Abstract

The ADAMTS (a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs) family metalloprotease MIG-17 plays a crucial role in the migration of gonadal distal tip cells (DTCs) in Caenorhabditis elegans. MIG-17 is secreted from the body wall muscle cells and localizes to the basement membranes (BMs) of various tissues including the gonadal BM where it regulates DTC migration through its catalytic activity. Missense mutations in the BM protein genes, let-2/collagen IV a2 and fbl-1/fibulin-1, have been identified as suppressors of the gonadal defects observed in mig-17 mutants. Genetic analyses indicate that LET-2 and FBL-1 act downstream of MIG-17 to regulate DTC migration. In addition to the control of DTC migration, MIG-17 also plays a role in healthspan, but not in lifespan. Here, we examined whether let-2 and fbl-1 alleles can suppress the age-related phenotypes of mig-17 mutants. let-2(k196) fully and fbl-1(k201) partly, but not let-2(k193) and fbl-1(k206), suppressed the senescence defects of mig-17. Interestingly, fbl-1(k206), but not fbl-1(k201) or let-2 alleles, exhibited an extended lifespan compared to the wild type when combined with mig-17. These results reveal allele specific interactions between let-2 or fbl-1 and mig-17 in age-related phenotypes, indicating that basement membrane physiology plays an important role in organismal aging.

Introduction

The BMs are complex structures composed of multiple types of molecules. To maintain their integrity, it is necessary to appropriately remove damaged components and incorporate new ones, ensuring proper turnover. However, as animals age, the metabolism of BMs slows down, leading to the accumulation of damage [1]. Collagen levels decrease with age, while spontaneous cross-links increase. Yet, the anti-aging effects of BMs remain poorly understood. In the skin, BM collagen is essential for stem cell maintenance through hemidesmosomes [2]. Loss of collagen is known to impair cell competition, thus contributing to aging. However, the relationship between BMs and the suppression of aging beyond skin stem cells remains unknown.

The ADAMTS family of zinc metalloproteases is a group of enzymes that play important roles in various biological processes by cleaving proteins in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and regulating the structure and function of tissues in the body [3]. Dysregulation of ADAMTS enzymes can contribute to various diseases and disorders, including arthritis, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer [4]. Although the functions of ADAMTS proteases in animal development and pathologies are well studied, their roles in organismal aging and lifespan remain mostly unsolved. In this study, we analyzed the functions of one of the C. elegans ADAMTS enzymes, MIG-17, in aging and lifespan.

