This open-label extension study of a randomized clinical trial investigates 3-year outcomes of paliperidone palmitate injection once every 6 months among adults with schizophrenia.

Key Points

Question

What are the long-term outcomes of paliperidone palmitate (PP) once every 6 months in adults with schizophrenia?

Findings

In an open-label extension study of a randomized clinical trial that included 121 patients receiving PP every 6 months, all were clinically and functionally stable, and outcomes were well maintained, with 95.9% of patients remaining relapse free for up to 3 years. No deaths were reported, and no new safety concerns outside the adverse event profile of the drug were identified.

Meaning

These results support favorable long-term outcomes of PP once every 6 months for up to 3 years in adults with schizophrenia.

Abstract

Importance

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have the potential to improve adherence and symptom control in patients with schizophrenia, promoting long-term recovery. Paliperidone palmitate (PP) once every 6 months is the first and currently only LAI antipsychotic with an extended dosing interval of 6 months.

Objective

To assess long-term outcomes of PP received once every 6 months in adults with schizophrenia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In a 2-year open-label extension (OLE) study of a 1-year randomized clinical trial (RCT), eligible adults with schizophrenia could choose to continue PP every 6 months if they had not experienced relapse after receiving PP once every 3 or 6 months in the 1-year, international, multicenter, double-blind, randomized noninferiority trial. The present analysis focused on patients receiving PP every 6 months in the double-blind trial through the OLE study (November 20, 2017, to May 3, 2022).

Intervention

Patients received a dorsogluteal injection of PP on day 1 and once every 6 months up to month 30.

Main Outcomes and Measures

End points included assessment of relapse and change from the double-blind trial baseline to the OLE end point in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total and subscale, Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) Scale, and Personal Social Performance (PSP) Scale scores. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), injection site evaluations, and laboratory tests were also assessed.

Results

Among 121 patients (83 [68.6%] male), mean (SD) age at baseline was 38.6 (11.24) years and mean (SD) duration of illness was 11.0 (9.45) years. At screening of the double-blind study, 101 patients (83.5%) were taking an oral antipsychotic and 20 (16.5%) were taking an LAI antipsychotic. Altogether, 5 of 121 patients (4.1%) experienced relapse during the 3-year follow-up; reasons for relapse were psychiatric hospitalization (2 [1.7%]), suicidal or homicidal ideation (2 [1.7%]), and deliberate self-injury (1 [0.8%]). Patients treated with PP every 6 months were clinically and functionally stable, and outcomes were well maintained, evidenced by stable scores on the PANSS (mean [SD] change, −2.6 [9.96] points), CGI-S (mean [SD] change, −0.2 [0.57] points), and PSP (mean [SD] change, 3.1 [9.14] points) scales over the 3-year period. In total, 101 patients (83.5%) completed the 2-year OLE. At least 1 TEAE was reported in 97 of 121 patients (80.2%) overall; no new safety or tolerability concerns were identified.

Conclusions and Relevance

In a 2-year OLE study of a 1-year RCT, results supported favorable long-term outcomes of PP once every 6 months for up to 3 years in adults with schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating mental illness that affects approximately 24 million people (0.3%) worldwide.1 Patients with schizophrenia require lifelong treatment with antipsychotic medications; additionally, many experience reduced quality of life resulting from periods of exacerbated active symptoms leading to repeated hospitalizations, loss of productivity, incarceration, and mortality often due to nonadherence to medications.2,3,4 Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have the potential to improve treatment adherence and symptom control in patients with schizophrenia and have demonstrated superior efficacy compared with oral antipsychotics.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 In a randomized pragmatic study including clinical sampling of a diverse population of patients with schizophrenia, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP) demonstrated significant reductions in hospitalizations, incarcerations, and treatment failure compared with oral antipsychotics.5 Certain first- and second-generation antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, olanzapine, paliperidone, and risperidone, are available in LAI formulations.12 LAI antipsychotics differ in their pharmacokinetic properties and, as a result, in their initiation protocols and dosing intervals.13

Paliperidone palmitate (PP) is an LAI that has been shown to be effective in maintaining symptom control, reducing risk of relapse, and delaying time to relapse in schizophrenia.5,7,14,15,16,17,18,19 Paliperidone palmitate is available in 3 formulations: once monthly,20 once every 3 months,21 and a recently developed formulation of once every 6 months.22 Paliperidone palmitate is the first (and currently only) LAI with a 6-month dosing interval, which is substantially longer than any other LAI antipsychotic. Treatment with PP every 6 months permits just 2 injections per year for patients who have been adequately treated with PP once monthly for 4 months or longer or PP every 3 months for at least 1 injection cycle.7,16,22 Observational studies have suggested that there may be an advantage to longer injection intervals of LAI antipsychotics for greater medication treatment persistence,23 which is a challenge with both oral medications and LAIs.24 This analysis assessed the long-term outcomes of PP every 6 months in adults with schizophrenia.7,16

