A central aim in establishing the NHS was to integrate primary care and health and social services in health centres. But this aim was compromised by the absence of public capital and the reluctance of the Treasury to buy out practice premises owned by general practitioners. Although there was some grant funding for health and local authority owned health centres, by 1974 only 15% of general practitioners operated out of these.1 General practitioner owned practice premises remained the dominant model from 1966 until 1989, financed by government loans and funded from NHS revenue under the rental reimbursement schemes. The privatisation of the government loan body in 1989 saw a switch to private finance and the entry of commercial companies and for-profit corporations. The amount of capital that can be raised by the private sector for new investment in the NHS is unrestricted. However, these debts have to be repaid through NHS funds or user charges.

The renewed impetus for integrated services in the 1997 white paper, The New NHS,2 means that more sophisticated buildings are required to accommodate advanced clinical technology and information systems. The complex financing and funding arrangements, combined with demographic factors, makes it likely that as general practitioners opt for a salaried service, the trend to for-profit corporations owning and buying out practice premises will accelerate.

Summary points

Healthcare companies and property developers are rapidly expanding into the ownership and provision of primary care premises

Under the private finance initiative, there are no restrictions on the amounts that can be borrowed or invested

“Bundling” of diverse NHS and non-NHS facilities into one project allows the commercial sector to target new sources of revenue

No data are collected centrally on the different types of public-private partnerships in primary care or on the various methods of financing and their implications for future NHS expenditure

Questions about the extent to which planning, population needs, and accountability are incorporated into the procurement process remain unanswered

Currently, primary care services are provided by 29 987 general practitioners in 9000 main surgeries and 2500 branch surgeries.3 The most recent survey of ownership carried out by the NHS Executive's valuation office in 1995-6 showed that 63% of practice premises were owned by general practitioners, 16% were owned by the NHS, and 21% were rented from the private sector.4 In its first capital investment strategy for the NHS, the Department of Health proposed a “national target of improving 1000 GP premises over the next 3 years [by] replicating the success of big hospitals in non-acute settings and to explore the scope for PFI [Private Finance Initiative] type solutions in primary care.”5 Recent estimates suggest that about £10bn needs to be invested in primary care over the next decade.6 Investment has started and is accelerating under the government's public-private partnerships initiative.

Although loans for practice premises are now increasingly from the commercial sector (see background paper on the BMJ's website), few data are collected centrally on the different types of public-private partnerships in primary care, their financing, and the implications for NHS expenditure. This article describes the new forms of ownership that are emerging in NHS primary care services.

Methods

We did a comprehensive review of business market surveys, the commercial press, and companies' annual reports, supplemented by telephone interviews and written correspondence with managers of companies and primary care leaders in health authorities and regions. We have divided market entrants into two main categories: healthcare companies and property developers, with several subclassifications.

Healthcare companies

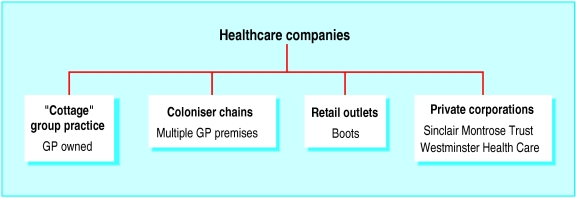

We have defined healthcare companies as those that have a primary interest in providing or supplying primary care services but that have diversified into premises and property ownership to gain access to NHS revenues. The spectrum of healthcare companies ranges from general practitioners in traditional group practice premises to major corporations (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Types and examples of healthcare companies investing in practice premises

Traditional “cottage” group practices

General practitioners may form limited companies to procure group practice premises. The Shadwell Medical Centre development in Leeds resulted from four general practitioners moving to larger premises to cope with an expanded list size. The doctors formed a separate property owning partnership and took out a £300 000 commercial loan. The expanded list size allowed the practice to take on another partner. The shortfall in income from NHS general medical services was made up by leasing space to a pharmacist and optician and office space to Leeds Community Mental Health Trust.4

