Abstract

The function of proteins depends on their correct structure and proper dynamics. Understanding the dynamics of target proteins facilitates drug design and development. However, dynamic information is often hidden in the spatial structure of proteins. It is important but difficult to identify the specific residues that play a decisive role in protein dynamics. Here, we report that a critical glycine residue (Gly463) dominates the motion of threonyl-tRNA synthetase (ThrRS) and the sensitivity of the enzyme to antibiotics. Obafluorin (OB), a natural antibiotic, is a novel covalent inhibitor of ThrRS. The binding of OB induces a large conformational change in ThrRS. Through five crystal structures, biochemical and biophysical analyses, and computational simulations, we found that Gly463 plays an important role in the dynamics of ThrRS. Mutating this flexible residue into more rigid residues did not damage the enzyme’s three-dimensional structure but significantly improved the thermal stability of the enzyme and suppressed its ability to change conformation. These mutations cause resistance of ThrRS to antibiotics that are conformationally selective, such as OB and borrelidin. This work not only elucidates the molecular mechanism of the self-resistance of OB-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens but also emphasizes the importance of backbone kinetics for aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-targeting drug development.

Subject terms: Computational biophysics, Mechanism of action, Enzymes

Crystal structures and molecular dynamics simulations reveal that a critical glycine residue dominates the motion of threonyl-tRNA synthetase and the sensitivity of the enzyme to conformation selective inhibitors.

Introduction

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) are key enzymes for protein translation in all cells, catalyzing the formation of an ester bond between a specific amino acid and the 3’-end adenosine of its conjugate tRNA1,2. There are three factors that make aaRSs valuable therapeutic targets. First, the sequence and fine structure differences between pathogenic microbial aaRS and human aaRS are applicable for designing drugs that selectively inhibit the pathogen aaRS3,4. Second, only low levels of aaRSs are required for protein translation under physiological conditions, and cells are able to withstand the down-regulation of aaRSs; therefore, drugs that specifically target hyperproliferative cells, such as cancer cells, may be developed5. Third, some aaRSs have nonclassical functions associated with specific pathologies or cancers, making them potential targets for the development of novel pharmacological approaches6–8.

AaRSs present multiple druggable pockets, including amino acid- and ATP-binding sites, tRNA-binding regions, and other binding sites, such as editing sites and auxiliary hydrophobic pockets9. Competitive binding to these sites with substrate molecules is a common mechanism of action (MoA) for aaRS inhibitors, including single-site10–15, dual-site16–20, and recently developed triple-site inhibitors21. In addition, inhibitors with novel MoAs, including Trojan horses22,23, induced-fit24, and reaction hijacking inhibitors25 have been reported. These inhibitors are highly valuable for understanding the catalytic mechanism of aaRS and for developing therapeutic drugs that target aaRS.

The natural product Obafluorin (OB) is a potent inhibitor of bacterial threonyl-tRNA synthetase (ThrRS)26. It is produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 39502 through the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) assembly line26–32. The NRPS ObiF contains a type I thioesterase (TE) domain with a rarely reported cysteine residue at the catalytic site that plays a critical role in the formation of the OB β-lactone ring29. OB has broad antibiotic activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens26,27. The catechol moiety of OB was found to be essential for its antibacterial activity33. Our previous work showed that OB covalently binds to ThrRS, forming an ester bond with a tyrosine residue in the catalytic center via the highly strained β-lactone ring34, making OB the first covalent aaRS inhibitor with demonstrated crystal structures.

The elucidation of the self-resistance mechanisms of antibiotic-producing microorganisms will help to reveal the MoA of antibiotics, guide the discovery of new natural products, and provide key clues for clinical antibiotic resistance. The resistance of P. fluorescens to OB is related to the expression of ObaO, a second copy of ThrRS26,33. However, why ObaO is resistant to OB remains unknown.

During the analysis of the reason for the resistance of ObaO to OB, we found that a glycine residue involved in the formation of the active pocket of ThrRS contributes to the latter’s sensitivity to OB. Through five crystal structures, biochemical and biophysical analyses, and computational simulations, we found that mutation of this flexible residue to a more rigid residue, such as a serine or an alanine, did not alter the structure, but significantly improved the thermal stability of the enzyme and suppressed the ability of ThrRS to change conformation. These mutations caused resistance of ThrRS to antibiotics that require conformational changes in ThrRS, including OB and another ThrRS inhibitor, borrelidin (BN). This work provides a deeper understanding of the MoA of OB and emphasizes the importance of backbone kinetics for drug development.

Results

Potential residues that cause OB resistance

ObaO, the second ThrRS in P. fluorescens, exhibits partial resistance to OB (Fig. 1a)26. Knockout of ObaO in P. fluorescens ATCC 39502 results in OB sensitivity, while expression of ObaO in OB-sensitive Escherichia coli strains confers resistance to OB26. However, the structure of ObaO predicted by Alphafold35 is very similar to that of E. coli ThrRS (EcThrRS, Fig. 1b). In particular, the residues that interact with l-Thr, ATP, and tRNA in EcThrRS and ObaO are 100% conserved36. The reason why ObaO is resistant to OB is interesting. This immune protein is not only found in P. fluorescens, but also in Chitiniphilus shinanonensis and Burkholderia diffusa, which can produce OB in vivo26 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the EcThrRS–OB complex structure, 18 residues in the active center of ThrRS are located within 4.5 Å of the OB34. Among these residues, only Ala316 is substituted by an asparagine residue in the P. fluorescens, C. shinanonensis, and B. diffusa ObaO proteins. However, this substitution of alanine by asparagine also occurs in the P. fluorescens, C. shinanonensis, and B. diffusa housekeeping ThrRS proteins (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 2). Using a thermal shift assay (TSA) and an ATP hydrolysis assay34, we tested whether mutating Ala316 to asparagine would create OB resistance. Compound 36j, a substrate-competitive ThrRS inhibitor, was used as an experimental control21 (Supplementary Fig. 3). We have shown that the influence of OB on the thermal stability of ThrRS (or ThrRS mutants) is greater than or close to 36j when OB forms a covalent bond with the enzyme, and much less than that of 36j when OB cannot form a covalent bond with the enzyme34. The TSA results showed that OB increased the mid-melting point (Tm) of EcThrRS_A316N by 33.4 °C, which is slightly greater than that of 36j (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Consistently, the ATP hydrolysis assay showed that OB had a strong inhibitory effect on EcThrRS_A316N with an IC50 value of 848 nM (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Thus, the resistance of ObaO to OB is not due to the substitution of residues directly interacting with OB.

