In many countries people are struggling to set up good ways of eliciting the views of patients. In England, the model of citizens' juries has been pursued. In Canada, dialogue sessions with members of the public have been used to reframe the healthcare contract

The legitimacy and sustainability of any major policy decision increasingly depends on how well it reflects the underlying values of the public.1,2 Experts and stakeholders provide essential technical input but their role is distinct from that of the citizen and cannot replace it. As governments ponder difficult and at times unpalatable choices on health care, policy needs to be informed by ordinary “unorganised” citizens, as well as powerful “organised” interest groups.

The Romanow Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada adopted an innovative approach to eliciting the views of “unorganised” citizens using the “ChoiceWork dialogue” method created by Viewpoint Learning, based on the research by its chairman, Daniel Yankelovich.3,4 This entailed a full day of dialogue with representative cross sections of the Canadian population. This article gives a brief description of the process, the outcome, and the effects to date.5

Summary points

Citizens' values should define the boundaries of action in a democracy

The Romanow Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada opted for a “ChoiceWork dialogue,” wherein representative groups of ordinary “unorganised” citizens work through complex issues and make value based choices

Combining their roles as patients, taxpayers, and members of the community, participants reframed the healthcare contract, redefining both individual and collective responsibilities. This had an important impact on the commission's report and the ensuing debate

Such engagement of the public is more costly than polling, but it is essential when opinions are unstable and difficult decisions must be made

The process

ChoiceWork dialogues engage members of the public on important issues before decisions are made. The method is particularly valuable on issues where changed circumstances create new challenges (such as health care) that have to be recognised and considered. Under these conditions people's spontaneous opinions are highly unstable and misleading.

The key insight behind this method is that the public needs the opportunity to “work through” conflicting values and difficult choices in order to reach judgments on an important issue. Working through depends on dialogue: it cannot be accomplished through traditional, one way public education. ChoiceWork dialogues accelerate this process.6

Twelve dialogue sessions were held across Canada, each with about 40 citizen participants (n=489) randomly selected to provide a representative cross section of the Canadian population. Participants had to be English speaking or French speaking citizens aged 18 years and over. People working in the healthcare system were excluded. The dialogues were facilitated by teams of two professional facilitators specially trained for the project, who followed a standard format. The steps in the project and the agenda for the day are set out in box B1.

Box 1.

Basic steps in a ChoiceWork dialogue project

- Research (using polls and other sources) to provide a baseline reading on what stage of development public opinion has reached

- Identification of critical choices and scenarios and preparation of the workbook

- A series of one day dialogue sessions with representative cross sections of the public. A typical one day session includes the following:

- Predialogue reading of the workbook as participants arrive

- Initial orientation by the professional facilitators (including the purpose of the dialogue and the use to be made of the results, ground-rules for the session, introduction of some basic facts—in this case, about health care in Canada)

- Introduction of the chosen scenarios on the focal issue

- Completion of predialogue questionnaire to measure participants' initial views

- Opening comments from each participant to identify key concerns about the future of health care

- Dialogue among participants (in smaller self facilitated groups and then in a professionally facilitated plenary session) to assess the results likely to follow from each choice, and then to define their recommendations

- Completion of a post-dialogue questionnaire designed to measure how and why views have changed in the course of the day

- Concluding comments from each participant on how their views changed and their final message to decision makers

- Quantitative and qualitative analysis of how and why people's positions evolved during the dialogues

- A report to participants and to decision makers

As a starting point, participants were asked to consider four scenarios for reform of health services (box B2). Each has at its core a process under active discussion in Canada today. The scenarios were developed through intensive discussions with staff from the commission and with various experts in health care, and informed by a review of 20 years of opinion research7; the scenarios were presented in a workbook using a tested format that included relevant background and arguments for and against each reform scenario.

Box 2.

Four scenarios for the future of health care in Canada

Participants were asked to accomplish two major tasks during the day: firstly, to create their own vision of the health care system they would like to see in 10 years' time; secondly, to work through the practical choices and trade offs required to realise that vision—working firstly in self facilitated groups to ensure that the conclusions reached would be their own. They then worked in a plenary session in which the facilitators prompted them to identify the key similarities and differences among the groups' reports, and to further define the areas of common ground.

Next, the participants spent almost five hours working through the trade offs and choices their vision required, again firstly in self facilitated groups and then in plenary session. In the plenary session the facilitators used prompts to underline the key trade offs that participants needed to consider. These prompts were based on the patterns that had emerged in the first two dialogue sessions. The outcomes—remarkably consistent across the 12 dialogues—have since been confirmed through a follow up telephone survey of a representative sample of 1600 Canadians.8

The outcome

At first many of the participants hoped that the system could be “fixed” by eliminating waste and improving efficiency. When that hope faded, the focus shifted to renewing the system through reforms consistent with the participants' values: access based on need, fairness, and efficiency. As they heard their own values strongly reinforced by others in the room, a strong sense of solidarity emerged.

The potential in having a team of medical professionals (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and others) to provide primary care that is both more coordinated and also supported by a central information system was appreciated. To make such a system work, participants were willing to change the way they use the system: to sign up with a provider team for one year (primary care in Canada is based mainly on solopractitioners), to see a nurse for routine care, and to have their personal medical information placed on an electronic record (smart card).

