Highlights

-

•

CD276 (B7-H3) gene expression is associated with BCG unresponseviness in NMIBC patients.

-

•

IDO1 expression is a marker of worse prognosis in NMIBC.

-

•

MSI and PD-L1 expressions are not associated with responsiveness of BCG vaccine in NMIBC patients.

Keywords: Urinary bladder neoplasms1, BCG vaccine 2, Gene expression profiling3, Immunity active4

Abstract

Methods

One-hundred-six patients diagnosed with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and treated with intravesical BCG were included and divided into two groups, BCG-responsive (n = 47) and -unresponsive (n = 59). Immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate PD-L1 expression and MSI was assessed by a commercial multiplex PCR kit. The mRNA expression profile of 15 immune checkpoints was performed using the nCounter technology. For in silico validation, two distinct cohorts sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database were used.

Results

Among the 106 patients, only one (<1 %) exhibited MSI instability. PD-L1 expression was present in 9.4 % of cases, and no association was found with BCG-responsive status. We found low gene expression of canonic actionable immune checkpoints PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), and CTLA4, while high expression was observed for CD276 (B7-H3), CD47, TNFRSF14, IDO1 and PVR (CD155) genes. High IDO1 expression levels was associated with worst overall survival. The PDCD1, CTLA4 and TNFRSF14 expression levels were associated with BCG responsiveness, whereas TIGIT and CD276 were associated with unresponsiveness. Finally, CD276 was validated in silico cohorts.

Conclusion

In NMIBC, MSI is rare and PD-L1 expression is present in a small subset of cases. Expression levels of PDCD1, CTLA4, TNFRSF14, TIGIT and CD276 could constitute predictive biomarkers of BCG responsiveness.

Introduction

Bladder carcinoma is a common malignancy of the urinary tract and accounts for approximately 2.1 % of cancer-related deaths globally [1]. It is the tenth most common type of cancer worldwide, with urothelial carcinoma being the predominant type, representing almost 90 % of all diagnoses [2]. The incidence rate of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), such as stage Ta, T1 stages and carcinoma in situ (CIS), is nearly 75 % and based on their individual risk of progression, patients are stratified as having low, intermediate, high, or very high risk, which is crucial for recommending adjuvant treatment [3,4]. The standard treatment for high-risk NMIBC patients, such as high-grade Ta, carcinoma in situ, or any T1, involves transurethral resection of the bladder tumor followed by intravesical full-dose of bacillus Calmette-Gérin (BCG) vaccine for 1–3 years [5]. This treatment method initially exhibits high efficacy, with complete response rates reaching 75 % [6]. The antitumor effect of BCG vaccine is mediated through activation of the immune system and subsequent inflammatory response and requires a competent host immune system. However, the precise mechanism underlying tumor immunity remains unclear [7].

Nevertheless, nearly half of high-risk NMIBC patients treated with BCG vaccine will experience disease recurrence within five years, and to establish clear definitions for clinical trials, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has created criteria for BCG-unresponsive patients [8]. These include those with recurrent or persistent CIS or high-grade Ta/T1 tumors after adequate BCG vaccine, as well as those with initial clearance of NMIBC after BCG therapy but subsequent recurrence within 6 months (for high-grade Ta/T1 tumors) or 12 months (for CIS) of the last dose of BCG vaccine. BCG-unresponsive patients have a high risk of progression, with a 20–40 % risk of developing muscle-invasive bladder cancer within five years, carrying a 50 % chance of developing incurable metastatic disease [9]. In cases of BCG-unresponsiveness, NMIBC patients undergo radical cystectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection and urinary diversion which is a major surgery associated with high morbidity and mortality rates and might negatively impact the patient's quality of life [9,10].

Currently, immune checkpoint therapies, such as PD-1/PD-L1 therapies, have been established for the treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. Those tumors also exhibit high microsatellite instability (MSI-H), a predictive biomarker for those therapies [15,16]. Pembrolizumab has been approved as a treatment option for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with in situ characteristics,[17] even without a predictive response biomarker [18,19]. However, there are several other non-canonic immune checkpoints unexplored, their knowledge in bladder cancer is still limited, and they might represent risk-stratified biomarkers or even new and promising targets for therapy [20,21]. Understanding the environment of the BCG-unresponsive patients and characterizing the immune checkpoint expression profile in NMIBC is crucial for the development of effective and appropriate immune checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy.

The present study aims to assess the expression profile of 15 immune checkpoints, PD-L1 expression and MSI status in BCG-treated non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and associate these markers with BCG response as well as performing in silico validation.

Material and methods

Study population

We included 106 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) NMIBC specimens from patients at high risk of progression and recurrence,[5] diagnosed at Barretos Cancer Hospital (BCH), Barretos, Brazil, from 2003 to 2018. The histology was reviewed by experienced pathologists. All patients underwent BCG vaccine treatment in adherence with the institution's protocol, which aligns with international guidelines. The protocol involved a 6-weekly induction phase followed by a 3-weekly installation schedule, repeated every 6 months for a total of 3 years for maintenance [22]. The patients were categorized again into two distinct groups: BCG-unresponsive and BCG-responsive, in accordance with the criteria outlined by the FDA guideline [8]. Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at Barretos’ Cancer Hospital (Project #1248/2016).