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This secondary analysis included patients from a 1-year, double-blind randomized clinical trial (NCT03345342) through a 2-year, single-arm, open-label extension (OLE) study (NCT04072575). Studies were approved by the independent ethics committees or institutional review boards of the respective sites and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki,25 Good Clinical Practice, and applicable regulatory requirements. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in this study. We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1.

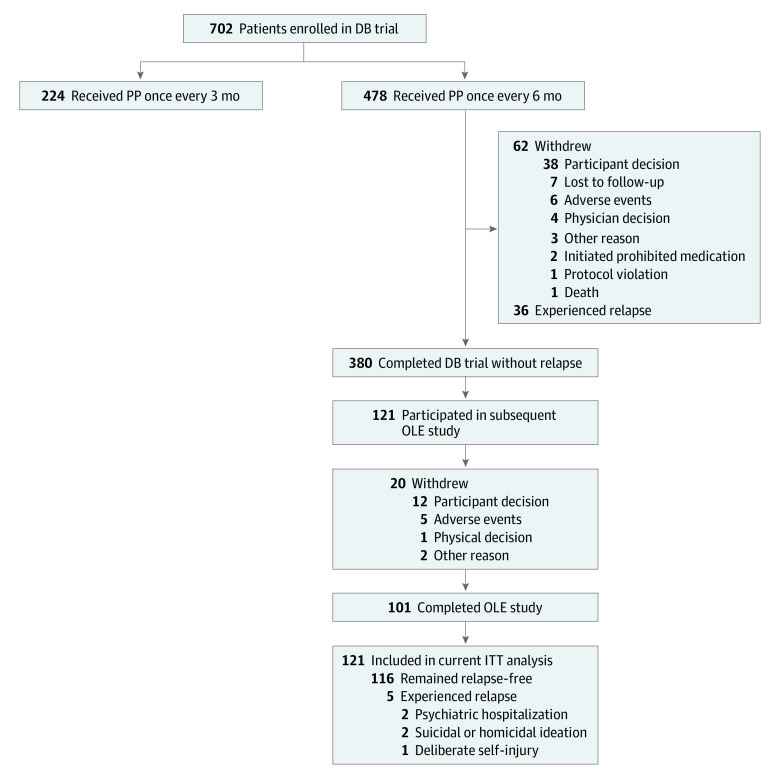

Eligible patients were men and women aged 18 to 70 years with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) diagnosis of schizophrenia for 6 or more months before screening and a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of less than 70 points at screening (score range, 30-210, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity). After screening and open-label transition and maintenance phases, clinically stable patients receiving moderate or high doses of PP once monthly (moderate, 156 mg [100-mg equivalent of paliperidone]; high, 234 mg [150-mg equivalent of paliperidone]) or every 3 months (moderate, 546 mg [350-mg equivalent of paliperidone]; high, 819 mg [525-mg equivalent of paliperidone]) were randomly assigned 2:1 to corresponding dorsogluteal injections of PP every 6 months (moderate, 1092 mg [700-mg equivalent of paliperidone]; high, 1560 mg [1000-mg equivalent of paliperidone]) or PP every 3 months (moderate, 546 mg [350-mg equivalent of paliperidone]; high, 819 mg [525-mg equivalent of paliperidone]) during the double-blind trial.7 Eligible patients from 6 countries (Argentina, Hong Kong, Italy, Poland, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine) who completed the double-blind trial without experiencing relapse after receiving PP every 3 or 6 months and wished to continue treatment with PP every 6 months enrolled in the 2-year OLE study (Figure 1). This analysis focused on patients receiving PP every 6 months in the double-blind trial through the OLE study (study period, November 20, 2017, to May 3, 2022).

Figure 1. Study Participant Flowchart.

