Abstract

Ureaplasma parvum, a member of the Mollicutes class, is a rare but significant pathogen in extragenital infections. This case report is the tenth known case of Ureaplasma spp. peritonitis, occurring in a 36-year-old female post extensive surgery for metastatic sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma. Following the intervention, the patient exhibited post-surgical peritonitis with fever despite empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics. Conventional bacterial and fungal cultures remained negative, prompting the use of 16 S rRNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for diagnosis. Ureaplasma parvum was detected in both peritoneal and perihepatic fluid samples, and in the urine, leading to the initiation of doxycycline therapy. The patient responded positively to the treatment, with complete resolution of symptoms and no recurrence observed during a four-year follow-up. This report underscores the clinical challenge posed by Ureaplasma spp. due to its resistance to common antibiotics and difficulty in cultivation. It highlights the importance of molecular diagnostics in identifying such pathogens in culture-negative cases and the necessity of considering Ureaplasma spp. especially in female patients with persistent peritonitis post-urogenital procedures or surgeries. The case also reflects on the limited data regarding antimicrobial susceptibility, emphasizing the need for tailored therapeutic approaches based on local resistance patterns and the clinical context. Ultimately, this case contributes valuable insights into the diagnosis and management of Ureaplasma spp. peritonitis, advocating for heightened clinical suspicion and appropriate molecular testing to ensure effective patient outcomes.

Keywords: Ureaplasma, Peritonitis, Treatment, 16S rRNA

Introduction

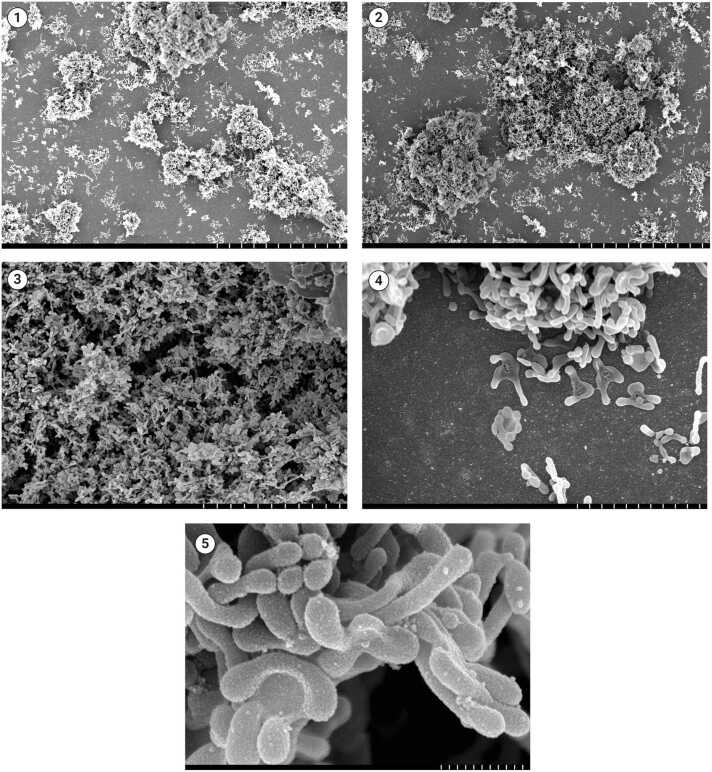

Ureaplasmas represent a group of ubiquitous self-replicating bacteria belonging to the class Mollicutes and are among the smallest known free-living organisms with the unique ability to metabolize urea as a source of energy [1], [2] (Fig. 1). Clinically relevant species include Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum, which are part of the human microbiota and can be isolated from both female and male genital tracts, with varying frequencies, often correlating with sexual activity [3]. These organisms primarily cause urogenital tract infections, such as non-gonococcal urethritis, and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including chorioamnionitis and premature rupture of membranes [4], [5]. They are rarely implicated in extragenital infections, such as septic arthritis [6], infective endocarditis [7], [8], osteomyelitis [7], [9], sternal wound infections [10] and peritonitis [11], [12], [13], [14].

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron micrographs showing aggregates of Ureaplasma spp. colonies forming biofilms with self-produced matrix components at different magnifications (picture 1, 30 µm; picture 2, 30 µm; picture 3, 10 µm; picture 4, 3 µm; picture 5, 500 nm. Courtesy of Derek Fleming, PhD – Division of Clinical Microbiology, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA).

