A tetraplegic woman on a ventilator made legal history last week when she became the first patient in the United Kingdom to go to court in a bid to have the ventilator switched off.

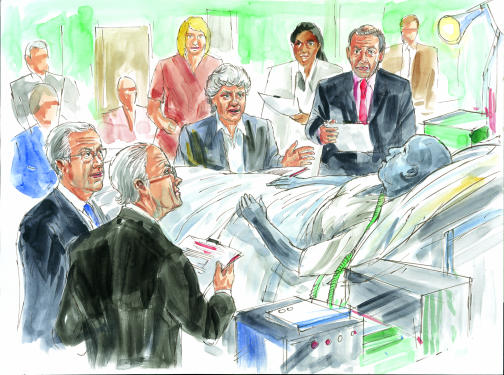

The case made headlines when the High Court convened at the woman's bedside in an intensive care unit, with the scene relayed by video to family, friends, and reporters in the courtroom.

In another first, the rest of the two and a half day hearing, which took place at the royal courts of justice in central London, was watched by the woman on a video screen in her room. Propped up on pillows and attended to by her carers, she could be seen on three large screens in the courtroom, following the case intently.

The hearing ended last Friday (8 March), with judgment not likely to be given until after Easter. A court order bans identification of the woman—a 43 year old former senior social worker—the hospital where she is being cared for, the NHS trust that runs it, and any doctors involved in her current care or likely to care for her in the future.

She had a haemorrhage into a cavernous haemangioma in her upper spinal cord in 1999, from which she made an almost complete recovery, but became tetraplegic after a major re-bleed in February 2001. She is completely dependent on the ventilator, although she can swallow and can talk with the aid of a speech synthesiser.

The woman, named Miss B in the court case, has asked repeatedly over the last year for the ventilator to be switched off, but the doctors caring for her have refused. They told the court they had ethical objections to—as they see it— causing her death. Under English law patients who are mentally competent to take decisions on treatment cannot be forced to undergo treatment against their will.

As long ago as April 2001 the trust's solicitors advised that it would be entirely lawful to switch the ventilator off if Miss B was competent to decide. Last August an independent psychiatrist reported that she was competent, and two other psychiatrists instructed for the court case have confirmed the finding, though the psychiatrist briefed by the trust says the fact that she is being cared for in a high dependency unit in an acute hospital could amount to a “temporary factor” eroding her capacity. The Official Solicitor, who is advising the court, accepts that she is fully capable of taking her own decisions, and there seems little, if any, doubt that she will get her wish.

She may also obtain a ruling that the trust has been treating her unlawfully at least since August. Miss B risked her life savings to bring the case, though the trust, probably bowing to the inevitable, has now agreed to pay her legal costs.

Robert Francis QC, for the trust, suggested that Miss B's relationship with her doctors and trust management and her anger at the way she was being treated could render her unable to balance matters in her mind—part of the test for competence.

The judge, Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, said she found that argument unattractive. “She is getting very annoyed because they won't listen to her. To suggest that her anger and its effect on her relationships should be treated as a loss of capacity is to underestimate the feelings of patients in hospitals.

“She is angry with them for treating her in a paternalistic way, as though she isn't fit to make a decision. If you are lying there and not being listened to, I'm not sure this goes to lack of capacity. A lot of patients would absolutely object to that.

“Serious frustration and anger are natural emotions. You have to go a long way to say that distorts capacity.”

Mr Francis said that Miss B's doctors, who disagreed with her decision, were understandably concerned to establish that she was competent to make it, because of the gravity of the decision.

Dame Elizabeth said: “You seem to be saying that if you want something and the doctors don't think it is a good idea because they want to do something else, the more you disagree the more you will be regarded as unable to make a decision.

“That is a dangerous concept. There is a very paternalistic element. It's a very ‘doctor knows best’ concept. I really bridle at that as a member of the public as well as a judge.”

Figure.

SíAN FRANCIS

The High Court last week convened at the bedside of Miss B