Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations accelerate loss of lung function and increased mortality. The complex nature of COPD presents challenges in accurately predicting and understanding frequent exacerbations. The present study aimed to assess the metabolic characteristics of the frequent exacerbation of COPD (COPD-FE) phenotype, identify potential metabolic biomarkers associated with COPD-FE risk and evaluate the underlying pathogenic mechanisms. An internal cohort of 30 stable patients with COPD was recruited. A widely targeted metabolomics approach was used to detect and compare serum metabolite expression profiles between patients with COPD-FE and patients with non-frequent exacerbation of COPD (COPD-NE). Bioinformatics analysis was used for pathway enrichment analysis of the identified metabolites. Spearman's correlation analysis assessed the associations between metabolites and clinical indicators, while receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis evaluated the ability of metabolites to distinguish between two groups. An external cohort of 20 patients with COPD validated findings from the internal cohort. Out of the 484 detected metabolites, 25 exhibited significant differences between COPD-FE and COPD-NE. Metabolomic analysis revealed differences in lipid, energy, amino acid and immunity pathways. Spearman's correlation analysis demonstrated associations between metabolites and clinical indicators of acute exacerbation risk. ROC analysis demonstrated that the area under the curve (AUC) values for D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (AUC=0.871), arginine (AUC=0.836), L-2-hydroxyglutarate (L-2HG; AUC=0.849), diacylglycerol (DG) (16:0/20:5) (AUC=0.827), DG (16:0/20:4) (AUC=0.818) and carnitine-C18:2 (AUC=0.804) were >0.8, highlighting their discriminative capacity between the two groups. External validation results demonstrated that DG (16:0/20:5), DG (16:0/20:4), carnitine-C18:2 and L-2HG were significantly different between patients with COPD-FE and those with COPD-NE. In conclusion, the present study offers insights into early identification, mechanistic understanding and personalized management of the COPD-FE phenotype.

Keywords: COPD, metabolomics, metabolites, ‘frequent exacerbator’ phenotype, biomarkers

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent, preventable and treatable chronic inflammatory airway disease, and is the third leading cause of mortality worldwide (1). The frequent exacerbation of COPD (COPD-FE) phenotype is characterized by experiencing two or more exacerbation episodes annually (2). Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) are critical events that accelerate lung function decline, elevate mortality (3,4) and adversely affect mental health (MH) and quality of life in patients with COPD (5,6). Therefore, the central focus of COPD management during stable periods revolves around averting acute exacerbations and reducing their frequency.

Numerous clinical predictors of acute exacerbation risk in COPD have been assessed, including low body mass index (BMI) (7), deteriorating lung function (8), increased COPD assessment test (CAT) scores (9), modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale scores (10), and elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) (11). However, predicting COPD-FE risk and understanding its underlying pathogenic mechanisms remains challenging due to the heterogeneity and complexity of COPD. Moreover, effective preventive measures against COPD-FE remain unsatisfactory. Therefore, a multidimensional exploration of intrinsic COPD-FE mechanisms and the identification of predictive biomarkers is essential for enhancing comprehensive COPD management during stable periods.

Widely targeted metabolomics, a high-throughput bioanalytical technique, is designed to identify and quantify small-molecule metabolites within biological specimens (12). This method integrates the benefits of both non-targeted and targeted metabolite detection, offering a high-throughput, specific, sensitive and accurate approach (13). It enables the simultaneous analysis of hundreds to thousands of metabolites. It has broad applications across diverse medical fields, such as drug screening, research on metabolic diseases and exploring metabolic networks within living organisms (14). Although recent studies have begun to identify the metabolic characteristics in blood samples of individuals with different COPD phenotypes, these studies often rely on non-targeted metabolomics or are confined to specific metabolic pathways (15–18). Moreover, research using widely targeted metabolomics for the COPD-FE phenotype is currently insufficient.

In the present study, a widely targeted metabolomics approach based on ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) was used for what is considered to be the first time, coupled with multivariate and univariate statistical analyses, to assess the serum metabolic profile and potential pathway changes in patients with a COPD-FE phenotype. Furthermore, through Spearman's correlation analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the predictive capacity of differential metabolites for assessing the risk of COPD-FE were evaluated. Finally, external cohort validation was performed to further determine the reliability of the results of the present study.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was conducted following The Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Hefei, China; approval no. 2021AH-31). The present study is an observational study and, during its course, no new interventions were introduced. All participants provided written informed consent. The present study constitutes a subset of patients with COPD recruited from a larger unpublished cohort study conducted by the present research group. Patients with COPD who had previously received treatment at The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine were screened. Between April and June 2022, 80 patients with COPD underwent preliminary screening and exclusion, leading to the successful recruitment of 50 participants (30 for internal validation and 20 for external validation).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Fulfilled diagnostic criteria for COPD; ii) patients were in a stable phase of COPD, with no acute exacerbations for ≥4 weeks before enrolment (1); iii) age range of 60–80 years; iv) had not participated in any other clinical studies within the preceding 3 months; and v) adhered to a light diet and regular lifestyle for ≥6 weeks before enrolment. The diagnosis of COPD was based on the 2020 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, defining COPD as a post-bronchodilator ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) FEV1/FVC ratio of <70% (1). The exclusion criteria included adverse habits including: Daily consumption of substantial quantities of spicy or stimulating foods, high-sugar, high-salt diets, selective eating (such as exclusively meat-based or vegetarian diets), binge eating, excessive alcohol consumption and irregular sleep patterns; coexisting diseases, including respiratory disorders such as bronchiectasis, bronchial asthma, active pulmonary tuberculosis and malignant tumors; metabolic disorders including diabetes, renal disease and liver disease; and immunodeficiency-related ailments including malignancies(such as lung cancer, lymphoma, and leukemia), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and renal insufficiency.

Based on the frequency of previous acute exacerbations, patients with stable COPD were categorized into two groups as follows: The COPD-FE group, which included patients that had experienced two or more exacerbations annually over the last 2 years, and the non-frequent exacerbations of COPD (COPD-NE) group, which included patients that had experienced less than two exacerbations per year in the same period (19). A recent acute exacerbation was characterized as occurring ≥4 weeks after the conclusion of treatment for the previous exacerbation or ≥6 weeks after the onset of the exacerbation, to help differentiate between treatment failure and new acute exacerbations (20). Trained researchers and attending physicians strictly adhered to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The present study is an observational study involving data collection from enrolled patients during a specific time period. It incorporates retrospective elements by reviewing past occurrences of disease exacerbations.

Clinical data collection

Physical examinations, including height, weight and blood pressure; pulmonary function tests; chest X-rays; laboratory tests, including complete blood counts, liver and kidney function assessments; and electrocardiograms were conducted. Additionally, a comprehensive questionnaire was distributed, for the collection of demographic information, medical history, medication usage, smoking status and results from standardized assessments, such as the CAT, mMRC dyspnea scale and a 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) questionnaire. The clinical data collection included clinical indicators, such as BMI, FEV1% predicted (FEV1% pred), CAT score, mMRC score, NLR and PLR, which are linked to the risk of acute exacerbations. Notably, the SF-36 questionnaire evaluated the physical, mental and social well-being of the patients across nine dimensions (21): Physical function (PF), role limitations due to physical problems (role-physical) (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social function (SF), role limitations due to emotional problems (role-emotional) (RE), mental health (MH) and health transition (HT). The scoring for each dimension of the SF-36 scale is obtained through statistical analysis using an online website (medsci.cn/).

Reagents and equipment

The following reagents and equipment were used. QTRAP 5500 mass spectrometer (SCIEX), Nexera X2 LC-30AD UPLC system (Shimadzu Corporation), Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (Waters Corporation), acetonitrile (cat. no. 1499230-935; Merck KGaA), methanol (cat. no. 1.06007.4008; Millipore), ammonium hydroxide solution (cat. no. 105426; Merck), acetonitrile (cat. no. 1.00030.4008; Millipore), formic acid (cat. no. 111670; Millipore), and ammonium acetate (cat. no. 73594; Sigma).

