SUMMARY

In 2023, the World Health Organization designated eumycetoma causative agents as high-priority pathogens on its list of fungal priority pathogens. Despite this recognition, a comprehensive understanding of these causative agents is lacking, and potential variations in clinical manifestations or therapeutic responses remain unclear. In this review, 12,379 eumycetoma cases were reviewed. In total, 69 different fungal species were identified as causative agents. However, some were only identified once, and there was no supporting evidence that they were indeed present in the grain. Madurella mycetomatis was by far the most commonly reported fungal causative agent. In most studies, identification of the fungus at the species level was based on culture or histology, which was prone to misidentifications. The newly used molecular identification tools identified new causative agents. Clinically, no differences were reported in the appearance of the lesion, but variations in mycetoma grain formation and antifungal susceptibility were observed. Although attempts were made to explore the differences in clinical outcomes based on antifungal susceptibility, the lack of large clinical trials and the inclusion of surgery as standard treatment posed challenges in drawing definitive conclusions. Limited case series suggested that eumycetoma cases caused by Fusarium species were less responsive to treatment than those caused by Madurella mycetomatis. However, further research is imperative for a comprehensive understanding.

KEYWORDS: mycetoma, diagnosis, susceptibility, itraconazole, biofilm, grain, neglected tropical disease, molecular diagnostics

INTRODUCTION

Mycetoma was recognized as a neglected tropical disease in 2016 by the World Health Organization (1). It is a disease with a high morbidity, and it is characterized by large tumorous lesions in the subcutaneous tissue (2). Inside the subcutaneous tissue, the causative agent is embedded in a granule called a grain. Mycetoma can be caused by more than 80 different microorganisms, either of a bacterial or fungal nature (3). Bacterial mycetoma is often named actinomycetoma, while fungal mycetoma is named eumycetoma. In 2023, the fungal pathogens able to cause mycetoma were ranked as high-priority pathogens on the WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide the research, development, and public health action (4). However, it was not clearly stated which fungal species are considered as eumycetoma causative agents. Furthermore, it is currently also not known what are the similarities and differences between these species in terms of pathogenesis and treatment response. Therefore, in this review, we will describe which fungal species are able to cause mycetoma, what the clinical and mycological differences are between these species, and if there are differences in treatment response associated with these pathogens. For this, we have searched the literature using PubMed and included papers from 1945 to 2023.

EUMYCETOMA CAUSATIVE AGENTS

To assess how many eumycetoma causative agents there actually are, we updated the data from references (3, 5, 6) (Table 1). We did this by searching additional papers in the electronic database PubMed from January 2013 to December 2023 on mycetoma. Only case series or case reports presenting novel causative agents were included. The cases presented in these papers were then added to the database. From each paper, the sampling period, the region of sampling, the sex distribution, age distribution, and species isolated were recorded. To determine which fungal species were most prevalent, the total number of cases belonging to a certain species was divided by the total number of fungal causative agents reported and then multiplied by 100 to get the percentage. By adding these cases, the updated database now contained 27,114 mycetoma cases, and for 24,500 cases, it was specified if it was caused by a bacterium or a fungus. The identification of the causative agent differed per study. In some studies, the species were identified based on culture morphology, in others, it was based on histology. Only in a few studies species identification was based on molecular identification. Of those 24,500 mycetoma cases, 12,379 (50.5%) cases were caused by fungi (Table 1). In total, 69 different fungal species were reported to cause eumycetoma. In 86.0% of all eumycetoma cases, the fungus Madurella mycetomatis was the causative agent. The second most common causative agent was Falciformispora senegalensis. This causative agent was encountered in 3.5% of all eumycetoma causative agents (Table 1). We considered a causative agent a common causative agent if it was encountered in ≥10% of independent eumycetoma cases, an occasional causative agent when it was encountered in ≥0.5% of independent eumycetoma cases, and rare if it was encountered in <0.5% of independent eumycetoma cases.

TABLE 1.

Eumycetoma causative species

| Species | No. of isolates | % | Prevalencea | Evidenceb | Color of grains | Size of grains (mm) | Genome sequence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madurella mycetomatis | 10,556 | 85.3 | C | A | Black | Up to 5.0 or more | GCA_001275765.2 GCA_022530565.1 |

(6–98) |

| Falciformispora senegalensis (Syn. Leptosphaeria senegalensis) | 435 | 3.5 | O | A | Black | 0.5–2.0 | (6, 25, 29, 31, 34, 35, 38, 40, 42, 43, 46, 55, 56, 71, 73, 76, 95–102) | |

| Trematosphaeria grisea (Syn. Madurella grisea) | 173 | 1.4 | O | B | Black | 0.3–0.6 | (28, 48, 65, 68, 69, 73–76, 79–82, 85, 88–90, 95–98, 103, 104) | |

| Scedosporium boydii | 120 | 1.0 | O | A | White/white yellow | 0.2–2.0 | GCA_002221725.1 | (6–8, 22, 23, 28, 35, 38, 42, 47–51, 61, 62, 65, 67, 70, 73, 75–77, 79, 80, 84, 85, 87–91, 100, 104) |

| Medicopsis romeroi (Syn. Pyrenochaeta romeroi) | 78 | 0.6 | O/R | B | Black | 0.5–1.5 | (6, 23, 25, 35, 47, 65, 68, 71, 73, 88, 90, 95–97, 105) | |

| Acremonium blochii | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | <1.5 | (67) | |

| Acremonium sclerotigenum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | <1.5 | (26) | |

| Amesia atrobrunnea (Syn. Chaetomium atrobrunneum) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | (99) | ||

| Aspergillus candidus | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | 1.0–2.0 | GCA_002847045.1 | (8, 106) |

| Aspergillus flavus | 14 | 0.1 | R | B | Green/white | GCA_014117465.1 | (61–63, 66, 67, 107–109) | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 4 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_000002655.1 | (6, 8, 61, 62) | |

| Aspergillus nidulans | 12 | <0.1 | R | C | White yellow | <0.6–2 | GCA_000011425.1 | (6, 67, 74, 105, 110–114) |

| Aspergillus niger | 3 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | GCA_000002855.2 | (26, 63) | |

| Aspergillus sydowii | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | GCA_001890705.1 | (115) | |

| Aspergillus terreus | 2 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_000149615.1 | (62, 67) | |

| Aspergillus ustus | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | GCA_000812125.1 | (84) | ||

| Cladophialophora bantiana | 4 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5 | GCA_000835475.1 | (90, 116, 117) |

| Cladophialophora mycetomatis | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5 | (90) | |

| Cladosporium ramotellenum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | (26) | |||

| Corynespora cassiicola | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | <1.0 | GCA_022059125.1 | (118) |

| Curvularia geniculata | 4 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5–1.0 | GCA_016162275.1 | (119–121) |

| Curvularia lunata | 8 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5–1.0 | GCA_005212705.1 | (6, 35, 67, 97, 122, 123) |

| Diaporthe phaseolorum (Syn. Phomopsis phaseoli) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Yellow | (124) | ||

| Emarellia grisea | 6 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.3–0.6 | (95, 96) | |

| Emarellia paragrisea | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.3–0.6 | (95) | |

| Exophiala dermatitidis | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5–1.0 | (84) | |

| Exophiala jeanselmei | 25 | 0.2 | R | A | Black | 0.5–1.0 | (6, 61, 65, 67, 72, 75, 77, 79, 97, 100, 125–134) | |

| Exophiala oligosperma | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5–1.0 | GCA_000835515.1 | (84) |

| Exserohilum rostratum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | GCA_026367775.1 | (135) | ||

| Falciformispora lignatilis | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | (136) | ||

| Falciformispora tompkinsii (Syn. Leptosphaeria tompkinsii) | 11 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | 0.5–1.0 | (60, 95–99, 137–139) | |

| Fusarium falciforme (Syn. Neocosmospora falciformis) | 8 | <0.1 | R | A | White | 0.2–0.5 | GCA_026873545.1 | (6, 8, 20, 69, 78, 99, 140) |

| Fusarium verticillioides (Syn. Fusarium monoliforme) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | 0.5 | GCA_000149555.1 | (141) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_013085055.1 | (142) | |

| Fusarium solani (Syn Neocosmospora solani) | 18 | 0.1 | R | C | White | <1.5 | GCA_020744495.1 | (6, 42, 62, 67, 125, 143–148) |

| Fusarium chlamydosporum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Zwart | <1.5 | GCA_014898915.1 | (149) |

| Fusarium incarnatum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_004367075.1 | (67) | |

| Fusarium subglutinans | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | GCA_013396075.1 | (150) | ||

| Fusarium thapsinum | 2 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_013186935.1 | (99) | |

| Geotrichum candidum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | GCA_013365045.1 | (8) | ||

| Ilyonectria destructans (Syn. Cylindrocarpon destructans) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | 0.5 | GCA_020740775.1 | (151) |

| Macroventuria anomochaeta | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | GCA_010093625.1 | (26) | ||

| Madurella fahalii | 9 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | GCA_029876055.1 | (26, 96, 99, 152–154) | |

| Madurella pseudomycetomatis | 13 | 0.1 | R | C | Black | (13, (84, 91, 99, 154–156) | ||

| Madurella tropicana | 3 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | (13, (99, 154) | ||

| Microascus gracilis | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | (157) | ||

| Microsporum audouini | 6 | <0.1 | R | C | White | (6, 22, 31) | ||

| Microsporum canis | 4 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_000151145.1 | (158–161) | |

| Neocosomospora cyanescens (Syn. Cylindrocarpon cyanescens) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | (162) | ||

| Neoscytalidium dimidiatum (Syn. Scytalidium dimidiatum) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Brown | 4.0 | GCA_900092665.1 | (66) |

| Neotestudina rosatii | 14 | 0.1 | R | C | White | <0.5–1.5 | (6, 23, 77, 99, 105, 163) | |

| Nigrograna mackinnonii (syn. Pyrenochaeta mackinnonii) | 21 | 0.2 | R | C | Black | 0.3–1.0 | GCA_001007845.1 | (91, 95–98, 164, 165) |

| Paecilomyces variotii | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_004022145.1 | (166) | |

| Penicillium thomii | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | (26) | |||

| Phaeoacremonium krajdenii | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | (167) | ||

| Phaeoacremonium parasiticum | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | (168) | ||

| Phialophora verrucosa | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | GCA_002099365.1 | (169) | |

| Phomopsis longicola | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | GCA_000800745.1 | (104) | ||

| Pleurostoma ochraceum (Syn. Pleurostomophora ochracea) | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | Yellow | (170) | ||

| Pseudochaetosphaeronema larense | 2 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | (96) | ||

| Rhinocladiella atrovirens | 2 | <0.1 | R | C | (38, 100) | |||

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | 5 | <0.1 | R | C | Black | GCA_000467735.1 | (95–97) | |

| Sarocladium kiliense (Syn. Acremonium kiliense) | 7 | <0.1 | R | C | White yellow | <1.5 | GCA_030734395.1 | (67, 80) |

| Subramaniula obscura | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | (26) | |||

| Subramaniula thielavioides | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | (26) | |||

| Trichophyton interdigitale | 1 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_019359935.1 | (26) | |

| Trichophyton rubrum | 2 | <0.1 | R | C | White | GCA_000151425.1 | (54, 171) | |

| Xenoacremonium recifei (Syn. Acremonium recifei) | 2 | <0.1 | R | C | White yellow | <1.5 | GCA_012184525.1 | (172) |

| Fungi without species identification | 772 | 6.2 |

C, common (>5% of the reported cases worldwide were caused by this species); O, occasional (caused 1%–5%); and R, rare (caused <1%).

