the antiviral defense mediated by the 5′→3′ cytoplasmic exoribonuclease, which was first observed in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (61–63) and later in various eukaryotes such as mammals (64) and plants (65). The Dicer-alone antiviral RNA defense we identified in this study resembles these defense mechanisms in that the effector molecules have nuclease activities in a sequence-nonspecific manner. The Argonaute-independent, Dicer-dependent antiviral defense may require high levels of Dicer accumulation induced by virus infection or dsRNA expression (21, 23, 66), which may be functionally equivalent to the RdRP-mediated siRNA amplification circuit in plants (22).

Materials and Methods

The viral and fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 and SI Appendix, Table S3. The fungal strains were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (BD Difco) on laboratory shelves at room temperature in natural daylight. Disruptants of C. parasitica RNAi genes were basically prepared via HR-mediated gene replacement, and validated by genomic PCR and Southern blotting (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3). Virus inoculation was conducted by conventional virion transfection or coculturing of donor and recipient fungal strains (25, 32). RNA isolation and subsequent analyses were performed as described earlier (25, 32). All detailed protocols and materials are described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. Any materials or related protocols mentioned in this work can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Yomogi Inc. (to N.S.), and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) and on Innovative Areas, and Grants-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) (KAKENHI 21H05035, 21K18222, 16H06436, 16H06429, and 16K21723 to N.S. and H.K., and 19J00261 to Y.S.). The fungal strains 9B21/MyRV1, C18/MyRV2, EP155, EP155/CHV1, and EP155/CHV1-Δp69 were generous gifts from Drs. Donald L. Nuss and Bradley I. Hillman. The fungal strain DK80 was generously provided by Dr. Bao-shan Chen (Guangxi University, China). The plasmid vectors pKAES175, pAL12-Lifeact, or pCB1636_lox_HPT-TK were generously provided by Dr. Christopher L. Schardl (University of Kentucky), Dr. Shinji Honda (University of Fukui, Japan), or Dr. Koji Yamada (Tokushima University, Japan), respectively. We are grateful to Ms. Sakae Hisano and Dr. Annisa Aulia for their excellent technical support for qRT-PCR and preparation of the fungal strains (EP155Δdcl2/MyRV2 and EP155/CHV4), respectively.

Author contributions

Y.S. and N.S. designed research; Y.S. performed research; Y.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Y.S., H.K., and N.S. analyzed data; and Y.S., H.K., and N.S. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The genome sequence and gene annotation of C. parasitica is available in genome portal C. parasitica EP155 v2.0 (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/Crypa2) organized by Joint Genome Institute (36). Gene and viral sequences are available under the accession numbers listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. All other data are available in the manuscript and SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.tenOever B. R., The evolution of antiviral defense systems. Cell Host Microbe 19, 142–149 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aliyari R., Ding S. W., RNA-based viral immunity initiated by the Dicer family of host immune receptors. Immunol. Rev. 227, 176–188 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baulcombe D. C., The role of viruses in identifying and analyzing RNA silencing. Annu. Rev. Virol. 9, 353–373 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuss D. L., Mycoviruses, RNA silencing, and viral RNA recombination. Adv. Virus. Res. 80, 25–48 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Z., Li Y., Ding S. W., Small RNA-based antimicrobial immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 31–44 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghildiyal M., Zamore P. D., Small silencing RNAs: An expanding universe. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 94–108 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voinnet O., Use, tolerance and avoidance of amplified RNA silencing by plants. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 317–328 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X. H., et al. , RNA interference directs innate immunity against viruses in adult Drosophila. Science 312, 452–454 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Ruiz H., et al. , Arabidopsis RNA-dependent RNA polymerases and dicer-like proteins in antiviral defense and small interfering RNA biogenesis during Turnip Mosaic Virus infection. Plant Cell 22, 481–496 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segers G. C., Zhang X., Deng F., Sun Q., Nuss D. L., Evidence that RNA silencing functions as an antiviral defense mechanism in fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12902–12906 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mourrain P., et al. , Arabidopsis SGS2 and SGS3 genes are required for posttranscriptional gene silencing and natural virus resistance. Cell 101, 533–542 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pumplin N., Voinnet O., RNA silencing suppression by plant pathogens: Defence, counter-defence and counter-counter-defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 745–760 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang X., Qi Y., RNAi in plants: An Argonaute-centered view. Plant Cell 28, 272–285 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wienholds E., Plasterk R. H., MicroRNA function in animal development. FEBS Lett. 579, 5911–5922 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morel J. B., et al. , Fertile hypomorphic ARGONAUTE (ago1) mutants impaired in post-transcriptional gene silencing and virus resistance. Plant Cell 14, 629–639 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki T., Shiohama