Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae, a member of the autochthonous human gut microbiota, utilizes a variety of virulence factors for survival and pathogenesis. Consequently, it is responsible for several human infections, including urinary tract infections, respiratory tract infections, liver abscess, meningitis, bloodstream infections, and medical device-associated infections. The main studied virulence factors in K. pneumoniae are capsule-associated, fimbriae, siderophores, Klebsiella ferric iron uptake, and the ability to metabolize allantoin. They are crucial for virulence and were associated with specific infections in the mice infection model. Notably, these factors are also prevalent in strains from the same infections in humans. However, the type and quantity of virulence factors may vary between strains, which defines the degree of pathogenicity. In this review, we summarize the main virulence factors investigated in K. pneumoniae from different human infections. We also cover the specific identification genes and their prevalence in K. pneumoniae, especially in hypervirulent strains.

Keywords: Virulence factors, Hypervirulence, Virulence genes, Klebsiella pneumoniae

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae, a member of the Enterobacterales order and Enterobacteriaceae family [1], is a rod-shaped, gram-negative, and member of the autochthonous human gut microbiota also found in other environmental niches [2]. Although the literature addresses K. pneumoniae as an opportunistic bacterium [3–5], in this case, referring to the classical strains, there are hypervirulent strains capable of causing disease in previously healthy people [6–8].

The presence and type of virulence factor may vary between strains, and this characteristic defines the degree of pathogenicity [9]. Classical (or opportunistic) K. pneumoniae comprises most strains isolated from infections in immunocompromised patients, usually acquired after hospitalization [9, 10]. The main infections caused by classical K. pneumoniae are respiratory tract infection (RTI), bloodstream infection (BSI), and urinary tract infection (UTI) [11]. Classical strains are of low virulence and frequently exhibit high rates of antibiotic resistance [12, 13]; consequently, these infections are often difficult to treat.

Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae is highly invasive and is commonly found in community-acquired infections [14–18], mainly liver abscesses, meningitis, and disseminated infections [11, 19, 20]. Although more common in the community, several studies have reported that these strains cause hospital outbreaks [21, 22]. In contrast to classical strains, hypervirulent isolates are usually sensitive to antibiotics [6, 12, 13]; however, the convergence of multidrug resistance and hypervirulence is emerging [23–25], which is a global concern. This review aims to focus on the prevalence of virulence factors in K. pneumoniae and point out which characterizes hypervirulent strains.

Virulence Factors in Klebsiella pneumoniae

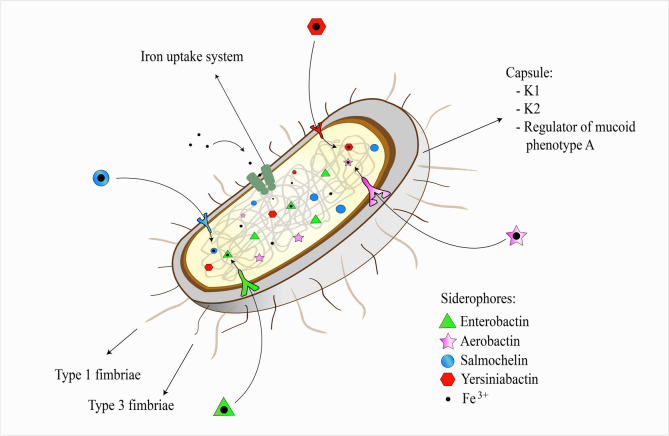

The main studied virulence factors in K. pneumoniae are capsule-associated, fimbriae, siderophores, Klebsiella ferric iron uptake, and the ability to metabolize allantoin (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the main virulence factors of Klebsiella pneumoniae

The target genes used to search for virulence factors in Klebsiella pneumoniae from different human infections are following: capsule-associated factors—magA for serotype K1, k2A for serotype K2, and rmpA/rmpA2 for the regulator of mucoid phenotype A; fimbriae—fimH for type 1 fimbriae and mrkD for type 3 fimbriae; siderophores—entB for enterobactin, iucA, iucB, iucC, and iucD for aerobactin, iroB, and iroN for salmochelin, and ybtA, ybtS, irp1, irp2, and fyuA for yersiniabactin; Klebsiella ferric iron uptake—kfu; allantoin-utilizing capability—allS (virulence factor not shown in the figure).

Capsule

The capsule consists of an extracellular polysaccharide matrix surrounding the bacteria and is the most relevant and studied virulence factor in K. pneumoniae. The role of the capsule in K. pneumoniae is to prevent phagocytosis, hinder the antibacterial activity of antimicrobial peptides, block complement components preventing complement-mediated lysis and opsonization, and prevent fulminant activation of the immune response [9]. Although the capsule has historically been a target for vaccines in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, no licensed vaccine or therapy targeting the K. pneumoniae capsule is currently available to prevent or treat infections. However, studies show that the K. pneumoniae capsule has significant potential as a vaccine target [26–29].

Capsule biosynthesis involves a set of genes in the capsule synthesis locus, whose central region is highly variable and responsible for the variety of capsular serotypes [30, 31]. Seventy-seven capsular serotypes (referred to as K-types) were identified in K. pneumoniae by phenotypic studies; however, many other serologically non-typeable strains are now typed based on genomic analyses of the capsule synthesis loci (K-loci), with at least 134 distinct K-loci identified (referred to as KL-type) [31]. Nevertheless, K1 and K2 are the most common serotypes in hypervirulent strains [15, 32–34]. The magA gene is a specific marker of the K1 capsular serotype [35, 36]. K. pneumoniae strains with this serotype are strongly associated with liver abscesses [32, 37–39]. This association was confirmed in vivo mouse experiments, where the K. pneumoniae serotype K1 magA-deficient mutant lost the ability to cause liver abscess compared to the wild-type K1 strain [40]. The specific allele of serotype K2 is referred to as k2A. Similar to K1 serotypes, K. pneumoniae K2-deficient lost the ability to cause a liver abscess in vivo mouse experiments compared to wild-type K2 strains [40].

Tan et al. [37] found an association among pyogenic liver abscess, K. pneumoniae serotype K1, and a positive string test in Singapore. The string test is a phenotypic test that determines the hypermucoviscosity phenotype [41] and was widely used as a hypervirulence marker. However, the molecular detection of the genes prmpA/prmpA2 (regulator of mucoid phenotype A/A2), iroB (salmochelin siderophore), and iucA (aerobactin siderophore) by conventional PCR is currently the best diagnostic method to identify hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strains, with diagnostic accuracy of > 95% for each gene [42]. In comparison, the detection accuracy of hypervirulent strains using the string test was 90% in the mentioned study.

The prevalence of liver abscess caused by K. pneumoniae serotype K1 was 64.3% (45/70) in an ethnically diverse population (Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Caucasian) [43] and 39.2% (20/51) in a study in China [39]. K. pneumoniae serotype K2 is the second most commonly found in liver abscess [32, 39, 43, 44]. The prevalence of K2 strains in pyogenic liver abscesses in a population of mainland China was 31.4% (16/51) [39], and in another study involving Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Caucasian people, it was 20% (14/70) [43]. In both studies, K1 was the dominant serotype.

