Abstract

Active nuclear import of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) preintegration complex (PIC) is essential for the productive infection of nondividing cells. Nuclear import of the PIC is mediated by the HIV-1 matrix protein, which also plays several critical roles during viral entry and possibly during virion production facilitating the export of Pr55Gag and genomic RNA. Using a yeast two-hybrid screen, we identified a novel human virion-associated matrix-interacting protein (VAN) that is highly conserved in vertebrates and expressed in most human tissues. Its expression is upregulated upon activation of CD4+ T cells. VAN is efficiently incorporated into HIV-1 virions and, like matrix, shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Furthermore, overexpression of VAN significantly inhibits HIV-1 replication in tissue culture. We propose that VAN regulates matrix nuclear localization and, by extension, both nuclear import of the PIC and export of Pr55Gag and viral genomic RNA during virion production. Our data suggest that this regulatory mechanism reflects a more global process for regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport.

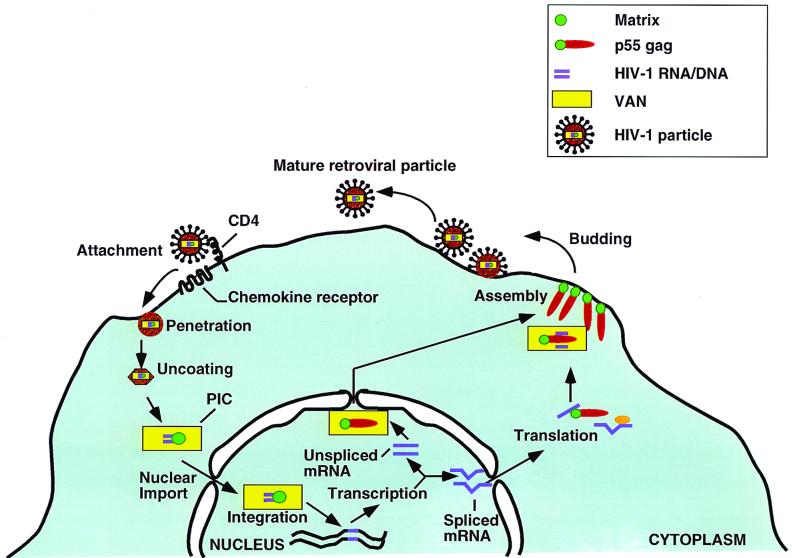

The complicated life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) involves a dynamic interplay between viral and host factors. The ability of the virus to access the nucleus via active nuclear import is mediated by both viral and host proteins. This function distinguishes HIV-1 from oncoretroviruses, which rely on nuclear envelope disassembly during cell division for nuclear import (36, 53). HIV-1's primary targets in vivo are CD4+ T cells, most of which are resting, and terminally differentiated tissue macrophages, rendering the ability of HIV-1 to enter the nucleus of nondividing cells critical for viral pathogenesis and disease progression (41). Hence, there is great interest in understanding nuclear import of the HIV-1 preintegration complex (PIC), which consists of viral DNA and certain viral and host proteins (8, 42). Several viral proteins, including the matrix protein, are implicated in PIC nuclear localization (7, 28, 33, 60).

Matrix, a key component of the HIV-1 PIC, contributes to nuclear localization of the PIC and plays other crucial roles throughout the HIV-1 life cycle (6, 15, 24, 38, 50, 67). Matrix is a 17-kDa myristoylated protein derived from the extreme N terminus of the Gag precursor polyprotein (Pr55Gag). Nuclear import of matrix is believed to be mediated by its two nuclear localization signals (NLSs) that resemble the canonical simian virus 40 T-antigen NLS (7, 60). However, the role of these NLSs and the mechanism of nuclear import are matters of debate (7, 21–23, 28, 52, 60). Recently, a nuclear export activity was suggested for matrix (16) which could override its NLS, facilitating nuclear export of unspliced viral RNA and cytoplasmic retention of Pr55Gag during virion production. Late in the viral life cycle, prior to cleavage as part of Pr55Gag, matrix orchestrates virion assembly and release by targeting the Gag proteins to the host cell membrane. The Gag proteins recruit viral genomic RNA, as well as viral and host cell proteins, into the newly budding virion (17, 57, 68). Soon after assembly, following its incorporation into the virion, Pr55Gag is cleaved by the HIV-1 protease to generate mature p17 matrix (MA), p24 capsid (CA), p7 nucleocapsid, and p6.

As obligate intracellular parasites, viruses often recruit help from host cell factors. Interactions of matrix with cellular proteins have previously been described. These include HO3, a putative tRNA synthetase (40), HEED, the human homolog of mouse eed (51), translation elongation factor 1-alpha (13), and hIF2, a human homolog of bacterial translation initiation factor 2 (64). However, it remains unclear how these host proteins contribute to matrix's role in viral replication, and our understanding of how matrix operates is still incomplete.

To elucidate the mechanisms of matrix function, we looked for new cellular partners for matrix using a two-hybrid screen with matrix as bait and a human activated T-cell cDNA library as prey. We isolated a putative partial open reading frame (ORF) of unknown function that we designated virion-associated nuclear shuttling protein, or VAN. VAN is evolutionarily highly conserved in vertebrates, and its transcript is present in all human tissues tested. Here, we describe the characterization of the matrix-VAN interaction, VAN's nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling capacity, and its potential role in the viral life cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two-hybrid screen.

The two-hybrid screen was performed in a triple-reporter strain, Saccharomyces cerevisiae MaV103, bearing GAL promoter-dependent URA3, HIS3, and lacZ genes (MATa ade2-101 leu2-3,112 trp1Δ1 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ pGAL1:HIS3 at lys2 pGAL1:lacZ at unknown locus SPAL10:URA3) (59). As bait we used the matrix protein derived from HIV-1YU2, a macrophagetropic primary isolate derived from the brain of a patient suffering from AIDS dementia (63), fused at its N terminus to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GAL4DBD) of pPC97 (11). This vector contains the GAL4DBD and LEU2 selectable marker. Full-length YU2 MA (pKG104), JR-CSF MA, NL4-3 MA, AD MA, YU2 Vpr, YU2 Pr55Gag, LAI Pr55Gag, LAI Vpr, and LAI Nef were generated via standard PCR using the corresponding proviral DNAs as templates and appropriate primers. The PCR products were digested and cloned in frame into the SalI/BglII or SalI/NotI sites of pPC97. The inserts were sequenced, and protein expression was confirmed by Western analysis. The two-hybrid bait plasmid used for the initial screen was pKG104. The activation domain library, Alala2 (kindly provided by Joshua La Baer, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Mass.) contains cDNA derived from phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated T cells fused to the coding region of the GAL4 transactivation domain (GAL4TAD) of pPC86, which has the TRP1 selectable marker.

Growth and manipulation of the yeast strain were done according to standard procedures (54, 55). The bait and library plasmids were transformed into MaV103. Transformants were first selected for leucine and tryptophan prototrophy. The colonies were then replica plated onto histidine-deficient synthetic complete medium (SC−His) plates containing 30 mM 3-aminotriazole (3AT) and on SC−Ura plates. The His+ colonies were also tested for β-galactosidase (β-Gal) expression on nitrocellulose filters (5). In the event that a library-encoded protein interacts with the bait protein, transcription is activated from the reporter genes giving His+, Ura+ (only for strong activators), 5-fluoro-orotic acid-sensitive, β-Gal-positive phenotypes which can be detected on appropriate selective media.

Of the ∼1.5 million colonies screened, 184 were His+, indicating that they might contain library cDNAs encoding matrix-interacting proteins. Therefore, we performed a secondary screen on these colonies, assaying for activation of the URA3 and lacZ genes by examining uracil prototrophy, 5-fluoro-orotic acid sensitivity, and β-Gal activity. Of the initially identified 184 His+ clones, 28 were positive for all three reporters. Plasmids were recovered from these 28 putative interactors, cotransformed into yeast with the bait plasmid, and screened again for the ability to activate transcription from the three reporters. Five such clones were isolated, and all contained the matrix-interacting partial library cDNA-encoded protein, designated VAN-C (C terminus of VAN).

We were unable to test full-length VAN in the yeast two-hybrid system, as full-length VAN-GAL4TAD fusion protein was undetectable by immunoblotting. To confirm that the interaction between VAN and matrix occurs in vivo, we attempted coimmunoprecipitation. However, in our hands, heterologous VAN expressed in both bacteria and mammalian cells was insoluble in a variety of nonionic detergents tested, precluding such analysis.

Identification of full-length cDNA.

Full-length VAN cDNA, pCMVSport-VAN (pKG148), was isolated by screening a human leukocyte cDNA library (SuperScript human leukocyte cDNA library; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) using the GeneTrapper cDNA positive selection system (Life Technologies catalog no. 10421-014) as instructed by the manufacturer. The cDNAs identified were tested by Southern blotting for the ability to hybridize to a VAN-C-derived probe. Of the positive cDNAs, the longest was 3.3 kb (pKG148). It contains 262 bp of untranslated leader sequence followed by an ATG in a relatively good Kozak context with an in-frame stop codon nine nucleotides upstream of the ATG. The cDNA encoded a predicted ORF of 637 amino acids corresponding to a protein of ∼72 kDa. The gene has been mapped to the long arm of chromosome 5 by the NCBI Unigene database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/index.html).

