Abstract

In the galectin family, a group of lectins is united by their evolutionarily conserved carbohydrate recognition domains. These polypeptides play a role in various cellular processes and are implicated in disease mechanisms such as cancer, fibrosis, infection, and inflammation. Following synthesis in the cytosol, manifold interactions of galectins have been described both extracellularly and intracellularly. Extracellular galectins frequently engage with glycoproteins or glycolipids in a carbohydrate-dependent manner. Intracellularly, galectins bind to non-glycosylated proteins situated in distinct cellular compartments, each with multiple cellular functions. This diversity complicates attempts to form a comprehensive understanding of the role of galectin molecules within the cell. This review enumerates intracellular galectin interaction partners and outlines their involvement in cellular processes. The intricate connections between galectin functions and pathomechanisms are illustrated through discussions of intracellular galectin assemblies in immune and cancer cells. This underscores the imperative need to fully comprehend the interplay of galectins with the cellular machinery and to devise therapeutic strategies aimed at counteracting the establishment of galectin-based disease mechanisms.

Keywords: Galectin, Protein interaction, Immune cell, Cancer

Introduction

The glycome contains important biological information and in this way has a major impact on the cellular function and behaviour [1]. Cell tools for glycome manipulation employ glycosyl transferases, glycosidases and lectins. A β-galactoside binding lectin family are the galectins [2]. They have been found in multicellular organisms and can be detected intra- as well as extracellularly. Numerous functions attributed to galectins revolve around extracellular carbohydrate recognition, targeting either glycosylated membrane components or soluble ligands. However, it is noteworthy that galectins are synthesized in the cytosol, a cellular compartment where they can engage in specific interactions with various binding partners. In this intracellular environment, galectins establish connections with cellular entities, showcasing their versatility in influencing processes beyond the realm of extracellular carbohydrate recognition.

The galectin family

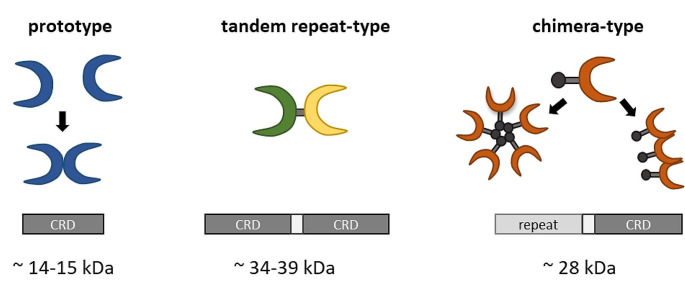

The first galectin was discovered 1975 in the electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) and was named electrolectin [3]. The term galectin was introduced in 1994 [2]. So far 19 galectin subtypes have been identified. These lectins share distinctive primary amino acid sequences and are characterized by containing one or two carbohydrate recognition domains (CRD). Based on the CRD-number and allocation, galectins were classified into three groups. Prototype galectins contain only one CRD domain and can dimerize by non-covalent binding (galectin-1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 16) (Fig. 1). Tandem repeat-type galectins are equipped with two distinct CRDs with individual sugar-binding capacities, which are linked by a stretch of 5 to 50 amino acids (galectin-4, 6, 8, 9 and 12). The sole member of the chimera-type galectins is galectin-3. This individual variant contains one CRD that is linked to a non-lectin proline-rich N-terminal domain. Galectins found in the human genome were classified by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee into galectin-1, -2, -3, -4, -7, -7B, -8, -9, -9B, 9 C, -10, -12, -13, -14, and − 16 (Gene group: Galectins (LGALS)).

Fig. 1.

Domain structure of galectin subtypes. Prototype galectins contain one CRD, galectin-1, -2, -5, -7, -10, -11, -13, -14 and − 16. They are often characterized by a dimeric quaternary structure. Tandem repeat-type galectin-4, -6, -8, -9 and 12 are characterized by two CRDs. The only chimera-type galectin with a dynamic proline/tyrosine/glycine-repeat N-terminal domain and one C-terminal CRD is galectin-3. Type-C and Type-N-self-association by the C- or N-terminal domain into oligomeric assemblies have been described

The CRD contains all amino acid residues associated with the carbohydrate binding and is assembled from two extended antiparallel β-sheets folded into a β-sandwich structure [4]. Phylogenetic CRD-analysis based on genomic and mRNA data revealed that galectins with two CRDs emerged from an original bi-CRD galectin, which arose by tandem duplication of the gene encoding the ancestral mono-CRD galectin [5]. The β-sandwich CRD structure is widespread and many viral glycan-binding proteins contain a similar structural architecture so that it is likely that these viral proteins originate from host lectins [6]. Galectins specifically interact with N-acetyllactosamine (LN, Galβ1,3GlcNAc or Galβ1,4GlcNAc), a component present in various N- or O-linked glycans found on proteins throughout the cell. The concentrations of lectins required for half-maximal saturation of LN-binding, also known as the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), typically range from ten to several hundred µM. For example, galectin-1 exhibits a Kd of 21.5 µM [7], galectin-2 has a Kd of 654 µM [8], Kds for galectin-3 range from 27.9 to 93 µM [8, 9], full length galectin-4 has a Kd of 9.3 µM [8] and galectin-7 has a Kd within the range of 270–410 µM [9]. Their affinity for binding to oligosaccharides is higher compared to monosaccharides, and this affinity increases with the number of glycans [10]. In general, galectin binding affinities for most oligosaccharidic structures is relatively low. This can be compensated by galectin-oligomerization to form multivalent interactions with target molecules [11]. Some galectins have a preferential tissue specific localization like galectin-7 in the skin, galectin-10 in eosinophils/regulatory T cells, galectin-12 in adipose tissue [12] and galectin-13, 14 as well as 16 in the placenta [13, 14]. Other galectins like galectin-1 and galectin-3 show a more ubiquitous distribution.

Here, we primarily focus on the interactions of galectins with distinct polypeptides in intracellular compartments under normal and pathological conditions.

Galectin interactions in the nucleus

Some galectins possess classical nuclear localization sequences, resulting in their translocation from the cytosol into the nucleus (see Fig. 2). Examples include murine galectin-3 with the sequence (253)ITLT(256) [15] and human galectin-3 with (223)HRVKKL(228) [16]. The latter interacts with importin-α to facilitate passage through nuclear pores (refer to Table 1). Murine galectin-3’s N-terminus also demonstrates active nuclear transport capabilities, featuring a leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) at positions 241–249 [17]. Significantly, the phosphorylation of galectin-3 at Ser-6 by casein kinase 1 (CK1) appears to be involved in its nuclear export and anti-apoptotic activity, as illustrated in Fig. 2 [18, 19]. Phosphorylated galectin-3 is translocated from the nucleus to the cytosol, providing protection to the cells against drug-induced apoptosis. Consequently, the phosphorylation of galectin-3 at Serine-6 functions as a molecular switch, regulating its cellular translocation from the nucleus to the cytosol. Additionally, the pool of nuclear galectin-3 is augmented by a proline to histidine substitution at position 64, observed in breast and gastric cancers, thereby promoting cancer progression [20, 21].

Fig. 2.

Intracellular binding partners of galectins in distinct cellular processes. Different cellular localizations and interaction partners of galectins are exemplified on a scheme depicting cellular organelles. Subtypes of prototype and tandem repeat galectins are indicated. E, endosome; LT, lactotransferrin; MVE, multivesicular endosome; SE, sorting endosome; V, transport vesicle

Table 1.

Intracellular galectin binding polypeptides

| nucleus | cytoplasm | vesicle lumen | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| galectin-1 | Gemin4 [24] | Bam32 [106] | ||

| TFII-I [30] | GRP78 [113] | |||

| H-Ras [44] | ||||

| PCDH24 [120] | ||||

| Raf effector [48] | ||||

| galectin-3 | c-Jun, Fra-1 [34] | 14-3-3σ [49] | CAECAM1, LPH, p75 [65] | |

| CK1 [18] | ALIX [93] | DPPIV, NHE2 [71] | ||

| CRM1 [17] | bcl-2 [101] | integrin-β1 [73] | ||

| Gemin4 [24] | c-Abl/ Arg [124, 125] | lactotransferrin [77] | ||

| hnRNPA2B1 [23] | CCDC50 [99] | podocalyxin [75] | ||

| HSF-1 [35] | hnRNP-L [32] | |||

| importin-α [16] | K-Ras [46] | |||

| snRNPU1 [25] | NuMa [51] | |||

| Sp1 [36] | OGT [54] | |||

| STAT3/ β-catenin [129] | PCDH24 [120] | |||

| TFII-I [30] | Syk [109] | |||

| TRIM16 [97] | ||||

| Tsg101 [57] | ||||

| galectin-4 | SNX3 [84] | DPPIV, CEA, NCA, CD59 [69] | ||

| Src/ SHP2 [55] | lamp2 [80] | |||

| transferrin receptor [79] | ||||

| vamp-3 [83] | ||||

| galectin-7 | Bcl-2 [132] | |||

| galectin-8 | mTOR [134] | |||

| NDP52 [88] | ||||

| galectin-9 | AMPK [134] | |||

| Rac1 [107] | ||||

| galectin-10 | RNS2/ RNS3 [85] | |||

| galectin-13 | HOXA1 [38] | annexin II [39] | ||

| galectin-14 | c-Rel [42] | |||

| galectin-16 | c-Rel [41] | |||

Within the nucleus, galectin-3 is localized in nuclear speckles, as evidenced by its co-localization with the Ser-, Arg-rich splicing factor SC35 [22, 23]. These nuclear dots, in terms of both number and size, resemble two subnuclear domains known as Cajal bodies and gems (coiled Cajal bodies). Galectin-3, along with galectin-1, interacts with the gem marker protein Gemin4 (Fig. 2), as demonstrated through GST pulldown or immunoprecipitation experiments [24, 25]. Both of these galectins play roles in nuclear splicing of pre-mRNAs and gene expression [26, 27]. They have been shown to function redundantly as splicing factors for mRNA processing and nuclear export [28]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), the knockdown of galectin-1 has a notable impact on the expression of angiogenesis-related genes [29]. Through interactome and transcriptome analysis in this study, it was revealed that galectin-1 serves as a potent regulator of alternative splicing patterns for angiogenesis-associated genes, particularly those involved in focal adhesion and the angiogenesis-associated vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. The lectin may influence the transcriptome profiles of HUVECs by binding to RNA transcripts. Notably, using a galectin-1 mutant deficient in carbohydrate binding, Voss et al. demonstrated that carbohydrate binding is not implicated in the interaction of galectin-1 with spliceosomal components [30].

