Abstract

Background

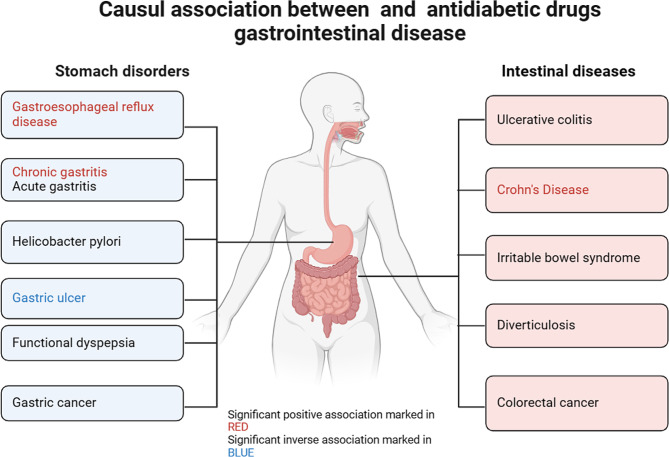

The incidence of diabetic gastrointestinal diseases is increasing year by year. This study aimed to investigate the causal relationship between antidiabetic medications and gastrointestinal disorders, with the goal of reducing the incidence of diabetes-related gastrointestinal diseases and exploring the potential repurposing of antidiabetic drugs.

Methods

We employed a two-sample Mendelian randomization (TSMR) design to investigate the causal association between antidiabetic medications and gastrointestinal disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gastric ulcer (GU), chronic gastritis, acute gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric cancer (GC), functional dyspepsia (FD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease (CD), diverticulosis, and colorectal cancer (CRC). To identify potential inhibitors of antidiabetic drug targets, we collected single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, insulin, and its analogs, thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors from published genome-wide association study statistics. We then conducted a drug-target Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using inverse variance weighting (IVW) as the primary analytical method to assess the impact of these inhibitors on gastrointestinal disorders. Additionally, diabetes was selected as a positive control.

Results

Sulfonylureas were found to significantly reduce the risk of CD (IVW: OR [95% CI] = 0.986 [0.978, 0.995], p = 1.99 × 10− 3), GERD (IVW: OR [95% CI] = 0.649 [0.452, 0.932], p = 1.90 × 10− 2), and chronic gastritis (IVW: OR [95% CI] = 0.991 [0.982, 0.999], p = 4.50 × 10− 2). However, they were associated with an increased risk of GU development (IVW: OR [95%CI] = 2 0.761 [1.259, 6.057], p = 1 0.12 × 10− 2).

Conclusions

The results indicated that sulfonylureas had a positive effect on the prevention of CD, GERD, and chronic gastritis but a negative effect on the development of gastric ulcers. However, our research found no causal evidence for the impact of metformin, GLP-1 agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP 4 inhibitors, insulin and its analogs, thiazolidinediones, or alpha-glucosidase inhibitors on gastrointestinal diseases.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-024-01359-z.

Keywords: Antidiabetic drugs, Diabetes, Gastrointestinal diseases, Drug targets, Mendelian randomization study

Background

According to the United European Gastroenterology, the incidence of gastrointestinal diseases is increasing each year [1]. Studies on the demography of aging in the elderly and the epidemiology of gastrointestinal diseases show a strong association between age and a higher prevalence of these disorders. As the population ages, the prevalence of gastrointestinal diseases is expected to rise [2]. Many factors contribute to the development of gastrointestinal disorders, and research by Babu Krishnan et al. indicates that diabetes can lead to a variety of gastrointestinal complications [3]. A prospective study demonstrated a higher prevalence of GERD symptoms among patients with type 2 diabetes compared to the general population [4]. Additionally, a systematic review of meta-analyses found that diabetes significantly increases the risk of inflammatory bowel disease [5]. Retrospective studies have also shown a correlation between autoimmune gastritis and type 1 diabetes [6]. Furthermore, patients with diabetes are more susceptible to Helicobacter pylori infection [7, 8]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies conducted by Jinru Guo et al. demonstrated that the risk of gastric cancer is higher in individuals with diabetes, with the risk varying based on the duration since the onset of diabetes [9]. Chin-Hsiao Tseng’s population-based analysis in Taiwan similarly suggests that people with diabetes have a higher risk of developing stomach cancer [10, 11]. Moreover, patients with diabetes have a significantly higher risk of death from colon cancer [12]. A Mendelian Randomization (MR) study suggests that type 2 diabetes and impaired glycemic homeostasis raise the risk of gastrointestinal diseases [13]. Antidiabetic drugs may also be linked to gastrointestinal diseases. Animal experiments by Isabela R.S.G Noleto et al. showed that metformin has a protective effect on the gastric mucosa and prevents peptic ulcer formation in hyperglycemic rats [14]. Furthermore, metformin possesses anti-inflammatory properties and is used to treat inflammatory bowel disease [15]. Metformin may reduce the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in people with type 2 diabetes [16]. It also reduces the risk of inflammatory bowel diverticulosis in patients with type 2 diabetes [17]. Retrospective cohort studies have found that metformin reduces the risk of gastric and colorectal cancer in patients with diabetes [18–20]. Additionally, studies have shown that metformin reduces the risk of Helicobacter Pylori (HP) infection [21], and insulin use is significantly associated with a higher incidence of HP eradication [22]. Audrius Dulskas et al. found an increased risk of stomach cancer in patients with diabetes treated with sulfonylureas [23]. However, a retrospective population-based cohort study conducted on the Italian population revealed a reduction in GC risk associated with sulfonylurea usage [24].

