The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) develops evidence based clinical guidelines for the NHS in Scotland. The key elements of the methodology are (a) that guidelines are developed by multidisciplinary groups; (b) they are based on a systematic review of the scientific evidence; and (c) recommendations are explicitly linked to the supporting evidence and graded according to the strength of that evidence.

Until recently, the system for grading guideline recommendations was based on the work of the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research).1,2 However, experience over more than five years of guideline development led to a growing awareness of this system's weaknesses. Firstly, the grading system was designed largely for application to questions of effectiveness, where randomised controlled trials are accepted as the most robust study design with the least risk of bias in the results. However, in many areas of medical practice randomised trials may not be practical or ethical to undertake; and for many questions other types of study design may provide the best evidence. Secondly, guideline development groups often fail to take adequate account of the methodological quality of individual studies and the overall picture presented by a body of evidence rather than individual studies or they fail to apply sufficient judgment to the overall strength of the evidence base and its applicability to the target population of the guideline. Thirdly, guideline users are often not clear about the implications of the grading system. They misinterpret the grade of recommendation as relating to its importance, rather than to the strength of the supporting evidence, and may therefore fail to give due weight to low grade recommendations.

Summary points

A revised system of determining levels of evidence and grades of recommendation for evidence based clinical guidelines has been developed

Levels of evidence are based on study design and the methodological quality of individual studies

All studies related to a specific question are summarised in an evidence table

Guideline developers must make a considered judgment about the generalisability, applicability, consistency, and clinical impact of the evidence to create a clear link between the evidence and recommendation

Grades of recommendation are based on the strength of supporting evidence, taking into account its overall level and the considered judgment of the guideline developers

In 1998, SIGN undertook to review and, where appropriate, to refine the system for evaluating guideline evidence and grading recommendations. The review had three main objectives. Firstly, the group aimed to develop a system that would maintain the link between the strength of the available evidence and the grade of the recommendation, while allowing recommendations to be based on the best available evidence and be weighted accordingly. Secondly, it planned to ensure that the grading system incorporated formal assessment of the methodological quality, quantity, consistency, and applicability of the evidence base. Thirdly, the group hoped to present the grading system in a clear and unambiguous way that would allow guideline developers and users to understand the link between the strength of the evidence and the grade of recommendation.

Methods

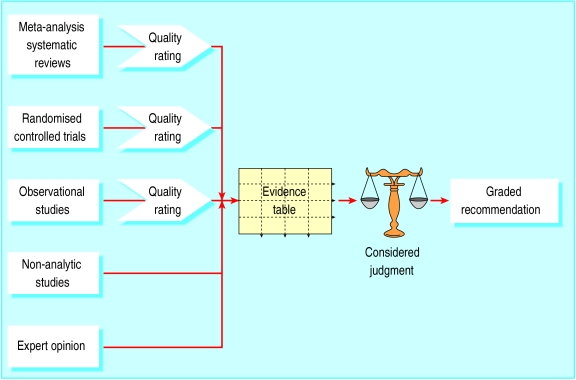

The review group decided that a more explicit and structured approach (figure) to the process of developing recommendations was required to address the weaknesses identified in the existing grading system. The four key stages in the process identified by the group are shown in the box.

The strength of the evidence provided by an individual study depends on the ability of the study design to minimise the possibility of bias and to maximise attribution. The hierarchy of study types adopted by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research is widely accepted as reliable in this regard and is given in box B1.1

Box 1.

Hierarchy of study types

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials

- Randomised controlled trials

- Non-randomised intervention studies

- Observational studies

- Non-experimental studies

- Expert opinion

The strength of evidence provided by a study is also influenced by how well the study was designed and carried out. Failure to give due attention to key aspects of study methods increases the risk of bias or confounding and thus reduces the study's reliability.3 The critical appraisal of the evidence base undertaken for SIGN guidelines therefore focuses on those aspects of study design which research has shown to have a significant influence on the validity of the results and conclusions. These key questions differ between types of studies, and the use of checklists is recommended to ensure that all relevant aspects are considered and that a consistent approach is used in the methodological assessment of the evidence.

We carried out an extensive search to identify existing checklists. These were then reviewed in order to identify a validated model on which SIGN checklists could be based. The checklists developed by the New South Wales Department of Health were selected because of the rigorous development and validation procedures they had undergone.4 These checklists were further evaluated and adapted by the grading review group in order to meet SIGN's requirements for a balance between methodological rigour and practicality of use. New checklists were developed for systematic reviews, randomised trials, and cohort and case control studies, and these were tested with a number of SIGN development groups to ensure that the wording was clear and the checklists produced consistent results. As a result of these tests, some of the wording of the checklists was amended to improve clarity.

A supplementary checklist covers issues specific to the evaluation of diagnostic tests. This was based on the New South Wales checklist,4 adapted with reference to the work of the Cochrane Methods Working Group on Systematic Review of Screening and Diagnostic Tests and Carruthers et al.5,6

The checklists use written responses to the individual questions, with users then assigning studies an overall rating according to specified criteria (see box B24). The full set of checklists and detailed notes on their use are available from SIGN.7

Box 2.