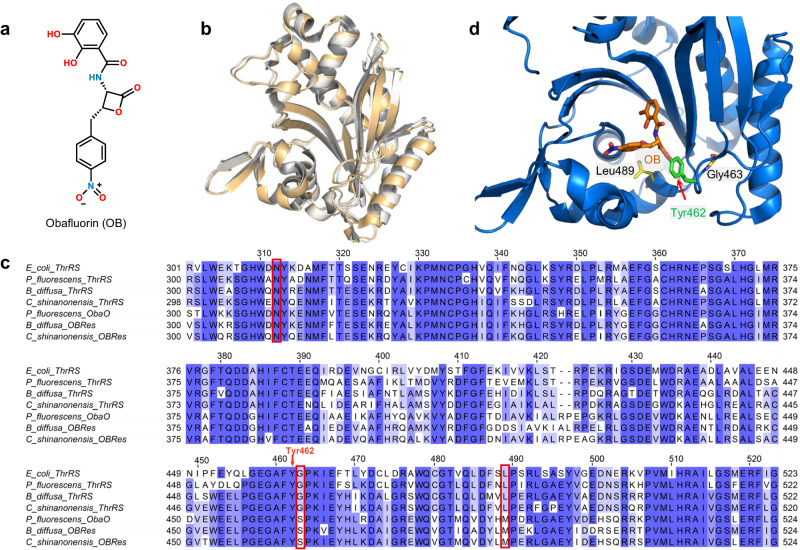

Fig. 1. Sequence alignment and structural analysis suggested that some residues may lead to OB resistance.

a Chemical structure of OB. b Superimposition of the structures of the catalytic domains of EcThrRS (gold, PDB code: 1EVK) and ObaO (white, predicted by AlphaFold). The RMSD is 0.740 Å over 280 Cα atoms. c Sequence alignment of ThrRS homologs. The alignment was performed by Clustal Omega and processed with Jalview. The alignment of Ala316, Gly463 and Leu489 corresponding to EcThrRS are highlighted in red boxes. d Zoomed-in view of the catalytic pocket (blue cartoon) of EcThrRS bound to OB (orange sticks). Tyr462 is shown as green sticks. Gly463 and Leu489 are shown as yellow sticks.

We therefore looked for the replacement of residues that might cause OB resistance in an expanded area in ObaO proteins. We noticed that Gly463 and Leu489 are two strictly conserved residues in the ThrRS proteins, but they are replaced by a serine and a methionine in the ObaOs, respectively (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 2). In particular, Gly463 is adjacent to Tyr462, which is the residue covalently bound to OB, and Leu489 is located within 7 Å of the OB in the pocket (Fig. 1d). We postulated that the substitution of these two residues might prevent the binding of ObaO to OB or hinder the formation of the covalent bond between ObaO and OB.

The glycine to serine substitution confers resistance of EcThrRS to OB

We expressed and purified the G463S and L489M EcThrRS mutants to examine the effect of these two residue substitutions on OB resistance. We utilized TSA to preliminarily estimate the binding affinities of EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_L489M to OB. The results showed that 36j and OB increased the Tm of EcThrRS_L489M by 22.7 °C and 22.6 °C, respectively (Fig. 2a), suggesting that OB strongly binds to EcThrRS_L489M, similar to 36j. In contrast, 36j increased the Tm of EcThrRS_G463S by 22.1 °C while OB increased the Tm of EcThrRS_G463S by only 13.3 °C (Fig. 2a), suggesting that the binding affinity between OB and EcThrRS_G463S is much weaker than that between 36j and EcThrRS_G463S. These results suggest that the G463S mutation weakens the binding affinity of ThrRS for OB, while the L489M mutation does not. Next, we studied the inhibitory activity of OB against EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_L489M in an ATP hydrolysis assay. OB had a strong inhibitory effect on EcThrRS_L489M, with an IC50 value of 215 nM (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the mutation of Leu489 to a methionine does not confer resistance of EcThrRS to OB. In contrast, OB showed poor activity against EcThrRS_G463S (Fig. 2b), with 5 μM OB inhibiting only approximately 10% of the activity of EcThrRS_G463S, indicating that mutating Gly463 to a serine renders EcThrRS resistant to OB.

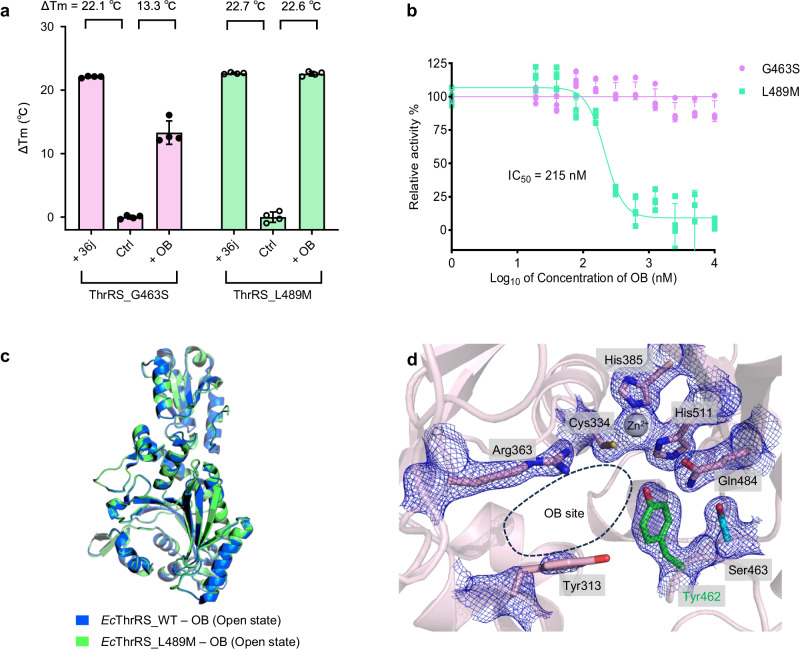

Fig. 2. Ser463 confers the resistance of OB to EcThrRS rather than Met489.

a Diagram of the ΔTm values of EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_L489M in the presence or absence of OB and 36j. Error bars represent the standard deviations (n = 4, mean value ± SD). All the data points are shown as small circles. b Inhibitory curves of OB on the ATP hydrolysis activity of EcThrRS_G463S or EcThrRS_L489M. Error bars represent the standard deviations (n = 4, mean value ± SD). All data points for EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_L489M are shown as pink and green dots, respectively. c Superimposition of the structures of EcThrRS_WT–OB (marine cartoons) and EcThrRS_L489M–OB (green cartoons). The RMSD is 0.160 Å over 385 Cα atoms. d Zoomed-in view of the catalytic pocket of EcThrRS_G463S, which was crystallized in the presence of OB. The 2Fo-Fc electron map (blue meshes contoured at 1.0 σ) is shown together with the structure model. The Tyr462 residue and Ser463 residue are shown as green and cyan sticks, respectively. The OB binding site is circled with black dashed lines. In this state, the OB cannot form a covalent bond with Tyr462; hence, no density for the OB can be seen. The density of Tyr313 is also poor in this state.

We confirmed this finding by crystallization experiments (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). An EcThrRS_L489M–OB complex structure was successfully obtained by cocrystallizing 300 μM EcThrRS_L489M protein with 600 μM OB (Supplementary Fig. 5). The conformation of EcThrRS_L489M was the same as that of the WT protein (PDB: 8H98) when both were in complex with OB (Fig. 2c). Because in the OB-binding conformation, the active pocket has a larger opening34, we refer to this state as the “open state”. The MoA of OB in EcThrRS_L489M remained consistent with what we found in EcThrRS_WT34. In short, the β-lactone ring of OB opens and forms an ester bond with Tyr462; the o-diphenol group forms coordination bonds with the ThrRS conserved Zn2+ ion; and the nitrobenzene group binds between Tyr313 and Arg363 (Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast, cocrystallizing 300 μM EcThrRS_G463S protein with 600 μM OB did not result in an EcThrRS_G463S–OB complex structure. No electron density of OB was observed in the catalytic pocket of EcThrRS_G463S under this condition (Fig. 2d). The active pocket of this structure has neither an OB nor substrate molecules, so it is in an “apo state”. The conformation in this state is similar to the “adenylation state” of the EcThrRS_Y462F–ATP complex structure we determined earlier34, but slightly wider (Supplementary Fig. 7). This structure also indicates that although G463S weakens ThrRS binding to OB, it does not disrupt the active conformation of ThrRS.