The sequence of events in galectin-interactions in spliceosome assembly has been studied in detail for galectin-3. When splicing is initiated, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) assemble on the pre-mRNA to form the H complex (Fig. 2). One component of this complex is hnRNPA2B1, which interacts with galectin-3 [23]. If the N-terminal galectin-3-domain is added pre-mRNA splicing is arrested at a position corresponding to the H-complex, thus suggesting a functional role of galectin-3 in the first steps of splicing initiation [24]. Co-immunoprecipitation of galectin-3 from nuclear extracts also revealed components of the pre-spliceosome complexes E and A [23]. Evidence for interaction of galectin-3 with complex E came from earlier studies. This lectin fractionated in glycerol gradient separation studies from nuclear extracts in pre-mRNA particles together with the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) U1 thus forming a functional complex E [25, 31]. Galectin-3 itself is not a classical RNA-binding protein because it does not contain an RNA recognition motif [32]. Nevertheless, association of galectin-3 with snRNP U1 depends on the integrity of the snRNA of U1 and is affected in the presence of lactose. Together, these data strongly suggest that galectin-3 is involved in the initiation of spliceosome assembly and the splicing cascade.

In addition, mature mRNA can indirectly interact with galectin-3 in the perinuclear region. This has been demonstrated in pancreatic cancer cells, where the lectin binds to the hnRNP-L [32] (Fig. 2). It stabilizes the mRNA of the membrane-associated mucin MUC4, which activates genes involved in cell proliferation [33]. Expression of MUC2 is triggered by galectin-3 in intestinal cells by a different mechanism. Here, galectin-3 associates with c-Jun and Fra-1 in the nucleus to form an activating transcription factor complex at the AP-1 binding site on the MUC2 promoter [34]. Another example of galectin-3 as a transcription effector is provided by interaction with the HSF-1 transcription factor to promote expression of the cell adhesion molecule neogenin-1, cell survival in gastric cancer and cell motility [35](Fig. 2). Finally, involvement of galectin-3 in the cellular transcription machinery is demonstrated by its interaction with the transcription factor Sp1 in hematopoietic stem cells to upregulate p21 expression and control cell cycle progression [36].

Hox family proteins are transcription factors participating in embryonal development by gene expression regulation. Pull-down experiments revealed that placental galectin-13 binds to HOXA1, one of the earliest Hox genes to be expressed during embryonic development [37, 38]. HOXA1 can interact with the monomeric form of galectin-13 in the nucleus (Fig. 2). However, binding to dimeric galectin-13, which can be stabilized by disulphide bonds [39], is more efficient. It will be interesting to see future research on the consequences of this interaction on the cellular transcriptome especially in embryonic development. There is still another published nuclear galectin interaction that requires further characterization. With a sequence identity of about 60%, the two homologues prototype galectins galectin-14 and galectin-16 interact with the NF-κB family transcription factor c-Rel [40–42](Fig. 2). Consequences of this interaction may affect signal transduction, but the precise mechanistic details require further investigation.

Cytosolic galectin interactions and non-classical galectin secretion

The functions of galectins are diverse and involve intricate interactions within cellular processes. In cellular signalling, galectin-1 is crucial for the nanoclustering of the small GTPase H-Ras [43, 44], while galectin-3 plays a similar role for K-Ras [45–47](Fig. 2). These nanoclusters, although short-lived, assemble on the cytoplasmic membrane leaflet, influencing signaling cascades. Galectin-1 specifically binds to and stabilizes dimers of the Raf effector, positively regulating GTP-H-Ras nanoscale signaling hubs [48]. A recent atomistic structural model of the Ras-Raf signalosome, including galectin-3 and 14-3-3σ, provides structural insight into these interactions [49]. In one scenario, galectin-3, capable of associating with the lipid bilayer [50], caps the farnesyl group of K-Ras in a hydrophobic binding pocket, facilitating the membrane localization of K-Ras assemblies. Notably, there is no evidence suggesting the involvement of sugar moieties in these cytosolic galectin functions. Conversely, galectin-3 associates with the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) in a sugar-dependent fashion [51] (Fig. 2). NuMA is a key mitotic regulator crucial for spindle pole establishment and cohesion. A mutant NuMA form blocked in O-GlcNAc-glycosylation leads to aberrant spindle pole formation. This mutant does not co-immunoprecipitate galectin-3, which suggests that the galectin-3-NuMA interaction depends on O-GlcNAc glycosylation. The exact mechanism remains unclear as O-GlcNAc does not bind to galectin-3 by itself. The cytosolic interaction of galectin-3 with basal bodies and centrosomes is significant, as depletion or knockdown of galectin-3 results in microtubule disorganization, perturbation of epithelial morphogenesis, and disorganization of primary cilia [52] or motile respiratory kinocilia [53].

It is interesting to note that in Hela cells galectin-3 can by itself be O-GlcNAcylated in the cytoplasm by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) [54]. This glycan modification, rarely found on secreted galectin-3 polypeptides, suggests that O-GlcNAcylation might trigger export of the lectin from the cytoplasm into the extracellular milieu. Additionally, tyrosine-phosphorylation by members of the Src kinase family affects the secretion of galectin-4 [55].

In general, secretion of galectins does not involve the classical transport pathway starting at the rough endoplasmic reticulum followed by vesicular transport to the Golgi apparatus, the trans Golgi network and endosomal compartments up to the plasma membrane. Instead, they are secreted by so-called non-classical mechanisms. One non-classical secretion scenario describes the sorting of cargo by members of the endosomal complex required for transport (ESCRT) into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) at the membrane of multivesicular endosomes (MVEs) [56](Fig. 2). Galectin-3 interacts in the cytosol with Tsg101, a component of the ESCRT-I complex [57]. This direct interaction, facilitated by a highly conserved tetrapeptide P(S/T)AP motif (late domain motif) in the amino terminus of galectin-3, ensures recruitment into ILVs. The fusion of multivesicular endosomes (MVE) with the plasma membrane leads to the release of these vesicles as extracellular vesicles (EVs), functioning as communication platforms between cells or even organs within a living organism. The membrane protein E-cadherin is integrated into EV membranes through a comparable mechanism [58].

The primary secretion mechanism for galectin-3 from the apical membrane of polarized kidney epithelial cells is via EV-based secretion. Evidence for a functional role of cell-to-cell transfer of galectin-3-containing EVs comes from a study on the communication between B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells and stromal cells [59]. Fei et al. discovered that galectin-3 released from stromal cells is internalized by target cells and transported into the cell nucleus. This process induces galectin-3 expression and provides protection to the target cells against drug treatment.

While a late domain motif has not been identified in other galectin-family members, the presence of galectin-1 [60], galectin-4 [61], galectin-5 [62] galectin-9 [61] and galectin-13 [63] in extracellular vesicle pools suggests recruitment by yet unidentified mechanisms. Interaction of galectin-13 with cytosolic annexin II at the plasma membrane may play functional roles in the non-classical secretion of this lectin from placenta and fetal hepatic cells [39](Fig. 2). Alternative pathways for non-classical secretion of galectins are also under discussion. The interaction capacity of galectin-3 with membrane lipids suggests the possibility of spontaneous penetration of lipid bilayers [50]. The whole matter of non-classical secretion of galectins has not been settled yet and further studies are required to fully understand all processes involved. Notably, galectin-10 is released by eosinophil cells through a process of active cell death referred to as ETosis, elevating serum levels of galectin-10 [64]. This lytic degranulation of eosinophile cells elevates serum levels of galectin-10.