DNA and RNA isolation

From the FFPE samples, the tumor area was initially delineated to ensure that more than 60 % of the sample contained tumor cells, a task carried out by a proficient pathologist. Following this step, both DNA and RNA were extracted from the FFPE samples. For DNA extraction, the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) was utilized, and the quantification of DNA was performed using the NanoDroPVR 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham) as previously reported [23]. Meanwhile, RNA isolation and quantification were done using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) and NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham), respectively [24].

Microsatellite instability status

The Human Target – Microsatellite Instability Plus (HT-MSI+) kit from Cellco (São Carlos, Brazil) was used to conduct MSI analysis. The kit includes a multiplex PCR which involves the use of six quasi-monomorphic mononucleotide repeat markers, namely BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, NR-27, and HSP110. The assay was carried out with 0.5 μL of DNA that was present in 50 ng/mL concentration. The reverse primers used were end-labeled with fluorescent dyes. Quasimonomorphic variation range (QMVR) was established for each marker based on allele size that fell within a range of plus or minus three nucleotides [25,26].

PD-L1 immunohistochemistry and score

All 106 cases were analyzed for PD-L1 expression using the PD-L1 clone E1L3N antibody (XP® Rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling Technology) by immunohistochemistry. The samples were processed by deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval using Dako EnVision FLEX Target Retrieval pH6. The staining was performed using the Dako Automated Link 48, and the PD-L1 antibody was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and previous studies[27,28] with human mature placenta used as a positive control. The slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin. To be considered positive, neoplastic cells had to exhibit partial or complete membrane staining, while any staining level was counted for immune cells. A minimum of 100 neoplastic cells were evaluated to determine the validity of the sample.

We used three scores for PD-L1 immunohistochemistry classification: Tumor Proportion Score (TPS), Immune Cell Score (IC Score), and Combined Positive Score (CPS). The TPS represents the percentage of the area covered by tumor cells that are positive for PD-L1 (in any intensity), divided by the total tumor area, and multiplied by 100 %. The IC Score considered the percentage of the area occupied by immune cells that are positive for PD-L1 (lymphocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages, and granulocytes) relative to the entire tumor area, multiplied by 100 %. The CPS is the sum of the number of PD-L1-positive tumor cells and PD-L1-positive immune cells, relative to the total number of vital tumor cells, and then multiplied by 100. The CPS is reported without any units, and although theoretically, it can exceed 100, the highest possible score is set at 100. Additionally, TPS, IC Score, and CPS are categorized as either negative (<1 % for TPS and IC Score, and <1 for CPS) or positive (≥ 1 % for TPS and IC Score, and ≥1 for CPS) [29,28].

Immune checkpoint expression analysis

The gene expression of 15 immune checkpoint genes was performed in the nCounter® FLEX Analysis System, using the PanCancer IO 360 Panel (NanoString Technologies, Inc., Seattle, WA). This panel comprises 730 immuno-oncology-related targets, including 109 cell surface markers for 14 immune cell types and 40 reference genes. The normalization of the data was performed in R v.4.0 statistical environment. Messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) level below 20 counts was considered background.

For downstream analysis, we selected 15 immune checkpoints described in the literature: PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), CTLA4, CD276 (B7-H3), LAG3, PVR (CD155), CD47, CD80, CD86, IDO1, HAVCR2 (TIM-3), CD48, TNFRSF14, CD244 and TIGIT. [24,30,31].

To make comparisons between different subgroups of NMIBC, we started by evaluating the normality of the expression data of each immune checkpoint-related gene. When normality was established, the statistical test performed was the Independent Samples T-test, whilst the opposite was observed, we performed a non-parametric approach with the Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U Test. We considered genes differentially expressed when the p-value was <0.05. The statistical tests were made in SPSS v27. The heatmap-scaled data was obtained using the R function scale, and the heatmap was generated using GraphPad 8. We obtained the median values of gene expression after normalization. Subsequently, we classified expression levels as low if they fell from the median and high if they exceeded the median.

In silico validation

To validate our findings, we downloaded gene expression data from two independent cohorts deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database: GSE154261,[32] which included 73 T1 high-grade NMIBC patients, and GSE19423,[33] with 48 pT1 bladder cancer cases, all treated with BCG. Twenty-three patients from the first cohort and 22 from the second cohort, who experienced relapse or progression after the treatment, were considered BCG-unresponsive.

We then analyzed the expression of significant genes identified in the discovery cohort alongside genes associated with specific cell types to gain mechanistic insights. Graphical representations were generated using the ggplot2 package in the R v4.2.0 programming environment [34].

