An important obstacle to improving men's health is their apparent reluctance to consult a doctor. US research shows that men with health problems are more likely than women to have had no recent contact with a doctor regardless of income or ethnicity.1 This reluctance means that men often do not seek help until a disease has progressed.2 Late presentation can have serious consequences. For example, deaths from melanoma are 50% higher in men than women despite a 50% lower incidence of the disease. So why do men delay seeking help, and what can be done to overcome the problem?

Summary points

Men do care about health issues but often find it difficult to expresses their fears

Men tend to attend their general practitioner later in the course of a condition than women and this phenomenon is exacerbated by social class inequalities

Uptake of health information and health services can be improved by making them male friendly, anonymous, and more convenient

Better use should be made of services such as NHS Direct, pharmacists, occupational health, and online advice

The nature of medical school education and medical training may contribute to potential problems in consultations between male doctors and patients

What are the difficulties?

Suicide is now the single greatest cause of death among young men in most of the United Kingdom. One reason that more men die from suicide than women is that men are more likely to choose methods such as hanging or shooting that leave little room for medical intervention. Even so, men are less likely to talk about their problems with their peers or health professionals. Although the Samaritans claim that a large proportion of men have visited their general practitioner in the months before they take their own lives,3 a report by the Men's Health Forum concludes the opposite. A multidisciplinary approach is therefore more likely to reduce rates of male suicide. Suicide rates fell by around half after such an approach was introduced in Dorset.4

Men's knowledge of health matters is often poor. In a survey conducted by the Doctor Patient Partnership with the Men's Health Forum, 18% of men thought a GUM clinic dealt with dental problems, over 50% had no idea what a genitourinary clinic was, and most did not know which sexually transmitted diseases were becoming more common.

Lack of awareness may also contribute to late diagnosis. The effects of heart disease, the greatest cause of early male death, and type 2 diabetes, with which one million people remain undiagnosed,5 could be reduced if the conditions were detected earlier. The incidence of these diseases could also be reduced by better knowledge of risk factors such as male obesity.

MARK OLDROYD

Sources of knowledge and help

Gender is an important factor determining the source of health information used. Women are more likely to seek advice from peers, magazines, books, and the television than men. There are also differences in how men from different socioeconomic groups access and respond to information. Middle class men are more likely than working class men to access and respond to health promotion information from leaflets and advertising. Men tend not to rely on the experience of their peers, preferring to try to live life as normal.6 The macho male maxim of “strength in silence” has an important effect on their desire for information, particularly while they are being treated for a medical condition.

Health and the lack of it is perceived by many men from an early age to be the domain of women. Boys are more often brought to the child health surveillance clinics by female relatives than by male relatives. Pressure from parents and government for high academic standards force schools to give health and the use of health services a low priority. However, girls tend to pick up more information from other sources and are enabled to talk about it. There are numerous publications aimed at adolescent girls that deal with emotional and relationship issues, but there is no equivalent for boys until they reach the age range for men's magazines.

A study of young men's use of sexual health services found that the average young man is unlikely to access any help or support at all if he has a problem. Instead, he will manage on his own. In the words of one young man when asked where he would go for help, “the only safe place was in my head.”7

Attending a general practice surgery can be difficult for many men, and they often find it male unfriendly. There are few male receptionists or practice nurses, so the first point of contact may be off putting for men with an “embarrassing condition,” which may nonetheless be life threatening.8 Waiting rooms display all the propaganda of women's and children's health, but there are few if any examples for men. This could be due to the lack of any government initiative on general male health screening and the fact that virtually no health promotion literature is produced for men other than on sexual health.

Age can also be a factor. Younger men are aware of issues like healthy eating and the importance of fitness but other health issues can be seen as irrelevant. Young men may view attending the general practitioner as wimpish and consequently look down on those who bother the doctor with “minor” symptoms.

Problems in the consultation

Training in medical school has been described as sadomasochistic,9 and much of it is imbued with the macho male culture. The force feeding of coping, survival, omnipotence, leadership, and medical arrogance create a testosterone driven consultation guaranteed to prevaricate over male sexuality, embarrassment, and personal relationships. As if this were not bad enough, social class introduces its own complications for the consultation. The Office of National Statistics 2001 report on life expectancy inequalities pointed out a 10 year difference in life expectancy between men living in the north of the United Kingdom and those in the south. Part of the explanation for this is that although young men from the lower socioeconomic groups, which are assumed to be poor users, visit the doctor on average 2.21 times a year, they seem to be attending just for treatment and are missing out on preventive health care.10