Generation of plasmids, cell lines, and antibodies.

An AvrII/NotI fragment of full-length VAN cDNA was cut out of pKG148 and cloned into the NheI/NotI sites of pCEP4 (Invitrogen) to generate pKG123 (pCEP4-VAN), the mammalian VAN expression plasmid. A second PCR product corresponding to the two-hybrid interacting partial cDNA was generated with KpnI and XhoI sites at its ends (using primers M27pCEP4-N [AATCGGGGTACCACCATGGGCGGCCGCAGAATTCGGCACGAGAGT] and M27pCEP4-C [TACCGCTCGAGTAGCACTAGTCTCGAGTTT]). The PCR product was then digested with KpnI/XhoI and ligated into the same sites in pCEP4 to generate pKG125 (pCEP4-VAN-C), the VAN-C mammalian expression vector.

HeLa T4 cells expressing CD4 on their surface (National Institutes of Health [NIH] AIDS Reagent Program) and 293T cells (Beatrice Hahn, American Type Culture Collection) were plated at 40% confluency 18 to 24 h prior to transfection. The cells were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's guidelines with pCEP4, pCEP4-VAN, and pCEP4-VAN-C; 48 h postinfection, the cells were split into medium containing hygromycin B (200 μg/ml). A confluent hygromycin B-resistant cell monolayer was obtained after 3 to 4 weeks of passaging the cells in the presence of the drug. The cell populations thus established were tested for protein expression by immunoblotting as well as by immunofluorescence in the case of HeLa T4 cells. HeLa T4 cells overexpressing VAN expressed ∼30 times more protein than pCEP4 transfectants, while 293T cells expressed ∼8 times more VAN protein than pCEP4-transfected cells. Overexpression of VAN or VAN-C in these cells did not cause any changes in gross morphology or growth characteristics of the transfected cell populations.

A PCR product was generated from the 5′ end of pKG148 to introduce an NdeI site in frame with the VAN initiator ATG. Primers used were JB1165 (TGCTCATTCTTGTGCACCTTGGATGCC; 3′ primer for cloning N terminus of VAN into pET-15b, ApaL1 site underlined) and JB1166 (GGTACCCAGCTGAATTCCATATGGAAGGGAGAGGACCG; 5′ primer, NdeI site underlined). This product was digested with NdeI/ApaLI and, together with an ApaLI/XhoI fragment encoding the 3′ end of VAN from pKG148, ligated into pET15b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) digested with NdeI/XhoI. This generated pKG121, used to express His6-tagged full-length VAN in bacteria, which was purified under denaturing conditions (8 M urea) over a nickel chelating column. Polyclonal antisera to VAN were generated by injecting the fusion protein into rabbits. Antisera were affinity purified in accordance with a previously published protocol (56).

Monocytes and macrophages were purified from peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) using a previously described panning protocol (25, 39). Resting CD4+ T cells were purified and activated as described elsewhere (12).

GST-MA interaction with VAN-C′.

A 1,300-bp fragment obtained from an XhoI/XmnI partial digest of pCMV Sport-VAN was ligated into the pET30c vector backbone (Novagen) digested with XhoI/EcoRV to generate pKG122, the His6-tagged VAN-C′ expression plasmid. The MA insert was excised from pKG104 by digesting it with SalI/NotI. The resulting insert was ligated into pGEX4-T2 (Pharmacia Biotech catalog no. 27-4581-01) also digested with SalI/NotI to generate pKG115, expression vector for glutathione S-transferase (GST)–MA fusion protein. Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with pGEX4T-2, pKG115, and pKG122 and assayed for protein expression upon induction. One hundred milliliters of a 1:50 dilution of an overnight culture started from a single transformant was incubated at 37°C. At A600 of ∼0.6, 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce protein expression. After induction for 3 h at 37°C, the cells were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min and the pellets were frozen at −80°C. The pellets were thawed, and the GST fusion proteins were resuspended in 5 ml of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], protease inhibitor cocktail [1,000× protease inhibitor cocktail contains 1 mg of leupeptin, 2 mg of antipain, 10 mg of benzamidine, 10,000 KIU of aprotinin, 1 mg of chymostatin, and 1 mg of pepstatin per ml plus 1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], while the VAN-C′-expressing lysates were resuspended in 5 ml of binding buffer (5 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], protease inhibitor cocktail). GST- or GST-MA-containing cell lysates were mixed with equal volumes of VAN-C′ cell lysates and incubated for 4 h at 4°C; 500 μl of 50% glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia Biotech) slurry was added to 500 μl of the lysate and incubated at 4°C for another 2 h. The beads were then washed three times: wash 1 with binding buffer; wash 2 with binding buffer with a final NaCl concentration of 350 mM, 400 mM, or 500 mM; and wash 3 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The beads were resuspended in 1× Laemmli buffer and subjected to standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western analysis. Recombinant VAN-C′, purified under denaturing conditions (8 M urea) over a nickel chelating column, was used as a size marker in lieu of the VAN-C-containing lysates used for the GST binding assay.

Northern analysis (human and mouse).

VAN-C was used as a template to generate a 32P-labeled probe as previously described (18) to probe a commercially available human multiple-tissue Northern blot (lots 53626 and 54756; Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) as instructed by the manufacturer. The lanes were normalized for equal amounts of β-actin prior to loading.

Identification of mouse and chicken cDNAs.

We used the BLAST algorithm to search the EST (expressed sequence tag) database and identified a number of overlapping mouse ESTs. We ordered four of these clones from the American Type Culture Collection and sequenced them. One of these (GenBank accession no. AA061107, from a mouse testis library) encoded a 2.4-kb insert that shared a high degree of identity with human VAN (hVAN) (P = 3.1e−55). The BLAST search also identified a chicken sequence in the 5′ untranslated region of the reported chicken proto-Ets protein sequence (GenBank accession no. M23688 [61]) that shared a high degree of homology to hVAN. We assume this transcript represents a chimeric cDNA.

Immunofluorescence.

HeLa cells (3 × 106) were plated onto coverslips in a six-well plate 18 to 24 h prior to transfection. The cells were transfected with Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies) the following day in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. At 48 h posttransfection, the coverslips were rinsed in PBS and then fixed in PBS–4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.2) for 20 min at room temperature. The coverslips were rinsed and permeabilized with PBS–0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Fixed, permeabilized cells were blocked with PBS–5% normal goat serum for 1 h. They were incubated with primary antibody(ies) diluted in the blocking solution overnight at 4°C, washed in PBS three times for 15 min each, and then incubated with secondary antibody(ies) also diluted in the blocking solution for 45 min at room temperature. Coverslips were washed twice in PBS, then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml; Sigma) in PBS for 5′, washed again in PBS, patted dry between two Kimwipes, mounted in Prolong mounting medium (Molecular Probes), and allowed to set at 4°C overnight prior to microscopic analysis. The antibodies were diluted as follows: affinity-purified anti-VAN, 1:50; anti-HIV IgIV (a human polyclonal antibody stock derived from HIV-1-seropositive individuals), 1:2,000; monoclonal antibody HA.11 (clone 16B12; Covance catalog no. MMS-101P), 1:2,000; anti-β-Gal (Life Technologies catalog no. 19929-017), 1:20; anti-p65 RelA (NFκB; Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc-109), 1:50; Cy3-conjugated affinity-purified goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories catalog no. 111-165-045), 1:5,000; anti-mouse IgG-fluorescein (Boehringer Mannheim catalog no. 1814222), 1:500; fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories catalog no. FI-1000), 1:100; and goat anti-human IgG-fluorescein conjugate (Pierce catalog no. 31530), 1:100.

Confocal microscopy.

For the subcellular localization of VAN and leptomycin B (LMB) studies, samples were acquired with the Bio-Rad MRC 600 confocal laser scanning microscope system utilizing COMOS software (version 6.03) on a Compaq Deskpro with a Pentium processor (Intel). A krypton-argon laser (Bio-Rad) with excitation at wavelengths of 488 and 568 nm was used to obtain optical sections. Narrow-band emission filters (525 and 605 nm) were used to eliminate channel cross talk, and the pinhole aperture was set to obtain 0.5-μm z-plane sections (as determined by full-width half-maximum intensity values). Slides were imaged with a 60× oil immersion planar apochromatic objective lens (numerical aperture, 1.4) through a Nikon Optiphot microscope. All images shown were representative of the entire field.

For the relocalization experiment, samples were imaged masked and acquired with the Noran Oz confocal laser scanning microscope system utilizing Intervision software (version 6.3) on a Silicon Graphics Indy R5000 platform. A krypton-argon laser (Omnichrome series 43) with excitation at 488 and 568 nm was used to obtain optical sections. Narrow-band emission filters (525 and 605 nm) were used to eliminate channel cross talk, and a 10-μm fixed slit was used to obtain 0.5-μm z-plane sections (as determined by full-width half-maximum intensity values). Slides were imaged with a 100× oil immersion planar apochromatic objective lens (numerical aperture, 1.35) through an Olympus IX-50 inverted microscope. Range check was used to determine optimal intensities for imaging. Two-dimensional analysis was performed utilizing Intervision software (Noran) to set brightness and contrast and adjust for deconvolution. Controls and experimental samples were treated identically.