Statistical analysis

We evaluated overall survival using the Kaplan-Meier method and determined the p-value using the log-rank test. Patients without any events related to overall survival were censored at the date of their last known visit at which they were still alive.

Results

Patients characterization

The median follow-up of the 106 patients was 4.8 years (range 0.87 to 15.7 years). The clinical and pathological characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were male (71.1 %), had high tumor grade (80.2 %), and had T1 stage (78.3 %), with only three patients presenting with CIS. Of the total patients, 59 (55.7 %) were classified as BCG-unresponsive, and 47 (44.3 %) were classified as BCG-responsive. Regarding patient outcomes, 85 (80.2 %) were alive and 21 (19.8 %) had passed away (Table 1). Of the deceased patients, three were in the BCG-responsive group, while 18 patients were in the BCG-unresponsive group (p = 0.002). In 10 years, 84.7 % of BCG-responsive patients were alive, while 53,0 % of the BCG-unresposive patients were deceased. (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) cases treated with bacillus Calmette-Gérin (BCG).

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 106 |

| Age at diagnosis, years (y) | |

| Median | 69 |

| Range | 31 - 89 |

| ≤ 69 y | 52 (49.1 %) |

| > 69 y | 54 (50.9 %) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 76 (71.7 %) |

| Female | 30 (28.3 %) |

| Tumor grade | |

| Low | 19 (17.9 %) |

| High | 85 (80.2 %) |

| Not specified | 2 (1.9 %) |

| Tumor stage (T of AJCC) | |

| CIS | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Ta | 20 (18.9 %) |

| T1 | 83 (78.3 %) |

| BCG responsiveness | |

| Unresponsive | 59 (55.7 %) |

| Responsive | 47 (44.3 %) |

| Status | |

| Alive | 85 (80.2 %) |

| Deceased | 21 (19.8 %) |

CIS: carcinoma in situ; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

MSI analysis

Of the 105 cases analyzed (1 case was excluded due to insufficient material), only one patient exhibited MSI-H (Supplementary Fig. 2).

PD-L1 immunohistochemistry analysis

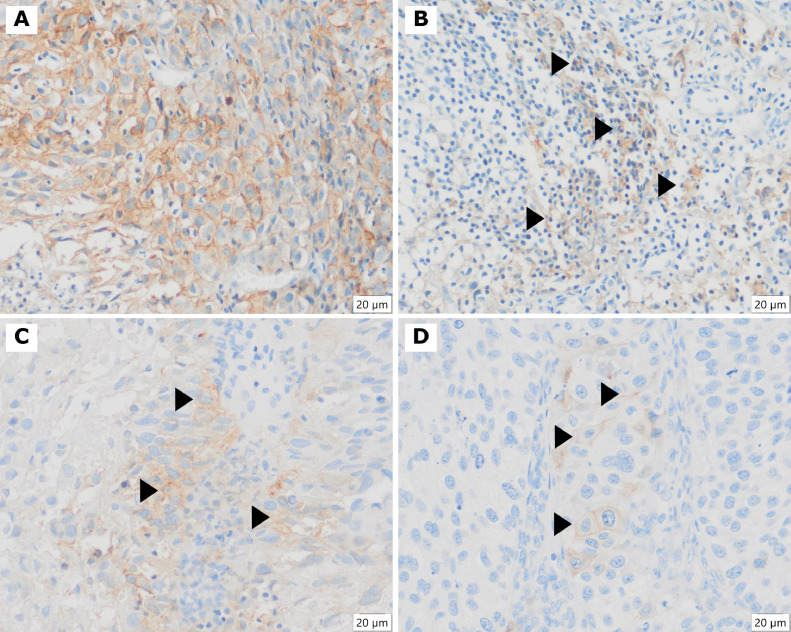

The immunohistochemistry evaluation was possible in all 106 cases (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Using TPS, none of the BCG-responsive patients depicted PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, whereas only 3 patients (5 %) in the BCG-unresponsive group expressed PD-L1 in tumor cells (Table 2). Using the IC Score, 17 patients showed PD-L1 expression, with 4 patients (9 %) in the BCG-responsive group and 13 patients (22 %) in the BCG-unresponsive group. Despite the tendency (p = 0.059), the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in CPS between the BCG-responsive and BCG-unresponsive groups (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Illustrative cases with positive PD-L1 immunoexpression. A and B are the same case. A) Large amount of tumor cells exhibiting membrane positivity (TPS ≥ 1 % - positive), 400X objective. B) Mononuclear cells, mainly lymphocytes (arrows), with membrane positivity, inflammatory cell score (IC Score ≥ 1 % - positive), 400X objective. C and D) Focal tumor cells revealing membrane positive expression (arrows) (both TPS ≥ 1 %), 400X objective. All cases are CPS ≥ 1 (positive).

Table 2.

