Abstract

A template-dependent RNA polymerase has been used to determine the sequence elements in the 3′ untranslated region of tobacco mosaic virus RNA that are required for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis and binding to the RNA polymerase in vitro. Regions which were important for minus-strand synthesis were domain D1, which is equivalent to a tRNA acceptor arm; domain D2, which is similar to a tRNA anticodon arm; an upstream domain, D3; and a central core, C, which connects domains D1, D2, and D3 and determines their relative orientations. Mutational analysis of the 3′-terminal 4 nucleotides of domain D1 indicated the importance of the 3′-terminal CA sequence for minus-strand synthesis, with the sequence CCCA or GGCA giving the highest transcriptional efficiency. Several double-helical regions, but not their sequences, which are essential for forming pseudoknot and/or stem-loop structures in domains D1, D2, and D3 and the central core, C, were shown to be required for high template efficiency. Also important were a bulge sequence in the D2 stem-loop and, to a lesser extent, a loop sequence in a hairpin structure in domain D1. The sequence of the 3′ untranslated region upstream of domain D3 was not required for minus-strand synthesis. Template-RNA polymerase binding competition experiments showed that the highest-affinity RNA polymerase binding element region lay within a region comprising domain D2 and the central core, C, but domains D1 and D3 also bound to the RNA polymerase with lower affinity.

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is the type species of the Tobamovirus genus of plant viruses. Its positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome encodes four proteins (reviewed in references 3, 4, and 8). The 126-kDa protein, encoded by a 5′-proximal open reading frame (ORF), is translated from the genomic RNA. It has a domain in its N-terminal region with amino acid sequence motifs typical of methyltransferases, which is believed to be involved in the synthesis of the 5′ cap structure, and a domain in its C-terminal region with sequences typical of RNA helicases. The 183-kDa protein is translated by readthrough of a stop codon at the end of the ORF for the 126-kDa protein. In addition to the two domains which it shares with the 126-kDa protein, the 183-kDa protein has a domain in its C-terminal region with amino acid sequence motifs typical of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp). Both the 126- and 183-kDa proteins, which have been detected in isolated TMV replication complexes, are needed for efficient replication of TMV RNA. Recently a purified TMV RdRp was shown to contain a 126-kDa/183-kDa protein heterodimer (48). The role in TMV RNA replication of the excess 126-kDa protein which is produced in vivo is not known. TMV RNA also encodes a 30-kDa cell-to-cell movement protein and a 17.5-kDa capsid protein, which are translated from different 3′-coterminal subgenomic mRNAs.

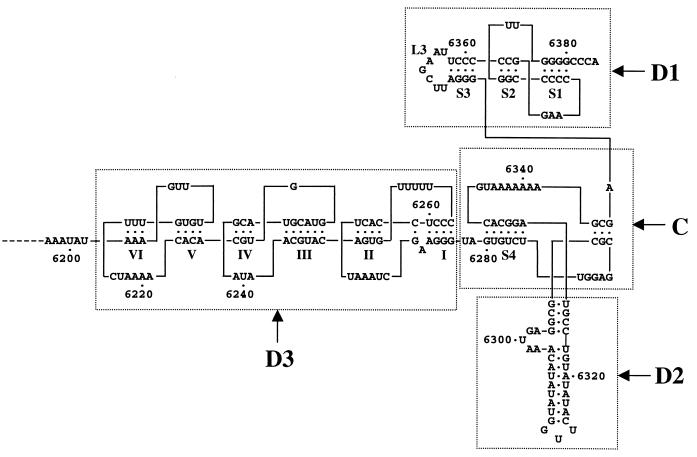

Replication of TMV RNA takes place in two stages: synthesis of a minus strand using the virus plus-strand RNA as a template is followed by synthesis of progeny plus strands using the minus strand as a template (3). Sequences in both the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of TMV plus-strand RNA are required for replication in vivo (9, 43, 44). The 3′-UTR can be folded into a tRNA-like structure (TLS) containing a 3′ pseudoknotted domain (D1) which mimics a tRNA acceptor branch terminating in an unpaired CCA sequence and a domain (D2) which resembles a tRNA anticodon branch (19, 47). A third upstream domain, D3, contains three pseudoknots, each of which contains two double-helical segments. Domains D1, D2, and D3 are connected by a pseudoknotted central core, C (Fig. 1). Mutational analysis of domain D3 has shown that double-helical segment I (closest to the TLS) is essential, and double-helical segment VI (furthest from the TLS) is dispensable, for replication of a tomato strain of TMV (TMV-L) in tobacco plants and protoplasts. Deletion of double-helical segments II to V reduced, but did not abolish, replication (43).

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the structure of the 3′-most 188 nucleotides of TMV-L RNA, modified from references 9, 43, and 47. Domains D1 to D3 and the central core (C) (all of which are boxed) are largely as defined in reference 19, except for the top 4 bp of the stem of domain D2, which were included in the central core (C) in reference 13.

The purpose of the present study was to determine which structural features of the TMV TLS and upstream domain D3 are required for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis. A potential problem with studies of cis-acting sequences in TMV replication in vivo in plants and protoplasts is that mutations may have pleiotropic effects. For example, parts of the TLS and domain D3 have been shown to be involved in the regulation of translation (28, 45). Therefore, mutations in the 3′-UTR may affect replication either directly or indirectly, via an effect on the translation of the 126- and 183-kDa proteins. Hence, although stem I in domain D3 is needed for TMV replication in vivo (43), it is not known whether it is required for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis.

The TMV 3′ TLS, like those of Brome mosaic virus (BMV) and Turnip yellow mosaic virus (TYMV), can be aminoacylated. TMV constructs containing the 3′-most 182 nucleotides (domains D1, D2, and D3), 108 nucleotides (domains D1 and D2), or 38 nucleotides (domain D1) are all substrates for yeast histidyl-tRNA synthetase (19). Whether aminoacylation is required for TMV replication in vivo is not known. However, by analogy with BMV and TYMV, aminoacylation is unlikely to be required for promotion of TMV minus-strand RNA synthesis. Experiments with BMV suggested that aminoacylation may be required for in vivo replication of RNA1 and RNA2, but not for in vivo replication of RNA3 (15–17, 36) or for minus-strand synthesis in vitro (14). For some TYMV mutants, there is a good correlation between aminoacylatability in vitro and genome amplification in vivo (46). However, aminoacylation is not an absolute requirement for in vivo replication of all tymoviruses, since TYMV chimeras containing the 3′ TLS of Erysimum latent virus, which cannot be aminoacylated, are infectious in plants and protoplasts (21) and aminoacylation is not required for TYMV minus-strand synthesis in vitro (11, 12, 39, 40). In a recent review, Dreher (13) concluded that “it is unlikely that aminoacylation is involved in promoting minus strand synthesis” for either BMV or TYMV.

One way to define the structural requirements for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis is to use in vitro systems, which have been widely employed for this purpose with both BMV and TYMV (6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 39, 40, 42). Recently, TMV RdRp preparations have been described which allow minus-strand RNA synthesis on defined templates in vitro in the absence of protein synthesis or aminoacylation and with high specificity (33, 48). Here we have used such an in vitro system to show that the D1, D2, and central core regions of the TLS are required for efficient TMV-L minus-strand RNA synthesis. We also confirm that double-helical segment I in domain D3 is needed for minus-strand synthesis, and we have used template competition experiments to define elements in the 3′-UTR which interact with the RdRp. This is the first in vitro analysis of the TMV promoter for minus-strand RNA synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RdRp reactions.