Immunoblot analysis.

Typically, 107 cells were lysed in 100 μl of Laemmli buffer. Ten microliters of the cell lysate was run on a 12% SDS protein gel. Proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore) at 300 mA for 1.5 h at 4°C. The membrane was blocked with PBS–5% milk–0.05% Tween 20 and incubated with primary antibody at the appropriate concentration at 4°C overnight. The blot was washed three times for 15 min each in PBS–0.05% Tween 20 and then incubated with a 1:10,000 dilution of the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham) for 45 min. The blot was again washed three times, and antibody binding was detected by ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) immunoblotting detection reagents (Amersham). Antibodies were used at the following dilutions: murine anti-p17 HIV-1 monoclonal antibody (Immune Diagnostics, Inc., Bedford, Mass.), 1:1,000; affinity-purified rabbit anti-VAN, 1:100; anti-gp41 (T-32 hybridoma supernatant [a kind gift from Patricia Earl, NIH]; the epitope spans residues 597 to 613 of gp41 from HIV-1IIIB) 1:500; mouse anti-human HIV p24 monoclonal antibody (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.), 1:100; and monoclonal antiactin (clone AC-40; Sigma), 1:100.

Preparation and characterization of viral stocks.

All viral stocks were generated by transfecting 293T cells using a commercially available calcium phosphate DNA precipitation kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. HIV-1MN, HIV-1MNΔNEF, and HIV-1NL4-3 were grown in chronically infected H-9 cells as described elsewhere (4). HIV-1MNΔNEF contains a deletion starting at nucleotide 8805 and resuming at nucleotide 9064, deleting the start of Nef at nucleotide 8811. For viral growth curves, the proviral DNAs used were pLAI and pNL4-3, a kind gift from Keith Peden. Transfections were performed in 100-mM-diameter dishes at 30 to 50% confluency, and virus-containing supernatants were harvested and concentrated by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion 48 h posttransfection. Supernatants were then normalized for p24 content by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Coulter [Miami, Fla.] ELISA kit), and stored at −80°C. Recombinant vaccinia viruses, vp1287 (Pr55Gag), vp1290 (MA), and vp1289 (CA) were obtained from Virogenetics Corporation; vsc8 was a kind gift from Bernie Moss, NIH (10).

HIV-1 infection and viral growth curves.

HeLa T4 transfectants (106) were plated in each six-well plate. Each well was infected with 80 ng of p24 equivalents from HIV-1NL4-3- or HIV-1LAI-containing 293T cell supernatant for 3 h, after which the wells were washed six times with serum-free medium; 2 ml of fresh culture medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium 10% fetal calf serum 1% Pen-Strep, 2% l-glutamine) was added per well. To monitor viral replication, 200 μl was taken from each well at time zero and at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days postinfection and replaced with 200 μl of fresh culture medium. The supernatants were then analyzed by ELISA (Coulter ELISA kit) to determine the amount of p24 present as a measure of viral replication over an 8-day time course.

VAN in virions.

Virion preparations normalized for total protein content (determined by Lowry assay) were digested in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA for 18 h at 37°C either with or without subtilisin (1 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) (48, 49). The reactions were stopped with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (5 μg/ml, final concentration), and the treated virions were recovered by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose pad in PBS (Life Technologies) at 25,000 rpm for 1 h in an SW28Ti rotor (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). Treated virions were lysed in gel-loading buffer, applied to a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Novex, San Diego, Calif.), and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Microvesicles were prepared and treated in a similar manner (3). For semiquantitative immunoblot analysis, the VAN signal from known amounts of HIV-1MN (8 × 109 particles by p24 concentration) was compared to that of a dilution series of known amounts of full-length recombinant VAN fusion protein immobilized onto a polyvinylidene membrane (quantitated by amino acid analysis carried out on a Beckman System 6300 after hydrolysis with 6 N HCl as previously described [33a]).

VAN-C in virions.

293T cells were plated (1.5 × 106/10-cm-diameter petri dish) 18 to 24 h prior to transfection. The cells were cotransfected with VAN-C and proviral DNA plasmid (pHXB2/pAD) or empty vector, using a previously described method (2). At 48 h posttransfection, supernatants were harvested from the various cell cultures, and virions were purified as described elsewhere (9). Each fraction was tested for p24 antigen content to identify where the purified virus peaked; 20 ml of each fraction was then loaded onto a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by immunoblotting for the presence of matrix and VAN.

RESULTS

VAN, a new matrix partner.

To identify factors that interact with HIV-1 matrix and thereby mediate its functions, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen. We fused the matrix protein from HIV-1YU2, a macrophagetropic, primary patient isolate, to the C terminus of the GAL4DBD as bait. The library screened was derived from PHA-activated T-cell cDNA fused to the GAL4TAD. We identified five clones capable of activating transcription in a matrix-dependent manner. All five encoded a single partial cDNA corresponding to a putative partial ORF of unknown function (Fig. 1a) (GenBank accession no. D30755; recently isolated as Naf1 [Nef-associated factor 1] [27]) (see Discussion).

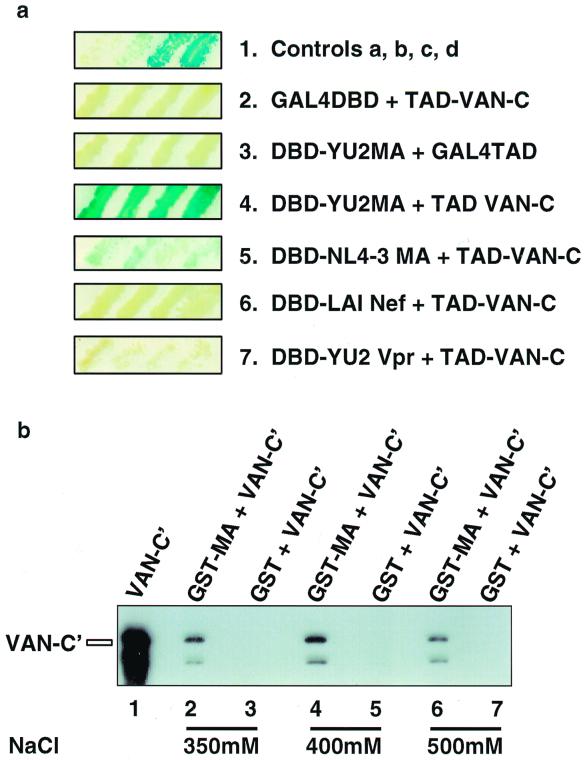

FIG. 1.

Matrix-VAN interaction. (a) Matrix interacts with VAN in the yeast two-hybrid system. In each case, four independent transformants were picked and tested for β-Gal activity. The first cDNA listed is fused to the GAL4DBD (in plasmid pPC97), while the second is fused to the GAL4TAD (in plasmid pPC86). 1, controls a to d (left to right) containing the following cDNA inserts: none/none, human retinoblastoma/E2F1, rat c-Fos/mouse c-Jun, and full-length GAL4/none, respectively; 2, none/VAN-C; 3, YU2 MA/none; 4, YU2 MA/VAN-C; 5, NL4-3 MA/VAN-C; 6, LAI Nef/VAN-C; 7, YU2 Vpr/VAN-C. (b) In vitro binding of GST-MA fusion protein to His6-tagged VAN-C′ is stable to 500 mM NaCl. Bacterially expressed GST-MA was immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads. Equal amounts of His6-tagged VAN-C′-containing bacterial lysates were incubated with GST and GST-MA immobilized on beads. The beads were washed, and the proteins that remained associated with the beads were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-His tag antibody. Recombinant VAN-C′, purified over a nickel chelating column under denaturing conditions, was used as a size marker in lane 1; its position is indicated by the bar on the left. The concentration of NaCl in each wash is indicated at the bottom.

To obtain the complete cDNA sequence, we screened a second cDNA library from human PBL, from which we identified a cDNA encoding a 72-kDa protein (VAN) and a partial cDNA encoding the C terminus of VAN (VAN-C) (Fig. 2).

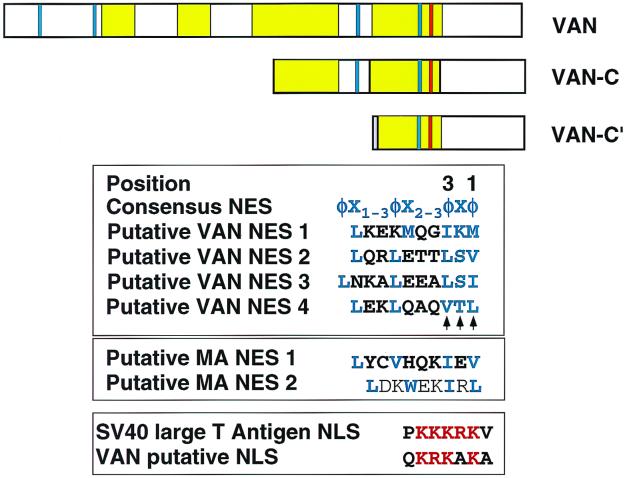

FIG. 2.