PD-L1 expression of the of 106 non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) samples analysed.

| Classifier | n | BCG-responsive n (%) | BCG-unresponsive n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC score | ||||

| < 1 % | 89 | 43 (91 %) | 46 (78 %) | 0,059a |

| ≥ 1 % | 17 | 4 (9 %) | 13 (22 %) | |

| TPS | ||||

| < 1 % | 103 | 47 (100 %) | 56 (95 %) | 0,169b |

| ≥ 1 % | 3 | 0 | 3 (5 %) | |

| CPS | ||||

| < 1 | 96 | 44 (94) | 52 (88 %) | 0,507b |

| ≥ 1 | 10 | 3 (6) | 7 (12 %) |

IC: Immune cell; TPS: tumor proportion score; CPS: combined positive score;.

a: Chi-square test; b: Fisher's exact test.

Immune checkpoints gene expression profile

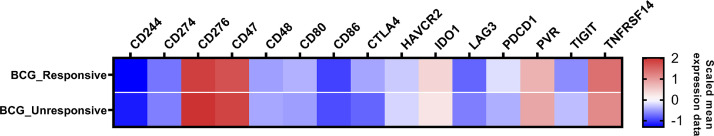

The mRNA analysis of immune checkpoints was reliable in all 106 NMIBC cases. The well-known actionable targets PDCD1, CD274, and CTLA4 showed low mRNA count levels (Fig. 2 and Table 3). The mRNA normalized counts for PDCD1 had a mean value of 14.7. Similarly, the mRNA mean levels of CTLA4 and CD274 were consistently below the background threshold of 20 counts. We observed that only five genes, namely CD276 (B7-H3), CD47, TNFRSF14, IDO1 and PVR, exhibited high mRNA count levels, while most of the other non-canonic immune-checkpoint genes showed low mRNA levels, indicating a lack of expression. Among the 5 genes, CD276 displayed the highest expression level (mean count = 190.2), followed by CD47 (mean count = 156.3), TNFRSF14 (mean count = 89.8), PVR (mean count = 54.5) and IDO1 (mean count = 47.0) (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Fig. 2.

mRNA expression heatmap of 15 immune checkpoint-related genes in the NMIBC cohort. The heatmap illustrates the mean normalized mRNA counts of the examined genes, using a color scale. Blue indicates counts below the background threshold, white signifies low counts (below 100), and red indicates higher counts. The heatmap was generated using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

Table 3.

The mRNA expressions levels of immune checkpoint genes in 106 NMIBC by BCG responsiveness groups.

| Genes | Total expression mean ± SD | BCG-responsive (n = 47) mean ± SD | BCG-unresponsive (n = 59) mean ± SD | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD244 | 5.79 ± 4.77 | 5.64 ± 5.65 | 5.91 ± 3.98 | 0.082a |

| CD274 (PD-L1) | 10.15 ± 7.60 | 9.91 ± 8.60 | 10.35 ± 6.76 | 0.469a |

| CD276 (B7-H3) | 190.42±72.54 | 171.13±66.64 | 205.79±73.91 | 0.013b |

| CD47 | 156.38 ± 64.81 | 139.44 ± 46.73 | 169.87 ± 73.85 | 0.070a |

| CD48 | 12.47 ± 7.71 | 11.84 ± 6.14 | 12.97 ± 8.79 | 0.539a |

| CD80 | 11.81 ± 4.84 | 12.64 ± 5.82 | 11.15 ± 3.82 | 0.208a |

| CD86 | 6.98 ± 2.72 | 6.81 ± 2.91 | 7.11 ± 2.58 | 0.769a |

| CTLA4 | 10.16±5.23 | 11.78±5.27 | 8.88±4.87 | 0.003a |

| HAVCR2 (TIM-3) | 15.38 ± 6.56 | 14.49 ± 6.64 | 16.08 ± 6.47 | 0.085a |

| IDO1 | 47.06 ± 90.91 | 57.75 ± 108.14 | 38.55 ± 74.31 | 0.772a |

| LAG3 | 9.36 ± 5.44 | 8.61 ± 5.34 | 9.96 ± 5.49 | 0.078a |

| PDCD1 (PD-1) | 14.70±8.31 | 17.19±10.23 | 12.72±5.74 | 0.011b |

| PVR (CD155) | 54.56 ± 33.04 | 47.89 ± 21.50 | 59.87 ± 39.30 | 0.112b |

| TIGIT | 12.82±7.36 | 10.82 ± 6.05 | 14.41±7.96 | 0.005b |

| TNFRSF14 | 89.88±46.71 | 101.67±47.83 | 80.49±43.96 | 0.012a |

NMIBC: non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; SD: standard deviation. Significante level at p < 0.05; a: Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U Test; b: Independent Samples T-Test.