Even with these changes, participants came to realise that more funding would be required to sustain the healthcare system. They chose not to turn to a parallel private system, on the grounds that it would drain valuable resources away from the public system. They decided that user fees for basic hospital and medical services would discourage people who are less well off from seeking needed care. Finally, they turned to public funding. When they could not agree on reallocations from other programmes such as education, they turned to tax increases as the only viable choice, but only under stringent conditions:

Taxes must be earmarked to ensure the money is spent on health care;

There must be an independent “auditor general” for health to document value for money and assess performance against other provinces or countries;

Greater efficiency and cooperation within provincial systems and between provincial and federal governments and clearer definition of which is responsible for what so that they can be held to account.

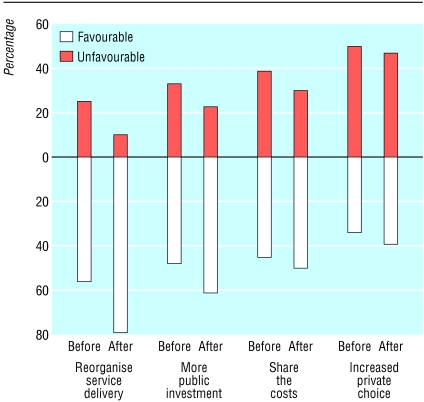

By the end of the day, change was much more acceptable (figure). An extraordinary 79% (range 76-91%) of participants—up from 56% (39-64%) at the beginning of the day—were in favour of reorganising service delivery in provider networks. Support for adding more resources through tax increases increased from 48% to 61% (range 30-41% and 62-79%, respectively).

The new healthcare contract that emerged is anchored by the traditional social values of a healthcare scheme provided by the state—universal coverage and access based on need—while adding new economic values of efficiency and accountability.

The impact

The cost of the dialogues was significant ($C1.3 million) but the results had a marked influence on the commission's report released in November 2002 and on the debate that has ensued. Other efforts to consult with Canadians about health care had concluded that the public was unable to make trade offs.9 In this dialogue, not only were choices made but trade offs that have been considered unworkable in Canadian healthcare policy were accepted. For instance, elite groups in Canada generally believe that Canadians

Will not sign up with a primary care network

Will reject having their personal information on an electronic health record

Do not care about health education and prevention

Have no useful views on governance.

Participants in all the dialogues contradicted these preconceptions. And they were elated and empowered by experiencing the dialogue (box B3). It was remarkable how quickly participants in all the dialogues absorbed complicated information, learning from each other and the workbook, and applied this knowledge to make difficult choices. One important lesson is that the abilities (and desire) of the general public to engage in this way should not be underestimated.10

Box 3.

Participants' own words (extracted from session videotapes)

Commissioner Romanow responded in two different ways in his final report Building on Values.11 Firstly, the report redefined the role of the citizen, from passive consumer of healthcare services to active participant in the governance of the health system. The principles of public participation and mutual responsibility were entrenched in a proposed health “covenant” between governments, providers, and the Canadian public. And the report recommended regular reruns of the dialogues.

Secondly, and more importantly, the report echoed the demand of participants for transparency and accountability, for a new, more open policy process based on regular and comprehensive reviews of achievements and results attained by public authorities. This recommendation has since been taken up by the public and with stakeholder groups to a degree that shows that the dialogue has tapped a powerful new political dynamic.

Finally, the dialogue has heightened political interest in this kind of engagement. Decision makers recognise that they are hearing a different voice, a true voice of the public. They also know that the legitimacy of their policy decisions will depend on how well that voice has been heard and understood.

Figure.

Views on four scenarios for the future of health care in Canada, rated before and after ChoiceWork dialogues in 12 sessions. Participants were asked to rate each scenario on its merits, not to pick their favourite. On a seven point rating scale, scores of 5-7 were favourable and 1-3 unfavourable; scores of 4 (“undecided”) are not recorded5

Footnotes

Funding: The dialogue was funded by the Commission on the Future of Health in Canada

Competing interests: SR is the president of Viewpoint Learning, a company which organises ChoiceWork dialogues as one line of business. P-GF was the director of research of the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

References

- 1.Maxwell J. Toward a common citizenship: Canada's social and economic choices. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Network; 2001. www.cprn.org/cprn.html . (CPRN reflexion paper No 4.) www.cprn.org/cprn.html (accessed 31 Mar 2003). (accessed 31 Mar 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosell S. Renewing governance. Toronto: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yankelovich D. Coming to public judgment. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yankelovich D. The magic of dialogue. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell J, Jackson K, Legowski B, Rosell S, Yankelovich D, Forest PG, et al. Report on citizens' dialogue on the future of health care in Canada. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. www.cprn.org/cprn.html (accessed 31 Mar 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosell S. Changing frames. La Jolla, CA: Viewpoint Learning; 2000. www.viewpointlearning.com/leadership.html (accessed 31 Mar 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendelsohn M. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2001. Canadians' thoughts on their health care system: preserving the Canadian model through innovation.www.healthcarecommission.ca (accessed 31 Mar 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Future of health care in Canada: general public survey. Final Report (March 2002). Ottawa: Ekos Research Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Forum on Health. Canada health action: building the legacy. Vol. 2. Ottawa: National Forum on Health; 1997. . (Values Group synthesis report.) [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med (in press). Available on www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02779536. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Final report. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. www.healthcarecommission.ca (accessed 31Mar 2003). [Google Scholar]