Sequence comparison. At the top are schematic representations of full-length VAN (amino acids 1 to 637), VAN-C (amino acids 312 to 637), and VAN-C′ (amino acids 468 to 637). Yellow regions highlight predicted coiled-coil domains, each red bar shows the putative NLS, blue bars depict putative NESs, and each purple bar shows the His6 tag. The consensus leucine-rich NES is shown in blue. Critical residues are the hydrophobic residues indicated as φ, usually leucine, at positions 1 and 3 (numbered from right to left as indicated) and additional hydrophobic residues at positions 6 and 7 and positions 9 to 11. The hydrophobic residues are interspersed with charged residues, serines or threonines marked as “Χ”. The arrowheads point to residues that were mutagenized to the sequence ASA. SV40, simian virus 40.

As controls to rule out nonspecific interactions, we tested VAN-C fused with HIV-1 Nef, HIV-1 Vpr, and full-length Pr55Gag baits in the two-hybrid system. Pr55Gag activated transcription, albeit somewhat weakly, compared with mature matrix; by contrast, Nef and Vpr failed to do so (Fig. 1a; Table 1), attesting to the specificity of VAN-C for matrix and Pr55Gag. Additionally, neither matrix fused to the GAL4DBD nor VAN-C fused to the GAL4TAD was capable of inducing transcription in the presence of an unfused GAL4TAD or unfused GAL4DBD, respectively (Fig. 1a).

TABLE 1.

Gag-VAN interaction in the yeast two-hybrid systema

| Bait | Interactor | SC−Leu−Trp− His+3AT | SC−Ura | β-Gal activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empty vector (pPC97)b | Empty vector (pPC86) | − | − | − |

| YU2 Vprb | VAN-C | − | − | − |

| LAI Nefb | VAN-C | − | − | − |

| Full-length GAL4c | Empty vector (pPC86) | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Junc | Fos | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Rbd | E2F1 | +++ | − | + |

| MA | ||||

| YU2 | VAN-C | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| JR-CSF | VAN-C | − | +++ | − |

| NL4-3 | VAN-C | − | +++ | + |

| LAI | VAN-C | − | +++ | − |

| AD | VAN-C | − | +++ | − |

| p55 | ||||

| YU2 | VAN-C | − | +++ | − |

| LAI | VAN-C | − | +++ | − |

In each case, four independent cotransformants were tested for histidine and uracil prototrophy and for β-Gal activity. Each bait cDNA is fused to GAL4DBD (in plasmid pPC97), while the interactor is fused to GAL4TAD (in plasmid pPC86). The strength of interaction reported (−, no interaction; +, weak interaction [blue color visible after overnight incubation]; +++, strong interaction [blue color visible after 30 min] is not a quantitative measurement but rather a measure of extent of transcriptional activation of reporter genes as observed by eye.

Negative control.

Positive control.

Weak positive control.

Finally, we tested a number of matrix proteins from other HIV-1 clade B viruses for the ability to interact with VAN-C in the two-hybrid system. The matrix proteins from all strains tested interacted with VAN-C. Matrix from HIV-1YU2 and HIV-1NL4-3 showed the strongest interaction in the yeast two-hybrid screen, activating transcription from all three reporters; matrix from the other strains activated transcription from the highly specific URA3 reporter but not from the HIS3 or lacZ reporter (Table 1). Therefore, there appears to be some strain-specific variability in the strength of the VAN-C–MA interaction. The source of this variability is unknown. It is important to note that this two-hybrid variability does not necessarily mean a reduced in vivo affinity, as even viral strains whose matrix proteins interact weakly with VAN in the two-hybrid system package the protein efficiently into the virion (see below).

VAN binds GST-MA in vitro.

To confirm the matrix-VAN protein-protein interaction, we used in vitro binding assays with a bacterially expressed GST-MA fusion protein and a smaller C terminal segment of VAN tagged with His6 (VAN-C′ [Fig. 2]). Bacterial lysates containing GST alone or GST-MA were tested in a GST pull-down assay. While VAN-C′ binding to GST-MA was stable to 500 mM NaCl, GST alone bound very weakly to VAN-C′ and only at lower salt concentrations (Fig. 1b), confirming that HIV-1 matrix binds VAN in vitro.

Sequence features and homologs of hVAN.

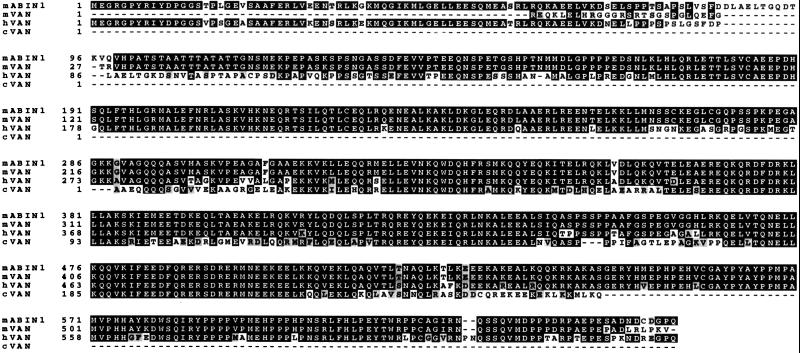

Sequence analysis of the putative hVAN ORF revealed a protein enriched in acidic amino acid residues (12% glutamic acid), with four putative leucine zippers, and several predicted regions of extensive coiled-coil structure (∼45% of the VAN ORF [Fig. 2]) indicative of a protein-protein interaction motif. A search of public genomic sequence databases showed that the VAN gene is located on chromosome 5q31-q33 (58). Further BLAST searches (1) with full-length human sequences identified partial mouse and chicken homologs (>70% amino acid sequence identity) to hVAN (Fig. 3), suggesting evolutionary conservation across the three species.

FIG. 3.

Amino acid sequence of hVAN aligned with the mouse ABIN1 (mABIN1), partial mouse (mVAN), and chicken (cVAN) sequences. Residues highlighted in black show identity; residues highlighted in gray show similarity. GenBank accession numbers: hVAN (previously described as Naf1α), AJ011896; mouse cDNA, AAO61107; mouse ABIN1, AJ24778; chicken proto-Ets, M23688.

Expression of VAN in mammalian tissues.

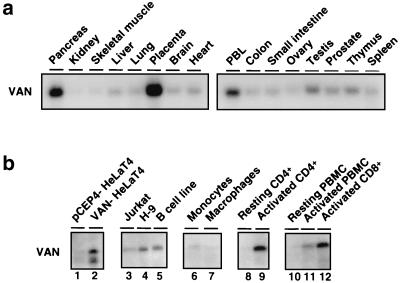

VAN mRNA was present as a single, fairly abundant 3.1-kb band in Northern blot analysis with poly(A)+ RNAs derived from a variety of human tissues (Fig. 4a). VAN protein expression was also examined in a number of cell lines and primary cells, as well as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), by immunoblot analysis with anti-hVAN antibody. While resting T cells expressed low amounts of VAN, activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and T-cell lines (Jurkat and H-9) showed high levels of VAN expression. However, primary monocytes and in vitro-derived monocyte-differentiated macrophages showed only low levels of protein expression similar to those seen in HeLa (cervical carcinoma) and HEK293 cells (Fig. 4b). Immunoblot analysis of protein expression in a number of mouse tissues using anti-hVAN antibody also showed a ∼70-kDa band, which was abundant in heart and skeletal muscle and expressed at lower levels in thymus, liver, kidney, brain, and intestinal tract (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

VAN expression. (a) VAN mRNA expression in several human tissues, determined by Northern blot analysis of polyadenylated RNA from human tissues using a probe specific for VAN mRNA. The size of the VAN transcript is 3.1 kb. (b) Expression of VAN protein in human cell lines and primary cells. Cell lysates from 1 million cells were analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-VAN antibody. Lane 1, HeLa T4 cells transfected with pCEP4 (empty vector); lane 2, HeLa T4 cells transfected with VAN; lane 3, Jurkat (CD4+ T-cell line); lane 4, H-9 (CD4+ T-cell line); lane 5, Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B-cell line; lane 6, monocytes; lane 7, monocytes differentiated into macrophages in vitro; lane 8, resting CD4+ T cells; lane 9, PHA-activated CD4+ T cells; lane 10, resting PBMC; lane 11, activated PBMC; lane 12, activated CD8+ T cells.

Localization of VAN.

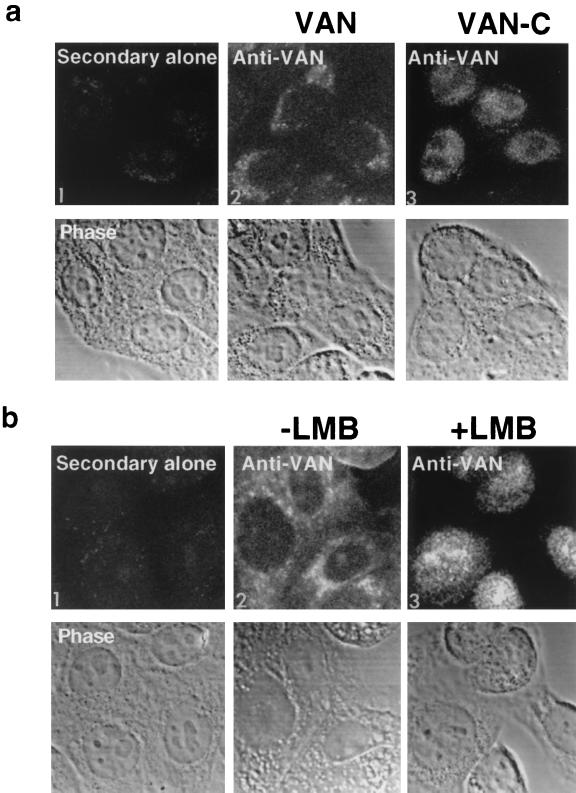

To determine VAN's intracellular location, we examined HeLa cells overexpressing full-length VAN by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-hVAN antibody. The cells showed punctate, predominantly cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 5a, image 2). VAN did not colocalize with markers for endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi bodies, mitochondria, actin, or microtubules (data not shown). Untransfected cells showed a similar staining pattern, though the intensity of the signal was fainter. In contrast to the full-length cytoplasmic protein, overexpressed VAN-C was localized primarily in the nucleus (Fig. 5a, image 3).

