Abstract

Background

The energy/protein imbalance in a low-protein diet induces lipid metabolism disorders in late-phase laying hens. Reducing energy levels in the low-protein diet to adjust the energy-to-protein ratio may improve fat deposition, but this also decreases the laying performance of hens. This study investigated the mechanism by which different energy levels in the low-protein diet influences liver lipid metabolism in late-phase laying hens through the enterohepatic axis to guide feed optimization and nutrition strategies. A total of 288 laying hens were randomly allocated to the normal-energy and normal-protein diet group (positive control: CK) or 1 of 3 groups: low-energy and low-protein diet (LL), normal-energy and low-protein diet (NL), and high-energy and low-protein diet (HL) groups. The energy-to-protein ratios of the CK, LL, NL, and HL diets were 0.67, 0.74, 0.77, and 0.80, respectively.

Results

Compared with the CK group, egg quality deteriorated with increasing energy intake in late-phase laying hens fed low-protein diet. Hens fed LL, NL, and HL diets had significantly higher triglyceride, total cholesterol, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and fatty acid synthase levels, but significantly lower hepatic lipase levels compared with the CK group. Liver transcriptome sequencing revealed that genes involved in fatty acid beta-oxidation (ACOX1, HADHA, EHHADH, and ACAA1) were downregulated, whereas genes related to fatty acid synthesis (SCD, FASN, and ACACA) were upregulated in LL group compared with the CK group. Comparison of the cecal microbiome showed that in hens fed an LL diet, Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio were enriched, whereas riboflavin metabolism was suppressed. Cecal metabolites that were most significantly affected by the LL diet included several vitamins, such as riboflavin (vitamin B2), pantethine (vitamin B5 derivative), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and 4-pyridoxic acid.

Conclusion

A lipid metabolism disorder due to deficiencies of vitamin B2 and pantethine originating from the metabolism of the cecal microbiome may be the underlying reason for fat accumulation in the liver of late-phase laying hens fed an LL diet. Based on the present study, we propose that targeting vitamin B2 and pantethine (vitamin B5 derivative) might be an effective strategy for improving lipid metabolism in late-phase laying hens fed a low-protein diet.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40104-024-01055-y.

Keywords: Cecal microbiome, Energy/protein imbalance, Late-phase laying hens laying hens, Liver lipid metabolism, Low-protein diet, Multi-omics

Background

With an increase in living standards, the demand for food quality has also increased. Owing to the high nutritional value of eggs, laying hen breeding has become a rapidly expanding area in the poultry farming industry [1]. Although modern, highly intensive breeding methods for laying hens have improved breeding efficiency, convenience, and effectiveness, these methods also reduce the activity of laying hens, resulting in excessive energy intake that is converted into fat deposition in the liver, leading to fatty liver, stress, and increased mortality [2, 3]. The late-phase laying hens are particularly prone to lipid metabolism disorders after experiencing peak production, which may lead to fat accumulation in the liver, reduced egg production quality, increased mortality, and ultimately, economic losses [4].

A low-protein (LP) poultry diet is valuable due to several advantages including lower feed costs, reduced industry dependence on dietary crude protein, and decreased nitrogen and ammonia pollution [5–7]. Many studies have suggested that the energy/protein imbalanced low-protein diet enhances the risk of lipid metabolism disorders in late-phase laying hens and negatively impacts egg production rates, egg weight, and feed intake [8–10]. These effects may be due to unbalanced energy and protein levels in the diet [11]. Reducing energy levels in the LP diet to adjust the energy-to-protein ratio may improve fat deposition, but it also decreases the growth performance of chickens [12]. Feed nutrition optimization is an effective method for preventing the negative effects of LP diets [13]. However, it is difficult to develop functional feed additives that can improve lipid metabolism in the liver of late-phase laying hens. Therefore, there is an urgent need to investigate the underlying mechanisms of liver lipid metabolism in late-phase laying hens (LP diet with unbalanced energy/protein ratio) to better guide feed nutrition strategies.

Previous studies have indicated the important roles of the gut microbiota in fatty acid disease, which can affect the liver through the gut-liver axis [14]. The gut microbiota influences energy storage, lipid and choline metabolism, ethanol production, immune balance, and inflammation, all of which are relevant to the pathogenesis of lipid metabolism disorders [15]. Furthermore, changes in the gut microbiota composition have been associated with the progression of lipid metabolism disorders and the degree of fibrosis [16]. In laying hens, previous studies have shown that alterations in the cecal microbiota are closely linked to the severity of liver conditions, with changes in the abundance of specific bacterial groups associated with the progression of hepatic steatosis and lipid metabolism disorders [17, 18]. Previous research on lipid metabolism disorders in poultry has primarily focused on energy intake, and calcium deficiency [19, 20], whereas research related to protein intake is limited. Understanding the interactions between gut microbiota and liver health in laying hens fed an energy/protein imbalanced LP diet is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent and manage lipid metabolism disorders. Therefore, this study aimed to combine multiple omics techniques (transcriptomics, 16S, and metabolomics) to comprehensively analyze the impact of the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet on liver lipid metabolism in late-phase laying hens through the gut-liver axis. The results of this study are expected to be of great significance in protecting laying hens from liver lipid metabolism disorders.

Methods

Hens and dietary treatment

A total of 288 laying hens (aged 57 weeks) of strain Peking Pink (YunLing GuangDa Yukou Poultry Co. Ltd., Yunnan, China) with similar body weight were randomly divided into the following 4 groups (6 replicates of 12 hens per group): the control (CK) group, fed a normal-energy and normal-protein diet (11.15 MJ/kg, 16.59% CP), and 3 LP groups: (1) the low-energy and low-protein (LL) diet group (10.73 MJ/kg, 14.50% CP), (2) the normal-energy and low-protein (NL) diet group (11.15 MJ/kg, 14.52% CP), and (3) the high-energy and low-protein (HL) diet group (11.57 MJ/kg, 14.52% CP) (Table 1). All diets (Table 1) were formulated to meet the NY/T33-2004 requirements for hens [21], except for ME and CP in the 3 LP diets. The energy-to-protein ratios of the CK, LL, NL, and HL diets were 0.67, 0.74, 0.77, and 0.80, respectively.

Table 1.

Composition and chemical analysis of the basic diets (air-dried basis)

| Item | CK | LL | NL | HL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient, % | ||||

| Corn | 61.60 | 62.87 | 66.95 | 64.43 |

| Soybean meal | 24.70 | 17.80 | 18.96 | 19.46 |

| Wheat bran | 2.00 | 7.40 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| Soybean oil | 0.60 | - | 0.17 | 2.20 |

| Limestone powder | 9.30 | 9.48 | 9.35 | 9.32 |

| Lysine | - | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Methionine | - | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Threonine | - | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Tryptophan | - | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Arginine | - | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Leucine | - | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| Isoleucine | - | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Cysteine | - | - | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Premix1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutrition level | ||||

| ME, MJ/kg | 11.15 | 10.73 | 11.15 | 11.57 |

| crude protein, % | 16.59 | 14.50 | 14.52 | 14.52 |

| Ca, % | 3.85 | 3.85 | 3.85 | 3.85 |

| Total P, % | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| Lysine, % | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Methionine, % | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| Threonine, % | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Tryptophan, % | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Arginine, % | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.10 |

| Leucine, % | 1.42 | 1.42 | 1.42 | 1.42 |

| Isoleucine, % | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| Cysteine, % | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

1Supplying per kilogram of diet: VA 8,000–10,000 IU, VD3 2,200–5,000 IU, VE 13 IU, VK3 1.4–4.8 mg, VB1 1.8 mg, VB2 3.0 mg, VB6 2.0 mg, VB12 0.01 mg, nicotinamide 20 mg, D-calcium pantothenate 10 mg, folic acid 0.55 mg, D-biotin 0.15 mg, choline 380 mg, Fe 60 mg, Cu 8 mg, Mn 60 mg, Zn 60 mg, I 0.35 mg, Se 0.12–0.48 mg, Ca 60–180 mg