A membrane-bound RNA polymerase was isolated from TMV-L-infected tomato leaves and solubilized essentially as described previously (33, 34). Briefly, differential centrifugation of a leaf homogenate gave a 30,000 × g pellet containing the membrane-bound RNA polymerase, which was resuspended in buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.2], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol) and purified by centrifugation through sucrose density gradients in TED buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol). Fractions containing RNA polymerase activity from two sucrose gradients were diluted 10-fold with TED buffer and centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of buffer B. Sodium taurodeoxycholate (10% [wt/vol] solution) was added to give a final concentration of 1%, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 1 h with occasional gentle agitation. After centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h, the supernatant was dialyzed against buffer B. The RNA polymerase was made template dependent by removal of endogenous RNA template by addition of calcium acetate to a final concentration of 2 mM and BAL 31 nuclease (New England Biolabs) to a final concentration of 0.1 U/μl, followed by incubation at 30°C for 30 min. The BAL 31 nuclease was then inactivated by addition of EGTA to a final concentration of 5 mM and incubation on ice for 10 min. We have found BAL 31 to give more-reproducible template-dependent RNA polymerase preparations than micrococcal nuclease, which was used in our previous procedure (33), possibly due to variations in commercial batches of micrococcal nuclease. The BAL 31 procedure was adapted from a method developed to produce a template-dependent potato virus X RdRp (35). One hundred microliters of the template-dependent RNA polymerase and 25 μl of buffer B containing 4 mM ATP, 4 mM CTP, 4 mM GTP, 1 mM UTP, 20 μg of bentonite, and 10 μCi of [α32P]UTP (800 Ci/mmol) were mixed, and RNA template (1 μl) was then added to a final concentration of 12.5 nM. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The RNA product was isolated from reaction mixtures by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, resuspended in 10 μl of 95% deionized formamide–0.5 mM EDTA–0.025% xylene cyanol–0.025% bromophenol blue–0.025% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), heated to 95°C for 2 min, and analyzed by electrophoresis through denaturing 8% or 12% polyacrylamide-urea gels as described previously (23). The amount of label incorporated into newly synthesized RNAs was quantified with a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics). Product yields are expressed as percent molar yields, after correction for the various numbers of UMP residues per molecule of minus strand (labeled), compared to the yield of the control template t1. For template competition experiments, RNA polymerase reactions were carried out as above with control template t1 at 12.5 nM and various competitor RNAs at increasing concentration. Control template t1 and competitor RNA were mixed prior to addition to the RNA polymerase reaction mixture. Fifty-percent inhibitory concentrations, (IC50) were determined for each competitor as the molar concentration necessary to reduce minus-strand synthesis from template t1 by 50%.

Synthesis of RNA templates for the TMV-L RdRp.

PCR was used to generate cDNAs corresponding to all the RNA templates described. The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used for PCR are shown in Table 1. The forward primers, which all contained a T7 promoter at the 5′ end, and corresponding RNA templates (given in parentheses after the primer designation) (see Tables 2 to 4), were T4 (t45, t46), T26 (t1, t3, to t22), T400 (t2, t15a, t23 to t30, t32 to t38, t44), T401 (t39, to 40), T402 (t31), T403 (t41), T404 (t42), and T405 (t43). Reverse primers were T27 (t1, t2, t31 to t38, t40), T100 to T115 (t3 to t18, respectively), T112 (t15a), T118 (t23), T119 (t24), T120 (t25, t39), T121 (t45), T122 (t46), T123 (t44), T124 to T127 (t19 to t22, respectively), and T128 to T132 (t26 to t30 respectively). The DNA template for PCRs corresponding to RNA templates t1 to 31 and t39 to 46 was pTMV5, a full-length cDNA clone of TMV-L RNA (33). DNA templates for PCRs corresponding to RNA templates t32 to 38 were mutants produced (26) from a cloned KpnI-MluI fragment of pTMV5 in the pSL1180 vector (Pharmacia) using oligonucleotides T600 to T608, respectively. All PCRs were carried out using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and used as templates for in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion). RNA transcripts were purified as described in the Ambion manual and assayed spectrophotometrically.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequencea | TMV-L nucleotide positionsb |

|---|---|---|

| T4 | AGCTGACCCGGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGTATTTTTACAACAATTACC | 1–20 |

| T26 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTACTGGACTGTACAATCAG | 6108–6128 |

| T400 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGCTGAAATATAAAGTTTGTGTTTCTAAAACACACGTGG | 6190–6230 |

| T401 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTAGTGTCTTGGAGCGCGCGGAG | 6275–6299 |

| T402 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGAGGGATTCGAATTCCCCCGG | 6345–6365 |

| T403 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGTTTCCCTCCACTTAAATCGAAGGGTAGTGTC | 6254–6284 |

| T404 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGTTTCCCTCCACTTAAATCCATCCCTAGTGTCTTGGAGCGCGCGGAG | 6254–6304 |

| T405 | CGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGTTTGGGAGCACTTAAATCCATCCCTAGTGTCTTGGAGCGCGCGGAGTAAAC | 6254–6304 |

| T27 | TGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTC | c6384–6365 |

| T100 | GGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCG | c6383–6363 |

| T101 | GGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T102 | CGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T103 | AGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T104 | GGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGG | c6382–6362 |

| T105 | TTGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T106 | TAGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T107 | TCGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T108 | GCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGGG | c6381–6361 |

| T109 | TGTGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T110 | TGAGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T111 | TGCGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T112 | CCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGGGG | c6380–6360 |

| T113 | TGGTCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T114 | TGGACCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T115 | TGGCCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T118 | TGGGGGGGAACCGGGGGTTCCGGGGGAATTCG | c6384–6353 |

| T119 | TGGGGGGGAACCGCCCCTTCCGGGGGAATTCGAATCCCTCGC | c6384–6343 |

| T120 | TGGG|TCGCTTTTTTTACGTGCCTACGGACATATATGAACC | c6384–6381, 6346–6311c |

| T121 | ATTGTAGTTGTAGAATGTAAAATGTAATG | c73–45 |

| T122 | TGGG|ATTGTAGTTGTAGAATGTAAAATGTAATG | c6384–6381, 73–45c |

| T123 | TGGG|CCCTTCGATTTAAGTGGAGGGAAAAACAC | c6384–6381, 6277–6249c |

| T124 | CGCGTGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCG | c6384–6363 |

| T125 | TGCCCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T126 | TGCACCCCAACCGGGGGTTCC | c6384–6364 |

| T127 | CGCGTCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGGGG | c6380–6359 |

| T128 | TGGGCCCCAAGGCGGGGTTCCGGGGGAATTCGAATCCC | c6384–6347 |

| T129 | TGGGCCCCAAGGCGGGGTTCGCCGGGAATTCGAATCCCTCGCTTTTTTTACG | c6384–6333 |

| T130 | TGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGGCCCTATTCGAATCCCTCGCTTTTTTTACGTGCCTACG | c6384–6326 |

| T131 | TGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGGCCCTATTCGAAAGGGTCGCTTTTTTTACGTGCCTACGGACATATATGAACC | c6384–6311 |