UPLC-MS/MS analysis

Peripheral venous blood was collected from patients in the morning, following an overnight fast lasting between 8 and 12 h, and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to separate the serum. Serum samples were aliquoted into frozen tubes and stored at −80°C. Metabolites were extracted from the serum using 1 ml pre-cooled ethanol/acetonitrile/water (v/v, 2:2:1) by sonication at a frequency of 53 kHz for 1 h in an ice bath, followed by incubation at −20°C for 1 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for UPLC-MS/MS analysis. To ensure data quality, quality control (QC) samples by pooling aliquots from all individual samples for normalization. These were analyzed alongside experimental samples in each batch. Dried extracts were dissolved in 50% acetonitrile, filtered, and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Metabolites were analyzed using a Shimadzu Nexera X2 LC-30AD UPLC system equipped with an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1×50 mm) and a 5500 QTRAP triple quadruple mass spectrometer. The UPLC HSS T3 column was maintained at 40°C with a flow rate of 200 µl/min. The sample volume injected was 5 µl. Mobile phase A comprises a 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution, while mobile phase B is acetonitrile. In positive ion mode, the gradient elution program is as follows: 0–2.5 min, 0% B; 2.5–9 min, linear increase from 0 to 30% B; 9–10 min, linear increase from 30 to 100% B; 10–15.4 min, holding at 100% B; 15.4–15.5 min, linear decrease from 100 to 0% B; and 15.5–18 min, holding at 0% B. In negative ion mode, the gradient elution program is: 0–2 min, 0% B; 2–2.5 min, linear increase from 0 to 20% B; 2.5–3.5 min, linear increase from 20 to 40% B; 3.5–4.5 min, linear increase from 40 to 50% B; 4.5–10 min, linear increase from 50 to 100% B; 10–15.4 min, holding at 100% B; 15.4–15.5 min, linear decrease from 100 to 0% B; and 15.5–18 min, holding at 0% B. Metabolites were detected in both electrospray negative-ionization and positive-ionization modes. During acquisition, QC samples were intermittently injected. Detection of transitions was performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The detailed m/z information of identified metabolites is in Table SI.

Prior to analysis, the raw data was normalized using cumulative sum scaling (CSS). Differential metabolites were identified using statistically significant Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) values derived from the Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) model. Subsequently, permutation tests were performed to validate the stability and reliability of the OPLS-DA model. A two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was applied to the normalized data, and in cases where the assumptions for the t-test were not met, a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. Metabolites with a VIP value >1 and P<0.05 were considered to have a statistically significant difference.

Enrichment analysis

Metabolite data analysis was performed using the Human Metabolome Database (http://www.hmdb.ca/), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://kegg.jp), and MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (metaboanalyst.ca/). Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) and Metabolite Pathway Analysis (MetPA) were conducted with MetaboAnalyst 5.0. Differential metabolites underwent KEGG pathway analysis. MetPA used the relative-betweenness centrality calculation method, while KEGG enrichment analysis used Fisher's exact test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference for enriched pathways.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median (IQR), and categorical variables are presented as counts (%). The clinical data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 26, IBM Corporation). For normally distributed data with homogeneity of variance, a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was applied; otherwise, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. Categorical variable data were tested using Fisher's exact test. Differential metabolites underwent cluster analysis and Spearman's correlation analysis using R software (version 4.0.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Univariate ROC curve analysis was conducted using the MetaboAnalyst web service (metaboanalyst.ca/). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The study comprised 30 patients in the internal cohort, divided into two groups: 15 patients in the COPD-FE group experienced a median of 3 acute exacerbations annually over the past 2 years (IQR=1), while the COPD-NE group consisted of 15 patients with no exacerbations during the same period. No significant differences were demonstrated between the two groups regarding age, sex, BMI, smoking status, medication use or GOLD spirometry grade during stable periods (Table I).

Table I.

Characteristics and clinical indicators of the patients.

| Variable | COPD-NE (n=15) | COPD-FE (n=15) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71.0 (8.0) | 70.0 (5.0) | 0.812a |

| Male | 13 (86.6%) | 11 (73.3%) | 0.651 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.3 (6.8) | 23.4 (5.5) | 0.961b |

| Smoking history | |||

| Never smoked | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.484 |

| Current smoker | 3 (20.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | |

| Former smoker | 7 (46.7%) | 10 (66.7%) | |

| Medication use | |||

| LAMA | 8 (66.7%) | 6 (50.0%) | 0.794 |

| ICS | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| ICS/LABA | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

| ICS/LABA+LAMA | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| None | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Exacerbation predictors | |||

| FEV1% pred | 54.7 (43.1) | 48.7 (17.1) | 0.486b |

| CAT score | 13 (8) | 26 (6) | 0.001b |

| mMRC score | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.011b |

| NLR | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0.019b |

| PLR | 108.3 (50.3) | 134.2 (67.8) | 0.325b |

| SF-36 score | |||

| Physical functioning | 75.0 (30.0) | 40.0 (30.0) | 0.002b |

| Role-physical | 75.0 (100.0) | 0.0 (25.0) | 0.026b |

| Bodily pain | 84.0 (28.0) | 64.0 (32.0) | 0.116b |

| General health | 52.0 (7.0) | 45.0 (10.0) | 0.007b |

| Vitality | 70.0 (25.0) | 55.0 (35.0) | 0.045b |

| Social functioning | 77.9 (22.2) | 55.6 (33.3) | 0.013b |

| Role-emotional | 100.0 (33.3) | 100.0 (100.0) | 0.412b |

| Mental health | 76.0 (20.0) | 68.0 (28.0) | 0.683b |

| Health transition | 50.0 (50.0) | 25.0 (75.0) | 0.202b |

Continuous variables were analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test

under assumptions of normality and variance homogeneity, otherwise Mann-Whitney U test

was applied. Categorical variables were tested with Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables are presented as the median (IQR); categorical variables are presented as counts (%). FEV1% pred, predicted value of forced expiratory volume in 1 sec; IQR, interquartile range; SF-36, 36-item short-form health survey; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FE, frequent exacerbation; NE, non-frequent exacerbation; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; CAT, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

After enrolment, clinical data related to COPD exacerbation risk were collected and analyzed. The results demonstrated that CAT scores, mMRC scores and NLR levels were significantly higher in the COPD-FE group compared with those in the COPD-FE group (Table I). These findings align with prior research in showing similar expression trends of these indicators in COPD-FE patients (9–11). Furthermore, the SF-36 questionnaire was used to assess disease impact demonstrating significantly lower scores in PF, RP, GH, VT and SF for the COPD-FE group compared with those in the COPD-NE group; however, BP, RE, MH and HT scores did not demonstrate a significant difference (Table I). These findings imply a potential association between frequent exacerbations and a decline in physical health, social function and emotional well-being in patients with COPD.

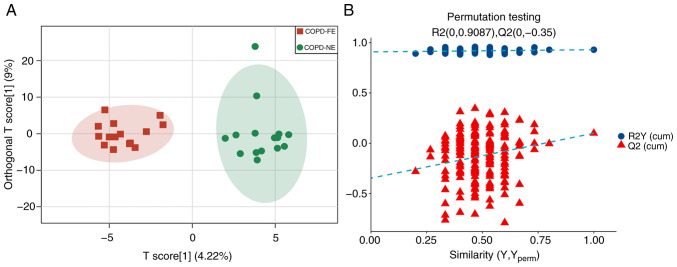

Metabolic profiles of serum samples

Serum samples from enrolled patients were analyzed using UPLC-MS/MS with MRM scanning mode. The OPLS-DA model demonstrated differences in serum metabolites between the COPD-FE and COPD-NE groups, with R2Y(cum)=0.93 and Q2(cum)=0.1 (Fig. 1A). Permutation tests validated the stability and reliability of the model. Comparison of permutation test results with the original Q2(cum) value showed that in all 200 permutation tests, the Q2 values were lower than the original Q2 value, indicating a certain degree of stability and reliability of the model (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Serum sample metabolic profiles. (A) Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis plots of the COPD-FE (green) and COPD-NE (red) groups. (B) Permutation test plots of the two groups. R2 measures model fit and Q2 measures prediction ability. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FE, frequent exacerbation; NE, non-frequent exacerbation.