Laying hens were placed in the cage (H 0.40 m × W 0.39 m × D 0.40 m) equipped with a nipple drinker and an exterior feed. Chickens were raised in an enclosed, ventilated, conventional house under 16/8 h light/dark conditions, 20–25 °C and 55% relative humidity. According to the management procedure for breeding Peking Pink laying hens (Yukou Poultry Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), every bird was provided with 112 g diet/d and had free access to water. The experiment lasted 77 d, including a 7-d acclimation period and a 70-d experimental period. At the end of this experiment, 12 eggs from each group were obtained to measure egg quality. One chicken from each replicate was sacrificed by exsanguination. The liver and cecal digesta were harvested and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Production performance and egg quality measurement

The final body weights of laying hens were recorded before sample collection. Egg number and weight were recorded daily. Feed conversion efficiency was calculated as grams of feed intake. Yolk weight, yolk%, egg protein quality (Haugh unit), and albumen height were determined using an egg quality analyzer (Robotmation EMT-7300, Tokyo, Japan). Eggshell thickness (air cell, equator, and sharp end), egg length, and egg width were determined using a vernier caliper. Eggshell strength was determined using an egg force analyzer (Robotmation Model-III, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of lipid metabolism indices in liver

Triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TCH), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), lipase (LIP), hepatic lipase (HLP), and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) were detected using TG, TCH, and LDL-C kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (HDL-C) was detected by HDL-C kits (Suzhou Comin Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Suzhou, China), following the manufacturer’s protocols. The liver enzyme activities of fatty acid synthase (FAS) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) were detected using ELISA kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Liver RNA isolation and transcriptome sequencing

According to the results of lipid metabolism indicators, the low energy level in the LP diet led to lipid metabolism disorders. Therefore, the CK and LL groups were selected for subsequent multi-omics studies. Total RNA from the livers of laying hens in CK and LL groups was extracted using the Trizol reagent kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After quality check by agarose gel electrophoresis, mRNA was enriched with oligo(dT) beads. Paired-end 150-bp sequencing libraries were constructed using the TruSeq™ RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform by Shanghai BIOZERON Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Quality control for raw reads was executed by fastp software with the following parameters: unknown nucleotides < 10% and Q20 > 50% [22]. Bowtie2 was used for mapping reads to an rRNA database [23], and rRNA mapped reads were removed. Reference genome mapping and gene expression calculation were performed by HISAT2 [24] and RESM [25], respectively. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by DESeq2 software [26] with the threshold values: fold change > 2 and FDR-adjusted P-value < 0.05. Thereafter, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotations of DEGs were obtained from the reference genome and enrichment analysis was performed by clusterProfiler 4.0 [27]. Finally, the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of DEGs was generated using String v10 [28], and the results were visualized using Cytoscape v3.7.1 [29].

Non-targeted metabolomics for cecum contents

To extract the metabolites, 100 mg of cecal content of each hen from the CK and LL groups were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after dissection. Then, samples were homogenized with 200 μL of water and five ceramic beads. Subsequently, the homogenate was resuspended with 800 μL pre-chilled methanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v:v). The mixture was centrifuged for 15 min (14,000 × g at 4 °C) and the supernatant was dried in a vacuum centrifuge. The supernatant was re-dissolved in 100 μL acetonitrile/water (1:1, v:v) and injected onto an ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (1290 Infinity LC, Agilent Technologies) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (AB Sciex TripleTOF 6600) to separate and detect metabolites. The UHPLC-MS/MS procedure was previously described in detail [30]. The peaks of metabolites were selected using XCMS software based on the raw MS data with the following parameters: centWave m/z = 10 ppm, peakwidth = c (10, 60), prefilter = c (10, 100). For peak grouping, bw = 5, mzwid = 0.025, minfrac = 0.5. Compound identification was performed by comparing accurate m/z value (< 10 ppm) and MS/MS spectra with an in-house database established with authentic standards. Differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs) were identified based on the following parameters: P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test), VIP > 1, and fold change > 1.5.

Cecum microbiome sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from cecal contents using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of extracted DNA was checked by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoPhotometer (IMPLEN, Germany). The V3–V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified by the primers 341F and 806R with an adapter sequence and barcode at the end of the reverse primer [31]. PCR amplification and library construction were performed as previously described [32]. Libraries were sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with a 250-bp paired-end strategy at BIOZERON Biotech. Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). After sequencing, the obtained raw reads were appointed to the samples based on their unique barcode. Then, reads with average Phred scores lower than 20, that contained ambiguous bases or had more than eight homopolymer runs, that had mismatches in the primers, and/or that had sequence lengths shorter than 250 bp were removed [33]. Paired reads were assembled, chimeras were eliminated, and clean data were clustered to the amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using the DADA2 plugin unit in the QIIME2 program [34]. Singletons (where the number of a specific ASV was one) were removed and all remained ASVs were assigned to a taxon using the SILVA database (Release 138) [35]. The function of the cecal microbiome based on KEGG pathways was further predicted with PICRUSt2 software using the normalized ASV abundance table [36].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R v4.2.2 [37] and results were visualized by the “ggplot2” [38] and "pheatmap" packages [39]. First, the indices of production performance, egg quality, and liver lipid metabolism were compared by Tukey’s HSD test using the “multcomp” package. Subsequently, 4 alpha diversity indices of cecum microbiome, related to different facets, including richness (Chao1), evolution (Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, Faith_pd), diversity (Shannon), and evenness (Pielou’s evenness index, Pielou_J), were calculated by the “vegan” package. Differences in alpha diversity indices, relative abundances of dominant gut bacteria, and functional pathways of the cecal microbiome between the CK and LL groups were tested by the Student’s t-test. Meanwhile, the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances between the cecal microbiome were obtained by the “GUniFrac” package [40]. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and the adonis test based on these distances were executed with the “ape” and “vegan” packages to assess the effects of LP diets on the composition and function of cecal microbiome in laying hens. In addition, specificity and occupancy of each ASV in samples from the CK and LL groups were calculated and projected onto a SPEC-OCCU plot to explore specialists [41]. ASVs with specificity and occupancy values greater or equal to 0.7 were identified as specialists, indicating that they were specific to a specific diet.

To visualize the co-occurrence network of the cecal microbiome, Spearman’s rank correlations among all ASVs of samples from the CK and LL groups were calculated with the “WGCNA” package. A correlation between two genes was considered statistically robust if |correlation coefficient| > 0.8 and P < 0.01. Network graphs were visualized using the Gephi interactive platform and the topological parameters of networks were calculated with the “igraph” package [42]. Robustness and vulnerability of co-occurrence networks were calculated to evaluate the stability of the cecal microbiome according to a previous study [43]. The topological roles of individual ASVs in networks were evaluated by the threshold values of Pi (measuring how well a node was connected to nodes in different modules) and Zi (measuring how well a node was connected to other nodes in its own module) to identify potential key taxa [44]. Finally, correlations among the lipid metabolism indices in liver, DEGs in liver, DAMs in cecum, and key functional terms and bacteria in the cecal microbiome were analyzed by the Pearson correlation method with the “psych” package to explore the potential interactions in the gut-liver axis.

Results

Laying performance

As shown in Table 2, dietary treatment did not have a significant effect on laying rate and feed efficiency. The final body weight and average daily gain were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the HL group than in the CK and LL groups. The egg weight was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the HL group than in the LL group.

Table 2.