A, strong evidence (microorganism was encountered in more than 50 individual cases, and its ability to form a mycetoma grain was confirmed in in vivo animal models); B, moderate evidence (microorganism was encountered in more than 10 individual cases, and its presence within the grain was confirmed by either immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization); C, marginal evidence (microorganism was encountered in less than 10 individual cases, and there was no additional evidence that could demonstrate that the fungus that grew out of the grain was also present in the grain in the tissue)

As many of the eumycetoma causative agents are also considered fungi that live freely in the environment or are known to live on the skin, there has been a debate over whether all these can be considered true eumycetoma causative agents. Especially, for those species that can be found in large quantities in the environment, there has been a debate about whether these would be true eumycetoma causative agents or contaminants. Most of the eumycetoma causative agents have long culture times, while Aspergillus and Fusarium species, in general, grow rapidly under laboratory conditions. Therefore, for this review, we also created an evidence-based score, ranging from strong (A) to moderate (B) to marginal (C). Strong evidence was considered when Koch’s postulates were adhered to, meaning that a microorganism was encountered in more than 50 individual cases, and its ability to form a mycetoma grain was confirmed in in vivo animal models. An example of a species that belonged to this category was M. mycetomatis, as its grain-forming potential was confirmed in several animal models (173–176). Moderate evidence was considered when a microorganism was encountered in more than 10 individual cases, and its presence within the grain was confirmed by either immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization. An example of a species that belonged to this category was Aspergillus flavus because in one case study with Aspergillus-specific antibodies, its presence was demonstrated in the eumycetoma grain in tissue (107). Marginal evidence was considered when a microorganism was encountered in less than 10 individual cases, and there was no additional evidence that could demonstrate that the fungus that grew out of the grain was also present in the grain in the tissue. As can be seen in Table 1, for M. mycetomatis, F. senegalensis, and Scedosporium bodyii, the evidence was strong. For most of the rare causative agents, the evidence was less strong, and the color of the grain was not even known.

Since in most of the studies, identification was based on either culture or histology, misidentifications could have occurred. The ranking presented is likely to shift when molecular identification of eumycetoma causative agents becomes the main identification technique. The study of Borman et al. demonstrated that 28 out of the 31 Trematosphaeria grisea isolates from the British National Collection of Pathogenic Fungi and French Institut Pasteur Culture Collection were in fact other black grain mycetoma causative agents, namely Nigrograna mackinnonii (n = 8), Medicopsis romeroi (n = 10), Rhytidhysteron rufulum (n = 4), Emarellia grisea (n = 5), and Emarellia paragrisea (n = 1) when they were re-identified using sequencing (95). The same was noted in Mexico, where, again, after sequencing, three isolates previously identified as T. grisea appeared to be N. mackinnonii and two isolates previously identified as M. mycetomatis were, in fact, Madurella pseudomycetomatis (164, 177). Therefore, etiologies might differ from what was reported before, and it could be that when molecular identification becomes the standard identification technique, differences in the ranking will be noted. However, as seen in a study in the Mycetoma Research Centre, in some regions, when molecular identification is introduced, the diversity in causative agents might enhance, but M. mycetomatis will remain by far the most common causative agent of eumycetoma (178).

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE CAUSATIVE AGENTS

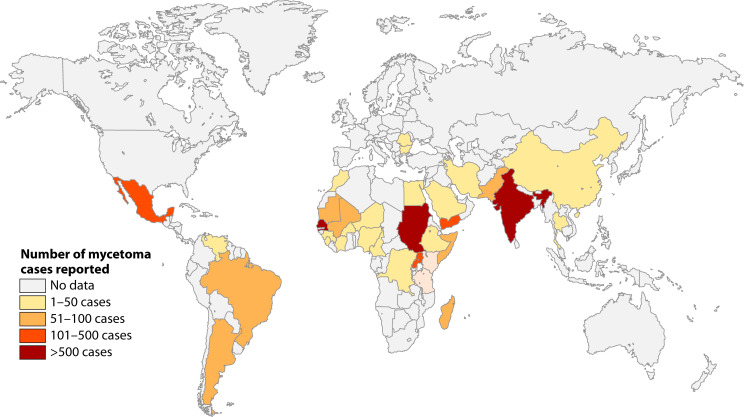

Eumycetoma has been reported from 102 countries, but there are large regional differences in the number of cases reported (179). If we look at eumycetoma alone, the highest number of cases was reported from Sudan (3, 5, 179), Senegal, and India (3, 5, 6, 179) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Number of eumycetoma cases reported based on the metadata used for publications (3, 5) using references (6–94).

Due to the lack of surveillance programs, the prevalence of eumycetoma is largely unknown. In a previous report, the prevalence was calculated based on the number of reported cases divided by the population of the country in a particular year. In that way, a prevalence of 1.8 per 100,000 was obtained for Sudan (5). However, in surveys performed in highly endemic villages in Sudan, a prevalence of 1–5.2 eumycetoma cases per 1,000 inhabitants was found in the 1960s (180) and 6.2–35 cases per 1,000 inhabitants in the 2010s (180, 181), indicating that the prevalence of eumycetoma is much higher than reported.

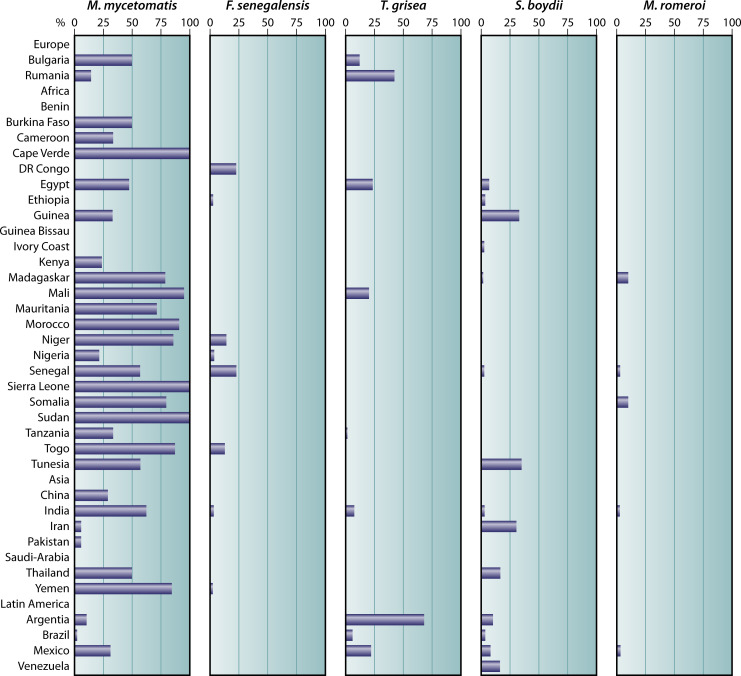

In the villages surveyed in Sudan, the most prevalent causative agent of eumycetoma was M. mycetomatis. In general, M. mycetomatis is the most common causative agent of eumycetoma in most regions in the world. However, the prevalence of F. senegalensis, T. grisea, Scedosporium boydii, and M. romeroi varies per region (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Distribution of the most common causative eumycetoma agents per country. For each country, the percentage of M. mycetomatis, F. senegalensis, T. grisea, S. boydii, and M. romeroi were calculated by the following formula (number of cases per selected species/total number of eumycetoma cases reported in that country × 100) and displayed in the corresponding panels.

F. senegalensis is mainly found in Western Africa and T. grisea in Europe and Latin America. S. boydii is also more prevalent in temperate regions in Europe and North America.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

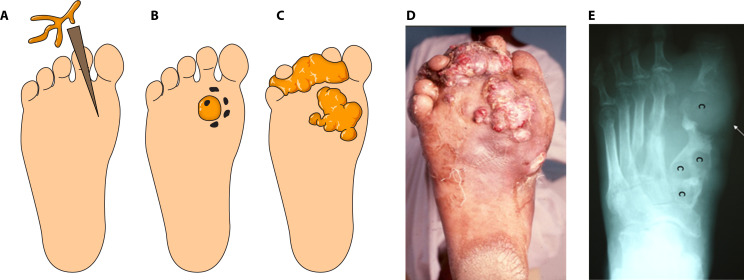

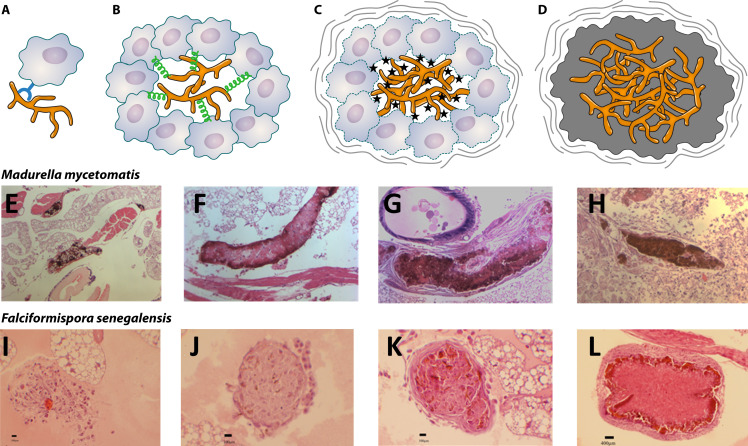

Since there are so many different causative agents able to cause mycetoma, one wonders if there are also differences in the clinical presentation per causative agent. Eumycetoma is an implantation mycosis and, therefore, there are several stages in which a eumycetoma lesion develops (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Eumycetoma development. (A) The fungal causative agent is introduced into the subcutaneous tissue via a minor trauma such as a thorn prick. (B) Inside the tissue, the fungus will form a grain. (C) Subcutaneous nodules will form, which will further extend into the subcutaneous tissue. (D) Picture of a mycetoma lesion in real life. (E) The eumycetoma causative agents will invade the bone and cavities (c) will form.