K. pneumoniae serotype K1 is also common in bacteremias, and in many cases, pneumonia and liver abscesses are the primary sources [32, 37, 45]. The prevalence of magA in bacteremia isolates in a Japanese study was 47.3% (61/129) [46]. In two Chinese studies, the prevalence of K1 in BSI was 11% (38/344) [47] and 4.7% (9/190) [48]. In the last-mentioned study, serotype K2 was the most prevalent, 11.58% (22/190). Lastly, the prevalence of the K1 serotype was 13.3% (30/225) in bacteremia cases in Taiwan [49]. Although the prevalence appears low, K1 was the most prevalent serotype in almost all studies, followed by serotype K2, even with 134 known KL-types.

The prevalence of serotype K1 was 15.2% (5/33) in meningitis isolates in a retrospective study in different regions of Taiwan [50]. K2 strains were more prevalent than K1 in the same study, reaching 33.3% (11/33) of cases [50]. However, it is noteworthy that studies aimed at determining K. pneumoniae serotypes from meningitis are rare, making this actual prevalence a gap for future studies.

Regulator of mucoid phenotype A

The rmpA gene (regulator of mucoid phenotype A) regulates capsular synthesis, increases capsule production, and causes the hypermucoviscous phenotype [51]. This gene is a critical marker of hypervirulence in K. pneumoniae [34, 42], with a detection accuracy of > 95% [42].

Several studies report a high prevalence of the rmpA gene in K. pneumoniae isolated from a liver abscess [37, 44, 52]. All isolates from a liver abscess from a Taiwanese population had the rmpA gene regardless of serotype [32]. In the study by Lin et al. [44] in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, 100% of K2 strains from liver abscesses presented the rmpA gene. In isolates from meningitis cases in a Taiwanese population, the prevalence of the rmpA gene was 69.7% (23/33), and that of rmpA2 was 60.6% (20/33) [50].

Although the distribution of capsular serotypes in community-acquired UTI by K. pneumoniae is not defined, the prevalence of rmpA was 29.6% in strains with the hypermucoviscous phenotype in a retrospective study in Taiwan [53]. On the other hand, the prevalence of the rmpA gene in UTI cases was 2.3% (4/170) in an Indian study [54]. In Portugal, the magA and rmpA genes were not found in the 81 UTI isolates in the study (50 community-acquired and 31 hospital-acquired isolates) [55]. The low occurrence of this virulence factor with UTI isolates is expected, as it is a marker of hypervirulence [42].

In community-acquired pneumonia, the prevalence of the rmpA gene was 69% (20/29) in sputum isolates in Taiwan [53]. The authors found an association of the rmpA gene with pneumonia compared to fecal isolates from healthy adults, where the prevalence was approximately 11.8% (9/76) (CI 95% 5.9–42.2; p < 0.0001). In a study of older adults in China with lower RTI caused by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, rmpA was present in 74.19% (23/31) of the isolates [56]. On the other hand, another study in India reported the prevalence of rmpA in 18.4% (7/38) of RTI [54]. In a study involving people from six countries (Australia, Indonesia, Laos, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States), rmpA/rmpA2 were significantly associated with invasive infection (rmpA: odds ratio 15; p < 0.0001; rmpA2: odds ratio 9.1; p < 0.0001) [57].

The prevalence of rmpA in K. pneumoniae from blood cultures ranges from 6.6 to 37.3% in studies in Asian countries: 37.3% (84/225) in Taiwan [49], 26.8% (51/190) and 23% (79/344) in China [47, 48], 13.2% (17/129) in Japan [46], and 6.6% (2/30) in India [54]. The design of the studies may have been the reason for the wide range in prevalence. Additionally, the literature does not present data on the prevalence of this gene in K. pneumoniae isolated from this site in other countries outside the Asian continent, which makes an association of this virulence factor difficult with bacteremia cases.

Fimbriae

K. pneumoniae is believed to have ten types of fimbriae based on gene clusters identified in its genome. Recently, seven possible fimbrial gene clusters were identified and named kpa to kpg [58]; however, these clusters are still poorly characterized. The ecpABCDE operon responsible for expressing Escherichia coli common pilus (ECP), a highly studied fimbriae in E. coli, was recently found in the genome of K. pneumoniae [59]. However, little is said about it in the literature. On the other hand, type 1 and 3 fimbriae are the main adhesins in K. pneumoniae and are well characterized [60, 61].

Type 1 and 3 fimbriae are membrane-bound and are divided into structural and adhesive subunits. Each subunit has a specific gene organized in the fim (fimABCDEFGHIK-type 1 fimbriae) and mrk (mrkABCDF-type 3 fimbriae) gene clusters [60, 62]. However, of clinical and epidemiological interest, the adhesive subunits in the extremities are the most relevant in determining virulence [63, 64]. The genes responsible for these subunits are the most investigated in prevalence studies involving these virulence factors [55, 65–68].

Type 1 Fimbriae

In type 1 fimbriae, the fimH gene expresses the FimH adhesive subunit [69]. Through the FimH adhesin, K. pneumoniae recognizes and adheres to mannosylated residues in urothelium glycoproteins, uroplaquin Ia [70–72]. The urothelium is a tissue rich in uroplaquin [73]; for this reason, K. pneumoniae that expresses the fimH gene is considered uropathogenic and is frequently found in UTI [55, 65, 67, 68].

All K. pneumoniae isolates from UTI in the study by Eghbalpoor et al. [68] (n = 140) in Iran presented the fimH gene. The same occurred in cases of UTI in Algeria (n = 26) [67] and Portugal (n = 76) [65]. A study with type 1 fimbriae mutants showed that this adhesin is an essential virulence factor in UTI compared to the wild-type strain [74]. In this study, fim-deficient mutants had impaired urovirulence, and complementation of the fim gene cluster via plasmids restored this characteristic. Notably, almost all K. pneumoniae have FimH, which contributes to the infection of different sites along with other coexisting virulence factors. In a study, for example, the fimH gene was found in 100% of bloodstream isolates (n = 11), pus (n = 11), lung (n = 4), cerebrospinal fluid (n = 1), and peritoneal fluid (n = 1) [67].

Type 3 Fimbriae

The mrkD gene expresses the type 3 fimbriae adhesive subunit [64]. Although the mrkD gene has been reported in uncomplicated cases of UTI by K. pneumoniae strains [55, 65, 68], type 3 fimbriae do not make a significant contribution to this infection, which has already been demonstrated in a study with deficient mutants [74]. FimH adhesin, usually present with MrkD in isolates, is primarily responsible for urovirulence [74].