Effects of different energy levels in LP diet on the laying performance of aged laying hens

| Item | CK1 | Dietary energy level in LP diet2 | SEM3 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | NL | HL | ||||

| Initial body weight, g | 1,904.04 | 1,897.83 | 1,905.50 | 1,905.33 | 1.945 | 0.324 |

| Final body weight, g | 2,039.17bc | 1,987.00c | 2,056.83ab | 2,107.83a | 11.263 | < 0.001 |

| Average daily gain, g/d | 1.67bc | 1.27c | 2.16ab | 2.89a | 0.154 | < 0.001 |

| Egg weight, g | 62.35ab | 61.46b | 62.52ab | 63.25a | 0.222 | 0.028 |

| Laying rate, % | 82.05 | 86.46 | 82.68 | 80.94 | 0.010 | 0.256 |

| Feed efficiency, g/g | 2.26 | 2.23 | 2.27 | 2.29 | 0.025 | 0.820 |

1The positive control group (CK): Normal-energy and normal-protein diet

2The experimental group (IELP) included the low-energy and low-protein diet group (LL), the normal-energy and low-protein diet group (NL), and the high-energy and low-protein diet group (HL)

3SEM = standard error of the mean

Egg quality

The effects of different energy levels in the LP diets on egg quality are shown in Table 3. No significant differences in the egg shape index, eggshell thickness, eggshell strength, albumen height, yolk weight, and yolk ratio were observed among different treatment groups. In contrast, the Haugh units were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the HL group than in the CK group.

Table 3.

Effects of different energy levels in LP diet on the egg quality of aged laying hens

| Item | CK1 | Dietary energy level in LP diet2 | SEM3 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | NL | HL | ||||

| Average egg weight, g | 62.77 | 59.79 | 62.35 | 61.97 | 0.654 | 0.398 |

| Egg shape index, % | 1.29 | 1.27 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.004 | 0.090 |

| Eggshell thickness, mm | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.0180 | 0.116 |

| Eggshell strength, N | 3.92 | 4.13 | 3.67 | 3.97 | 0.108 | 0.545 |

| Albumen height, mm | 6.84 | 6.28 | 6.62 | 5.97 | 0.210 | 0.501 |

| Haugh units | 81.73a | 81.39ab | 79.02ab | 71.92b | 1.402 | 0.034 |

| Yolk weight, g | 17.45 | 17.45 | 16.74 | 17.03 | 0.155 | 0.297 |

| Yolk ratio | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.005 | 0.262 |

1The positive control group (CK): Normal-energy and normal-protein diet

2The experimental group (IELP) included the low-energy and low-protein diet group (LL), the normal-energy and low-protein diet group (NL), and the high-energy and low-protein diet group (HL)

3SEM = standard error of the mean

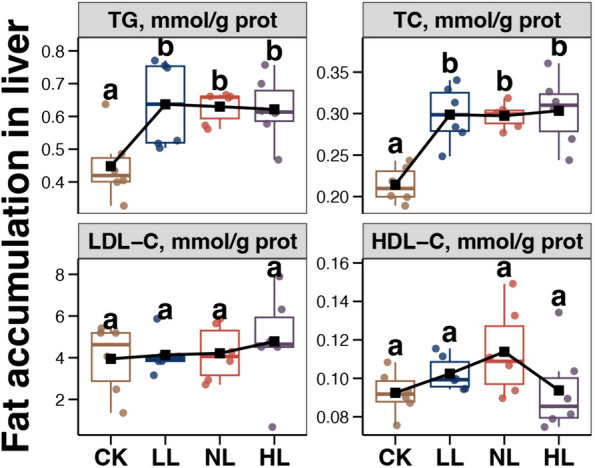

Liver fat accumulation

The effects of different energy levels on TG, TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C in the laying hens fed the LP diet are shown in Fig. 1. Compared with the CK group, TG and TC levels were higher in the hens fed LP diets (LL, NL, and HL groups). In contrast, there were no significant differences in LDL-C and HDL-C levels among the 4 groups.

Fig. 1.

Differences of fat level indice in the liver of aged laying hens among different groups. Different lowercase letters in each box of the same sub-figure represent significant differences among aged laying hens from different groups (Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05)

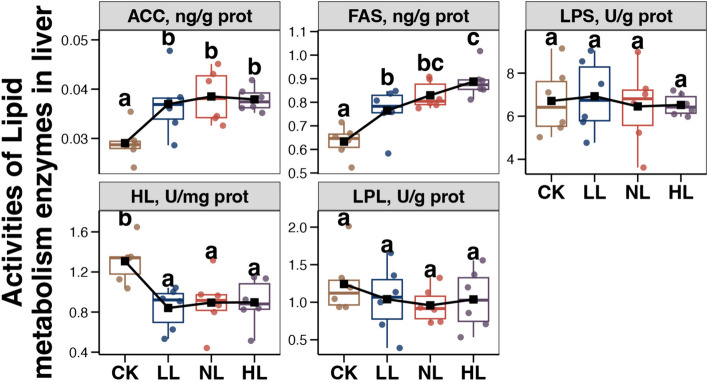

Lipid metabolism-related enzymes in the liver

The effects of different energy levels in LP diets on the activities of liver lipid metabolism-related enzymes are shown in Fig. 2. Compared with the CK group, ACC and FAS levels were significantly increased (P < 0.05), but that of HLP was decreased (P < 0.05) in the livers of laying hens fed LP diets (LL, NL, and HL groups). There were no significant differences in LPS activity among the 4 groups.

Fig. 2.

Variations in the activities of lipid metabolic enzymes in the liver of aged laying hens among different groups. Different lowercase letters in each box of the same sub-figure represent significant differences among aged laying hens from different groups (Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05)

Gene expression in liver

Based on the above results, the low energy level in the LP diet led to liver lipid metabolism disorders in laying hens. Therefore, the CK and LL groups were selected to study the relationship between gut microbes and liver lipid metabolism using a multi-omics strategy.

For both the CK and LL groups, six libraries were constructed for RNA-Seq analysis. From the library, 42,423,838 to 51,104,686 sequenced reads were generated with a low-quality ratio below 1% and approximately 1% rRNA reads (Table S1). Approximately 95% of the clean reads were mapped to the reference genome, with an exon rate > 85% and 17,007 genes (Table S2). Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed according to gene expression levels, and the results showed distinct gene expression profiles between the CK and LL samples (Fig. 3a). Subsequently, 181 DEGs were identified from the transcriptomic data, with 115 upregulated and 66 downregulated genes in the livers of the LL group compared to those in the CK group (Fig. 3b). The DEGs were mainly related to lipid, carbohydrate, and amino acid metabolism (Fig. 3c). In addition, some genes related to the endocrine system, transport, and signal transduction were differentially expressed between the CK and LL groups (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, the KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the LL diet influenced the liver functions of the laying hens related to lipid metabolism (fatty acid metabolism and degradation), energy metabolism (pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and galactose metabolism), amino acid metabolism (valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation, and beta-alanine metabolism), circadian rhythm, and PPAR signaling pathway (Fig. 3d). Finally, the PPI network of DEGs revealed some potential key genes that were influenced by the LP diet, including genes related to fatty acid beta-oxidation (ACOX1, HADHA, EHHADH, and ACAA1), fatty acid biosynthesis (SCD, FASN, and ACACA), lipid transport (TTR, ALDH1A3, and ADH1C), and energy metabolism (CYP7A1, PCK1, PPARGC1A, PGK2, PDHA2, and LDHB) (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Liver transcriptome of aged laying hens fed an LP diet. a PCA exhibiting the variations in the gene expression profiles. b Volcano plot showing the results of DEG identification. c KEGG annotation of DEGs. d KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs. e The PPI network of DEGs

Metabolites in cecum

A total of 5,149 metabolites were detected in CK and LL samples using UPLC-MS/MS metabolic analysis. Orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) revealed that cecal metabolites in hens fed the same diet were clustered together and away from others (Fig. 4a), suggesting obvious effects of the LL diet on the cecal metabolism of the laying hens. In total, 350 DAMs were identified among the cecal metabolites between the LL and CK groups, with 108 upregulated and 242 downregulated DAMs in the LL group (Fig. 4b). Cecal metabolites that were most significantly impacted by the LL diet included riboflavin (vitamin B2), pantethine (a derivative of vitamin B5), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), 4-pyridoxic acid, cytidine, biotin, 6-hydroxyhexanoate, pyruvate, and asiatic acid (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the vitamin B6 metabolism and folate biosynthesis pathways were found to be enriched in the cecum of laying hens fed an LL diet (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Cecal metabolites of aged laying hens in the CK and LL groups. a OPLS-DA revealing the variations in cecal metabolites. b Volcano plot showing the results of DAM identification. c VIP plot exhibiting the DAMs with the strongest variation between the CK and LL groups. d KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DAMs

