Editor—Koning et al report the results of a clinical trial that showed the efficacy of topical fusidic acid as treatment of patients with impetigo.1 This agent has been recommended by the Dutch College of General Practitioners as the treatment of choice in patients with this infection. Koning et al observed that none of the pretreatment isolates of Staphylococcus aureus was resistant to fusidic acid and concluded that many years of use of topical fusidic acid has not resulted in appreciable resistance in staphylococci in the general population.

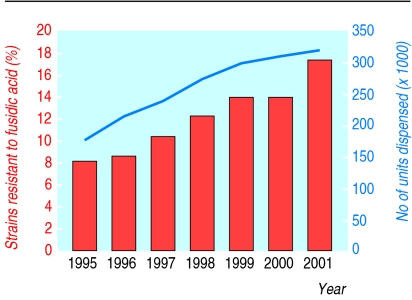

These findings illustrate one of the problems surrounding antimicrobial resistance—namely, that patterns of resistance in one country cannot be extrapolated to those in another. Specifically, data for resistance rates to fusidic acid among S aureus isolates in the United Kingdom differ markedly from those in the Netherlands. In a survey of 28 centres in the United Kingdom the incidence of resistance to fusidic acid among S aureus isolates from the community (excluding strains of methicillin resistant S aureus, which, by their clonal nature, might distort the data) increased from 8.1% in 1995 to 17.3% in 2001 (figure) (R Wise, unpublished data).2 A similar study carried out in Bristol showed an approximately twofold increase in resistance rates (from 6% to 11.5%) among methicillin susceptible S aureus strains isolated between 1998 and 2001.3

The figure also shows that between 1995 and 2001 the number of prescriptions of fusidic acid in the United Kingdom (expressed as total units dispensed and accounted for almost entirely by the topical formulation) nearly doubled (data supplied by Leo Pharmaceuticals).

We cannot explain why the Dutch experience does not mirror our own, although Koning et al have not specified the technique they used to determine the susceptibilities of their isolates, nor have they provided information about the susceptibilities to fusidic acid of any isolates after treatment. A further confounding factor could be the small number of isolates tested (67 strains); evaluating a larger, and therefore more representative, sample might yield a different pattern of resistance.

We do not dispute the efficacy of topical fusidic acid as treatment of patients with impetigo and other superficial skin infections. But fusidic acid is a very valuable drug that is also administered systemically in combination with another antistaphylococcal antibiotic, usually flucloxacillin, as treatment of patients with severe staphylococcal infections. Rates of resistance to this agent among S aureus isolates are increasing in the United Kingdom, directly in line with usage, and we are concerned that further increases in the prescribing of topical fusidic acid will result in even higher levels of resistance. The price of continuing to administer the drug in this way will, in the long term, be the loss of the therapeutic efficacies of both the topical and systemic formulations, and we urge restraint, particularly among general practitioners and dermatologists.

Figure.

Annual rates of resistance to fusidic acid among isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, with numbers of prescriptions for fusidic acid

References

- 1.Koning S, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Nouwen JL, Verduin CM, Bernsen RMD, Oranje AP, et al. Fusidic acid cream in the treatment of impetigo in general practice: double blind randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;324:203–206. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7331.203. . (26 January.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews J, Ashby J, Jevons G, Marshall T, Lines N, Wise R. A comparison of antimicrobial resistance rates in Gram-positive pathogens isolated in the UK from October 1996 to January 1997 and October 1997 to January 1998. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:285–293. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown EM, Thomas P. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lancet 2002;359 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]