Relapse criteria for the double-blind (DB) study included psychiatric hospitalization, emergency department visit due to schizophrenia symptoms, participant behavior resulting in harm (self-injury, suicide, harm to another person, property damage, and/or suicidal or homicidal ideation and aggressive behavior), a 25% increase in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score from randomization (for patients with PANSS score >40 at randomization) or 10-point increase (for patients with PANSS score ≤40 at randomization) in PANSS total score from randomization for 2 consecutive assessments between 3 to 7 days, or PANSS scores of 5 or greater after randomization (if PANSS score was ≤3 at randomization) or 6 or greater (if PANSS score was 4 at randomization) after randomization for 2 consecutive assessments between 3 and 7 days on any of the following items: delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness or persecution, hostility, and uncooperativeness. ITT indicates intent-to-treat; OLE, open-label extension; PP, paliperidone palmitate.

During the OLE study, antiextrapyramidal symptom medications, benzodiazepines, sleep aids, and oral antipsychotics were permitted. Antipsychotic supplementation dose and duration were dependent on symptom exacerbation and the investigator’s judgment. Permitted oral antipsychotic medications included oral risperidone (moderate dose: 1-2 mg/d and high dose: 1-3 mg/d) and oral paliperidone extended release (moderate dose: 1.5-3 mg/d and high dose: 1.5-6 mg/d).16 Coadministration with PP every 6 months had a maximum duration of 2 weeks. If the participant did not meet relapse criteria within a single 6-month injection cycle, an additional 2 weeks of oral antipsychotic was administered continuously for a maximum of 4 weeks. Per investigator’s discretion, if there was a clinical need for oral antipsychotic supplementation for greater than 4 continuous weeks, the study intervention was discontinued and the participant was withdrawn. Use of oral antipsychotic medications other than oral risperidone or oral paliperidone extended release was prohibited.16

Study End Points and Assessments

Relapse in the OLE study was defined as 1 or more of the following: psychiatric hospitalization, emergency department visit due to schizophrenia symptoms, participant behavior resulting in harm (self-injury, suicide, harm to another person, or property damage), and/or suicidal or homicidal ideation or aggressive behavior. In the double-blind trial, relapse criteria also included specific increases in PANSS total and subscale scores.

Changes from the double-blind trial baseline to the OLE study end point in PANSS total and subscale scores and in scores on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) Scale (score range, 1-7 and baseline range, 1-5, with higher scores indicating more severe illness) and Personal and Social Performance (PSP) Scale (score range, 45-100, with higher scores indicating better personal and social functioning) were included as secondary end points. The PANSS and PSP assessments occurred at baseline (in the double-blind trial) and at months 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 36 (OLE study end point). The CGI-S assessments occurred at week 4 and then monthly up to 12 months after baseline (in the double-blind trial), after which point, data were collected every 3 months. Data are presented as collected; no missing data points were imputed. To ensure consistent use of the assessment tools, all raters were trained and certified.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), mental status examination, injection site evaluations, and clinical laboratory tests were also assessed. Blood samples for serum chemistry and hematology and urine samples for urinalysis were collected.

Statistical Analysis

All patients who received at least 1 dose of PP every 6 months during the OLE study were included in the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis population. Outcomes were summarized descriptively. Subgroup analyses of outcomes were conducted using a mixed-model, repeated-measures analysis of covariance; these were exploratory analyses with no adjustment for multiplicity. Analyses were based on change from baseline in the double-blind trial in PANSS, CGI-S, and PSP scores at each visit for subgroups by age (18-25, >25 to 50, or >50 years), sex, body mass index (BMI) (<30 or ≥30; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), and duration of illness (≤3 years or >3 years). Data were analyzed using SAS, version 15.1 (SAS Institute Inc). The statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 1.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 121 patients were included in this 3-year ITT analysis (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of patients was 38.6 (11.24) years; 38 (31.4%) were female and 83 (68.6%) were male. Mean (SD) baseline BMI was 27.9 (4.84). Mean (SD) duration of illness was 11.0 (9.45) years. At screening of the double-blind study, 101 patients (83.5%) were taking an oral antipsychotic and 20 (16.5%) were taking an LAI antipsychotic (injectable risperidone, PP once monthly, or PP every 3 months). Patients were observed for a median of 3.0 years (range, 1.0-3.1 years). Participants received either 1092-mg (700-mg equivalent of paliperidone; 3.5 mL) or 1560-mg (1000-mg equivalent of paliperidone; 5.0 mL) doses of PP every 6 months in prefilled syringes at each time point, and flexible dosing was allowed during the OLE study. Mean (SD) dose of PP every 6 months was 1367.7 mg (876.7-mg equivalent of paliperidone) (217.3 mg; 139.3-mg equivalent of paliperidone).