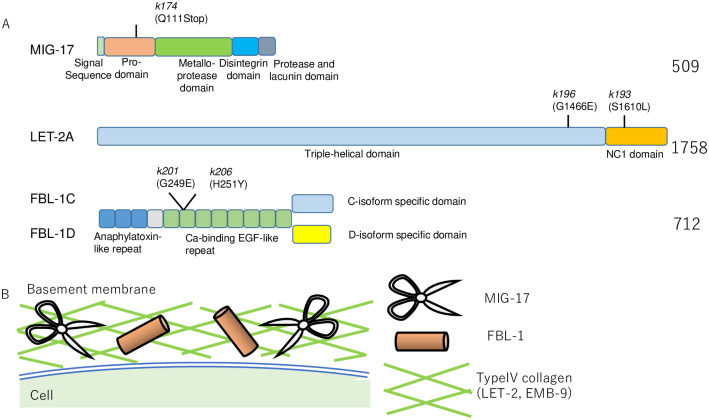

MIG-17 is secreted from the body wall muscle cells as a proform and localizes to the BMs of various tissues, including gonad, intestine, body wall muscle, and hypodermis, where it is activated by auto-catalytic removal of its prodomain [5, 6] (Fig 1A and 1B). The protease activity of MIG-17 in the BM of DTCs is sufficient to regulate the directional migration of DTCs to generate the U-shaped gonad arms. In mig-17 mutants, the DTCs meander and stray, resulting in an abnormal gonadal shape [7]. Dominant gain-of-function (gf) mutations in the BM molecules collagen IV α2 chain and fibulin-1 suppress the gonadal defect of the mig-17 mutants [8–10] (Fig 1A). let-2(gf) mutations are amino-acid substitutions either in the triple helical domain or in the C-terminal non-collagenous 1 (NC1) domain (Fig 1A). fbl-1(gf) mutations are amino-acid substitutions found in the second EGF-like motif (Fig 1A). Genetic analyses revealed a regulatory pathway in which MIG-17 recruits and activates FBL-1C (C isoform), which then recruits NID-1 to the BM to control DTC migration. MIG-17 also activates collagen IV to induce nidogen-dependent and -independent pathways to control DTC migration [9]. In addition to its role in in gonadogenesis, MIG-17 also functions in regulating healthy aging. mig-17 mutants exhibit an earlier decline in periodic behaviors, including the defecation cycle and pumping rate, as well as a decrease in motility rate, and show earlier shortening of body length compared to the wild type. [11].

Fig 1. Schematic diagrams of MIG-17, FBL-1C, and LET-2A.

(A) The mutation sites of mig-17(k174), let-2(k193, k196), and fbl-1(k201, k206) are indicated. (B) A diagram showing the localization of MIG-17, LET-2, and FBL-1. These proteins are components of BMs.

In the present study, we examined the effects of suppressor mutations let-2 and fbl-1 on the age-dependent phenotypes of mig-17 mutants. We found that let-2 and fbl-1 mutations suppressed the mig-17 defects in an allele-specific manner.

Materials and methods

Strains and genetic analysis

Culture and handling of C. elegans were conducted as described [12]. Worms were cultured at 20°C. The following mutations and transgenes were used in this work: mig-17(k174), fbl-1(k201, k206), let-2 (k193, k196) [7–9].

Microscopy

Gonad migration phenotypes were scored using a DIC images of Nomarski microscope (Axioplan 2; Zeiss). Gonad migration phenotypes were scored using DIC images captured with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope [13].

Analysis of growth rate

The growth rate was analyzed as described [14]. Briefly, newly hatched larvae were synchronized for one hour, grown at 20°C, and the growth rate was assessed based on the stages of vulval development at the L4 stage. A simple invagination occurs in early L4, followed by a Christmas tree-like invagination in mid-L4, and the invagination becomes mostly closed in late L4.

Analysis of body length

Body length was analyzed as previously described [11]. Briefly, young adult animals were collected as day 1 adults for synchronization. Body length was measured by ImageJ software. To measure body length, we traced a line along the body using ImageJ and then measured its length.

Behavioral analyses

Defecation cycle and pumping rate were analyzed as previously described [11]. Briefly, average of five defecation cycles were scored for individual animal. If the defecation cycle exceeded 3 minutes, further measurements were discontinued. Number of pumps during 30 seconds were counted and the average of three independent measurements was calculated for each individual.

Analysis of lifespan

Lifespan was analyzed as previously described [11]. Three independent experiments are performed. Synchronization was performed by collecting L4 animals. Animals were transferred to new OP50 seeded plates for every two days during reproduction period, and every three days during post-reproduction period.

Statistics

Growth rates were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test to compare adults and larvae.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using Excel to compare defecation cycle, pumping rate, and body length. If a significant difference was found by ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed using Excel statistics [15].

The lifespan was analyzed using a log-rank test in R [11].