Galectin binding partners in endosomal, lysosomal or vesicular lumina

Galectins can be secreted and endocytosed or recruited into MVEs to reside within endosomes, lysosomes or transport vesicles, where they function as mechanistic components of vesicular trafficking. Internalized galectin-3, -4 and − 9 are involved in the apical endocytic-recycling of newly synthesized glycoproteins [65–69](Fig. 2). While being transported from the trans Golgi network (TGN) to the plasma membrane, galectin-3 binds to glycans that are exposed on the neurotrophin receptor. This binding leads to the clustering of the neurotrophin receptor, a non-raft-associated glycoprotein, into high molecular weight clusters. These clusters are then recruited into apical transport vesicles [70]. Galectin-3 is involved in apical targeting of the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CAECAM1), dipeptidylpeptidase IV (DPPIV), lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH), the neurotrophin receptor (p75), sodium-proton exchanger 2 (NHE2) and integrin-β1 [71–73]. A distinct set of lipid raft-associated apical cargo molecules is sorted by galectin-4 into apical transport carriers [66, 69]. In addition to binding to glycoproteins, the two carbohydrate recognition domains (CRDs) of galectin-4 interact specifically and with high affinity with a defined pool of glycosphingolipids. Specifically, this interaction involves sulfatides with long fatty acid chains, hydroxylated in position-2. The binding of galectin-4 to raft constituents results in cross-linking, forming raft clusters. These clusters are postulated to contribute to the formation of membrane microdomains that subsequently bud off to generate apical transport carriers. Once at the apical membrane, galectins can undergo re-internalization. It’s worth noting that the efficiency of galectin-3 internalization is pH-dependent and can be competitively inhibited by lactose [74]. Recent evidence indicates that the sialomucin podocalyxin establishes a ligand-receptor pair with galectin-3, initiating the co-internalization of both molecules from the apical membrane [75](Fig. 2). The endocytic process involves galectin-3-mediated cargo clustering and membrane bending, playing a functional role that is dependent on glycosphingolipids, as demonstrated in prior studies [76]. In mouse enterocytes, a glycosphingolipid-dependent internalization of lactoferrin and galectin-3 from the apical membrane has been previously described [77]. It also seems plausible that vesicular recycling of galectin-3 between the plasma membrane and endosomal organelles is maintained by alterations in the interaction partners. This view is supported by pH-dependent fine-tuning of galectin-3 cluster formation [78]. Moreover, the interaction between galectin-3 and integrin-β1, as well as galectin-4 with the transferrin receptor, facilitates basolateral to apical epithelial transcytosis [73, 79](Fig. 2). The elimination of these interactions results in the lysosomal targeting of the associated cargo molecules. This observation suggests that galectin-mediated apical sorting is not limited to newly synthesized cargo molecules but extends to previously existing ones as well.

Galectin-9 is enriched in the lumen of lysosomes from enterocytes and predominantly binds to the lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (Lamp2) [80](Fig. 2). This lectin interaction, largely with the N-glycan chain attached to Asn-175 of Lamp2, stabilizes lysosomes, maintains lysosomal acidity, and facilitates lysosome-mediated autophagy to prevent ER stress and associated cell apoptosis in intestinal Paneth cells and acinar cells of the pancreas. In dendritic cells, mast cells and macrophages galectin-9 is involved in cytokine secretion [81–83]. Intracellular galectin-9 interaction with the soluble NSF attachment receptor vesicle associated membrane protein 3 (VAMP3) regulates cytokine secretion in dendritic cells [83](Fig. 2). Interestingly, galectin-9 binds to the C-terminus of cytosolic sorting nexin-3 (SNX3) in macrophages to regulate compaction of intact Borrelia-containing phagosomes, thus driving their maturation and Borrelia degradation [84]. However, the exact role of galectin-9 in the curvature-sensitive process of Borrelia phagosome compaction is not known yet.

The Charcot-Leyden crystal component galectin-10 interacts with glycosylated human eosinophil granule cationic RNAses, namely, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (RNS2) and eosinophil cationic protein (RNS3), in a glycan-independent fashion [85]. Lectin-interaction does not inhibit the endoRNAses, but may play a role in their vesicular transport from granulogenesis until secretion in mature eosinophile cells.

Galectin binding involved in lysosomal damage

Recent evidence points on the involvement of galectins in lysosomal homeostasis. Lysosomes can be damaged by exposure to biologically active silica crystals, proteopathic fibrils or microbial invasion. Once damaged lysosomes are beyond repair, they are removed by autophagy (for review see [86]). In this process galectins in conjunction with ubiquitination serve as “eat me” signals to control orchestration of several autophagy regulators. They recognize membrane damage by binding to lumenal β-galactosides once glycoconjugates on the exofacial leaflet are exposed to the cytosol and bind to and recruit autophagic receptors. Initial publications of this phenomenon describe binding of galectin-3 to host glycans exposed on lysed vacuoles following Shigella, Listeria and Salmonella infection [87]. Thereafter, it was shown that galectin-3, -8 and − 9 sense the exposure of host glycans on membranes ruptured by Listeria, Salmonella and Shigella infection [88]. Mechanistic insight was provided by the finding that binding of the autophagic receptor NDP52 to the C-terminal CRD of galectin-8 and ubiquitin targets damaged Salmonella-containing vacuoles and activates antibacterial autophagy (Fig. 2). Moreover, in response to lysosomal damage galectin-8 dynamically associates with and inactivates the Ser/Thr protein kinase mTOR, which acts as a negative regulator by phosphorylating inhibitory sites on regulators of autophagy [89]. In conjunction with proximity biotinylation proteomics data these observations indicate that galectin-8 is a key regulatory node for lysophagy [90]. Galectin-9, which is also important for an optimal autophagic response, activates the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by displacement of the deubiquitinase USP9X from AMPK-TAK1-complexes to promote ubiquitination of TAK1 [89, 91]. The sequence of events in the action of galectin-3 on damaged lysosomes starts with targeting of the lectin to damage-exposed glycans. Here, interaction of the lectin with glycans exposed on the transferrin receptor (CD71) is functionally important for Gal3 recruitment to damaged lysosomes [92](Fig. 2). Galectin-3 then interacts with the ESCRT component ALG-2-interacting protein X (ALIX) [92–94] to facilitate ESCRT-III complex formation and mediate lysosomal repair [95, 96]. The intriguing aspect is that the interaction between galectin-3 and ALIX intensifies as lysosomal damage progresses. Simultaneously, the interaction with the ESCRT-I component Tsg101 decreases. This observation suggests a scenario in which ALIX selectively interacts with galectin-3 to facilitate lysosomal repair, while the association with Tsg101 aids in recruiting the lectin into multivesicular endosomes (MVEs) for extracellular vesicle (EV) secretion. At a later step, when damaged lysosomes have to be removed by autophagy, galectin-3 switches from ALIX to the tripartite motif protein TRIM16 [97]. Here, the CRD-domain of galectin-3 interacts with TRIM16 to recognise endomembrane damage and associate with the key autophagy regulators ATG16L1, ULK1 and Beclin 1. They govern cargo degradation in a highly precise process [98]. Very recently, interaction of galectin-3 with the lysophagy receptor coiled-coil domain-containing 50 (CCDC50) has been demonstrated to control lysosomal integrity and renewal [99]. This interaction may not be direct. In melanoma CCDC50 is upregulated and the galectin-3/CCDC50-mediated lysophagy mechanism supports tumour growth and, potentially, also works in other tumours. Thus, especially within the last decade many aspects in the complex network of galectin interaction partners in lysosomal damage and autophagy have been uncovered to yield a cohesive view of galectin activities in this field.

Intracellular galectin interactions in immune cells

Extracellular galectin-1 and galectin-3 are both inducing T cell apoptosis by interaction with glycoprotein receptors CD45 and CD71 on the cell surface, which weakens the T cell mediated immune response [100]. It is thus surprising that intracellular galectin-3 has the opposite effect on T cell apoptosis. In Jurkat cells the carbohydrate binding domain of galectin-3 intracellularly interacts with the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl-2 to suppress apoptosis and promote cell growth [101]. Furthermore, Mohammadpour et al. demonstrated that the expression of galectin-3 provides partial protection to T cells against apoptosis induced by IFN-γ [102]. It remains unclear whether this protection is contingent upon extracellular or intracellular interactions of galectin-3. Nevertheless, antiapoptotic galectin-3 function is consistent with its known anti-apoptotic role in other cell types, including cancer cells [103]. The study of Mohammadpour et al. also shows that galectin-3 acts as a negative regulator of T cell function and proliferation [102]. The conflicting impacts, with its antiapoptotic properties on one side and the dampening of the immune response on the other, highlight the nuanced role of galectin-3 in T cells. A documented attenuation of the immune response by intracellular galectin-3 has specifically been observed in activated T cells. Here, galectin-3 interaction with the ESCRT component ALIX is focussed to the stable contact region between T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) called the immunological synapse (IS) [93]. This cytoplasmic interaction may promote T cell receptor downregulation and T cell inactivation by attenuation of ALIX-mediated trafficking events. In addition, Kaur et al. describe an increase in intracellular galectin-3 upon activation of CD8+ T cells following herpesvirus infection in comparison to the secreted galectin-pool [104]. In activated CD8+ T cells, cytoplasmic galectin-3 is mobilized to the immunological synapse (IS), where it diminishes both their proliferation and cytokine production, thereby impeding T cell functions. In contrast, galectin-9 exerts a positive influence on the immune response. It is recruited intracellularly to the IS upon T cell activation and promotes T cell receptor signalling, which affects T cell differentiation and B cell responses [105]. The precise mechanism of this galectin-9 mediated function, however, has not been clarified yet. Dendritic cells express galectin-1 which intracellularly interacts with the cytoplasmic adaptor protein Bam32 once the cell has reached the mature state [106](Fig. 2). This interaction might modulate the stimulatory capacity of mature dendritic cells to activate CD8+ T cells. Moreover, galectin-9 is also expressed in dendritic cells and has been shown to organize the cortical actin cytoskeleton to optimize their phagocytic capacity [107]. Knockdown experiments suggest that the underlying mechanism is based on a galectin-9 mediated promotion of Rac1-GTP activation, which then reorganizes the actin cytoskeleton and affects membrane rigidity.