Table 1. Demographics and Disease Characteristics Among Patients Receiving PP Every 6 Months at Baseline in the Double-Blind Trial.

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 121)a |

|---|---|

| Age, yb | 38.6 (11.24) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Female | 38 (31.4) |

| Male | 83 (68.6) |

| Baseline BMI | 27.9 (4.84) |

| Age at first diagnosis of schizophrenia, y | 27.5 (9.21) |

| Duration of illness, y | 11.0 (9.45) |

| Duration of psychiatric hospitalization prior to study entry, dc | 61.0 (43.08) |

| PANSS scored | 53.4 (9.72) |

| PSP scoree | 68.7 (12.10) |

| CGI-S scoref | 3.0 (0.77) |

| Previous medication, No. (%) | |

| Oral antipsychotic with reason to change | 101 (83.5) |

| Long-acting injectable | 20 (16.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PP, paliperidone palmitate; PSP, Personal and Social Performance scale.

Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

Age at screening visit.

A total of 47 patients had psychiatric hospitalization prior to study entry.

Score range, 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Score range, 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating better personal and social functioning.

Score range, 1 to 7 and baseline range 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe illness.

Outcomes

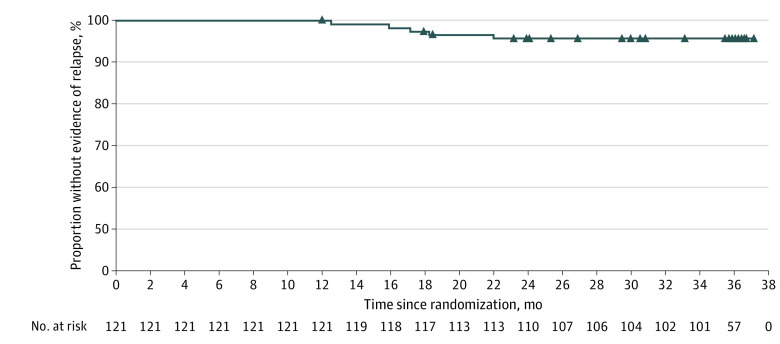

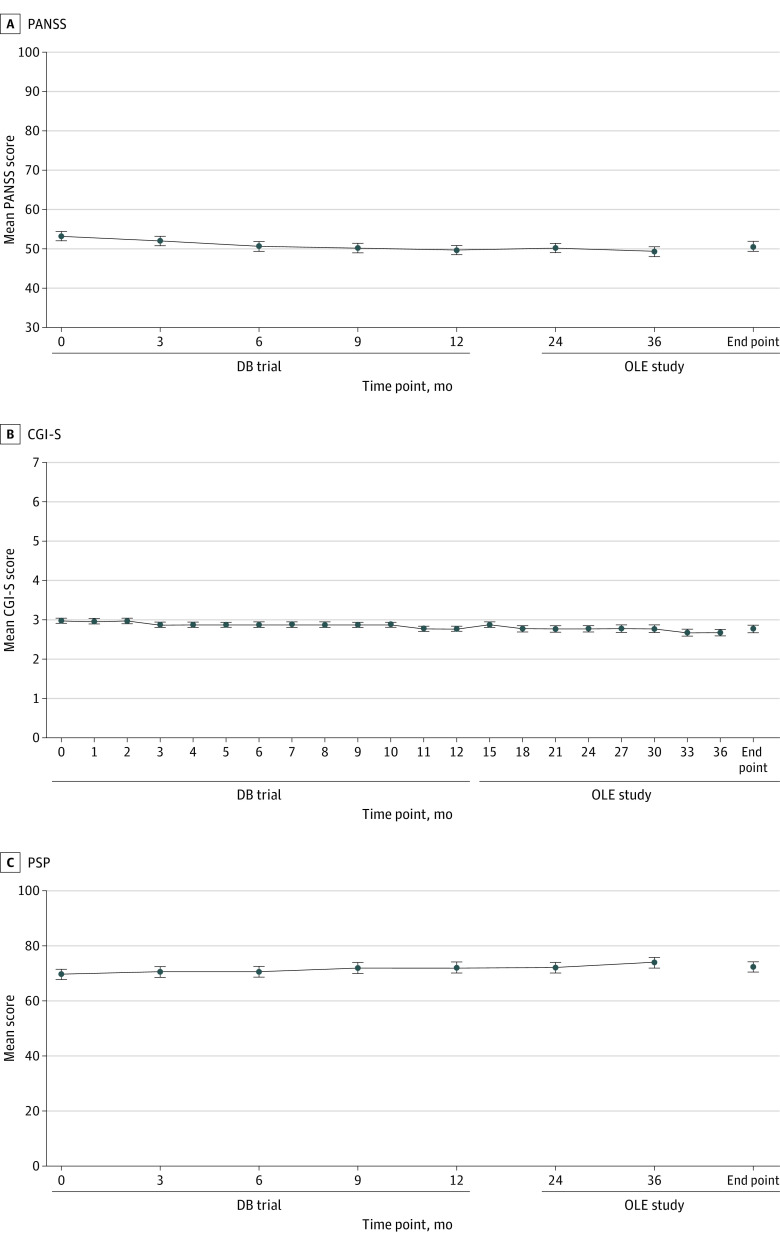

Five of 121 patients (4.1%) experienced relapse during the 3-year follow-up period (Figure 2). The reasons for relapse were psychiatric hospitalization (2 patients [1.7%]), suicidal or homicidal ideation (2 [1.7%]), and deliberate self-injury (1 [0.8%]). Patients treated with PP every 6 months were clinically stable and outcomes were well maintained, as evidenced by stable PANSS, CGI-S, and PSP scores over the 3-year period (Figure 3). Mean (SD) change from baseline to end point in PANSS total score was −2.6 (9.96) points, CGI-S score was −0.2 (0.57) points, and PSP total score was 3.1 (9.14) points. Altogether, 101 of 121 patients (83.5%) completed the 2-year follow-up period.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plot of Time to Relapse Over 3 Years of Paliperidone Palmitate Use Once Every 6 Months.

Only patients who were relapse free during the 1-year, double-blind, randomized clinical trial (first 12 months) were included in this analysis.

Figure 3. Mean PANSS, CGI-S, and PSP Total Scores Over Time From the Double-Blind (DB) Trial to the End of the Open-Label Extension (OLE) Study.

Errors bars indicate SDs. CGI-S indicates Clinical Global Impression–Severity Scale (score range, 1-7 and baseline range, 1-5, with higher scores indicating more severe illness); PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (score range, 30-210, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity); PSP, Personal and Social Performance Scale (score range, 45-100, with higher scores indicating better personal and social functioning).