| T132 | TGGGCCCCAACCGGGGGTTCCGGGGGATAAGCTTTCCCTCGCTTTTTTTACGTGCCTACGGACATATATG | c6384–6315 |

| T600 | CGAATCCCTCGCTTTTTTTACGTGCCT|GCGCTCCAAGACACTACCCTTCGATTTAAG | c6354–6328, 6293–6364c |

| T601 | CCGGGGGTTCCGGGGGAATTCGAATCCCT|TACCCTTCGATTTAAGTGGAGGGAAAAACAC | c6375–6346, 6279–6249c |

| T602 | GCCTACGGACATATATGAACCATATATGT|CCGCGCGCTCCATGACACTACCCTTCG | c6331–6303, 6297–6271c |

| T603 | CGAATCCCTCGCTTTTTTTACGTGCCTTGCCTGTATATACAACCATATATGTTTACTCCGCGCGCTC | c6354–6288 |

| T604 | TTTTTTACGTGCCTTGCCTGTATATACAACGTATATACATTACTGGCAGCGCTCCAAGACACTACCCTTCGATTTAAG | c6341–6264 |

| T607 | GGAATTCGAATCCCTCGCTTTTTTTACCACGGAACGGACATATATGAACCATATATG | c6360–6304 |

| T608 | AACCATATATGTTTACTCCGCGCGCTCCATCCGTGTACCCTTCGATTTAAGTGGAGGGAA | c6314–6255 |

Mutations in the TMV-L sequence are shown in bold. Non-TMV-L sequences are shown in italics. The T7 promoter sequence is underlined.

Numbers refer to the TMV-L sequence. Sequences complementary to the TMV-L sequence are prefixed with a “c”.

A vertical line (|) is used to indicate where the two parts of the sequence are linked.

TABLE 2.

Transcriptional efficiencies of templates with mutations at the 3′ terminus

| Template | 3′-terminal sequence of templatea | Mutation in 3′-terminal sequence | Relative efficiency (%)b | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t2 | GGGGCCCA | None (wild-type 3′ terminus) | 101.7 | 3.6 |

| t3 | GGGGCCC | 3′-terminal A (6384) deleted | <1 | |

| t4 | GGGGCCCC | 3′-terminal A→C | <1 | |

| t5 | GGGGCCCG | 3′-terminal A→G | <1 | |

| t6 | GGGGCCCU | 3′-terminal A→U | <1 | |

| t7 | GGGGCC | 3′-terminal CA deleted | <1 | |

| t8 | GGGGCCAA | Third C (6383)→A | 53.1 | 5.3 |

| t9 | GGGGCCUA | Third C (6383)→U | <1 | |

| t10 | GGGGCCGA | Third C (6383)→G | <1 | |

| t11 | GGGGC | 3′-terminal CCA deleted | <1 | |

| t12 | GGGGCACA | Second C (6382)→A | 54.6 | 1.1 |

| t13 | GGGGCUCA | Second C (6382)→U | 61.7 | 7.1 |

| t14 | GGGGCGCA | Second C (6382)→G | 53.4 | 2.7 |

| t15 | GGGG | 3′-terminal CCCA deleted | <1 | |

| t16 | GGGGACCA | First C (6381)→A | 56.2 | 2.9 |

| t17 | GGGGUCCA | First C (6381)→U | 58.1 | 4.0 |

| t18 | GGGGGCCA | First C (6381)→G | 56.8 | 4.0 |

| t19 | GGGGCCCACGCG | 3′-CGCG added | 103.3 | 5.9 |

| t20 | GGGGGGCA | First and second CC→GG | 100.7 | 2.6 |

| t21 | GGGGUGCA | First and second CC→UG | 55.8 | 2.0 |

| t22 | GGGGACGCG | First, second and third CCC deleted, 3′-CGCG added | <1 |

The control template (t1) corresponded to nucleotides 6108 to 6384 of TMV-L RNA. Template t2 corresponded to nucleotides 6190 to 6384 of TMV-L RNA. All other templates had the same sequence as t1 except for the 3′-terminal sequences shown. Mutations are shown in bold.

Compared to that of the control template t1. Values are averages of four determinations. Values of <1% are below the level of detection.

TABLE 4.

Transcriptional efficiencies of templates with mutations in domain D2 or D3 or the central core, C, or containing the 5′-UTR

| Template | Domain mutated | Mutation | Relative efficiency (%)b | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t32 | D2 | Δ6294–6327a | <1 | |

| t33 | C, D2 | Δ6280–6345a | <1 | |

| t34 | D2 | Δ6298–6302a | 23.7 | 1.3 |

| t35 | D2 | 6315CAUAUAUGUCCGU6327→GUAUAUACAGGCAa | <1 | |

| t36 | D2 | 6315CAUAUAUGUCCGU6327→GUAUAUACAGGCA, 6294GCGG6297→UGCC, and 6302ACAUAUAUG6311→UGUAUAUACa | 100.4 | 7.1 |

| t37 | C | 6328AGGCAC6333→UCCGUGa | 3.1 | 1.0 |

| t38 | C | 6328AGGCAC6333→UCCGUG and 6280GUGUCU6285→CACGGAa | 93.4 | 1.7 |

| t39 | D3, D1 | Δ6190–6274, Δ6347–6380a | <1 | |

| t40 | D3 | Δ6190–6274a | <1 | |

| t41 | D3 | Δ6190–6253a | 22.7 | 0.9 |

| t42 | D3 | Δ6190–6253, 6272GAAGGG6277→CAUCCCa | <1 | |

| t43 | D3 | Δ6190–6253, 6272GAAGGG6277→CAUCCC, and 6257CCCUC6261→GGGAGa | 31.4 | 1.8 |

| t44 | C, D1, D2 | Δ6278–6380a | <1 | |

| t45 | 1–73c | <1 | ||

| t46 | 1–73, 6381–6384c | <1 |

Mutations were made in template t2.

Compared to that of the control template, t1. Values are averages from four determinations. Values of <1% are below the level of detection.

TMV-L nucleotides included in the template.

Computer analysis.

Computer folding of some RNA sequences was modeled with the program mfold 3.1 (31, 49), available on the web site of M. Zuker (http://mfold2.wustl.edu).

RESULTS

Control templates and sensitivity of RdRp reactions.

Two RNA templates were used as controls. Template t1 corresponded to TMV-L nucleotides 6108 to 6384, which contains 75 nucleotides at the end of the coat protein gene together with the whole of the 202-nucleotide 3′-UTR. It has been shown to act as an efficient template for minus-strand RNA synthesis by the TMV-L RdRp (33). Template t2 corresponded to TMV-L nucleotides 6190 to 6384 and contains the whole of the 3′ tRNA-like region plus domain D3. RdRp reactions were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and [32P]UMP incorporation into bands was quantified with a phosphorimager. The amount of RdRp reaction product produced from template t2 was 101.7 ± 3.6% of that produced by the control template t1 (Table 2), indicating that the sequence between nucleotides 6108 and 6189, upstream of domain D3, had no significant effect on minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro. Mutations were made in template t1 or t2, and the amount of product formed with a mutant template was expressed as a percentage of the amount of product formed with the control template. Corrections were made for the number of U's in the product, assuming that the 3′-terminal A was not transcribed (33). The sensitivity of the standard assay was tested by making serial dilutions of the product from the control template, prior to analysis by PAGE and quantification. It was found that the minimum amount of product that could be detected in a standard assay was 1% of the undiluted control product. For reaction products, predicted to contain fewer U's than the control product, the amount of [32P]UTP in the reaction was increased proportionately to keep the sensitivity constant.