Phase 1: implantation into the subcutaneous tissue

As can be noted from Table 1, most of the eumycetoma causative agents are fungal species that can be found everywhere in our surroundings (S. boydii, Aspergillus species, and Fusarium species), and patients could have acquired from everywhere. Furthermore, these fungi have also been implicated in invasive fungal infections, and only a small portion of patients infected with these fungi develop mycetoma. DNA from the more specific eumycetoma causative agents, such as M. mycetomatis, F. senegalensis, and Falciformispora tompkinsii, was found in soil, thorns, spines, dung, and even in the walls of houses in highly endemic regions (135, 182–185). However, in those studies, it was impossible to culture the fungi from these sources too. In earlier studies, M. mycetomatis was cultured from soil and anthills (186, 187), and F. senegalensis and F. tompkinsii were cultured from about 50% of the examined dry thorns of Acacia trees (188, 189). However, their identity was not confirmed by sequencing.

A penetrating trauma is needed to introduce the causative agent into the subcutaneous tissue. This can be a prick from a thorn, splinter, or fish scale, a cut from a knife or farm implement, or insect and snake bites (180). These penetrating traumas often heal quickly, without any discomfort for the patient but they will result in the introduction of the causative agent in the subcutaneous tissue.

Phase 2: grain formation

Once into the subcutaneous tissue, the fungus will organize itself in a grain. The time of grain formation within the human host is unknown, as subclinical cases of eumycetoma have never been described. However, all grains generally originate within a single lesion from a single isolate introduced into the subcutaneous tissue (190).

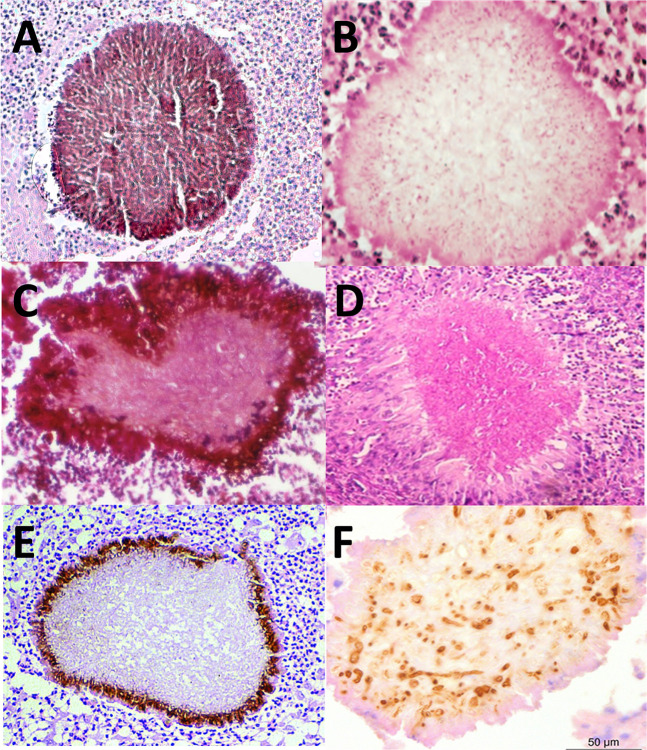

Grains are considered a unique feature of mycetoma, and each species forms its own type of grain (94). The majority of eumycetoma causative agents either produce black or white grains, but the less common causative agents Pleurostoma ochraceum and Aspergillus flavus have been reported to form either yellow or green grains, respectively (Table 1) (170). With histology, clear differences between the grains can be noted.

As shown in Fig. 4, the three black grains all differ and have species-specific features. In all cases, the color of the black grain is caused by melanin, a high molecular weight compound that is anchored to extracellular proteins. M. mycetomatis produces this melanin through the DHN-, DOPA-, and pyomelanin pathways (191, 192). In the M. mycetomatis grain, the hyphae are embedded in a brown matrix material, which is called cement. This cement material comprises areas of amorphous electron-dense material and areas of membrane-bound vesicular inclusions (193). Within this cement material, DNA and proteins of the host and pathogen can be found (194–197). In fact, 99.3% of the DNA and proteins identified in these grains is from humans, only 0.069% from the fungus (194, 198, 199). In M. mycetomatis grains, this cement material is found throughout the grain. Collagen in the grain shows a disintegration of the cross-striations with fiber swelling (200). The collagen appears honeycombed rather than branched (200). Within the hyphae, numerous concentric layers of cell wall material were often noted, indicative of intra-hyphal growth (193).

Fig 4.

Histology of grains. (A) M. mycetomatis; (B) S. boydii picture reprinted from reference (201) with permission of the publisher (McGraw Hill); (C) F. senegalensis, picture reprinted from reference (202); (D) Fusarium, picture reprinted from reference (203) with permission of the publisher (copyright 2016 Blackwell Verlag GmbH); (E) T. grisea, picture reprinted from reference (204) with permission; (F) A. flavus, stained with antibodies against Aspergillus, picture reprinted from reference (107) with permission of the publisher (copyright 2015 Blackwell Verlag GmbH).

The grains of the three Falciformispora species (Fig. 4C) that cause mycetoma are indistinguishable from each other (205) and difficult to distinguish from the grains of T. grisea (Fig. 4E) (193) or M. romeroi (200). At the periphery of these grains, the hyphae are embedded in a black, cement-like substance. In the centrum of the grain, a loose network of hyphae is noted. This portion is non-pigmented (205, 206). The grains of T. grisea resemble those of F. senegalensis and also have a blackish-brown cement-like material at the periphery of the grain. The hyphae in the center of the grain are weakly pigmented (193, 205, 206).

The white grains of Scedosporium and Fusarium species can be histopathologically similar (207). No cement material was noted in the white grains formed by S. boydii and Fusarium species (208). Instead, the central portion of each grain often consists of loosely interwoven hyaline or colorless hyphae (209). Thickening of the fungal cell walls and fusion of the cell walls were noted (208). Widespread cytoplasmic disorganization was noted. With electron microscopy, mitochondria were no longer noted, and increased granularity of the cytoplasm and an increase in the number of intracytoplasmic membranes were noted (208).

The grains described in patients are generally mature, and the early steps of grain formation in humans are unknown. Since grains cannot be formed in vitro, the process of grain formation can only be studied in in vivo grain models developed in the larvae of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella and mice (173, 174, 210–212). Only for M. mycetomatis, F. senegalensis, S. boydii, Exophiala jeanselmei, and Fusarium falciforme, in vivo grain models have been developed (173, 174, 210–212). For S. boydii, E. jeanselmei, and F. falciforme, only models in mice have been developed, while for M. mycetomatis, grain models exist in mice and in the invertebrate Galleria mellonella, and for F. senegalensis, only a model in G. mellonella has been published (173, 174, 210–212). The grains formed in these animal modes all resembled the grains formed in humans.

In the two G. mellonella models, grain formation was followed in more detail over time. For both species, the process of grain formation can be divided into four stages (Fig. 5). In the first stage, hyphae cluster together and are surrounded by host cells (194). In the second stage, the hyphae are in close contact, and cement material starts to form. Individual host cells are still found between the hyphae, and melanization can also be seen. In the third stage, the cement material is fully formed, and individual host cells are no longer noted between the hyphae. A capsule is found to surround the grain (194). In the fourth stage, a massive influx of host cells is noted, and the granuloma forms, which surrounds the mature grain (194). When comparing the different grain-forming stages between M. mycetomatis and F. senegalensis in the invertebrate G. mellonella, it seems that the same stages are noted, but the timing is different. For instance, cement material already formed within 4 hours in the grain when G. mellonella larvae were infected with M. mycetomatis. When larvae were infected with F. senegalensis this was delayed (Fig. 5) (210).

Fig 5.

Grain formation over time. (A) Fungal cells are recognized by the host via pathogen receptor proteins. (B) Hemocytes will then agglutinate around the fungal hyphae, and host cells will be cross-linked to each other and attach to the fungal cells. The fungal cells will excrete zincophores and siderophores to obtain nutrients. (C) Degranulation of the host cells will occur, and reactive oxygen species will be produced. In order to protect itself, the fungus will produce melanin and trehalose. The host will form a capsule surrounding the granuloma. (D) In the final stage, the fungus will completely disintegrate the host cells and form the cement material. The extracellular matrix will be melanized. Although the steps in grain formation are similar between M. mycetomatis and F. senegalensis, the timing is not. (E) A M. mycetomatis grain in G. mellonella 4 hours after infection. Cement material is forming. (F) A M. mycetomatis grain in G. mellonella 24 hours after infection. Cement material is formed, and only a few host cells are still found within the grain. (G) A mature M. mycetomatis grain in G. mellonella larvae after 3 days. At this time no host cells are present in the cement material. The cement material is melanized, and a capsule surrounds the grain. (H) A massive influx of immune cells toward the M. mycetomatis grains 7 days after infection. (I) No grain is present in G. mellonella larvae infected with F. senegalensis 4 hours after infection. Only loose hyphae are noted. (J) At 24 hours after infection, the first signs of grain formation are noted. There is no cement material yet, and melanization is not noted. (K) F. senegalensis grain at 3 days after infection, cement material is forming, and some melanization of the grain is noted. Also, a capsule is forming. (L) At 7 days after infection, a mature F. senegalensis grain in G. mellonella is noted. Panels A–D are based on reference (194), panels E–H are reprinted from reference (174) (published under a Creative Commons license), and panels I–L are reprinted from reference (213) (published under a Creative Commons license).