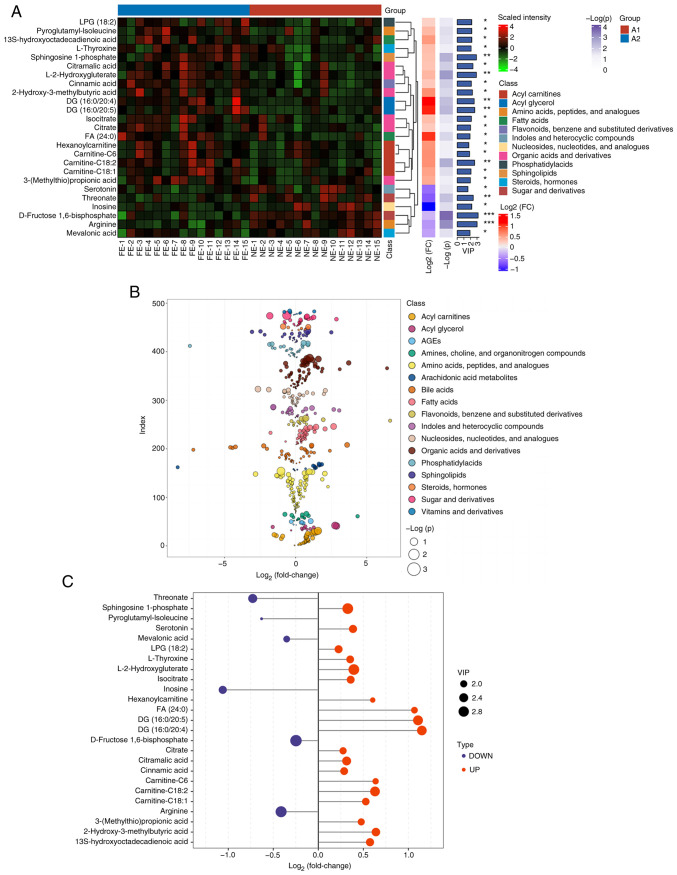

Differential metabolites between the COPD-FE and COPD-NE groups

In the present study, 484 metabolites were detected using a widely targeted metabolomics approach. The significant differences in the levels of 25 metabolites between the COPD-FE and COPD-NE groups were determined using multivariate analysis (OPLS-DA) and univariate analysis methods (two-tailed t-test or Mann-Whitney U test). In the COPD-FE group, the levels of 19 metabolites, including diacylglycerol (DG; 16:0/20:4), DG (16:0/20:5), fatty acid (FA; 24:0) and carnitine-C6, were significantly increased, while six metabolites, including inosine, threonate, serotonin and arginine, were significantly reduced compared with in the COPD-NE group. The heatmap depicts the distribution of these differential metabolites in the samples, demonstrating the patterns between the two groups (Fig. 2A). Additionally, scatter plots illustrate the classification of metabolites and their differences in expression (Fig. 2B). The significance of the differential metabolites is visually represented through bar graphs (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Differential metabolites between the frequent exacerbation of COPD and non-frequent exacerbation of COPD phenotypes. (A) Complex heatmap of differential metabolites based on hierarchical clustering. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (B) Categorical scatter plot of metabolites based on univariate statistical analysis. (C) Bar graph shows the log2 (fold change) and VIP values for the differential metabolites. VIP, variable influence on projection; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

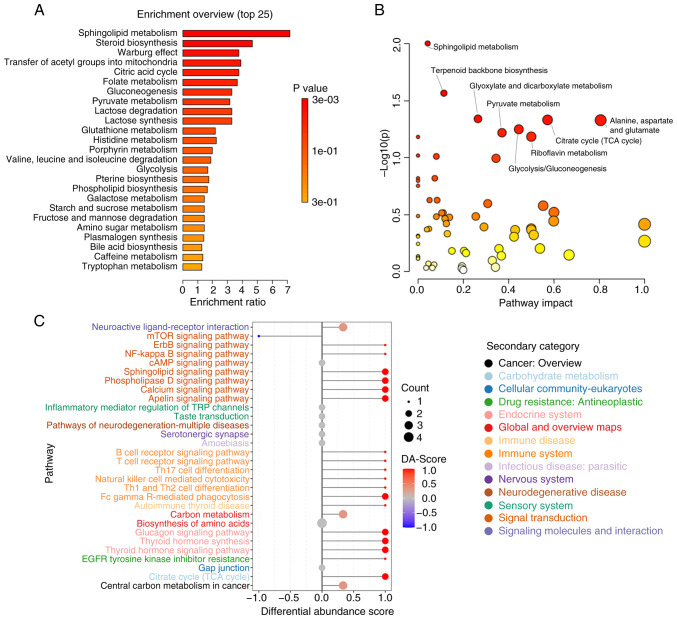

Comprehensive metabolic pathway analysis

The detected metabolites were analyzed using MSEA, MetPA and KEGG methods. The MSEA revealed significant enrichment of multiple metabolic pathways in the COPD-FE group compared to the COPD-NE group, including ‘Sphingolipid Metabolism’, ‘Steroid Biosynthesis’, ‘Warburg Effect’, ‘Transfer of Acetyl Groups into Mitochondria’, and ‘Citric Acid Cycle (TCA cycle)’ (Fig. 3A). MetPA analysis further validated the enrichment of ‘Sphingolipid Metabolism’ and ‘Citrate cycle (TCA cycle)’ as identified in the MSEA analysis and demonstrated additional significant enrichment in pathways such as ‘Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism’, as well as ‘Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism’ (Fig. 3B). KEGG analysis corroborated the importance of ‘Sphingolipid Metabolism’ and ‘TCA cycle’, while also revealing new significantly enriched pathways including ‘Biosynthesis of amino acids’ and ‘Central carbon metabolism in cancer’. Moreover, pathways related to immune inflammation, such as ‘Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis’ and ‘Inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels’ were also significantly enriched in the COPD-FE group (Fig. 3C). This suggested the crucial role of immune inflammation in COPD development. The detailed analysis is listed in Table SII, Table SIII, Table SIV.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive metabolic pathway analysis. (A) Bar plot presenting the top 25 enriched pathways of metabolites from metabolite set enrichment analysis. (B) Scatter plot representing the overall enrichment of metabolic pathways from metabolomic pathway analysis. (C) DA-Score plot showcasing the top 30 pathways with significant enrichment of differential metabolites from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis. DA-Score, Differential Abundance Score. A score of 1 indicates up-regulation across all identified metabolites in the pathway, while-1 indicates down-regulation.

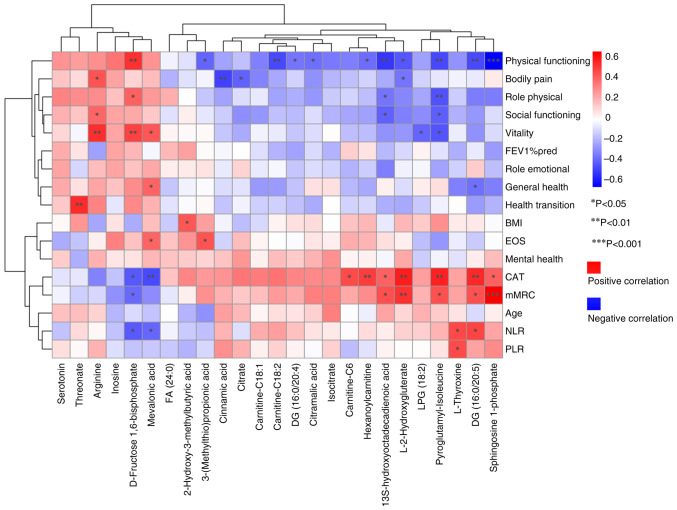

Correlation analysis between differential metabolites and clinical indicators

Spearman's correlation analysis demonstrated associations between metabolite levels and clinical indicators. As shown in Fig. 4, out of the 25 differential metabolites, 12 demonstrated significant correlations with clinical indicators of COPD exacerbation risks. Additionally, the associations between differential metabolites and numerous dimensions of SF-36 scores were assessed, providing insights into the potential impact on overall health.