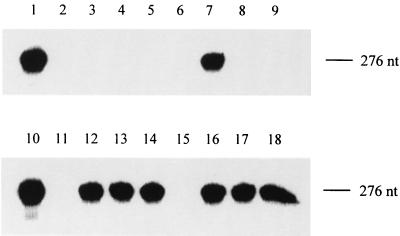

Mutational analysis of the 3′-terminal CCCA sequence.

To assess the importance of the 3′-terminal CCCA sequence, each of these four nucleotides was mutated to each of the other three. In addition, the effects of deleting the terminal A and of adding a 4-nucleotide CGCG extension were monitored. The results are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. It is clear that the greatest efficiency of transcription was obtained with a template terminating in CCCA or GGCA. We have previously shown that minus-strand RNA synthesis on a TMV-L template starts with a G, probably corresponding to the C adjacent to the 3′-terminal A of the template (33). Mutation of the first or second C to A, G, or U (templates t16 to t18, t12 to t14), mutation of the first and second C's together to UG (t21), or mutation of the third C to A (t8) reduced the transcriptional efficiency of the template by less than 50%, indicating that a 3′-terminal CA sequence may be necessary to direct RNA synthesis from a C closest to the 3′ end. Addition of a 4-base CGCG extension to the 3′ terminus of the control template (t19) did not significantly affect its transcriptional efficiency, consistent with results obtained with minus-strand synthesis directed by other positive-strand RNA viruses (2). Deletion of the 3′-terminal A (t3), CA (t7), CCA (t11), or CCCA (t15), simultaneous deletion of CCC and addition of CGCG (t22), or mutation of the terminal A to C, G, or U (t4 to t6), or of the third C to G or U (t9, t10), reduced the transcriptional efficiency of the template to less than 1% of that of the control template t1, confirming the requirement for a CA sequence at or near the 3′ end.

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional efficiencies of templates with mutations in the four 3′-terminal nucleotides. Templates were as follows: lane 1, t1; lane 2, t3; lane 3, t4; lane 4, t5; lane 5, t6; lane 6, t7; lane 7, t8; lane 8, t9; lane 9, t10; lane 10, t1; lane 11, t11; lane 12, t12; lane 13, t13; lane 14, t14; lane 15, t15; lane 16, t16; lane 17, t17; lane 18, t18. The mutations in each template are shown in Table 2. RNA polymerase reactions were carried out in the presence of [32P]UTP, and the products were separated by electrophoresis through denaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels. The position of the 276-nucleotide product expected from the control template t1 is indicated. The bands were detected using a phosphorimager.

Features of domain D1 required for minus-strand RNA synthesis.

Domain D1 contains a pseudoknot structure with two double-helical stems, S1 and S2 (Fig. 1). Upstream of the pseudoknot is another double-helical stem, S3, with an associated loop, L3 (Fig. 1). The results of making mutations to alter these structures are shown in Table 3. Template t25, which had nucleotides 6347 to 6380 deleted to remove domain D1 except for the CCCA 3′ terminus, had no detectable template activity for the TMV-L RdRp. This indicates that at least part of the structure of domain D1 is necessary for template activity. To determine if the S1 stem is needed for template activity, the four GC base pairs were disrupted by mutating all the G's to C's. The resultant mutant (t23) had no detectable template activity. Compensatory mutations of the four C's to G's to re-form the four GC base pairs but with the G and C positions reversed (t24) restored the template activity to just under half that of the control template. Mutations designed to disrupt stem S2 also greatly reduced template efficiency (t26), which was largely restored by the compensatory mutations (t27). Taken together, these results indicate that the pseudoknot stucture is important for template transcriptional efficiency. Mutations designed to disrupt the S3 stem (t28) reduced template activity to about 38% of that of the wild-type, and template activity was restored by compensatory mutations designed to re-form the stem (t29). Alteration of all the bases in the L3 loop also reduced template activity by half (t30), possibly as a result of disruption of proposed tertiary interactions between 6352UC6353 in the L3 loop (analogous to a T loop in canonical tRNAs) and 6287GG6288 in a single-stranded RNA region of the central core, C (analogous to a D loop in canonical tRNAs [19]). Template t31, which contained domain D1 together with the 3′ CCCA terminus, but from which domains D2 and D3 and the central core, C, had been deleted, had no detectable template activity.

TABLE 3.

Effects of mutations in the D1 domain on template transcriptional efficiencies

| Transcript | Mutationa | Relative efficiency (%)b | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| t23 | 6377GGGG6380→CCCC | <1 | |

| t24 | 6377GGGG6380→CCCC and 6368CCCC6371→GGGG | 58.3 | 6.6 |

| t25 | Δ6347–6380 | <1 | |

| t26 | 6372CGG6374→GCC | <1 | |

| t27 | 6372CGG6374→GCC and 6362CCG6364→GGC | 77.9 | 5.2 |

| t28 | 6358UCCC6361→AGGG | 38.3 | 3.4 |

| t29 | 6358UCCC6361→AGGG and 6347GGGA6350→CCCU | 96.0 | 5.9 |

| t30 | 6351UUCGAAU6357→AAGCUUA | 50.1 | 3.7 |

| t31 | Δ6190–6344 | <1 |

Mutations were made in template t2.

Compared to that of the control template, t1. Values are averages from four determinations. Values of <1% are below the level of detection.

Domain 2 and the central core, C, are necessary for minus-strand RNA synthesis.

The effects of mutations in domain D2 and the central core, C, on template transcriptional efficiencies are shown in Table 4. Deletion of domain D2 plus the central core region, C (t33) or of domain D2 alone (t32) abolished detectable template activity. Domain D2 consists of a stem-loop structure with a 5-nucleotide bulge in the 5′ strand of the stem (Fig. 1). Removal of the bulge sequence to create a completely base-paired 11-bp stem (t34) reduced minus-strand RNA synthesis to about 24% that of the wild type. A mutation which disrupted the D2 stem structure (t35) abolished detectable template activity. Analysis of the mutated D2 stem sequence with the mfold program (31, 49) indicated that the top part of the stem is completely disrupted, although some double-helical structure is possible in the lower part of the stem with several alternative structures of low stability (ΔG,−3.1 to −2.5 kcal/mol) compared to that of the wild-type D2 stem-loop (ΔG, −9.8 kcal/mol). Compensatory mutations designed to completely re-form the stem, but keeping the 5-nucleotide bulge sequence unchanged (t36) (calculated ΔG, −10.8 kcal/mol), restored the template activity to about that of the wild type. Hence the D2 stem structure is important for template activity.

The central core, C, consists of single-stranded regions and double-helical regions (Fig. 1). Disruption of the 6-bp double-helical region S4 (t37) reduced the template activity to about 3% of that of the wild-type, and re-formation of the double-helical structure by compensatory mutations (t38) restored template efficiency to almost wild-type levels, indicating that this structural feature of the central core region is important for template activity. A template consisting of only domain D2 and the central core region, linked to a 3′ CCCA sequence (t39) had less than 1% of the template activity of the control template, t1.

Effects of mutations in domain D3 on minus-strand RNA synthesis.