FIG. 5.

Intracellular localization of VAN. (a) HeLa cells overexpressing VAN or VAN-C. HeLa cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with an anti-VAN antibody or with secondary antibody alone, as indicated. The lower row shows the phase image corresponding to each labeled image in the top row. 1, HeLa T4 cells; 2, HeLa T4 cells transfected with VAN; 3, HeLa T4 cells transfected with VAN-C. (b) HeLa cells treated with LMB. HeLa cells were incubated with 5 nM LMB for 6 h prior to fixation and staining. The top row shows cells stained with anti-VAN; the bottom row shows the corresponding phase images. Similar results were obtained when cells were treated with different concentrations of LMB (10 nM, 100 nM, and 1 μM) for 2 h (data not shown). (c) VAN is localized to the nucleus of vaccinia virus-Gag-infected HeLa cells. HeLa cells were infected with vaccinia virus encoding HIV-1 Pr55Gag, matrix, CA, or β-Gal. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-VAN, anti-HIV-1 (anti-HIV IgIV), and anti-β-Gal antisera. VAN staining is shown in red; Gag staining is shown in green. Arrows indicate cells in which VAN and Gag are both nuclear localized. The white arrows track one cell across the panel, while the yellow arrows point to a second cell. No detectable background staining was observed with secondary antibody alone (data not shown).

Consistent with its nuclear localization, the C terminus of VAN has a putative monopartite NLS (14, 30), also found in the full-length, nucleus-excluded VAN (Fig. 2). This suggests that in the full-length protein the NLS is either masked or dominated by a competing cytoplasmic retention or nuclear export signal (NES).

VAN shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm in a Crm1-dependent manner.

Given the distinct localization of full-length VAN to the cytoplasm and the VAN-C to the nucleus, it is possible that the protein shuttles between the two compartments. The large size of VAN (72 kDa) precludes passive diffusion across the nuclear membrane. The directionality of movement across the nuclear pore depends on the direct or adapter-mediated association between a specific signal on a substrate protein and its receptor on one side of the pore and dissociation on the other side (44). Sequence analysis of VAN revealed four putative leucine-rich NESs (19, 31, 62) distributed throughout the VAN sequence (Fig. 2) that might explain the full-length protein's cytoplasmic localization. NESs of this type are recognized by the protein Crm1/exportin 1 (20, 45). Nuclear export is mediated by complex formation between an NES-containing protein, Crm1, and Ran-GTP. LMB blocks formation of this trimeric complex, preventing nuclear egress of NES-containing proteins and trapping the proteins in the nucleus (65). To determine whether VAN export is Crm1 dependent, we treated HeLa cells with LMB prior to fixation (58) and then examined the localization of endogenous VAN by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-hVAN antibody. While VAN was predominantly cytoplasmic in untreated cells (Fig. 5b, image 2), it was dramatically relocalized to the nucleus in cells treated with LMB (Fig. 5b, image 3). These data suggest that VAN shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in a Crm1-dependent manner. However, when wild-type (untagged) VAN was overexpressed, it did not relocalize to the nucleus in response to LMB treatment but tended to form discrete cytoplasmic aggregates (data not shown), indicating that some factor involved in nuclear localization of VAN may be limiting.

To test the function of the four putative NESs, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of conserved hydrophobic residues at positions 1 and 3 of each putative NES, replacing them with alanines (Fig. 2). A similar mutagenesis strategy had been previously shown to be sufficient for abrogating NES function (26, 62). Mutagenesis of the putative NESs independently, in pairs, or all together had little or no effect, as the NES-containing VAN mutants retained their cytoplasmic localization. This raises the possibility that the VAN gene may not encode a conventional leucine-rich NES, or it may shuttle in concert with another NES-bearing protein.

Relocalization of VAN in cells overexpressing HIV-1 Gag.

The shuttling properties of and interaction in vitro between VAN and matrix suggested that the two properties might colocalize intracellularly. To test this hypothesis, we infected HeLa T4 cells with vaccinia virus Gag and examined the infected cells overexpressing HIV-1 Gag by indirect immunofluorescence using antibodies to VAN (endogenous) and Gag (vaccinia virus expressed). While Pr55Gag showed a diffuse cytoplasmic staining pattern with some membrane staining, matrix was localized primarily to the plasma membrane. However, in a fraction of cells, both Pr55Gag (25 to 30% of cells) and matrix (5 to 10% of cells) were localized in the nucleus. Interestingly, the VAN signal paralleled the Gag signal; VAN was predominantly cytoplasmic, with some signal in the nucleus in cells in which Gag was cytoplasmic or membrane associated, but it localized to the nucleus of those cells in which Gag was nuclear (Fig. 5c). By contrast, VAN's cytoplasmic localization was unaffected in cells infected with vaccinia virus expressing HIV-1 CA or β-Gal, attesting to the specificity of VAN relocalization for Pr55Gag and matrix. These data independently validate VAN's ability to transit to the nucleus and provide further evidence for in vivo Gag-VAN association.

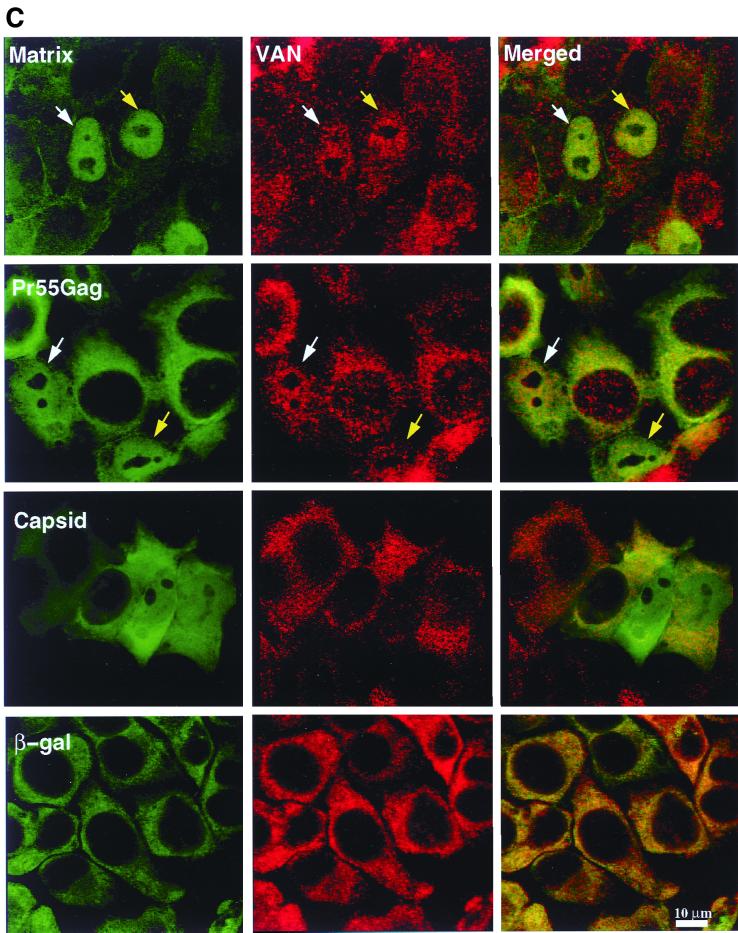

VAN is incorporated into HIV virions.