To further confirm that this glycine is the key residue involved in OB sensitivity, we studied the corresponding reverse mutation (S464G) of the OB resistance gene ObaO. Similarly, we utilized a thermal shift assay and an ATP hydrolysis assay to test whether ObaO_S464G lost resistance to OB. The TSA results showed that OB increased the Tm of ObaO_WT by 3.2 °C but increased the Tm of ObaO_S464G by 14.1 °C (Supplementary Fig. 8a), suggesting that the S464G mutation can bind to OB. Consistently, the ATP hydrolysis assay showed that OB had no inhibitory effect on ObaO_WT but inhibited the activity of ObaO_S464G, with an IC50 value of 3.9 μM (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Therefore, mutation of the corresponding serine to glycine restores the sensitivity of ObaO to OB.

Together, these results indicate that Gly463 is a key residue in ThrRS susceptibility to OB and that replacing it with a serine will induce OB resistance in ThrRS.

The OB resistance of ThrRS mutant is not because of spatial repulsion

In the EcThrRS_G463S structure, the hydroxyl group of Ser463 is 5.0 Å away from the phenolic hydroxyl group of Tyr462 (Fig. 3a), which attacks the lactone structure of OB and forms a covalent bond with it34. Thus, the sidechain of Ser463 is too short to clash with the presumably bound OB and it is also unlikely that Ser463 will directly affect the nucleophilicity of Tyr462 and prevent it from forming a covalent bond with OB.

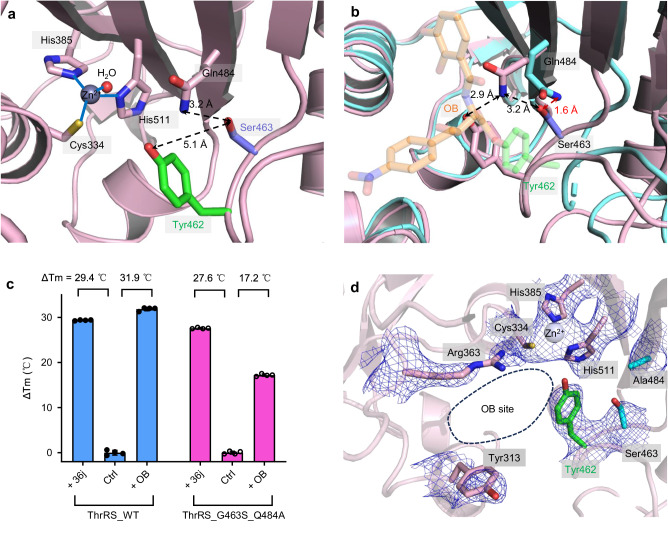

Fig. 3. Spatial interaction between Ser463 and Gln484 does not confer OB resistance.

a Zoomed-in view of the catalytic center of EcThrRS_G463S. Tyr462 is shown as green sticks, Ser463 is shown as slate sticks, and Gln484, Cys334, His385 and His511 are shown as pink sticks. b Superimposition of the structures of EcThrRS_G463S (pink cartoons) and EcThrRS_WT–OB (cyan cartoons). OB is shown as transparent orange sticks. c Diagram of the Tm values of EcThrRS_WT and EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A in the presence or absence of OB and 36j. Error bars represent the standard deviations (n = 4, mean value ± SD). All the data points are shown as small circles. d Zoomed-in view of the catalytic pocket of EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A which was crystallized in the presence of OB. The 2Fo-Fc electron map (blue meshes contoured at 0.8 σ) is shown together with the structure model. Tyr462 is shown as green sticks. Ser463 and Ala484 are shown as cyan sticks. The OB binding site is circled with black dashed lines. In this state, the OB cannot form a covalent bond with Tyr462; hence, no density for OB can be seen.

We then considered that Ser463 might have indirect effects through other OB-binding residues. In the apo state EcThrRS_G463S structure, the sidechain of the highly conserved residue Gln484 in the catalytic pocket forms a hydrogen bond with Tyr462, while in the OB-bound structure of the wild type (open state), the conformation of Gln484 is changed to accommodate OB (Fig. 3b). The distance between Ser463 and the conformation-altered Gln484 is only 1.6 Å (Fig. 3b). Therefore, if OB could induce a conformational change in Gln484 of EcThrRS_G463S, there might be repulsion between the two residues. To test the possibility that Ser463 might become resistant to OB by blocking the conformational change of Gln484, we designed a G463S_Q484A mutant to remove the sidechain of Gln484 to avoid potential spatial conflicts. We expected that the G463S_Q484A mutant would recover sensitivity to OB. However, in the TSA experiment, OB increased the Tm of EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A by 17.2 °C, 10 °C less than the effect of 36j (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A mutant, similar to EcThrRS_G463S, could still not be covalently inhibited by OB. Consistently, cocrystallizing 300 μM EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A protein with 600 μM OB did not yield an EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A–OB complex structure (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table 3). The EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A structure is still in an apo state.

Therefore, G463S endows ThrRS with resistance to OB neither by altering the protein’s structure nor by direct or indirect spatial repulsion.

The glycine substitution restricts the conformational change of the active pocket of ThrRS

In the catalytic cycle of an enzyme, the conformation of its active pocket normally exhibits a series of dynamic states. At the same time, we observed that the OB binding conformation of ThrRS is distinctly different from the apo or adenylation conformation34. Since glycine is the only nonchiral residue with the greatest flexibility, we further proposed that the G463S mutation might induce resistance to OB by altering the molecular dynamics (MD) of the protein. To investigate the role of Gly463 in the movement of the enzyme, we performed all-atom MD simulations of EcThrRS_WT and the EcThrRS_G463S mutant. Arg363 and Ala460 are two residues located on opposite sides of the OB binding pocket of ThrRS. The distance between their centroids (denoted as DR-A) can be used to characterize changes in the size of the pocket (Fig. 4a). In the MD simulation, the WT protein had two peaks in the frequency distribution curve, one corresponding to a DR-A of 13 Å and the other corresponding to a DR-A of 17 Å (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the EcThrRS_G463S mutant had only one peak at a DR-A of 14 Å (Fig. 4b). For reference, the DR-A is 17 Å when ThrRS binds OB and 12 Å when it binds ATP (Supplementary Fig. 9). This result suggests that the pocket of the WT protein has greater conformational variability and that the G463S replacement compresses its conformational distribution.

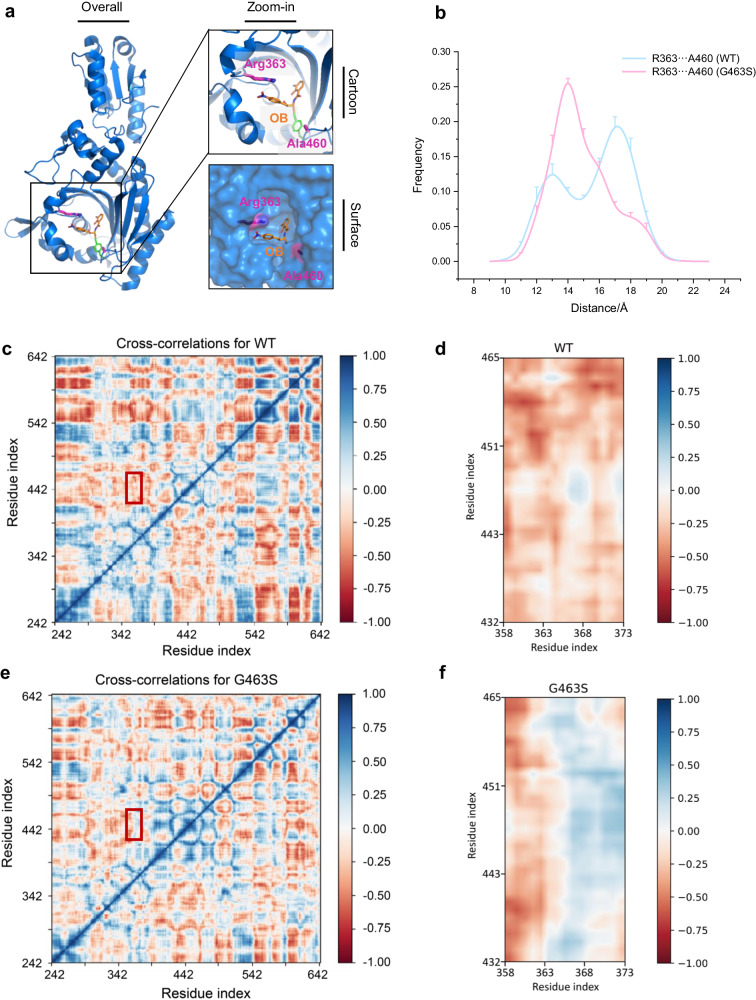

Fig. 4. The G463S mutation altered the dynamic properties of the active pocket.