The effects of mutations in domain D3 on template activity are shown in Table 4. Domain D3 can be regarded as three stem-loop structures with three pseudoknots, giving six double-helical segments which have been named I to VI (43) (Fig. 1). Deletion of most of domain D3 (t40) resulted in loss of detectable template activity. Deletion of double-helical segments II to VI, while retaining double-helical segment I (t41), reduced template efficiency to about 23% of that of the control wild-type template. However, a further mutation of 5 nucleotides designed to disrupt all the base pairs in double-helical segment I (t42) abolished detectable template activity. Compensatory mutations designed to re-form the double-helical structure, but with bases on each strand complementary to those of the wild type (t43), increased the transcriptional efficiency of the template to about 38% higher than the level of t41. An RNA consisting of only domain D3 linked to a 3′ CCCA sequence (t44) had no detectable template activity.

Absence of initiation from internal CA or CCA sequences.

We have previously shown that a 392-nucleotide 5′ fragment of TMV-L RNA did not produce a detectable product in an RdRp assay (33), excluding the possibility of end-to-end copying. However, as the product was analyzed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel, it is possible that very small products, due to internal initiation, might have run off the end of the gel. Therefore, we have tested for internal initiation of minus-strand RNA synthesis with a template (t45) containing the 5′-UTR of TMV-L RNA. This sequence has many internal CA sequences, including a CCA sequence. When analyzed on denaturing 12% polyacrylamide gels capable of detecting products of less than 10 nucleotides, no product was detected in reactions containing t45 (Table 4). Addition of a 3′-terminal CCCA sequence to the 5′-UTR (t46) did not result in detectable template activity (Table 4).

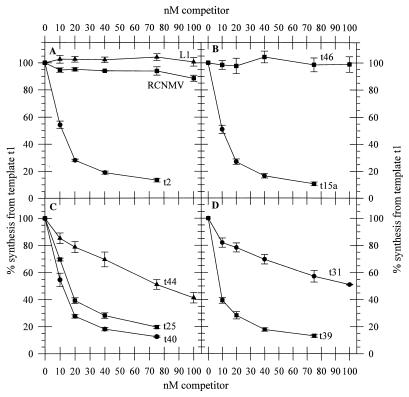

Structural elements which interact with the RdRp.

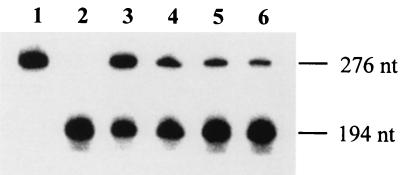

A template competition assay (6, 37, 38) was used to identify structural elements in the 3′-UTR required for interaction with the RdRp in comparison with those required for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis. The amount of product generated with control template t1 was quantified in the presence of increasing amounts of competitor RNA, and the IC50 (the molar concentration of competitor necessary to reduce synthesis from t1 by 50%) was determined. To establish the efficacy of the assay, control template t2 was used as a competitor. Templates t1 and t2 direct the synthesis of 276- and 194-nucleotide products, respectively (assuming that synthesis initiates at the penultimate C of the template), which are readily separated by PAGE. As expected, t2 was an efficient competitor with an IC50 of 12.0 nM (Fig. 3 and 4A; Table 5). In contrast, an RNA corresponding to the 3′-most 273 nucleotides of red clover necrotic mosaic virus (RCNMV) RNA 2 was a poor competitor, having only a slight effect on minus-strand RNA synthesis directed by template t1 at concentrations up to 100 nM (Fig. 4A; Table 5). RCNMV RNA is not a template for the TMV-L RNA polymerase (33). Another nonspecific RNA, L1, corresponding to nucleotides 2466 to 2738 of the cloning vector LITMUS 28 (New England Biolabs), had a negligible effect on RNA synthesis directed by t1 (Fig. 4A; Table 5). Hence it appears that only RNAs specific to TMV can compete with t1 for interaction with the TMV-L. RdRp.

FIG. 3.

Competition of control templates t1 and t2 for binding to the TMV-L RdRp. RNA polymerase reactions were carried out in the presence of [32P]UTP, and control templates t1 and/or t2 were used at the concentrations indicated. Lane 1, t1 alone (12.5 nM); lane 2, t2 alone (12.5 nM); lane 3, t1 (12.5 nM) and, t2 (10 nM); lane 4, t1 (12.5 nM) and t2 (20 nM); lane 5, t1 (12.5 nM) and t2 (40 nM); lane 6, t1 (12.5 nM) and t2 (75 nM). The products were separated by electrophoresis through denaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels and detected using a phosphorimager. The positions of the 276- and 194-nucleotide products expected from templates t1 and t2, respectively, are shown.

FIG. 4.

Template-RdRp binding competition. RNA polymerase reactions were carried out in the presence of [32P]UTP, 12.5 nM control template t1, and various concentrations of the competitor RNAs as, indicated. The products were separated by electrophoresis through denaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels, and the amounts of 276-nucleotide product formed from template t1 were quantified using a phosphorimager. Results are expressed as percentages of the amount of product formed from template t1 in the absence of competitor RNA. All points on the graphs are the averages of four experiments. Error bars, standard errors.

TABLE 5.

IC50 of competitor RNAs

| Competitor | IC50a (nM) |

|---|---|

| RCNMVb | >100 |

| L1 | >100 |

| t2 | 12.0 |

| t15a | 10.5 |

| t25 | 16.6 |

| t31 | >100 |

| t34 | 62.0 |

| t35 | 94 |

| t37 | >100 |

| t39 | 8.2 |

| t40 | 11.9 |

| t44 | 78.0 |

| t45 | >100 |

Defined as the molar concentration of competitor necessary to reduce minus-strand synthesis from template t1 by 50%.

The 3′-most 273 nucleotides of RCNMV RNA 2.

RNA t2 acts as an efficient competitor and also a template for the TMV-L RdRp. It was therefore of interest to determine if TMV-L RNAs with mutations in the 3′-UTR, which do not act as templates for the RdRp, can competitively bind to the RdRp. We first tested a 191-nucleotide RNA, t15a, which has the same sequence as t2, but lacks the 3′ CCCA terminus. The 273-nucleotide RNA, t15, which has the same sequence as t1, but lacks the 3′ CCCA terminus, was shown to have no detectable template activity (Table 2), and therefore it was considered likely that t15a also would not be a template for the RdRp. RNA t15a was shown to be an efficient competitor of RNA synthesis, with a competition profile comparable to that of t2 (Fig. 4B) and an IC50 of 10.5 nM (Table 5). Analysis of the product of the RdRp reactions by PAGE indicated that no detectable RNA synthesis directed by t15a had occurred even at 100 nM (data not shown). Hence t15a can bind to the RdRp in the absence of RNA synthesis directed by that RNA, and the 3′-terminal CCCA sequence is not required for the RNA binding. Furthermore, t46, which contains the TMV-L 5′-terminal 73 nucleotides linked to a 3′-terminal CCCA sequence, had no significant effect on minus-strand RNA synthesis directed by template t1 at concentrations up to 100 nM (Fig. 4B; Table 5), indicating that the CCCA sequence, or any of the multiple internal CA sequences in t46, did not compete significantly with t1 for RdRp binding.