Overall evaluations of end points by age, sex, duration of illness, and BMI showed improvements over 3 years. Directional improvements within each subgroup did not deviate from the overall findings, and there were no statistically significant differences among the groups with the exception of CGI-S scores by sex, which showed that, in general, scores for female patients improved to a greater extent than those for male patients after 6 months. Subgroup estimate data for each scale (CGI-S, PANSS, and PSP) are included in eTables 1 to 12 in Supplement 2.

Overall, 97 patients (80.2%) experienced 1 or more TEAEs (Table 2); TEAEs deemed possibly related to treatment with PP every 6 months were reported in 65 patients (53.7%). The most common TEAEs as entered in the database (occurring in ≥5% of patients) were headache (22 [18.2%]), weight increased (15 [12.4%]), blood prolactin increased (14 [11.6%]), nasopharyngitis (13 [10.7%]), injection site pain (13 [10.7%]), diarrhea (10 [8.3%]), hyperprolactinemia (9 [7.4%]), blood thyroid stimulating hormone increased (6 [5.0%]), and back pain (6 [5.0%]). Most TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity and were consistent with those reported in other studies.5,14,15,17,18

Table 2. Summary of TEAEs Among Patients Receiving PP Every 6 Months.

| TEAE | Patients (N = 121)a |

|---|---|

| Possibly related to treatment | 65 (53.7) |

| ≥1 Any grade | 97 (80.2) |

| ≥1 Serious | 7 (5.8) |

| Leading to drug withdrawn | 6 (5.0) |

| Leading to death | 0 |

| Occurring in ≥5% of patients | |

| Blood prolactin increased or hyperprolactinemiab | |

| Any | 23 (19.0) |

| Blood prolactin increased | 14 (11.6) |

| Hyperprolactinemia | 9 (7.4) |

| Headache | 22 (18.2) |

| Weight gain | |

| Weight increased | 15 (12.4) |

| Weight increase of ≥7% at month 36 | 7 (7.2) |

| Weight change from baseline at month 36, mean (SD), kg | 0.96 (6.7) |

| BMI change from baseline at month 36, mean (SD) | 0.3 (2.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 13 (10.7) |

| Injection site pain | 13 (10.7) |

| Diarrhea | 10 (8.3) |

| Back pain | 6 (5.0) |

| Blood thyroid-stimulating hormone increased | 6 (5.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); PP, paliperidone palmitate; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Both “blood prolactin increased” and “hyperprolactinemia” are Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terms and thus are listed separately and were chosen per investigator discretion. There were no overlapping patients between these 2 categories.