a Arg363 and Ala460 are located on both sides of the inlet of the catalytic pocket where OB binds. These two residues are shown as magenta sticks. b The G463S mutation alters the distribution of the conformational states of the protein EcThrRS. The distance between the centers of mass of the residues Arg363 and Ala460 is defined as the width of the catalytic pocket. The conformational space shifts of WT and G463S are shown as cyan and pink curves, respectively. Eight sets of simulations with different random initial velocities were performed and data were collected from 9 to 23 Å per angstrom (n = 8, mean value ± SD). c, d Dynamic cross-correlation maps (DCCM) of EcThrRS_WT. The dynamic cross-correlation matrix of Cα atoms around their mean positions is calculated. The extent of correlated motions and anticorrelated motions are color-coded from blue to red, which represents positive and negative correlations, respectively. (d) is a magnified view of the region in the red box in (c). e, f DCCM of EcThrRS_G463S. (f) is a magnified view of the region in the red box in (e).

The dynamic characteristics of the pocket were also visualized using dynamic cross-correlation maps (DCCM)37, a method that quantifies the correlation of movements between pairs of residues within a protein over the course of MD simulations. Specifically, positive correlation values observed in DCCM indicate synchronized movements between residue pairs, moving in the same direction38, which usually reflects a structurally rigid interaction or coordination within the protein structure. Conversely, negative correlation values signify that the movements of residue pairs are opposite to each other, a phenomenon that often contributes to structural flexibility and dynamic interactions within the protein.

The N-terminal region of EcThrRS (residues 1–225) contains two domains involved in the proofreading of aminoacyl-tRNA (Supplementary Fig. 10). The constraints between this region and the catalytic domain (residues 242–535) or the anticodon-binding domain (residues 535–642) are weak. Therefore, the N-terminal region of EcThrRS was not included in our MD simulations. Residues 358–373 and residues 432–465 are from two opposite sides of the pocket (Supplementary Fig. 11). The motion of these two groups was negatively correlated in the MD trajectories of the WT protein, suggesting that the pocket of the WT protein is more dynamic (Fig. 4c, d). However, the motion of these two groups was positively correlated in the MD trajectories of the EcThrRS_G463S mutant, suggesting that the pocket of this mutant is relatively rigid (Fig. 4e, f).

These results suggest that the conformation of the active pocket of the WT protein is more flexible and can switch to a probable conformation to expose a larger binding pocket for the binding of OB, while the G463S mutation alters the conformational variability of the binding pocket of the protein and prevents the binding event (Supplementary Movie 1).

A small chiral residue substitution reproduces conformation limitation and OB resistance of ThrRS

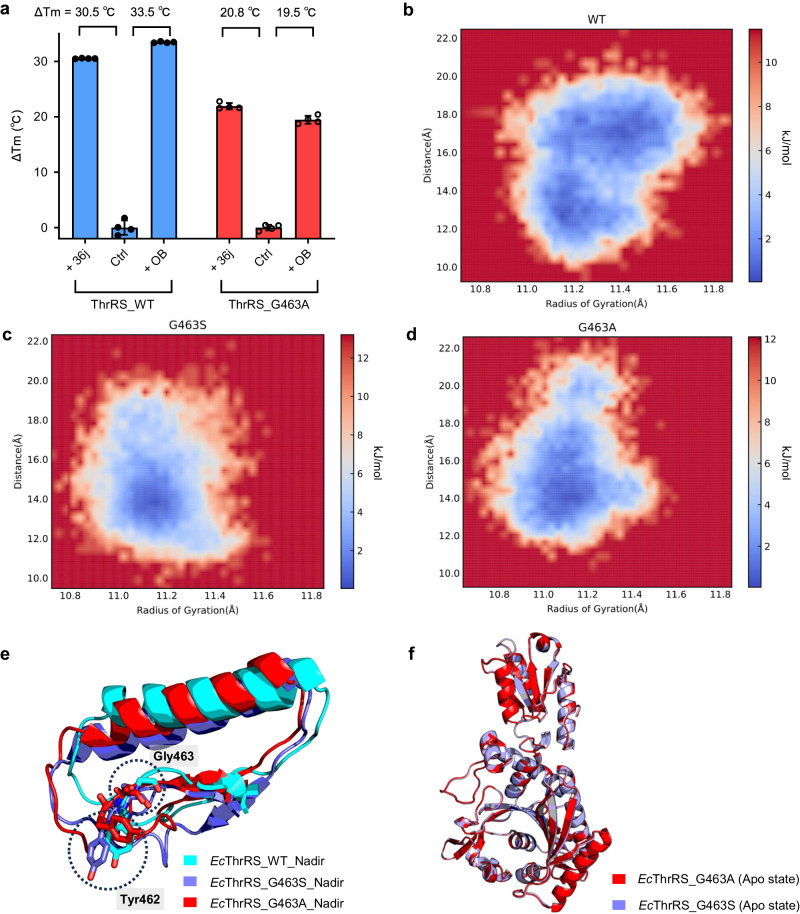

Based on the above study, we speculated that G463S made ThrRS OB resistant due to the loss of the flexibility of the glycine residue, rather than due to the property of the serine hydroxyl sidechain. To test this speculation, we constructed an EcThrRS_G463A mutant. The TSA experiments showed that OB increased the Tm of EcThrRS_G463A by 19.5 °C, which was 14.0 °C less than that of the WT and 1.3 °C less than the Tm of EcThrRS_G463A increased by 36j (Fig. 5a). In addition, ATP hydrolysis experiments showed that OB had no inhibitory effect on EcThrRS_G463A (Supplementary Fig. 12), indicating that EcThrRS_G463A is also resistant to OB.

Fig. 5. The G463A mutation generates similar effects on the conformational change of ThrRS and blockage on the covalent binding of OB which were observed in the mutant G463S.

a Diagram of the ΔTm values of EcThrRS_WT and EcThrRS_G463A in the presence or absence of OB and 36j. Error bars represent the standard deviations (n = 4, mean value ± SD). All the data points are shown as small circles. b–d Free energy contour maps derived from the radius of gyration (Rg) and RMSD values, where the dark blue area indicates a lower energetic conformation state. The Rg was calculated for residues 419–467. EcThrRS_WT exhibited a different free energy landscape (FEL) from those of both G463S and G463A, especially possessing a larger conformational tether of Rg. e Superimposition of the structure of residues 419-467 of EcThrRS_WT (cyan cartoons), G463S (slate cartoons) and G463A (red cartoons) at the FEL nadir corresponding to Fig. 5b–d. Residues at positions 462 and 463 are shown as sticks and circled with black dashed lines. f Superimposition of the structures of EcThrRS_G463A (red cartoons) and EcThrRS_G463S (slate cartoons). The RMSD is 0.343 Å over 318 Cα atoms.