Other effective competitors, which themselves did not direct detectable minus-strand RNA synthesis, were t40, which contains domains D1 and D2 and the central core, C (IC50, 11.9 nM) (Fig. 4C; Table 5); t25, which contains domains D2 and D3 and the central core, C (IC50, 16.6 nM) (Fig. 4C; Table 5); and t39, which contains domain D2 and the central core C (IC50, 8.2 nM) (Fig. 4D; Table 5). RNA t37, in which the stem S4 in the central core, C, is disrupted, was a very poor competitor (IC50, >100 nM) (Table 5) with a profile similar to those of the nonspecific RNAs (L1 and the RCNMV 3′ end [Fig. 4]). RNA t44, which contains domain D3, RNA t31, which contains domain D1, and RNA t35, in which the stem of domain D2 is disrupted, were relatively poor competitors (IC50, 78, >100, and 94 nM, respectively) (Fig. 4C and D; Table 5) but nevertheless showed more reduction in minus-strand RNA synthesis directed by t1 than did the nonspecific RNAs, L1 and the RCNMV 3′ sequence (Fig. 4A). RNA t34, in which the bulge in the stem of domain D2 was removed, was a moderate competitor with an IC50 of 62 nM (Table 5). Taken together, the results indicate that the highest-affinity RdRp binding element(s) in the TMV-L 3′-UTR lies within a region comprising domain D2 and the central core, C, but that domains D1 and D3 also bind to the RdRp with a lower affinity.

DISCUSSION

This study has defined several structural features in the TMV-L 3′-UTR which are needed for efficient promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro. One of these is the sequence of the unpaired 4 nucleotides at the 3′ terminus, which has also been found to be important for minus-strand synthesis by BMV (7, 42) and TYMV (11, 39), although removal or substitution of the 3′-terminal A had a much greater inhibitory effect on TMV templates than on those of the other two viruses. Maximal synthesis was obtained with the wild-type 3′-terminal CCCA sequence or with the mutant 3′-terminal GGCA sequence. Taken together with previous results indicating that TMV-L RNA synthesis initiates with a G (33), it is likely that the penultimate C acts as an initiation site, as found for minus-strand synthesis in vitro by RdRps of BMV (7, 38) and TYMV (39). The importance of the 3′-terminal sequence is indicated by the reduction of template efficiency to <1% that of the wild type by several mutations (Table 2), but some sequence flexibility is indicated, because transcriptional efficiencies of templates with 3′-terminal CACA, CUCA, CGCA, ACCA, UCCA, GUCA, and UGCA sequences were just over half that of the wild-type. It is clear, however, that a 3′-terminal NNCA sequence is not sufficient for an RNA to act as a template, since several RNAs with the wild-type CCCA end (t23, t25, t26, t31-t33, t39, t40, t42, t42 and t44 to t46) had template efficiencies of <1% that of the wild type (Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore, cucumber mosaic virus RNAs, which have 3′ ACCA termini, did not act detectably as templates for the TMV-L RdRp prepared by different methods in two different laboratories (33, 48). The four 3′-terminal nucleotides are also not the primary structure which determines binding of the template to the RdRp, since a 5′-terminal sequence linked to a 3′ CCCA terminus was a poor competitor in template-RdRp binding experiments (Fig. 4). Other structures in the TMV-L 3′-UTR which we have identified as important for minus-strand synthesis are a pseudoknot structure and, to a lesser extent, an upstream stem-loop structure in domain D1, the double-helical stem structure of domain D2 including a bulge in one strand, a double-helical region of the central core, C, and a stem-loop structure in domain D3. Of these regions, a structure comprising domain D2 and the central core, C, contains the highest-affinity RdRp-binding element. It is clear, therefore, that the promoter for TMV-L minus-strand RNA synthesis comprises elements of the TLS together with the upstream domain D3.

The results of the mutational analysis of domain D3 are in close agreement with the findings of similar studies on the role of domain D3 in TMV-L RNA replication in vivo (43). Removal of the region containing stems II to VI reduced TMV-L replication in protoplasts to 10% of that of the wild type (39) and minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro to 23% that of the wild type. Furthermore, removal of domain D3 reduced both TMV-L replication in protoplasts (43) and minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro to undetectable levels. This indicates that the reduction in TMV-L RNA synthesis of D3 mutants in vivo (43) is due primarily to a direct effect on RNA replication and is not only a secondary consequence of effects on translation of TMV-L RNA and synthesis of the 126- and 183-kDa replication proteins. The congruence of the in vivo and in vitro results also validates the use of an in vitro system to study TMV-L minus-strand RNA synthesis. The most thorough structural study of the TMV 3′-UTR (19) indicates that domains D1 and D3 behave independently. However, comparison of the structures containing either the central core, C, with domains D1 and D2 or the central core, C, with domains D1, D2, and D3 showed that domain D3 stabilized the 6-bp double-helical segment S4 of the central core, C (19), a segment essential for TMV-L minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro. Hence one function of domain D3 in minus-strand RNA synthesis may be indirect, via stabilization of the double-helical segment of core C. Domain D3 probably also makes direct contact with the RdRp, as shown by its low, but specific, affinity for the RdRp (t44 in Fig. 4C). However, domain D3 had no detectable template activity when attached to a 3′ CCCA initiating sequence, indicating that it is insufficient on its own to promote minus-strand synthesis.

Some of the regions in the TMV-L 3′-UTR identified as important for minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro have no obvious counterparts in the BMV 3′-TLS. For example, there are no regions in BMV RNA equivalent to the TMV domain D3, the central core region, C, or the stem-loop S3/L3 in domain D1. Other regions of the TMV and BMV TLSs may have similar functions in minus-strand RNA synthesis. We have shown that the pseudoknot in the TMV-L domain D1 is important for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis. Domain D1 probably makes contact with the RdRp, as shown by its low, but specific, affinity for the RdRp, but it is not the main element responsible for binding of the template to the RdRp, as shown by its comparatively low competitive ability in template-RdRp binding experiments (t31 in Fig. 4D). Disruption of a similarly placed, although structurally different, pseudoknot in the BMV TLS resulted in very low promoter activity in vitro (14) and greatly reduced BMV RNA synthesis in protoplasts (16), and the BMV pseudoknot also was not essential for binding of the template to the RdRp (6). The function of domain D1 in TMV-L replication may be to position the CA initiation site at the 3′ end of the template so that it is close to the catalytically active site of the RdRp, as suggested for the BMV 3′ pseudoknot structure (14).

A region comprising domain D2 and the central core, C, is essential for promotion of minus-strand RNA synthesis by the TMV-L RdRp in vitro and contains one or more high-affinity RdRp binding sites. It is possible that both the central core, C, and domain D2 bind to the RdRp, since RNAs in which either the S4 stem in the central core, C (t37) or the stem of domain D2 (t35) was disrupted were weak competitors of the wild type (t1) for binding to the RdRp. It is also possible that the S4 stem stabilizes the domain D2 structure and vice versa. Another function of the central core, C, is to determine the spatial orientation of domains D1, D2, and D3 (19), and hence it probably also plays a role (via the D1 domain) in positioning the 3′ end of the template close to the catalytically active site of the RdRp.

TMV domain D2 may be analogous to BMV domain C (18, 19). Both consist of stem-loops with a bulge in one strand of the stem, and both contain the putative anticodon loop. When stabilized by the addition of four GC base pairs to the head of BMV stem C, the resultant structure was able to bind to the BMV RdRp in the absence of the remaining part of the TLS (6). Although the bulge is clearly important in both the D2 stem and the BMV stem C for both template activity and RdRp binding, the effect of removing the bulge was more severe in the case of BMV. Bulge deletion mutants of TMV and BMV had template efficiencies of 24% (t34 in Table 4) and 6% (14) of those of the respective wild types, and in binding competition experiments they had IC50 of 62 nM (t34 in Table 5) and >75 nM (6), respectively.