Results

fbl-1(k201) mutation suppresses growth retardation of mig-17 mutants

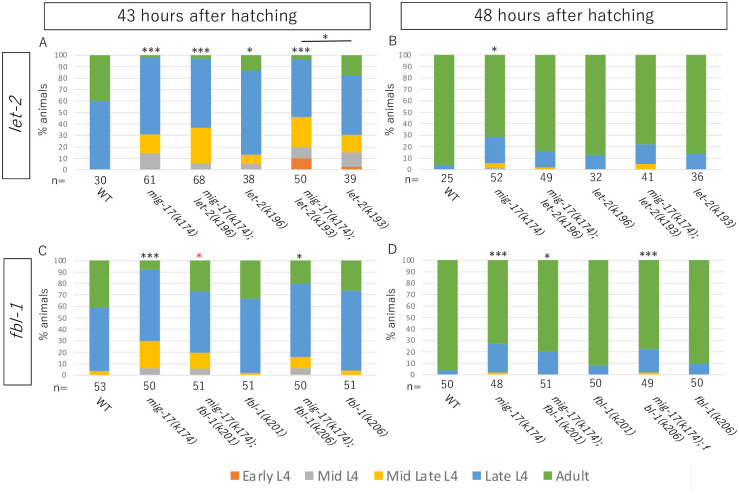

We previously reported that dominant gain-of-function mutations in let-2 and fbl-1could suppress the gonadal defects of mig-17 mutants (S1 Fig). We examined whether mig-17 and the suppressor mutations affect the larval growth rate. The growth of C. elegans from hatched larvae to adults involves four larval stages, namely larval stage 1 (L1) to L4, punctuated by molting. We first examined whether MIG-17 is required for normal growth rate. We synchronized the newly hatched larvae for one hour and grew them at 20°C. The growth rate was assessed by monitoring the stages of vulval development at the L4 stage, as described [14]. Our observations revealed that mig-17 mutants exhibited slower growth compared to wild-type animals (Fig 2A–2D). Since the gain-of-function mutations in collagen IV, let-2(k193) and let-2(k196), and fibulin-1, fbl-1(k201) and fbl-1(k206) suppress the gonadal defects of mig-17 mutants [8, 10], we further investigated whether they could also alleviate the growth retardation observed in mig-17 mutants. let-2(k193) and let-2(k196) mutants also displayed growth retardation (WT vs let-2(k196) p = 0.058). These let-2 mutations failed to suppress the slow growth observed in mig-17 mutants. Instead, let-2(k193) seemed to exacerbate the phenotype of mig-17 at 43 hours, as evidenced by the presence of 10% early L4 animals, a feature not observed in mig-17 alone (Fig 2A and 2B). The mutations fbl-1(k201) and fbl-1(k206) did not significantly impact the growth rate, and only fbl-1(k201) exhibited a weak suppression of mig-17 growth retardation at 43 hours (Fig 2C). These results indicate that although both the let-2 and fbl-1 alleles are strong suppressors of the gonadal defects of mig-17, they mostly fail to suppress the growth defect of mig-17.

Fig 2. Suppressors of the gonadal defects of mig-17 fail to suppress the growth defect.

Bar graphs represent developmental stages at 43 or 48 hours after hatch. The sample size is indicated at the bottom of each bar graph. Percentages of adult animals and those of L4 animals were compared in 43 and 48 hours, respectively. Black and red asterisks on the top of bar graph indicate p-values for Fisher’s exact test against WT and mig-17(k174), respectively: ***p < 0.005, *p < 0.05.

Suppression of short healthspan in mig-17 mutants

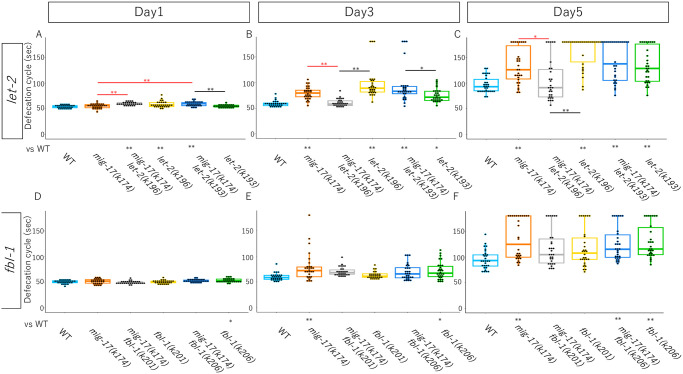

Aged decline in the defecation cycle and pumping rate are often used as indicators of senescence rate in C. elegans [11, 16, 17]. We examined the defecation cycle of wild type and mig-17 mutant animals. The cycle was around 50 seconds at the young adult stage (day 1) and extended to 90 seconds until day 5 in the wild type (Fig 3A–3F). Although mig-17 mutants showed a cycle comparable to the wild type at day 1, it became significantly longer after day 3 compared to the wild type, suggesting that the senescence rate of mig-17 mutants is faster than that of the wild type (Fig 3A–3F) [11]. We then investigated whether the let-2 and fbl-1 mutants could suppress the mig-17 defect. Both let-2 alleles showed a significantly longer defecation cycle compared to the wild type from day 1 to day 5. Interestingly, however, let-2(k196), but not let-2(k193), strongly suppressed the mig-17 defecation decline at day 3 and day 5 (Fig 3A–3C). Thus, mig-17(k174) and let-2(k196) can suppress each other for their defecation defects. fbl-1(k206) alleles showed significantly longer defecation cycles compared to the wild type after day 5 and fbl-1(k201) showed a trend toward suppression of the mig-17 defecation decline at day 5, although it was not statistically significant (t-test:p = 0.069) (Fig 3D–3F).