Observational studies on the relationship between different antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal disorders have produced controversial results. No studies have yet explored the causal relationship between antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal disorders. MR is an analytical method used to study causal relationships between exposures and clinically relevant outcomes [25]. It can predict adverse drug reactions and provide opportunities for drug repurposing [26]. MR of drug targets can reflect the effects of drug use by using genetic instrumentation within or near the target gene to analyze genetic variants that mimic the pharmacological inhibition of drug targets [27].

In this study, we used SNPs in or near target as pharmacogenetic proxies to explore the causal relationship between antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal diseases including GERD, GU, chronic gastritis, acute gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric cancer, FD, IBS, UC, CD, diverticulosis, and CRC. The results can guide medication choices for patients with diabetes with gastrointestinal complications and suggest potential gastrointestinal prevention strategies for future clinical trials. This can improve the happiness index and quality of life for patients with diabetes, especially elderly people.

Methods

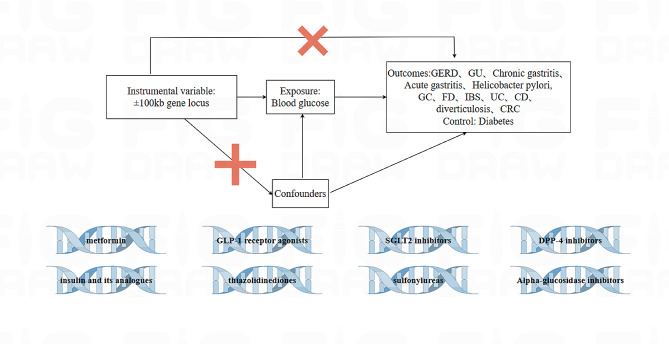

Research design

We estimated the causal relationship between antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal diseases by a TSMR study (Fig. 1). We selected the major antidiabetic drugs, including metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, insulin and its analogs, thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors [28, 29]. Genetic variants associated with blood glucose levels in these drug-target genes were identified to proxy the drug-target effect [27]. We then analyzed the effect of these genetic variants on gastrointestinal disorders using MR.

Fig. 1.

This is a flowchart of the study design and the MR Analysis process

The causal relationship between antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal disorders was assessed by a two-sample MR analysis dealing with exposure and outcome data. Three core assumptions were met: (1) IVs and exposure (antidiabetic drugs) are strongly correlated; (2) there is no correlation between IVs and confounders; and (3) there is no direct correlation between IVs and outcomes, and their effect on outcomes can only be reflected by the degree of exposure

Data source

Aggregate data for all genome-wide association studies (GWAS) used in the study were obtained from the IEU Open GWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets) [30] and are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the GWAS included in this MR study

| Trait | Dataset | Sample size | Number of SNPs | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | ||||

| Blood glucose | ebi-a-GCST90025986 | 400,458 | 4,218,897 | European |

| Outcome | ||||

| GERD | ebi-a-GCST90000514 | 602,604 | 2,320,781 | European |

| gastric ulcer | ebi-a-GCST90018851 | 474,278 | 24,178,780 | European |

| Chronic gastritis | ukb-b-6716 | 463,010 | 9,851,867 | European |

| Acute gastritis | finn-b-K11_ACUTGASTR | NA | 16,380,389 | European |

| Helicobacter pylori | ukb-b-531 | 462,933 | 9,851,867 | European |

| GC | ebi-a-GCST90018849 | 476,116 | 24,188,662 | European |

| FD | finn-b-K11_FUNCDYSP | 189,695 | 16,380,380 | European |

| IBS | ukb-b-2592 | 462,933 | 9,851,867 | European |

| UC | ukb-b-7584 | 462,933 | 9,851,867 | European |

| CD | ukb-a-552 | 337,199 | 10,894,596 | European |

| Diverticulosis | finn-b-K11_DIVERTIC | 182,423 | 16,380,412 | European |

| CRC | ieu-b-4965 | 377,673 | 11,738,639 | European |

| Positive control outcomes | ||||

| Diabetes | ukb-b-12,948 | 462,933 | 9,851,867 | European |

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; GU: Stomach ulcers; GC: Gastric cancer; FD: functional dyspepsia; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s Disease; CRC: Colorectal cancer; MR: Mendelian randomization; GWAS: Genome-wide association studies; SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms

Genetic instrumentation for antidiabetic drugs

We used the DrugBank (go.drugbank.com) and ChEMBL (ebi.ac.uk/chembl) databases to identify genes encoding the target proteins of these antidiabetic drugs [31, 32] (Table 2). Based on previous studies [33], we selected genome-wide salient variants (p < 5 × 10− 8) associated with blood glucose levels and SNPs within a 100 kb window of the target gene for each drug to determine exposure to antidiabetic drugs [34]. The instrumental variant SNPs were located within ± 100 kb of the antidiabetic drug site, ensuring that the linkage imbalance was not too strong (r2 < 0.3). We estimated the F-statistic of the instrument, retaining only SNPs with an F > 10 to avoid weak instrument bias [35]Since antidiabetic drugs are used to treat diabetes, we used diabetes as a positive control [36], utilizing GWAS pooled data that included 462,933 samples.

Table 2.

Target genes of antidiabetic drugs from DrugBank and ChEMBL databases

| Drug class | Encoding genes of target proteins | Gene location | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank | ChEMBL | ||

| Metformin | PRKAB1 | Fifty-eight encoding genes | (NA) |

| ETFDH | GPD2 | ||

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | GLP1R | GLP1R | Chr6: 39,016,557 − 39,059,079 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | SLC5A2 | SLC5A2 | Chr16: 31,494,323 − 31,502,181 |

| DDP-4 inhibitors | DPP4 | DPP4 | Chr2: 162,848,755 −162,930,904 |

| Insulin and its analogues | INSR | INSR | Chr19: 7,112,266-7,294,425 |

| Thiazolidinediones | PPARG | PPARG | Chr3: 12,328,867 − 12,475,855 |

| Sulfonylureas | KCNJ11 | KCNJ11 | Chr11: 17,386,719 − 17,410,878 |

| ABCC8 | ABCC8 | Chr11: 17,414,045 − 17,498,441 | |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors | M6PR | M6PR | Chr17:78,075,380− 78,093,680 |

GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1; SGLT2: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2; DPP4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4; NA: not applicable

Statistical analysis

We used MR analysis to align drug-targeted instrumental variables with outcome datasets. The inverse variance weighting (IVW) method was employed as the primary analytical method, disregarding the intercept term and using the reciprocal of the outcome variance (se squared) as a fitting weight [37]. The weighted median, MR-Egger regression, simple mode, and weighted mode were used as supplementary analysis methods to further improve the credibility and accuracy of the results [38]. To avoid heterogeneity in instrumental variables (IVs), we used Cochran’s Q test, where p > 0.05 indicated no significant heterogeneity [39]. The IVW method requires careful consideration of IVs to ensure their non-pleiotropic nature, as biased results may arise otherwise. Pleiotropy was assessed using MR-Egger regression to ensure that IVs did not introduce bias through alternative pathways. MR-Egger regression incorporates an intercept term and uses the inverse of the outcome variance (se squared) as a weighting factor for fitting. If the MR-Egger intercept is close to 0 or p > 0.05, it indicates no evidence of pleiotropic effects in IVs [40]. The “leave-one-out” method was used to systematically eliminate each SNP, calculate the meta-effect of the remaining SNPs, and assess whether there were any alterations in the results upon removal of each individual SNP. This approach aimed to mitigate potential influences from specific SNPs on our findings [41].

All analyses were performed using the “Two Sample MR” package [42] in R version 4.3.1. The threshold of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Selection and validation of genetic instruments

A total of 400,458 samples were included in the aggregated data of blood glucose GWAS. Through a rigorous selection process, no suitable genetic instruments were found for drugs such as metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, DDP-4 inhibitors, Insulin and its analogs, Thiazolidinediones, Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, etc. However, two SNPs were identified for GLP-1 receptor agonists, with one having an F-value of 11.5 after excluding those with F < 10. For sulfonylureas, three SNPs were identified with F-values of 11.4, 14.4, and 36.6, respectively. The F-values of these SNPs are all above the threshold of 10, indicating that our study largely avoids weak instrument bias.