Seven patients (5.8%) experienced at least 1 serious TEAE, entered in the database as schizophrenia (3 [2.5%]), depression (1 [0.8%]), psychiatric symptom (1 [0.8%]), colon cancer (1 [0.8%]), cancer metastases to peritoneum (1 [0.8%]), and nephrotic syndrome (1 [0.8%]). Six patients (5.0%) experienced at least 1 TEAE leading to drug withdrawal: psychiatric disorders (5 [4.1%]), including schizophrenia (4 [3.3%]), intrusive thoughts (1 [0.8%]), psychiatric symptom (1 [0.8%]), and suicidal ideation (1 [0.8%]), and general disorders and administration site conditions (1 [0.8%]), including injection site edema, injection site pain, and injection site warmth. No deaths were reported in the cohort.

Discussion

Results from this analysis revealed favorable long-term outcomes, with an adverse event profile consistent with previous studies of paliperidone,5,7,14,15,16,17,18,19 of PP every 6 months for up to 3 years in adults with schizophrenia. Of the 121 patients receiving PP every 6 months who completed the 1-year double-blind trial without relapse and continued into the 2-year OLE study, 116 patients (95.9%) remained relapse free, with 83.5% completing the entire 2-year follow-up. This result was similar to the primary results observed for the OLE study, in which 96.1% of patients receiving PP every 6 months remained relapse free for up to 2 years.16 Furthermore, patients receiving PP every 6 months were clinically and functionally stable and outcomes were well maintained, as evidenced by the stable PANSS, CGI-S, and PSP scores over the 3-year period. No new safety concerns outside the adverse event profile of the drug were identified, and no deaths were reported. Directional improvements within subgroup analyses by various baseline demographic and disease characteristics did not deviate from the overall findings. Overall, the 3-year adverse event profile of PP every 6 months was consistent with the known profile of PP. Notably, the frequency of TEAEs leading to drug withdrawal in this study of PP every 6 months (5.0%) was similar to those reported in a noninferiority study of PP every 3 months (48-week double-blind study: 3.0%) and PP monthly (17-week open-label study: 4.2%; 48-week double-blind study: 2.5%).15

While not all patients may respond to LAI antipsychotics,26 they are some of the most effective treatments for schizophrenia in adults and are underused in clinical practice.6,11 Reasons for underuse include clinician preference for oral medications in early treatment, a lack of discussion about LAI antipsychotics between patients and health care practitioners, assumption of patients’ negative perceptions or refusal of LAIs, clinician overestimation of medication adherence, and limited support for staff with expertise to administer injections.6,11,27,28 However, compared with oral antipsychotics, LAI antipsychotics are associated with a lower risk of relapse and rehospitalization, treatment discontinuation, work disability, and mortality.2,29,30,31 Such evidence suggests that schizophrenia-related outcomes could improve with increased use of LAI antipsychotics.31 Consensus reached by a recent Delphi panel regarding LAI antipsychotics use in early-phase schizophrenia aligns with this suggestion, recommending that all patients should be evaluated for potential suitability for LAI treatment.32 The panel also agreed that the use of LAIs increases medication adherence and reduces treatment burden and functional decline, thereby promoting functional recovery.32 Although the definition of functional recovery is complex, recent studies have stressed the importance of factors influencing life engagement and quality of life, such as cognition, personal autonomy, professional activity, social relationships or support, and environmental factors.32,33,34,35 The longer dosing intervals associated with LAI antipsychotics contribute to clinical stability, providing potential for long-term improvements in functionality, social integration, and patient empowerment.36,37 Furthermore, LAI antipsychotic treatment in combination with nonpsychopharmacologic treatment strategies may encourage personal recovery beyond the framework of traditional outcome measures and mental health services.