We further evaluated the association of mRNA levels of CD274 and the protein expression of PD-L1 according to CPS by immunohistochemistry and found that high CD274 levels significantly associated with CPS positivity (p = 0.0088) (Fig. 3). We also evaluated the immune-checkpoint profile of the MSI patient, and no difference was observed when compared with the other unresponsive patients (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Association between the mRNA levels of CD274 (PD-L1) and immunohistochemistry expression of PD-L1 according to the Combined Positive Score (CPS). The x-axis represents the expression of PD-L1 according to CPS and the y-axis represents the mRNA expression of the CD274 gene assessed using NanoString. The significance level is p < 0.05.

Association of immune checkpoints gene expression profile and patients’ BCG response and clinical outcome

Next, we interrogated whether the expression profile of immune checkpoint gene levels is associated with BCG responsiveness (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Despite the low mRNA count levels observed, we found that higher mRNA levels of PDCD1 and CTLA4 were significantly associated with patient response to BCG (Fig. 4). Similarly, TNFRSF14 expression was significantly higher in the BCG-responsive group (mean count = 101.67) compared to the BCG-unresponsive group (mean count = 80.49). At variance, we observed that higher CD276 and TIGIT expression levels were significantly associated with BCG-unresponsiveness (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

mRNA levels for PDCD1 (PD-1), CTLA4, CD276 (B7-H3), TNFRSF14 and TIGIT across BCG-unresponsive and responsive groups of 106 NMIBC samples using the nCounter technology. The significance level is 0.05. * < 0.05; ** < 0.01.

Although CD47, IDO1, and PVR genes also exhibited high mRNA count levels, no statistically significant differences were found between the BCG-responsive and BCG-unresponsive groups (Table 3).

Finally, we evaluated the association of expression levels of the 15 genes with patients’ overall survival (Supplementary Table 1) and clinical-pathologic characteristcs (Supplementary Table 2).

We observed elevated levels of CD48 in female patients (p = 0.041). Additionally, increased levels of CD276 were correlated with higher tumor grade (p < 0.001). High TIGIT levels were further associated with more aggressive tumors, including T1 stage (p < 0.001) and high grade (p = 0.031), while low TIGIT levels were linked to a negative IC Score (p = 0.006). Furthermore, elevated levels of IDO1 were associated with poor overall survival. Specifically, over a 10-year period, 56.6 % of patients with high IDO1 levels were alive, compared to 74.1 % of patients with low IDO1 levels (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Association of immune regulatory cells gene expression and patients’ BCG response

We investigated the involvement of immune regulatory cells in BCG response by evaluating the expression of FOXP3, a marker of regulatory T cells (Tregs), and ITGAM, a marker of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), in tumor tissue samples and in silico. Our findings revealed elevated FOXP3 levels in BCG-unresponsive patients (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Tregs might be contributing to the observed immune suppression. ITGAM expression was not associated with BCG response (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Expression of immune regulatory markers in BCG-responsive and -unresponsive patients. A) Expression of FOXP3 (marker of regulatory T cells) in tumor tissue samples from patients who responded (in orange) and did not respond (in gray) to BCG therapy, for each cohort. B) Expression of ITGAM (marker of myeloid-derived suppressor cells) in tumor tissue samples from patients who responded (in orange) and did not respond (in gray) to BCG therapy, for each cohort. The significance level is 0.05. * < 0.05; ** < 0.01; *** < 0.001; ns: not significant.

In silico validation

The five differentially expressed genes between BCG-responsive and unresponsive in the discovery cohort (CD276, CTLA4, PDCD1, TIGIT and TNFRSF14) had expression data available in the validation cohorts and were further analyzed. When comparing patients based on their BCG response, the differential expression of CD276 was validated in both cohorts (p < 0.05), with its higher expression associated with no response (Fig. 6). No significant differences were observed in the expression of the other genes between groups (Supplementary Fig. 5)

Fig. 6.

CD276 expression levels comparing BCG-responsive and unresponsive patients from the discovery and validation cohorts. The significance level is 0.05. * < 0.05; ** < 0.01.

Discussion

In the present study, we performed for the first time, an expression characterization of 15 immune checkpoints, and associated them with BCG responsiveness in a series of 106 NMIBC and through in silico analysis. We also evaluated the profile of immunotherapy biomarkers PD-L1 expression and MSI. We found low mRNA counts for the canonic PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1) and CTLA4 immune checkpoints. Moreover, we also found an association between CD274 (PD-L1) mRNA and protein levels. Interestingly, NMIBC exhibited higher expression of non-canonic CD276 (B7-H3), CD47, TNFRSF14, IDO1 and PVR (CD155) immune checkpoints. Importantly, we found that PDCD1, CTLA4 and TNFRSF14 expression were associated with BCG responsiveness while CD276 and TIGIT to unresponsiveness.

MSI is a marker of genomic hypermutability and in urothelial carcinomas is estimated at around 1 % [35]. In accordance, we found only one patient (0.94 %) presenting MSI-H in our cohort. MSI is associated with mutational burden and consequent agnostic response to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) pembrolizumab [36]. Our MSI-positive patient was unresponsive to BCG, and its immune checkpoint profile was similar to the other patients unresponsive to BCG.