A., Minoshima S., Shimizu N., Identification of eight members of the Argonaute family in the human genome. Genomics 82, 323–330 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams R. W., Rubin G. M., ARGONAUTE1 is required for efficient RNA interference in Drosophila embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6889–6894 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yigit E., et al. , Analysis of the C. elegans argonaute family reveals that distinct argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell 127, 747–757 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigling D., Prospero S., Cryphonectria parasitica, the causal agent of chestnut blight: Invasion history, population biology and disease control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 7–20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eusebio-Cope A., et al. , The chestnut blight fungus for studies on virus/host and virus/virus interactions: From a natural to a model host. Virology 477, 164–175 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Q., Choi G. H., Nuss D. L., A single Argonaute gene is required for induction of RNA silencing antiviral defense and promotes viral RNA recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17927–17932 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D. X., Spiering M. J., Nuss D. L., Characterizing the roles of Cryphonectria parasitica RNA-dependent RNA polymerase-like genes in antiviral defense, viral recombination and transposon transcript accumulation. PLoS One 9, e108653 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiba S., Suzuki N., Highly activated RNA silencing via strong induction of dicer by one virus can interfere with the replication of an unrelated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4911–E4918 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aulia A., Tabara M., Telengech P., Fukuhara T., Suzuki N., Dicer monitoring in a model filamentous fungus host, Cryphonectria parasitica. Curr. Res. Virol. Sci. 1, 100001 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andika I. B., Kondo H., Suzuki N., Dicer functions transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally in a multilayer antiviral defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 2274–2281 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andika I. B., Jamal A., Kondo H., Suzuki N., SAGA complex mediates the transcriptional up-regulation of antiviral RNA silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E3499–E3506 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X., Segers G. C., Sun Q., Deng F., Nuss D. L., Characterization of hypovirus-derived small RNAs generated in the chestnut blight fungus by an inducible DCL-2-dependent pathway. J. Virol. 82, 2613–2619 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swarts D. C., et al. , The evolutionary journey of Argonaute proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 743–753 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan X., et al. , Deletion of the cpku80 gene in the chestnut blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, enhances gene disruption efficiency. Curr. Genet. 53, 59–66 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang D. X., Lu H. L., Liao X., St Leger R. J., Nuss D. L., Simple and efficient recycling of fungal selectable marker genes with the Cre-loxP recombination system via anastomosis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 61, 1–8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapira R., Choi G. H., Nuss D. L., Virus-like genetic organization and expression strategy for a double-stranded RNA genetic element associated with biological control of chestnut blight. EMBO J. 10, 731–739 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiba S., Lin Y. H., Kondo H., Kanematsu S., Suzuki N., A novel victorivirus from a phytopathogenic fungus, Rosellinia necatrix is infectious as particles and targeted by RNA silencing. J. Virol. 87, 6727–6738 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki N., Supyani S., Maruyama K., Hillman B. I., Complete genome sequence of Mycoreovirus-1/Cp9B21, a member of a novel genus within the family Reoviridae, isolated from the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 3437–3448 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enebak S. A., Macdonald W. L., Hillman B. I., Effect of dsRNA associated with Isolates of Cryphonectria parasitica from the central Appalachians and their relatedness to other dsRNA from North America and Europe. Phytopathology 84, 528–534 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki N., Nuss D. L., Contribution of protein p40 to hypovirus-mediated modulation of fungal host phenotype and viral RNA accumulation. J. Virol. 76, 7747–7759 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crouch J. A., et al. , Genome sequence of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica EP155: A fundamental resource for an archetypical invasive plant pathogen. Phytopathology 110, 1180–1188 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun L., Nuss D. L., Suzuki N., Synergism between a mycoreovirus and a hypovirus mediated by the papain-like protease p29 of the prototypic hypovirus CHV1-EP713. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 3703–3714 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eusebio-Cope A., Suzuki N., Mycoreovirus genome rearrangements associated with RNA silencing deficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3802–3813 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X., Nuss D. L., A host dicer is required for defective viral RNA production and recombinant virus vector RNA instability for a positive sense RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16749–16754 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee H. C., et al. , Diverse pathways generate microRNA-like RNAs and Dicer-independent small interfering RNAs in fungi. Mol. Cell 38, 803–814 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva-Martins G., Bolaji A., Moffett P., What does it take to be antiviral? An Argonaute-centered perspective on plant antiviral defense. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 6197–6210 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X. B., et al. , The 21-nucleotide, but not 22-nucleotide, viral secondary small interfering RNAs direct potent antiviral defense by two cooperative argonautes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 23, 1625–1638 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue Z., Yuan H., Guo J., Liu Y., Reconstitution of an Argonaute-dependent small RNA biogenesis pathway reveals a handover mechanism involving the RNA exosome and the exonuclease QIP. Mol. Cell 46, 299–310 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Honda S., et al. , Establishment of Neurospora crassa as a model organism for fungal virology. Nat. Commun. 11, 5627 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aulia A., Andika I. B., Kondo H., Hillman B. I., Suzuki N., A symptomless hypovirus, CHV4, facilitates stable infection of the chestnut blight fungus by a coinfecting reovirus likely through suppression of antiviral RNA silencing. Virology 533, 99–107 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aulia A., et al. , Identification of an RNA silencing suppressor encoded by a symptomless fungal hypovirus, Cryphonectria hypovirus 4. Biology (Basel) 10, 100 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aliyari R., et al. , Mechanism of induction and suppression of antiviral immunity directed by virus-derived small RNAs in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe 4, 387–397 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matthijnssens J., et al. , ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Spinareoviridae 2022. J. Gen. Virol. 103, 001781 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaegashi H., Yoshikawa N., Ito T., Kanematsu S., A mycoreovirus suppresses RNA silencing in the white root rot fungus, Rosellinia necatrix. Virology 444, 409–416 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campo S., Gilbert K. B., Carrington J. C., Small RNA-based antiviral defense in the phytopathogenic fungus Colletotrichum higginsianum. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005640 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cogoni C., Macino G., Isolation of quelling-defective (qde) mutants impaired in posttranscriptional transgene-induced gene silencing in Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10233–10238 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee D. W., Pratt R. J., McLaughlin M., Aramayo R., An argonaute-like protein is required for meiotic silencing. Genetics 164, 821–828 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sato Y., Suzuki N., Continued mycovirus discovery expanding our understanding of virus lifestyles, symptom expression, and host defense. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 75, 102337 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu J., Lee K. M., Cho W. K., Park J. Y., Kim K. H., Differential contribution of RNA interference components in response to distinct Fusarium graminearum virus infections. J. Virol. 92, e01756-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen Q., et al. , A fungal Argonaute interferes with RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 2495–2508 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koonin E. V., Evolution of RNA- and DNA-guided antivirus defense systems in prokaryotes and eukaryotes: Common ancestry vs convergence. Biol. Direct. 12, 5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shabalina S. A., Koonin E. V., Origins and evolution of eukaryotic RNA interference. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 578–587 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carmell M. A., Hannon G. J., RNase III enzymes and the initiation of gene silencing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 214–218 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han J., et al. , The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 18, 3016–3027 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aguado L. C., et al. , RNase III nucleases from diverse kingdoms serve as antiviral effectors. Nature 547, 114–117 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toh-e A., Guerry P., Wickner R. B., Chromosomal superkiller mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 136, 1002–1007 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Esteban R., Vega L., Fujimura T., 20S RNA narnavirus defies the antiviral activity of SKI1/XRN1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25812–25820 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wickner R. B., Viruses and prions of yeasts, fungi, and unicellular organisms in “Fields Virology”, 7th Edition, Knipe D. M., Howley P. M., Eds. (Wolster Kluwer, Philadelphia, ed. 7, 2023), vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y., Masaki T., Yamane D., McGivern D. R., Lemon S. M., Competing and noncompeting activities of miR-122 and the 5’ exonuclease Xrn1 in regulation of hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1881–1886 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li F. F., Wang A. M., RNA decay is an antiviral defense in plants that is counteracted by viral RNA silencing suppressors. PloS Pathog. 14, e1007228 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choudhary S., et al. , A double-stranded-RNA response program important for RNA interference efficiency. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 3995–4005 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequence and gene annotation of C. parasitica is available in genome portal C. parasitica EP155 v2.0 (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/Crypa2) organized by Joint Genome Institute (36). Gene and viral sequences are available under the accession numbers listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. All other data are available in the manuscript and SI Appendix.