Fig 3. Suppression of slow defecation cycle in aged mig-17 mutants by let-2(k196).

Box and dot plots indicate the defecation cycle. The sample size is 30 animals. p-values against WT is indicate at the bottom of plots. p-values against mig-17(k174) are indicated by red asterisks. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons: *p≤ 0.05, **p≤ 0.01.

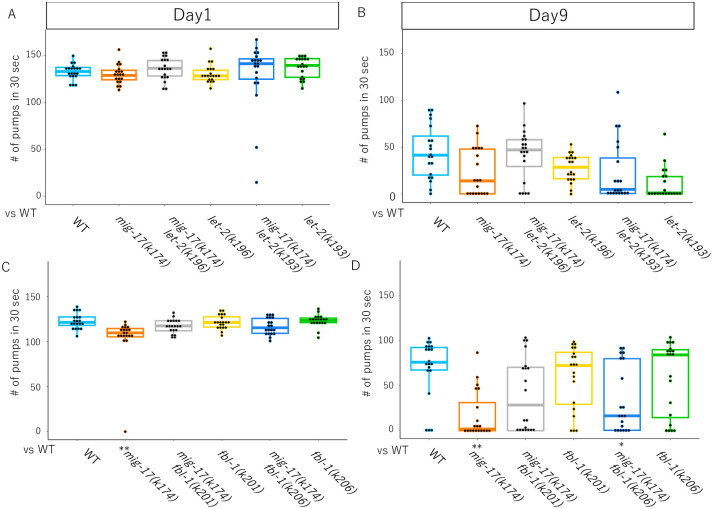

We examined pharyngeal pumping rates at day 1 and day 9 adults. The pumping rates decreased by 50% in day 9 adults. The pumping rates of mig-17 adults were much slower than those of wild type at day 1 and day 9, suggesting short healthspan of mig-17 animals (Fig 4C and 4D) [11]. Interestingly, let-2(k196), but not let-2(k193), showed a trend toward suppression of the mig-17 pumping rate decline at day 9 (Fig 4A and 4B), although it was not statistically significant. The pumping rate of mig-17(k174) (p = 0.0001) and fbl-1(k206) mig-17(k174) (p = 0.028), but not that of fbl-1(k201); mig-17(k174) (p = 0.105), showed significant differences from that of wild-type animals at day 9 adult (Fig 4C and 4D).

Fig 4. Suppression of slow pumping rate in aged mig-17 mutants by let-2(k196) and fbl-1(k201).

Box and dot plots indicate the number of pumping in 30 seconds. Sample size is 20 animals. p-values against WT is indicate at the bottom of plots. p-values against mig-17(k174) are indicated by red asterisks. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons: *p≤ 0.05, **p≤ 0.01.