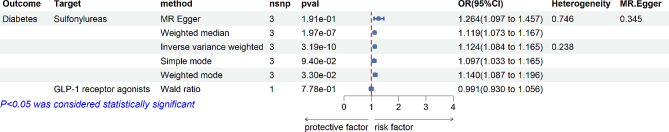

Positive control analysis

The pharmacogenetic analysis of antidiabetic drugs and diabetes mellitus showed positive results for sulfonylureas (IVW: OR [95% CI] = 1.12 [1.07–1.17], p = 1.97E-07). In contrast, the analysis for GLP-1 receptor agonists was negative (IVW: OR [95% CI] = 0.99 [0.93–1.06], p = 0.78) (Fig. 2). These positive control analyses validated the genetic instruments for sulfonylureas but not for GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists, sulfonylureas and diabetes mellitus

nsnp (number of single nucleotide polymorphisms), OR (odds ratio), CI (confidence interval)

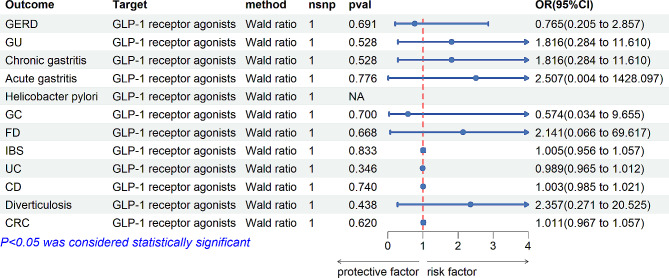

MR analysis of drug targets in gastrointestinal diseases

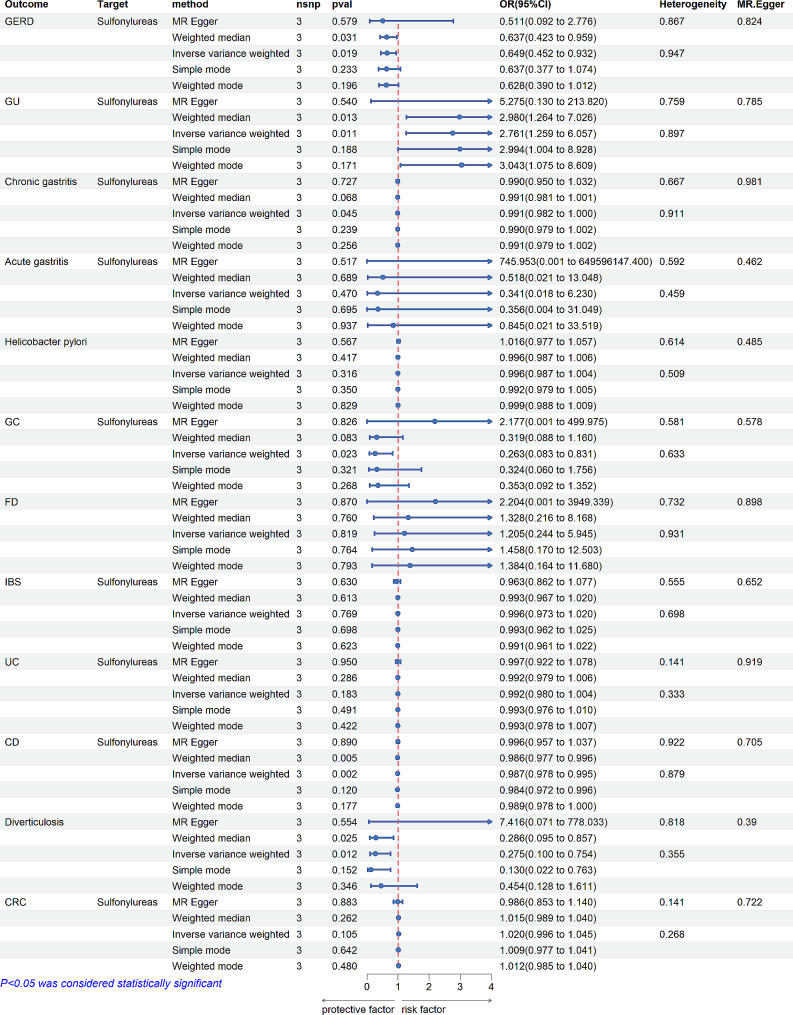

Drug-target MR Analysis was conducted to explore the causal relationship between antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal disorders. Genetic proxies for GLP-1 receptor agonists did not show a causal association with gastrointestinal disorders (Fig. 3). However, sulfonylureas were found to reduce the risk of CD (IVW: OR [95%CI] = 0.986 [0.978, 0.995], p = 1.99 × 10− 3; Weighted median: OR [95%CI] = 0.986 [0.977, 0.996], p = 5.30 × 10− 3), GERD (IVW: OR [95%CI] = 0.649 [0.452, 0.932], p = 1.90 × 10− 2; Weighted median: OR [95%CI] = 0.472 [0.242, 0.922], p = 2.78 × 10− 2), and chronic gastritis (IVW: OR[95%CI] = 0.991 [0.982, 0.999], p = 4.50 × 10− 2). Conversely, sulfonylureas increased the incidence of GU in patients with diabetes (IVW: OR [95%CI] = 2.761 [1.259, 6.057], p = 1,12 × 10 − 2; Weighted median: OR [95%CI] = 2.980 [1.264, 7.026], p = 1.26 × 10− 2) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists and gastrointestinal disorders