In M. mycetomatis, proteomic and transcriptomic analyses have been performed to gain insight into the processes leading to grain formation. Up- and downregulation of genes and proteins at 4, 24, 72 h, and 7 days after infection were mapped (194, 199). The analysis of these responses led to the formation of a theoretical model for M. mycetomatis grain formation in G. mellonella (194) (Fig. 5A through D). In this model, grain formation starts with the recognition of M. mycetomatis by the host via pathogen recognition proteins. In G. mellonella, these receptors are β-glucan-recognizing proteins and hemolin (194). In turn, M. mycetomatis increases vesicle transport to transport building blocks for the extracellular matrix through the cell wall. Adhesion proteins, such as fructose bisphosphate aldolase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and enolase, are displayed on the surface allowing M. mycetomatis to attach itself to the host (194). Next, hemocytes will agglutinate around the fungal hyphae, and the production of G. mellonella defense protein Hdd11 is increased, resulting in cross-linking of the hemocytes and attaching to M. mycetomatis. M. mycetomatis will subsequently secrete a zincophore to acquire zinc and siderophores to acquire iron and cross-link the extracellular matrix (194, 199). The cytoplasm of the G. mellonella hemocytes will be discharged, and degranulation occurs, which elevates reactive oxygen species production and the secretion of antimicrobial peptides in the grain (194). Finally, melanin will be produced by the fungus, and a capsule is formed surrounding the grain. In that stage, no hemocytes are found anymore within the grain; they are all lysed, and the extracellular matrix is completely melanized (194, 199). The melanin is most likely both intracellular entrapped in the fungal cell wall and extracellular entrapped into the extracellular matrix. Which of these processes are unique for the M. mycetomatis grain formation or shared within the grain formation of other fungal species is currently unknown; however, it is expected that melanization will be only found in black grain eumycetoma grain formation.

Phase 3: formation of the subcutaneous swelling

Despite the large number of causative agents and the differences in grain formation, the clinical presentation of eumycetoma is almost indistinguishable, and there are no clear differences noted between the different causative agents. The disease usually starts with the formation of a nodule. They are typically painless but painful in 18%–20% of patients, caused by secondary bacterial infection in most of them (214). The swelling is usually firm and rounded, but it may be soft, lobulated, and rarely cystic (214). It is often mobile. As the swelling increases, the skin becomes stretched and attached to the swelling. Localized areas of hyperhidrosis and sweating are occasionally seen in the affected skin (215). After some time, the swelling can suppurate and drain through sinus tracts (214). Prior to discharge, pustules may be visible (214). Secondary nodules evolve. Sinuses can close after discharge during the active phase of the disease, and new adjacent sinuses may open while some of the old ones may heal completely (214). These sinuses are numerous and interconnected with each other. They discharge serous, sero-purulent fluid and can be pussy with secondary bacterial infection. During the active phase of the disease, the sinuses discharge grains (214).

Although the foot is the most commonly affected region of the body, eumycetoma can also develop at other body sites, and no part is exempted. The foot (68.7%) and hand (4.0%) are affected most (5). Extrapedal involvement in the chest, abdominal walls, perineum, eye, gluteal and perineal regions, head, and neck occurs but is relatively rare (5). Mycetoma at these rare sites has high morbidity, is difficult to treat, and can be fatal (216). Furthermore, spreading from the primary site can occur via the blood and the lymphatics (2).

Phase 4: invasion of the bone

When the lesion progresses, the bone may be infected. Initially, the bone is displaced, bowed, or compressed from one or both sites (217). Then, an irritation reaction at the bone surface is noted (217). This can be noted on an X-ray by a periosteal reaction or diffuse reactive sclerosis (217). In the next stage, the fungus penetrates the periosteum and cortex and forms cavities in the bone. Cavitation is initially limited to a solitary bone and then spreads either longitudinally in the bone or horizontally toward other bones (217). Whether there are characteristic differences in bone affection or the appearance of the cavities between fungal species is currently unknown.

DIAGNOSIS AND IDENTIFICATION OF THE FUNGAL PATHOGENS

In order to identify the fungal pathogen, a surgical biopsy or a fine needle aspiration is used to obtain tissue specimens in which grains are present. The biopsy should be checked visually for the presence of grains before it is sent to the laboratory. In the laboratory, tissue materials are divided and submitted for microbiology, histopathology, and when available molecular examination. Tissue biopsies without visible grains usually result in negative cultures (193).

Histology

As mentioned earlier, eumycetoma grains are often either black or white, and there are some characteristic features that can be used to differentiate the causative agents (Fig. 4). The first is, of course, the presence of melanin; this would already differentiate the black (Fig. 4A, C, and E ) from the white grains (Fig. 4B and D). The second is the presence of cement material. The cement material is found throughout the grain in M. mycetomatis (Fig. 4A), but in the black grains of F. senegalensis (Fig. 4C) and T. grisea (Fig. 4E), the center is often non-pigmented, and cement material is absent (193). Of the 750 grains identified as M. mycetomatis by culture, 714 were also identified by histopathology, resulting in a sensitivity of 95.2% and a specificity of 95.4% (218). However, when molecular identification was used as a comparator, the sensitivity still remained at 93.8%, but the specificity dropped to 42.8%, simply because many of the black grains were wrongfully identified as M. mycetomatis in histology while they were in fact other black grain causative agents (178). The average time to identification was 8.5 (range: 2–15) days (178).

Culture

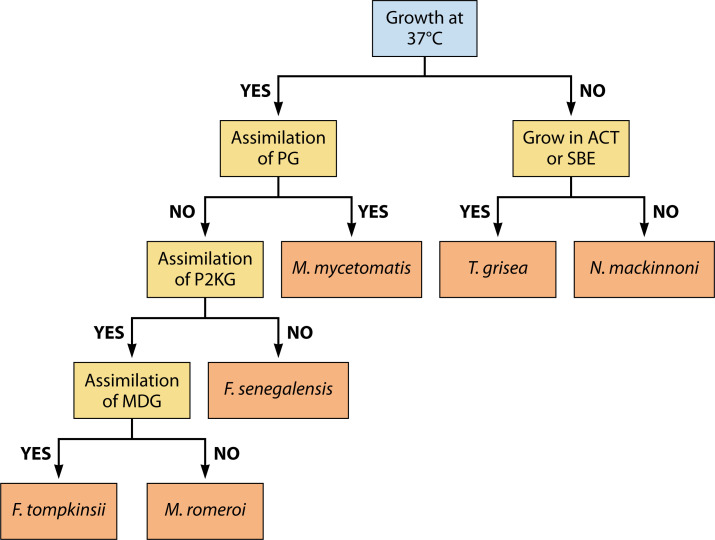

In order to culture the causative agents, grains are usually washed several times in sterile saline, crushed with a sterile glass rod, and plated onto Sabouraud agar plates supplemented with antibiotics. Commonly used antibiotics are gentamicin sulfate (400 mg/mL), penicillin G (20 U/mL), streptomycin (40 mg/mL), or chloramphenicol (50 mg/mL) (193). Plates are often inoculated in duplicate to be able to incubate them at 25°C and 37°C, as not all causative agents are able to grow at 37°C on culture medium. The average time to identification was 21.2 days (range: 2.5–60 days) (178). Identification is mainly based on the colony morphology and the microscopic morphology of the fruiting bodies, if present (Table 2)(193). For species such as M. mycetomatis, it can be difficult to identify the causative agent at the species level, as colony morphologies can be quite diverse, and sporulation is usually not observed. Also, differentiation between T. grisea and M. romeroi is difficult as their colony morphologies are quite similar. In most cases, T. grisea is sterile; however, some isolates are known to produce abortive flask-shaped fruiting bodies bearing conidia like those formed by M. romeroi (193).

TABLE 2.

Growth characteristics of the common and occasional causative agents of eumycetomaa

| Colony morphology | Ascospores | Conidia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Color (obverse) | Color (reverse) | Secreted pigment | Texture | Growth at 37°C | Absent | Conidiophore | Shape | Size |

| M. mycetomatis | Yellowish brown to gray | Yellowish brown to gray | Yes | Skin like | Yes | Absent | Phialides with minute conidia | Globose to rounded | 2 × 3 µm |

| F. senegalensis | Gray-black | Black | No | Velvet | Yes | Subhyaline, obovoidal to ellipsoidal 23–36 × 8.0–13.5 µm, 4-septate | Absent | Absent | |

| Trematosphaeria grisea | Gray, becoming faint toward the margin | Dark gray | No | Velvet | No | Absent | Ampulliform phialides | Ellipsoidal to bacilliform | 2.5–4.0 × 1.3–1.5 µm |

| M. romeroi | Gray, becoming faint toward the margin | Dark gray | No | Velvet | No | Absent | Ampulliform phialides | Ellipsoidal to bacilliform | 2.5–4.0 × 1.3–1.5 µm |

| Scedosporium boydii | White gray, becoming darker gray or brown | Dark brown or gray, almost black | No | Downy to cottony | Yes | Absent | On branched cylindrical conidiophores or solitary | Globose to subglobose, thick-walled | 4–9 × 6–10 µm |

To differentiate the most common black-grain causative agents, one can make use of an identification scheme based on assimilation patterns (Fig. 6)

Fig 6.

Identification of causative agents by growth characteristics. Assimilation of or growth on potassium gluconate (PG), potassium 2-keto-gluconate (P2KG), methyl-D-glucopyranoside (MDG), actidione (ACT), or L-sorbose can help in differentiating the most common causative agents of black grain mycetoma. Adapted from references (94, 220).

Identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Identification of isolates can also occur via matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. For this, isolates are cultured on Sabouraud agar and then proteins are extracted by sequential ethanol, 70% formic acid, and acetonitrile precipitation and then applied to the target plate and overlaid with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix and measured (96). In the current Version MALDI Biotyper database of Brüker, 222 fungal species are included, including the rare eumycetoma causative agents Acremonium sclerotigenum, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus sydowii, Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus ustus, Exophiala dermatitidis, Fusarium chlamydosporum, Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium solani, Fusarium verticillioides, Microsascus gracilis, Neoscytalidum dimidiatum, and Sarocladium kiliense (221). For some eumycetoma causative agents, the Büker database only identifies to a species complex such as Aspergillus flavus/oryzae group, the Microsporium audouinii/canis group, and the Trichophyton rubrum group, or the genus level, such as Scedosporium and Curvularia species (221). For the more common eumycetoma causative agents, several labs have built their own databases so that they could identify the more common eumycetoma causative agents, such as Madurella mycetomatis, Falciformispora senegalensis, Trematosphaeria grisea, Scedosporium boydii, and Medicospsis romeroi to the species level (96, 222, 223). Furthermore, these databases also included samples of Curvularia lunata, Emarellia grisea, Emarellia paragrisea, Exophiala jeanselmei, Exserohilum rostratum, Madurella fahalii, Nigrograna mackinnonii, and Rhytidhysteron rufulum (96, 222).

Molecular identification

When DNA is extracted directly from grains, the time to identification can be reduced to 2.8 (range: 2.4–3.1) hours (178). In order to isolate DNA directly from grains, bead beating with metal beads is performed, after which a standard DNA isolation kit can be used. To identify the common and occasional causative agents and several rare eumycetoma causative agents, some specific amplification techniques have been developed. For the common and occasional causative agents, the amplification techniques are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Primers and probes for the identification of the common and occasional causative agents of eumycetoma

| Species | Primer/probe name | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madurella mycetomatis | 26.1a | 5′-AATGAGTTGGGCTTTAACGG-3′ | (224) |

| 28.3a | 5′-TCCCGGTAGTGTAGTGTCCCT-3′ | (224) | |

| mm-fw | 5′-TCTCCTGTCCTACGACATCTGTGG-3′ | (225) | |

| mm-rv | 5′-TTCCTCACCTCCCAGCCCTTT-3′ | (225) | |

| PF2-specific-Myc | 5’-TGACCGTCGGCGTCTCTT-3’ | (226) | |

| R2-specific-Myc | 5′-TAGGCTGTCAGAAAACACATCG-3′ | (226) | |

| PF3-Myc | 5'-CTCCCGGTAGTGTAGTGT-3’ | (226) | |

| R3-Myc | 5'-CAGAAGACTCAGAGAGGCC-3’ | (226) | |

| M.m_forward | 5′-CCTCCCGGTAGTGTAGTGTCC-3′ | (227) | |

| M.m_reverse | 5′-GAGAGGCCGTACAGAGCAAAT-3′ | (227) | |

| M.m_probe | 5′-FAM-GGCGTCCGCCGGAGGATTATACAAC-BHQ1-3′ | (227) | |

| Falciformispora senegalensis | F.s_forward | 5′-GTTCCTACGCCGGCAAC-3′ | (227) |

| F.s_reverse | 5′-AGACAGGTATACTGCTTTTGCTGC-3′ | (227) | |

| F.s_probe | 5′-HEX- GCCGCTGGGTCTCCACC-BHQ1-3′ | (227) | |

| Scedosporium boydii | Forward | 5′-TGGCGAGCACGGTCTTG-3′ | (228) |

| Reverse | 5′-ACATTCACGGCAGACACTGATT-3′ | (228) | |

| Apioboy_P | 5'-FAM-TAGCAACGGAGTGTACGGAACCACCC-BBQ-3’ | (228) |

For the other causative agents, amplification of the internally transcribed spacer region (ITS) with either primers V9G (5′-TTACGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTA-3′) and LS266 (5′-GCATTCCCAAACAACTCGACTC-3′), ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) and ITS5 (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′), or ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) and ITS3 (5′GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC-3′) is used, followed by sanger sequencing or rolling circle amplification (RCA) with species-specific probes (229, 230) (Table 4). For most causative agents, each of the three primer sets for the ITS regions can be used; however, in the study of Desnos-Ollivier (97), four M. mycetomatis strains could not be amplified with the V9D and LS266 or the ITS4 and ITS5 primers. In the studies where amplification was performed directly on grains, in general, the pan-fungal primers ITS4 and ITS5 or the M. mycetomatis-specific primers 26.1A and 28.3A were used (13, 99).

TABLE 4.

Rolling circle amplification for the identification of eumycetoma causative agentsa

| Species | Primer/probe name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| RCA1 | 5′-ATGGGCACCGAAGAAGCA-3′ | |

| RCA2 | 5′-CGCGCAGACACGATA-3′ | |

| M. mycetomatis | MYC | 5′p-ACTACACTACCGGGAGGCCCgatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCATtaccggtgcggatagctac CGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaAGGGGGCCGAGGGAC-3′ |

| F. senegalensis | FSEN | 5′p-ACATAGACAAGGGTGTTGCCGGCgatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCATtaccggtgcggatagctac CGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaCAACGTACGGTAC-3′ |

| T. grisea | TGRIS | 5′p-ACCCGTAGGTCCTCCCAAAAGCGgatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCATtaccggtgcggatagctac CGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaTGGACGCCAGTCC-3′ |

| S. boydii | BoyRCA | 5′p-GGGTCGCGAAGACTCGCCGTAgatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCATtaccggtgcggatagctac CGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaTTTCAGGGCCTACGGA |

| S. apiospermum | ApioRCA | 5′p-CATCGTCCTCTTYTCAGAGGGGgatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCATtaccggtgcggatagctac CGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaCCGGCGGGAGGGG |

| M. romeroi | MRO | 5′p-AAGGCGAGTCCACGCACTCTGGgatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCATtaccggtgcggatagctac CGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaCTGCCAATGACTTT-3′ |

TREATMENT AND IN VITRO SUSCEPTIBILITY OF THE PATHOGENS

The standard treatment of eumycetoma is combination therapy with either an azole or terbinafine and surgery (231). In a survey by the WHO held in 2022, it appeared that 85% of the respondents use itraconazole to treat eumycetoma (125, 232, 233). This was followed by terbinafine (48%), voriconazole (41%), and posaconazole (33%). Voriconazole and posaconazole were used mainly in high-income countries (125, 232, 233). There is only one double-blind clinical trial performed for eumycetoma. That is, trial NCT03086226, Proof-of-Concept Superiority Trial of Fosravuconazole Versus Itraconazole for Eumycetoma in Sudan (234). In that trial, only cases of M. mycetomatis mycetoma were included, which were either treated with itraconazole or fosravuconazole, the prodrug of ravuconazole. Therefore, no comparison can be made if eumycetoma cases where other fungi were the causative agent will respond similarly to the treatment given. Therefore, due to the lack of clinical trials, we can only review in vitro susceptibility data, animal models, and case series and estimate if there are likely differences in treatment response between different causative agents. Future clinical trials should be performed to be able to answer this question properly.

In vitro susceptibility data

The in vitro susceptibility data for the different eumycetoma causative agents were all generated with the protocols from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) or the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (235). These were either in-house assays (236–242) or using the commercial YeastOne testing panel (242–244). For some of the non-sporulating causative agents, such as Madurella species, a small adaptation to these protocols was needed to perform in vitro susceptibility testing with hyphal fragments instead of conidia (235). These adaptations were recently reviewed and will not be discussed here (235).

In Table 5, the published in vitro susceptibilities toward the antifungal agents commonly used to treat mycetoma are listed, as well as those for ravuconazole. When we focus on the common and occasional causative agents of eumycetoma, we can already see some clear differences. For itraconazole, the concentration that will inhibit 90% of all tested isolates in growth (MIC90) is 0.25 μg/ml for M. mycetomatis and 1 μg/ml F. senegalensis, which are lower than the serum levels that are usually attained with this drug. For T. grisea, S. boydii, and M. romeroi, the MIC90 is above these serum levels, indicating that these three species most likely will not be inhibited in growth in a lesion (245, 235). Also, for some of the more rare causative agents, such as the Fusarium species and M. fahalii, higher MIC90s for itraconazole are noted. The high MIC found in M. fahalli was most likely due to the insertion of glutamic acid at position 149 and a shift from isoleucine to valine at position 153 of the CYP51 protein (152). For the newer azoles, voriconazole and posaconazole, T. grisea and M. romeroi seem to be more susceptible as their MIC90s were within range of the serum levels. However, for most Fusarium species, also for voriconazole, posaconazole, and terbinafine, high MIC90s were obtained (245).

TABLE 5.