Coloniser chains

Some general practitioners have moved from group to chain ownership of practice premises. The Cheltenham Family Healthcare Centre, which opened in April 1999, houses five practices and 26 general practitioners together with practice nurses, reception staff, and midwives. It serves 46 000 patients. The project cost £5.8m, including value added tax, land purchase, and rolled-up interest. Capital was provided by the General Practice Finance Corporation in the form of a 25 year repayment loan, and the health authority gave an £843 000 grant to fund space for non-general medical services. The doctors formed a limited company to buy the premises from the developers and to rent space. Three quarters of the rent comes from the NHS notional rent scheme for providing general medical services; the rest is paid from commercial sources, including a commercial lease negotiated with the local hospital for children's dental services.7

Some former fundholding practices have entered into joint venture with specialist companies such as Primary Medical Properties to provide commercial health, NHS, and care services (see below).

Retail outlets

Mainstream retail companies, including Boots and Superdrug, are also making forays into primary healthcare provision. Boots has incorporated the Medicentre branded surgeries into several shops. Medicentres are an American concept and provide private walk-in general practitioner clinics in supermarkets and train stations. The concept forms the basis of NHS walk-in centres.8 In March 2000 Birmingham's NHS walk-in centre was opened in Boots' city centre store. It is situated in the former Medicentre building, which the NHS leases from Boots. A team of 11 nurses supported by healthcare assistants and voluntary sector advisers provides advice on minor illnesses, basic blood pressure and urine testing, and health information.9

Boots is positioning itself to take a greater share of NHS business, taking it “one step closer to the development of a one-stop primary healthcare shop.”10 As well as offering travel and healthcare insurance, it has introduced in-store podiatry services and launched six dental practices in 1999 offering NHS dentistry.10 Other initiatives include free eye tests for elderly people.

Private healthcare companies

Sinclair Montrose is a major healthcare services group involved in hospital development and healthcare services in Europe and the United States. Its subsidiary, GP Deputising Service, provides clinical and administrative services. Since 1992, a subsidiary called Cost Rent Management has offered general practitioners and health authorities a property consultancy service for developing premises. It provides architectural design, project management, engineering, and valuation services in exchange for a consultancy fee from the health authority. However, in response to the shift towards much larger premises, for which general practitioners are increasingly unable and unwilling to take on the financial commitment required, the company set up the Healthcare Property Company in 1996. This company finances and owns property and leases it back to general practitioners. To date, it has provided 22 primary care premises in partnership with Cost Rent Management, which oversees the work (Sinclair Montrose, personal communication).

Westminster Healthcare is currently the third largest nursing and residential care provider in the United Kingdom. It provides services for older people and people with learning disabilities, medium secure units for mentally ill offenders, and diagnostic radiology services. Its current focus is on developing and expanding the government's new intermediate care sector. Westminster Healthcare was bought out last April by a company headed by Dr Chai Patel,11 who is part of the government's NHS regulation taskforce and highly influential in health policy. Westminster Healthcare offers several integrated healthcare packages in primary care centres, subacute hospitals, intermediate care, and town hospitals for populations of 50 000-100 000. Its stated aim is to “bring together private sector expertise in business management and finance with those professionals responsible for the delivery of care on the ground” (letter to Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham Health Authority, 23 August, 1994). Some general practitioners are now operating out of the company's private hospitals or renting space for NHS care.

Property companies

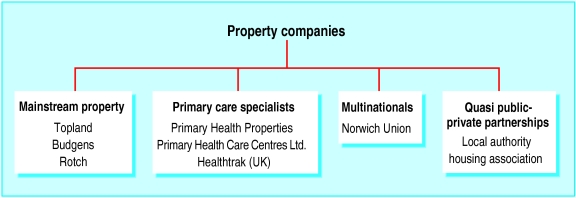

We have defined property companies as having a primary interest in property investment but increasingly diversifying into both non-clinical and clinical operations (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Types and examples of property companies investing in practice premises

Mainstream property companies

In January 2000, the Sunday Times reported that Topland was planning to become the country's biggest owner of doctors' surgeries. The company's owners, the Zakay brothers, have set aside £100m of their family fortune to invest in the sector. Topland plans to buy the surgeries and lease them back to general practitioners at agreed rents, which will then effectively be underwritten by the government.