Intracellular interactions of galectin-3 also suppress immune responses in neutrophil and dendritic cells. In neutrophil cells galectin-3 inhibits the neutrophil ROS response to phorbol myristate acetate or zymosan stimulation and regulates the life span of neutrophils during virulent Toxoplasma infection [108]. Importantly, mechanistic insight into the role of galectin-3 in attenuation of neutrophil cells came from a subsequent study on phagocytosis of Candida [109]. Wu et al. found that galectin-3 physically interacts with the tyrosine kinase Syk (Fig. 2), which suppresses complement receptor 3 (CR3) downstream Syk-mediated ROS production and anti-Candida function of neutrophil cells. Another study with dendritic cells did not observe galectin-3 mediated effects on Syk-induced signalling after stimulation of dectin-1 or TLR4, two different classes of pattern recognition receptors that identify molecular components expressed on microbial pathogens [110]. Instead, they demonstrate that galectin-3 affects cytokine expression of dendritic cells to suppress T cell responses. These observations are in line with data from Leishmania infected knockout mice showing that galectin-3 deficiency leads to increased activation of the Notch signalling pathway, and enhanced production of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [111]. Some of the observed effects in these studies can be explained by extracellular interaction of galectin-3 with glycan moieties exposed on the extracellular receptor domains. Nevertheless, the finding that neither the presence of lactose nor the addition of recombinant galectin-3 to dendritic cell cultures affected cytokine production also suggests a contribution of intracellular galectin-3 mediated interactions.

Overall, these studies indicate that depending on the galectin-variant or interaction partners cytosolic association with galectins provides ambivalent characteristics that can either dampen or elevate the immune response.

Intracellular binding partners of galectins in cancer

Many of the described roles of galectins in cancer can be assigned to interactions in the extracellular milieu. Nevertheless, some examples show that intracellular galectin interactions determine the fate of cancer progression. Cytosolic interaction of galectin-1 with H-Ras as mentioned above, stabilizes anchorage of the complex on the cytoplasmic membrane leaflet and further activates downstream oncogenic pathways together with the Raf effector [112](Fig. 2). This oncogenic role of galectin-1 corresponds to the poor survival rate of patients with a high expression pattern of this galectin subtype in gastric cancer [113], lung cancer [114], renal cancer [115], hepatocellular carcinoma [116] and ovarian cancer [117]. Moreover, in the cytosol and the nucleus galectin-1 colocalizes with the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), most likely the cytosolic variant of this ER-chaperone [113](Fig. 2). GRP78, which is also known as BIP, is overexpressed in various cancer cells and contributes to tumour cell survival [118]. Molecular details of this interaction are only vaguely understood. Clues might come from the observation that GRP78 is closely related to and promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer cells [119], which is also affected by protocadherin-24 (PCDH24), another galectin-1 interacting polypeptide [120, 121].

In analogy to galectin-1, galectin-3 interaction with K-Ras mediates membrane localization, stabilizes the GTPase in its active state and presents composite interfaces to facilitate Raf binding [49, 122, 45–47]. The multifaceted roles of galectin-3 in cancer progression have been summarized by Thijjsen et al. [123]. Of notice, galectin-3 itself is posttranslationally modified in distinct cancer tissues. In human breast cancer cells, the non-receptor tyrosine kinases c-Abl/Arg directly interact with and phosphorylate the N-terminal domain of cytosolic galectin-3 (Fig. 2). This phosphorylation occurs at tyrosine residues 79, 107, and 118, with Tyr-107 identified as the primary phosphorylation site [124, 125]. Moreover, galectin-3 can undergo cleavage, likely extracellularly, at this site by the chymotrypsin-like serine protease prostate-specific antigen (PSA) [126]. The phosphorylation at Tyr-107, mediated by c-Abl, inhibits this cleavage process. Consequently, unphosphorylated galectin-3 secreted by non-cancerous prostate cells is susceptible to cleavage by PSA, leading to the removal of the N-terminal domain. This cleavage event has the potential to reduce oligomerization and lattice formation by galectin-3 [127]. Interestingly, phosphorylation also seems to determine the intracellular fate of galectin-3 in cancer cells. If c-Abl/Arg kinases are absent, intracellular galectin-3 is recruited into lysosomes and degraded [125].

As mentioned before, the serine/threonine kinase CK1 phosphorylates galectin-3 at Ser-6 (Fig. 2). Apart from modulation of the subcellular lectin distribution between the nucleus and the cytosol, this phosphorylation is also required for tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells [128]. Phosphorylated galectin-3 activates a non-classical caspase activation cascade through induction of PTEN expression and inactivation of the PI3K/Akt survival pathway. The precise mechanisms responsible for galectin-3-mediated PTEN expression remain unclear at present. However, it appears that these mechanisms are facilitated by nuclear interactions of the lectin with transcription factors and/or heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs). The possibility of an interaction between phosphorylated galectin-3 and PTEN cannot be ruled out either.

A different site of action for galectin-3 are the WNT/β-catenin and STAT3 signalling pathways (Fig. 2). Binding of galectin-3 to the transcription factor STAT3 enhances its Tyr-705 phosphorylation, leading to its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation in gastric cancer tissues [129]. Furthermore, galectin-3 expression is elevated by WNT/β-catenin signalling. The lectin also interacts with β-catenin and promotes its translocation into the nucleus for activation of target genes. This study suggests that galectin-3 mediates the crosstalk between WNT/β-catenin and STAT3 signalling in tumour progression. Consequently, increased expression and co-localization of β-catenin, pSTAT3, and galectin-3 in patients with advanced gastric cancer correlates with a poorer prognosis.

Intracellular interaction of galectin-13 with the transcription factor HOXA1 does not seem to be exclusively important for embryonic development but also appears to be involved in cancer progression, since upregulation of HOXA1 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer or hepatocellular carcinoma [130, 131].

For galectin-7, interaction with mitochondrial Bcl-2 is implicated in the regulation of apoptotic cell death of colon carcinoma cells [132]. Bcl-2, which resides in the outer mitochondrial membrane oriented towards the cytosol, directly interacts with galectin-7 and recruits the lectin independently of carbohydrate recognition to mitochondria (Fig. 2). Mitochondrial localization and intracellular functioning of galectin-7 in apoptosis had been previously reported [133]. Upon binding to Bcl-2 galectin-7 may act as a pro-apoptotic protein that assists in initiation of the apoptotic cascade in cancer cells.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The past three decades have witnessed a significant increase in the identified intracellular interaction partners of galectins. Obviously, the focus of many of these studies concentrates on prototype galectin-1 and chimeric galectin-3. This is most likely due to the ubiquitous expression of these two galectins in many distinct tissues. Nevertheless, even if we narrow down our attention on these two galectins, many of the cellular interactions and their consequences still require further elucidation, especially on the molecular level. With respect to the remaining members of the galectin family extensive analysis of their intracellular roles should not be neglected. Even if just a defined number of examples is discussed in this review, it is self-evident that each member of this family possesses its individual pattern of cytosolic binding partners that await to be identified. We will have to fully characterize this network and identify the molecular details to develop strategies to cure diseases associated with galectin functions.

Author contributions

Ralf Jacob had the idea of this review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Figures were designed by Lena Gorek. The two authors critically revised the work.