Key stages in developing recommendations

- Methodological evaluation—Using defined criteria, evaluate the methodological quality of the evidence base for the guideline and give each study a quality rating according to a standard scale (below). The study type combined with the assessment of methodological quality determines the level of evidence

- Synthesis of evidence—Compile an evidence table of studies of an acceptable standard identified as relevant to each of the key clinical questions addressed by the guideline

- Considered judgment—Make a considered judgment about the relevance and applicability of the evidence to the target patient group for the guideline, the consistency of the evidence base, and the likely clinical impact of the intervention

- Grading system—Assign a grading to the recommendation according to the strength of the evidence base and the degree of extrapolation required to form the recommendation

- Quality rating for individual studies (adapted from Liddle et al4)

- ++ Applies if all or most criteria from the checklist are fulfilled; where criteria are not fulfilled, the conclusions of the study or review are thought very unlikely to alter.

- + Applies if some of the criteria from the checklist are fulfilled; where criteria are not fulfilled or are not adequately described, the conclusions of the study or review are thought unlikely to alter.

- − Applies if few or no criteria from the checklist are fulfilled; where criteria are not fulfilled or are not adequately described, the conclusions of the study or review are thought likely or very likely to alter.

Synthesis of the evidence

The next step is to extract the relevant data from each study that was rated as having a low or moderate risk of bias and to compile a summary of the individual studies and the overall direction of the evidence. A single, well conducted, systematic review or a very large randomised trial with clear outcomes could support a recommendation independently. Smaller, less well conducted studies require a body of evidence displaying a degree of consistency to support a recommendation. In these circumstances an evidence table presenting summaries of all the relevant studies should be compiled.

Considered judgment

Having completed a rigorous and objective synthesis of the evidence base, the guideline development group must then make what is essentially a subjective judgment on the recommendations—one that can validly be made on the basis of this evidence. This requires the exercise of judgment based on clinical experience as well as knowledge of the evidence and the methods used to generate it. Although it is not practical to lay out “rules” for exercising judgment, guideline development groups are asked to consider the evidence in terms of quantity, quality, and consistency; applicability; generalisability; and clinical impact.

Increasing the role of subjective judgment in this way risks the reintroduction of bias into the process. It must be emphasised that this is not the judgment of an individual but of a carefully composed multidisciplinary group. An additional safeguard is the requirement for the guideline development group to present clearly the evidence on which the recommendation is based, making the link between evidence and recommendation explicit and explaining how they interpreted that evidence.

Grading system

The revised grading system (box B3) is intended to strike an appropriate balance between incorporating the complexity of type and quality of the evidence and maintaining clarity for guideline users. The key changes from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research system are that the study type and quality rating are combined in the evidence level; the grading of recommendations extrapolated from the available evidence is clarified; and the grades of recommendation are extended from three to four categories, effectively by splitting the previous grade B which was seen as covering too broad a range of evidence type and quality.

Box 3.

Revised grading system for recommendations in evidence based guidelines

- Levels of evidence

- 1++ High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias

- 1+ Well conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias

- 1− Meta-analyses, systematic reviews or RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias

- 2++ High quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies or

- High quality case-control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding, bias, or chance and a high probability that the relationship is causal

- 2+ Well conducted case-control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding, bias, or chance and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal

- 2− Case-control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding, bias, or chance and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal

- 3 Non-analytic studies, eg case reports, case series

- 4 Expert opinion

- Grades of recommendations

- A At least one meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT rated as 1++ and directly applicable to the target population or

- A systematic review of RCTs or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+ directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results

- B A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++ directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results or

- Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+

- C A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+ directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results or

- Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++

- D Evidence level 3 or 4 or

- Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+

System in practice

Inevitably, some compromises had to be made, and for some areas of practice, such as diagnosis, recommendations higher than grade B are unlikely because of the type of study that can feasibly be conducted in those areas. However, the review group expects that grade A recommendations will become relatively rare under the new system, and that grade B will come to be regarded as the best achievable in many areas. Early results from applying this system in practice suggest that this expectation is well founded. Further research will be required to establish the extent to which this new system meets the objectives set for it.

Figure.

Overview of the process for developing and grading guideline recommendations

Footnotes

Funding: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma. Rockville, MD: AHCPR; 1993. p. 107. . (Clinical practice guideline No 1, AHCPR publication No 92-0023.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadorn DC, Baker D, Hodges JS, Hicks N. Rating the quality of evidence for clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:749–754. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elwood JM. Critical appraisal of epidemiological studies and clinical trials. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liddle J, Williamson M, Irwig L. Method for evaluating research and guideline evidence (MERGE). Sydney: New South Wales Department of Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cochrane Methods Working Group on Systematic Review of Screening and Diagnostic Tests. Recommended methods. Updated 6 June 1996. www.cochrane.org/cochrane/sadtdoc1.htm (accessed 22 March 2001).

- 6.Carruthers SG, Laroche P, Haynes RB, Petrasovits A, Schiffrin EL. Report of the Canadian Hypertension Society consensus conference. I: introduction. Clinical practice guidelines. Can Med Assoc J. 1993;149:289–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50: a guideline developers' handbook. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2001. [Google Scholar]