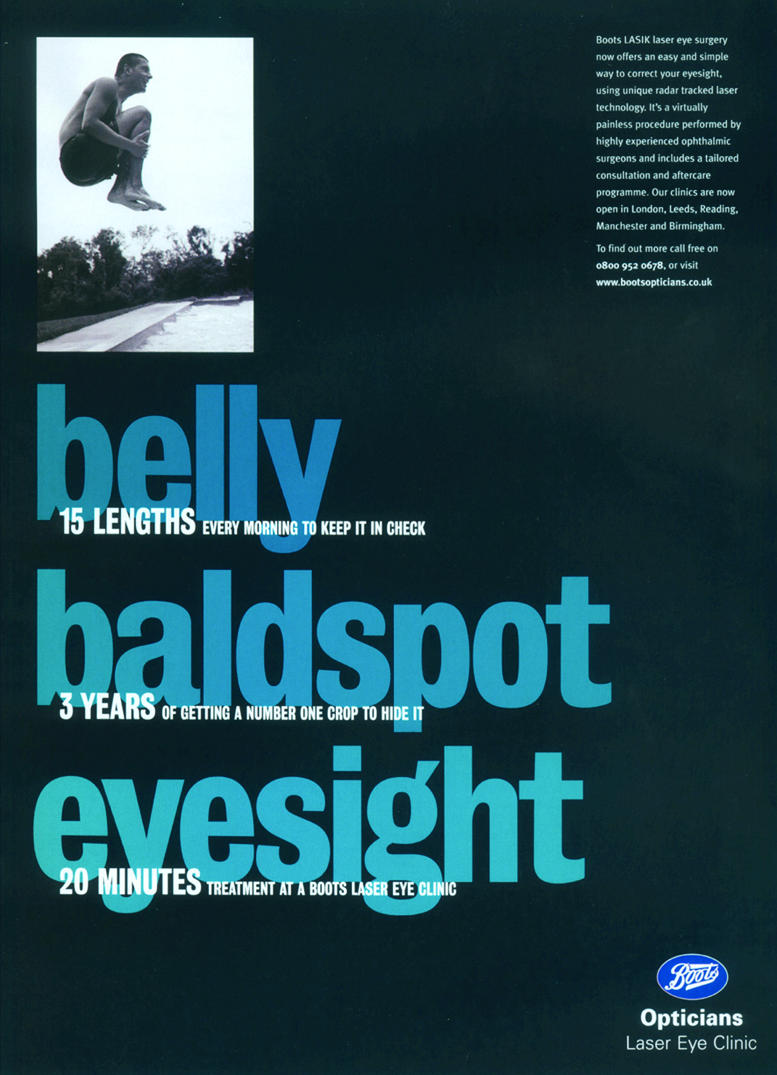

Men receive significantly less of doctor's time in medical encounters than women, and men are provided with fewer and briefer explanations—both simple and technical.1 Although men are more likely to have high risk behaviour, they receive less advice about changing risk factors than women do during checkups. For example, only 29% of doctors routinely provide age appropriate instruction on testicular self examination, compared with 86% who provide instruction to women on breast self examination.1 Well man clinics are nowhere near as ubiquitous as well woman clinics and did not take off when they were introduced in the early 1990s. However, some clinics have been successful, and perhaps the area needs to be revisited.11

Alternatives to general practitioners

Nurses have taken on increased responsibilities for health care over recent years, and this trend is set to continue. Most practice nurses are women, and although some men prefer consultations with female health professionals, particularly over sexual orientation, lack of choice could be a factor in the decision whether to consult. Men may be deterred from using new services like NHS Direct and walk-in centres because they are led by nurses.

Men also access health information from pharmacists much less than do women. This is a logical consequence of the fact that women use pharmacist services more than men for obtaining both oral contraceptives and prescription only medicines. Current and future trends in health policy are likely to increase pharmacists' roles and responsibilities. The increasing number of “self test” kits could expand the role of pharmacists in diagnosis, and they may even be able to give some definitive treatment. Companies such as Consignia and Du Pont are already looking at the health of their employees in a much broader sense, not least through well man clinics. Du Pont recently won an award for their male health initiatives, and Consignia is working with the Men's Health Forum on a project to raise awareness of prostate conditions.

Initiatives introduced by the current government include NHS Direct, NHS Direct Online, walk-in primary care centres, and information booths in places such as shopping centres. The popular NHS Direct Online is used equally by both sexes. The potential for helplines is shown by the success of the Impotence Association helpline, which receives tens of thousands of calls from men about erectile dysfunction—a subject it would be assumed most men would be reluctant to discuss. It shows the merits of an anonymous, confidential service for men.

Conclusion

Many myths surround men's health, the greatest of which is that men do not care about their health. The fact is that men worry about health but feel unable to talk about their concerns or seek help until it is often too late. This is all confounded by the impact of social class, with morbidity and mortality increasing in direct proportion to the level of deprivation. Solutions are not always immediately at hand. Men's health is a very young issue, but evidence based studies of areas such as education, health promotion, and better use of health services are increasing.12 The Men's Health Forum seeks a fundamental change in school education, placing health on the national curriculum; greater provision of alternative services such as NHS Direct Online and walk-in centres; improved use of occupational health services for health promotion; multidisciplinary approaches to suicide prevention; and an awareness of gender when health bodies structure health policies. Without these changes, the NHS will effectively remain a no man's land.

Figure.

Men's health: more than just beer guts and baldness

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Courtenay WH. Behavioural factors associated with disease: injury and death among men: evidence and implications for prevention. Journal of Men's Studies. 2000;9:81–142. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francome C. Improving men's health. London: Middlesex University Press; 2000. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Good GE, Dell DM, Mintz LB. Male role and gender role conflict: relations to help seeking in men. Journal of Counselling Psychology. 1989;36:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClure GMG. Suicide in children and adolescents in England and Wales, 1970-1998. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:469–474. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White A, Johnson M. Men making sense of their chest pain—niggles, doubts and denials. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9:534–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd T. Men and health: the context for practice. In: Davidson N, Lloyd T, editors. Promoting men's health: a guide for practitioners. London: Ballière Tindall; 2001. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biddulph M, Blake S. Moving goalposts: setting a training agenda for sexual health work with boys and young men. London: Family Planning Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jewell D. Primary care. In: Davidson N, Lloyd T, editors. Promoting men's health: a guide for practitioners. London: Ballière Tindall; 2001. pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilke G, Freeman S. Being a good enough GP. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin RM, Sterne JAC, Mangtani P, Majeed A. Social and economic variation in general practice consultation rates amongst men aged 16-39. National Statistics Quarterly 2001;Spring 09:29-36.

- 11.Kirby MG. Setting up a well man clinic in primary care. In: Kirby RS, Kirby MG, Farah RN, editors. Men's health. Oxford: Isis Medical Media; 1999. pp. 321–344. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Men's Health Forum database. www.menshealthforum.org.uk (accessed 9 October 2001).