Funding

We are indebted to the countless scientists whose research provided the basis for this review. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no datasets were generated or analysed for this review article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Reily C, Stewart TJ, Renfrow MB, Novak J (2019) Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 15(6):346–366. 10.1038/s41581-019-0129-4 10.1038/s41581-019-0129-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barondes SH, Cooper DN, Gitt MA, Leffler H (1994) Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. JBiolChem 269(33):20807–20810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teichberg VI, Silman I, Beitsch DD, Resheff G (1975) A beta-D-galactoside binding protein from electric organ tissue of Electrophorus electricus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72(4):1383–1387. 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1383 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobsanov YD, Gitt MA, Leffler H, Barondes SH, Rini JM (1993) X-ray crystal structure of the human dimeric S-Lac lectin, L-14-II, in complex with lactose at 2.9-A resolution. J Biol Chem 268(36):27034–27038. 10.2210/pdb1hlc/pdb 10.2210/pdb1hlc/pdb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houzelstein D, Goncalves IR, Fadden AJ, Sidhu SS, Cooper DN, Drickamer K, Leffler H, Poirier F (2004) Phylogenetic analysis of the vertebrate galectin family. Mol Biol Evol 21(7):1177–1187. 10.1093/molbev/msh082 10.1093/molbev/msh082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Li F (2013) Structural analysis of the evolutionary origins of influenza virus hemagglutinin and other viral lectins. J Virol 87(7):4118–4120. 10.1128/JVI.03476-12 10.1128/JVI.03476-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stowell SR, Dias-Baruffi M, Penttila L, Renkonen O, Nyame AK, Cummings RD (2004) Human galectin-1 recognition of poly-N-acetyllactosamine and chimeric polysaccharides. Glycobiology 14(2):157–167. 10.1093/glycob/cwh018 10.1093/glycob/cwh018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sindrewicz P, Li X, Yates EA, Turnbull JE, Lian LY, Yu LG (2019) Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy reliably determines galectin-ligand interactions. Sci Rep 9(1):11851. 10.1038/s41598-019-47658-8 10.1038/s41598-019-47658-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh TJ, Lin HY, Tu Z, Huang BS, Wu SC, Lin CH (2015) Structural basis underlying the binding preference of human Galectins-1, -3 and – 7 for Galbeta1-3/4GlcNAc. PLoS ONE 10(5):e0125946. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125946 10.1371/journal.pone.0125946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirabayashi J, Hashidate T, Arata Y, Nishi N, Nakamura T, Hirashima M, Urashima T, Oka T, Futai M, Muller WE, Yagi F, Kasai K (2002) Oligosaccharide specificity of galectins: a search by frontal affinity chromatography. BiochimBiophysActa 1572(2–3):232–254 doi:S0304416502003112 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marino KV, Cagnoni AJ, Croci DO, Rabinovich GA (2023) Targeting galectin-driven regulatory circuits in cancer and fibrosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov 22(4):295–316. 10.1038/s41573-023-00636-2 10.1038/s41573-023-00636-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di LS, Sundblad V, Cerliani JP, Guardia CM, Estrin DA, Vasta GR, Rabinovich GA (2011) When galectins recognize glycans: from biochemistry to physiology and back again. Biochemistry 50(37):7842–7857. 10.1021/bi201121m[doi] 10.1021/bi201121m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visegrady B, Than NG, Kilar F, Sumegi B, Than GN, Bohn H (2001) Homology modelling and molecular dynamics studies of human placental tissue protein 13 (galectin-13). Protein Eng 14(11):875–880. 10.1093/protein/14.11.875 10.1093/protein/14.11.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Than NG, Romero R, Goodman M, Weckle A, Xing J, Dong Z, Xu Y, Tarquini F, Szilagyi A, Gal P, Hou Z, Tarca AL, Kim CJ, Kim JS, Haidarian S, Uddin M, Bohn H, Benirschke K, Santolaya-Forgas J, Grossman LI, Erez O, Hassan SS, Zavodszky P, Papp Z, Wildman DE (2009) A primate subfamily of galectins expressed at the maternal-fetal interface that promote immune cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(24):9731–9736. 10.1073/pnas.0903568106 10.1073/pnas.0903568106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson PJ, Li SY, Lohse AG, Vandergaast R, Verde E, Pearson A, Patterson RJ, Wang JL, Arnoys EJ (2006) Transport of galectin-3 between the nucleus and cytoplasm. I. conditions and signals for nuclear import. Glycobiology 16(7):602–611. 10.1093/glycob/cwj088 10.1093/glycob/cwj088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakahara S, Hogan V, Inohara H, Raz A (2006) Importin-mediated nuclear translocation of galectin-3. J Biol Chem 281(51):39649–39659. 10.1074/jbc.M608069200 10.1074/jbc.M608069200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsay YG, Lin NY, Voss PG, Patterson RJ, Wang JL (1999) Export of galectin-3 from nuclei of digitonin-permeabilized mouse 3T3 fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res 252(2):250–261. 10.1006/excr.1999.4643 10.1006/excr.1999.4643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takenaka Y, Fukumori T, Yoshii T, Oka N, Inohara H, Kim HR, Bresalier RS, Raz A (2004) Nuclear export of phosphorylated galectin-3 regulates its antiapoptotic activity in response to chemotherapeutic drugs. Mol Cell Biol 24(10):4395–4406. 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4395-4406.2004 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4395-4406.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huflejt ME, Turck CW, Lindstedt R, Barondes SH, Leffler H (1993) L-29, a soluble lactose-binding lectin, is phosphorylated on serine 6 and serine 12 in vivo and by casein kinase I. J Biol Chem 268(35):26712–26718 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)74371-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balan V, Nangia-Makker P, Schwartz AG, Jung YS, Tait L, Hogan V, Raz T, Wang Y, Yang ZQ, Wu GS, Guo Y, Li H, Abrams J, Couch FJ, Lingle WL, Lloyd RV, Ethier SP, Tainsky MA, Raz A (2008) Racial disparity in breast cancer and functional germ line mutation in galectin-3 (rs4644): a pilot study. Cancer Res 68(24):10045–10050. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3224 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SJ, Shin JY, Cheong TC, Choi IJ, Lee YS, Park SH, Chun KH (2011) Galectin-3 germline variant at position 191 enhances nuclear accumulation and activation of beta-catenin in gastric cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 28(8):743–750. 10.1007/s10585-011-9406-8 10.1007/s10585-011-9406-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voss PG, Wang JL (2023) Liquid-liquid phase separation: Galectin-3 in nuclear speckles and ribonucleoprotein complexes. Exp Cell Res 427(1):113571. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113571 10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fritsch K, Mernberger M, Nist A, Stiewe T, Brehm A, Jacob R (2016) Galectin-3 interacts with components of the nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex. BMC Cancer 16:502. 10.1186/s12885-016-2546-0 10.1186/s12885-016-2546-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JW, Voss PG, Grabski S, Wang JL, Patterson RJ (2001) Association of galectin-1 and galectin-3 with Gemin4 in complexes containing the SMN protein. Nucleic Acids Res 29(17):3595–3602. 10.1093/nar/29.17.3595 10.1093/nar/29.17.3595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haudek KC, Voss PG, Locascio LE, Wang JL, Patterson RJ (2009) A mechanism for incorporation of galectin-3 into the spliceosome through its association with U1 snRNP. Biochemistry 48(32):7705–7712. 10.1021/bi900071b 10.1021/bi900071b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dagher SF, Wang JL, Patterson RJ (1995) Identification of galectin-3 as a factor in pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92(4):1213–1217 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vyakarnam A, Dagher SF, Wang JL, Patterson RJ (1997) Evidence for a role for galectin-1 in pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol 17(8):4730–4737 10.1128/MCB.17.8.4730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Park JW, Wang JL, Patterson RJ (2006) Immunoprecipitation of spliceosomal RNAs by antisera to galectin-1 and galectin-3. Nucleic Acids Res 34(18):5166–5174. 10.1093/nar/gkl673 10.1093/nar/gkl673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei J, Wu Y, Sun Y, Chen D (2023) Galectin-1 regulates RNA expression and alternative splicing of angiogenic genes in HUVECs. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 28(4):74. 10.31083/j.fbl2804074 10.31083/j.fbl2804074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voss PG, Gray RM, Dickey SW, Wang W, Park JW, Kasai K, Hirabayashi J, Patterson RJ, Wang JL (2008) Dissociation of the carbohydrate-binding and splicing activities of galectin-1. Arch Biochem Biophys 478(1):18–25. 10.1016/j.abb.2008.07.003 10.1016/j.abb.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haudek KC, Voss PG, Wang JL, Patterson RJ (2016) A 10S galectin-3-U1 snRNP complex assembles into active spliceosomes. Nucleic Acids Res 44(13):6391–6397. 10.1093/nar/gkw303 10.1093/nar/gkw303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppin L, Vincent A, Frenois F, Duchene B, Lahdaoui F, Stechly L, Renaud F, Villenet C, Van Seuningen I, Leteurtre E, Dion J, Grandjean C, Poirier F, Figeac M, Delacour D, Porchet N, Pigny P (2017) Galectin-3 is a non-classic RNA binding protein that stabilizes the mucin MUC4 mRNA in the cytoplasm of cancer cells. Sci Rep 7:43927. 10.1038/srep43927 10.1038/srep43927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bafna S, Kaur S, Batra SK (2010) Membrane-bound mucins: the mechanistic basis for alterations in the growth and survival of cancer cells. Oncogene 29(20):2893–2904. 