Injury accounts for almost 40% of annual deaths in children aged 1 to 14 in the world's most developed nations, says a new report by Unicef released this week.

Traffic accidents, intentional injuries, drowning, falls, fires, poisonings, and other hazards kill more than 20000 children aged under 15 every year. This makes preventable injuries the principal cause of child death in developed nations.

Peter Adamson, one of the report's authors, said: “Over 500 children, anonymous to most of us, died from accidents this year [in the United Kingdom], but their families are just as bereaved as those of high profile murder cases.” Deaths from traffic accidents account for 41% of all child deaths by injury, and boys are 70% more likely to die by injury than girls.

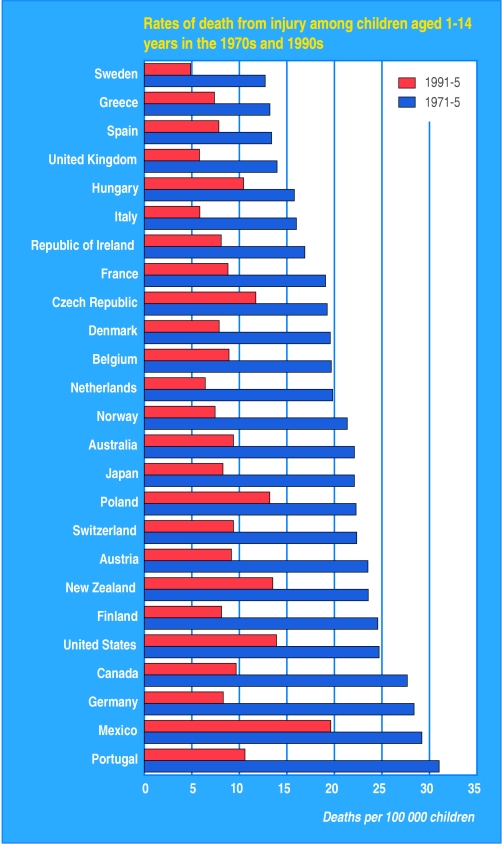

The report presents a standardised league table of child injury deaths per 100000 children between 1991 and 1995 for nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), using mortality data from the World Health Organization.

Sweden and the United Kingdom have the best records on child safety, occupying the top two places of the 26 country league table, with Sweden having just over five child injury deaths per 100000 children. The bottom two places are occupied by Mexico and South Korea, with rates three to four times higher than the leading countries. The United States and Portugal have rates twice as high as the leading countries.

Unicef estimates that at least 2000 deaths a year could be prevented if all OECD countries had the same child injury death rate as Sweden. Dr Elizabeth Towner, a contributor to the report, warned: “We need more research to see what effect decreased deaths has had on disability.”

The number of child deaths by injury in OECD nations fell by about 50% between 1970 and 1995. In 16 cases countries more than halved their child injury death rates over this period. Peter Adamson said: “It is very evident that the [OECD] countries have been progressing at very different speeds.” He emphasised that “steep reductions are not the result of a magic wand, but of policy.”

Despite good overall performance, the United Kingdom has shown a clear disparity between the rich and poor sections of the population.

Innocenti Report Card No 2: A League Table of Child Deaths by Injury in Rich Nations is available at www.unicef.org.uk

Figure.

Child deaths from injuries halved between 1970 and 1995, but some countries moved faster than others. Australia and New Zealand, for example, started with similar rates, but by the mid-1990s Australia had cut its rate by 60% while New Zealand's fell by only 40%