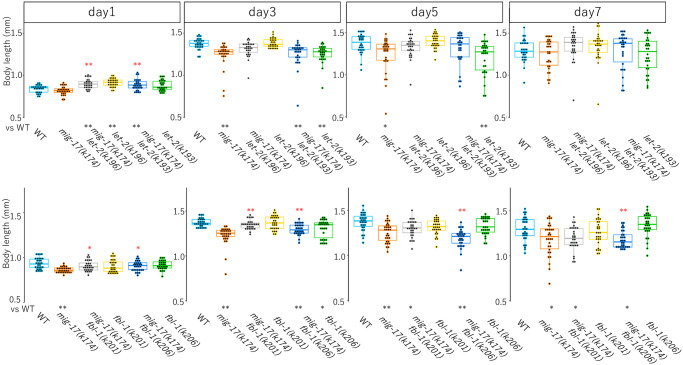

We then examined age-dependent alteration of body length. In wild-type animals, the body length increased until day 3 to day 5 and gradually deceased after day 7 (Fig 5A and 5B). Although mig-17 animals showed body length similar to that of the wild type at day1, their body lengths at day 3 and day 5 were significantly shorter than those of the wild type (Fig 5A and 5B) [11]. The body length of day 1 adults was longer in mig-17; let-2(k196) and mig-17; let-2(k193) double mutants compared to the wild type or mig-17 mutants. At the day3 adult, the body length of mig-17(k174) and let-2(k193) mig-17(k174), but not that of let-2(k196) mig- 17(k174), showed significant differences from those of wild-type animals (Fig 5A). Both fbl-1(k201) and fbl-1(k206) suppressed the short body size of mig-17 at day 1 to day 3 (Fig 5B).

Fig 5. Suppression of body length defects in mig-17 mutants by let-2 and fbl-1.

Box and dot plots indicate the body length. Standard deviation is indicated. The sample size is 30 animals. p-values against WT are indicated at the bottom of the plots. Red and blue asterisks on the top of bar indicate p-values against mig-17(k174) and let-2 or fbl-1, respectively. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons: *p≤ 0.05, **p≤ 0.01.

The fbl-1(k206) mutation extends the lifespan of mig-17 mutants

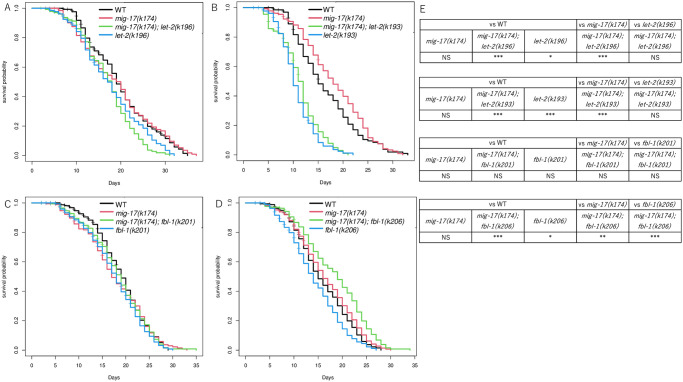

We examined the lifespan of mig-17 mutants and analyzed the effects of let-2 and fbl-1 mutations on lifespan. The lifespan analysis was conducted from the young adult stage. The mig-17 mutants exhibited a lifespan comparable to the wild type (Fig 6A–6D) as we have reported [11]. However, the lifespans of let-2(k193) and let-2(k196) animals were significantly shorter than the wild type or mig-17 mutants. The let-2(k193); mig-17 and let-2(k196); mig-17 double mutants also showed a shortened lifespan (Fig 6A, 6B and 6E). In contrast, the lifespans of fbl-1(k201) and fbl-1(k206) single mutants, as well as fbl-1(k201); mig-17 double mutants, were comparable to those of the wild type or mig-17 mutants (Fig 6C–6E). Interestingly, however, fbl-1(k206); mig-17 double mutants exhibited a significantly longer lifespan compared to the wild type. Thus, as observed in the age-related phenotypes, let-2 and fbl-1 mutations differentially affected the lifespan of mig-17 mutants. The extension of lifespan in fbl-1(k206); mig-17 double mutants, but not in fbl-1(k206) single mutants, implies that fbl-1(k206) mutation can extend lifespan in the absence of the MIG-17 protease (since mig-17(k174) represents a null allele).

Fig 6. Lifespan extension by mig-22(k185gf).

(A-D) Survival curve shows the effect of let-2(k193, k196) or fbl-1(k201, k206) mutations in the mig-17(k174) background. The x axis represents lifespan in days of adulthood. The y axis shows the fraction of worms alive. (E) Table shows p-values for logrank test are indicated as: ***p < 0.005, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, NS Not significant. The sample size is 180 animals.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the age-related phenotypes of the mig-17/ADAMTS mutant and its suppressor mutations for the gonadal defects in let-2/collagen IV and fbl-1/fibulin-1. The mig-17(k174) null mutant showed a normal lifespan but exhibited a slow growth rate and short healthspan, including earlier elongation of defecation cycle and a reduction of pharyngeal pumping rate. The mig-17 mutant also exhibited a defect in age-associated body length elongation. Despite all let-2 and fbl-1 alleles being robust suppressors of the mig-17 gonadal defects, they had differential effects on these mig-17 phenotypes.

