A man who had sex with his girlfriend without telling her that he was infected with HIV is facing the prospect of a long prison term after being convicted of culpable and reckless behaviour in the first case of its kind in Britain.

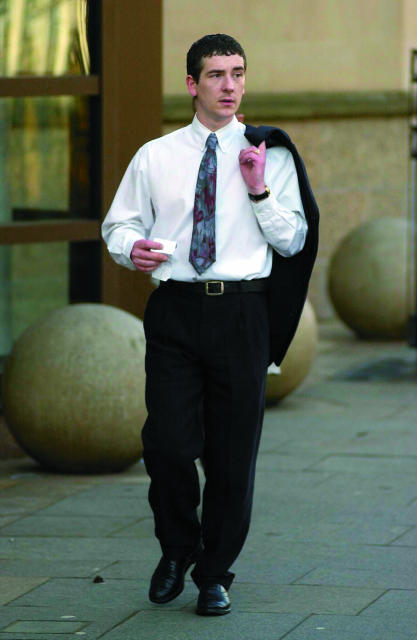

As the BMJ went to press, Stephen Kelly, aged 33, was awaiting sentence at the High Court in Glasgow on 16 March after the first trial in a British court of someone recklessly passing on the virus through sex.

The prosecution has alarmed research scientists because the scientific evidence that secured Mr Kelly's conviction came from confidential data that were obtained by a police warrant. Mr Kelly had agreed to give a sample as part of a molecular investigation into an outbreak of HIV through needle sharing at Glenochil prison in Glasgow, where he was serving a sentence at the time.

The results of that study were published in the BMJ in 1997. The police learned that Mr Kelly was one of the prisoners who had become infected as part of the outbreak. They then discovered that a sample taken from his former girlfriend, Anne Craig, had been forwarded by her clinician to a research project on the molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), and that the researchers had linked her virus with the Glenochil virus.

Andrew Leigh Brown, professor of evolutionary genetics and head of the Centre for HIV Research at Edinburgh University, who was responsible for the northern part of the MRC study, had asked clinicians to notify him of any newly infected cases.

“The clinician contributed that sample of a sexual transmission case and told us it was linked to the Glenochil cluster. We could say this transmission was of a virus very similar to the Glenochil cluster and distinct from other viruses that we see in Scotland.

“The thing that concerned me was that these samples were presented as part of a bona fide research programme and in confidence, and I was frankly appalled when this information was pulled out as part of this investigation, and there seemed to be nothing I could do about it,” he said. “Lawyer friends said with a warrant as broad as that in a criminal case they can take whatever they want.

As far as my own research is concerned, I wouldn't touch another molecular epidemiology investigation in Scotland unless there is some clarification of whether this seizure of material is or is not appropriate. It was not raised as an issue in the case whether this material was obtained in an appropriate way. We by chance occasionally identify individuals who have linked viruses and this would open them to a whole series of processes.

A number of prisoners refused to be tested. Those who were tested were counselled and told the samples were going to be contributed anonymously. There are whole areas of contact tracing and so on which are thrown up by this.”

Professor Leigh Brown, who was an expert witness in the case, is currently a visiting professor in the pathology department of the University of California in San Diego. He added: “To me it seems this was an invasion of human rights. Talking to individuals here in California, they are appalled. They say this would not happen in California; it is expressly forbidden by American regulations relating to privacy.”

Figure.

SPINDRIFT

Stephen Kelly gave a sample as part of a research project