nsnp (number of single nucleotide polymorphisms), OR (odds ratio), CI (confidence interval), GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease;; GC: Gastric cancer; functional dyspepsia (FD); IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s Disease; CRC: Colorectal cancer

Fig. 4.

The relationship between Sulfonylureas and gastrointestinal disorders

nsnp (number of single nucleotide polymorphisms), OR (odds ratio), CI (confidence interval), GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; GC: Gastric cancer; functional dyspepsia (FD); IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s Disease; CRC: Colorectal cancer

Sensitivity analysis

Cochran’s Q-test showed no evidence of heterogeneity (p > 0.05). The MR-Egger intercept analysis indicated no horizontal pleiotropy (p > 0.05). The robustness of our conclusions was further supported by the leave-one-out sensitivity (Fig. 4). Thus, our MR analysis proved to be reliable and robust.

Discussion

We conducted large-scale MR analyses on gastrointestinal diseases using data from the IEU Open GWAS database. Our study investigated the causal relationship of seven common antidiabetic drug targets–metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, insulin and its analogs, thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors–on various gastrointestinal diseases. These diseases included GERD, GU, chronic gastritis, acute gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric cancer, FD, IBS, UC, CD, diverticulosis, and CRC. Our MR results showed that SGLT2 inhibitors, DDP-4 inhibitors, Insulin and its analogs, Thiazolidinedione, and other drugs did not have significant effects on gastrointestinal diseases and were not further analyzed. GLP-1 receptor agonists did not affect gastrointestinal tract diseases. Notably, sulfonylureas were found to reduce the risk of CD, GERD, and chronic gastritis but increase the risk of developing stomach ulcers.

The mechanisms underlying the preventive effects of sulfonylureas on the development of CD, GERD, chronic gastritis, and increased risk of GU remain unexplored. However, examining the pathways through which diabetes causes gastrointestinal diseases and reviewing clinical studies on sulfonylureas provide some insights.

Previous retrospective studies have indicated that gastrointestinal disorders are common complications of diabetes [43, 44]. MR studies have demonstrated an elevated risk of GERD [45] and gastritis [13] in individuals with diabetes. An MR study conducted by Xiang Xiao et al. revealed that type 2 diabetes reduces the risk of inflammatory bowel disease [46]. The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal complications in diabetes has been extensively explored in numerous articles.

Studies have shown that people with diabetes are more likely to develop GERD [45]. Animal studies have identified glucose-responsive neurons in the central nervous system, suggesting that high blood glucose may alter vagal efferent activity [47]. Clinical studies have shown that diabetes mellitus leads to dysfunction of the parasympathetic component of the autonomic nervous system, resulting in esophageal innervation dysfunction and gastroesophageal reflux disease [48, 49]. Sulfonylureas can reduce the incidence of GERD by modulating Drp-1-mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis, which ameliorates peripheral neuropathy [50, 51]. Crohn’s disease is a recurrent systemic inflammatory disease primarily involving the gastrointestinal tract, with extraintestinal manifestations and associated immune disorders [52, 53]. Studies have shown that mast cells release biologically active mediators such as serine proteases mMCP-6 and Prss31, which are involved in the development of acute colitis [54]. Animal experiments by Vijay Chidrawar et al. have shown that sulfonylureas can ameliorate inflammation by blocking cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance modulator channels on mast cells [55]. Chronic gastritis is an inflammatory disease of the gastric mucosa [56]. P Kashyap et al. demonstrated that oxidative stress plays a crucial role in diabetes mellitus, triggering gastrointestinal complications [39]. Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms [40]. Experiments in diabetic rats showed that sulfonylureas have significant antioxidant effects and can be used to treat Crohn’s disease and chronic gastritis by attenuating oxidative stress-induced damage. In addition, abnormal NLRP3 inflammasome activity has been identified as a key factor in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and chronic gastritis [57, 58]. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome by sulfonylureas can effectively inhibit the release of major proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines, which can effectively treat Crohn’s disease and chronic gastritis [58, 59].