10.1038/onc.2010.87 10.1038/onc.2010.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song S, Byrd JC, Mazurek N, Liu K, Koo JS, Bresalier RS (2005) Galectin-3 modulates MUC2 mucin expression in human colon cancer cells at the level of transcription via AP-1 activation. Gastroenterology 129(5):1581–1591. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.002 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SJ, Wang YG, Lee HW, Kang HG, La SH, Choi IJ, Irimura T, Ro JY, Bresalier RS, Chun KH (2014) Up-regulation of neogenin-1 increases cell proliferation and motility in gastric cancer. Oncotarget 5(10):3386–3398. 10.18632/oncotarget.1960 10.18632/oncotarget.1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia W, Kong L, Kidoya H, Naito H, Muramatsu F, Hayashi Y, Hsieh HY, Yamakawa D, Hsu DK, Liu FT, Takakura N (2021) Indispensable role of Galectin-3 in promoting quiescence of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Commun 12(1):2118. 10.1038/s41467-021-22346-2 10.1038/s41467-021-22346-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang T, Yao Y, Wang X, Li Y, Si Y, Li X, Ayala GJ, Wang Y, Mayo KH, Tai G, Zhou Y, Su J (2020) Galectin-13/placental protein 13: redox-active disulfides as switches for regulating structure, function and cellular distribution. Glycobiology 30(2):120–129. 10.1093/glycob/cwz081 10.1093/glycob/cwz081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert B, Vandeputte J, Remacle S, Bergiers I, Simonis N, Twizere JC, Vidal M, Rezsohazy R (2012) Protein interactions of the transcription factor Hoxa1. BMC Dev Biol 12:29. 10.1186/1471-213X-12-29 10.1186/1471-213X-12-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Than NG, Pick E, Bellyei S, Szigeti A, Burger O, Berente Z, Janaky T, Boronkai A, Kliman H, Meiri H, Bohn H, Than GN, Sumegi B (2004) Functional analyses of placental protein 13/galectin-13. Eur J Biochem 271(6):1065–1078. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04004.x 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rolland T, Tasan M, Charloteaux B, Pevzner SJ, Zhong Q, Sahni N, Yi S, Lemmens I, Fontanillo C, Mosca R, Kamburov A, Ghiassian SD, Yang X, Ghamsari L, Balcha D, Begg BE, Braun P, Brehme M, Broly MP, Carvunis AR, Convery-Zupan D, Corominas R, Coulombe-Huntington J, Dann E, Dreze M, Dricot A, Fan C, Franzosa E, Gebreab F, Gutierrez BJ, Hardy MF, Jin M, Kang S, Kiros R, Lin GN, Luck K, MacWilliams A, Menche J, Murray RR, Palagi A, Poulin MM, Rambout X, Rasla J, Reichert P, Romero V, Ruyssinck E, Sahalie JM, Scholz A, Shah AA, Sharma A, Shen Y, Spirohn K, Tam S, Tejeda AO, Wanamaker SA, Twizere JC, Vega K, Walsh J, Cusick ME, Xia Y, Barabasi AL, Iakoucheva LM, Aloy P, De Las Rivas J, Tavernier J, Calderwood MA, Hill DE, Hao T, Roth FP, Vidal M (2014) A proteome-scale map of the human interactome network. Cell 159(5):1212–1226. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.050 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Si Y, Yao Y, Jaramillo Ayala G, Li X, Han Q, Zhang W, Xu X, Tai G, Mayo KH, Zhou Y, Su J (2021) Human galectin-16 has a pseudo ligand binding site and plays a role in regulating c-Rel-mediated lymphocyte activity. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 1865(1):129755. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2020.129755 10.1016/j.bbagen.2020.129755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Si Y, Li Y, Yang T, Li X, Ayala GJ, Mayo KH, Tai G, Su J, Zhou Y (2021) Structure-function studies of galectin-14, an important effector molecule in embryology. FEBS J 288(3):1041–1055. 10.1111/febs.15441 10.1111/febs.15441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belanis L, Plowman SJ, Rotblat B, Hancock JF, Kloog Y (2008) Galectin-1 is a novel structural component and a major regulator of h-ras nanoclusters. Mol Biol Cell 19(4):1404–1414. 10.1091/mbc.e07-10-1053 10.1091/mbc.e07-10-1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paz A, Haklai R, Elad-Sfadia G, Ballan E, Kloog Y (2001) Galectin-1 binds oncogenic H-Ras to mediate ras membrane anchorage and cell transformation. Oncogene 20(51):7486–7493. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204950 10.1038/sj.onc.1204950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shalom-Feuerstein R, Plowman SJ, Rotblat B, Ariotti N, Tian T, Hancock JF, Kloog Y (2008) K-ras nanoclustering is subverted by overexpression of the scaffold protein galectin-3. Cancer Res 68(16):6608–6616. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1117 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elad-Sfadia G, Haklai R, Balan E, Kloog Y (2004) Galectin-3 augments K-Ras activation and triggers a ras signal that attenuates ERK but not phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity. J Biol Chem 279(33):34922–34930. 10.1074/jbc.M312697200 10.1074/jbc.M312697200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashery U, Yizhar O, Rotblat B, Elad-Sfadia G, Barkan B, Haklai R, Kloog Y (2006) Spatiotemporal organization of Ras signaling: rasosomes and the galectin switch. Cell Mol Neurobiol 26(4–6):471–495. 10.1007/s10571-006-9059-3 10.1007/s10571-006-9059-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blazevits O, Mideksa YG, Solman M, Ligabue A, Ariotti N, Nakhaeizadeh H, Fansa EK, Papageorgiou AC, Wittinghofer A, Ahmadian MR, Abankwa D (2016) Galectin-1 dimers can scaffold raf-effectors to increase H-ras nanoclustering. Sci Rep 6:24165. 10.1038/srep24165 10.1038/srep24165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mysore VP, Zhou ZW, Ambrogio C, Li L, Kapp JN, Lu C, Wang Q, Tucker MR, Okoro JJ, Nagy-Davidescu G, Bai X, Pluckthun A, Janne PA, Westover KD, Shan Y, Shaw DE (2021) A structural model of a ras-raf signalosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 28(10):847–857. 10.1038/s41594-021-00667-6 10.1038/s41594-021-00667-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lukyanov P, Furtak V, Ochieng J (2005) Galectin-3 interacts with membrane lipids and penetrates the lipid bilayer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 338(2):1031–1036. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.033 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magescas J, Sengmanivong L, Viau A, Mayeux A, Dang T, Burtin M, Nilsson UJ, Leffler H, Poirier F, Terzi F, Delacour D (2017) Spindle Pole cohesion requires glycosylation-mediated localization of NuMA. Sci Rep 7(1):1474. 10.1038/s41598-017-01614-6 10.1038/s41598-017-01614-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koch A, Poirier F, Jacob R, Delacour D (2010) Galectin-3, a novel centrosome-associated protein, required for epithelial morphogenesis. MolBiolCell 21(2):219–231 doi:E09-03-0193 [pii];10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0193 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clare DK, Magescas J, Piolot T, Dumoux M, Vesque C, Pichard E, Dang T, Duvauchelle B, Poirier F, Delacour D (2014) Basal foot MTOC organizes pillar MTs required for coordination of beating cilia. Nat Commun 5:4888. 10.1038/ncomms5888 10.1038/ncomms5888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mathew MP, Abramowitz LK, Donaldson JG, Hanover JA (2022) Nutrient-responsive O-GlcNAcylation dynamically modulates the secretion of glycan-binding protein galectin 3. J Biol Chem 298(3):101743. 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101743 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ideo H, Hoshi I, Yamashita K, Sakamoto M (2013) Phosphorylation and externalization of galectin-4 is controlled by Src family kinases. Glycobiology 23(12):1452–1462. 10.1093/glycob/cwt073 10.1093/glycob/cwt073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hurley JH, Hanson PI (2010) Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT machinery: it’s all in the neck. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11(8):556–566. 10.1038/nrm2937 10.1038/nrm2937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Banfer S, Schneider D, Dewes J, Strauss MT, Freibert SA, Heimerl T, Maier UG, Elsasser HP, Jungmann R, Jacob R (2018) Molecular mechanism to recruit galectin-3 into multivesicular bodies for polarized exosomal secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(19):E4396–E4405. 10.1073/pnas.1718921115 10.1073/pnas.1718921115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banfer S, Kutscher S, Fleck F, Dienst M, Preusser C, Pogge von Strandmann E, Jacob R (2022) Late domain dependent E-cadherin recruitment into extracellular vesicles. Front Cell Dev Biol 10:878620. 10.3389/fcell.2022.878620 10.3389/fcell.2022.878620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fei F, Joo EJ, Tarighat SS, Schiffer I, Paz H, Fabbri M, Abdel-Azim H, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N (2015) B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and stromal cells communicate through Galectin-3. Oncotarget 6(13):11378–11394. 10.18632/oncotarget.3409 10.18632/oncotarget.3409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maybruck BT, Pfannenstiel LW, Diaz-Montero M, Gastman BR (2017) Tumor-derived exosomes induce CD8(+) T cell suppressors. J Immunother Cancer 5(1):65. 10.1186/s40425-017-0269-7 10.1186/s40425-017-0269-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayechu-Muruzabal V, de Boer M, Blokhuis B, Berends AJ, Garssen J, Kraneveld AD, Van’t Land B, Willemsen LEM (2022) Epithelial-derived galectin-9 containing exosomes contribute to the immunomodulatory effects promoted by 2’-fucosyllactose and short-chain galacto- and long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides. Front Immunol 13:1026031. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1026031 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1026031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anand PK (2010) Exosomal membrane molecules are potent immune response modulators. Commun Integr Biol 3(5):405–408. 