Recovery, the combination of symptomatic remission and adequate psychosocial and educational or vocational functioning,38,39,40,41 is an established goal of treatment in adults with schizophrenia and usually involves integration of pharmacologic and psychologic approaches.42,43 Although improvements are often measured through traditional methods, such as changes in PSP, PANSS, and CGI-S scale scores, recovery may also be assessed through other psychosocial outcome measures. For example, the San Francisco Adult Strengths and Needs Assessment score has tracked reductions in criminal behavior and improvements in spirituality among patients who switched from an oral antipsychotic medication to an LAI antipsychotic.44 Regardless of approach, psychosocial interventions paired with LAI antipsychotic treatment are associated with improved functioning.45 In this context, symptomatic stability and relapse prevention are important first steps on the path toward achieving and maintaining functional recovery. The low rate of relapse reported in this study highlights the important role that LAI antipsychotics have as a treatment that can facilitate and support the recovery process. In this regard, treatments such as PP every 6 months can play a potentially important role in long-term recovery in patients with schizophrenia.

Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when analyzing this study’s results. First, the study lacked a comparator group. However, the results presented align with those of network meta-analyses of LAI and oral antipsychotics in that LAI PP was associated with a low risk for relapse and hospitalization and with a large improvement in mean rating scale scores.31,46 Second, there was a potential for effects of confounding demographic factors on data stemming from the small number of countries participating in the OLE study. Third, patients who started PP every 6 months and experienced relapse, died, or withdrew from the double-blind trial (year 1) and those who did not opt into the OLE study (years 2 and 3) were not included in this analysis. Fourth, patients agreed to be part of a double-blind randomized trial in the beginning, potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings. Fifth, patients included in this study were clinically stable; thus, our results may not be generalizable to the broader study population. Sixth, this study focused on relapse prevention. While these findings are important, we recognize that functional recovery in areas such as work functioning and social determinants of health are also key aspects of remission. Future research should include a focus on person-centered care and overall wellness and test the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for the achievement of functional recovery in patients treated with an LAI vs oral antipsychotic over the long term. However, despite these limitations, few studies have followed patients initiating LAI antipsychotic treatment prospectively for such a long period.

Conclusions

In a 2-year OLE study of a 1-year randomized clinical trial, a high proportion (95.9%) of patients receiving PP once every 6 months remained relapse free for up to 3 years with no new safety concerns emerging and with high treatment persistence. The findings suggest that PP every 6 months, the first antipsychotic to date that can be administered effectively only twice per year, adds to the range of long-term treatment options for patients with schizophrenia.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. CGI-S Change From Baseline to Month 36 by Age

eTable 2. CGI-S Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Body Mass Index

eTable 3. CGI-S Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Duration of Illness

eTable 4. CGI-S Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Sex

eTable 5. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline to Month 36 by Age

eTable 6. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Body Mass Index

eTable 7. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Duration of Illness

eTable 8. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Sex

eTable 9. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Age

eTable 10. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Body Mass Index

eTable 11. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Duration of Illness

eTable 12. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Sex

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Schizophrenia. January 10, 2022. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia

- 2.Rubio JM, Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, Kane JM, Tiihonen J. Long-term continuity of antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia: a nationwide study. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(6):1611-1620. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbab063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granström O, De Hert M. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(4):200-218. doi: 10.1177/2045125312474019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wander C. Schizophrenia: opportunities to improve outcomes and reduce economic burden through managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(3)(suppl):S62-S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kinney K, et al. Real-world outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):554-561. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correll CU, Lauriello J. Using long-acting injectable antipsychotics to enhance the potential for recovery in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):MS19053AH5C. doi: 10.4088/JCP.MS19053AH5C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najarian D, Sanga P, Wang S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, noninferiority study comparing paliperidone palmitate 6-month versus the 3-month long-acting injectable in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25(3):238-251. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyab071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostuzzi G, Bertolini F, Del Giovane C, et al. Maintenance treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics for people with nonaffective psychoses: a network meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(5):424-436. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20071120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brissos S, Veguilla MR, Taylor D, Balanzá-Martinez V. The role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a critical appraisal. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(5):198-219. doi: 10.1177/2045125314540297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alphs L, Mao L, Lynn Starr H, Benson C. A pragmatic analysis comparing once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus daily oral antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2-3):259-264. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1-24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15032su1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Højlund M, Correll CU. Switching to long-acting injectable antipsychotics: pharmacological considerations and practical approaches. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24(13):1463-1489. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2023.2228686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59. doi: 10.1007/s40263-020-00779-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):830-839. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savitz AJ, Xu H, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation for patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, noninferiority study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(7):pyw018. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Najarian D, Turkoz I, Knight RK, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of paliperidone 6-month formulation: an open-label 2-year extension of a 1-year double-blind study in adult participants with schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26(8):537-544. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyad028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M, Hough D. A 52-week open-label study of the safety and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):685-697. doi: 10.1177/0269881110372817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(2-3):107-117. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathews M, Gopal S, Nuamah I, et al. Clinical relevance of paliperidone palmitate 3-monthly in treating schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1365-1379. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S197225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.INVEGA SUSTENNA (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use. Highlights of prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; July 2022.