We also analyzed the conformational motion of EcThrRS_G463A by MD simulation and used DR-A to represent the size of the pocket. The frequency curve of EcThrRS_G463A had only one peak at a DR-A of approximately 14 Å, which was close to and slightly larger than that of EcThrRS_G463S (Supplementary Fig. 13). This finding suggests that the pocket of EcThrRS_G463A cannot be extended so that its DR-A reaches 17 Å and can be effectively suppressed by OB.

To further decipher the difference in conformational space between WT and mutant ThrRSs, we performed free energy landscape (FEL) analysis and obtained representative structures with the most stable conformations from the simulation ensembles. EcThrRS_WT shows a different profile of FEL from either G463S or G463A. Compared to the free energy landscapes of EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_G463A, the energy basin of EcThrRS_WT covers a much larger range of radii of gyration (Rg), indicating that these conformations obtained along the trajectory experienced larger conformational changes (Fig. 5b-d). By comparing the conformation of residues 419-467 in the FEL nadir structure of the three proteins, we found that EcThrRS_WT had the most extended conformation, followed by G463A, and the narrowest was G463S (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, by comparing the FEL nadir conformation in the computational simulation and the real crystal structures, we found that the FEL nadir conformation of EcThrRS_WT was closer to the open state crystal structure, while the FEL nadir conformations of EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_G463A were more similar to the apo state crystal structures (Supplementary Fig. 14). These analyses suggest that the G463S and G463A mutations affect the conformational space of the ThrRS structure and cannot expose the active site for OB entry and reaction with Tyr462.

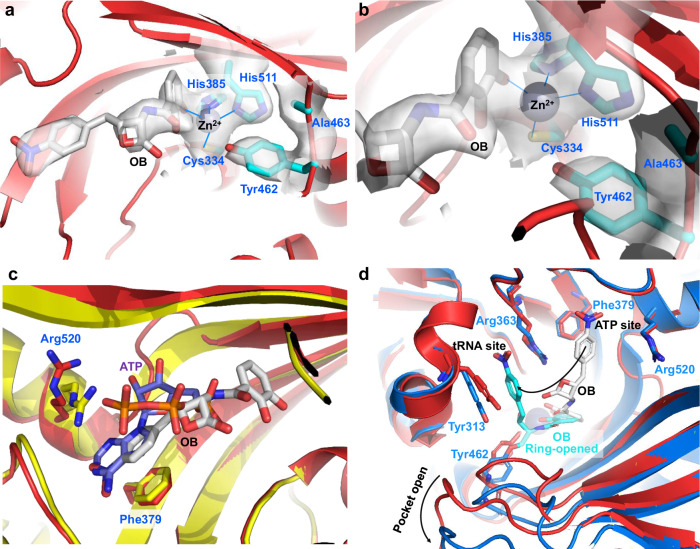

Similarly, we cocrystallized 300 μM EcThrRS_G463A with 600 μM OB and determined a 3.0 Å structure (Supplementary Table 4). As we predicted, the Tyr462 residue was not covalently modified by OB (Supplementary Fig. 15a) and the conformation of this structure was the same as that of EcThrRS_G463S (Fig. 5f). Most interestingly, there are some large but discontinuous electron densities near the ATP binding site as well as the zinc ion in this structure (Supplementary Fig. 15a). These electron densities can barely accommodate the OB structure (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 15b). We suspected that this is caused by unstable binding of OB in the ThrRS active pocket. In this case, one of the phenol hydroxyl groups forms a coordination bond with the zinc ion (Fig. 6b), and the nitrophenyl group inserts into the ATP binding site between Phe379 and Arg520 (Fig. 6c). This may be an intermediate state of OB binding in ThrRS. The conformation of the wild-type ThrRS can be further opened and the nitrobenzene portion of OB can instead bind to the tRNA binding site between Tyr313 and Arg363, thus bringing the lactone ring close to Tyr462 and reacting with it to form a new covalent bond (Fig. 6d, and Supplementary Movie 2). In contrast, the conformation of EcThrRS_G463A cannot be further opened, and in this binding mode, OB can be competed out by ATP (Supplementary Movie 3). Consistent with this assumption, when EcThrRS_G463A was cocrystallized in the presence of both OB and ATP, only ATP was resolved in the pocket (Supplementary Fig. 16, Supplementary Table 5). In summary, these results suggest that Gly463, which exploits the flexibility of a glycine residue, is a key site in determining the molecular dynamics of ThrRS.

Fig. 6. OB noncovalently binds to EcThrRS_G463A without inducing a conformational change.

a, b Zoomed-in view of the catalytic pocket of EcThrRS_G463A, which was crystallized in the presence of OB. The 2Fo-Fc electron densities of OB, Cys334, His385, His511, Tyr462 and Ala463 (contoured at 1.0 σ) are shown as transparent surfaces. OB does not form an ester bond with Tyr462. c Superimposition of the EcThrRS_Y462F–ATP structure (yellow cartoons, PDB code: 8H99) with the EcThrRS_G463A–OB structure (red cartoons). The nitrophenyl group of OB (in gray) binds between Phe379 and Arg520 where the adenine group of ATP (in purple blue) stacks. The orange parts in the middle of the panel are both terminal phosphate moieties of the cocrystallized ATP. d Superimposition of the EcThrRS_WT–OB structure (marine cartoons, PDB code: 8H98) with EcThrRS_G463A–OB (red cartoons). The ring-opened OB is shown as cyan sticks. The ring-closed OB is shown as gray sticks.

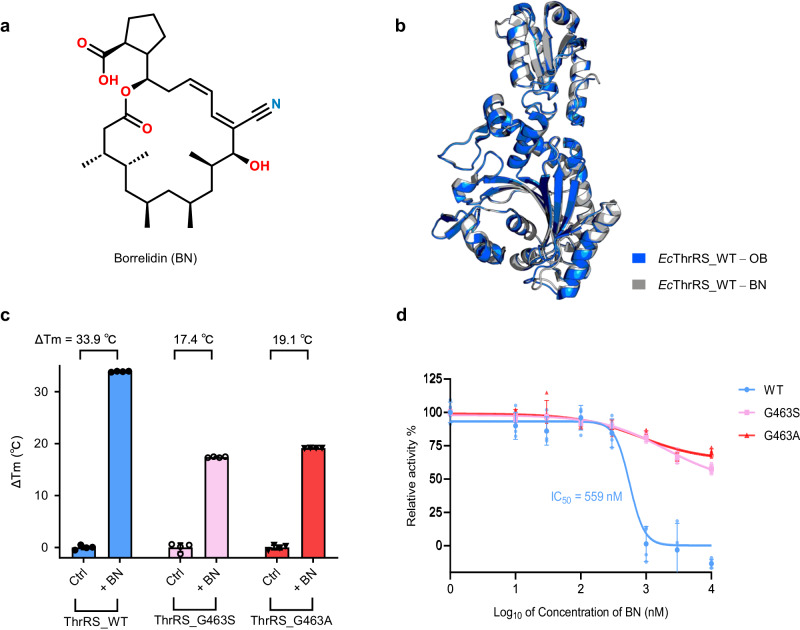

Conformation-constrained mutations cause resistance to conformation selective inhibitors

In addition to OB, another inhibitor molecule, borrelidin (BN, Fig. 7a), binds to ThrRS in an open conformation39. BN is an 18-member macrolide produced by Streptomyces rochei or Streptomyces parvulus. It binds ThrRS at a joint region of amino acid, ATP and tRNA pockets39–41. The BN binding conformation is very similar to the OB binding conformation (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7. Gly463 mutations also confer resistance of EcThrRS to BN.

a Chemical structure of borrelidin (BN). b Superimposition of the structures of EcThrRS_WT–OB (PDB code: 8H98, marine cartoons) with EcThrRS_WT–BN (PDB code: 4P3P, gray cartoons). The RMSD is 0.396 Å over 345 Cα atoms. c Diagram of the ΔTm values of EcThrRS_WT/G463S/G463A in the presence or absence of BN. Error bars represent the standard deviations (n = 4, mean value ± SD). All the data points are shown as small circles. d Inhibitory curves of BN on the ATP hydrolysis activity of EcThrRS_WT, G463S or G463A. Error bars represent the standard deviations (n = 4, mean value ± SD). All the data points for EcThrRS_WT/G463S/G463A are shown as pale blue dots, pale pink square dots, and pale red triangle dots.

