Minimally invasive surgery is the most important revolution in surgical technique since the early 1900s. Its development was facilitated by the introduction of miniaturised video cameras with good image reproduction. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was the first procedure to be widely accepted, and several others are now well established. Other procedures are being validated, but further use of the technique may partly depend on the development of new enabling technologies. For example, a virtual reality laparoscopic simulator was recently used to assess the value of a three dimensional laparoscopic camera system.1 We present an overview of advances in minimal access surgery, concentrating on procedures that have most recently become established in everyday surgical practice.

Methods

We selected the topics to be discussed after consultation with the other surgeons in our department. We then conducted a literature search (Medline 1993-2000) separately for each section of the paper. Because of the broad nature of the topics covered, we have generally cited good quality reviews rather than the original papers.

Technological sea change

Laparoscopy has been well established in gynaecology for many years, but the technique was adopted much more slowly in surgery. This is mainly because of the early limits of the technology. Gynaecologists used a purely optical telescope for illumination and visualisation and operated unassisted. With one hand on the telescope, the gynaecologist had only one hand to manipulate the viscera, and thus the technical repertoire was limited.

The development of miniaturised television cameras that give an adequate image was key in the minimal access revolution. It allowed the assistant to have the same view as the surgeon. The assistant could therefore hold the camera (allowing the surgeon to operate with two hands) and retract the viscera to improve the access. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was soon shown to be possible, and rapidly became the procedure of choice.2 The principles that were developed for laparoscopic cholecystectomy have now been applied to many other abdominal and thoracic operations.

Recent advances

Minimal access surgery has moved the focus of surgery towards reducing the morbidity of patients while maintaining quality of care

Minimal access surgical techniques are now routine for cholecystectomy, Nissen fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, splenectomy, and adrenalectomy

Use of sentinel node biopsy is minimising the morbidity associated with staging breast cancer

Surgical robotics systems will enable a further revolution in minimally invasive techniques

Future developments are likely to be fuelled by patient demand

The importance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was the cultural change it engendered rather than the operation it replaced. In terms of technique, the focus of attention shifted from the surgeon's virtuosity to minimising the morbidity experienced by the patient.3 In a paper published in 1996 on laparoscopic adrenalectomy, the postoperative inpatient stay was decreased from 9.8 to 5.1 days.4 The next year, a second group reported a total inpatient stay as low as 2.4 days.5

Minimally invasive abdominal surgery

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication

Advances in the pharmacological management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease have been accompanied by a surge of interest in surgical management of this condition. There are three reasons for this. Firstly, although the indications are that long term drug treatment is safe, it is very expensive. Estimated annual costs to the NHS for H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitors for patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease are £60m and £90m respectively. Many of these patients could be treated by surgery.

Secondly, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is difficult to diagnose. Oesophageal manometry and pH monitoring are increasingly used to improve diagnostic accuracy. Better case selection will lead to better long term results from surgery.

Thirdly, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication has been shown to be technically feasible, safe, and effective and have a low rate of conversion to open surgery.6 Although fundoplication is highly effective for controlling gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, it is unclear whether the cost savings of laparoscopic surgery over lifelong drug treatment justify the (admittedly much reduced) inconvenience and morbidity of surgery. These issues are about to be investigated in the UK collaborative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease trial run by the health service's research unit at the University of Aberdeen (www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/hta/reflux.hti).

Minimal access techniques

Established

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Diagnostic laparoscopy

Laparoscopic appendicectomy

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication

Laparoscopic (or thoracoscopic) Heller's myotomy25

Laparoscopic adrenalectomy

Laparoscopic splenectomy

Thoracoscopic sympathectomy

Laparoscopic rectopexy26

Under evaluation

Laparoscopic hernia repair

Laparoscopic colectomy

Laparoscopic nephrectomy for living related donor transplant

Parathyroidectomy (guided with hand held gamma probe)

Laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation27

Prospects

Sentinel node biopsy

Hepatic resection

Gastrectomy

Inguinal hernia repair

Inguinal hernia is common, and effective minimal access techniques have been developed. However, these techniques have not been adopted as widely as, for example, laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The first reason for this is that minimal access techniques were first advocated at the peak of a revolution in open surgical technique: the adoption of the open, tension-free mesh (Lichtenstein) repair.7 The Lichenstein repair was shown to have recurrence rates tenfold lower than those of the Shouldice repair, which was then the standard technique. The surgical community embraced the new technique,8 and further technical revolution was, unsurprisingly, met with scepticism. This scepticism was compounded by the fact that several techniques were proposed. The intraperitoneal on-lay mesh had an unacceptable rate of late complications and has been abandoned—the remaining techniques are both safe and effective.9

A further issue is the difficulty of showing a large benefit in terms of patient recovery (a key feature of minimally invasive surgery) because open surgery is so well tolerated by most patients. Long term recurrence rates are not available yet, but indications are that they do not differ significantly from those with the Lichtenstein repair. Minimal access techniques are, however, thought to offer a clear technical benefit in patients with recurrent and bilateral hernias. This is because patients having minimally invasive bilateral repair require only one set of three midline incisions (the same as for unilateral repair) whereas those having open repair require bilateral groin incisions and because the laparoscopic approach allows the surgeon to operate on unscarred tissues in a case of recurrent hernia.

Laparoscopic colectomy

Laparoscopic colectomy is technically demanding, and most surgeons have been reluctant to invest the time in mastering the procedure.10 Nevertheless, centres that have gained sufficient expertise report benefits in terms of patients' comfort and disability, length of stay, and cost.11 Concerns have been raised over the safety of laparoscopic surgery for cancer after early reports of recurrence at the port site.12 Certain laparoscopic devices have also been suggested to increase the risk of such lesions, although experimental work seems to refute this possibility.13 Multicentre prospective randomised trials are in progress in Britain and the United States (protocol numbers MRC-CLASICC and NCCTG-934653 trial: see http://cancernet.nci.nih.gov/trialsrch.shtml). If the results of such trials are favourable, consumers are likely to demand this procedure. Training large numbers of surgeons in the technique will pose a challenge to the surgical community.

Hand assisted surgery

Development of hand assisted surgery has gained impetus from the efforts in laparoscopic colonic surgery.14 The surgeon's hand is introduced into the peritoneal cavity through a small incision, and a proprietary sleeve and cuff are used to maintain pneumoperitoneum. This allows direct palpation of the viscera and facilitates retraction and mobilisation of the colon. The incision through which the hand is introduced can also be used to remove specimens or bring the ends of the colon to the surface for extracorporeal anastomosis. Such operations are often termed laparoscopically assisted because the main part is done outside the body, with laparoscopy minimising the size of wound necessary for mobilisation and resection.

Laparoscopic splenectomy

Laparoscopic splenectomy is the procedure of choice for removing a normal sized spleen.15,16 Use of the laparoscopic approach for massively enlarged spleens is still controversial, mostly because of the difficulty in manipulating the spleen and the consequent risk of bleeding.17 New laparoscopic instruments, such as the ultrasonic dissector and atraumatic grasper, may make minimally invasive procedures feasible for more patients. Hand assisted techniques are well accepted for splenectomy.

Laparoscopic adrenalectomy

Laparoscopic adrenalectomy was first reported in 199218 and is now used for most patients with adrenal abnormalities.5 Reservations remain about using this approach in patients with phaeochromocytoma, although several authors have shown it is safe.19,20 Malignant disease that has breached the capsule is regarded as a contraindication, as is the presence of para-aortic lymphadenopathy. Various approaches have been used, but the consensus supports a transperitoneal approach in the lateral position.21

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

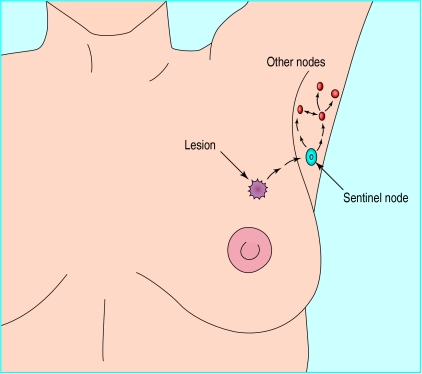

The introduction of sentinel node biopsy techniques in breast surgery has the potential to limit the need for full axillary dissections to patients with positive axillary nodes.22 Open surgery in conjunction with a dye and radioisotope tracer is used to identify the first axillary node to drain in a given area of the breast (fig 1). This “sentinel node” is then removed and examined for metastases—the status of the sentinel node has good predictive value compared with a full axillary dissection.22 The technique is considered a minimal access technique because the primary endpoint (delineation of the nodal status of the axilla) is determined through a small incision, with minimal morbidity for the patient.