As we observed in mig-17/ADAMTS mutants, growth retardation was also noted in Adamts1 as well as Adamts9/+; Adamts20 mutants in mice [18, 19]. Although the mig-17 mutants had no effect on lifespan, they exhibited phenotypes associated with short healthspan. While much of the research on ADAMTS proteases has focused on their roles in development and disease, some studies suggest that they may also have functions relevant to aging. For example, several ADAMTS proteases are induced in intervertebral disc degeneration during aging [20, 21]. Reduction of the reelin level by ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5-dependent degradation is associated with hyperphosphorylated tau protein, forming neurofibrillary tangles leading to Alzheimer’s disease [22]. However, these represent deleterious effects of ADAMTS on aging. In contrast, MIG-17 has a function to promote healthy aging, suggesting that MIG-17-dependent remodeling of the basement membrane is crucial for delaying the senescence process. We previously demonstrated that chondroitin proteoglycan acts downstream of MIG-17 to mediate healthy aging [11].

Both let-2 mutations shortened lifespan. Thus, both of these type IV collagen mutations have a negative impact on lifespan, although it is not clear whether these mutations directly affect lifespan. However, let-2(k196) suppressed the early prolongation of mig-17 defecation cycle associated with aging (Table 1). let-2(k196) also suppressed mig-17 for its insufficient increase in body length with aging. In contrast, let-2(k193) did not suppress any of these aging defects in mig-17. Type IV collagen molecules self-assemble into a complex mesh-like network within basement membranes. This network contributes to the mechanical integrity and resilience of basement membranes, allowing them to withstand mechanical stresses [23]. In addition to these structural functions, type IV collagen is also known to be involved in TGF-β signaling. For example, mutations in COL4A1 and COL4A2 impair triple helical assembly into protomers and their secretion, leading to intracellular accumulation and extracellular deficiency. Accordingly, semi-dominant COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations cause Gould syndrome characterized primary by cerebrovascular manifestation in which TGF-β signaling is overactivated [24]. Increased TGF-β1 and TGF-β-dependent SMAD3 signaling are associated with age-related aortic valve calcification in klotho knockout mice [25]. Interestingly, DAF-7/TGF-β regulates longevity through DAF-2/insulin signaling in C. elegans [26]. It may be possible that the let-2(k196) mutation alters the TGF-β signaling to correct the short healthspan of mig-17 mutants. Consistently, in humans, ADAMTS10, whose mutation causes Weill-Marchesani syndrome characterized by short stature and thickened skin, increases TGF-β activation in a dose-dependent manner [27, 28]. let-2(k196) is a missense mutation in the triple helical domain, whereas let-2(k193) is a missense mutation in the C-terminal NC1 domain of type IV collagen [9]. It might be possible that the triple helical domain may play a more important role than the NC1 domain in the regulation of aging.

Table 1.

| Phenotype | Developmental phenotype | Aging | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonad development | Growth rate | Defecation cycle | Pumping rate | Body length | Lifespan | |