The main factors leading to gastric ulcers include the presence of strong acids and high levels of proteolytic activity (pepsin) in gastric secretions [60]. Control tests by H.A.F Ismail et al. demonstrated that nicorandil could provide gastric protection by opening K (ATP) channels, scavenging free radicals, reducing pepsin and gastric acid secretion, and preventing harmful elevation of nitric oxide during water immersion-restraint stress [61]. However, sulfonylureas reduce blood glucose by inhibiting potassium flux in the ATP-dependent potassium channel (KATP) and inducing glucose-independent insulin release from β-cells [62]. As K (ATP) channel blockers [63], sulfonylureas can negate the protective effects of opening these channels, thereby increasing the risk of stomach ulcers.

Furthermore, a comparative study showed that hypoglycemia is associated with increased total pepsin secretion [64]. Sulfonylureas stimulate insulin release from pancreatic cells and have an extrapancreatic hypoglycemic effect, making them more likely to induce hypoglycemia [65]. The most common side effect of sulfonylureas is hypoglycemia [66]. Hence, one of the mechanisms by which sulfonylureas increase the risk of gastric ulcer may be attributed to their side effect of causing hypoglycemia, which subsequently leads to increased pepsin secretion and eventually gastric ulcer.

We employed MR studies to establish causal associations between sulfonylureas and CD, GERD, chronic gastritis, and GU. (1) Our MR study utilized genetic variants as proxies for antidiabetic drugs to mitigate confounding factors and reverse causality issues that may have affected previous studies. (2) Our analysis focused on individuals of European ancestry for both exposure and individual outcome data in order to effectively minimize potential association effects arising from population stratification. (3) In our study design, we selected genetic variants within a 100 kb window of the coding gene using a threshold of 5 × 10− 8 as instrumental variables. Additionally, we filtered out instrumental variables with an F value of less than 10 to improve the reliability of our results. (4) To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted positive control analysis, heterogeneity tests, pleiotropy tests, and sensitivity analyses throughout our study process. These measures further enhance the reliability of our results.

However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations in our study. Firstly, the TSMR analysis was solely based on individuals of European ancestry, which restricts generalizability beyond this specific population group. Caution should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to racially and ethnically diverse populations. Secondly, drug target MR can assess long-term drug effects but cannot replace clinical trials for verifying short-term drug effects. MR provides a way to analyze the causal relationship between exposure and outcome but cannot replace clinical trials. Also, our study did not investigate the association between other antidiabetic drugs and gastrointestinal diseases. Lastly, we used GWAS summary data from the IEU Open GWAS database. The data sources were not stratified, so further stratified analysis could not be performed.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that sulfonylureas may prevent CD, GERD, and chronic gastritis while increasing the risk of GU. These findings could help diabetic patients in managing and preventing certain gastrointestinal diseases. Further clinical trials are necessary to elucidate the potential mechanistic pathways between sulfonylureas and these conditions. Additionally, promoting better use of antidiabetic drugs is essential.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Leave one method for analysis chart. A: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: GERD; B: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: GU; C: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Chronic gastritis; D: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Acute gastritis; E: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: GC; F: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: IBS; G: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: UC; H: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: CD; I: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: CRC; J: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Diabetes; K: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Helicobacter pylori; L: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: FD); M: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: diverticulosis

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the IEU Open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/) for providing the site summary data on the outcome of this study, which has been instrumental in its inception.

Abbreviations

- IVs

Instrumental variables

- TSMR

Two-sample Mendelian randomization

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- IVW

Inverse variance weighted

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GU

Gastric ulcer

- GC

Gastric cancer

- FD

Functional dyspepsia

- IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MJ. Formal analysis: XJ. Investigation: MG, YL. Methodology: TD, XJ. Writing–original draft: MJ. Writing–review & editing: MJ. Supervision: FL, YY. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shandong Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Program (202204070951) and the Shandong Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (No.2021M175). Our funding status does not affect the results of the study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics Statement

The summary data we have utilized in our analysis are sourced from publicly accessible websites.The study did not involve any human or animal experiments, observations, or interventions.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors Mingyan Ju, Tingting Deng, Xuemin Jia, Menglin Gong, Yuying Li, Fanjie Liu, Ying Yi confirm that that they have no affiliations or memberships in any consortium or organization with financial interests pertaining to the subject matter of this article. Thus, there are no commercial or financial conflicts of interest involved.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fanjie Liu, Email: liufj198211@126.com.

Ying Yin, Email: 563298098@qq.com.