Figure 1.

Sentinel node biopsy. Lymph fluid from the lesion drains to the sentinel node and then on to other nodes in the axillary group. The region of the lesion is injected with a blue dye and radioisotope tracer. Gamma camera images show the location of the sentinel node, and a small incision is made directly over it. The blue dye outlines the lymphatics and the sentinel node

Minimal access techniques have also been adapted to surgery in the axilla, and initial results are encouraging.23 Thus, for patients in whom the primary tumour is suitable for breast conservation techniques, the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of the disease may all be able to done by minimal access techniques, probably on an outpatient basis. This technique has also been applied in the treatment of malignant melanoma, and is potentially useful in other settings.

Robotics in surgery

Robotics is rapidly developing in surgery, although the word is slightly misused in this connection. None of the systems under development involves a machine acting autonomously. Instead, the machine acts as a remote extension of the surgeon. The correct term for such a system is a “master slave manipulator,” although it seems unlikely that this term will gain general currency.

Minimal invasive surgery is itself a form of telemanipulation because the surgeon is physically separated from the workspace. Telerobotics is an obvious tool to extend the surgeons' capabilities. The goal is to restore the tactile cues and intuitive dexterity of the surgeon, which are diminished by minimal invasive surgery. A slave manipulator, controlled through a spatially consistent and intuitive master with a force feedback (haptic) system, could replace the tactile sensibilities and restore dexterity.

Several passive mechanical devices, primarily used to hold the telescope, have been developed as assistants for general laparoscopic surgery. They successfully reduce the stress on the surgeon by eliminating the inadvertent movements of a human assistant, which can be distracting and disorienting.24

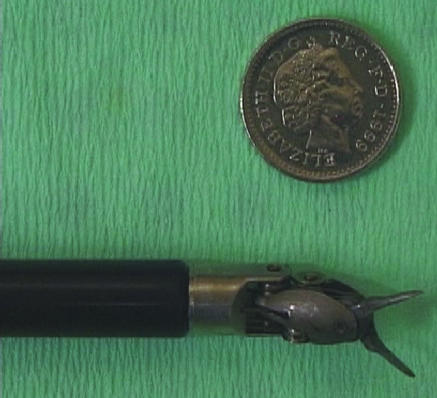

One master slave system that is currently being tested is the da Vinci surgical system. It has two primary components: the surgeon's viewing and control console, and the surgical arm unit, which holds and manipulates the detachable surgical instruments (fig 2). These pencil sized instruments with tiny electromechanically controlled “wrists” duplicate the movement of the surgeon's hand and wrist at the operative site (fig 3).

Figure 2.

Effector arms of da Vinci surgical system. The attached instruments are controlled by the surgeon, who sits at an adjacent console

Figure 3.

Effector tips of the da Vinci surgical system incorporate miniature wrists that allow them to mimic any movement made by the surgeon at the control console

“Motion scaling” software is used to translate large natural movements to extremely precise micromovements. Surgeons can immediately observe the instruments in the patient's body respond to the movements of their hands on the handles, as if they were performing the operation directly. This avoids the need for the reversed counterintuitive motions used in minimally invasive surgery.

This system is in use in several centres, and the repertoire of procedures is increasing steadily. An interesting spin-off is its use in open procedures that require extreme precision—for example, microvascular anastomosis and nerve repair. In such settings, the robot can enhance the surgeons skills by eliminating physiological tremor.

Additional educational resources

Key review articles

Memon MA, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr. The role of minimal access surgery in the acute abdomen. Surg Clin N Am 1997;77:1333-5.

Shah J, Mackay S, Rockall T, Vale J, Darzi A. Urobotics: robotics in urology. BJU Int 2001;88:313-20.

Davies B. A review of robotics in surgery. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 2000;214:129-40.

Useful websites

Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons' Primary Care Physicians Resource Center(www.sages.org/primarycare/index.html)

British Journal of Surgery online (www.bjs.co.uk/randomised.htm)

Scientific surgery website lists randomised controlled trials in surgery along with a brief summary of each study

Footnotes

Competing interests: Da Vinci sponsor a PhD student in AD's department.