We investigated whether the matrix-VAN interaction was strong enough to allow VAN incorporation into virions. This cannot be determined by directly examining the virion preparations since they can include contaminating proteins that are present in microvesicles, which copurify with virions, or may include proteins that nonspecifically adhere to the surface of the virus. To measure virion incorporation, we performed a protease protection assay (47) on virus particles produced from chronically HIV-1MN-infected H-9 cell lines (4). Proteins outside the virion are digested by subtilisin, a nonspecific protease, while intravirion proteins are shielded from digestion by the viral membrane. Previously, such protease treatment was shown to eliminate >95% of contaminating nonviral cellular debris including microvesicles (45–47). The preparations were then either mock or subtilisin digested and centrifuged through a 20% sucrose cushion to separate virions from proteolyzed debris. Mock- and subtilisin-treated virus preparations were then analyzed by immunoblotting for the presence of the extracellular domain of the envelope protein (gp41), matrix, and VAN. The extracellular domain of gp41 was degraded by subtilisin, while matrix and VAN were subtilisin resistant, as expected. Proteins outside the virion were removed, while those inside the viral membrane were protected (Fig. 6a). VAN was readily detectable in the lanes containing mock- and protease-digested HIV-1MN samples in this and repeat experiments. The VAN signal in the protease-digested lane was somewhat less intense than that in the mock-digested lane, which indicated that some of the VAN associated with virions was removed by subtilisin and therefore may have been present outside the virion. Since the H-9 microvesicle sample showed little signal in the VAN blot (Fig. 6a), it is most likely that the VAN removed by digestion had simply adhered to the exterior of the virions. Similar data were obtained using a Nef deletion variant of HIV-1MN (Fig. 6a) as well as wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 (data not shown). Together, these results show that the majority of VAN in virion preparations is inside the virion. Interestingly, the ratio of VAN to matrix appears somewhat higher in the wild-type virus preparation than in the Nef deletion mutant. Thus, while Nef is not required for incorporation, it may increase the efficiency of incorporation of VAN. Using semiquantitative immunoblotting analysis with a full-length VAN fusion protein standard, we estimate that there are ∼80 molecules of VAN per wild-type HIV-1MN virion after subtilisin treatment (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

(a) VAN is incorporated into HIV-1 virions. HIV-1 virions produced from two chronically HIV-1MN-infected H-9 cell lines were concentrated by centrifugation through two consecutive sucrose density gradients. The virus-containing pellets were resuspended, and approximately 8 × 109 virions, as estimated by p24 ELISA, were either mock treated [(M)] or treated with subtilisin, a nonspecific, lipid-impervious protease [(S)]. The purified viral pellets were then resuspended in PBS and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies to VAN, matrix, and the extracellular domain of gp41 (lanes 3 and 4). Positions of molecular weight markers are shown on the left; the antibody used is shown on the right. Microvesicles derived from mock-infected cells are shown as controls (lanes 5 and 6). Similar data were obtained from Nef-deleted HIV-1MN (lanes 1 and 2) as well as wild-type (wt) HIV-1NL4-3 (data not shown). (b) Purification profile of virions over a Sephacryl S-1000 column. Virions produced from 293T cells cotransfected with VAN-C and an infectious proviral HIV-1AD clone were concentrated by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. The concentrated virus was resuspended in PBS and run over a Sephacryl S-1000 size exclusion column. The fractions were harvested and analyzed for amount of p24 present in each fraction. (c) Immunoblot analysis of HIV-1-transfected cells. The cell lysates and supernatant fractions obtained from 293T cells transfected with VAN-C and proviral DNA (pHIV-1AD) were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the presence of matrix and VAN-C. 1 to 13 denote the virus-containing fractions as they came off the column. (d) Immunoblot analysis of mock-transfected cells. Lysates and supernatant fractions from 293T cells cotransfected with VAN-C and empty vector were treated as described for panels a and b. Similar results were observed using HIV-1NL4-3 (data not shown).

Considering that HIV-1 buds from the plasma membrane, some host cytoplasmic proteins may be incorporated nonspecifically into newly budding virions. To address the issue of specificity of VAN incorporation, we examined whether the nucleus-localized VAN-C, also shown to interact with matrix in vitro, is incorporated into HIV virions. Virions produced from 293T cells cotransfected with VAN-C and an infectious HIV-1AD proviral clone were concentrated by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion, resuspended, and fractionated over a Sephacryl S-1000 size exclusion column before immunoblotting. The p24 (CA) levels peaked in fractions 4 and 5 (Fig. 6b) as previously reported (9). VAN-C cofractionated with HIV matrix and CA (Fig. 6c). As a control for microvesicle contamination, equal amounts of supernatants obtained from mock-transfected (transfected with vector lacking HIV-1 proviral DNA insert) cells were analyzed in a similar manner. In the supernatants from mock-transfected cells, a very faint band corresponding to VAN-C was observed after a much longer (15-min rather than 1-min) exposure (Fig. 6d). The intensity of this band is far too weak to account for the signal from the HIV-1 virions, indicating specific VAN-C–virion association. Similar results were obtained using HIV-1NL4-3 (data not shown).

A band of faster mobility that reacted with the hVAN antibody was also observed in virions but not in control supernatants from mock-transfected cell lines (Fig. 6c and d). A similar band was also seen in virus derived from chronically infected H-9 cells (Fig. 6a). This is probably an HIV-1 protease-mediated cleavage product of VAN or VAN-C, further suggesting that VAN or VAN-C is inside HIV-1 virions, as protease is known to cleave nonviral proteins incorporated into the virus particle (48, 66).

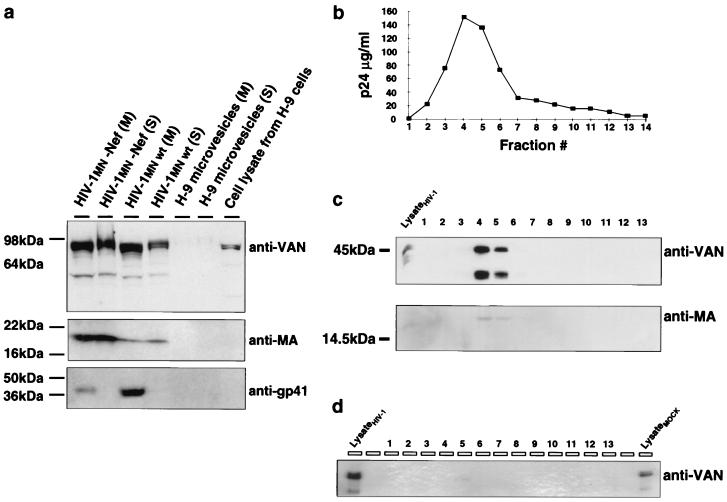

VAN overexpression inhibits viral replication.

Since we found that VAN interacts with matrix in vitro and is packaged into HIV-1 virions in vivo, it seemed likely that perturbing cellular VAN expression levels could affect viral replication. We engineered HeLa T4 populations to overexpress either full-length VAN or VAN-C. Whereas virion association of VAN suggests a positive role for VAN in the viral life cycle, we observed a paradoxical inhibition of replication in cells overexpressing VAN (11-fold) and VAN-C (2-fold) compared to control mock-transfected cell populations (Fig. 7a). This experiment was repeated multiple times using HIV-1NL4-3 as well as HIV-1LAI, and with independently derived VAN- and VAN-C-overexpressing HeLa T4 populations, with comparable results. Given the fact that HIV-1 replicates very efficiently in activated T cells, which have high levels of VAN (Fig. 3b), it is unlikely that VAN is inhibitory to the virus at physiologically relevant concentrations. However, this inhibition provides further evidence for in vivo interaction between Gag and VAN.

FIG. 7.

Overexpression of VAN in HeLa T4 cells inhibits HIV-1 replication. (a) HIV-1 growth curve in HeLa T4 cells. HeLa T4 cells were either mock transfected or transfected with full-length VAN or VAN-C. The cell lines thus derived were then infected with HIV-1. Supernatants were sampled for p24 production over a course of 6 days. Viral replication is impaired in cells transfected with VAN (circles) and VAN-C (triangles) compared with mock-transfected cells (squares). Each time point represents the mean of three independent infections, and error bars show standard deviations. Similar results were obtained using HIV-1NL4-3. (b) HeLa T4 cell lysates from mock (pCEP4)-transfected (M) and VAN-transfected cells. Numbers above the lanes indicate fold dilutions of cell lysates from VAN overexpressors.

DISCUSSION

Matrix-VAN interactions.

A two-hybrid screen identified VAN, a novel matrix-interacting protein. VAN interacts with both matrix and Pr55Gag precursor polyprotein when they are expressed as heterologous fusion proteins in yeast (Fig. 1a; Table 1). The specificity of this interaction is corroborated by a GST pull-down assay (Fig. 1b). Moreover, VAN-matrix interaction likely occurs in vivo, based on incorporation of VAN into HIV-1 virions (Fig. 6a), indirect immunofluorescence studies showing Gag-dependent VAN relocalization (Fig. 5c), and inhibition of viral replication in cells overexpressing VAN (Fig. 7a).

VAN is an evolutionarily conserved protein expressed in most human and mouse tissues tested. The matrix interaction site is further mapped to the C-terminus of VAN, since two different N-terminal truncations retained specific matrix interaction (Fig. 1).

VAN was previously described as a putative Nef-interacting protein identified by a two-hybrid screen (27). The Nef-interacting protein cDNA was reported to encode two isoforms, Naf1α and Naf1β, presumably generated by alternative splicing. The Naf1α cDNA sequence is identical to that of the VAN cDNA, raising the possibility that Nef could mediate the virion association of VAN. However, we were unable to detect a VAN-C–Nef interaction by two-hybrid analysis using our prey plasmid (Fig. 1a). Since the Naf1 prey cDNA isolated by Fukushi et al. (27) corresponds to an internal segment of the VAN ORF (amino acids 94 to 412) overlapping with VAN-C, the matrix-interacting domain of VAN may be distinct from the Nef-interacting domain. Additionally, since VAN is incorporated into Nef-deleted virions (Fig. 6a), and since VAN-C, which interacts with matrix but not with Nef (Fig. 1), is also packaged into viral particles (Fig. 6b), we conclude that virion incorporation of VAN does not require Nef. However, this does not preclude some other biological role for a Nef-VAN or a Nef-VAN-matrix interaction.