Using a cutoff of 1 in the CPS score, we found PD-L1 expression in 9.4 % of the cases, which was not significantly different among BCG-responsive or unresponsive patients. ICIs have been extensively explored in bladder cancer in the last decade either in muscle-invasive or NMIBC [18,37]. Despite international regulatory agencies requiring PD-L1 test for using first-line ICI in cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced bladder cancer, running PD-L1 test is not a current practice [38]. Furthermore, in the KEYNOTE 057 cohort A trial, Balar et al. used pembrolizumab to treat high-risk NMIBC BCG-unresponsive patients harboring CIS with or without papillary tumors [17]. The authors found CPS ≥ 10 in only 38 % of cases and the rate of complete response was even worse for this group (CPS < 10, 48.2 % versus CPS ≥ 10, 28.6 %).

Although MSI and PD-L1 have been considered as predictive biomarkers for ICI use in a few tumors, it seems not true for bladder cancer and other non-canonic players deserve to be explored in depth.

Our study evaluated a considerable number of NMIBC cases and strictly divided them into two groups according to the last well-accepted classification by the FDA. The two groups are representative of the studied population and well balanced. Moreover, we explored relevant immune checkpoint-associated genes using a new technology, paving the path for new hypothesis generation. TIGIT is an immunoreceptor inhibitor checkpoint that has been implicated in tumor immunosurveillance and have been identified on the surface of CD8+ T cells in bladder cancer, but their function has not been well characterized [39]. Although TIGIT has been associated with BCG-unresponsiveness in our cohort, its expression level was low and these finding was not corroborated by in silico analysis. The highest immune checkpoint expression observed in our study was CD276 (B7-H3) and was correlated with higher tumor grade. Additionally, CD276 (B7-H3) expression was significantly higher in the BCG-unresponsive group compared to the BCG-responsive group and also validated in silico analysis. CD276 (B7-H3) is a type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein that contains an extracellular domain and is expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), natural killer (NK) cells, B and T cells, endothelial cells (ECs), fibroblasts and tumor cells [18]. CD276 (B7-H3) overexpression has been described in some tumors and leads to aberrant angiogenesis to hamper intra-tumoral infiltration of CD8+ T cells [40]. Moreover, cancer stem cell in urothelial carcinoma is hypothesized to promote tumor escape from immune surveillance through CD276 (B7-H3) expression [41]. Additionally, CD276 (B7-H3) has been positively associated with the Treg density (FOXP3+ T cells) and in head and neck cancer a positive correlation with MDSCs has been also described [42]. We investigated, in our cohort and in silico, the involvement of immune regulatory cells in BCG response and our findings revealed an association of Treg's and BCG-unresponsiveness, suggesting that Tregs might be contributing to the observed immune suppression, despite we did find any association between MDSCs and BCG response.

Higher levels of CD276 (B7-H3) have been associated with poor prognosis and microRNAs (miR-29, miR-124, miR-128), immunoglobulin-like transcript (ILT) 4, autophagy and mTORC1 signatures have been implicated as CD276 (B7-H3) regulators [43]. In urothelial carcinoma, CD276 (B7-H3) expression is significantly elevated in all disease stages compared to normal tissue [44]. Moreover, low co-expression of CD276 (B7-H3) and PD-L1 has been described, corroborating with our findings where CD276 (B7-H3) expression was high while low mRNA count levels were seen for CD274 [40,45]. Mahamoud et al. studied muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients in chemotherapy adjuvant settings and described high CD276 (B7-H3) expression associated with decreased recurrence-free survival and cancer-specific survival [45]. In the NMIBC setting, Azuma et al. measured the serum B7-H3 (sB7-H3) level and found 47 % of patients with high levels of sB7-H3 in the sera in contrast to only 8 % in healthy donors [46]. The same authors also reported that sB7-H3 increase was significantly associated with poor relapsing and progression-free survival.

Intravesical BCG remains the mainstay treatment in high-risk NMIBC. Therefore, our findings suggest CD276 (B7-H3) as a potential target to reverse the BCG unresponsiveness. Of note, several anti-B7-H3 approaches have been explored using different effector mechanisms such as monoclonal antibodies, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), CAR-T therapy, and Antibody Drug Conjugate (ADC) [47,48]. Recently, Aggarwal et al. evaluated the role of enoblituzumab, an investigational anti-B7-H3 humanized monoclonal antibody, associated with anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab in solid tumors [49]. In this phase I/II study, the authors included 17 patients with advanced urothelial cancer previously treated with ICI and only one (1/17) partial response was described. Yet, no study addressed anti-B7-H3 in NMIBC. Furthermore, ifinatamab deruxtecan (Ds-7300a), a new ADC conjugating a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor and DXd-based antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD276 (B7-H3), has been explored in patients with solid tumors extensively pre-treated and it has been presented promising results in preliminary reports (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04145622) [50].