In vitro susceptibilities of eumycetoma causative agents as determined by the CLSI methodology

| Itraconazole | Ravuconazole | Posaconazole | Voriconazole | Terbinafine | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Occurrence | N | MIC90 (μg/ml)a | Range (μg/ml) | Ref | N | MIC90 (μg/ml)a | Range (μg/ml) | Ref | N | MIC90 (μg/ml)a | Range | Ref | N | MIC90 (μg/ml)a | Range (μg/ml) | Ref | N | MIC90 (μg/ml)a | Range (μg/ml) | Ref |

| Madurella mycetomatis | C | 131 | 0.25 | <0.008–1 | (246) | 131 | 0.032 | <0.002–0.125 | (246) | 34 | 0.064 | <0.03–0.125 | (240) | 34 | 0.25 | <0.016–0.5 | (242) | 34 | 16 | 2–> 16 | (240) |

| Falciformispora senegalensis | O | 6 | 1 | 0.03–1 | (235) | 6 | 0.25 | 0.064–0.25 | (247) | 4 | 0.125 | 0.03–1 | (235) | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | (235) | 3 | 0.25 | 0.125–0.25 | (235) |

| Trematosphaeria grisea | O | 11 | 4 | 0.125–4 | (235) | 4 | 8 | 0.125–8 | (247) | 3 | 0.25 | 0.016–0.25 | (235) | 3 | 0.25 | 0.125–0.25 | (235) | ||||

| Scedosporium boydii | O | 39 | >4 | >4 | (248) | 30 | 4 | 0.5–16 | (249) | 48 | 2 | 0.125–16 | (250) | 39 | 1 | 0.125–16 | (248) | 30 | >16 | >16 | (249) |

| Medicopsis romeroi | O/R | 23 | >8 | 1- > 8 | (95, 235) | 6 | 1 | 0.25–1 | (247) | 5 | 1 | 0.25–1 | 23 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (95, 235) | |||||

| Acremonium blochii | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Acremonium sclerotigenum | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Amesia atrobrunnea | R | 4 | 0.07 | 0.04–0.07 | (251) | 7 | 0.25 | 0.06–0.25 | (251) | 7 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (251) | ||||||||

| Aspergillus candidus | R | 3 | 0.25 | 0.03–0.25 | (252) | 3 | 1 | 0.05–1 | (252) | ||||||||||||

| Aspergillus flavus | R | 175 | 1 | 0.125–1 | (250) | 13 | 1 | 0.125–1 | (253) | 175 | 0.5 | 0.06–1 | (250) | 175 | 1 | 0.125–2 | (250) | ||||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | R | 1,263 | 1 | 0.125- > 8 | (250) | 114 | 0.5 | 0.25–4 | (253) | 1,263 | 0.5 | 0.03–4 | (250) | 1,263 | 0.5 | 0.06- > 8 | (250) | 82 | 2 | 0.05–4 | (254) |

| Aspergillus nidulans | R | 38 | 1 | 0.125–1 | (250) | 38 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (250) | 38 | 0.25 | 0.03–0.5 | (250) | ||||||||

| Aspergillus niger | R | 174 | 2 | 0.125–4 | (250) | 22 | 2 | 0.5–4 | (253) | 174 | 1 | 0.06–1 | (250) | 174 | 1 | 0.03–2 | (250) | ||||

| Aspergillus sydowii | R | 23 | 2 | 0.5–2 | (250) | 9 | 2 | 0.125–2 | (253) | 23 | 1 | 0.25–1 | (250) | 23 | 1 | 0.06–2 | (250) | ||||

| Aspergillus terreus | R | 75 | 1 | 0.125–1 | (250) | 8 | 0.5 | 0.25–0.5 | (253) | 75 | 0.5 | 0.125–1 | (250) | 75 | 0.5 | 0.125–2 | (250) | ||||

| Aspergillus ustus | R | 11 | 4 | 2–4 | (255) | 3 | 1 | 0.25–1 | (256) | 3 | 16 | 4–16 | (256) | 11 | 8 | 0.25–8 | (255) | 11 | 0.5 | 0.06–5 | (255) |

| Cladophialophora bantiana | R | 37 | 0.125 | <0.016–0.25 | (257) | 37 | 0.125 | <0.016–0.125 | (257) | 37 | 2 | 0.125–4 | (257) | ||||||||

| Cladophialophora mycetomatis | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladosporium ramotellenum | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Corynespora cassiicola | R | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | (258) | ||||||||||

| Curvularia geniculata | R | 14 | 0.25 | 0.06–1 | (259) | 14 | 0.25 | <0.03–0.5 | (259) | 14 | 1 | 0.125–4 | (259) | ||||||||

| Curvularia lunata | R | 10 | 0.25 | 0.125– > 16 | (259) | 10 | 0.25 | <0.03–0.5 | (259) | 10 | 1 | 0.25–1 | (259) | ||||||||

| Diaporthe phaseolorum | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Emarellia grisea | R | 5 | 0.5 | 0.06–0.5 | (95) | 5 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (95) | ||||||||||||

| Emarellia paragrisea | R | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | (95) | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | (95) | ||||||||||||

| Exophiala dermatitidis | R | 51 | 2 | <0.015–2 | (260) | 51 | 2 | <0.03–2 | (260) | 51 | 2 | 0.06–2 | (260) | 51 | 4 | <0.03–4 | (260) | ||||

| Exophiala jeanselmei | R | 17 | 0.25 | 0.016–0.25 | (235) | 17 | 0.06 | 0.016–0.06 | (235) | 17 | 0.5 | 0.125–2 | (235) | ||||||||

| Exophiala oligosperma | R | 4 | 8 | 0.06–8 | (261) | 2 | 0.06 | <0.03–0.06 | (261) | 5 | 8 | 0.125–8 | (261) | ||||||||

| Exserohilum rostratum | R | 34 | 0.03 | <0.03–0.125 | (262) | 34 | 0.03 | <0.03–0.125 | (262) | 34 | 0.25 | <0.03–1 | (262) | 34 | 0.03 | <0.03–0.03 | (262) | ||||

| Falciformispora lignatilis | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Falciformispora tompkinsii | R | 3 | 0.25 | 0.25 | (235) | 3 | 0.25 | 0.25 | (235) | 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | (235) | ||||||||

| Fusarium falciforme | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fusarium verticillioides | R | 13 | 16 | 1–16 | (245) | 13 | 16 | 2–16 | (245) | 13 | 16 | 0.25–16 | (245) | 13 | 16 | 1–16 | (245) | 13 | 32 | 1–32 | (245) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | R | 14 | 16 | 1–16 | (245) | 14 | 16 | 1–16 | (245) | 14 | 16 | 0.06–16 | (245) | 14 | 16 | 0.5–16 | (245) | 14 | 32 | 0.5–32 | (245) |

| Fusarium solani | R | 22 | 16 | 16 | (245) | 22 | 16 | 4–16 | (245) | 22 | 16 | 16 | (245) | 22 | 16 | 4–16 | (245) | 22 | 32 | 16–32 | (245) |

| Fusarium chlamydosporum | R | 4 | 50 | 12.5–50 | (263) | ||||||||||||||||

| Fusarium incarnatum | R | 1 | >8 | >8 | (264) | 1 | 8 | 8 | (264) | ||||||||||||

| Fusarium subglutinans | R | 1 | >16 | >16 | (150) | 1 | >16 | >16 | (150) | 1 | 2 | 2 | (150) | ||||||||

| Fusarium thapsinum | R | 5 | >16 | >16 | (265) | 5 | >16 | 8–>16 | (265) | 5 | >16 | >16 | (265) | 5 | 4 | 2–4 | (265) | 5 | 0.5 | 0.25–0.5 | (265) |

| Geotrichum candidum | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ilyonectria destructans | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Macroventuria anomochaeta | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Madurella fahalii | R | 1 | >16 | >16 | (235) | 2 | 0.016 | 0.004–0.016 | (247) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (235) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (235) | ||||

| Madurella pseudomycetomatis | R | 7 | 0.06 | 0.016–0.06 | (235) | 6 | 0.032 | 0.008–0.032 | (247) | 7 | 0.06 | 0.008–0.06 | (235) | 7 | 0.25 | 0.008–0.25 | (235) | ||||

| Madurella tropicana | R | 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | (235) | 3 | 0.064 | 0.016–0.064 | (247) | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | (235) | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | (235) | ||||

| Microascus gracilis | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Microsporum audouini | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Microsporum canis | R | 100 | 4 | 0.03–8 | (266) | 42 | 0.06 | <0.03–0.25 | (267) | 100 | 1 | 0.08–2 | (266) | 100 | 0.06 | 0.08–0.5 | (266) | 100 | 0.25 | 0.08–0.5 | (266) |

| Neocosomospora cyanescens | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Neoscytalidium dimidiatum | R | 17 | >16 | <0.03- > 16 | (268) | 17 | 2 | 0.125–2 | (268) | 17 | 0.25 | <0.03–0.5 | (268) | 17 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (268) | ||||

| Neotestudina rosatii | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nigrograna mackinnonii | R | 10 | 2 | (0.25–2) | (95) | 10 | 1 | 0.125–1 | (95) | ||||||||||||

| Paecilomyces variotii | R | 26 | 0.25 | 0.016–0.5 | (269) | 26 | 16 | 0.016–16 | (269) | 26 | 0.125 | 0.016–0.5 | (269) | 26 | 16 | 0.03–16 | (269) | 26 | 4 | 0.125–32 | (269) |

| Penicillium thomii | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Phaeoacremonium krajdenii | R | 11 | 16 | 16–>16 | (270) | 11 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (270) | 11 | 0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | (270) | ||||||||

| Phaeoacremonium parasiticum | R | 16 | >16 | >16 | (270) | 16 | 1 | 0.25–1 | (270) | 16 | 1 | 0.25–1 | (270) | ||||||||

| Phialophora verrucosa | R | 46 | 2 | 0.25–4 | (271) | 46 | 0.5 | 0.03–1 | (271) | 46 | 1 | 0.06–4 | (271) | 46 | 0.25 | 0.002–1 | (271) | ||||

| Phomopsis longicola | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pleurostoma ochraceum | R | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | (170) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (170) | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | (170) | ||||||||

| Pseudochaetosphaeronema larense | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhinocladiella atrovirens | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | R | 2 | 1 | 0.5–1 | (95) | 2 | 0.25 | 0.125–0.25 | (95) | ||||||||||||

| Sarocladium kiliense | R | 4 | >16 | >16 | (272) | 4 | >16 | 4–>16 | (272) | 4 | 1 | 0.5–1 | (272) | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | (272) | ||||

| Subramaniula obscura | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Subramaniula thielavioides | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Trichophyton interdigitale | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Trichophyton rubrum | R | 111 | 2 | 0.03–16 | (273) | 16 | 0.125 | 0.03–0.125 | (274) | 111 | 0.5 | 0.016–1 | (273) | 111 | 0.125 | 0.03–16 | (273) | 111 | 0.06 | 0.008–0.06 | (273) |

| Xenoacremonium recifei | R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Serum level | >1–2 | >0.5–1.5 | >1–6 | 2.8 | |||||||||||||||||

The MIC90 values above the therapeutic goal according to reference (275) are bold and underlined, the MIC90 values equal to the upper boundary of the therapeutic goal according to reference (275) are in bold, and the MIC90 values lower than the upper boundary of the therapeutic goal according to reference (275) are in normal font.