- 21.INVEGA TRINZA (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use. Highlights of prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; August 2021.

- 22.INVEGA HAFYERA (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for gluteal intramuscular use. Highlights of prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; August 2021.

- 23.Takács P, Kunovszki P, Timtschenko V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of second generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics based on nationwide database research in Hungary: an update. Schizoph Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgac013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Fond G, Falissard B, Nuss P, et al. How can we improve the care of patients with schizophrenia in the real-world? a population-based cohort study of 456 003 patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(12):5328-5336. doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-02154-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio JM, Schoretsanitis G, John M, et al. Psychosis relapse during treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):749-761. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30264-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane JM, Correll CU. Optimizing treatment choices to improve adherence and outcomes in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):IN18031AH1C. doi: 10.4088/JCP.IN18031AH1C [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Kane JM, McEvoy JP, Correll CU, Llorca PM. Controversies surrounding the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(11):1189-1205. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00861-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):686-693. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solmi M, Taipale H, Holm M, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic use for reducing risk of work disability: results from a within-subject analysis of a Swedish national cohort of 21 551 patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(12):938-946. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.21121189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):387-404. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arango C, Fagiolini A, Gorwood P, et al. Delphi panel to obtain clinical consensus about using long-acting injectable antipsychotics to treat first-episode and early-phase schizophrenia: treatment goals and approaches to functional recovery. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):453. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-04928-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roosenschoon BJ, Kamperman AM, Deen ML, Weeghel JV, Mulder CL. Determinants of clinical, functional and personal recovery for people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses: a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahera G, Gálvez JL, Sánchez P, et al. Functional recovery in patients with schizophrenia: recommendations from a panel of experts. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1755-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Correll CU, Ismail Z, McIntyre RS, Rafeyan R, Thase ME. Patient functioning and life engagement: unmet needs in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(4):LU21112AH1. doi: 10.4088/JCP.LU21112AH1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Giron-Hernandez C, Han JH, Alberio R, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate 6-month versus paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injectable in European patients with schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis of a global phase-3 double-blind randomized non-inferiority study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023;19:895-906. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S400342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Portilla MP, Benito Ruiz A, Gómez Robina F, García Dorado M, López Rengel PM. Impact on functionality of the paliperidone palmitate three-month formulation in patients with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia: a real-world observational prospective study. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022;23(5):629-638. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2021.2023496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correll CU, Kishimoto T, Nielsen J, Kane JM. Quantifying clinical relevance in the treatment of schizophrenia. Clin Ther. 2011;33(12):B16-B39. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296-1306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen HG, Speyer H, Starzer M, et al. Clinical recovery among individuals with a first-episode schizophrenia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49(2):297-308. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbac103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carbon M, Correll CU. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(4):505-524. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.4/mcarbon [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phahladira L, Luckhoff HK, Asmal L, et al. Early recovery in the first 24 months of treatment in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. NPJ Schizophr. 2020;6(1):2. doi: 10.1038/s41537-019-0091-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrivastava A, Johnston M, Shah N, Bureau Y. Redefining outcome measures in schizophrenia: integrating social and clinical parameters. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(2):120-126. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336662e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshimatsu K, Elser A, Thomas M, et al. Recovery-oriented outcomes associated with long-acting injectable antipsychotics in an urban safety-net population. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(6):979-982. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00412-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Ramirez LF, et al. Prospective trial of customized adherence enhancement plus long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication in homeless or recently homeless individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):1249-1255. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ostuzzi G, Bertolini F, Tedeschi F, et al. Oral and long-acting antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a network meta-analysis of 92 randomized trials including 22 645 participants. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):295-307. doi: 10.1002/wps.20972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. CGI-S Change From Baseline to Month 36 by Age

eTable 2. CGI-S Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Body Mass Index

eTable 3. CGI-S Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Duration of Illness

eTable 4. CGI-S Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Sex

eTable 5. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline to Month 36 by Age

eTable 6. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Body Mass Index

eTable 7. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Duration of Illness

eTable 8. PANSS Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Sex

eTable 9. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Age

eTable 10. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Body Mass Index

eTable 11. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Duration of Illness

eTable 12. PSP Total Score Change From Baseline at Each Visit by Sex

Data Sharing Statement