Several studies have demonstrated the ability of K. pneumoniae to form biofilms [66–68, 75–77]. K. pneumoniae type 3 fimbriae mediate biofilm formation, which has already been demonstrated by comparing mrk-deficient mutants and the wild-type strain [74, 76]. The prevalence of the mrkD gene in biofilm-producing K. pneumoniae was 100% (n = 43) in a study in China [77]. This same study found the fimH gene in 88.4% (38/43) of the isolates; therefore, the MrkD adhesin does not depend on FimH to form a biofilm. In Portugal, Bandeira et al. [66] also found biofilm-producing K. pneumoniae negative for fimH. However, in K. pneumoniae containing type 1 and 3 fimbriae, adhesins may contribute to UTI initiation (colonization process) and persistence [78].

Due to the ability to adhere to biotic and abiotic surfaces, such as glass, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and silicone tubes [78, 79], K. pneumoniae is commonly found in medical devices such as urinary and intravascular catheters and endotracheal tubes [79, 80]. Therefore, K. pneumoniae is frequently reported in infections associated with these devices [80–82]. For example, a study in Algeria showed that 91.7% of K. pneumoniae isolates from urinary catheters and endotracheal tubes had the mrkD gene. Importantly, patients who were using these devices had severe infections [79]. Biofilm formation confers a protective barrier against the host immune system and is a physical barrier against antibiotics [66, 83]. In a biofilm, antibiotic resistance tends to be 10 to 1000 times higher than in the planktonic form [66, 79, 84].

Siderophores

Iron is an essential nutrient for both humans and microorganisms. For this reason, the concentrations of free iron in the human body are small because they are stored in proteins such as hemoglobin, haptoglobin, ferritin, and transferrin [85]. This concentration can be more intensely decreased with the help of other proteins (e.g., lactoferrin and hepcidin) in response to infection to inhibit bacterial growth [85]. Conversely, K. pneumoniae has mechanisms that capture and compete for this low free iron in the host. Siderophores are proteins with a high affinity for iron secreted to chelate and deliver iron to bacteria, essential for their growth and metabolism [86]. The ability to capture iron is higher in these proteins than in the host [9]; therefore, this is a relevant virulence factor.

Enterobactin

Among the siderophores that K. pneumoniae can secrete, enterobactin, encoded by the entABCDEF gene cluster where the entB gene was a marker in several studies [15, 54, 87, 88], is widespread in classical and hypervirulent strains [89]. Nonetheless, this siderophore is irrelevant in virulence because, when released, it is completely inhibited by the host’s innate immune protein lipocalin-2 [89]. Therefore, enterobactin is not associated with specific clinical manifestations.

Although enterobactin is ubiquitous in K. pneumoniae, the coexistence of different siderophores is common in hypervirulent strains. Studies show that hypervirulent K. pneumoniae quantitatively produce more siderophores than classical strains [90, 91]. Yersiniabactin, aerobactin, and salmochelin are siderophores associated with high virulence, and unlike enterobactin, these siderophores are not inhibited by lipocalin-2 [92, 93]. Peculiarly, enterobactin is the siderophore with the greatest iron affinity [90, 94].

Yersiniabactin

Yersiniabactin is the second most common siderophore in K. pneumoniae. The prevalence of yersiniabactin is approximately half of the classical strains but in almost all hypervirulent isolates [57, 95]. The gene cluster responsible for the expression of this siderophore is formed by ybtAEPQSTUX (also called ybt), irp1, and irp2, responsible for synthesis, and fyuA, whose product is the receptor [96, 97]. Among these genes, ybtA [98, 99], ybtS [54, 100], irp1 [88, 101], irp2 [102, 103], and fyuA [104, 105] were used as markers in several studies.

As is common in classic and hypervirulent K. pneumoniae, yersiniabactin is present in strains that cause different infections, coexisting with other virulence factors. However, in a study involving six countries (Australia, Indonesia, Laos, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States), yersiniabactin was a strong predictor of invasive infection (OR 7.4; IC: 95% 2.2–40; p = 0.0001) [57].

In a study conducted in China, Bachman et al. [89] observed that yersiniabactin is a relevant virulence factor during pulmonary infection through evasion of lipocalin-2. Additionally, these authors described that yersiniabactin was significantly more prevalent in RTI isolates than in other sites, such as blood and urine. The prevalence of this virulence factor in K. pneumoniae isolated from RTI in an Indian study was 60.5% (23/38), the most prevalent siderophore after enterobactin [54]. In the study by Yan et al. [95] in China, the prevalence of the ybtS gene in classical and hypervirulent isolates from ventilator-associated pneumonia was 83.6%. In the mentioned study, 88.6% (31/35) of the classical isolates and 71.6% (10/14) of the hypervirulent isolates had yersiniabactin, and this difference in prevalence was not statistically significant (CI 95% 0.8–12.0; p = 0.202).

The prevalence of ybtS in K. pneumoniae from blood cultures in an Indian study was 63.3% (19/30) [54]. In two studies conducted in China, ybtS was present in 55.8% (192/344 and 106/190) of K. pneumoniae isolated from BSI [47, 48]. The prevalence of this virulence factor was 29.5% (38/129) in bacteremia isolates in Japan [46]. These findings suggest a possible correlation between ybtS and this infection, but this should be analyzed with caution, given the lack of similar studies in countries outside Asia.

Aerobactin

Aerobactin is a critical virulence factor often found in hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strains but rare in classical strains [34, 42, 90, 95, 106, 107]. For this reason, it is a critical marker in identifying hypervirulent K. pneumoniae [42, 106], with an accuracy of 96% [42]. The iucABCD gene cluster is responsible for this siderophore [108], and the iutA gene encodes the outer membrane receptor for aerobactin. The iutA gene is frequently used as a marker for this siderophore in K. pneumoniae [65, 87, 109]. iucA [110, 111], iucB [88], iucC [55, 101], and iucD [112] are also markers. However, several studies do not specify the gene used as a target in detecting aerobactin [34, 37, 39].

Aerobactin has been reported in K. pneumoniae isolated from different infections. The prevalence of aerobactin from blood cultures ranges from 6.6% to 50.9% in studies conducted in Asian countries. A study in China reported a prevalence of 50.9% (175/344) of the iucA gene in K. pneumoniae from BSI [47]. Namikawa et al. [46] found the iutA gene in 12.4% (16/129) of bacteremia isolates in Japan. In an Indian study, aerobactin was prevalent in only 6.6% (2/30) of the isolates from blood cultures [54]. Regarding the presence of aerobactin in hypervirulent isolates, 100% (14/14) of K. pneumoniae with a hypermucoviscous phenotype arising from bacteremia presented this siderophore in a study in Korea [34]. The rmpA gene was also present in 100% of the cases of these isolates, which explains the hypermucoviscosity. On the other hand, the prevalence of aerobactin in non-hypermucoviscous strains was 10.5% (2/19) in mentioned study. In Singapore, aerobactin was the most found virulence factor among those related to hypervirulence in bacteremic episodes (48.8%, 63/129) [37]. Together with rmpA and the positive string test, aerobactin was significantly associated with primary liver abscess. Aerobactin was the most prevalent virulence factor (86.3%, 44/51) in K. pneumoniae isolated from liver abscesses among the virulence factors investigated in the study by Luo et al. [39] in a Chinese population. The liver is an iron-rich organ, as is the blood [113]. Therefore, this characteristic is believed to explain the high prevalence of aerobactin in K. pneumoniae isolated from these sites.