We have shown that the pocket conformation of the G463S and G463A mutants in the lowest energy state is too small for OB to stably bind. By the same principle, they may also have some resistance to BN. We confirmed this hypothesis by TSA and ATP hydrolysis experiments. BN increased the Tm of EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_G463A by 17.4 °C and 19.1 °C, respectively, which were 16.5 °C and 14.8 °C lower than that of EcThrRS_WT (Fig. 7c). Similarly, BN had a strong inhibitory effect on EcThrRS_WT, with an IC50 value of 559 nM in the presence of 2 μM ATP and 20 μM l-Thr, but the inhibitory effect of both EcThrRS_G463S and EcThrRS_G463A decreased by more than 20-fold (Fig. 7d). These results suggest that conformation-constrained mutations also render ThrRS resistant to other conformation-selective inhibitors, such as BN.

Discussion

In summary, by studying the resistance of ObaO to OB, we found that a key glycine residue (Gly463) of ThrRS plays a dominant role in the molecular dynamics of the protein. Its substitution by small chiral amino acid residues significantly constrains the conformational space of ThrRS; therefore, we propose a general mechanism of ThrRS resistance to conformation-selective inhibitors, including OB and BN.

Gly463 is a highly conserved residue in the housekeeping ThrRSs. It is possible that the OB-resistant G463S substitution compromises enzyme activity. To our surprise, we found that the ATP hydrolysis activity of the Gly463 mutants was higher than that of the wild type (Supplementary Fig. 17). The mutation does not appear to have an adverse effect on the activity of the enzyme catalyzed amino acid activation. On the other hand, we noticed that the recombinant expression of Gly463 mutants produced more inclusion bodies than that of the wild type. Consistent with the discovery that Gly463 is critical to protein conformation, mutations in this residue may also sacrifice some of the cost of protein folding.

Functional proteins are in constant motion42. Structural flexibility allows proteins to adapt to their individual molecular binding partners and facilitates the binding process43. For example, the dynamics of bacterial leucyl-tRNA synthetase (LeuRS) allow for the whole catalytic cycle, while single mutations that affect global dynamics can reduce the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme44. Moreover, information such as the location and dynamic properties of drug binding pockets on proteins is critical for structure-based drug design and optimization of lead compounds45.

Considering the dynamics of protein pockets during drug development may increase the accuracy of pocket identification and reveal alternative shapes or even a new transient pocket43. For example, a recent retrospective structure-based virtual screen (SBVS) study showed that the exploration of binding pocket dynamics in SBVS of sirtuin 2 inhibitors could achieve significant improvements in screening performance46; a combination of experimental and computational methods of pocket dynamics successfully discovered an inhibitor that discriminates Plasmodium falciparum heat shock protein 90 from its human homolog47.

Although not widely studied, MD is also thought to give insight into the reasons for potential resistance development. For example, a combination of bioinformatics analysis and MD simulations showed that the L528W mutation of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) reduces the conformational stability of BTK and decreased its binding affinity to ibrutinib compared to that of the WT, leading to drug resistance and potential disease recurrence48.

In recent years, the development of drugs targeting aaRSs has received increasing amounts of attention. Our research suggested that molecular dynamics is an important factor in the design of drugs targeting aaRSs. This work not only elucidates the molecular mechanism of the self-resistance of OB-producing P. fluorescens that is equipped with a serine substitution at residue 464 (corresponding to Gly463 in EcThrRS) in the ObaO protein, but also emphasizes the importance of backbone kinetics, which is often hidden in static crystal structures, for aaRS-targeting drug development.

Methods

Protein purification

The E. coli ThrRS (residues 242-642, Supplementary Note 1) wild type, G463S, L489M, G463S_Q484A, G463A, A316N mutants, and the P. fluorescens ObaO (residues 241-637) and S464G mutant were constructed in a pET28a vector attended with a 6×His-tag at the C-terminus. Each protein was expressed in the BL21 (DE3) strain and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside for 20 h at 16 °C. The cell pellet (from 2 L) was lysed in buffer A (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, and 25 mM imidazole), loaded onto a Ni-Hitrap column (Cytiva, USA), washed with buffer A, and then eluted with a gradient increasing percentage of buffer B (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole) by a ӒKTA pure™ system (Cytiva, USA). The eluted protein was further purified by a Hitrap Q HP anion exchange column (Cytiva, USA) with gradient NaCl buffer (0.05–1 M NaCl in 25 mM Tris pH 7.5).

Crystallization

For crystallization, the protein was further purified by a gel filtration S200 Increase column (Cytiva, USA) with a buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM MgCl2. All crystallization experiments were performed at 18 °C based on the sitting-drop method49. All proteins were concentrated to 15 mg/mL using a 10 kDa centrifugal filter (Millipore, USA). Before crystallization, OB (GlpBio, US) was mixed with protein at twice the molar ratio on ice for 1 h. ATP was mixed with protein at a fivefold molar ratio on ice for 1 h if added. For the microbatch crystallization screen, 0.5 μL of protein solution was mixed with an equal amount of precipitant solution (Molecular dimensions, UK) in microbatch 96-well plates using a Gryphon robot (ART technology, USA). Crystals grew to their final dimensions within 1–3 days.

The EcThrRS_G463S crystals were obtained from the condition of 0.02 M sodium formate, 0.02 M ammonium acetate, 0.02 M sodium citrate tribasic, 0.02 M potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate, 0.02 M sodium oxamate, 0.045 M imidazole, 0.055 M MES monohydrate pH 6.5, 20% v/v PEG 500 MME, and 10% w/v PEG 20000.

The EcThrRS_L489M–OB crystals were obtained from the condition of 2.0 M ammonium sulfate, and 0.15 M sodium citrate pH 5.5. 0.02 M DL-glutamic acid monohydrate, 0.02 M DL-alanine, 0.02 M glycine, 0.02 M DL-lysine monohydrochloride, 0.02 M DL-serine, 0.061 M Tris, 0.039 M bicine pH 8.5, 12.5% v/v MPD, 12.5% w/v PEG 1000, and 12.5% w/v PEG 3350.

The EcThrRS_G463S_Q484A crystals were obtained from the condition of 0.03 M magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.03 M calcium chloride dihydrate, 0.05 M sodium HEPES, 0.05 M MOPS pH 7.5, 20% v/v PEG 500 MME, and 10% w/v PEG 20000.

The EcThrRS_G463A–OB crystals were obtained from the condition of 0.02 M D-glucose, 0.02 M D-mannose, 0.02 M D-galactose, 0.02 M L-fucose, 0.02 M D-xylose, 0.02 M N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, 0.05 M sodium HEPES, 0.05 M MOPS pH 7.5, 12.5% v/v MPD, 12.5% w/v PEG 1000, and 12.5% w/v PEG 3350.