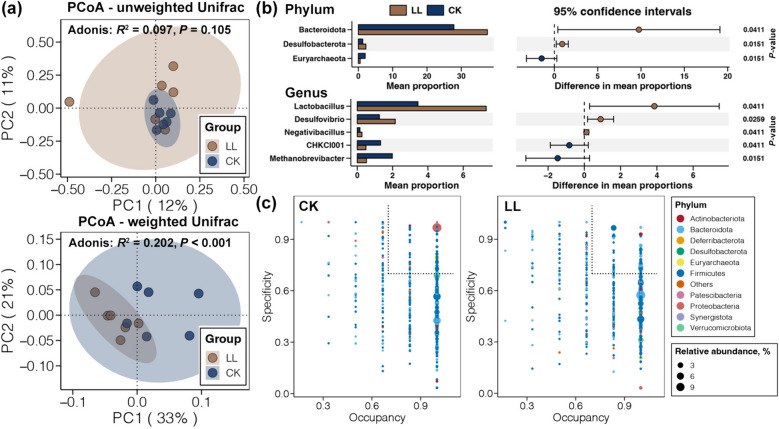

Cecal microbiome

On average, 129,625 reads of the 16S rRNA V3–V4 region were obtained for the cecal microbiome of CK and LL samples (Table S2). After quality control, 93,573 to 107,196 high-quality reads were retained per sample, with an effective ratio of 78.39% (Table S3). These reads were clustered into 6,804 ASVs with an average of 1,164 ASVs per sample, which were annotated to 25 phyla, 43 classes, 100 orders, 132 families, 168 genera, and 107 species (Table S3). All ASVs were successfully annotated to a bacterial phylum, but only 36.78% ASVs were assigned to a taxon at the genus level (Fig. S1a). Generally, the numbers of obtained bacteria at all taxonomic levels were higher in LL samples compared to CK samples (Table S3). However, changes in the alpha diversity of cecal microbiome induced by the LL diet were not significant (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, Fig. S1b). PCoA and the adonis test based on the unweighted UniFrac distance also showed insignificant variations in the compositions of the cecum microbiome between the CK and LL groups (P > 0.05, Fig. 5a), but significant changes in the cecal microbiome compositions were revealed by the PCoA and adonis test based on the weighted UniFrac distance (P < 0.05, Fig. 5a). The unweighted UniFrac distance only considers the composition of the species without taking into account their relative abundance; in contrast, the weighted UniFrac distance considers not only the composition of species but also their relative abundance [45]. Our findings indicate that the changes in the cecal microbiome induced by the LL diet are mainly variations in the relative abundance of major bacteria.

Fig. 5.

Variations in the composition of the cecal microbiome induced by the LP diet. a PCoA and the adonis test based on the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances revealing the differences in cecal microbiome composition between the CK and LL groups. b Bacterial phyla and genera with significant variation in relative abundance in the cecum between the CK and LL groups (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05). c SPEC-OCCU plots showing ASVs in the cecal microbiome of aged laying hens fed a normal or LP diet

Firmicutes and Bacteroidota dominated in the cecal microbiomes of laying hens, followed by Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobiota (Fig. S2). Bacteroidota and Desulfobacterota were more abundant in the cecum of laying hens fed the LL diet, while the relative abundance of Euryarchaeota was decreased (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, Fig. 5b). At the genus level, Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group was the most abundant, followed by Bacteroides, Ruminococcus torques group, Escherichia-Shigella, and Lactobacillus (Fig. S3). The relative abundances of Lactobacillus, Desulfovibrio, and Negativibacillus were increased by the LL diet, while CHKCI001 and Methanobrevibacter were eliminated (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, Fig. 5b). Moreover, SPEC-OCCU plots were applied to explore potential specialists in the cecum microbiome of laying hens fed the LP diet (Fig. 5c). A total of 57 and 55 ASVs were recognized as potential specialists for the normal and LP diets, respectively. Most of them were members of Firmicutes (46 and 35 for CK and LL groups, respectively). More importantly, the number of specialists belonging to the Bacteroidota was only 4 in the CK group, but it was 17 in the LL group.

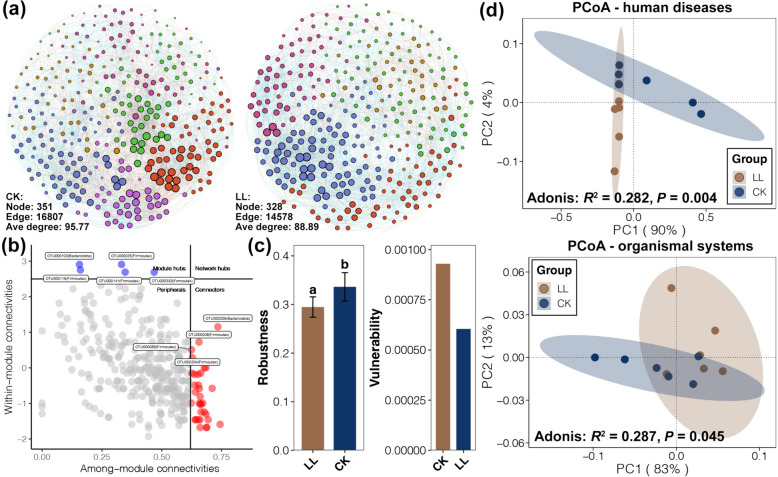

Co-occurrence networks of the cecal microbiome of laying hens fed a normal or LL diet were further constructed (Fig. 6a). The co-occurrence pattern in cecal microbiome was slightly simple for laying hens fed by the LL diet according to the topological parameters of networks (lower number of nodes, number of edges, and degrees). Meanwhile, five ASVs were recognized as module hubs of the co-occurrence network, including 4 Firmicutes and one Bacteroidota (Fig. 6b). Lower robustness and higher vulnerability were found in network of LL samples compared to CK individuals (Fig. 6c), suggesting weak stability of the cecal microbiome in the laying hens fed the LL diet. In addition, the predicted functions of cecal microbiota were compared between the LL and CK groups. Although changes in the whole cecal microbiome functions were insignificant (adonis test, P > 0.05, Fig. S4), obvious differences in the functions related to human disease and organismal systems were found between the cecal microbiome of the LL and CK groups (adonis test, P < 0.05, Fig. 6d and Fig. S5). Moreover, two metabolism functions, lipid metabolism and secondary bile acid biosynthesis, were found to be enriched in the cecal microbiome of laying hens fed the LL diet (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, Fig. S6). In contrast, functions including C5-branched dibasic acid metabolism, nitrotoluene degradation, and riboflavin metabolism in the cecal microbiome of laying hens were weakened by the LL diet (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, Fig. S6).

Fig. 6.