Figure 4.

Spearman's correlation analysis between differential metabolites and clinical indicators. Red indicates a positive correlation and blue indicates a negative correlation; the darker the color, the greater the correlation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. FA, fatty acid; DG, diacylglycerol; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; CAT, COPD assessment test; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI, body mass index; FEV1% pred, predicted value of forced expiratory volume in 1 sec.

Notably, L-2-hydroxyglutarate (L-2HG), sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), pyroglutamyl-isoleucine and 13S-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid were significantly positively correlated with CAT and mMRC scores, and significantly negatively correlated with PF score. Carnitine-related differential metabolites exhibited similar trends; DG (16:0/20:5) was significantly positively correlated with CAT, mMRC and NLR, but negatively correlated with PF and GH scores. Similarly, L-thyroxine was significantly positively correlated with NLR and PLR, whereas mevalonic acid and D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate were significantly negatively correlated with CAT and NLR. Threonate, arginine, inosine and serotonin were associated with CAT and mMRC scores, although these associations did not reach statistically significant correlation levels (|R|<0.3). Similarly, threonate, arginine, inosine and serotonin were associated with PF, GH, RP and SF scores. The full results are included in Fig. 4 and Table SV.

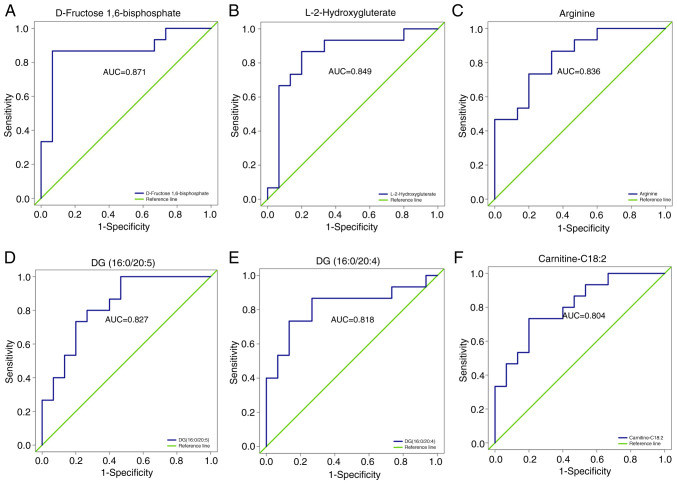

ROC analysis of differential metabolites

ROC analysis was used to validate the ability of metabolites to differentiate between the COPD-NE and COPD-FE groups. Out of the 25 differential metabolites, 18 exhibited an area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of >0.7, demonstrating substantial predictive capacity. Specifically, six differential metabolites had an AUC value >0.8: D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (AUC=0.871), L-2HG (AUC=0.849), arginine (AUC=0.836), DG (16:0/20:5) (AUC=0.827), DG (16:0/20:4) (AUC=0.818) and carnitine-C18:2 (AUC=0.804), demonstrating their predictive capacity between the two groups. The full results are included in Fig. 5 and Table SVI.

Figure 5.

ROC analysis of differential metabolites. ROC curves for (A) D-Fructose 1,6-Bisphosphate, (B) L-2-Hydroxyglutarate, (C) Arginine, (D) DG(16:0/20:5), (E) DG(16:0/20:4), and (F) Carnitine C18:2 are presented to distinguish between frequent and non-frequent exacerbation phenotypes of COPD. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DG, diacylglycerol; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve.

External cohort validation of the metabolomics results

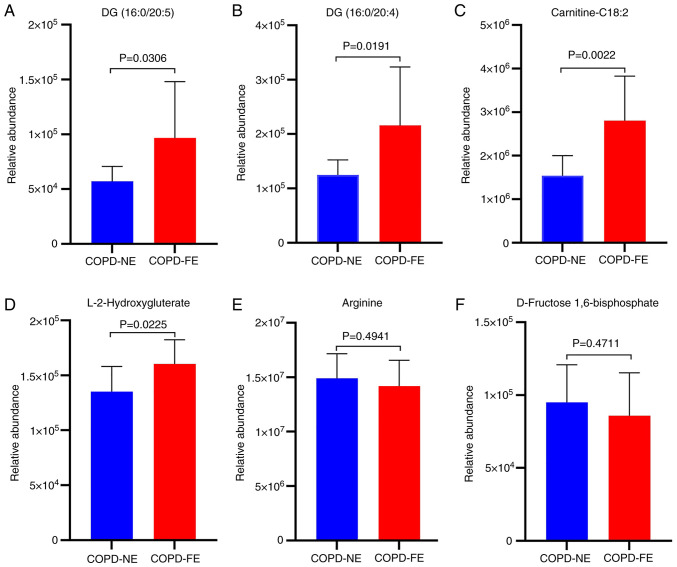

Based on the ROC analysis results, external cohort validation was conducted for six differentially expressed metabolites with AUC values >0.8 using UPLC-MS/MS and MRM scanning modes. The external validation cohort consisted of 10 patients with COPD-NE and 10 patients with COPD-FE. Baseline comparisons were performed, revealing no statistically significant differences in age, sex, BMI, smoking history, medication usage, as well as FEV1% pred and FEV1/FVC ratio between the two groups (Table SVII). External validation results demonstrated significant upregulation of DG (16:0/20:5), DG (16:0/20:4), carnitine-C18:2 and L-2HG in the COPD-FE group compared with in the COPD-NE group (Fig. 6). Conversely, arginine and D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate demonstrated a decreased expression in the COPD-FE group; however, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 6). The extracted ion chromatograms for the six differentially expressed metabolites are shown in Fig. S1.

Figure 6.

Bar charts illustrate the levels of metabolites. (A) DG (16:0/20:5), (B) DG (16:0/20:4), (C) carnitine-C18:2, (D) L-2-hydroxyglutarate, (E) arginine and (F) D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate in the external validation cohort. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DG, diacylglycerol; FE, frequent exacerbation; NE, non-frequent exacerbation.

Discussion

The impact of frequent acute exacerbations on COPD progression is well-established (3,4). Assessing the mechanisms of the COPD-FE phenotype and identifying relevant biomarkers is required for advancing COPD management strategies. The present study used widely targeted metabolomics techniques to analyze serum samples from patients with stable COPD-FE and COPD-NE, identifying 484 metabolites. The subsequent application of the OPLS-DA model demonstrated significant disparities in serum metabolites between the two cohorts. Permutation tests further validated these findings to ensure the model's reliability. The present study identified 25 metabolites with significant differences between the COPD-FE and COPD-NE groups, demonstrating metabolic adaptations in patients with COPD-FE and their potential role in underlying pathogenic mechanisms.

MSEA, MetPA and KEGG analyses were conducted to assess the enrichment of metabolic pathways in the COPD-FE phenotype, providing insights into its underlying mechanisms. The findings of the present study demonstrated significant enrichment in lipid, energy and amino acid metabolism pathways. Furthermore, KEGG analysis revealed the enrichment of immune and inflammatory-related pathways, with all three analytical approaches highlighting enrichment in the ‘sphingolipid metabolism’ pathway. These findings suggested its involvement in COPD-FE pathogenesis. COPD, characterized by persistent inflammation, immune dysregulation and heightened oxidative stress, involves programmed cell death, and atypical proliferation of airway and lung parenchymal cells (22). Sphingolipids are bioactive molecules that are crucial in numerous biological processes (23). S1P, ceramide-1-phosphate and ceramide form the ‘sphingolipid rheostat’, which has garnered attention in respiratory medicine due to its association with pulmonary inflammation and cell cycle regulation (24–26). Sphingolipids may serve as potential targets for predicting exacerbations of COPD (18,27), which is consistent with our study findings. Therefore, investigating dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism and its potential impact on immune and inflammatory regulation in the context of the COPD-FE phenotype may hold significant importance for the prevention and treatment of AECOPD.