Although in vitro susceptibility assays can determine if a drug is active against fungal hyphae, this does not always predict if the drug is also active in a more complex structure such as a grain. Only in one study, the MIC of hyphae was compared to the MIC obtained from grains. In this study, the grains were obtained from experimentally infected mice, not humans (276). The MIC obtained with M. mycetomatis hyphae was 1 µg/mL, while grains were not inhibited by concentrations up to 100 µg/mL (276). The same phenomenon was also noted for Exophiala dermatitidis biofilms (277). E. dermatitidis planktonic cells were susceptible to itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole, while the E. dermatitidis biofilm was completely resistant (277, 278). This demonstrates that the cement material present in biofilms and grains can protect the hyphae inside these structures against antifungal agents (235, 277). As previously mentioned, this cement material consists of melanin, proteins, chitin, and polysaccharides. M. mycetomatis melanin was able to bind ketoconazole and itraconazole, and when 250 µg/mL M. mycetomatis melanin was added to an in vitro susceptibility assay, a strong rise in MIC was noted for ketoconazole and itraconazole (191). The polysaccharide β-1,3-D-glucan and extracellular DNA are also known to bind antifungal agents (235).

So, based on the in vitro data generated so far, one can conclude that the different causative agents have different susceptibilities toward the standard drugs used to treat eumycetoma patients. Furthermore, the cement material also seems to protect the fungus inside against these drugs.

Evidence from animal models

Although animal models were developed for M. mycetomatis, F. senegalensis, S. boydii, E. jeanselmei, and F. falciforme (173, 174, 210–212), only in the models for M. mycetomatis and F. senegalensis, antifungal treatments were evaluated. If we look at the two G. mellonella models for M. mycetomatis and F. senegalensis, we see a difference in clinical response toward antifungal agents. In these models, larvae are infected with either M. mycetomatis or F. senegalensis and then treated at 4, 28, and 52 h after infection with either 1 mg amphotericin B/kg of body weight/day, 5.7 mg itraconazole/kg of body weight/day, or 7.14 mg terbinafine/kg of body weight/day (213, 279). Prolonged larval survival was noted when M. mycetomatis-infected larvae were treated with either amphotericin B or terbinafine, not when they were treated with itraconazole (279). For F. senegalensis-infected larvae, prolonged survival was only noted when they were treated with amphotericin B, not when treated with terbinafine or itraconazole (213). A similar comparison could not be made for the studies performed in mouse models, as only in the M. mycetomatis mouse model treatment responses were measured, not in the other mouse models. The treatment response measured in mice infected with M. mycetomatis was similar to that in G. mellonella larvae infected with M. mycetomatis, although the read-out was different. No grains were observed at day 21 in mice infected with M. mycetomatis and treated with 1 mg amphotericin B/kg of body weight/day for 14 days, while grains were still present at day 21 when mice were treated with 40 mg itraconazole/kg of body weight/day for 14 days (280). So, based on the scarce data from animal models, it looks like there is a difference in treatment response between the different species; however, much more data are needed.

Evidence from case series

The most extensive case series of eumycetoma patients treated with either ketoconazole or itraconazole are from the Mycetoma Research Centre (MRC) in Khartoum, Sudan (281, 282), followed by the Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, Senegal (42) (Table 6). In the Sudanese studies, more than 1,500 eumycetoma cases were followed (281, 282). In all patients, the causative agent was identified as M. mycetomatis, and adjusted cure rates of 56.2% and 67.6% were noted for ketoconazole and itraconazole (Table 6). Furthermore, a complete cure was significantly associated with surgery, smaller lesion sizes, and shorter disease duration (281, 282). In the Senegalese study, the black grain causative agents were not always identified to the species level; however, a better treatment outcome was noted when itraconazole was combined with surgery (adjusted cure rate of 100%) and a comparable treatment outcome when terbinafine was combined with surgery (adjusted cure rate of 55.6%). Also, this study noted an association with better treatment outcomes when medical treatment was combined with surgery (42). Unfortunately, no large cohort studies were performed for the other causative agents, and only a few case series and case reports have been described. For the other occasional eumycetoma causative agents Falciformispora species (136–138, 233), T. grisea (103, 283–285), and S. boydii (286), as well as for the rare Fusarium causative agents (140), corrected treatment responses toward the azoles ranged from 20% to 38.5% and again antifungal treatment combined with surgery had a more favorable outcome. However, the number of cases was small. Strikingly, the corrected treatment responses of in vitro azole-resistant Fusarium species, T. grisea, and S. boydii were much lower than those found in the larger studies of M. mycetomatis. But clearly, more data are needed to indicate whether there is a correlation between the species and treatment outcome.

TABLE 6.

Treatment response as described in case series

| Species | N | Treatment | Surgery (including amputation) | Treatment response | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cured | Still on treatment | Amputation | Not cured or recurrenceb | Lost to follow up | Corrected cure ratea (%) | |||||

| Madurella mycetomatis | 13 | Ketoconazole (100–400 mg/day) | Unknown | 4 (30.8%) | 9 (69.2%) | 30.8 | (287) | |||

| Madurella mycetomatis | 1,242 | Ketoconazole (400–800 mg/day) | 1,242 | 321 (25.8%) | 35 (2.8%) | 215 (17.3) | 671 (54.0%) | 56.2 | (281) | |

| Madurella mycetomatis | 11 | Itraconazole (400 mg/day) | 0 | 1 (9.1%) | 10 (90.9%) | 9.1 | (288) | |||

| Madurella mycetomatis | 377 | Itraconazole (400 mg/day) | 164 | 48 (12.7%) | 306 (81.2) | 23 (6.1) | 13 | 67.6 | (282) | |

| Madurella mycetomatis or Falciformispora senegalensis | 23 | Itraconazole | 23 | 23 (100%) | 100.0 | (42) | ||||

| Madurella mycetomatis or Falciformispora senegalensis | 68 | Terbinafine (500 mg BID) | 49 | 20 (29.4) | 32 | 18 | 2 | 14 | 55.6 | (42) |

| Falciformispora species | 4 | Azoles | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (50%) | 25 | (136–138, 233) | ||

| Trematosphaeria grisea | 5 | Azoles | 1 | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | 20 | (103, 283–285) | |||

| Scedosporium species | 3 | Azoles | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3) | (286) | |||

| Fusarium species | 19 | Azoles | 6 (31.6%) | 5 (26.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | 7 (36.8%) |

6 (31.6%) | 38.5 | (140) | |

For the corrected cure rate, only those patients who had completed their treatment and were not lost to follow-up were included. For that, we used the following calculation: (number of cured patients)/[(total number of patients) − (number of patients under treatment) − (number of patients lost to follow-up)] × 100.

Not cured also includes patients who improved on treatment as they were still not cured.

PREVENTION OF EUMYCETOMA

There are currently no thorough studies performed on the prevention of eumycetoma. However, in the past decade, several modeling studies showed that, in Sudan, the strongest predictors of mycetoma occurrence were aridity, proximity to water, low soil calcium and sodium concentrations, and the distribution of various thorny trees species such as Acacia trees (181, 289–291). Also, most patients seem to live on light clay soil (181, 291). Next to that, a correlation between eumycetoma and close contact with stock animals, such as goats and cows, was noted (292–294). This correlation is most likely due to the environmental conditions associated with cattle. Animal enclosures are often found to be made of thorns, and they often stand in mud, dirt, and dung (294). Also, ticks and other insects are found on these animals, and in one of these ticks M. mycetomatis was detected by PCR (295). Although there are no large case-cohort studies performed yet, it seems clear that improving the living and hygienic standards in mycetoma-endemic regions and villages could help to reduce the risk of contracting eumycetoma (291). Also, wearing shoes might lower the risk of contracting eumycetoma; however, so far, no studies have been performed to prove this assumption.

WAY FORWARD

So, from the in vitro and in vivo comparisons, there is some evidence that not all causative agents respond the same to therapy, but the numbers are small. To enhance the current knowledge, gathering information from individual cases and comparing their treatment response are important. To be able to do that, a few things are needed. First, a proper diagnosis and species identification are needed. This means that more reliable methods need to be used for species identification. So far, the most reliable method was molecular identification; however, species-specific molecular identification tools have been developed for only a few causative agents. The development of more identification tools, which will help diagnose and update the epidemiologic data, is on its way. Second, more data are needed to assess and compare the treatment responses of the different causative agents to standard treatment to develop proper treatment guidelines. In the open-source drug discovery project MycetOS (https://github.com/OpenSourceMycetoma/General-Start-Here), in vitro responses against new drugs are already determined against multiple causative agents so that at least the differences in in vitro susceptibility can be assessed. To assess the differences in treatment responses in patients, the new initiative to collect case reports from implantation mycoses in the openly accessible, publicly-funded CURE ID platform (https://cure.ncats.io) is another step forward (232). These collected case reports can then be analyzed to gain insights into the treatment responses of the different causative agents, which in turn can be further developed into treatment guidelines as a resource for treating physicians.

CONCLUSION

This review established that M. mycetomatis was the most common causative agent of eumycetoma, followed by F. senegalensis, T. grisea, S. boydii, and M. romeroi. Clinically, there were no differences reported on the form of the lesions or the bone involvement between the different causative agents, but the differences in grain morphology and formation were noted. Only for M. mycetomatis and S. boydii species-specific molecular diagnostic tools were available, but for the other causative agents, they are currently being developed. Differences in in vitro susceptibility and treatment responses in animal models and patient series were noted, but the numbers were small. Therefore, there is a large need to gather more case series with proper species identification in order to develop treatment guidelines that also take the causative agent of eumycetoma into account. This is desperately needed to improve the therapeutic outcome in this difficult-to-treat neglected tropical disease.

Biographies

Wendy van de Sande is an associate professor in medical mycology at ErasmusMC, the Netherlands. She has been studying mycetoma since 2001 and obtained her PhD from Erasmus University in Rotterdam in 2007 cumlaude. She published 128 peer-reviewed papers on mycetoma. She and her team developed several diagnostic tools to identify the causative agents at the species level. These tools are currently used worldwide. She also leads the biological screening in the Mycetoma Open Source drug discovery program MycetOS. She is a founding member of the global mycetoma working group, convener of the eumycetoma working group at the International Society of Human and Animal Mycoses and vice chair of the skinNTD subgroup of the Diagnostic Technical Advisory Group of the World Health Organization.