Co-occurrence network and predicted function of the cecal microbiome. a Co-occurrence networks of the cecal microbiome from the CK and LL samples. Nodes belonging to different modules are labeled in different colors. b Zi-Pi plot showing the distribution of bacterial ASVs based on their topological roles. c Robustness and vulnerability of networks of the LL and CK groups. Different lowercase letters above the bars of the robustness plot represent a significant difference between the CK and LL groups (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05). d PCoA and adonis test based on the Bray–Curtis distance revealing the differences in cecal microbiome functions related to human disease and organismal systems between the CK and LL groups

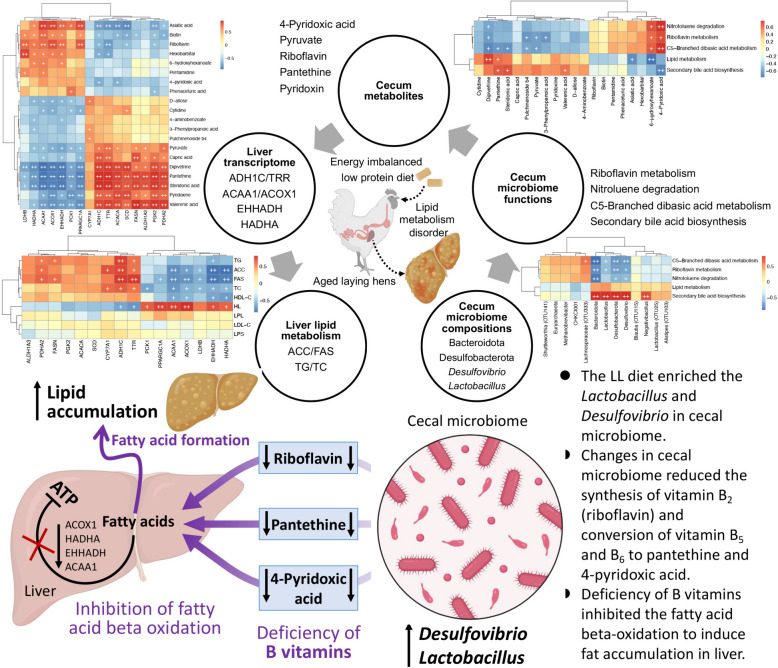

Roles of the gut-liver axis

To explore the underlying mechanisms of liver lipid metabolism disorder in the laying hens fed LL diets, correlation analyses were performed between any two indices of liver lipid metabolism, liver DEGs, cecal DAMs, different cecal microbiome functions, and different cecal bacteria (Fig. 7). Based on the significant relationships, potential keystones related to lipid metabolism disorder were observed, including 4 liver lipid metabolism indices, 6 liver genes, 5 cecal metabolites, 4 cecal microbial functions, and 4 cecal bacteria. According to these functions and significant correlations, we deduced the underlying mechanism for lipid metabolism disorder in the laying hens fed the LL diet. LL dietary treatment enriched Desulfovibrio and Lactobacillus in the cecum of the laying hens, which inhibited the biosynthesis of vitamin B2 (riboflavin), pantethine (a derivative of vitamin B5), and 4-pyridoxic acid (the end product of vitamin B6 catabolism). The deficiency of B vitamins restrained the expression of genes related to the beta-oxidation of fatty acids (ACOX1, HADHA, EHHADH, and ACAA1) in liver, resulting in the accumulation of lipid in the liver.

Fig. 7.

Correlation analyses among liver lipid metabolism indices, liver DEGs, cecum DAMs, different cecal microbiome functions, and different cecal bacteria, and the conceptual frameworks of deduced mechanisms of lipid metabolism disorder in aged laying hens fed the LL diet

Discussion

Liver lipid metabolism disorders often occur in late-phase laying hens after experiencing peak production [46]. We explored mechanisms underlying the harmful effects of the energy/protein imbalanced LP diets on laying hens to provide recommendations for improvement. Previous studies have indicated that the production performance and egg quality of laying hens fed the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet were decreased [13, 47]. Our results are consistent with these studies, showing an adverse effect of the HL diet on laying rate and egg quality. As the late-phase laying hens, the increased weight and the amount of abdominal fat may reduce production performance [48]. In the present study, the final body and egg weight was markedly increased in the HL group which was harmful to the late-phase laying hens according to the management procedure for breeding Peking Pink laying hens (Yukou Poultry Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). More importantly, our findings demonstrated that the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet disrupted lipid metabolism and resulted in fat accumulation in the livers of the late-phase laying hens, which is consistent with previous findings [49]. The principal cause of lipid metabolism disorders in laying hens is thought to be excessive calorie intake, which leads to an incorrect energy/protein balance in the diet [50, 51]. In this study, the energy-to-protein ratios in the LP groups (LL, NL, and HL groups) were much higher than that in the CK group.

The expression levels of some genes involved in fatty acid synthesis were upregulated in the livers of the late-phase laying hens fed LP diets (Fig. 3). ACACA encodes a biotin-containing enzyme that catalyzes the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which is the rate-limiting step in fatty acid synthesis [52]. FASN encodes a multifunctional protein that catalyzes the synthesis of palmitate from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA into long-chain saturated fatty acids in the presence of NADPH [53]. The effect of these genes on the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet was further confirmed by the results of enzyme activities (Fig. 2). In contrast, genes involved in the beta-oxidation of fatty acids were downregulated in the livers of the late-phase laying hens fed an energy/protein imbalanced LP diet (Fig. 3). ACOX1 encodes the first enzyme in the fatty acid beta-oxidation pathway that catalyzes the desaturation of acyl-CoAs to 2-trans-enoyl-CoAs [54]. HADHA encodes the alpha subunit of the mitochondrial trifunctional protein, which catalyzes the last 3 steps of the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids [55]. EHHADH and ACAA1 encode 2 of the 4 enzymes involved in the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway [56, 57]. These findings suggest that fat accumulation in the liver of late-phase laying hens fed an energy/protein imbalanced LP diet was attributable to both promotion of fatty acid biosynthesis and the suppression of fatty acid utilization.

The composition and function of the gut microbiota are closely related to host health, and diet is an important factor in regulating the homeostasis of gut microbiota [58]. Several studies have revealed the potential negative effects of an energy/protein imbalanced LP diet on the gut microbiota of animals [59]. Our results revealed that two bacterial genera, Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio, might be key cecal microbes that respond to the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet, both of which were enriched in hens fed LL diets (Fig. 5b). A study on broiler chickens showed that reduced intake of crude protein increased the abundance of Lactobacillaceae in the cecum over time [60]. In addition, Zhong et al. [61] indicated that a high-protein diet could reduce gut Lactobacillus, which was consistent with the results of this study. Furthermore, Raman et al. [62] and Nobili et al. [63] reported that gut Lactobacillus were markedly increased in humans with lipid metabolic disorders of the liver. In contrast, another cecal bacterium enriched by the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet, Desulfovibrio, has been associated with several diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, bacteremia, and Parkinson’s disease [64]. Moreover, research has shown that Desulfovibrio dysregulation is associated with fatty acid levels and modulation of Desulfovibrio may be a potential strategy for the treatment of lipid metabolism disorders [65]. Our results highlight the possible roles of Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio in the cecal microbiome of laying hens during the development of lipid metabolism disorders.

In our study, we observed that some cecal metabolites which lower liver fatty acid decomposition were significantly decreased in late-phase laying hens fed the LL diets, such as riboflavin (vitamin B2) and pantethine (a derivative of vitamin B5) (Fig. 4c), whose deficiency has been demonstrated to impair lipid metabolism by depressing fatty acid beta-oxidation [66–68]. Subsequently, association analyses based on multi-omics data were performed to explore the underlying relationships between variations in the cecal microbiome and lipid metabolism disorders in liver with a deficiency of riboflavin and pantethine in laying hens fed an energy/protein imbalanced LP diet. These findings revealed potential avenues for further research on dietary interventions, microbiota modulation, and the development of targeted treatments to support the liver health of poultry.

Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, is a key vitamin that plays an important role in breaking down nutrients in food to produce energy [69]. Animals cannot synthesize vitamin B2, which is primarily sourced from food or is synthesized by the gut microbiota [70]. The role of vitamin B2 in functional rescue of mitochondrial beta-oxidation flavoenzymes for fatty acid degradation has also been proven [71]. Our results showed that riboflavin metabolism was inhibited in the cecal microbiome of the late-phase laying hens fed an LL diet. Significant correlations were observed among the enriched cecal bacteria (Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio), decreased riboflavin metabolism in the cecal microbiome, downregulated cecal riboflavin, and downregulated liver genes related to beta-oxidation of fatty acids (ACOX1, HADHA, EHHADH, and ACAA1) (Fig. 7). Moreover, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), a B-complex vitamin, was significantly enriched and 4-pyridoxic acid (the primary catabolic product of vitamin B6) was scarce in the ceca of the late-phase laying hens fed an LL diet. Decreased levels of 4-pyridoxic acid are associated with impaired fatty acid beta-oxidation in poultry [72, 73]. In addition to its metabolic role, vitamin B2 enables the conversion of vitamin B6 into its active form [74]. Previous studies have also found that riboflavin is an important determinant of vitamin B6 status in healthy adults [75, 76]. Significant correlations between the levels of vitamins B2, B6, and 4-pyridoxic acid were observed (Fig. 7). These results indicate that the metabolic rate of vitamin B6 is inhibited in laying hens fed the LL diet due to deficiencies in vitamin B2, which leads to the accumulation of vitamin B6, but insufficient 4-pyridoxic acid in the cecum. Taken together, we deduced that variations in the cecal microbiome of the late-phase laying hens induced by the energy/protein imbalanced LL diet led to vitamin B2 deficiency, which further inhibited the beta-oxidation of fatty acids in the liver and resulted in lipid metabolism disorders.

Pantethine, another downregulated cecal metabolite, is the active form of pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), which is an essential component of coenzyme A (CoA) [67, 77, 78]. CoA is involved in the transport of fatty acids to the mitochondria, where fatty acid beta-oxidation occurs [79]. CoA is also the only source of the phosphopantetheine prosthetic group for enzymes that shuttle intermediates between the active sites of enzymes involved in fatty acid metabolism [80]. In addition, CoA is a source of the 4'-phosphopantetheinyl prosthetic group present in the acyl carrier protein, which is required for fatty acid synthesis in biological systems [81]. Many studies have demonstrated that pantethine has anticatabolic properties in fatty acid synthesis and stimulates fatty acid oxidation [82, 83]. Pantetheine has been used in humans as a lipid-lowering drug and dietary pantethine has also been shown to improve liver lipogenesis in laying hens [84, 85]. In our study, the decreased level of pantethine in the cecum of the late-phase laying hens fed an LL diet was also significantly correlated with the downregulated expression of genes related to fatty acid beta-oxidation and enriched key cecal bacteria (Fig. 7). These associations indicate that the lipid metabolism disorder caused by the LP diet in late-phase laying hens may also be related to the pantethine deficiency induced by variations in the cecal microbiome.

Conclusions

The energy/protein imbalanced LP diet significantly altered fat accumulation in the livers of late-phase laying hens. The inhibition of beta-oxidation and promotion of fatty acid biosynthesis in the liver of the late-phase laying hens directly contributed to the fat accumulation induced by the energy/protein imbalanced LP diet. The energy/protein imbalanced LP diet influenced the cecal microbiome, resulting in enriched Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio genera. Moreover, our results revealed the deficiencies of vitamins B2 and pantethine in late-phase laying hens fed an energy/protein imbalanced LP diet owing to changes in the cecal microbiome. This may explain the weak fatty acid beta-oxidation ability and strengthened fatty acid synthesis in the liver. These results provide insights into mechanisms underlying liver lipid metabolism disorders and their association with the gut-liver axis in the late-phase laying hens fed LP diets. Based on these results, we propose that supplementing vitamin B2 and pantethine may effectively prevent lipid metabolism disorders in the late-phase laying hens fed an LP diet.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Statistics of transcriptome sequencing for liver of aged laying hens. Table S2. Statistics of cecal microbiome sequencing of aged laying hens. Table S3. Numbers of taxa detected in cecal microbiome of aged laying hens. Fig. S1. (a) Ratio of successful annotation of ASVs in cecal microbiome of aged laying hens. (b) Variations in the alpha diversity of cecal microbiome of aged laying hens among different treatments. Fig. S2. Relative abundance of major bacterial phyla in cecum of aged laying hens. Fig. S3. Relative abundance of top 10 bacterial genera in cecal microbiome of aged laying hens fed by the LP and normal diets. Fig. S4. PCoA and adonis test based on the Bary-Curtis distance revealing the changes in cecal microbiome function between the CK and LL groups. Fig. S5. PCoA and adonis test based on the Bary-Curtis distance revealing the changes in cecal microbiome function related to metabolism, cellular processes, environmental information processing, and genetic information processing between the CK and LL groups. Fig. S6. Bacterial functions with significant variations in relative abundance in the cecum between the CK and LL groups (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Dong Chen, Yang He, and Yangshuo Pan for their assistance with the experimental samples collection.

Abbreviations

- ACAA1

Acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1

- ACACA

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha

- ACC

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ACOX1

Acyl-CoA oxidase 1

- ADH1C

Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C

- ALDH1A3

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A3

- ASVs

Amplicon sequence variants

- CK

Positive control

- CoA

Coenzyme A

- CYP7A1

Cytochrome P450 family 7 subfamily A member

- DAMs

Differentially abundant metabolites

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- EHHADH

Enoyl-CoA hydratase and 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase

- Faith_pd

Faith’s phylogenetic diversity

- FAS

Fatty acid synthase

- FASN

Fatty acid synthase

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- HADHA

Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase trifunctional multienzyme complex subunit alpha

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HL

High-energy and low-protein diet

- HLP

Hepatic lipase

- LDHB

Lactate dehydrogenase B

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LIP

Lipase

- LL

Low-energy and low-protein diet

- LP

Low-protein

- LPL

Lipoprotein lipase

- NL

Normal-energy and low protein diet

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis

- PCA

Principal components analysis

- PCoA

Principal coordinate analysis

- PCK1

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1

- PDHA2

Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit alpha 2

- PGK2

Phosphoglycerate kinase 2

- Pielou_J

Peilou’s evenness index

- PPI

Protein–protein interaction

- PPARGC1A

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha

- SCD

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- TCH

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- TTR

Transthyretin

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: YH and HP. Collection and assembly of data: HH, AL, QM, KW and XB. Data analysis and interpretation: LC, ZZ, QZ and XB. Manuscript writing: HH, ZZ and XB. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Funding

This work was supported by China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS-40-S25), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFD1601905), the Industrial Innovation Talent Project of the “Xing Dian Talent Support Program” of Yunnan Province in 2022 (XDYC-CYCX-2022–0029) and the Young Talent Project of the “Xing Dian Talent Support Program” of Yunnan Province in 2023.

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the China National GeneBank Sequence Archive (CNSA) of the China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) with the accession number CNP0005028 and CNP0005031.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yunnan Agricultural University (Approval Number: 202202001).

Consent for publication

All of the authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed with this submission to the Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Hong Hu and Ying Huang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xi Bai, Email: baixi1987326@163.com.

Hongbin Pan, Email: ynsdyz@163.com.