The role of energy metabolism in COPD is significant (28). Dysregulation of mitochondrial energy metabolism in COPD is influenced by oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, hypoxia and heightened energy expenditure (29,30). The present study identifies significant enrichment of energy metabolism pathways in COPD-FE, with the ‘TCA cycle’ pathway commonly enriched across all three analytical methods. The TCA cycle serves a central role in cellular metabolism, regulating bioenergetics, biosynthesis and redox balance (31,32). A previous study detected higher resting energy expenditure in patients with COPD compared with that in healthy individuals (33). The present study proposed that frequent acute exacerbations may further increase resting energy expenditure, leading to the accumulation of TCA cycle intermediates and the disruption of anaerobic glycolytic pathways in patients with COPD (34,35). Additionally, the disruption of the TCA cycle has been shown to be associated with the severity of lung function decline and increased mortality risk in patients with COPD (36). Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of energy metabolism disruptions in numerous stages and subgroups of COPD, coupled with research into the role of metabolic reprogramming in the regulation of energy metabolism and TCA cycle intermediates, is required for achieving personalized management of patients with COPD.

The results from MetPA and KEGG analyses demonstrated disruptions in amino acid metabolism within the COPD-FE phenotype. Diminished expression of numerous amino acids, particularly branched-chain amino acids, has been documented in individuals with COPD, demonstrating significant differences between acute exacerbation and stable phases (37,38). Decreased serum concentrations of tryptophan, leucine and valine have been independently associated with frequent acute exacerbations in COPD (39). The results of the present study demonstrated an enrichment of ‘Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism’ and ‘Biosynthesis of amino acids’ pathways in the COPD-FE group. These metabolic pathways serve numerous biological functions, including amino acid metabolism, nitrogen equilibrium, energy generation and physiological processes related to oxidative stress (40,41), suggesting their potential roles in the pathogenic mechanisms of the COPD-FE phenotype. The depletion of arginine in COPD-FE is regulated by arginase, which may be associated with factors such as chronic hypoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation (42–44). Previous research has demonstrated that arginine serves a role in regulating the innate immune response in macrophages by facilitating the activation of MAPK and the production of cytokines (45). Furthermore, arginine influences T-cell function by modulating the cycle of CD3ζ internalization and subsequent re-expression (46). Administration of arginine treatment has been reported to alleviate lung inflammation and airway remodeling (47) and improve cardiopulmonary health in patients with COPD (48). Therefore, increasing arginine levels could potentially serve as a therapeutic approach for COPD-FE.

KEGG analysis also demonstrated the enrichment of pathways such as ‘Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis’ and ‘Inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels’. These findings suggested that immune and inflammation-related pathways potentially influence the pathogenesis of COPD-FE, impacting the pathological mechanisms of the disease. The involvement of Fc gamma R (FcγR) in facilitating antibody-antigen complexes and cellular effector functions, as the Fc receptor for immunoglobulin G (49), is essential for mediating phagocytosis by monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils, and is important in immune responses and inflammation. Consequently, the demonstrated enrichment of FcγR in patients with COPD-FE may suggest the activation of a self-protective mechanism. TRP channels, known for their role as regulating ion channels, substantially influence intricate cellular signaling cascades within the pulmonary system and serve as pathways for mediating pulmonary toxicity. Their activation in response to stimuli such as hypoxia and endotoxins triggers the influx of calcium ions. This compromises the integrity of lung cell barriers, thereby instigating immune dysregulation, inflammation, cellular demise and edema within the lungs (50–52). However, additional empirical evidence is necessary to substantiate these findings and to better comprehend the specific functions of immune and inflammation-related pathways in COPD-FE. The three different analytical approaches used in the present study comprehensively assessed the enrichment of metabolic pathways, providing valuable insights for future research into the pathological mechanisms of COPD-FE.

Through Spearman's correlation analysis, associations between metabolites and clinical indicators of acute exacerbations of COPD were identified. The significant positive correlations demonstrated between S1P and L-2HG with CAT and mMRC scores suggest their potential as biomarkers for assessing the risk of acute exacerbations and evaluating symptoms. Furthermore, these metabolites demonstrated negative associations with numerous dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire, indicating their potential involvement in the deterioration of the overall health of patients with COPD. S1P is a bioactive lipid mediator that is produced by the phosphorylation of sphingosine by sphingosine kinases (SphK). The accumulation of S1P signifies disruptions in sphingolipid metabolism, potentially attributed to recurrent infections or acute lung injuries (53–55). Respiratory infections are common triggers of AECOPD. The SphK/S1P axis has been reported to regulate the host immune system and to exert pro- or anti-viral effects in different types of viral infections by interfering with intracellular signaling pathways (56,57). For example, S1P can enhance endothelial barrier function and epithelial cell survival during respiratory syncytial virus infection by activating the Akt/ERK signaling pathway (58,59). Therefore, the role of S1P in respiratory infections in patients with COPD-FE phenotype requires further investigation. CAT and mMRC scores reflect the clinical symptoms and the severity of breathlessness in patients. Chronic inflammation is the primary mechanism leading to the decline in lung function and worsening of the condition in patients with COPD. S1P modulates immune cell recruitment, proliferation, migration and bidirectional regulation of inflammatory processes by binding to G protein-coupled S1P receptors (60–62). Recently, it has been reported that in COPD, S1P inhibits histone deacetylase 1 activity, drives alveolar macrophage polarization towards the pro-inflammatory M1 type and promotes inflammatory cytokine release (63). Elevated S1P levels have been demonstrated to contribute to airway cholinergic hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of COPD, exacerbating airway constriction and facilitating remodeling (64). These studies partially reveal the association between S1P and worsening dyspnea and frequent acute exacerbations in COPD. In-depth study of the expression and function of the S1P pathway in different stages and phenotypes of COPD, elucidation of the regulatory network between S1P and COPD-FE, and exploration of its underlying molecular mechanisms will be the research focus of future work.

Existing research has suggested that hypoxia and mitochondrial stress contribute to increased L-2HG levels (65,66). The demonstrated positive association between L-2HG levels and the intensity of breathlessness implies its potential role as an adaptive reaction to hypoxia. L-2HG alleviates hypoxia-induced mitochondrial damage by inhibiting glycolysis and regulating oxidative phosphorylation (67). Moreover, L-2HG levels influence immune cells, specifically promoting Th17 cell differentiation, enhancing the stability of HIF-1α to facilitate the activation of inflammatory macrophages, thereby promoting the expression of inflammatory factors (68,69). A more comprehensive investigation is necessary to elucidate the exact involvement of L-2HG in the pathological mechanisms of COPD-FE. The present study demonstrated an elevation in carnitine metabolite levels among patients with COPD-FE, showing positive associations with CAT scores and negative associations with Physical Functioning. This abnormal metabolic profile highlights disruptions in mitochondrial energy processes (70), potentially contributing to a decline in lung function (71). Research has indicated that L-carnitine can mitigate apoptosis in alveolar type II (ATII)-like LA4 cells induced by PPE and H2O2 (72). Furthermore, carnitine metabolism is recognized for its significant regulatory function in processes associated with inflammation and oxidative stress (73,74). These mechanisms could provide valuable insights into the reported associations.