Additionally, overexpressing VAN significantly inhibited viral replication in HeLa T4 cells (Fig. 7a). In cells overexpressing matrix or Pr55Gag, VAN relocalizes to the nucleus (Fig. 4c). A plausible explanation for the observed inhibition is that increased complex formation between Pr55Gag and overexpressed VAN in HIV-infected cells causes some Gag to be relocalized to the nucleus or sequestered in the cytoplasm. Such aberrant sequestration could lead to degradation of these mislocalized Gag-VAN complexes, resulting in decreased intracellular levels of Pr55Gag, which would exert a negative effect on particle formation and lower p24 levels observed in Fig. 7a. In support of this hypothesis, we have data (not shown) indicating lower levels of intracellular Gag in producer cells overexpressing VAN. Given the fact that HIV-1 replicates very efficiently in activated T cells, which have high levels of VAN (Fig. 4b), it is unlikely that VAN is inhibitory to the virus at physiologically relevant concentrations of both proteins. However, this inhibition provides further evidence for in vivo interaction between Gag and VAN.

Cellular localization.

We performed indirect immunofluorescence studies to gain insight into possible functions of VAN. Both native and overexpressed full-length VAN (tagged and untagged) are predominantly cytoplasmic, while VAN-C is nuclear (Fig. 5b, image 2). However, a dramatic shift of endogenous VAN to the nucleus was noted in cells treated with LMB (Fig. 5b, image 3). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that VAN shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in a Crm1-dependent manner, confirming the presence of a functional NES associated with VAN.

Sequence analysis of VAN revealed a putative NLS in the C terminus and four putative NESs distributed throughout the protein (Fig. 2) that may direct its subcellular localization. Mutating all four NESs in a hemagglutinin fusion peptide-tagged VAN construct had no effect on subcellular localization of the protein. Moreover, when wild-type (untagged) VAN was overexpressed, it did not relocalize to the nucleus in response to LMB and tended to form discrete cytoplasmic aggregates (data not shown). These results could be explained by one of the following: (i) there is aggregation of overexpressed untagged VAN; (ii) tagging of VAN mutants with a fusion peptide from hemagglutinin can affect intracellular localization; (iii) VAN may have an unpredicted, cryptic, or exotic NES; or (iv) VAN may not have its own functional NLS but rather piggybacks into the nucleus on another NLS-containing protein that is present in limited amounts. This is critical, as in our assay for abrogation of NES function, nuclear localization of VAN is essential. In the absence of appropriate nuclear localization, we would not expect to see a difference between the wild-type and mutant NES-containing proteins. In support of this chaperone hypothesis, we observed that LMB has no effect on the cytoplasmic localization of overexpressed VAN, suggesting that a component involved in nuclear localization of VAN may be the limiting factor. Since overexpression of the mouse homolog of VAN (ABIN) inhibits NFκB activation (35), candidates for this VAN chaperone protein could include shuttling proteins in the NFκB pathway such as NFκB (32) and IκB (37).

Role in the HIV life cycle.

While VAN's cellular functions await further characterization, its interaction with HIV-1 Gag suggests important functions as a host factor involved in the HIV-1 life cycle. HIV-1's primary target cells, such as resting CD4+ T cells and macrophages, have low levels of VAN. To compensate for the absence of VAN in target cells, the virus encapsidates VAN when it buds from activated T cells, expressing high levels of the protein. This suggests that VAN may play an important role for HIV-1, possibly in the very early stages of infection establishment in those host cells with very low endogenous levels of VAN. The estimate of ∼80 molecules of VAN per virion closely approximates the number of matrix molecules calculated to be associated with the PIC (29). These results are consistent with a role for VAN early in the viral life cycle.

Based on VAN's interaction with the Gag gene products, its specific virion incorporation (Fig. 1 and 6a), and its Gag-dependent nuclear localization (Fig. 5c), we propose a model (Fig. 8) where one of VAN's functions as a nuclear shuttling host factor is to facilitate the nuclear import and retention of the viral PIC. Matrix has been shown to have both a functional NLS and nuclear export activity despite a lack of reported NESs (16). Furthermore, matrix mutants (MAΔ1-33, MAΔ87-132, and MAK18A/R22G) localize to the nucleus (16). We identified two putative NESs in matrix, MA13-22 and MA85-95, within the mutated regions (Fig. 2). Masking of NLSs has been reported as a regulatory mechanism of nucleocytoplasmic transport of signaling proteins and transcription factors such as NFκB (34, 43). An intriguing possibility is that VAN bound to intravirion matrix masks an NES within matrix itself, allowing matrix's nuclear import signals to dominate at the time of viral entry, defining the matrix molecules destined for nuclear retention. Such NES repression might be used as a general regulatory mechanism of intracellular localization of proteins containing both NLS and NES activities. Further experiments are required to test the binding of VAN to the NES-containing MA mutants to confirm the NES masking hypothesis and to elucidate the identity of VAN's cellular nuclear-cytoplasmic chaperone.

FIG. 8.

Relevance of the Gag-VAN interaction in the HIV-1 life cycle. The viral life cycle (black arrows) begins with attachment of the virus particle to cell surface receptors and ends with assembly and release of infectious retroviral particles from the cell. VAN (yellow) shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. However, at steady-state, VAN is localized predominantly in the cytoplasm. In a target cell the virus imports VAN, presumably by an interaction between VAN and Pr55Gag (carat) in the producer cell. VAN interacts with matrix (green circle) early in the viral life cycle, possibly facilitating nuclear targeting of matrix in association with the PIC and, by extension, nuclear import and retention of the HIV-1 PIC. Late in the viral life cycle at the time of assembly, as a Pr55Gag interactor, VAN may also play a role in exporting the newly synthesized unspliced genomic HIV-1 RNA (purple) and/or the nucleus-trapped Pr55Gag from the nucleus.

In addition to its function in nuclear import and retention of the PIC, VAN may also play a role late in the viral life cycle during virion production in the nuclear export of Pr55Gag and/or unspliced viral RNA; direct binding of VAN to RNA seems unlikely given VAN's acidic nature. These two functions need not be mutually exclusive. The model shown in Fig. 8 is consistent with the data and can be tested once cell lines that lack VAN or in which the matrix-VAN interaction is abrogated are generated. Further dissection of the matrix-VAN interaction will not only shed light on the cellular mechanisms of regulation of nuclear-cytoplasmic transport but also help to elucidate the HIV-1 life cycle. If VAN is indeed essential for HIV-1 replication, it would present a novel target for rational antiviral drug design.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following for generous advice and technical help: Michael Delannoy, confocal microscopy; Marc Vidal, two-hybrid screen; Diana Camaur, virion association experiments; Rick Bushman, in whose laboratory the VAN-C virion association experiments were performed; Keith Peden and Beatrice Hahn, proviral DNAs and cell lines; Joshua La Baer, Alala2 cDNA library; Barbara Wolff-Winiski, LMB; Larry Arthur, Julian Bess, and Mike Grimes, concentrated virus; Don Johnson, amino acid analysis; David Ford, virus concentration; and David E. Symer and Purnima Bhanot, critical reading of the manuscript. All experiments were performed in the laboratories of Jef D. Boeke and Robert F. Siliciano, who comentored Kalpana Gupta during her doctoral training.