The functional similarities between regions of the TLSs in BMV and TMV described above may account for the ability of chimeras, in which the 3′-UTR of TMV-L RNA had been replaced by the the 3′-UTR of BMV, to replicate to a limited extent (0.1 to 1% of that of TMV-L RNA) in tobacco protoplasts (24). Nevertheless, there are considerable differences between the TLSs of TMV and BMV (18, 19), and the 3′-most 172 nucleotides of TMV RNA do not direct RNA synthesis by the BMV RdRp in vivo (24) or in vitro (6) or compete significantly with the BMV TLS in binding to the BMV RdRp (6).

The results described here for the template requirements of the TMV-L RdRp for minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro are in contrast to the template requirements described for the TYMV RdRp. The 3′ end of TYMV RNA also mimics tRNAs, but with a structure different from that of either TMV or BMV (13, 20). Like TMV and BMV it has a 3′-pseudoknot structure, but disruption of this pseudoknot only reduced minus-strand synthesis in vitro by about 50% (10, 39). The main determinant of the TYMV 3′ tRNA-like region for minus-strand synthesis in vitro was the ACCA end (10, 39, 40). The minimal template was 9 nucleotides with an unpaired ACCA 3′ end, although increased template length with proper base stacking improved transcriptional efficiency (12). Furthermore, internal initiation at NPyCPu sites was demonstrated on a variety of templates (11, 12, 40). It has been suggested that the TYMV RdRp may not require a unique promoter and that the TLS may act as a repressor to prevent initiation at internal sites (13). Specific elements of the TLS are required for efficient replication in vivo (21, 41). Another suggestion is that the isolated TYMV RdRp may be a core enzyme which lacks additional viral or host proteins needed to confer specific promoter binding (12). This explanation is based on parallels between transcription by RdRps and DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (1, 27). As an example, the yeast DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II consists of a core comprised of 12 polypeptides, which assembles with general transcription factors to form a 35-subunit initiation complex at a promoter and start transcription. Positive and negative regulation of transcription is achieved with a 20-protein “Mediator” complex, and additional factors are required for elongation (25). Isolated polymerase preparations containing different subsets of these proteins exhibit various degrees of specificity for the template, ranging from lack of specificity for the core enzyme to high specificity and responsiveness to activators for the holoenzyme (32). With the TMV-L RdRp, we were unable to detect internal initiation at internal CA or CCA sequences in the 5′-UTR, or at a 3′-terminal CCCA sequence attached to the 5′-UTR, domain D1, domain D3, or domain D2 plus the central core, C. In fact, the minimal template which gave detectable minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro comprised the central core, C, linked to domains D1 and D2 and to the 3′ part of domain D3. Optimal synthesis required all three domains. The TMV-L RdRp has been shown to catalyze the complete replication of TMV RNA (33) and presumably therefore contains the viral and any host proteins required to recognize the whole promoter and confer template specificity. The TMV RdRp, however, differs from promoters for DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, such as the T7 promoter, in that it appears to recognize RNA secondary or tertiary structural elements rather than recognizing a specific sequence.

Recently Chandrika et al. (5) compared the replication of full-length and defective (d) TMV RNAs in protoplasts from tobacco suspension culture cells using mutants, and chimeras constructed between TMV and other tobamoviruses, in domains D3 and D1. The requirement of the domain D3 3′-TLS-proximal pseudoknot and the pseudoknot in domain D1 for efficient replication of both full-length RNAs and dRNAs in protoplasts is in agreement with the results reported here for minus-strand synthesis in vitro. However, differences were noted in the effects of some mutations on the replication of full-length and dRNAs. Removal of the middle pseudoknot in domain D3 reduced replication of the full-length RNA to 30% that of the respective wild-type RNA but had no effect on the replication of the dRNA. Mutations in the 3′-most 28 nucleotides, which include the domain D1 pseudoknot, generally had greater effects on the replication of the dRNAs than on that of the full-length RNAs. The specificity of chimeric RNAs was shown to lie in the 3′-most 28 nucleotides, although this sequence on its own was insufficient as a replication signal, since a dRNA mutant containing the 3′-most 28 nucleotides, but lacking the rest of the 3′-UTR, failed to replicate. This is consistent with the failure of t31, which contains only the 3′-terminal 40 nucleotides of TMV RNA, to act as a template for minus-strand synthesis by the RdRp in vitro. Replication of both full-length and dRNAs in vivo (5, 43), as well as minus-strand RNA synthesis from 3′ templates by the isolated RdRp in vitro, requires additionally the central core region and domain D2, identified here as the main RdRp binding region, as well as the 3′-proximal pseudoknot of domain D3.