Furthermore, IDO1 presented high expression levels in our cohort and despite it has not been associated with BCG-responsiveness, elevated levels of IDO1 were associated with poor overall survival. IDO1 is an INF-γ-induced immunomodulating enzyme that has been linked to the cancer cell invasiveness and its expression seems to be changed during bladder carcinoma invasion in pre-clinical models [51]. Addiotionally, IDO1 seems to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition through PD-L1 pathway [52]. Zhang et al. evaluated the prognostic role of IDO1 expression in solid tumors through a systematic review and meta-analysis and they found shorter Overall Survival associated with high expression of IDO1, corroborating with our findings [53].

Despite our study observations, there are some limitations to be considered. It is a retrospective study from only one center and some selection bias should be expected. Another pertinent point is the FFPE sample from different years that might harbor a spectrum of immunogenicity influencing the PD-L1 staining.

Conclusion

In NMIBC, MSI is a rare event and PD-L1 expression is present in a small subset of cases. mRNA counts of canonic actionable immune checkpoints is low and, in case of CD274, it correlates to immunohistochemistry staining for PD-L1. CD276 is highly expressed and should be better explored as a potential BCG unresponsiveness biomarker. In the age of immune checkpoint therapies, new trials could be better designed in the of a better understanding of the expression and regulation of all immune checkpoints in the NMIBC microenvironment.

Data availability

The authors acknowledge that the data presented in this study must be deposited and made publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus data repository, prior to publication.

Funding

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – FAPESP (2019/23679–5) as a regular research grant and partially supported by the Public Ministry of Labor Campinas (Research, Prevention, and Education of Occupational Cancer—15ª zone, Campinas, Brazil). RMR was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil) with a Research Productivity Scholarship—Level 1B LERZ and FMC were supported by PAIP (Researcher Support Program) from Barretos Cancer Hospital.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Luis Eduardo Rosa Zucca: Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Ana Carolina Laus: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation. Bruna Pereira Sorroche: Formal analysis, Validation. Eduarda Paro: Data curation. Luciane Sussuchi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis. Rui Ferreira Marques: Validation, Formal analysis. Gustavo Ramos Teixeira: Validation, Formal analysis. Gustavo Noriz Berardinelli: Validation, Formal analysis. Lidia Maria Rebolho Batista Arantes: Writing – review & editing. Rui Manuel Reis: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Flavio Mavignier Cárcano: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our patients who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102003.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Saginala K., et al. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer. Medical sciences. 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/medsci8010015. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jubber I., et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer in 2023: a systematic review of risk factors. Eur. Urol. 2023;84:176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bladder cancer — cancer stat facts. Accessed in March 4th, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html.

- 4.Babjuk M., et al. European association of urology guidelines on non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Ta, T1, and carcinoma in situ) Eur. Urol. 2022;81:75–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oddens J., et al. Final results of an EORTC-GU cancers group randomized study of maintenance bacillus calmette-guérin in intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: one-third dose versus full dose and 1 year versus 3 years of maintenance. Eur. Urol. 2013;63:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales A., Eidinger D., Bruce A.W. Intracavitary Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of superficial bladder tumors. J. Urol. 1976;167 doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(02)80294-4. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen E.S., Joensen U.N., Poulsen A.M., Goletti D., Johansen I.S. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy for bladder cancer: a review of immunological aspects, clinical effects and BCG infections. APMIS. 2020;128 doi: 10.1111/apm.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDER & CBER. BCG-Unresponsive Nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: developing drugs and biologics for treatment (Draft) Guidance. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roumiguié M., et al. International bladder cancer group consensus statement on clinical trial design for patients with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin–exposed high-risk non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2022;82:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCCN Guidelines version 3.2021. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Bladder Cancer. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf.