References

- 1.O’Morain N, O’Morain C. The burden of digestive disease across Europe: facts and policies. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldacre MJ. Demography of aging and the epidemiology of gastrointestinal disorders in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:793–804. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan B, Babu S, Walker J, Walker AB, Pappachan JM. Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2013;4:51–63. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v4.i3.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Pitchumoni CS, Chandrarana K, Shah N. Increased prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux diseases in type 2 diabetics with neuropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:709–12. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuschillo G, Celentano V, Rottoli M, Sciaudone G, Gravina AG, Pellegrino R, Marfella R, Romano M, Selvaggi F, Pellino G. Influence of diabetes mellitus on inflammatory bowel disease course and treatment outcomes. A systematic review with meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:580–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2022.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toh B-H. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:459–62. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bener A, Micallef R, Afifi M, Derbala M, Al-Mulla HM, Usmani MA. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter pylori infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2007;18:225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devrajani BR, Shah SZA, Soomro AA, Devrajani T. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection: a hospital based case-control study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2010;30:22–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.60008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo J, Liu C, Pan J, Yang J. Relationship between diabetes and risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;187:109866. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng C-H. Diabetes conveys a higher risk of gastric cancer mortality despite an age-standardised decreasing trend in the general population in Taiwan. Gut. 2011;60:774–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng C-H. Diabetes, insulin use, and gastric cancer: a population-based analysis of the Taiwanese. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:e60–64. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31827245eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng C-H. Diabetes but not insulin is associated with higher colon cancer mortality. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4182–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Yuan S, Fu T, et al. Gastrointestinal consequences of type 2 diabetes Mellitus and impaired glycemic homeostasis: a mendelian randomization study. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:828–35. doi: 10.2337/dc22-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolêto IRSG, Iles B, Alencar MS, et al. Alendronate-induced gastric damage in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic rats is reversed by metformin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;856:172410. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanchaitanawong W, Thinrungroj N, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N, Shinlapawittayatorn K. Repurposing metformin as a potential treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from cell to the clinic. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;112:109230. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tseng C-H. Metformin Use is Associated with a lower risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:64–73. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng C-H. Metformin reduces the risk of diverticula of intestine in Taiwanese patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:739141. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.739141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng C-H. Metformin reduces gastric cancer risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging. 2016;8:1636–49. doi: 10.18632/aging.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tseng C-H. Metformin is associated with a lower risk of colorectal cancer in Taiwanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:438–45. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng C-H. Diabetes, metformin use, and colon cancer: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:409–16. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tseng C-H. Metformin and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:e42–3. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tseng C-H. Diabetes, insulin use and Helicobacter pylori eradication: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulskas A, Patasius A, Kaceniene A, Linkeviciute-Ulinskiene D, Zabuliene L, Smailyte G. A cohort study of antihyperglycemic medication exposure and gastric Cancer risk. J Clin Med. 2020;9:435. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valent F. Diabetes mellitus and cancer of the digestive organs: an Italian population-based cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:1056–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sekula P, Del Greco MF, Pattaro C, Köttgen A. Mendelian randomization as an Approach to assess causality using Observational Data. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3253–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker VM, Davey Smith G, Davies NM, Martin RM. Mendelian randomization: a novel approach for the prediction of adverse drug events and drug repurposing opportunities. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:2078–89. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin C, Diaz-Gallo L-M, Tang B, Wang Y, Nguyen T-D, Harder A, Lu Y, Padyukov L, Askling J, Hägg S. Repurposing antidiabetic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: results from a two-sample mendelian randomization study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2023;38:809–19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-023-01000-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhury A, Duvoor C, Reddy Dendi VS, et al. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: implications for type 2 diabetes Mellitus Management. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:6. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 9. Pharmacologic approaches to Glycemic Treatment: standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S125–43. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Liu S, Wang Y, Wang Y. Causal relationship between particulate matter 2.5 and hypothyroidism: a two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1000103. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaulton A, Hersey A, Nowotka M, et al. The ChEMBL database in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D945–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo J, Liu R, Sheng F, Wu Q, Xu R, He H, Zhang G, Huang J, Zhang Z, Zhang R. Association between antihypertensive drugs and oral cancer: a drug target mendelian randomization study. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1294297. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1294297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang Z, Zhang Z, Tan X, Zeng P. Lipids, cholesterols, statins and liver cancer: a mendelian randomization study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1251873. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1251873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess S, Thompson SG, CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration Avoiding bias from weak instruments in mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–64. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowarah J, Singh VP. Anti-diabetic drugs recent approaches and advancements. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020;28:115263. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.115263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–65. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu S, Zhang L, Ma F, Xue S, Sun T, Xu Z. Effects of Selenium on chronic kidney disease: a mendelian randomization study. Nutrients. 2022;14:4458. doi: 10.3390/nu14214458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Zhao Q, Lawlor DA, Sheehan NA, Thompson J, Davey Smith G. Improving the accuracy of two-sample summary-data mendelian randomization: moving beyond the NOME assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:728–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:377–89. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee YH, Song GG. Uric acid level, gout and bone mineral density: a mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2019;49:e13156. doi: 10.1111/eci.13156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.H G, Z J, E B, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife. 2018 doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Careyva B, Stello B. Diabetes Mellitus: management of gastrointestinal complications. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:980–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zawada AE, Moszak M, Skrzypczak D, Grzymisławski M. Gastrointestinal complications in patients with diabetes mellitus. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27:567–72. doi: 10.17219/acem/67961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan S, Larsson SC. Adiposity, diabetes, lifestyle factors and risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a mendelian randomization study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022;37:747–54. doi: 10.1007/s10654-022-00842-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao X, Wu X, Yi L, You F, Li X, Xiao C. Causal linkage between type 2 diabetes mellitus and inflammatory bowel disease: an integrated mendelian randomization study and bioinformatics analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024;15:1275699. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1275699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizuno Y, Oomura Y. Glucose responding neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat: in vitro study. Brain Res. 1984;307:109–16. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hollis JB, Castell DO, Braddom RL. Esophageal function in diabetes mellitus and its relation to peripheral neuropathy. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:1098–102. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(19)31865-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syrine G, Mariem MK, Hend K, Imed L. Relationship between esophageal motility disorders and Autonomic Nervous System in Diabetic patients: Pilot North African Study. Am J Mens Health. 2022;16:15579883221098588. doi: 10.1177/15579883221098588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu Y, Shi L, Wu Y, Xu W, Wang L, Ren M. Protective effect of gliclazide on diabetic peripheral neuropathy through Drp-1 mediated-oxidative stress and apoptosis. Neurosci Lett. 2012;523:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao H, Feng J, Zheng Q, Wei Y, Wang S, Feng W. The effects of gliclazide, methylcobalamin, and gliclazide + methylcobalamin combination therapy on diabetic peripheral neuropathy in rats. Life Sci. 2016;161:60–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel J-F, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boeckxstaens G. Mast cells and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;25:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chidrawar V, Alsuwayt B. Defining the role of CFTR channel blocker and ClC-2 activator in DNBS induced gastrointestinal inflammation. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rugge M, Genta RM. Staging and grading of chronic gastritis. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chukwunonso Obi B, Chinwuba Okoye T, Okpashi VE, Nonye Igwe C, Olisah Alumanah E. (2016) Comparative Study of the Antioxidant Effects of Metformin, Glibenclamide, and Repaglinide in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rats. J Diabetes Res 2016:1635361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Yu Q, Shi H, Ding Z, Wang Z, Yao H, Lin R. The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM31 attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis by regulating ROS and autophagy. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:1. doi: 10.1186/s12964-022-00954-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Investigating regulatory patterns of NLRP. 3 Inflammasome features and association with immune microenvironment in Crohn’s disease - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36685554/. Accessed 16 May 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Tytgat GNJ. Etiopathogenetic principles and peptic ulcer disease classification. Dig Dis. 2011;29:454–8. doi: 10.1159/000331520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ismail Ha, Khalifa F, Hassan MMA, Ashour MK. Investigation of the mechanisms underlying the gastroprotective effect of nicorandil. Pharmacology. 2007;79:76–85. doi: 10.1159/000097817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thulé PM, Umpierrez G. Sulfonylureas: a new look at old therapy. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:473. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomai F, Crea F, Gaspardone A, Versaci F, De Paulis R, Penta de Peppo A, Chiariello L, Gioffrè PA. Ischemic preconditioning during coronary angioplasty is prevented by glibenclamide, a selective ATP-sensitive K + channel blocker. Circulation. 1994;90:700–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.2.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roberts NB, Sheers R, Taylor WH. Secretion of total pepsin and pepsin 1 in healthy volunteers in response to pentagastrin and to insulin-induced hypoglycaemia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:555–61. doi: 10.1080/00365520601010131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jennings PE, Scott NA, Saniabadi AR, Belch JJ. Effects of gliclazide on platelet reactivity and free radicals in type II diabetic patients: clinical assessment. Metabolism. 1992;41:36–9. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90093-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sola D, Rossi L, Schianca GPC, Maffioli P, Bigliocca M, Mella R, Corlianò F, Fra GP, Bartoli E, Derosa G. Sulfonylureas and their use in clinical practice. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:840–8. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.53304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Leave one method for analysis chart. A: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: GERD; B: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: GU; C: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Chronic gastritis; D: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Acute gastritis; E: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: GC; F: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: IBS; G: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: UC; H: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: CD; I: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: CRC; J: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Diabetes; K: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: Helicobacter pylori; L: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: FD); M: Exposure: Sulfonylureas, outcome: diverticulosis

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.