References

- 1.Taffinder N, Smith SG, Huber J, Russell RC, Darzi A. The effect of a second-generation 3D endoscope on the laparoscopic precision of novices and experienced surgeons. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1087–1092. doi: 10.1007/s004649901179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1999;44:187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grace P, Quereshi A, Darzi A, McEntee G, Leahy A, Osborne H, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a hundred consecutive cases. Ir Med J. 1991;84:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutherford J, Stowasser M, Tunny T, Klemm S, Gordon R. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. World J Surg. 1996;20:758–761. doi: 10.1007/s002689900115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagner M, Pomp A, Heniford BT, Pharand D, Lacroix A. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: lessons learned from 100 consecutive procedures. Ann Surg. 1997;226:238–246. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00003. [discussion 246-7]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowrey DJ, Peters JH. Current state, techniques, and results of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Semin Laparosc Surg. 1999;6:194–212. doi: 10.1053/SLAS00600194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK, Montllor MM. The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg. 1989;157:188–193. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK. The cause, prevention, and treatment of recurrent groin hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:529–544. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cocks JR. Laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty: a comparison between transperitoneal and extraperitoneal techniques. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:506–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darzi A, Hill AD, Henry MM, Guillou PJ, Monson JR. Laparoscopic assisted surgery of the colon. Operative technique. Endosc Surg Allied Technol. 1993;1:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darzi A, Lewis C, Menzies-Gow N, Guillou PJ, Monson JR. Laparoscopic abdominoperineal excision of the rectum. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:414–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00187163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nduka CC, Monson JR, Menzies-Gow N, Darzi A. Abdominal wall metastases following laparoscopy. Br J Surg. 1994;81:648–652. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nduka CC, Poland N, Kennedy M, Dye J, Darzi A. Does the ultrasonically activated scalpel release viable airborne cancer cells? Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1031–1034. doi: 10.1007/s004649900774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott HJ, Darzi A. Tactile feedback in laparoscopic colonic surgery. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1005. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klingler PJ, Tsiotos GG, Glaser KS, Hinder RA. Laparoscopic splenectomy: evolution and current status. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1999;9:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ. Laparoscopic splenectomy. World J Surg. 1999;23:384–388. doi: 10.1007/pl00012313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terrosu G, Donini A, Baccarani U, Vianello V, Anania G, Zala F, et al. Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy in the management of splenomegaly: our preliminary experience. Surgery. 1998;124:839–843. . [correction Surgery 1999;125:154.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagner M, Lacroix A, Bolte E. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in Cushing's syndrome and pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1033. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210013271417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miccoli P, Bendinelli C, Materazzi G, Iacconi P, Buccianti P. Traditional versus laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of pheochromocytoma: a preliminary study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1997;7:167–171. doi: 10.1089/lap.1997.7.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagner M, Breton G, Pharand D, Pomp A. Is laparoscopic adrenalectomy indicated for pheochromocytomas? Surgery. 1996;120(6):1076–1079. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80058-4. [discussion 1079-80]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagner M, Lacroix A, Bolte E, Pomp A. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. The importance of a flank approach in the lateral decubitus position. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:135–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00316627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, Galimberti V, Luini A, Zurrida S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection in breast cancer: results in a large series. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:368–373. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsangaris TN, Trad K, Brody FJ, Jacobs LK, Tsangaris NT, Sackier JM. Endoscopic axillary exploration and sentinel lymphadenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:43–47. doi: 10.1007/s004649900895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba S, Ito K, Yanaihara H, Nagata H, Murai M, Iwamura M. Retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy by a lumbodorsal approach: clinical experience with solo surgery. World J Urol. 1999;17:54–58. doi: 10.1007/s003450050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monson JR, Darzi A, Carey PD, Guillou PJ. Thoracoscopic Heller's cardiomyotomy: a new approach for achalasia. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darzi A, Henry MM, Guillou PJ, Shorvon P, Monson JR. Stapled laparoscopic rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:301–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00187773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darzi A, Cheshire NJ, Somers SS, Super PA, Guillou PJ, Monson JR. Laparoscopic omental patch repair of perforated duodenal ulcer with an automated stapler. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1552. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800801221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]