The EcThrRS_G463A–OB crystals were obtained from the condition of 0.03 M diethylene glycol, 0.03 M triethylene glycol, 0.03 M tetraethylene glycol, 0.03 M pentaethylene glycol, 0.05 M sodium HEPES, 0.05 M MOPS pH 7.5, 20% v/v ethylene glycol, and 10% w/v PEG 8000.

The EcThrRS_G463A–ATP crystals were obtained from the condition of 0.03 M magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.03 M calcium chloride dihydrate, 0.045 M imidazole, 0.055 M MES monohydrate pH 6.5, 20% v/v glycerol, and 10% w/v PEG 4000.

Data collection and structure determination

The resulting crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for data collection. The data were obtained from beamlines 10U2 or 02U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). Then, the datasets were indexed and integrated with XDS50 or automatically processed by AutoPROC51 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The HKL files were scaled and merged with Aimless in the CCP4 suite52. The structures were determined by molecular replacement using the EcThrRS–OB structure (PDB: 8H98) or the EcThrRS structure (PDB: 1EVK) as a searching model in the Phaser program in the CCP4 suite53. After corrections for the bulk solvent and overall B values, the data were refined by iterative cycles of positional refinement and TLS refinement with PHENIX54 and model building with COOT55. All current models had good geometry and no residues were in the disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot. The data collection and model statistics are given in Supplementary Tables 1–5.

Thermal shift assay

The EcThrRS_WT and L489M/G463S/G463S_Q484A/G463A/A316N mutant proteins, ObaO_WT and ObaO_S464G mutant proteins were prepared at 2 μM in buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 20 μM OB (GlpBio, US) or BN (GlpBio, US) or ddH2O in equal volumes since the compounds were diluted with ddH2O to 1 mM as stocks. Compound 36j was assayed at the same final concentration as a positive control. SYPRO orange dye (Sigma, USA) was diluted in assay buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 200 mM NaCl to a 40× concentration, and was added to the mixture to a final 4× concentration. Aliquots (20 μL) were added to a 96-well PCR plate. After complete mixing, the final solutions were heated from 25 to 95 °C at a rate of 0.015 °C/s, and fluorescence signals were monitored by QuantStudio 3 (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The melting temperature (Tm) was calculated through a previously established method56,57.

ATP hydrolysis assay

200 nM EcThrRS wide type and mutants, ObaO and ObaO_S464G mutant were incubated with serially diluted OB (0 to 10 μM for EcThrRS, 0 to 40 μM for ObaO) in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 40 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 0.01 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.004% Tween-20 at 37 °C for 4 h and then mixed 1:1 with a substrate mixture containing 4 μM ATP, 40 μM l-threonine, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 40 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 0.01 mg/mL BSA, and 0.004% Tween-20. The ATP hydrolysis reaction was performed at 37 °C for 4 h.

To evaluate the relative ATP hydrolysis rate of EcThrRS_WT, Y462F, G463S and G463A, a reaction mixture containing 200 nM EcThrRS, 2 μM ATP, 20 μM l-threonine, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 40 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 0.01 mg/mL BSA, and 0.004% Tween-20 was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h.

After incubation, the detection solution from the Kinase-Glo® luminescent kit (Promega, USA) was added to the reaction system at a 1:1 ratio, and the mixture was gently shaken for 10 min. The chemiluminescence signal was measured using a microplate reader (Tecan, USA). All experiments were performed in four replicates. The data were processed using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

MD simulations were performed by using the Desmond58 package of Schrödinger2023-1 with the OPLS4 force field59. The initial conformation of EcThrRS_G463S was obtained from the crystal structure determined in this work. To maintain consistency in the MD starting point and explore the inherent conformational space, the initial conformations of EcThrRS_WT and EcThrRS_G463A were obtained from a single mutation of the EcThrRS_G463S crystal structure. All systems were explicitly solvated with TIP3P water molecules60 under cubic periodic boundary conditions for a 15 Å buffer region. The overlapping water molecules were removed, 0.15 M KCl was added, and the system was neutralized by adding K+ as a counter ion. Brownian motion simulation was used to relax these systems into local energy minimum states separately. An ensemble (NPT) was then applied to maintain a constant temperature (310 K) and pressure (1.01325 bar) of the systems. For EcThrRS_WT and the two introduced mutants, 8 sets of simulations with different random initial velocities were started at 310 K, with each set lasting 400 ns. The simulations described above were performed using the AutoMD61 (https://github.com/Wang-Lin-boop/AutoMD) script to handle the system and control the simulation process. To avoid artifacts caused by periodicity, we processed the trajectory using trj_center.py. The distance between residue pairs was monitored by using trajectory_asl_monitor.py. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) and radius of gyration (Rg) were calculated by using analyze_simulation.py. Gromacs sham62 and Matplotlib were used to calculate and visualize the three-dimensional Gibbs free energy surface with RMSD and Rg. The dynamic cross-correlation matrix (DCCM) was calculated and plotted by using the script trj_essential_dynamics.py. The process and analysis of trajectories described above were performed using the AutoTRJ (https://github.com/Wang-Lin-boop/AutoMD/blob/main/AutoTRJ) script. All of these simulation analysis scripts are from Schrödinger, Inc. The dynamics simulation movies were visualized by using VMD.

Statistics and reproducibility

Enzymatic assay and thermal shift measurements were conducted in four repeats. MD simulations were conducted in eight repeats with different random initial velocities. Acquired data are presented as the mean values ± standard deviation (SD).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Huihao Zhou for his helpful discussion and generous supply of compound 36j. We gratefully acknowledge the help from the staff of beamlines 10U2 and 02U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China grant 2022YFC2303100, National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 22277132 and 22277134, Shanghai Science and Technology Committee grant 22ZR1475000, the State Key Laboratory of Chemical Biology, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Construction Foundation, 2023B1212060022, and funding support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3400500 and 2022YFC3400501) and the Shanghai Frontiers Science Center for Biomacromolecules and Precision Medicine at ShanghaiTech University. We also thank the HPC Platform of ShanghaiTech University.

Author contributions

Investigation and methodology, H.Q., Z.W., H.Y., M.X. and G.Y.; review, editing, and writing, H.Q., Z.W., H.Y., F.B., J.W., and P.F.; conceptualization and supervision, F.B., J.W., and P.F. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Charles W. Carter Jr and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Tuan Anh Nguyen and Christina Karlsson Rosenthal. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 8WIH, 8WIG, 8WII, 8WIA, and 8WIJ. The source data behind the graphs are available as Supplementary Data 1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hang Qiao, Zilu Wang, Hao Yang.

Contributor Information

Fang Bai, Email: baifang@shanghaitech.edu.cn.

Jing Wang, Email: JWang@sioc.ac.cn.

Pengfei Fang, Email: FangPengfei@sioc.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-06559-x.