This project was supported in part by federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, NIH, under contract NO1-CO-56000 (D.O.) and by NIAID grants P01-AI41215 (J.D.B.) and A128108 (R.F.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Smith J A, Seidman J G, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bess J W, Jr, Gorelick R J, Bosche W J, Henderson L E, Arthur L O. Microvesicles are a source of contaminating cellular proteins found in purified HIV-1 preparations. Virology. 1997;230:134–144. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bess J W, Jr, Powell P J, Issaq H J, Schumack L J, Grimes M K, Henderson L E, Arthur L O. Tightly bound zinc in human immunodeficiency virus type 1, human T-cell leukemia virus type I, and other retroviruses. J Virol. 1992;66:840–847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.840-847.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breeden L, Nasmyth K. Regulation of the yeast HO gene. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:643–650. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bugelski P J, Maleeff B E, Klinkner A M, Ventre J, Hart T K. Ultrastructural evidence of an interaction between Env and Gag proteins during assembly of HIV type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:55–64. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukrinsky M I, Haggerty S, Dempsey M P, Sharova N, Adzhubel A, Spitz L, Lewis P, Goldfarb D, Emerman M, Stevenson M. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature. 1993;365:666–669. doi: 10.1038/365666a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukrinsky M I, Sharova N, McDonald T L, Pushkarskaya T, Tarpley W G, Stevenson M. Association of integrase, matrix, and reverse transcriptase antigens of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with viral nucleic acids following acute infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6125–6129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camaur D, Trono D. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif particle incorporation. J Virol. 1996;70:6106–6111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6106-6111.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakrabarti S, Brechling K, Moss B. Vaccinia virus expression vector: coexpression of beta-galactosidase provides visual screening of recombinant virus plaques. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3403–3409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chevray P M, Nathans D. Protein interaction cloning in yeast: identification of mammalian proteins that react with the leucine zipper of Jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5789–5793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun T W, Finzi D, Margolick J, Chadwick K, Schwartz D, Siliciano R F. In vivo fate of HIV-1-infected T cells: quantitative analysis of the transition to stable latency. Nat Med. 1995;1:1284–1290. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cimarelli A, Luban J. Translation elongation factor 1-alpha interacts specifically with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 1999;73:5388–5401. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5388-5401.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dingwall C, Laskey R A. Nuclear targeting sequences—a consensus? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:478–481. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90184-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorfman T, Mammano F, Haseltine W A, Gottlinger H G. Role of the matrix protein in the virion association of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1994;68:1689–1696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1689-1696.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupont S, Sharova N, DeHoratius C, Virbasius C M, Zhu X, Bukrinskaya A G, Stevenson M, Green M R. A novel nuclear export activity in HIV-1 matrix protein required for viral replication. Nature. 1999;402:681–685. doi: 10.1038/45272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Facke M, Janetzko A, Shoeman R L, Krausslich H G. A large deletion in the matrix domain of the human immunodeficiency virus gag gene redirects virus particle assembly from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1993;67:4972–4980. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4972-4980.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer U, Huber J, Boelens W C, Mattaj I W, Luhrmann R. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses an export pathway used by specific cellular RNAs. Cell. 1995;82:475–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj I W. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fouchier R A, Meyer B E, Simon J H, Fischer U, Malim M H. HIV-1 infection of non-dividing cells: evidence that the amino-terminal basic region of the viral matrix protein is important for Gag processing but not for post-entry nuclear import. EMBO J. 1997;16:4531–4539. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freed E O, Englund G, Maldarelli F, Martin M A. Phosphorylation of residue 131 of HIV-1 matrix is not required for macrophage infection. Cell. 1997;88:171–173. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81836-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freed E O, Englund G, Martin M A. Role of the basic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix in macrophage infection. J Virol. 1995;69:3949–3954. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3949-3954.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freed E O, Martin M A. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J Virol. 1996;70:341–351. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.341-351.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freundlich B, Avdalovic N. Use of gelatin/plasma coated flasks for isolating human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1983;62:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukuda M, Gotoh I, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Cytoplasmic localization of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase directed by its NH2-terminal, leucine-rich short amino acid sequence, which acts as a nuclear export signal. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20024–20028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukushi M, Dixon J, Kimura T, Tsurutani N, Dixon M J, Yamamoto N. Identification and cloning of a novel cellular protein Naf1, Nef-associated factor 1, that increases cell surface CD4 expression. FEBS Lett. 1999;442:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01631-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallay P, Hope T, Chin D, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells through the recognition of integrase by the importin/karyopherin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9825–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallay P, Swingler S, Aiken C, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells: C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation of the viral matrix protein is a key regulator. Cell. 1995;80:379–388. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Bustos J, Heitman J, Hall M N. Nuclear protein localization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1071:83–101. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(91)90013-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerace L. Nuclear export signals and the fast track to the cytoplasm. Cell. 1995;82:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harhaj E W, Sun S C. Regulation of RelA subcellular localization by a putative nuclear export signal and p50. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7088–7095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinzinger N K, Bukinsky M I, Haggerty S A, Ragland A M, Kewalramani V, Lee M A, Gendelman H E, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Henderson L E, Benveniste R E, Sowder R, Copeland T D, Schultz A M, Oroszlan S. Molecular characterization of gag proteins from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVMne) J Virol. 1988;62:2587–2595. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2587-2595.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henkel T, Zabel U, van Zee K, Muller J M, Fanning E, Baeuerle P A. Intramolecular masking of the nuclear location signal and dimerization domain in the precursor for the p50 NF-kappa B subunit. Cell. 1992;68:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90083-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heyninck K, De Valck D, Vanden Berghe W, Van Criekinge W, Contreras R, Fiers W, Haegeman G, Beyaert R. The zinc finger protein A20 inhibits TNF-induced NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression by interfering with an RIP- or TRAF2-mediated transactivation signal and directly binds to a novel NF-kappaB-inhibiting protein ABIN. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1471–1482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphries E H, Temin H M. Requirement for cell division for initiation of transcription of Rous sarcoma virus RNA. J Virol. 1974;14:531–546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.14.3.531-546.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson C, Van Antwerp D, Hope T J. An N-terminal nuclear export signal is required for the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 1999;18:6682–6693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiernan R E, Ono A, Englund G, Freed E O. Role of matrix in an early postentry step in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 life cycle. J Virol. 1998;72:4116–4126. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4116-4126.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kornbluth R S, Oh P S, Munis J R, Cleveland P H, Richman D D. Interferons and bacterial lipopolysaccharide protect macrophages from productive infection by human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1137–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lama J, Trono D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein interacts with cellular protein HO3. J Virol. 1998;72:1671–1676. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1671-1676.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis P F, Emerman M. Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994;68:510–516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.510-516.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moroianu J. Nuclear import and export: transport factors, mechanisms and regulation. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1999;9:89–106. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v9.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohno M, Fornerod M, Mattaj I W. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: the last 200 nanometers. Cell. 1998;92:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80926-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ossareh-Nazari B, Bachelerie F, Dargemont C. Evidence for a role of CRM1 in signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science. 1997;278:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ott D E, Coren L V, Johnson D G, Kane B P, Sowder II R C, Kim Y D, Fisher R J, Zhou X Z, Lu K P, Henderson L E. Actin-binding cellular proteins inside human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. 2000;266:42–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ott D E, Coren L V, Johnson D G, Sowder II R C, Arthur L O, Henderson L E. Analysis and localization of cyclophilin A found in the virions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 MN strain. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:1003–1006. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ott D E, Coren L V, Kane B P, Busch L K, Johnson D G, Sowder II R C, Chertova E N, Arthur L O, Henderson L E. Cytoskeletal proteins inside human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions. J Virol. 1996;70:7734–7743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7734-7743.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ott D E, Nigida S M, Jr, Henderson L E, Arthur L O. The majority of cells are superinfected in a cloned cell line that produces high levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strain MN. J Virol. 1995;69:2443–2450. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2443-2450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parent L J, Wilson C B, Resh M D, Wills J W. Evidence for a second function of the MA sequence in the Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein. J Virol. 1996;70:1016–1026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1016-1026.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peytavi R, Hong S S, Gay B, d'Angeac A D, Selig L, Benichou S, Benarous R, Boulanger P. HEED, the product of the human homolog of the murine eed gene, binds to the matrix protein of HIV-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1635–1645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reil H, Bukovsky A A, Gelderblom H R, Gottlinger H G. Efficient HIV-1 replication can occur in the absence of the viral matrix protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:2699–2708. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roe T, Reynolds T C, Yu G, Brown P O. Integration of murine leukemia virus DNA depends on mitosis. EMBO J. 1993;12:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rose M D, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in yeast genetics. A laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiestl R H, Gietz R D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith D E, Fisher P A. Identification, developmental regulation, and response to heat shock of two antigenically related forms of a major nuclear envelope protein in Drosophila embryos: application of an improved method for affinity purification of antibodies using polypeptides immobilized on nitrocellulose blots. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:20–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spearman P, Wang J J, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein domains essential to membrane binding and particle assembly. J Virol. 1994;68:3232–3242. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3232-3242.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taagepera S, McDonald D, Loeb J E, Whitaker L L, McElroy A K, Wang J Y, Hope T J. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of C-ABL tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7457–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vidal M, Brachmann R K, Fattaey A, Harlow E, Boeke J D. Reverse two-hybrid and one-hybrid systems to detect dissociation of protein-protein and DNA-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10315–10320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.von Schwedler U, Kornbluth R S, Trono D. The nuclear localization signal of the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 allows the establishment of infection in macrophages and quiescent T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6992–6996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watson D K, McWilliams M J, Papas T S. A unique amino-terminal sequence predicted for the chicken proto-ets protein. Virology. 1988;167:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wen W, Meinkoth J L, Tsien R Y, Taylor S S. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell. 1995;82:463–473. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westervelt P, Trowbridge D B, Epstein L G, Blumberg B M, Li Y, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Price R W, Ratner L. Macrophage tropism determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vivo. J Virol. 1992;66:2577–2582. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2577-2582.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson S A, Sieiro-Vazquez C, Edwards N J, Iourin O, Byles E D, Kotsopoulou E, Adamson C S, Kingsman S M, Kingsman A J, Martin-Rendon E. Cloning and characterization of hIF2, a human homologue of bacterial translation initiation factor 2, and its interaction with HIV-1 matrix. Biochem J. 1999;342:97–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolff B, Sanglier J J, Wang Y. Leptomycin B is an inhibitor of nuclear export: inhibition of nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Rev protein and Rev-dependent mRNA. Chem Biol. 1997;4:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Kim J, Seshaiah P, Natsoulis G, Boeke J D, Hahn B H, Kappes J C. Targeting foreign proteins to human immunodeficiency virus particles via fusion with Vpr and Vpx. J Virol. 1995;69:3389–3398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3389-3398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu X, Yuan X, Matsuda Z, Lee T H, Essex M. The matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is required for incorporation of viral envelope protein into mature virions. J Virol. 1992;66:4966–4971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4966-4971.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuan X, Yu X, Lee T H, Essex M. Mutations in the N-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block intracellular transport of the Gag precursor. J Virol. 1993;67:6387–6394. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6387-6394.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]