Topland has modelled its business on Rotch, a larger private property company, which is currently involved in several private finance initiative and public-private partnership projects in the health sector.12 These include complex “bundling” of community hospital and mental health facilities—such as the Queen Mary's Sidcup NHS Trusts, Oxleas NHS Trust, and Sedgefield Community Hospital.13 Recently, however, the NHS has abandoned four private finance initiative health deals in the south east of England with consortiums led by Rotch because they were unable to show value for money.14

Companies specialising in primary care premises

More than a dozen companies specialising in primary care premises have emerged in the past three to five years. We have identified eight market leaders engaged in more than 300 projects (table). These include Primary Health Properties, Primary Health Care Centres, the GP Investment Corporation, and Primary Medical Properties. Some are subsidiaries of larger groups. The investment and development company Primary Medical Properties is an operating division of building contractor Morgan Sindall, which provides working capital and management support. The GP Investment Corporation is part of the GP Group, a holding company for various investments in property, transport, and healthcare. Others, such as Primary Health Care Centres, are freestanding concerns. Primary Health Properties, although nominally an individual company owned by shareholders, has its portfolio managed by Nexus Management Services, part of the larger Nexus group. Nexus is a financial advisory company that has undertaken over 100 healthcare projects with the NHS in the past few years, ranging from workforce planning to major capital developments. It is currently establishing partnership arrangements with several primary care groups and trusts. Companies are increasingly diversifying into clinical services.

Healthtrak (UK), which is run by Bradford general practitioner Mendhy Khan, is unusual in that it provides external maintenance of properties. It also offers up to £20 000 per partner as an incentive to exchange premises for a leasehold. The one-off payments are met from the company's 15-20% profit margins, which are built into project costs. Dr Khan expects such “offers” to be common in the next few years.15

Multinational health concerns

Norwich Union, together with the specialist property and finance company Mill Group, has committed £200m for private finance initiatives and public-private partnership investments in small to medium sized (£10m-£50m) projects in health, education, and social care.16 The Norwich Union partnership currently has two primary care projects. Bradford Community Trust has signed a deal for £4m on behalf of the Horton Park Medical Centre in West Yorkshire. It includes three general practices, a pharmacy, an optician, a restaurant, and a welfare benefits office. The Sedgley Community Health Centre in the West Midlands is a £3.5m joint venture with health and local authorities to provide purpose built integrated care facilities for use by social workers, visiting nurses, and a general practitioner out of hours service. It will also provide dental and family planning services, a library, a base for the local mental health team, and offices for Age Concern and the Citizens' Advice Bureau. Additional benefits for Norwich Union include access to patients and doctors for marketing their private healthcare and health insurance products.17 Norwich Union owns the General Practice Finance Corporation, formerly a Treasury owned public loan body (see BMJ's website).

Quasi-private groups or partnerships

Voluntary and not-for-profit bodies are also involved in partnerships. Housing associations are diversifying into care in the community programmes and working with community and mental health NHS trusts to build or operate group homes for NHS clients. Presentation Housing Association and Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham Health Authority built a new surgery alongside 12 general needs flats at a cost of £861 000. The housing association raised £722 500 by private finance, and the shortfall was provided by the health authority from London Initiative Zone funds—that is, by a direct subsidy.

Discussion

The rapidly expanding market in primary care premises is accompanied by increasingly complex arrangements for their financing and funding. The switch to private finance has relaxed capital constraints imposed through government borrowing, and market entrants face no restrictions on the amounts they can borrow or on the nature and scale of investment.18

The Treasury task force, which oversees public-private partnerships, has been split into two government agencies: the Office of Government Commerce develops policy on public-private partnerships, and Partnerships UK is responsible for its implementation. Partnerships UK has launched a new venture equity arm (Local Improvement Finance Trust) for investment in primary care premises. It is also promoting and facilitating project bundling, where groups of NHS premises and other non-NHS facilities, such as benefits offices, social services, housing, and commercial and retail outlets, are combined to form a single capital project. Project bundling is presented by government as a means of integrating services, but its aim is to provide the commercial sector with the means of generating new sources of revenue or income to underpin capital investment.