The prevalence of aerobactin in K. pneumoniae from community-acquired (20%, 10/50) and hospital-acquired UTI cases (16.1%, 5/31) appears to be low [55]. Of 170 UTI isolates from a study in India, only 1.76% (3/170) had aerobactin [54]. In another study in Korea, the prevalence of aerobactin was only high in hypermucoviscous strains, with aerobactin being the most prevalent virulence factor (80%, 8/10). On the other hand, the prevalence in non-hypermucoviscous isolates was 15.5% (11/71). In this case, there was an association between the presence of aerobactin and the hypermucoviscous phenotype (CI 95% 4.0–106.3; p < 0.0001) [114]. In meningitis cases of a retrospective study performed in different regions of Taiwan, the prevalence of aerobactin in K. pneumoniae was 66.7% (22/33), and this siderophore was associated with primary meningitis compared to post-craniotomy meningitis (90%, 18/20 vs. 30.8%, 4/13, respectively; CI 95% 3.3–106.7; p = 0.0007) [50].

Salmochelin

Like aerobactin, the prevalence of salmochelin is high in hypervirulent K. pneumoniae and rare in classical strains [42, 95, 115, 116]. For this reason, it was an excellent marker of hypervirulence in one study, with 97% accuracy [42]. Salmochelin and its receptor are encoded by the iroA gene cluster, composed of the iroBCDE-iroN genes [117, 118]. iroB [88, 93, 95] and iroN [15, 119] are the most used target genes investigating this siderophore.

Salmochelin was statistically associated with invasive infection [57]. In a mouse model of sepsis, the iroA gene cluster was correlated with increased virulence and infection [92]. This siderophore is common in K. pneumoniae associated with liver abscess and appears to correlate with RTI. In E. coli, salmochelin promoted lung infection in an avian air sac model [120]. In K. pneumoniae, it was associated with worsening pulmonary infection compared to an enterobactin-producing strain alone in a murine pneumonia model [121]. However, the role of salmochelin in pulmonary infection remains unclear, and further studies are needed to fill this knowledge gap.

The prevalence of iroB in hypervirulent K. pneumoniae from ventilator-associated pneumonia was 100% (14/14) in a study in China [95]. This siderophore was absent in classical strains (n = 35) in the same study. Although we know of the association between yersiniabactin and ventilator-associated pneumonia and that ybtS was the most prevalent in that same study, it must be agreed that the coexistence of salmochelin potentiated the virulence of K. pneumoniae isolates. Despite the possible correlation with RTI, further studies on the prevalence of salmochelin in cases of K. pneumoniae pneumonia should be carried out.

Of 61 cases of liver abscess due to bacterial causes acquired in the community in a study conducted in China, 53 were due to K. pneumoniae. Of these, 88.7% (47/53) of the isolates were hypervirulent, and the prevalence of the iroB and iucA (aerobactin) genes was 100% (n = 47) [122]. In another study in China, the prevalence of salmochelin in isolates from pyogenic liver abscesses was 24.5% (40/163), and the most significant number of cases was associated with non-K1/K2 serotypes (p < 0.001) [119]. On the other hand, all isolates of K1 (n = 45) and K2 (n = 14) serotypes from liver abscesses in an ethnically diverse population presented salmochelin, and this high prevalence was associated with K1 serotype compared with non-K1 serotypes (100% vs. 84%; p = 0.014, for K1 and non-K1, respectively). The authors found salmochelin in 94.3% (66/70) of the isolates, the most prevalent siderophore [43].

Iron Uptake System

Host iron uptake can also be done by the Kfu system (Klebsiella Ferric Uptake), an ABC transporter that is encoded by the kfuABC operon [123]. The contribution of this factor to the increase in virulence involves the acquisition and metabolism of iron from the host, which ensures bacterial growth. Deleting this system (ΔkfuABC) reduced the virulence of K. pneumoniae in the mice model study, and its presence was associated with invasive infection [123]. There is a strong correlation between the kfu gene and hypervirulence in K. pneumoniae. Perhaps this is due to the high prevalence of this cluster in K. pneumoniae serotype K1 compared to non-K1 serotypes [33, 34, 39, 43, 100, 124].

The kfu gene is common in K. pneumoniae isolated from liver abscesses [37, 43, 100]. In a study in China, 100% (20/20) of K1 strains from liver abscesses had kfu, while only 6.25% (1/16) of K2 strains and 33.3% (5/15) of other serotypes had this virulence factor [39]. The prevalence of kfu in liver abscess isolates from a Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Caucasian population was also 100% (45/45) in K1 strains [43].

A study in Iraq found kfu in 54% (7/13) of K. pneumoniae isolated from UTIs [125]. The prevalence of kfu in isolates of a study in Portugal was 52.6% (10/19) in hospital-acquired UTI isolates and 42.1% (24/57) in community-acquired UTI isolates [65]. In India, this virulence factor was found in 19.4% (33/170) of K. pneumoniae isolates in urine samples [54]. In a Brazilian study, the prevalence of kfu in K. pneumoniae from UTIs was 14.6% (7/48) [126]. Although there are no studies with kfu-deficient mutants in K. pneumoniae from UTI, it is noted that this virulence factor is common in isolates from this site. However, there is variability in its prevalence in different countries.

The prevalence of kfu in K. pneumoniae identified in blood cultures was 43.3% (13/30) in an Indian study [54]. In a Japanese study, the prevalence of kfu in isolates from bacteremia was 30.2% (39/129) [46]. Another study in the same country found a similar prevalence, 29.9% (26/87) [124]. In respiratory secretion isolates from an Indian population, kfu was found in 31.5% (12/38) of the isolates [54]. In patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia in China, kfu was only associated with hypervirulent strains in 50% of cases (7/14) compared to classical K. pneumoniae (2.9%, 1/35) (CI 95% 4.1–389.6; p = 0.0003) [95]. In addition to these findings, Ku et al. [50] reported this virulence factor in 30.3% (10/33) of the isolates from meningitis in Taiwan. The lack of other studies is a limiting factor that does not allow us to correlate these findings.

Allantoin Metabolism

Allantoin, a product of purine catabolism, can be degraded by K. pneumoniae as a nitrogen and carbon source. Several enzymes are involved in this metabolic pathway, expressed by three operons and two transcriptional regulators, AllR (repressor) and AllS (activator) [127]. The allS gene is essential in activating this system, and for this reason, it is used as a marker for this virulence factor [15, 37, 54, 98].