10.4161/cib.3.5.12474 10.4161/cib.3.5.12474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Than NG, Abdul Rahman O, Magenheim R, Nagy B, Fule T, Hargitai B, Sammar M, Hupuczi P, Tarca AL, Szabo G, Kovalszky I, Meiri H, Sziller I, Rigo J Jr., Romero R, Papp Z (2008) Placental protein 13 (galectin-13) has decreased placental expression but increased shedding and maternal serum concentrations in patients presenting with preterm pre-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Virchows Arch 453(4):387–400. 10.1007/s00428-008-0658-x 10.1007/s00428-008-0658-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fukuchi M, Kamide Y, Ueki S, Miyabe Y, Konno Y, Oka N, Takeuchi H, Koyota S, Hirokawa M, Yamada T, Melo RCN, Weller PF, Taniguchi M (2021) Eosinophil ETosis-Mediated release of Galectin-10 in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 73(9):1683–1693. 10.1002/art.41727 10.1002/art.41727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delacour D, Cramm-Behrens CI, Drobecq H, Le Bivic A, Naim HY, Jacob R (2006) Requirement for galectin-3 in apical protein sorting. CurrBiol 16(4):408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delacour D, Gouyer V, Zanetta JP, Drobecq H, Leteurtre E, Grard G, Moreau-Hannedouche O, Maes E, Pons A, Andre S, Le Bivic A, Gabius HJ, Manninen A, Simons K, Huet G (2005) Galectin-4 and sulfatides in apical membrane trafficking in enterocyte-like cells. JCell Biol 169(3):491–501 10.1083/jcb.200407073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Straube T, von Honig MT, Greb E, Schneider C, Jacob D R (2013) PH-dependent recycling of galectin-3 at the apical membrane of epithelial cells. Traffic 14(9):1014–1027. 10.1111/tra.12086[doi] 10.1111/tra.12086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mishra R, Grzybek M, Niki T, Hirashima M, Simons K (2010) Galectin-9 trafficking regulates apical-basal polarity in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA 107(41):17633–17638 doi:1012424107 [pii]; 10.1073/pnas.1012424107 [doi] 10.1073/pnas.1012424107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stechly L, Morelle W, Dessein AF, Andre S, Grard G, Trinel D, Dejonghe MJ, Leteurtre E, Drobecq H, Trugnan G, Gabius HJ, Huet G (2009) Galectin-4-regulated delivery of glycoproteins to the brush border membrane of enterocyte-like cells. Traffic 10(4):438–450. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00882.x 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00882.x[doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delacour D, Greb C, Koch A, Salomonsson E, Leffler H, Le Bivic A, Jacob R (2007) Apical sorting by galectin-3-Dependent glycoprotein clustering. Traffic 8(4):379–388 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laiko M, Murtazina R, Malyukova I, Zhu C, Boedeker EC, Gutsal O, O’Malley R, Cole RN, Tarr PI, Murray KF, Kane A, Donowitz M, Kovbasnjuk O (2010) Shiga toxin 1 interaction with enterocytes causes apical protein mistargeting through the depletion of intracellular galectin-3. Exp Cell Res 316(4):657–666. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.09.002 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Delacour D, Koch A, Ackermann W, Eude-Le Parco I, Elsasser HP, Poirier F, Jacob R (2008) Loss of galectin-3 impairs membrane polarisation of mouse enterocytes in vivo. JCell Sci 121(Pt 4):458–465 10.1242/jcs.020800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Honig E, Ringer K, Dewes J, von Mach T, Kamm N, Kreitzer G, Jacob R (2018) Galectin-3 modulates the polarized surface delivery of beta1-integrin in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 131(11). 10.1242/jcs.213199 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Schneider D, Greb C, Koch A, Straube T, Elli A, Delacour D, Jacob R (2010) Trafficking of galectin-3 through endosomal organelles of polarized and non-polarized cells. EurJCell Biol 89(11):788–798. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.07.001 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.07.001[doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roman-Fernandez A, Mansour MA, Kugeratski FG, Anand J, Sandilands E, Galbraith L, Rakovic K, Freckmann EC, Cumming EM, Park J, Nikolatou K, Lilla S, Shaw R, Strachan D, Mason S, Patel R, McGarry L, Katoch A, Campbell KJ, Nixon C, Miller CJ, Leung HY, Le Quesne J, Norman JC, Zanivan S, Blyth K, Bryant DM (2023) Spatial regulation of the glycocalyx component podocalyxin is a switch for prometastatic function. Sci Adv 9(5):eabq1858. 10.1126/sciadv.abq1858 10.1126/sciadv.abq1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lakshminarayan R, Wunder C, Becken U, Howes MT, Benzing C, Arumugam S, Sales S, Ariotti N, Chambon V, Lamaze C, Loew D, Shevchenko A, Gaus K, Parton RG, Johannes L (2014) Galectin-3 drives glycosphingolipid-dependent biogenesis of clathrin-independent carriers. Nat Cell Biol 16(6):595–606. 10.1038/ncb2970 10.1038/ncb2970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ivashenka A, Wunder C, Chambon V, Sandhoff R, Jennemann R, Dransart E, Podsypanina K, Lombard B, Loew D, Lamaze C, Poirier F, Grone HJ, Johannes L, Shafaq-Zadah M (2021) Glycolipid-dependent and lectin-driven transcytosis in mouse enterocytes. Commun Biol 4(1):173. 10.1038/s42003-021-01693-2 10.1038/s42003-021-01693-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.von Mach T, Carlsson MC, Straube T, Nilsson U, Leffler H, Jacob R (2014) Ligand binding and complex formation of galectin-3 is modulated by pH variations. Biochem J 457(1):107–115. 10.1042/BJ20130933 10.1042/BJ20130933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perez Bay AE, Schreiner R, Benedicto I, Rodriguez-Boulan EJ (2014) Galectin-4-mediated transcytosis of transferrin receptor. J Cell Sci 127(Pt 20):4457–4469. 10.1242/jcs.153437 10.1242/jcs.153437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sudhakar JN, Lu HH, Chiang HY, Suen CS, Hwang MJ, Wu SY, Shen CN, Chang YM, Li FA, Liu FT, Shui JW (2020) Lumenal galectin-9-Lamp2 interaction regulates lysosome and autophagy to prevent pathogenesis in the intestine and pancreas. Nat Commun 11(1):4286. 10.1038/s41467-020-18102-7 10.1038/s41467-020-18102-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kojima R, Ohno T, Iikura M, Niki T, Hirashima M, Iwaya K, Tsuda H, Nonoyama S, Matsuda A, Saito H, Matsumoto K, Nakae S (2014) Galectin-9 enhances cytokine secretion, but suppresses survival and degranulation, in human mast cell line. PLoS ONE 9(1):e86106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086106 10.1371/journal.pone.0086106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lv R, Bao Q, Li Y (2017) Regulation of M1–type and M2–type macrophage polarization in RAW264.7 cells by Galectin–9. Mol Med Rep 16(6):9111–9119. 10.3892/mmr.2017.7719 10.3892/mmr.2017.7719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Santalla Mendez R, Rodgers Furones A, Classens R, Fedorova K, Haverdil M, Canela Capdevila M, van Duffelen A, Spruijt CG, Vermeulen M, Ter Beest M, van Spriel AB, Querol Cano L (2023) Galectin-9 interacts with Vamp-3 to regulate cytokine secretion in dendritic cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 80(10):306. 10.1007/s00018-023-04954-x 10.1007/s00018-023-04954-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klose M, Salloum JE, Gonschior H, Linder S (2019) SNX3 drives maturation of Borrelia phagosomes by forming a hub for PI(3)P, Rab5a, and galectin-9. J Cell Biol 218(9):3039–3059. 10.1083/jcb.201812106 10.1083/jcb.201812106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grozdanovic MM, Doyle CB, Liu L, Maybruck BT, Kwatia MA, Thiyagarajan N, Acharya KR, Ackerman SJ (2020) Charcot-Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 interacts with cationic ribonucleases and is required for eosinophil granulogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 146(2):377–389e310. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.013 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S (2013) Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 13(10):722–737. 10.1038/nri3532 10.1038/nri3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paz I, Sachse M, Dupont N, Mounier J, Cederfur C, Enninga J, Leffler H, Poirier F, Prevost MC, Lafont F, Sansonetti P (2010) Galectin-3, a marker for vacuole lysis by invasive pathogens. Cell Microbiol 12(4):530–544. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01415.x 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thurston TL, Wandel MP, von Muhlinen N, Foeglein A, Randow F (2012) Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature 482(7385):414–418. 10.1038/nature10744 10.1038/nature10744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jia J, Abudu YP, Claude-Taupin A, Gu Y, Kumar S, Choi SW, Peters R, Mudd MH, Allers L, Salemi M, Phinney B, Johansen T, Deretic V (2018) Galectins Control mTOR in response to endomembrane damage. Mol Cell 70(1):120–135e128. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.009 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eapen VV, Swarup S, Hoyer MJ, Paulo JA, Harper JW (2021) Quantitative proteomics reveals the selectivity of ubiquitin-binding autophagy receptors in the turnover of damaged lysosomes by lysophagy. Elife 10. 10.7554/eLife.72328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Jia J, Bissa B, Brecht L, Allers L, Choi SW, Gu Y, Zbinden M, Burge MR, Timmins G, Hallows K, Behrends C, Deretic V (2020) AMPK, a Regulator of Metabolism and Autophagy, is activated by Lysosomal Damage via a novel galectin-Directed Ubiquitin Signal Transduction System. Mol Cell 77(5):951–969e959. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.028 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jia J, Claude-Taupin A, Gu Y, Choi SW, Peters R, Bissa B, Mudd MH, Allers L, Pallikkuth S, Lidke KA, Salemi M, Phinney B, Mari M, Reggiori F, Deretic V (2020) Galectin-3 coordinates a Cellular System for Lysosomal Repair and removal. Dev Cell 52(1):69–87e68. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.025 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen HY, Fermin A, Vardhana S, Weng IC, Lo KF, Chang EY, Maverakis E, Yang RY, Hsu DK, Dustin ML, Liu FT (2009) Galectin-3 negatively regulates TCR-mediated CD4 + T-cell activation at the immunological synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(34):14496–14501. 10.1073/pnas.0903497106 10.1073/pnas.0903497106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang SF, Tsao CH, Lin YT, Hsu DK, Chiang ML, Lo CH, Chien FC, Chen P, Arthur Chen YM, Chen HY, Liu FT (2014) Galectin-3 promotes HIV-1 budding via association with Alix and Gag p6. Glycobiology 24(11):1022–1035. 10.1093/glycob/cwu064 10.1093/glycob/cwu064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Radulovic M, Schink KO, Wenzel EM, Nahse V, Bongiovanni A, Lafont F, Stenmark H (2018) ESCRT-mediated lysosome repair precedes lysophagy and promotes cell survival. EMBO J 37(21). 10.15252/embj.201899753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Skowyra ML, Schlesinger PH, Naismith TV, Hanson PI (2018) Triggered recruitment of ESCRT machinery promotes endolysosomal repair. Science 360(6384). 10.1126/science.aar5078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Chauhan S, Kumar S, Jain A, Ponpuak M, Mudd MH, Kimura T, Choi SW, Peters R, Mandell M, Bruun JA, Johansen T, Deretic V (2016) TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 co-direct autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis. Dev Cell 39(1):13–27. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.08.003 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kimura T, Mandell M, Deretic V (2016) Precision autophagy directed by receptor regulators - emerging examples within the TRIM family. J Cell Sci 129(5):881–891. 10.1242/jcs.163758 10.1242/jcs.163758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jia P, Tian T, Li Z, Wang Y, Lin Y, Zeng W, Ye Y, He M, Ni X, Pan J, Dong X, Huang J, Li CM, Guo D, Hou P (2023) CCDC50 promotes tumor growth through regulation of lysosome homeostasis. EMBO Rep 24(10):e56948. 10.15252/embr.202356948 10.15252/embr.202356948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stillman BN, Hsu DK, Pang M, Brewer CF, Johnson P, Liu FT, Baum LG (2006) Galectin-3 and galectin-1 bind distinct cell surface glycoprotein receptors to induce T cell death. J Immunol 176(2):778–789. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.778 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang RY, Hsu DK, Liu FT (1996) Expression of galectin-3 modulates T-cell growth and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93(13):6737–6742 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mohammadpour H, Tsuji T, MacDonald CR, Sarow JL, Rosenheck H, Daneshmandi S, Choi JE, Qiu J, Matsuzaki J, Witkiewicz AK, Attwood K, Blazar BR, Odunsi K, Repasky EA, McCarthy PL (2023) Galectin-3 expression in donor T cells reduces GvHD severity and lethality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cell Rep 42(3):112250. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112250 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fukumori T, Oka N, Takenaka Y, Nangia-Makker P, Elsamman E, Kasai T, Shono M, Kanayama HO, Ellerhorst J, Lotan R, Raz A (2006) Galectin-3 regulates mitochondrial stability and antiapoptotic function in response to anticancer drug in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 66(6):3114–3119. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3750 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kaur M, Kumar D, Butty V, Singh S, Esteban A, Fink GR, Ploegh HL, Sehrawat S (2018) Galectin-3 regulates gamma-Herpesvirus specific CD8 T cell immunity. iScience 9:101–119. 10.1016/j.isci.2018.10.013 10.1016/j.isci.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen HY, Wu YF, Chou FC, Wu YH, Yeh LT, Lin KI, Liu FT, Sytwu HK (2020) Intracellular Galectin-9 enhances proximal TCR Signaling and Potentiates Autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 204(5):1158–1172. 10.4049/jimmunol.1901114 10.4049/jimmunol.1901114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ortner D, Grabher D, Hermann M, Kremmer E, Hofer S, Heufler C (2011) The adaptor protein Bam32 in human dendritic cells participates in the regulation of MHC class I-induced CD8 + T cell activation. J Immunol 187(8):3972–3978. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003072 10.4049/jimmunol.1003072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Querol Cano L, Tagit O, Dolen Y, van Duffelen A, Dieltjes S, Buschow SI, Niki T, Hirashima M, Joosten B, van den Dries K, Cambi A, Figdor CG, van Spriel AB (2019) Intracellular Galectin-9 controls dendritic cell function by maintaining plasma membrane rigidity. iScience 22:240–255. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.11.019 10.1016/j.isci.2019.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Alves CM, Silva DA, Azzolini AE, Marzocchi-Machado CM, Carvalho JV, Pajuaba AC, Lucisano-Valim YM, Chammas R, Liu FT, Roque-Barreira MC, Mineo JR (2010) Galectin-3 plays a modulatory role in the life span and activation of murine neutrophils during early Toxoplasma gondii infection. Immunobiology 215(6):475–485. 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.08.001 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu SY, Huang JH, Chen WY, Chan YC, Lin CH, Chen YC, Liu FT, Wu-Hsieh BA (2017) Cell intrinsic Galectin-3 attenuates Neutrophil ROS-Dependent Killing of Candida by modulating CR3 downstream Syk activation. Front Immunol 8:48. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00048 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fermin Lee A, Chen HY, Wan L, Wu SY, Yu JS, Huang AC, Miaw SC, Hsu DK, Wu-Hsieh BA, Liu FT (2013) Galectin-3 modulates Th17 responses by regulating dendritic cell cytokines. Am J Pathol 183(4):1209–1222. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.017 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fermino ML, Dylon LS, Cecilio NT, Santos SN, Toscano MA, Dias-Baruffi M, Roque-Barreira MC, Rabinovich GA, Bernardes ES (2016) Lack of galectin-3 increases Jagged1/Notch activation in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and promotes dysregulation of T helper cell polarization. Mol Immunol 76:22–34. 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.06.005 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li ZL, Prakash P, Buck M (2018) A tug of War maintains a dynamic protein-membrane complex: Molecular Dynamics simulations of C-Raf RBD-CRD bound to K-Ras4B at an Anionic membrane. ACS Cent Sci 4(2):298–305. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00593 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang Q, Ali M, Wang Y, Sun QN, Zhu XD, Tang D, Wang W, Zhang CY, Zhou HH, Wang DR (2022) Galectin–1 binds GRP78 to promote the proliferation and metastasis of gastric cancer. Int J Oncol 61(5). 10.3892/ijo.2022.5431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Carlini MJ, Roitman P, Nunez M, Pallotta MG, Boggio G, Smith D, Salatino M, Joffe ED, Rabinovich GA, Puricelli LI (2014) Clinical relevance of galectin-1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer 84(1):73–78. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.016 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Huang CS, Tang SJ, Chung LY, Yu CP, Ho JY, Cha TL, Hsieh CC, Wang HH, Sun GH, Sun KH (2014) Galectin-1 upregulates CXCR4 to promote tumor progression and poor outcome in kidney cancer. J Am Soc Nephrol 25(7):1486–1495. 10.1681/ASN.2013070773 10.1681/ASN.2013070773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang PF, Li KS, Shen YH, Gao PT, Dong ZR, Cai JB, Zhang C, Huang XY, Tian MX, Hu ZQ, Gao DM, Fan J, Ke AW, Shi GM (2016) Galectin-1 induces hepatocellular carcinoma EMT and sorafenib resistance by activating FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling. Cell Death Dis 7(4):e2201. 10.1038/cddis.2015.324 10.1038/cddis.2015.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schulz H, Schmoeckel E, Kuhn C, Hofmann S, Mayr D, Mahner S, Jeschke U (2017) Galectins-1, -3, and – 7 are prognostic markers for Survival of Ovarian Cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci 18(6). 10.3390/ijms18061230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 118.Ibrahim IM, Abdelmalek DH, Elfiky AA (2019) GRP78: a cell’s response to stress. Life Sci 226:156–163. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.04.022 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sun LL, Chen CM, Zhang J, Wang J, Yang CZ, Lin LZ (2019) Glucose-regulated protein 78 signaling regulates Hypoxia-Induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 cells. Front Oncol 9:137. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00137 10.3389/fonc.2019.00137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ose R, Oharaa O, Nagase T (2012) Galectin-1 and Galectin-3 mediate protocadherin-24-Dependent membrane localization of beta-catenin in Colon cancer cell line HCT116. Curr Chem Genomics 6:18–26. 10.2174/1875397301206010018 10.2174/1875397301206010018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ose R, Yanagawa T, Ikeda S, Ohara O, Koga H (2009) PCDH24-induced contact inhibition involves downregulation of beta-catenin signaling. Mol Oncol 3(1):54–66. 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.10.005 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Levy R, Biran A, Poirier F, Raz A, Kloog Y (2011) Galectin-3 mediates cross-talk between K-Ras and Let-7c tumor suppressor microRNA. PLoS ONE 6(11):e27490. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027490 10.1371/journal.pone.0027490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Thijssen VL, Heusschen R, Caers J, Griffioen AW (2015) Galectin expression in cancer diagnosis and prognosis: a systematic review. Biochim Biophys Acta 1855(2):235–247. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.03.003 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]