Prof. Ahmed Fahal, a distinguished surgeon and professor, has significantly contributed to medical research, education, and the management of mycetoma. Trained at the University of Khartoum and in the UK, he attained the position of consultant surgeon at Soba University Hospital and a professorship at the University of Khartoum. He excels in mycetoma and tropical surgery, founding the globally recognized Mycetoma Research Centre at the University of Khartoum, WHO Collaborating Center on Mycetoma and Skin NTDs. His extensive research, with over 300 peer-reviewed articles, positions him among the top 2% of global scientists. Playing fundamental roles in educational development and scientific research agencies, he currently serves as the Vice President of the Arab Scientific Research Councils Federation. Prof. Fahal's enduring legacy encompasses groundbreaking clinical trials, the establishment of mycetoma satellite centers, and vocational training for mycetoma patients, reflecting his dedication to comprehensive healthcare. His numerous awards underscore his outstanding achievements in scientific innovation and research.

Contributor Information

Wendy W. J. van de Sande, Email: w.vandesande@erasmusmc.nl.

Graeme N. Forrest, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Rod Hay, The International Foundation for Dermatology, London, United Kingdom.

Ferry Hagen, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . 2016. WHA69.21: assessing the burden of mycetoma. WHO, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WWJ, Welsh O, Mahgoub ES, Goodfellow M, Fahal AH. 2016. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis 16:100–112. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00359-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van de Sande W, Fahal A, Ahmed SA, Serrano JA, Bonifaz A, Zijlstra E, eumycetoma working group . 2018. Closing the mycetoma knowledge gap. Med Mycol 56:153–164. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO . 2023. WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action

- 5. van de Sande WWJ. 2013. Global burden of human mycetoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7:e2550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oladele RO, Ly F, Sow D, Akinkugbe AO, Ocansey BK, Fahal AH, van de Sande WWJ. 2021. Mycetoma in West Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 115:328–336. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trab032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balabanoff VA. 1980. Mycetomas originated from South-East Bulgaria (author's transl). Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 55:605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Avram A. 1966. A study of mycetomas of rumania. Mycopathol Mycol Appl 28:1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02276016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abbott P. 1956. Mycetoma in the Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 50:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(56)90004-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lynch JB. 1964. Mycetoma in the Sudan. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 35:319–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fahal AH, Sabaa AHA. 2010. Mycetoma in children in Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 104:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fahal A, Mahgoub ES, El Hassan AM, Jacoub AO, Hassan D. 2015. Head and neck mycetoma: the mycetoma research centre experience. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahmed EA, Nour BYM, Abakar AD, Hamid S, Mohamadani AA, Daffalla M, Mahmoud M, Altayb HN, Desnos-Ollivier M, de Hoog S, Ahmed SA. 2020. The genus Madurella: molecular identification and epidemiology in Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14:e0008420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mohamed ESW, Bakhiet SM, El Nour M, Suliman SH, El Amin HM, Fahal AH. 2021. Surgery in mycetoma-endemic villages: unique experience. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 115:320–323. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hassan R, Deribe K, Fahal AH, Newport M, Bakhiet S. 2021. Clinical epidemiological characteristics of mycetoma in eastern Sennar locality, Sennar state, Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15:e0009847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siddig EE, Ahmed A, Hassan OB, Bakhiet SM, Verbon A, Fahal AH, van de Sande WWJ. 2023. Using a Madurella mycetomatis-specific PCR on grains obtained via non-invasive fine-needle aspirated material is more accurate than cytology. Mycoses 66:477–482. doi: 10.1111/myc.13572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abate DA, Ayele MH, Mohammed AB. 2021. Subcutaneous mycoses in Ethiopia: a retrospective study in a single dermatology center. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 115:1468–1470. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trab080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tilahun Zewdu F, Getahun Abdela S, Takarinda KC, Kamau EM, Van Griensven J, Van Henten S. 2022. Mycetoma patients in Ethiopia: case series from Boru Meda hospital. J Infect Dev Ctries 16:41S–44S. doi: 10.3855/jidc.16047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Enbiale W, Bekele A, Manaye N, Seife F, Kebede Z, Gebremeskel F, van Griensven J. 2023. Subcutaneous mycoses: endemic but neglected among the neglected tropical diseases in Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 17:e0011363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson AM. 1965. The aetiology of mycetoma in Uganda compared with other African countries. East Afr Med J 42:182–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kwizera R, Bongomin F, Meya DB, Denning DW, Fahal AH, Lukande R. 2020. Mycetoma in Uganda: a neglected tropical disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14:e0008240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vanbreuseghem R. 1958. Epidemiologie et therapeutique des pieds de Madura au Congo belge. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 51:759–814. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Destombes P, Mariat F, Rosati L, Segretain G. 1977. Mycetoma in Somalia - results of a survey done from 1959 to 1964. Acta Trop 34:355–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Destombes P, Du Tour J, Marquet J, Mariat F, Segretain G. 1958. Les mycétomes en Côte Française des Somalis. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 51:575–581. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Orio J, Destombes P, Mariat F, Segretain G. 1963. Mycetoma in the French Somali coast. Review of 50 cases observed between 1954 and 1962. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 56:161–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Colom MF, Ferrer C, Ekai JL, Ferrández D, Ramírez L, Gómez-Sánchez N, Leting S, Hernández C. 2023. First report on mycetoma in Turkana County-North-Western Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 17:e0011327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mavura D, Chapa P, Sabushimike D, Kini L, Hay R. 2021. Mycetoma in Moshi, Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 115:340–342. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agarwal SC, Mathur DR. 1985. Mycetoma in northern Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med 37:133–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahe A, Develoux M, Lienhardt C, Keita S, Bobin P. 1996. Mycetomas in Mali: causative agents and geographic distribution. Am J Trop Med Hyg 54:77–79. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Traore T, Toure L, Diassana M, Niang M, Ballo E, S Coulibaly B, Hans-Moevi A. 2021. Prise en charge medico-chirurgicale des mycetomes a l'hopital Somine Dolo de Mopti (Mali). Med Trop Sante Int 1:mtsi.2021.170. doi: 10.48327/mtsi.2021.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Philippon M, Larroque D, Ravisse P. 1992. Mycetoma in Mauritania: species found, epidemiologic characteristics and country distribution. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 85:107–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kébé M, Ba O, Mohamed Abderahmane MA, Mohamed Baba ND, Ball M, Fahal A. 2021. A study of 87 mycetoma patients seen at three health facilities in Nouakchott, Mauritania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 115:315–319. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bourrel P, Cerutti J, Disy P, Olivier R. 1974. Les mycetomas propos de 64 observations. Méd Trop 34:221–247. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Klueken N, Camain R, Baylet M, Basset A. 1965. Epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment of mycetoma in Western Africa. Hautarzt 16:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rey M, Baylet R, Camain R. 1962. Donnees actuelles sur les mycetomes. A propos de 214 cas africains. Ann Derm Syph 89:511–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ndiaye B, Develoux M, Langlade MA, Kane A. 1994. Actinomycotic mycetoma. Apropos of 27 cases in Dakar; medical treatment with cotrimoxazole. Ann Dermatol Venereol 121:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dieng MT, Niang SO, Diop B, Ndiaye B. 2005. Actinomycetomas in Senegal: study of 90 cases. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 98:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dieng MT, Sy MH, Diop BM, Niang SO, Ndiaye B. 2003. Mycetoma: 130 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol 130:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sarr L, Niane MM, Diémé CB, Diatta BA, Coulibaly NF, Dembélé B, Diouf AB, Kinkpé CAV, Sané AD, Ndiaye A, Seye SIL. 2016. Chirurgie des mycetomes fongiques a grain noir. A propos de 44 patients pris en charge a l'Hopital Aristide le Dantec de Dakar (Senegal) de decembre 2008 a mars 2013. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 109:8–12. doi: 10.1007/s13149-015-0463-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Diadie S, Ndiaye M, Diop K, Diongue K, Diouf J, Sarr M, Sarr L, Ly F, Dieng MT, Niang SO. 2022. Extrapodal mycetomas in Senegal: epidemiologica, clinical and etiological study of 82 cases diagnoses from 2000 to 2020. Med Trop Sante Int 2:1–8. doi: 10.48327/mtsi.v2i1.2022.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Badiane AS, Ndiaye M, Diongue K, Diallo MA, Seck MC, Ndiaye D. 2020. Geographical distribution of mycetoma cases in Senegal over a period of 18 years. Mycoses 63:250–256. doi: 10.1111/myc.13037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sow D, Ndiaye M, Sarr L, Kanté MD, Ly F, Dioussé P, Faye BT, Gaye AM, Sokhna C, Ranque S, Faye B. 2020. Mycetoma epidemiology, diagnosis management, and outcome in three hospital centres in Senegal from 2008 to 2018. PLoS One 15:e0231871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Develoux M, Audoin J, Treguer J, Vetter JM, Warter A, Cenac A. 1988. Mycetoma in the Republic of Niger: clinical features and epidemiology. Am J Trop Med Hyg 38:386–390. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gamet A, Brottes H, Essomba R. 1964. New cases of mycetoma detected in Cameroun. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 57:1191–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pitche P, Napo-Koura G, Kpodzro K, Tchangaï-Wallam K. 1999. Les mycetomes au Togo: aspects épidémiologiques et étiologiques de cas histologiquement diagnostiqués. Med Afr Noire 46:322–325. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Darré T, Saka B, Mouhari-Toure A, Tchaou M, Dorkenoo AM, Doh K, Walla A, Amégbor K, Pitché VP, Napo-Koura G. 2018. Mycetoma in the togolese: an update from a single-center experience. Mycopathologia 183:961–965. doi: 10.1007/s11046-018-0260-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Coulanges P, Vicens R, Rakotonirina-Randriambeloma PJ. 1987. Mycetomas in Madagascar (apropos of 142 cases seen in the laboratory of anatomical pathology of the Pasteur Institute of Madagascar from 1954 to 1984. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar 53:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]