References

- 1.Underwood G, Andrews D, Phung T. Advances in genetic selection and breeder practice improve commercial layer hen welfare. Anim Prod Sci. 2021;61(10):856–866. doi: 10.1071/AN20383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzarah MI, Alaqil AA, Abbas AO, Nassar FS, Mehaisen GM, Gouda GF, et al. Inclusion of Citrullus colocynthis seed extract into diets induced a hypoli-pidemic effect and improved layer performance. Agriculture. 2021;11(9):808. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11090808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Liu M, Ding Y, Wang T, Ma Y, Huang J, et al. Effects of perilla seed meal on productive performance, egg quality, antioxidant capacity and hepatic lipid metabolism of Wenchang breeder hens. Animals. 2023;13(22):3587. doi: 10.3390/ani13223587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shini A, Shini S, Bryden WL. Fatty liver haemorrhagic syndrome occurrence in laying hens: impact of production system. Avian pathol. 2019;48(1):25–34. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2018.1538550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Such N, Pál L, Strifler P, Horváth B, Koltay IA, Rawash MA, et al. Effect of feeding low protein diets on the production traits and the nitrogen composition of excreta of broiler chickens. Agriculture. 2021;11(8):781. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11080781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thirumalaisamy G, Muralidharan J, Senthilkumar S, HemaSayee R, Priyadharsini M. Cost-effective feeding of poultry. Int J Sci Environ Technol. 2016;5(6):3997–4005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos S, Girish C. Application of low protein diet concept for sustainable poultry production. N Zeal Poult Industry Confer. 2018;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozenboim I, Mahato J, Cohen NA, Tirosh O. Low protein and high-energy diet: a possible natural cause of lipid metabolism disorder hemorrhagic syndrome in caged White Leghorn laying hens. Poult Sci. 2016;95(3):612–621. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambrosen T, Petersen VE. The influence of protein level in the diet on cannibalism and quality of plumage of layers. Poult Sci. 1997;76(4):559–563. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torki M, Mohebbifar A, Ghasemi HA, Zardast A. Response of laying hens to feeding low-protein amino acid-supplemented diets under high ambient temperature: performance, egg quality, leukocyte profile, blood lipids, and excreta pH. Internat J biometeorol. 2015;59:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s00484-014-0870-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shim MY, Song E, Billard L, Aggrey SE, Pesti GM, Sodsee P. Effects of balanced dietary protein levels on egg production and egg quality parameters of individual commercial layers. Poult sci. 2013;92(10):2687–2696. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamran Z, Sarwar M, Nisa M, Nadeem MA, Mahmood S, Babar ME, et al. Effect of low-protein diets having constant energy-to-protein ratio on performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens from one to thirty-five days of age. Poult Sci. 2008;87(3):468–474. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun M, Ma N, Liu H, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Zhao J, et al. The optimal dietary arginine level of laying hens fed with low-protein diets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2022;13:63. 10.1186/s40104-022-00719-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Yang C, Xu J, Xu X, Xu W, Tong B, Wang S, et al. Characteristics of gut microbiota in patients with metabolic associated lipid metabolism disorder disease. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9988. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-37163-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau E, Carvalho D, Freitas P. Gut microbiota: association with NAFLD and metabolic disturbances. BioMed Res Internat. 2015;2015:979515. doi: 10.1155/2015/979515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maestri M, Santopaolo F, Pompili M, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani FR. Gut microbiota modulation in patients with non-alcoholic lipid metabolism disorder disease: Effects of current treatments and future strategies. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1110536. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1110536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Wang Y, Wang C, Sun X, Gao S, Liu R, et al. Alterations in hepatic transcriptome and cecum microbiota underlying potential ways to prevent early lipid metabolism disorder in laying hens. Poul Sci. 2023;102(5):102593. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang X, Li D, Zhang M, Feng Y, Jin X, Liu D, et al. Ginkgo biloba extract alleviates lipid metabolism disorder hemorrhagic syndrome in laying hens via reshaping gut microbiota. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2023;14(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s40104-023-00900-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han GP, Kim DY, Kim KH, Kim JH, Kil DY. Effect of dietary concentrations of metabolizable energy and neutral detergent fiber on productive performance, egg quality, lipid metabolism disorder incidence, and hepatic fatty acid metabolism in aged laying hens. Poult Sci. 2023;102(4):102497. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang S, Cheng HW, Cui LY, Zhou ZL, Hou JF. Changes of blood parameters associated with bone remodeling following experimentally induced lipid metabolism disorder in laying hens. Poult Sci. 2013;92(6):1443–1453. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China. NY/T—2004 Feeding standard of chicken. Beijing: China Agricultural Press; 2004.

- 22.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z, et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2(3):100141. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v10: protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43(1):447–452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang J, Zhao Z, Pan Y, Dong Y, Gao S, Li S, et al. Gender specific differences of immune competence in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus before and after spawning. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2019;90:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg J, Brandt KK, Al-Soud WA, Holm PE, Hansen LH, Sørensen SJ, et al. Selection for Cu-tolerant bacterial communities with altered composition, but unaltered richness, via long-term Cu exposure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7438–7446. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01071-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Z, Jiang J, Zheng J, Pan Y, Dong Y, Chen Z, et al. Exploiting the gut microbiota to predict the origins and quality traits of cultured sea cucumbers. Environ Microbiol. 2022;24(9):3882–3897. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:57–59. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Rideout JR, Dillon M, Bolyen E, Knight R, et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with qiime 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018;6:90. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, et al. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:643–648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Douglas GM, Maffei VJ, Zaneveld JR, Yurgel SN, Brown JR, Taylor CM, et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:685–688. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0548-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawley MJ. Statistics: an introduction using R. New Jersey, USA: John Wiley Sons. Hoboken; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkinson L. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis by WICKHAM, H. Biometrics. 2011;67(2):678–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01616.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolde R, Kolde MR. Package ‘pheatmap’. R package. 2015;1(7):790. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong RG, Wu JR, Gloor GB. Expanding the UniFrac toolbox. PloS one. 2016;11(9):e0161196. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Gweon HS, Bowes MJ, Moorhouse HL, Oliver AE, Bailey MJ, Acreman MC, et al. Contrasting community assembly processes structure lotic bacteria metacommunities along the river continuum. Environ Microbiol. 2021;23(1):484–498. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media: San Jose, CA, USA. 2009. 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937.