| mig-17(k174) | Mig | Slow | Slow | Slow | Short | |

| mig-17(k174) let-2(k196) | Slow | Short | ||||

| mig-17(k174) let-2(k193) | Slow | Slow | Short | Short | ||

| let-2(k196) | Slow | Slow | Short | |||

| let-2(k193) | Slow | Short | Short | |||

| mig-17(k174) fbl-1(k201) | ||||||

| mig-17(k174) fbl-1(k206) | Slow | Slow | Slow | Short | Long | |

| fbl-1(k201) | ||||||

| fbl-1(k206) | Slow | Short | Short | |||

fbl-1(k201), but not fbl-1(k206), suppressed the growth retardation and early decline in pumping rate of mig-17. Furthermore, both fbl-1 alleles suppressed the insufficient growth of body length associated with aging in mig-17. fbl-1(k201) had no effect on lifespan, but fbl-1(k206) had a slightly shorter lifespan than the wild type. However, surprisingly, the mig-17(k174); fbl-1(k206) double mutant lived significantly longer than the wild type animals. Interestingly, fbl-1(k201) and fbl-1(k206) mutations are amino acid substitutions in the second Calcium binding EGF-like motif (G249E and H251Y, respectively). Thus, they are only separated by one amino acid within the same EGF-like motif. It is surprising that only fbl-1(k206), but not fbl-1(k201), interacts with mig-17 to prolong lifespan. Fibulin-1 is an evolutionarily conserved basement membrane protein that provides structural support to cells and tissues [29]. Fibulin-1 is also known to regulate EGF signaling. Fibulin-1C and D isoforms bind to the EGF receptor, possibly through its EGF-like motifs, and inhibits its activation, localization and function of lung cancer cells [30]. In C. elegans, the LIN-3/EGF and LET-23/EGF receptor signaling promotes healthy aging and longevity [31]. Thus, it might be possible that FBL-1 regulates lifespan by modulating EGF signaling in C. elegans. Among two splicing isoforms, FBL-1C and FBL-1D, FBL-1C is essential for the suppression of mig-17 gonadal defects [8]. It is unknown which isoform acts in the suppression of age-related phenotypes of mig-17. It would be interesting to determine which isoform, or both, is required for the suppression of age-related phenotypes of mig-17 and whether they act in signaling pathways involving EGF.