There are several possible explanations for the differences observed in the effects of some 3′-UTR mutations or chimeric constructs on the replication of full-length and dRNAs. First, cis-preferential replication of full-length RNAs could involve interaction of nascent 126- and 183-kDa replication proteins with the 3′-UTR, whereas replication of dRNAs in trans could involve interaction of a preformed replication complex with the 3′-UTR. Secondly, full-length and dRNAs could be replicated by different RdRp complexes, containing different host components or different ratios of viral and host components. The protein composition of replication complexes of full-length RNAs has been studied (34, 48), but there is no information on the composition of the RdRp complexes that replicate dRNAs. A third explanation is suggested by the capability of the dRNAs studied to synthesize a truncated 126-kDa protein containing the methyltransferase (MT) domain (29, 30). It was previously suggested that the MT domain might target dRNAs for replication but could then be displaced by existing replication complexes (30). If so, the initial interaction between the MT domain and the 3′-UTR may have structural requirements different from those of interactions of the 126- and 183-kDa proteins with the 3′-UTR. It is clear that further work is needed to determine unequivocally if interactions between the TMV replicase and the 3′-UTR are different for cis-preferential replication and replication in trans. An in vitro system, such as the one reported here, involving interactions of the 3′-UTR with RdRp derived from replication complexes formed in vivo on full-length TMV RNA could help to distinguish these possibilities, as well as defining the structural requirements for RdRp interactions with satellite TMV RNA, which also has a 3′-TLS and upstream pseudoknotted domain (similar to TMV domain 3) (22).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by a grant from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins S, Stawicki S S, Faurote G, Siegel R, Kao C C. Mechanistic analysis of RNA synthesis by RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from two promoters reveals similarities to DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. RNA. 1998;4:455–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer J C, Haenni A -L. Infectious transcripts and cDNA clones of RNA viruses. Virology. 1994;198:415–426. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buck K W. Comparison of the replication of positive-stranded RNA viruses of plants and animals. Adv Virus Res. 1996;47:159–251. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60736-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck K W. Replication of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1999;354:613–627. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrika R, Rabindran S, Lewandowski D J, Manjunath K L, Dawson W O. Full-length tobacco mosaic virus RNAs and defective RNAs have different 3′ replication signals. Virology. 2000;273:198–209. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman M R, Kao C C. A minimal promoter for minus-strand RNA synthesis by the brome mosaic virus polymerase complex. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:709–720. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman M R, Rao A L N, Kao C C. Sequences 5′ of the conserved tRNA-like promoter modulate the initiation of minus-strand synthesis by the brome mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virology. 1998;252:458–467. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson W O, Lehto K M. Regulation of tobamovirus gene expression. Adv Virus Res. 1992;38:307–342. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson W O, Beck D L, Knorr D A, Grantham G L. cDNA cloning of the complete genome of tobacco mosaic virus and production of infectious transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1832–1836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deiman B A L M, Kortlever R M, Pleij C W A. The role of the pseudoknot at the 3′ end of turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA in minus-strand synthesis by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Virol. 1997;71:5990–5996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5990-5996.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deiman B A L M, Koenen A K, Verlaan P W G, Pleij C W A. Minimal template requirements for initiation of minus-strand synthesis in vitro by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of turnip yellow mosaic virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3965–3972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3965-3972.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deiman B A L M, Koenen A K, Pleij C W A. In vitro transcription by the turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA polymerase: a comparison with the alfalfa mosaic virus and brome mosaic virus replicases. J Virol. 2000;74:264–271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.264-271.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreher T W. Functions of the 3′-untranslated regions of positive strand RNA viral genomes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1999;37:151–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dreher T W, Hall T C. Mutational analysis of the sequence and structural requirements in brome mosaic virus RNA for minus strand promoter activity. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreher T W, Bujarski J J, Hall T C. Mutant viral RNAs synthesized in vitro show altered aminoacylation and replicase activities. Nature. 1984;311:171–175. doi: 10.1038/311171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreher T W, Rao A L, Hall T C. Replication in vivo of mutant brome mosaic virus RNAs defective in aminoacylation. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:425–438. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duggal R, Lahser F, Hall T C. Cis-acting sequences in the replication of plant viruses with plus-sense genomes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:287–309. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felden B, Florentz C, Giegé R, Westhof E. Solution structure of the 3′-end of brome mosaic virus genomic RNAs: conformational mimicry with canonical tRNAs. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:508–531. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felden B, Florentz C, Giegé R, Westhof E. A central pseudoknotted three-way junction imposes tRNA-like mimicry and the orientation of three 5′ upstream pseudoknots in the 3′ terminus of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. RNA. 1996;2:201–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florentz C, Giegé R. tRNA-like structures in plant viral RNAs. In: Söll D, RajBhandary U, editors. tRNA: structure, biosythesis, and function. Washington, D. C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin J B, Skuzeski J M, Dreher T W. Characterization of chimeric turnip yellow mosaic virus genomes that are infectious in the absence of aminoacylation. Virology. 1997;230:113–124. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gultyaev A P, van Batenburg E, Pleij C W A. Similarities between the secondary structure of satellite tobacco mosaic virus and tobamovirus RNAs. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2851–2856. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes R J, Buck K W. Analysis of replication complexes of positive strand RNA plant viruses. In: Davison A J, Elliott R M, editors. Molecular virology: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1993. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa M, Kroner P, Ahlquist P, Meshi T. Biological activities of hybrid RNAs generated by the 3′-end exchanges between tobacco mosaic and brome mosaic viruses. J Virol. 1991;65:3451–3459. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3451-3459.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornberg R D. Eukaryotic transcriptional control. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:M46–M49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai M M C. Cellular factors in the transcription and replication of viral genomes: a parallel to DNA-dependent RNA transcription. Virology. 1998;244:1–12. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leathers V, Tanguay R, Kobayashi M, Gallie D R. A phylogenetically conserved sequence within viral 3′ untranslated RNA pseudoknots regulates translation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5331–5347. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewandowski D J, Dawson W O. Deletion of internal sequences results in tobacco mosaic virus defective RNAs that accumulate to high levels without interfering with replication of the helper virus. Virology. 1998;251:427–437. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewandowski D J, Dawson W O. Functions of the 126- and 183-kDa proteins of tobacco mosaic virus. Virology. 2000;271:90–98. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathews D H, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner D H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure, J. Mol Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myer V E, Young R A. RNA polymerase II holoenzymes and subcomplexes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27757–27760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osman T A M, Buck K W. Complete replication in vitro of tobacco mosaic virus RNA by a template-dependent, membrane-bound RNA polymerase. J Virol. 1996;70:6227–6234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6227-6234.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osman T A M, Buck K W. The tobacco mosaic virus RNA polymerase complex contains a plant protein related to the RNA-binding subunit of yeast eIF-3. J Virol. 1997;71:6075–6082. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6075-6082.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plante C A, Kim K -H, Pillai-Nair N, Osman T A M, Buck K W, Hemenway C L. Soluble, template-dependent extracts from Nicotiana benthamiana plants infected with potato virus X transcribe both plus- and minus-strand RNA templates. Virology. 2000;275:444–451. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao A L, Hall T C. Interference in trans with brome mosaic virus replication by RNA-2 bearing aminoacylation-deficient mutants. Virology. 1991;180:16–22. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90004-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel R W, Adkins S, Kao C C. Sequence-specific recognition of a subgenomic promoter by a viral RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11238–11243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel R W, Bellon L, Beigelman L, Kao C C. Moieties in an RNA promoter specifically recognized by a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh R N, Dreher T W. Turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: initiation of minus strand synthesis in vitro. Virology. 1997;233:430–439. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh R N, Dreher T W. Specific site selection in RNA resulting from a combination of nonspecific secondary structure and -CCRRR- boxes: initiation of minus strand synthesis by turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. RNA. 1998;4:1083–1095. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skuzeski J M, Bozarth C S, Dreher T W. The turnip yellow mosaic virus tRNA-like structure cannot be replaced by generic tRNA-like elements or by heterologous 3′ untranslated regions known to enhance mRNA expression and stability. J Virol. 1996;70:2107–2115. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2107-2115.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun J H, Adkins S, Faurote G, Kao C C. Initiation of (−)-strand synthesis catalyzed by the BMV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: synthesis of oligonucleotides. Virology. 1996;226:1–12. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takamatsu N, Watanabe Y, Meshi T, Okada Y. Mutational analysis of the pseudoknot region in the 3′ noncoding region of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:3686–3693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3686-3693.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takamatsu N, Watanabe Y, Iwasaki T, Shiba T, Meshi T, Okada Y. Deletion analysis of the 5′ untranslated leader sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. J Virol. 1991;65:1619–1622. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1619-1622.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanguay R L, Gallie D R. Isolation and characterization of the 102-kilodalton RNA-binding protein that binds to the 5′ and 3′ translational enhancers of tobacco mosaic virus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14316–14322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai C H, Dreher T W. Turnip yellow mosaic virus RNAs with anticodon loop substitutions that result in decreased valylation fail to replicate efficiently. J Virol. 1991;65:3060–3067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3060-3067.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Belkum A, Abrahams J P, Pleij C W A, Bosch L. Five pseudoknots at the 204 nucleotides long 3′ noncoding region of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:7673–7686. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.21.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe T, Honda A, Iwata A, Ueda S, Hibi T, Ishihama A. Isolation from tobacco mosaic virus-infected tobacco of a solubilized template-specific RNA-dependent RNA polymerase containing a 126K/183K protein heterodimer. J Virol. 1999;73:2633–2640. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2633-2640.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuker M, Mathews D H, Turner D H. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: a practical guide. In: Barciszewski J, Clark B F C, editors. RNA biochemistry and biotechnology. NATO ASI Series. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]