- 43.Yuan MM, Guo X, Wu L, Zhang YA, Xiao N, Ning D, et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat Clim Chang. 2021;11(4):343–348. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-00989-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Z, Li H, Sun Y, Zhan A, Lan W, Woo SP, et al. Bacteria versus fungi for predicting anthropogenic pollution in subtropical coastal sediments: assembly process and environmental response. Ecol Indicat. 2022;134:108484. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lozupone C, Lladser ME, Knights D, Stombaugh J, Knight R. UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J. 2011;5:169–172. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun L, Xin Q, Jiao H, Wang X, Zhao J, Li H, et al. Effect of exogenous bile salts supplementation on the performance and hepatic lipid metabolism of aged laying hens. J Anim Sci. 2023;101:334. doi: 10.1093/jas/skad334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azzam MMM, Dong XY, Zou XT. Effect of dietary threonine on laying performance and intestinal immunity of laying hens fed low-crude-protein diets during the peak production period. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2017;101(5):e55–66. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Artdita CA, Zhuang YR, Liu TY, Cheng CY, Hsiao FSH, Lin YY. The effect of feeding restriction on the microbiota and metabolome response in late-phase laying hens. Animals. 2021;11(11):3043. doi: 10.3390/ani11113043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.You M, Zhang S, Shen Y, Zhao X, Chen L, Liu J, et al. Quantitative lipidomics reveals lipid perturbation in the liver of lipid metabolism disorder hemorrhagic syndrome in laying hens. Poult Sci. 2023;102(2):102352. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moon YS. Lipid metabolism and fatty liver in poultry. KJPS. 2018;45(2):109–118. doi: 10.5536/kjps.2018.45.2.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shini A, Shini S, Bryden WL. Lipid metabolism disorder haemorrhagic syndrome occurrence in laying hens: impact of production system. Avian Pathol. 2019;48(1):25–34. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2018.1538550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhattacharjee K, Nath M, Choudhury Y. Fatty acid synthesis and cancer: Aberrant expression of the ACACA and ACACB genes increases the risk for cancer. Meta Gene. 2020;26:100798. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2020.100798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorn C, Riener MO, Kirovski G, Saugspier M, Steib K, Weiss TS, et al. Expression of fatty acid synthase in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Clin Exp Patho. 2010;3(5):505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moreno-Fernandez ME, Giles DA, Stankiewicz TE, Sheridan R, Karns R, Cappelletti M, et al. Peroxisomal β-oxidation regulates whole body metabolism, inflammatory vigor, and pathogenesis of nonalcoholic lipid metabolism disorder disease. JCI Insight. 2018;3(6):e93626. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miklas JW, Clark E, Levy S, Detraux D, Leonard A, Beussman K, et al. TFPa/HADHA is required for fatty acid beta-oxidation and cardiolipin re-modeling in human cardiomyocytes. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4671. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12482-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Houten SM, Denis S, Argmann CA, Jia Y, Ferdinandusse S, Reddy JK, et al. Peroxisomal L-bifunctional enzyme (EHHADH) is essential for the production of medium-chain dicarboxylic acids. J lipid res. 2012;53(7):1296–1303. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M024463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Long B, Muhamad R, Yan G, Yu J, Fan Q, Wang Z, et al. Quantitative proteomics analysis reveals glutamine deprivation activates fatty acid β-oxidation pathway in HepG2 cells. Amino Acids. 2016;48:1297–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat. 2019;16(1):35–56. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsu CK, Su SC, Chang LC, Shao SC, Yang KJ, Chen CY, et al. Effects of low protein diet on modulating gut microbiota in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(16):3839. doi: 10.7150/ijms.66451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Cesare A, do Valle IF, Sala C, Sirri F, Astolfi A, Castellani G, et al. Effect of a low protein diet on chicken ceca microbiome and productive performances. Poult Sci. 2019;98(9):3963–3976. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhong W, Wang H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Lai H, Cheng Y, et al. High-protein diet prevents fat mass increase after dieting by counteracting Lactobacillus-enhanced lipid absorption. Nat Metab. 2022;4:1713–1731. doi: 10.1038/s42255-022-00687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raman M, Ahmed I, Gillevet PM, Probert CS, Ratcliffe NM, Smit S, et al. Fecal microbiome and volatile organic compound metabolome in obese humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol H. 2013;11:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nobili V, Putignani L, Mosca A, Del Chierico F, Vernocchi P, Alisi A, et al. Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli in the gut microbiome of children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: which strains act as health players? Arch Med Sci. 2018;14(1):81–87. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.62150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murros KE, Huynh VA, Takala TM, Saris PE. Desulfovibrio bacteria are associated with Parkinson’s disease. Front Cell Infect Mi. 2021;11:652617. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.652617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin YC, Lin HF, Wu CC, Chen CL, Ni YH. Pathogenic effects of Desulfovibrio in the gut on lipid metabolism disorder in diet-induced obese mice and children with obesity. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57(11):913–925. doi: 10.1007/s00535-022-01909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bian X, Gao W, Wang Y, Yao Z, Xu Q, Guo C, et al. Riboflavin deficiency affects lipid metabolism partly by reducing apolipoprotein B100 synthesis in rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2019;70:5–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tóth F, Cseh EK, Vécsei L. Natural molecules and neuroprotection: kynurenic acid, pantethine and α-lipoic acid. Int T Mol Sci. 2021;22(1):403. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li M, Shu X, Xu H, Zhang C, Yang L, Zhang L, et al. Integrative analysis of metabolome and gut microbiota in diet-induced hyperlipidemic rats treated with berberine compounds. J Transl Med. 2016;14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0987-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cardoso DR, Libardi SH, Skibsted LH. Riboflavin as a photosensitizer. Effects on human health and food quality. Food Funct. 2012;3(5):487–502. doi: 10.1039/c2fo10246c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Averianova LA, Balabanova LA, Son OM, Podvolotskaya AB, Tekutyeva LA. Production of vitamin B2 (riboflavin) by microorganisms: an overview. Front Bioeng Biotech. 2020;8:1172. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.570828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henriques BJ, Olsen RK, Bross P, Gomes MC. Emerging roles for riboflavin in functional rescue of mitochondrial β-oxidation flavoenzymes. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(32):3842–3854. doi: 10.2174/092986710793205462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, Wang J, Zhou Y, Han H, Liu W, Li D, et al. Integrated omics analysis reveals differences in gut microbiota and gut-host metabolite profiles between obese and lean chickens. Poult Sci. 2022;101(11):102165. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang J, Wu Y, Zhang B, Liang S, Guo Z, Hu J, et al. Integrated liver proteomics and metabolomics identify metabolic pathways affected by pantothenic acid deficiency in Pekin ducks. Anim Nutr. 2022;11:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jungert A, McNulty H, Hoey L, Ward M, Strain JJ, Hughes CF, et al. Riboflavin is an important determinant of vitamin B-6 status in healthy adults. J nutr. 2020;150(10):2699–2706. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarrett H, McNulty H, Hughes CF, Pentieva K, Strain JJ, McCann A, et al. Vitamin B-6 and riboflavin, their metabolic interaction, and relationship with MTHFR genotype in adults aged 18–102 years. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;116(6):1767–1778. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Field MS, Bailey RL, Stover PJ. Unrecognized riboflavin deficiency and evidence for cascading effects on vitamin B-6 status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;116(6):1472–1473. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evans M, Rumberger JA, Azumano I, Napolitano JJ, Citrolo D, Kamiya T. Pantethine, a derivative of vitamin B5, favorably alters total, LDL and non-HDL cholesterol in low to moderate cardiovascular risk subjects eligible for statin therapy: a triple-blinded placebo and diet-controlled investigation. Vasc Health Risk Man. 2014;10:89–100. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S57116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rumberger JA, Napolitano J, Azumano I, Kamiya T, Evans M. Pantethine, a derivative of vitamin B5 used as a nutritional supplement, favorably alters low-density lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism in low–to moderate–cardiovascular risk North American subjects: a triple-blinded placebo and diet-controlled investigation. Nutr Res. 2011;31(8):608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Digel M, Ehehalt R, Stremmel W, Füllekrug J. Acyl-CoA synthetases: fatty acid uptake and metabolic channeling. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;326:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-0003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leonardi R, Jackowski S. Biosynthesis of pantothenic acid and coenzyme A. EcoSal Plus. 2007;2(2):10–1128. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.3.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kleinkauf H. The role of 4’-phosphopantetheine in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, polyketides and peptides. BioFactors. 2000;11:91–92. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520110126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen J, Li Y, Chen M, Liu X, Chen J, Li X, et al. Pantethine ameliorates recognition impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease by modulating cholesterol content and intestinal flora species. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2023;67(15):2200799. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202200799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCarty MF. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase by cystamine may mediate the hypotriglyceridemic activity of pantethine. Med hypotheses. 2001;56(3):314–317. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen YQ, Zhao SP, Zhao YH. Efficacy and tolerability of coenzyme A vs pantethine for the treatment of patients with hyperlipidemia: A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(5):692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hsu JC, Tanaka K, Ohtani S, Collado CM. Effects of pantethine supplementation to diets with different energy cereals on hepatic lipogenesis of laying hens. Poult Sci. 1987;66(2):280–288. doi: 10.3382/ps.0660280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Statistics of transcriptome sequencing for liver of aged laying hens. Table S2. Statistics of cecal microbiome sequencing of aged laying hens. Table S3. Numbers of taxa detected in cecal microbiome of aged laying hens. Fig. S1. (a) Ratio of successful annotation of ASVs in cecal microbiome of aged laying hens. (b) Variations in the alpha diversity of cecal microbiome of aged laying hens among different treatments. Fig. S2. Relative abundance of major bacterial phyla in cecum of aged laying hens. Fig. S3. Relative abundance of top 10 bacterial genera in cecal microbiome of aged laying hens fed by the LP and normal diets. Fig. S4. PCoA and adonis test based on the Bary-Curtis distance revealing the changes in cecal microbiome function between the CK and LL groups. Fig. S5. PCoA and adonis test based on the Bary-Curtis distance revealing the changes in cecal microbiome function related to metabolism, cellular processes, environmental information processing, and genetic information processing between the CK and LL groups. Fig. S6. Bacterial functions with significant variations in relative abundance in the cecum between the CK and LL groups (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05).

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the China National GeneBank Sequence Archive (CNSA) of the China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) with the accession number CNP0005028 and CNP0005031.