Supporting information

Percentage of DTC migration defects. Blue and orange bars represent defects in anterior and posterior gonad arms, respectively. Black and red asterisks indicate p-values for Fisher’s exact test against WT and mig-17(k174), respectively p-values for Fisher’s exact test are indicated: ***p < 0.005, *p < 0.05.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Noriko Nakagawa, Nami Okahashi, and Chizu Yoshikata for technical assistance. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to YS(22K20658) and by the Naito Grant for the advancement of natural science to KN. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ewald CY. The Matrisome during Aging and Longevity: A Systems-Level Approach toward Defining Matreotypes Promoting Healthy Aging. Gerontology. 2020;66(3):266–74. Epub 20191213. doi: 10.1159/000504295 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu N, Matsumura H, Kato T, Ichinose S, Takada A, Namiki T, et al. Stem cell competition orchestrates skin homeostasis and ageing. Nature. 2019;568(7752):344–50. Epub 20190403. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1085-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelwick R, Desanlis I, Wheeler GN, Edwards DR. The ADAMTS (A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin motifs) family. Genome Biol. 2015;16:113. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0676-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mead TJ, Apte SS. ADAMTS proteins in human disorders. Matrix Biol. 2018;71–72:225–39. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.06.002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ihara S, Nishiwaki K. Prodomain-dependent tissue targeting of an ADAMTS protease controls cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2007;26(11):2607–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601718 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihara S, Nishiwaki K. Stage-specific activation of MIG-17/ADAMTS controls cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. FEBS J. 2008;275(17):4296–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06573.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishiwaki K, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K. A metalloprotease disintegrin that controls cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2000;288(5474):2205–8. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2205 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubota Y, Kuroki R, Nishiwaki K. A fibulin-1 homolog interacts with an ADAM protease that controls cell migration in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2004;14(22):2011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.10.047 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubota Y, Ohkura K, Tamai KK, Nagata K, Nishiwaki K. MIG-17/ADAMTS controls cell migration by recruiting nidogen to the basement membrane in C. elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(52):20804–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804055106 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imanishi A, Aoki Y, Kakehi M, Mori S, Takano T, Kubota Y, et al. Genetic interactions among ADAMTS metalloproteases and basement membrane molecules in cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0240571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240571 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibata Y, Tanaka Y, Sasakura H, Morioka Y, Sassa T, Fujii S, et al. Endogenous chondroitin extends the lifespan and healthspan in C. elegans. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):4813. Epub 20240227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55417-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiwaki K. Mutations affecting symmetrical migration of distal tip cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1999;152(3):985–97. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.985 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacNeil LT, Watson E, Arda HE, Zhu LJ, Walhout AJ. Diet-induced developmental acceleration independent of TOR and insulin in C. elegans. Cell. 2013;153(1):240–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.049 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi W, Ryu SE, Cheon Y, Park YJ, Kim S, Kim E, et al. A single chemosensory GPCR is required for a concentration-dependent behavioral switching in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2022;32(2):398–411 e4. Epub 20211213. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.11.035 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell JC, Burnaevskiy N, Ma B, Mailig MA, Faust F, Crane M, et al. Electrophysiological Measures of Aging Pharynx Function in C. elegans Reveal Enhanced Organ Functionality in Older, Long-lived Mutants. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1173–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx230 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolanowski MA, Russell RL, Jacobson LA. Quantitative measures of aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. I. Population and longitudinal studies of two behavioral parameters. Mech Ageing Dev. 1981;15(3):279–95. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(81)90136-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shindo T, Kurihara H, Kuno K, Yokoyama H, Wada T, Kurihara Y, et al. ADAMTS-1: a metalloproteinase-disintegrin essential for normal growth, fertility, and organ morphology and function. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(10):1345–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI8635 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enomoto H, Nelson CM, Somerville RP, Mielke K, Dixon LJ, Powell K, et al. Cooperation of two ADAMTS metalloproteases in closure of the mouse palate identifies a requirement for versican proteolysis in regulating palatal mesenchyme proliferation. Development. 2010;137(23):4029–38. doi: 10.1242/dev.050591 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Wu H, Zhang Q, Liu F, Wang J, Wei C, et al. NFKB2 inhibits NRG1 transcription to affect nucleus pulposus cell degeneration and in fl ammation in intervertebral disc degeneration. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021;197:111511. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2021.111511 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Zhang J, Wang B, Chen C, Zhang E, Lv Z, et al. USP24-dependent stabilization of Runx2 recruits a p300/NCOA3 complex to transactivate ADAMTS genes and promote degeneration of intervertebral disc in chronic inflammation mice. Biol Direct. 2023;18(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13062-023-00395-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurses MS, Ural MN, Gulec MA, Akyol O, Akyol S. Pathophysiological Function of ADAMTS Enzymes on Molecular Mechanism of Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2016;7(4):479–90. doi: 10.14336/AD.2016.0111 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundaramoorthy M, Meiyappan M, Todd P, Hudson BG. Crystal structure of NC1 domains. Structural basis for type IV collagen assembly in basement membranes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(34):31142–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201740200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Branyan K, Labelle-Dumais C, Wang X, Hayashi G, Lee B, Peltz Z, et al. Elevated TGFbeta signaling contributes to cerebral small vessel disease in mouse models of Gould syndrome. Matrix Biol. 2023;115:48–70. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2022.11.007 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakrabarti M, Bhattacharya A, Gebere MG, Johnson J, Ayub ZA, Chatzistamou I, et al. Increased TGFbeta1 and SMAD3 Contribute to Age-Related Aortic Valve Calcification. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:770065. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.770065 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw WM, Luo S, Landis J, Ashraf J, Murphy CT. The C. elegans TGF-beta Dauer pathway regulates longevity via insulin signaling. Curr Biol. 2007;17(19):1635–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.058 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cain SA, Woods S, Singh M, Kimber SJ, Baldock C. ADAMTS6 cleaves the large latent TGFbeta complex and increases the mechanotension of cells to activate TGFbeta. Matrix Biol. 2022;114:18–34. Epub 20221108. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2022.11.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mularczyk EJ, Singh M, Godwin ARF, Galli F, Humphreys N, Adamson AD, et al. ADAMTS10-mediated tissue disruption in Weill-Marchesani syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(21):3675–87. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy276 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timpl R, Sasaki T, Kostka G, Chu ML. Fibulins: a versatile family of extracellular matrix proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(6):479–89. doi: 10.1038/nrm1130 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harikrishnan K, Joshi O, Madangirikar S, Balasubramanian N. Cell Derived Matrix Fibulin-1 Associates With Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor to Inhibit Its Activation, Localization and Function in Lung Cancer Calu-1 Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:522. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00522 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwasa H, Yu S, Xue J, Driscoll M. Novel EGF pathway regulators modulate C. elegans healthspan and lifespan via EGF receptor, PLC-gamma, and IP3R activation. Aging Cell. 2010;9(4):490–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00575.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]