References

- 1.Carter CW, Jr, Wills PR. The roots of genetic coding in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase duality. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021;90:349–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-071620-021218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio Gomez MA, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Rna. 2020;26:910–936. doi: 10.1261/rna.071720.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pang, L., Weeks, S. D. & Van Aerschot, A. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases as valuable targets for antimicrobial drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Xie SC, Griffin MDW, Winzeler EA, Ribas de Pouplana L, Tilley L. Targeting aminoacyl tRNA synthetases for antimalarial drug development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2023;77:111–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-032421-121210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon NH, Fox PL, Kim S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:629–650. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neenan TX, Burrier RE, Kim S. Biocon’s target factory. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:791–797. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JH, et al. Control of leucine-dependent mTORC1 pathway through chemical intervention of leucyl-tRNA synthetase and RagD interaction. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:732. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00785-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim DG, et al. Chemical inhibition of prometastatic lysyl-tRNA synthetase-laminin receptor interaction. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:29–34. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang P, Guo M. Evolutionary limitation and opportunities for developing tRNA synthetase inhibitors with 5-binding-mode classification. Life. 2015;5:1703–1725. doi: 10.3390/life5041703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou H, Sun L, Yang XL, Schimmel P. ATP-directed capture of bioactive herbal-based medicine on human tRNA synthetase. Nature. 2013;494:121–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baragana B, et al. Lysyl-tRNA synthetase as a drug target in malaria and cryptosporidiosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:7015–7020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814685116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams TL, Yin YW, Carter CW., Jr. Selective inhibition of bacterial Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetases by indolmycin is mechanism-based. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:255–265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.690321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou J, et al. Atomic resolution analyses of isocoumarin derivatives for inhibition of Lysyl-tRNA synthetase. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020;15:1016–1025. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.0c00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen B, et al. Inhibitory mechanism of reveromycin A at the tRNA binding site of a class I synthetase. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1616. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21902-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rock FL, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759–1761. doi: 10.1126/science.1142189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Ruysscher D, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity studies of novel anhydrohexitol-based Leucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors. Eur. J. Medicinal Chem. 2021;211:113021. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teng M, et al. Identification of bacteria-selective threonyl-tRNA synthetase substrate inhibitors by structure-based design. J. Medicinal Chem. 2013;56:1748–1760. doi: 10.1021/jm301756m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abibi A, et al. The role of a novel auxiliary pocket in bacterial phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase druggability. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:21651–21662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.574061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma M, et al. Structural basis of malaria parasite phenylalanine tRNA-synthetase inhibition by bicyclic azetidines. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:343. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20478-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J, et al. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum Lysyl-tRNA synthetase via an anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:11566–11576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Z, et al. Design, Synthesis, and Proof-of-Concept of Triple-Site Inhibitors against Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. J. Medicinal Chem. 2022;65:5800–5820. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vondenhoff GH, et al. Extended targeting potential and improved synthesis of Microcin C analogs as antibacterials. Bioorg. Medicinal Chem. 2011;19:5462–5467. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chopra S, et al. Plant tumour biocontrol agent employs a tRNA-dependent mechanism to inhibit leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1417. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, et al. Structural characterization of free-state and product-state Mycobacterium tuberculosis methionyl-tRNA synthetase reveals an induced-fit ligand-recognition mechanism. IUCrJ. 2018;5:478–490. doi: 10.1107/S2052252518008217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie SC, et al. Reaction hijacking of tyrosine tRNA synthetase as a new whole-of-life-cycle antimalarial strategy. Science. 2022;376:1074–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.abn0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott TA, et al. Immunity-guided identification of threonyl-tRNA synthetase as the molecular target of obafluorin, a beta-lactone antibiotic. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019;14:2663–2671. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells JS, Trejo WH, Principe PA, Sykes RB. Obafluorin, a novel beta-lactone produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Taxonomy, fermentation and biological properties. J. Antibiotics. 1984;37:802–803. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar P, et al. l-Threonine transaldolase activity is enabled by a persistent catalytic intermediate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021;16:86–95. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.0c00753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaffer JE, Reck MR, Prasad NK, Wencewicz TA. beta-Lactone formation during product release from a nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:737–744. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott TA, Heine D, Qin Z, Wilkinson B. An L-threonine transaldolase is required for L-threo-beta-hydroxy-alpha-amino acid assembly during obafluorin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15935. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreitler DF, Gemmell EM, Schaffer JE, Wencewicz TA, Gulick AM. The structural basis of N-acyl-alpha-amino-beta-lactone formation catalyzed by a nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones MA, et al. Discovery of L-threonine transaldolases for enhanced biosynthesis of beta-hydroxylated amino acids. Commun. Biol. 2023;6:929. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-05293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batey SFD, et al. The catechol moiety of obafluorin is essential for antibacterial activity. RSC Chem. Biol. 2023;4:926–941. doi: 10.1039/D3CB00127J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao H, et al. Tyrosine-targeted covalent inhibition of a tRNA synthetase aided by zinc ion. Commun. Biol. 2023;6:107. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04517-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankaranarayanan R, et al. The structure of threonyl-tRNA synthetase-tRNA(Thr) complex enlightens its repressor activity and reveals an essential zinc ion in the active site. Cell. 1999;97:371–381. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ichiye T, Karplus M. Collective motions in proteins: a covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular dynamics and normal mode simulations. Proteins. 1991;11:205–217. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnold GE, Ornstein RL. Molecular dynamics study of time-correlated protein domain motions and molecular flexibility: cytochrome P450BM-3. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang P, et al. Structural basis for full-spectrum inhibition of translational functions on a tRNA synthetase. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6402. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olano C, et al. Biosynthesis of the angiogenesis inhibitor borrelidin by Streptomyces parvulus Tu4055: cluster analysis and assignment of functions. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu CX, et al. Antifungal activity of borrelidin produced by a Streptomyces strain isolated from soybean. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:1251–1257. doi: 10.1021/jf2044982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller MD, Phillips GN., Jr Moving beyond static snapshots: Protein dynamics and the Protein Data Bank. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;296:100749. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stank A, Kokh DB, Fuller JC, Wade RC. Protein binding pocket dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:809–815. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pang L, et al. Partitioning of the initial catalytic steps of leucyl-tRNA synthetase is driven by an active site peptide-plane flip. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:883. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03825-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nisius B, Sha F, Gohlke H. Structure-based computational analysis of protein binding sites for function and druggability prediction. J. Biotechnol. 2012;159:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Djokovic N, et al. Expanding the accessible chemical space of SIRT2 inhibitors through exploration of binding pocket dynamics. J. Chem. Inform. Modeling. 2022;62:2571–2585. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.2c00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang T, Bisson WH, Maser P, Scapozza L, Picard D. Differences in conformational dynamics between Plasmodium falciparum and human Hsp90 orthologues enable the structure-based discovery of pathogen-selective inhibitors. J. Medicinal Chem. 2014;57:2524–2535. doi: 10.1021/jm401801t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu B, Liang L, Jiang Y, Zhao Z. Investigating the ibrutinib resistance mechanism of L528W mutation on Bruton’s tyrosine kinase via molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Graphics Modelling. 2024;126:108623. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2023.108623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adachi H, et al. Application of a two-liquid system to sitting-drop vapour-diffusion protein crystallization. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2003;59:194–196. doi: 10.1107/S0907444902019741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vonrhein C, et al. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:293–302. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pantoliano MW, et al. High-density miniaturized thermal shift assays as a general strategy for drug discovery. J. Biomol. Screening. 2001;6:429–440. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fang P, et al. Structural basis for specific inhibition of tRNA synthetase by an ATP competitive inhibitor. Chem. Biol. 2015;22:734–744. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowers, K. J. et al. In: SC ‘06: Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing 43–43 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2006). 10.1109/SC.2006.54.

- 59.Lu C, et al. OPLS4: improving force field accuracy on challenging regimes of chemical space. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021;17:4291–4300. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gillan MJ, Alfe D, Michaelides A. Perspective: How good is DFT for water? J Chem Phys. 2016;144:130901. doi: 10.1063/1.4944633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liang L, et al. A new variant of the colistin resistance gene MCR-1 with co-resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics reveals a potential novel antimicrobial peptide. PLoS Biol. 2023;21:e3002433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abraham MJ, et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1-2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 8WIH, 8WIG, 8WII, 8WIA, and 8WIJ. The source data behind the graphs are available as Supplementary Data 1.