Deleting the allS gene in K. pneumoniae significantly decreased the virulence and capacity to cause liver abscess in vivo in mice [127]. Despite this association, the prevalence of allS in liver abscesses varies between studies. allS was prevalent in 65.7% (46/70) of K. pneumoniae isolates from liver abscesses in a Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Caucasian population [43] and 41.7% (21/51) in a study in China [39]. One hundred percent (7/7) of the isolates in another study in France had the allS gene, and all were serotype K1 belonging to ST23 [128].

The allS gene has a low prevalence in K. pneumoniae from UTI in different populations: 4.2% (2/48) in a study in Brazil [126], 2.6% (2/76) in a study in Portugal [65], and 0.58% (1/170) in UTI isolates in an Indian study [54]. In Korea, Kim et al. [114] found an association between the allS gene and the hypermucoviscous phenotype in K. pneumoniae from UTI (40%, 4/10 vs. 9.9%, 7/71; CI 95% 1.6–25.7; p = 0.026). The authors also found a higher frequency of allS in K. pneumoniae from bacteremia secondary to UTI than strains from patients without bacteremia (54.5%, 6/11 vs. 7.1%, 5/70; CI 95% 3.8–58.9; p = 0.0005). However, the prevalence of this virulence factor in UTI isolates is correlated with only hypermucoviscous strains. For example, the global prevalence of this gene in the Kim et al. [114] study was 13.6% (11/81).

The allS gene was not found in K. pneumoniae (n = 30) from blood cultures in India [54]. In Japan, allS was found in only 4.6% (6/129) of bacteremia isolates [46]. In another study in the same country, the prevalence of allS in K. pneumoniae from BSI was 24.1% (21/87) [124]. This virulence factor was found in 55.8% (192/344) [47] and 47.4% (90/190) [48] of bacteremia isolates in two studies in China. Unfortunately, we did not find similar studies in countries outside Asia.

Concluding Remarks

The most investigated virulence factors in K. pneumoniae from different types of infections were capsule-associated (serotypes K1, K2, and regulator of mucoid phenotype A), fimbriae (type 1 and type 3), siderophores (yersiniabactin, salmochelin, and aerobactin), Klebsiella ferric iron uptake, and the ability to metabolize allantoin. It has already been shown that the regulator of mucoid phenotype A (rmpA and rmpA2 plasmidial genes), salmochelin (iroB), and aerobactin (iucA) had > 95% diagnostic accuracy for identifying K. pneumoniae hypervirulent strains, whereas yersiniabactin (irp2) and serotypes K1 and K2 had an accuracy of 79%, 77%, and 57%, respectively [42].

Various lines of evidence suggest that different virulence factors of K. pneumoniae are associated with specific infections (Table 1): serotypes K1 and K2 and the ability to metabolize allantoin with liver abscess; yersiniabactin and salmochelin with RTI; type 1 fimbriae with UTI; type 3 fimbriae with infections associated with medical devices through biofilm formation; and salmochelin and Klebsiella iron uptake system with invasive infection. Studies have shown that the inactivation of these virulence factors reduced the ability to cause infection in mouse models. Although this association, even in humans, the prevalence of these virulence factors varies and is not always present in isolates. We observed that many virulence factors coexist in hypervirulent strains, such as the hypervirulence markers aerobactin, salmochelin, and regulator of mucoid phenotype A, as well as those commonly found in classical strains (yersiniabactin, type 1 fimbriae, and type 3 fimbriae), which possibly increases the ability to cause infection.

Table 1.

Main virulence factors in Klebsiella pneumoniae reported in different infections

| Virulence factor | Type/function | Target genes | Associated/correlated infection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsule | Capsular serotype K1; prevents phagocytosis, opsonization, the action of antimicrobial peptides and prevents activation of the immune system | magA | Liver abscessa | [40] |

| Capsular serotype K2; prevents phagocytosis, opsonization, the action of antimicrobial peptides and prevents activation of the immune system | k2A | Liver abscessa | [40] | |

| Regulator of mucoid phenotype A; increases capsule production and is responsible for the hypermucoviscosity phenotype | rmpA/rmpA2 | Liver abscessb | [32] | |

| Meningitisb | [50] | |||

| Invasive infectiona | [57] | |||

| Respiratory tract infectionb | [56] | |||

| Fimbriae | Type 1 fimbriae; adhesion | fimH | Urinary tract infectiona | [74] |

| Type 3 fimbriae; adhesion and biofilm formation | mrkD | Infections associated with medical devicesa | [74, 76, 79] | |

| Siderophores | Aerobactin; iron uptake | iucA, iucB, iucC, and iucD | Liver abscessa | [37] |

| Bacteremia/Bloodstream infectionb | [47] | |||

| Meningitisb | [50] | |||

| Yersiniabactin; iron uptake | ybtA, ybtS, irp1, irp2, and fyuA | Bacteremia/Bloodstream infectionb | [47] | |

| Invasive infectiona | [57] | |||

| Respiratory tract infectiona | [89] | |||

| Salmochelin; iron uptake | iroB and iroN | Invasive infectiona | [57, 92] | |

| Liver abscessb | [43] | |||

| Respiratory tract infectiona | [92, 120, 121] | |||

| Klebsiella Iron uptake system | Involved in the acquisition of iron | kfu | Invasive infectiona | [123] |

| Liver abscessb | [43] | |||

| Urinary tract infectionb | [65] | |||

| Allantoin metabolism | Involved in utilizing allantoin as an alternative source of nitrogen and carbon | allS | Liver abscessa | [127] |

| Bacteremia/Bloodstream infectionb | [47] |

aVirulence factor associated with infection based on in vitro or in vivo studies

bPresence of virulence factor in > 50% of cases

New studies should better characterize K. pneumoniae virulence, avoiding the limitation of focusing solely on a few virulence mechanisms. It was noted that salmochelin, a crucial virulence factor, has been little investigated in isolates from different infection types. Additionally, isolates from uncommon infection sites should be thoroughly characterized, and the prevalence of virulence factors must be estimated. For instance, there is a scarcity of studies that have explored the virulence of K. pneumoniae from meningitis cases. Finally, most studies that characterize virulence factors in K. pneumoniae described to date are in Asia, especially China, Japan, and Taiwan. Therefore, more studies are required to determine the real prevalence of virulence factors in K. pneumoniae from different infections in different geographic regions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)—Brasil [grant code 001]. Adriano S. S. Monteiro acknowledges the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (FAPESB) for the Ph.D. scholarships.