- 11.Balar A.V., et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma: results from KEYNOTE-045 and KEYNOTE-052 after up to 5 years of follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023;34:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vuky J., et al. Long-term outcomes in KEYNOTE-052: phase II study investigating first-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:2658–2666. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grivas P., et al. Patient-reported outcomes from JAVELIN bladder 100: avelumab first-line maintenance plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone for advanced urothelial carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2023;83:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajorin D.F., et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus placebo in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:2102–2114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao P., Li L., Jiang X., Li Q. Mismatch repair deficiency/microsatellite instability-high as a predictor for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy efficacy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019;12 doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0738-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li K., Luo H., Huang L., Luo H., Zhu X. Microsatellite instability: a review of what the oncologist should know. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-1091-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balar A.V., et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for the treatment of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer unresponsive to BCG (KEYNOTE-057): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:919–930. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Beltran A., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of bladder cancer. Cancers. 2021;13:1–16. doi: 10.3390/cancers13010131. (Basel) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z., et al. Predictive biomarkers of response to bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy and bacillus Calmette-Guérin failure for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Int. J. Urol. 2022;29:807. doi: 10.1111/iju.14921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahmoud A.M., et al. Evaluation of PD-L1 and B7-H3 expression as a predictor of response to adjuvant chemotherapy in bladder cancer. BMC Urol. 2022;22:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12894-022-01044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attalla K., et al. TIM-3 and TIGIT are possible immune checkpoint targets in patients with bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2022;40:403. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Rhijn B.W.G., et al. Recurrence and progression of disease in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: from epidemiology to treatment strategy. Eur. Urol. 2009;56:430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cárcano F.M., et al. Absence of microsatellite instability and BRAF (V600E) mutation in testicular germ cell tumors. Andrology. 2016;4:866–872. doi: 10.1111/andr.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marques R.F., et al. Digital expression profile of immune checkpoint genes in medulloblastomas identifies CD24 and CD276 as putative immunotherapy targets. Front. Immunol. 2023;14:457. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1062856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berardinelli G.N., et al. Advantage of HSP110 (T17) marker inclusion for microsatellite instability (MSI) detection in colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9:28691–28701. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berardinelli G.N., et al. Association of microsatellite instability (MSI) status with the 5-year outcome and genetic ancestry in a large Brazilian cohort of colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;30:824–832. doi: 10.1038/s41431-022-01104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junior J.N.A., et al. PD-L1 expression and microsatellite instability (MSI) in cancer of unknown primary site. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024 doi: 10.1007/S10147-024-02494-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Marchi P., et al. PD-L1 expression by tumor proportion score (TPS) and combined positive score (CPS) are similar in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J. Clin. Pathol. 2021;74:735–740. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tretiakova M., et al. Concordance study of PD-L1 expression in primary and metastatic bladder carcinomas: comparison of four commonly used antibodies and RNA expression. Mod. Pathol. 2018;31:623–632. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He X., Xu C. Immune checkpoint signaling and cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pancancer IO 360 gene expression panel | nanostring technologies. 2024 Accessed in March 14, 2024. https://nanostring.com/products/ncounter-assays-panels/oncology/pancancer-io-360/.

- 32.Robertson A.G., et al. Identification of differential tumor subtypes of T1 bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2020;78:533–537. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim Y.J., et al. Gene signatures for the prediction of response to Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy in primary pT1 bladder cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2131–2137. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wickham H. Springer International Publishing; 2016. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics For Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandran E., et al. Mismatch repair deficiency and microsatellite instability-high in urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:4570. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.4570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim M.S., Prasad V. Pembrolizumab for all. J Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023;149:1357. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okobi T.J., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors as a treatment option for bladder cancer: current evidence. Cureus. 2023;15 doi: 10.7759/cureus.40031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eckstein M., et al. PD-L1 assessment in urothelial carcinoma: a practical approach. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019;7:690. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.10.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu K., et al. Targeting TIGIT inhibits bladder cancer metastasis through suppressing IL-32. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.801493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mortezaee K. B7-H3 immunoregulatory roles in cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023;163 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harland N., et al. Elevated expression of the immune checkpoint ligand CD276 (B7-H3) in urothelial carcinoma cell lines correlates negatively with the cell proliferation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23094969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mortezaee K. B7-H3 immunoregulatory roles in cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023;163 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H.J., et al. mTORC1 upregulates B7-H3/CD276 to inhibit antitumor T cells and drive tumor immune evasion. Nat. Commun. 2023;14 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36881-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aicher W.K., et al. Expression patterns of the immune checkpoint ligand CD276 in urothelial carcinoma. BMC Urol. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/s12894-021-00829-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahmoud A.M., et al. Evaluation of PD-L1 and B7-H3 expression as a predictor of response to adjuvant chemotherapy in bladder cancer. BMC Urol. 2022;22 doi: 10.1186/s12894-022-01044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azuma T., Sato Y., Ohno T., Azuma M., Kume H. Serum soluble B7-H3 is a prognostic marker for patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. PLoS One. 2020;15 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou W.T., Jin W.L. B7-H3/CD276: an emerging cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.701006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Getu A.A., et al. New frontiers in immune checkpoint B7-H3 (CD276) research and drug development. Mol. Cancer. 2023;22 doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01751-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aggarwal C., et al. Dual checkpoint targeting of B7-H3 and PD-1 with enoblituzumab and pembrolizumab in advanced solid tumors: interim results from a multicenter phase I/II trial. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2022;10 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma M.R., et al. 481P A phase I first-in-human study of XL092 in patients (pts) with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors: results from dose-escalation of XL092 alone and in combination with atezolizumab. Ann. Oncol. 2022;33:S760. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santos H.J.S.P., et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 expression is changed during bladder cancer cell invasion. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2022;15 doi: 10.1177/11786469211065612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W., et al. Overexpression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition by activation of the IL-6/STAT3/PD-L1 pathway in bladder cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2019;12:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H., Li J., Zhou Q. Prognostic role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 expression in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.954495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors acknowledge that the data presented in this study must be deposited and made publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus data repository, prior to publication.