Clinical studies have demonstrated that NLR and PLR are valuable predictive indicators for COPD prognosis and the likelihood of acute exacerbations (11). Furthermore, evidence has suggested an association between thyroid function and COPD severity and prognosis (75–77). The results of the present study demonstrated a significant positive correlation between L-thyroxine levels with NLR and PLR, suggesting the potential of L-thyroxine as a predictive factor for frequent exacerbations in individuals with COPD. In contrast to individuals with COPD-NE, the increased concentrations of L-thyroxine in patients with COPD-FE may indicate physiological adjustments in response to recurrent acute exacerbations. Although thyroid hormones are suggested to serve a role in energy metabolism, inflammation and airway remodeling (78,79), their specific influence in the pathogenesis of COPD-FE remains uncertain, requiring additional research to clarify underlying mechanisms. DG, produced through phosphatidylinositol metabolism, is a lipid secondary messenger activated by extracellular stimuli (80). The innate and adaptive immune systems are crucial mechanisms for protecting against external pathogens. In the intricate signaling pathways, DG, under the regulation of DG kinase, serves a significant role, particularly in modulating immune responses such as antimicrobial autophagy, Th1/Th17 cell differentiation, neutrophil function and proliferation (81–83). The outcomes of the present study demonstrate a positive association between DG (16:0/20:5) and NLR and PLR, highlighting the requirement for further investigation into the role of DG (16:0/20:5) in modulating immune responses in COPD-FE. Furthermore, the levels of D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate demonstrated a significant negative correlation with NLR, CAT and mMRC scores, while displaying a significant positive correlation with PF and VT scores in patients with COPD-FE. This correlation could be associated with diminished D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate levels in the physiological system of patients with COPD-FE, attributable to factors including hypoxia, disrupted glycolysis and oxidative stress (84). Diminished D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate levels may disrupt sugar metabolism and energy provision, potentially impacting the quality of life of patients. Nevertheless, further investigation is essential to fully comprehend the underlying mechanisms. In summary, the application of Spearman's correlation analysis provided initial insights into the intricate correlation between metabolic disturbances and the propensity for recurrent acute exacerbations in individuals with COPD. Subsequent investigations should prioritize elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these connections and exploring their potential applications in COPD treatment.

ROC analysis was performed on the 25 identified differential metabolites. Among them, six metabolites, including D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, arginine, L-2HG, DG (16:0/20:5), DG (16-0/20:4) and carnitine-C18:2 demonstrated AUC values >0.8, indicating their discriminatory ability between COPD-FE and COPD-NE groups. External validation of these metabolites demonstrated a significant upregulation of DG (16:0/20:5), DG (16:0/20:4), carnitine-C18:2 and L-2HG in patients with COPD-FE compared with in those with COPD-NE. While D-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate and arginine did not exhibit a significant decrease in expression in the external validation cohort, their trends aligned with the internal validation cohort. These consistent trends underscore the relevance of these metabolites in predicting the risk of exacerbations. The concordance between internal metabolomics analysis results and external validation supports these identified metabolites as potential biomarkers for COPD-FE, guiding future research into their roles and pathways, contributing to developing more refined predictive models and increasing the understanding of COPD pathophysiology. In the external cohort, the results were consistent with those of the internal cohort. This served as a partial alleviation of the limitations identified in the internal cohort, thereby offering supplementary evidence for the dependability and replicability of the present research results.

The present study possesses both limitations and strengths. Despite controlled inclusion criteria to minimize confounding factors, the limited sample size may have reduced the statistical power and robustness of the ROC results. However, the consistency between external validation results and internal cohort findings enhances the reliability of the conclusions of the present study. Furthermore, the interpretability of the findings supports publication, as the present study represents a primary and exploratory effort aiming to provide foundational knowledge for future research. A history of previous acute exacerbations is a recognized independent risk factor for predicting future exacerbations (2,85). However, the present study excluded patients with COPD experiencing only one acute exacerbation annually, potentially limiting the understanding of differences among patients with varied exacerbation frequencies and reducing the comprehensiveness of the study. Additionally, the study exclusively included Chinese Han participants, limiting the generalization of the findings. Future research will focus on expanding the sample size, investigating pathological differences among patients with COPD with diverse exacerbation frequencies and severity, and include more representative populations to enhance the applicability of these findings.

The present study used the comprehensive targeted metabolomics technique based on UPLC-MS/MS to detect serum differential metabolites in patients with stable-phase COPD-FE. This differs from previous research in terms of the technology used, the disease stage of the subjects (stable phase instead of acute exacerbation), and the specific focus on the COPD-FE phenotype (15,17,39,86). In comparison to prior studies, the present study used more comprehensive bioinformatics methods, including MSEA, MetPA and KEGG analyses. This allowed the present analysis to cover both differentially and non-differentially expressed metabolites, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of potential changes in metabolic pathways. The present study analyzed the correlation between differential metabolites and clinical indicators predicting acute exacerbations. Through ROC analysis and external cohort validation, the potential of these metabolites as biomarkers and therapeutic targets was emphasized. Furthermore, by examining the correlation between differential metabolites and SF-36 scores, a comprehensive exploration of the association between metabolites, and both physical and psychological health was provided.

In conclusion, the present study highlights the significant differences in metabolite expression between COPD-FE and COPD-NE groups. Disruptions in lipid, energy and amino acid metabolism pathways were revealed to be the primary defining features of the COPD-FE phenotype. Importantly, metabolites such as DG (16:0/20:5), DG (16:0/20:4), carnitine-C18:2 and L-2HG were demonstrated as potential biomarkers for predicting the risk of COPD-FE. The present study lays the foundation for further pathological investigations, developing risk prediction models and implementing personalized management approaches targeting the COPD-FE phenotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Qi Yaoxin from Shanghai Bioprofile Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, for providing valuable technical support in mass spectrometry.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AECOPD

acute exacerbations of COPD

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

bodily pain

- CAT

COPD assessment test

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COPD-FE

frequent exacerbation of COPD

- COPD-NE

non-frequent exacerbation of COPD

- DG

diacylglycerol

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- GH

general health

- GOLD

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- HT

health transition

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- L-2HG

L-2-hydroxyglutarate

- MetPA

Metabolite Pathway Analysis

- MH

mental health

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- MSEA

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis

- PF

physical functioning

- PLR

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- RE

role emotional

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- RP

role physical

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SF

social functioning

- SF-36

36-item short-form health survey

- UPLC-MS/MS

ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- VIP

Variable Importance in Projection

- VT

vitality

Funding Statement

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Joint Key Project (grant no. U20A20398) and the 2022 Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (grant no. 2208085QH264).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the MetaboLights repository under the accession number MTBLS9119. The data can be accessed at the following URL: www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS9119.