Income for investors comes from a combination of state and commercial sources. There is the money formerly paid under the NHS cost rent scheme to general practitioners, as well as NHS payments for providing community services and intermediate and acute care. Local authorities' revenues may pay for social services, housing, libraries, and benefits offices. Finally, there are commercial revenues from charging users of private healthcare premises such as nursing homes and from renting housing or retail outlets.

The strategy for new investment, which focuses on maximising the investment opportunity of the commercial sector, raises questions about the appropriateness of arrangements for provision and planning of NHS and social care facilities. In some of the schemes, project bundling seems to decrease access to care and services, contrary to the government's stated aim of “bringing services closer to home.” There is little or no publicly available information on how the planning is done and what the implications of such schemes are for accessibility and use of services, or for the overall levels of affordability.

These increasingly complex arrangements also raise questions about risk if some or all parts of the venture fail. If retail and commercial outlets cannot provide the income required, will revenue be diverted from NHS and local authority services to service debts and meet the private finance initiative or public-private partnership payments, as currently happens in private finance initiative hospitals?19–21 This will be at the expense of patient care.

As we have shown, the development of infrastructure is often the first stage in gaining access to NHS revenues and NHS patients. The ultimate prize for the private sector is to obtain a much greater share of NHS revenue spent on patient care by providing clinical services. The Health and Social Care Bill, which will implement the “concordat” with the private sector, will make it easier for private sector companies to operate former NHS facilities and clinical services and take over the clinical workforce. It remains to be seen whether the government can safeguard the goals and principles of the NHS when healthcare is provided on a purely commercial basis.

Supplementary Material

Table.

Some of new companies involved in primary care since 1995

| Company | No of premises completed or under negotiation |

|---|---|

| Primary Medical Properties | 80 |

| Sinclair Montrose Trust | 67 |

| Primary Health Properties | 50 |

| Primary Health Care Centres | 49 |

| Healthtrak (UK) | 49 |

| GP Investment Corporation | 34 |

| Primary Medical Facilities | 25 |

| Nestor Health Group | 25 |

Source: Interviews with managers in companies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

An article giving more background to this paper is available on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Rivett G. From cradle to grave. London: King's Fund; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Secretary of State for Health. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1997. . (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. Statistics for general medical practitioners in England: 1989-1999. Statistical Bulletin 2000/8.

- 4.Bailey J, Glendinning C, Gould H. Better buildings for better services: innovative developments in primary care. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. The government's expenditure plans 1999-2000. London: Stationery Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes S, Owens D. Primary care groups: opportunities for investment. PFI Report 1998 October:10-1.

- 7.Wild S. Create a perfect practice. Medeconomics 1999 Mar:56-62.

- 8.Crail M. Shutting up shop. Health Service Journal 1999 July 29:14-5.

- 9.Department of Health. NHS walk-in centres, West Midlands. www.doh.gov.uk/nhswalkincentres/westmidlands.htm (accessed 10 Apr 2001).

- 10.Bawden T. The world at your feet. Design Week 1999 Mar19:8.

- 11.Laing and Buisson. Community Care Market News 1999 Apr:1-2.

- 12.Waples J. Zakay brothers to buy up surgeries. Sunday Times 2000 January 2.

- 13.Bundled mental health deal signed. PFI Report 1999 Jul/Aug:2-3.

- 14.Stewart T. Risking failure. PFI Report 2000 Nov:24-5.

- 15.Slingsby C. Leaving your mortgage for a new lease of life. Medeconomics 2000 May:78-81.

- 16.The directory. PFI Report 2000 Sept:36.

- 17.Pollock AM, Godden S, Player S. GPs' surgeries turn a profit. Public Finance 1999 Dec 2:26-8.

- 18.Persaud J. GPs get help on cost rent. Medeconomics. 1997 Dec:21.

- 19.Gaffrey D, Pollock AM. Pump priming the private finance initiative: why are privately financed hospital schemes being subsidized? Public Money Manag. 1999;19:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollock AM, Dunnigan M, Gaffrey D, Price O, Shaoul J. Planning the “new” NHS: downsizing for the 21st century. BMJ. 1999;319:179–184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaffrey D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. PFI in the NHS—is there an economic case? BMJ. 1999;319:116–119. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7202.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.