Author Contributions

Adriano de Souza Santos Monteiro did the literature search, data analysis, and drafted it; Soraia Machado Cordeiro had the idea of the article and drafted it; and the work was critically revised by Joice Neves Reis Pedreira.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts/competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, Gupta RS. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. Nov., Morgane. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:5575–5599. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martínez J, Martínez L, Rosenblueth M, Silva J, Martínez-Romero E. How are gene sequence analyses modifying bacterial taxonomy? case Klebsiella Int Microbiol. 2004;7:261–268. doi: 10.2436/im.v7i4.9481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park EA, Kim YT, Cho JH, Ryu S, Lee JH. Characterization and genome analysis of novel bacteriophages infecting the opportunistic human pathogens Klebsiella oxytoca and K. pneumoniae. Arch Virol. 2017;162:1129–1139. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng J, Zhou M, Nobrega DB, et al. Genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology of outbreaks of Klebsiella pneumoniae mastitis on two large Chinese dairy farms. J Dairy Sci. 2021;104:762–775. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-19325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzouvelekis LS, Miriagou V, Kotsakis SD, et al. KPC-producing, multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence Type 258 as a typical opportunistic pathogen. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5144–5146. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01052-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinz E, Brindle R, Morgan-McCalla A, Peters K, Thomson NR. Caribbean multi-centre study of Klebsiella pneumoniae: whole-genome sequencing, antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors. Microb Genom. 2019 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomakova DK, Hsiao CB, Beanan JM, et al. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:981–989. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S, Aoyama T, Uejima Y, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess due to hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a 14-year-old boy. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80:629–661. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsay RW, Siu LK, Fung CP, Chang FY. Characteristics of bacteremia between community-acquired and nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Ferrer S, Peñaloza HF, Budnick JA, et al. Finding order in the chaos: outstanding questions in Klebsiella pneumoniae pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2021;89:e00693–e720. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00693-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Guo J. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hypermucoviscous and aerobactin positive) infection over 6 years in the elderly in China: antimicrobial resistance patterns, molecular epidemiology and risk factor. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12941-018-0302-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Zhao C, Wang Q, et al. High prevalence of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in China: geographic distribution, clinical characteristics, and antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:6115–6120. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01127-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shon AS, Bajwa RPS, Russo TA. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence. 2013;4:107–118. doi: 10.4161/viru.22718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafat C, Messika J, Barnaud G, et al. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae, a 5-year study in a French ICU. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67:1083–1089. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto H, Iijima A, Kawamura K, Matsuzawa Y, Suzuki M, Arakawa Y. Fatal fulminant community-acquired pneumonia caused by hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae K2-ST86. Medicine. 2020;99:e20360. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coutinho RL, Visconde MF, Descio FJ, et al. Community-acquired invasive liver abscess syndrome caused by a K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate in Brazil: a case report of hypervirulent ST23. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:970–971. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu WL, Ko WC, Cheng KC, et al. Association between rmpA and magA genes and clinical syndromes caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1351–1358. doi: 10.1086/503420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oikonomou KG, Aye M. Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess: a case series of six Asian patients. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:1028–1033. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.905191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maruki T, Taniyama D, Tsuchiya Y, Adachi T. Breakthrough and persistent bacteremia due to serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae in an immunocompetent patient. IDCases. 2020;21:e00893. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaidullina E, Shelenkov A, Yanushevich Y, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and genomic characterization of OXA-48- and CTX-M-15-Co-producing hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae ST23 recovered from nosocomial outbreak. Antibiotics. 2020;9:862. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9120862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu D, Dong N, Zheng Z, et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: a molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:37–46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao H, Qin S, Chen S, Shen J, Du XD. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30628-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankar C, Jacob JJ, Vasudevan K, et al. Emergence of multidrug resistant hypervirulent ST23 Klebsiella pneumoniae: multidrug resistant plasmid acquisition drives evolution. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.575289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Marimuthu K, Teo J, et al. Acquisition of plasmid with carbapenem-resistance gene bla KPC2 in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Singapore Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:549–559. doi: 10.3201/eid2603.191230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman MF, Mayer Bridwell AE, Scott NE, et al. A promising bioconjugate vaccine against hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:18655–18663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907833116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cryz SJ, Furer E, Germanier R. Safety and immunogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae K1 capsular polysaccharide vaccine in humans. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:665–671. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edelman R, Talor DN, Wasserman SS, et al. Phase 1 trial of a 24-valent Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide vaccine and an eight-valent Pseudomonas O-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine administered simultaneously. Vaccine. 1994;12:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(94)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravinder M, Liao K-S, Cheng Y-Y, et al. A synthetic carbohydrate-protein conjugate vaccine candidate against Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype K2. J Org Chem. 2020;85:15964–15997. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitfield C. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:39–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyres KL, Wick RR, Gorrie C, et al. Identification of Klebsiella capsule synthesis loci from whole genome data. Microb Genom. 2016;2:e000102. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao CH, Huang YT, Chang CY, Hsu HS, Hsueh PR. Capsular serotypes and multilocus sequence types of bacteremic Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates associated with different types of infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:365–369. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1964-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Struve C, Roe CC, Stegger M, et al. Mapping the evolution of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. MBio. 2015;6:e00630–e715. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00630-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung SW, Chae HJ, Park YJ, et al. Microbiological and clinical characteristics of bacteraemia caused by the hypermucoviscosity phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:334–340. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin TL, Hsieh PF, Huang YT, et al. Isolation of a bacteriophage and its depolymerase specific for K1 capsule of Klebsiella pneumoniae: implication in typing and treatment. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1734–1744. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei DD, Wan Deng Liu LGQY. Emergence of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae hypervirulent clone of capsular serotype K1 that belongs to sequence type 11 in mainland China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;85:192–194. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan TY, Ong M, Cheng Y, Ng LSY. Hypermucoviscosity, rmpA, and aerobactin are associated with community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremic isolates causing liver abscess in Singapore. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molton JS, Lee IR, Bertrand D, et al. Stool metagenome analysis of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess and their domestic partners. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;107:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo Y, Wang Y, Ye L, Yang J. Molecular epidemiology and virulence factors of pyogenic liver abscess causing Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O818–O824. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeh KM, Chiu SK, Lin CL, et al. Surface antigens contribute differently to the pathophysiological features in serotype K1 and K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from liver abscesses. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:4. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0085-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumabe A, Kenzaka T. String test of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia. QJM. 2014;107:1053–1053. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo TA, Olson R, Fang CT, et al. Identification of biomarkers for differentiation of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from classical K pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00776-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee IR, Molton JS, Wyres KL, et al. Differential host susceptibility and bacterial virulence factors driving Klebsiella liver abscess in an ethnically diverse population. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29316. doi: 10.1038/srep29316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin JC, Koh T, Lee N, et al. Genotypes and virulence in serotype K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae from liver abscess and non-infectious carriers in Hong Kong. Singapore Taiwan Gut Pathog. 2014;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cubero M, Grau I, Tubau F, et al. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clones causing bacteraemia in adults in a teaching hospital in Barcelona, Spain (2007–2013) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Namikawa H, Niki M, Niki M, et al. Clinical and virulence factors related to the 30-day mortality of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia at a tertiary hospital: a case–control study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:2291–2297. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03676-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou M, Lan Y, Wang S, et al. Epidemiology and molecular characteristics of the type VI secretion system in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from bloodstream infections. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jcla.23459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lan Y, Zhou M, Jian Z, Yan Q, Wang S, Liu W. Prevalence of pks gene cluster and characteristics of Klebsiella pneumonia-induced bloodstream infections. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22838. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan JJ, Zheng PX, Wang MC, Tsai SH, Wang LR, Wu JJ. Allocation of Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream isolates into four distinct groups by ompK36 typing in a Taiwanese university hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:3256–3263. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01152-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku YH, Chuang YC, Chen CC, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates from meningitis: epidemiology. Virulence Antibiot Res Sci Rep. 2017;7:6634. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06878-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsu CR, Lin TL, Chen YC, Chou HC, Wang JT. The role of Klebsiella pneumoniae rmpA in capsular polysaccharide synthesis and virulence revisited. Microbiology. 2011;157:3446–3457. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.050336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivero A, Gomez E, Alland D, Huang DB, Chiang T. K2 Serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae causing a liver abscess associated with infective endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:639–641. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01779-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin WH, Wang MC, Tseng CC, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing community-acquired urinary tract infections. Infection. 2010;38:459–464. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Remya PA, Shanthi M, Sekar U. Characterisation of virulence genes associated with pathogenicity in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2019;37:210–218. doi: 10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_19_157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caneiras C, Lito L, Melo-Cristino J, Duarte A. Community- and hospital-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary tract infections in Portugal: virulence and antibiotic resistance. Microorganisms. 2019;7:138. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7050138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shao C, Wang W, Liu S, Zhang Z, Jiang M, Zhang F. Molecular epidemiology and drug resistant mechanism of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in elderly patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Front Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.669173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holt KE, Wertheim H, Zadoks RN, et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E3574–E3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501049112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu CC, Huang YJ, Fung CP, Peng HL. Regulation of the Klebsiella pneumoniae Kpc fimbriae by the site-specific recombinase KpcI. Microbiology. 2010;156:1983–1992. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alcántar-Curiel MD, Blackburn D, Saldaña Z, et al. Multi-functional analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae fimbrial types in adherence and biofilm formation. Virulence. 2013;4:129–138. doi: 10.4161/viru.22974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang YJ, Liao HW, Wu CC, Peng HL. MrkF is a component of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Struve C, Bojer M, Krogfelt KA. Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae type 1 fimbriae by detection of phase variation during colonization and infection and impact on virulence. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4055–4065. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00494-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Araújo BF, Ferreira ML, de Campos PA, et al. Hypervirulence and biofilm production in KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae CG258 isolated in Brazil. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67:523–528. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang ZC, Huang CJ, Huang YJ, Wu CC, Peng HL. FimK regulation on the expression of type 1 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43S3. Microbiology. 2013;159:1402–1415. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.067793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stahlhut SG, Chattopadhyay S, Kisiela DI, et al. Structural and population characterization of MrkD, the adhesive subunit of type 3 fimbriae. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:5602–5613. doi: 10.1128/JB.00753-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marques C, Menezes J, Belas A, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae causing urinary tract infections in companion animals and humans: population structure, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:594–602. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bandeira M, Carvalho P, Duarte A, Jordao L. Exploring dangerous connections between Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms and healthcare-associated infections. Pathogens. 2014;3:720–731. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3030720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El Fertas-Aissani R, Messai Y, Alouache S, Bakour R. Virulence profiles and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from different clinical specimens. Pathol Biol. 2013;61:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eghbalpoor F, Habibi M, Azizi O, Asadi Karam MR, Bouzari S. Antibiotic resistance, virulence and genetic diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae in community-and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2019;66:349–366. doi: 10.1556/030.66.2019.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tchesnokova V, Aprikian P, Kisiela D, et al. Type 1 fimbrial adhesin fimh elicits an immune response that enhances cell adhesion of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3895–3904. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05169-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sauer MM, Jakob RP, Eras J, et al. Catch-bond mechanism of the bacterial adhesin FimH. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10738. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou G, Mo WJ, Sebbel P, et al. Uroplakin Ia is the urothelial receptor for uropathogenic Escherichia coli: evidence from in vitro FimH binding. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4095–4103. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:269–284. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carpenter AR, Becknell MB, Ching CB, et al. Uroplakin 1b is critical in urinary tract development and urothelial differentiation and homeostasis. Kidney Int. 2016;89:612–624. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Struve C, Bojer M, Krogfelt KA. Identification of a conserved chromosomal region encoding Klebsiella pneumoniae Type 1 and Type 3 fimbriae and assessment of the role of fimbriae in pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5016–5024. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00585-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vuotto C, Longo F, Pascolini C, et al. Biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary strains. J Appl Microbiol. 2017;123:1003–1018. doi: 10.1111/jam.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson JG, Murphy CN, Sippy J, Johnson TJ, Clegg S. Type 3 fimbriae and biofilm formation are regulated by the transcriptional regulators MrkHI in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3453–3460. doi: 10.1128/JB.00286-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fu L, Huang M, Zhang X, et al. Frequency of virulence factors in high biofilm formation bla producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from hospitals. Microb Pathog. 2018;116:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murphy CN, Mortensen MS, Krogfelt KA, Clegg S. Role of Klebsiella pneumoniae Type 1 and Type 3 fimbriae in colonizing silicone tubes implanted into the bladders of mice as a model of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3009–3017. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00348-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bellifa S, Hassaine H, Balestrino D, et al. Evaluation of biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from medical devices at the university hospital of Tlemcen. Algeria Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:5558–5564. doi: 10.5897/AJMR12.2331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Singhai M, Malik A, Shahid M, Malik M, Goyal R. A study on device-related infections with special reference to biofilm production and antibiotic resistance. J Glob Infect Dis. 2012;4:193. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.103896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maharjan G, Khadka P, Siddhi Shilpakar G, Chapagain G, Dhungana GR. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection and obstinate biofilm producers. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2018/7624857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Niveditha SN. The isolation and the biofilm formation of uropathogens in the patients with catheter associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1478. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4367.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Surekha S, Lamiyan AK, Gupta V. Antibiotic resistant biofilms and the quest for novel therapeutic strategies. Indian J Microbiol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s12088-023-01138-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lewis K. Multidrug tolerance of biofilms and persister cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;322:107–131. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Holden VI, Bachman MA. Diverging roles of bacterial siderophores during infection. Metallomics. 2015;7:986–995. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00333K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Compain F, Babosan A, Brisse S, et al. Multiplex PCR for detection of seven virulence factors and K1/K2 capsular serotypes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:4377–4380. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02316-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen T, Dong G, Zhang S, et al. Effects of iron on the growth, biofilm formation and virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing liver abscess. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:36. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01727-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bachman MA, Oyler JE, Burns SH, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae yersiniabactin promotes respiratory tract infection through evasion of lipocalin 2. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3309–3316. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05114-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Russo TA, Olson R, MacDonald U, Beanan J, Davidsona BA. Aerobactin, but not yersiniabactin, salmochelin, or enterobactin, enables the growth/survival of hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae ex vivo and in vivo. Infect Immun. 2015;83:3325–3333. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00430-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Russo TA, Shon AS, Beanan JM, et al. Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae secretes more and more active iron-acquisition molecules than “Classical” K. pneumoniae thereby enhancing its virulence spellberg B, ed. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fischbach MA, Lin H, Zhou L, et al. The pathogen-associated iroA gene cluster mediates bacterial evasion of lipocalin 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16502–16507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604636103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Russo TA, Olson R, MacDonald U, et al. Aerobactin mediates virulence and accounts for increased siderophore production under iron-limiting conditions by hypervirulent (Hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2014;82:2356–2367. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01667-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Perry RD, Balbo PB, Jones HA, Fetherston JD, DeMoll E. Yersiniabactin from Yersinia pestis: biochemical characterization of the siderophore and its role in iron transport and regulation. Microbiology. 1999;145:1181–1190. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yan Q, Zhou M, Zou M, Liu WE. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae induced ventilator-associated pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients in China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhu Z, Huang H, Xu Y, et al. Emergence and genomics of OXA-232-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a hospital, Yancheng, China. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;26:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sellera FP, Lopes R, Monte DFM, et al. Genomic analysis of multidrug-resistant CTX-M-15-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae belonging to the highly successful ST15 clone isolated from a dog with chronic otitis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:659–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hao Z, Duan J, Liu L, et al. Prevalence of community-acquired, Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Wenzhou. China Microb Drug Resist. 2020;26:21–27. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhao Y, Zhang S, Fang R, et al. Dynamic epidemiology and virulence characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Wenzhou, China from 2003 to 2016. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:931–940. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S243032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rossi B, Gasperini ML, Leflon-Guibout V, et al. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in cryptogenic liver abscesses, Paris. France Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:221–229. doi: 10.3201/eid2402.170957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wasfi R, Elkhatib WF, Ashour HM. Molecular typing and virulence analysis of multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates recovered from Egyptian hospitals. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38929. doi: 10.1038/srep38929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hu D, Li Y, Ren P, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hypervirulent carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.661218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Scavuzzi AML, Firmo EF, de Oliveira ÉM, de Lopes ACS. Emergence of blaNDM-1 associated with the aac(6’)-Ib-cr, acrB, cps, and mrkD genes in a clinical isolate of multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from Recife-PE Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019 doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0352-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nguyen LP, Pinto NA, Vu TN, et al. In vitro activity of a novel siderophore-cephalosporin, GT-1 and serine-Type β-lactamase inhibitor, GT-055, against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. Panel Strains Antibiot. 2020;9:267. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9050267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sonnevend Á, Ghazawi A, Hashmey R, et al. Multihospital occurrence of pan-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 147 with an IS Ecp1-directed bla OXA-181 insertion in the mgrB gene in the United Arab Emirates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00418-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lin ZW, Zheng JX, Bai B, et al. Characteristics of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: does low expression of rmpA contribute to the absence of hypervirulence? Front Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shah RK, Ni ZH, Sun XY, Wang GQ, Li F. The determination and correlation of various virulence genes, ESBL, serum bactericidal effect and biofilm formation of clinical isolated classical Klebsiella pneumoniae and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from respiratory tract infected patients. Pol J Microbiol. 2017;66:501–508. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.7042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bailey DC, Alexander E, Rice MR, et al. Structural and functional delineation of aerobactin biosynthesis in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:7841–7852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Khalil MAF, Hager R, Abd-El Reheem F, et al. A study of the virulence traits of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in a Galleria mellonella model. Microb Drug Resist. 2019;25:1063–1071. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li J, Ren J, Wang W, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae induced bloodstream infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37:679–689. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3160-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu Z, Gu Y, Li X, et al. Identification and characterization of NDM-1-producing hypervirulent (Hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. Ann Lab Med. 2019;39:167–175. doi: 10.3343/alm.2019.39.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Davies YM, Cunha MPV, Oliveira MGX, et al. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from passerine and psittacine birds. Avian Pathol. 2016;45:194–201. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2016.1142066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ganz T. Iron and infection. Int J Hematol. 2018;107:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kim YJ, Il KS, Kim YR, et al. Virulence factors and clinical patterns of hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from urine. Infect Dis. 2017;49:178–184. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2016.1244611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tian D, Wang M, Zhou Y, Hu D, Ou HY, Jiang X. Genetic diversity and evolution of the virulence plasmids encoding aerobactin and salmochelin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Virulence. 2021;12:1323–1333. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1924019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liu C, Du P, Xiao N, Ji F, Russo TA, Guo J. Hypervirulent klebsiella pneumoniae is emerging as an increasingly prevalent K. pneumoniae pathotype responsible for nosocomial and healthcare-associated infections in Beijing China. Virulence. 2020;11:1215–1224. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2020.1809322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Crouch MLV, Castor M, Karlinsey JE, Kalhorn T, Fang FC. Biosynthesis and IroC-dependent export of the siderophore salmochelin are essential for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:971–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hantke K, Nicholson G, Rabsch W, Winkelmann G. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3677–3682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737682100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang S, Zhang X, Wu Q, et al. Clinical, microbiological, and molecular epidemiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced pyogenic liver abscess in southeastern China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:166. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0615-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Caza M, Lépine F, Milot S, Dozois CM. Specific roles of the iroBCDEN genes in virulence of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 strain and in production of salmochelins. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3539–3549. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00455-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bachman MA, Lenio S, Schmidt L, Oyler JE, Weiser JN. Interaction of lipocalin 2 transferrin, and siderophores determines the replicative niche of klebsiella pneumoniae during pneumonia hultgren SJ, ed. MBio. 2012 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00224-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gao Q, Shen Z, Qin J, Liu Y, Li M. Antimicrobial resistance and pathogenicity determination of community-acquired hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 2020;26:1195–1200. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ma L, Fang C, Lee C, Shun C, Wang J. Genomic heterogeneity in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains is associated with primary pyogenic liver abscess and metastatic infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:117–128. doi: 10.1086/430619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Imai K, Ishibashi N, Kodana M, et al. Clinical characteristics in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola, and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae: a comparative study, Japan, 2014–2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:946. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4498-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Aljanaby AAJ, Alhasani AHA. Virulence factors and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of multidrug resistance Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from different clinical infections. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2016;10:829–843. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2016.8051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Azevedo PAA, Furlan JPR, Gonçalves GB, et al. Molecular characterisation of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae belonging to CC258 isolated from outpatients with urinary tract infection in Brazil. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;18:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chou HC, Lee CZ, Ma LC, Fang CT, Chang SC, Wang JT. Isolation of a chromosomal region of Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with allantoin metabolism and liver infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3783–3792. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3783-3792.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Decre D, Verdet C, Emirian A, et al. Emerging severe and fatal infections due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in two university hospitals in France. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3012–3014. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00676-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.