Authors' contributions

ZGL and HZD conceived the study. HZD and HW designed the methodology and wrote the manuscript. HZD, HW, FCZ and DW analyzed data. HZD, HW, DW, YTG and JBT performed experiments. HZD, DW and JZ interpreted data. HZD, HW and JZ reviewed the manuscript. HZD, HW and FCZ visualized data. JBT and ZGL supervised the study. DW and ZGL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Hefei, China; approval no. 2021AH-31) and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines outlined in The Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written informed consent to the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), corp-author GOLD; Fontana, WI: 2020. [ February 15; 2020 ]. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2020 report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dransfield MT, Kunisaki KM, Strand MJ, Anzueto A, Bhatt SP, Bowler RP, Criner GJ, Curtis JL, Hanania NA, Nath H, et al. Acute exacerbations and lung function loss in smokers with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:324–330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1014OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA. COPD exacerbations: Defining their cause and prevention. Lancet. 2007;370:786–796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61382-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.France G, Orme MW, Greening NJ, Steiner MC, Chaplin EJ, Clinch L, Singh SJ. Cognitive function following pulmonary rehabilitation and post-discharge recovery from exacerbation in people with COPD. Respir Med. 2021;176:106249. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camac ER, Voelker H, Criner GJ, COPD Clinical Research Network and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Impact of COPD exacerbations leading to hospitalization on general and disease-specific quality of life. Respir Med. 2021;186:106526. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallin R, Koivisto-Hursti UK, Lindberg E, Janson C. Nutritional status, dietary energy intake and the risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Respir Med. 2006;100:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asai N, Ohkuni Y, Ohashi W, Kaneko N. Modified MRC assessment and FEV1.0 can predict frequent acute exacerbation of COPD: An observational prospective cohort study at a single-center in Japan. Respir Med. 2023;212:107218. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cen J, Weng L. Comparison of peak expiratory Flow(PEF) and COPD assessment test (CAT) to assess COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization: A prospective observational study. Chron Respir Dis. 2022;19:14799731221081859. doi: 10.1177/14799731221081859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu JJ, Xu HR, Zhang YX, Li YX, Yu HY, Jiang LD, Wang CX, Han M. The characteristics of the frequent exacerbator with chronic bronchitis phenotype and non-exacerbator phenotype in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A meta-analysis and system review. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20:103. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1126-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Ge H, Feng X, Hang J, Zhang F, Jin X, Bao H, Zhou M, Han F, Li S, et al. The combination of hemogram indexes to predict exacerbation in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:572435. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.572435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen W, Gong L, Guo Z, Wang W, Zhang H, Liu X, Yu S, Xiong L, Luo J. A novel integrated method for large-scale detection, identification, and quantification of widely targeted metabolites: Application in the study of rice metabolomics. Mol Plant. 2013;6:1769–1780. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Q, Song J. Analysis of widely targeted metabolites of the euhalophyte Suaeda salsa under saline conditions provides new insights into salt tolerance and nutritional value in halophytic species. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:388. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2006-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun T, Ding ZX, Luo X, Liu QS, Cheng Y. Blood exosomes have neuroprotective effects in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:3807476. doi: 10.1155/2020/3807476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng L, You H, Xu MY, Dong ZY, Liu M, Jin WJ, Zhou C. A novel metabolic score for predicting the acute exacerbation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:785–795. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S405547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Suresh B, Lim MN, Hong SH, Kim KS, Song HE, Lee HY, Yoo HJ, Kim WJ. Metabolomics reveals dysregulated sphingolipid and amino acid metabolism associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:2343–2353. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S376714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gai X, Guo C, Zhang L, Zhang L, Abulikemu M, Wang J, Zhou Q, Chen Y, Sun Y, Chang C. Serum glycerophospholipid profile in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Physiol. 2021;12:646010. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.646010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Zhang H, Si Y, Du Y, Wu J, Li J. High-coverage lipidomics analysis reveals biomarkers for diagnosis of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2022:1201–1202. 123278. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2022.123278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singanayagam A, Loo SL, Calderazzo M, Finney LJ, Trujillo Torralbo MB, Bakhsoliani E, Girkin J, Veerati P, Pathinayake PS, Nichol KS, et al. Antiviral immunity is impaired in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019;317:L893–L903. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00253.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenferink A, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, Frith PA, Zwerink M, Monninkhof EM, van der Palen J, Effing TW. Self-management interventions including action plans for exacerbations versus usual care in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD011682. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011682.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang R, Wu C, Zhao Y, Yan X, Ma X, Wu M, Liu W, Gu Z, Zhao J, He J. Health related quality of life measured by SF-36: A population-based study in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christenson SA, Smith BM, Bafadhel M, Putcha N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2022;399:2227–2242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:175–191. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ammit AJ, Hastie AT, Edsall LC, Hoffman RK, Amrani Y, Krymskaya VP, Kane SA, Peters SP, Penn RB, Spiegel S, Panettieri RA., Jr Sphingosine 1-phosphate modulates human airway smooth muscle cell functions that promote inflammation and airway remodeling in asthma. FASEB J. 2001;15:1212–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0742fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolly PS, Rosenfeldt HM, Milstien S, Spiegel S. The roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate in asthma. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helke K, Angel P, Lu P, Garrett-Mayer E, Ogretmen B, Drake R, Voelkel-Johnson C. Ceramide synthase 6 deficiency enhances inflammation in the DSS model of colitis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1627. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20102-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowler RP, Jacobson S, Cruickshank C, Hughes GJ, Siska C, Ory DS, Petrache I, Schaffer JE, Reisdorph N, Kechris K. Plasma sphingolipids associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:275–284. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1771OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belchamber KBR, Singh R, Batista CM, Whyte MK, Dockrell DH, Kilty I, Robinson MJ, Wedzicha JA, Barnes PJ, Donnelly LE, COPD-MAP consortium Defective bacterial phagocytosis is associated with dysfunctional mitochondria in COPD macrophages. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1802244. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02244-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haji G, Wiegman CH, Michaeloudes C, Patel MS, Curtis K, Bhavsar P, Polkey MI, Adcock IM, Chung KF, COPDMAP consortium Mitochondrial dysfunction in airways and quadriceps muscle of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2020;21:262. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01527-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou WC, Qu J, Xie SY, Sun Y, Yao HW. Mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic respiratory diseases: Implications for the pathogenesis and potential therapeutics. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:5188306. doi: 10.1155/2021/5188306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-Reyes I, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat Commun. 2020;11:102. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13668-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pålsson-McDermott EM, O'Neill LAJ. Targeting immunometabolism as an anti-inflammatory strategy. Cell Res. 2020;30:300–314. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finamore P, Lattanzi G, Pedone C, Poci S, Alma A, Scarlata S, Fontana DO, Khazrai YM, Incalzi RA. Energy expenditure and intake in COPD: The extent of unnoticed unbalance by predicting REE. Respir Med. 2022;201:106951. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naz S, Kolmert J, Yang M, Reinke SN, Kamleh MA, Snowden S, Heyder T, Levänen B, Erle DJ, Sköld CM, et al. Metabolomics analysis identifies sex-associated metabotypes of oxidative stress and the autotaxin-lysoPA axis in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1602322. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02322-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue M, Zeng Y, Lin R, Qu HQ, Zhang T, Zhang XD, Liang Y, Zhen Y, Chen H, Huang Z, et al. Metabolomic profiling of anaerobic and aerobic energy metabolic pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2021;246:1586–1596. doi: 10.1177/15353702211008808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto-Plata V, Casanova C, Divo M, Tesfaigzi Y, Calhoun V, Sui J, Polverino F, Priolo C, Petersen H, de Torres JP, et al. Plasma metabolomics and clinical predictors of survival differences in COPD patients. Respir Res. 2019;20:219. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1167-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Li Q, Liu C, Pang R, Yin Y. Plasma metabolomics and lipidomics reveal perturbed metabolites in different disease stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:553–565. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S229505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engelen MPKJ, Schols AMWJ. Altered amino acid metabolism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: New therapeutic perspective? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:73–78. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labaki WW, Gu T, Murray S, Curtis JL, Yeomans L, Bowler RP, Barr RG, Comellas AP, Hansel NN, Cooper CB, et al. Serum amino acid concentrations and clinical outcomes in smokers: SPIROMICS metabolomics study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11367. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47761-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pouw EM, Schols AM, Deutz NE, Wouters EF. Plasma and muscle amino acid levels in relation to resting energy expenditure and inflammation in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:797–801. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9708097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sivakumar R, Babu PV, Shyamaladevi CS. Aspartate and glutamate prevents isoproterenol-induced cardiac toxicity by alleviating oxidative stress in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2011;63:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rus A, Peinado MA, Castro L, Del Moral ML. Lung eNOS and iNOS are reoxygenation time-dependent upregulated after acute hypoxia. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010;293:1089–1098. doi: 10.1002/ar.21141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caldwell RB, Toque HA, Narayanan SP, Caldwell RW. Arginase: An old enzyme with new tricks. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bulau P, Zakrzewicz D, Kitowska K, Leiper J, Gunther A, Grimminger F, Eickelberg O. Analysis of methylarginine metabolism in the cardiovascular system identifies the lung as a major source of ADMA. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L18–L24. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00076.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mieulet V, Yan L, Choisy C, Sully K, Procter J, Kouroumalis A, Krywawych S, Pende M, Ley SC, Moinard C, Lamb RF. TPL-2-mediated activation of MAPK downstream of TLR4 signaling is coupled to arginine availability. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra61. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Culotta KS, Hernandez CP, DeSalvo J, Ochoa JB, Park HJ, Zabaleta J, Ochoa AC. L-Arginine modulates CD3zeta expression and T cell function in activated human T lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 2004;232:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pera T, Zuidhof AB, Smit M, Menzen MH, Klein T, Flik G, Zaagsma J, Meurs H, Maarsingh H. Arginase inhibition prevents inflammation and remodeling in a guinea pig model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349:229–238. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.210138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rathor VPS, Chugh P, Ali R, Bhatnagar A, Haque SE, Bhatnagar A, Mittal G. Formulation, preclinical and clinical evaluation of a new submicronic arginine respiratory fluid for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson CL, Shen L, Eicher DM, Wewers MD, Gill JK. Phagocytosis mediated by three distinct Fc gamma receptor classes on human leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1333–1345. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.4.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietrich A, Steinritz D, Gudermann T. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels as molecular targets in lung toxicology and associated diseases. Cell Calcium. 2017;67:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi N, Kozai D, Kobayashi R, Ebert M, Mori Y. Roles of TRPM2 in oxidative stress. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khalil M, Alliger K, Weidinger C, Yerinde C, Wirtz S, Becker C, Engel MA. Functional role of transient receptor potential channels in immune cells and epithelia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:174. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ebenezer DL, Fu P, Suryadevara V, Zhao Y, Natarajan V. Epigenetic regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) in acute lung injury: Role of S1P lyase. Adv Biol Regul. 2017;63:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wadgaonkar R, Patel V, Grinkina N, Romano C, Liu J, Zhao Y, Sammani S, Garcia JG, Natarajan V. Differential regulation of sphingosine kinases 1 and 2 in lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L603–L613. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90357.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng A, Rice AD, Zhang Y, Kelly GT, Zhou T, Wang T. S1PR1-associated molecular signature predicts survival in patients with sepsis. Shock. 2020;53:284–292. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohammed S, Bindu A, Viswanathan A, Harikumar KB. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling during infection and immunity. Prog Lipid Res. 2023;92:101251. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2023.101251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang L, Liu J, Xiao E, Han Q, Wang L. Sphingosine-1-phosphate related signalling pathways manipulating virus replication. Rev Med Virol. 2023;33:e2415. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monick MM, Cameron K, Powers LS, Butler NS, McCoy D, Mallampalli RK, Hunninghake GW. Sphingosine kinase mediates activation of extracellular signal-related kinase and Akt by respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:844–852. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0424OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas KW, Monick MM, Staber JM, Yarovinsky T, Carter AB, Hunninghake GW. Respiratory syncytial virus inhibits apoptosis and induces NF-kappa B activity through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:492–501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Obinata H, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and inflammation. Int Immunol. 2019;31:617–625. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxz037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, Yang C, Liu Y, Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, Horne D, Somlo G, Forman S, et al. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nat Med. 2010;16:1421–1428. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hou L, Zhang Z, Yang L, Chang N, Zhao X, Zhou X, Yang L, Li L. NLRP3 inflammasome priming and activation in cholestatic liver injury via the sphingosine 1-phosphate/S1P receptor 2/Gα(12/13)/MAPK signaling pathway. J Mol Med (Berl) 2021;99:273–288. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-02032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang M, Hei R, Zhou Z, Xiao W, Liu X, Chen Y. Macrophage polarization involved the inflammation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by S1P/HDAC1 signaling. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:4478–4489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Cunto G, Brancaleone V, Riemma MA, Cerqua I, Vellecco V, Spaziano G, Cavarra E, Bartalesi B, D'Agostino B, Lungarella G, et al. Functional contribution of sphingosine-1-phosphate to airway pathology in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:267–281. doi: 10.1111/bph.14861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oldham WM, Clish CB, Yang Y, Loscalzo J. Hypoxia-mediated increases in L-2-hydroxyglutarate coordinate the metabolic response to reductive stress. Cell Metab. 2015;22:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Intlekofer AM, Dematteo RG, Venneti S, Finley LW, Lu C, Judkins AR, Rustenburg AS, Grinaway PB, Chodera JD, Cross JR, Thompson CB. Hypoxia induces production of L-2-hydroxyglutarate. Cell Metab. 2015;22:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Intlekofer AM, Wang B, Liu H, Shah H, Carmona-Fontaine C, Rustenburg AS, Salah S, Gunner MR, Chodera JD, Cross JR, Thompson CB. L-2-Hydroxyglutarate production arises from noncanonical enzyme function at acidic pH. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:494–500. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steinert EM, Vasan K, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial metabolism regulation of T cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39:395–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-082015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams NC, Ryan DG, Costa ASH, Mills EL, Jedrychowski MP, Cloonan SM, Frezza C, O'Neill LA. Signaling metabolite L-2-hydroxyglutarate activates the transcription factor HIF-1α in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2022;298:101501. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Almannai M, Alfadhel M, El-Hattab AW. Carnitine inborn errors of metabolism. Molecules. 2019;24:3251. doi: 10.3390/molecules24183251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Y, Li P, Cao Y, Liu C, Wang J, Wu W. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Underlying mechanisms and physical therapy perspectives. Aging Dis. 2023;14:33–45. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Conlon TM, Bartel J, Ballweg K, Günter S, Prehn C, Krumsiek J, Meiners S, Theis FJ, Adamski J, Eickelberg O, Yildirim AÖ. Metabolomics screening identifies reduced L-carnitine to be associated with progressive emphysema. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:273–287. doi: 10.1042/CS20150438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nicholas DA, Proctor EA, Agrawal M, Belkina AC, Van Nostrand SC, Panneerseelan-Bharath L, Jones AR IV, Raval F, Ip BC, Zhu M, et al. Fatty Acid metabolites combine with reduced β oxidation to activate Th17 inflammation in human type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2019;30:447–461.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aguer C, McCoin CS, Knotts TA, Thrush AB, Ono-Moore K, McPherson R, Dent R, Hwang DH, Adams SH, Harper ME. Acylcarnitines: Potential implications for skeletal muscle insulin resistance. FASEB J. 2015;29:336–345. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-255901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okutan O, Kartaloglu Z, Onde ME, Bozkanat E, Kunter E. Pulmonary function tests and thyroid hormone concentrations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13:126–128. doi: 10.1159/000076950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alshamari AHI, Deli F, Kadhum HI, Kadhim IJ. Assessment of thyroid function tests in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Med Life. 2022;15:1532–1535. doi: 10.25122/jml-2022-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dimopoulou I, Ilias I, Mastorakos G, Mantzos E, Roussos C, Koutras DA. Effects of severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on thyroid function. Metabolism. 2001;50:1397–1401. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.28157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dekkers BGJ, Naeimi S, Bos IST, Menzen MH, Halayko AJ, Hashjin GS, Meurs H. L-thyroxine promotes a proliferative airway smooth muscle phenotype in the presence of TGF-β1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L301–L306. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mancini A, Di Segni C, Raimondo S, Olivieri G, Silvestrini A, Meucci E, Currò D. Thyroid hormones, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6757154. doi: 10.1155/2016/6757154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baldanzi G, Malerba M. DGKα in neutrophil biology and its implications for respiratory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5673. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shahnazari S, Namolovan A, Klionsky DJ, Brumell JH. A role for diacylglycerol in antibacterial autophagy. Autophagy. 2011;7:331–333. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang J, Wang HX, Xie J, Li L, Wang J, Wan ECK, Zhong XP. DGK α and ζ activities control TH1 and TH17 cell differentiation. Front Immunol. 2020;10:3048. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cooke M, Kazanietz MG. Overarching roles of diacylglycerol signaling in cancer development and antitumor immunity. Sci Signal. 2022;15:eabo0264. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.abo0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fernie AR, Carrari F, Sweetlove LJ. Respiratory metabolism: Glycolysis, the TCA cycle and mitochondrial electron transport. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Al-ani S, Spigt M, Hofset P, Melbye H. Predictors of exacerbations of asthma and COPD during one year in primary care. Fam Pract. 2013;30:621–628. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cruickshank-Quinn CI, Jacobson S, Hughes G, Powell RL, Petrache I, Kechris K, Bowler R, Reisdorph N. Metabolomics and transcriptomics pathway approach reveals outcome-specific perturbations in COPD. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17132. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35372-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the MetaboLights repository under the accession number MTBLS9119. The data can be accessed at the following URL: www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS9119.