The treatment of infections caused by Ureaplasma spp. is complicated by the lack of a peptidoglycan cell wall and their inability to synthesize folic acid, which confers intrinsic resistance to β-lactams and other cell wall-targeting agents, as well as to sulfonamides and trimethoprim [4], [5]. They require complex growth media for cultivation, such as A8 agar or 10B broth; hence, diagnosis and susceptibility testing can be challenging, as routine bacterial cultures often fail to isolate these organisms [15]. Diagnosing extragenital infection requires a high index of suspicion and is often established through molecular testing, such as 16 S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

In this report, we describe a case of peritonitis caused by Ureaplasma parvum in a patient following extensive surgery for sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma. To our knowledge, this is the tenth case of Ureaplasma spp. peritonitis reported in the literature.

Case report

The patient is a 36-year-old woman with a history of metastatic, moderately differentiated sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma that had spread to the liver, omentum, spleen, and bilateral ovaries. She had previously completed ten cycles of a combination chemotherapy regimen consisting of folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX), and bevacizumab. She was admitted to our facility for a complex surgical intervention, which included liver wedge resection, left colectomy with primary anastomosis, splenectomy, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, intra-abdominal debulking, and bilateral ureteral stent placement.

On the first postoperative day, she had multiple low-grade febrile episodes (38.2 °C). Physical examination revealed minimal wound dehiscence and diffuse abdominal tenderness on superficial and deep palpation without guarding. Vital signs showed a blood pressure of 119/83 mmHg, a heart rate of 113 beats/min, and an oxygen saturation of 97 % on room air. Laboratory tests showed a total white blood cell (WBC) count of 16.8 × 109/L (reference range 3.4–9.6 ×109/L), a lactic acid level of 1.0 mmol/L (reference range 0.5–2.2 mmol/L), a hemoglobin level of 8.9 g/dL (reference range 13.2–16.6 g/dL), and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 238 mg/dL (reference range ≤ 8.0 mg/L). Levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and total bilirubin were within normal limits. Two sets of peripheral blood cultures were obtained. Urinalysis revealed 1–3 WBCs per high-power field with no bacteria seen on microscopy.

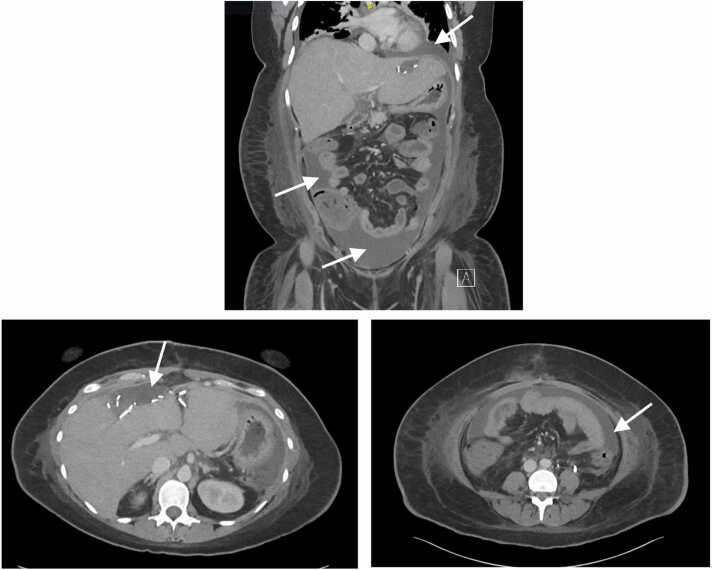

At this stage, the differential diagnosis was broad. However, intravenous (IV) piperacillin/tazobactam was started empirically due to concerns for a complicated healthcare-associated intra-abdominal infection, given the extensive nature of the surgery. On postoperative day seven, the patient's fever recurred, peaking at 39.1 °C, despite ongoing antibiotic therapy, and her white blood cell (WBC) count increased to 24.4 × 109/L An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained with results shown in Fig. 2. A 12 French catheter was placed into the superior hepatic fluid collection. Additionally, paracentesis was performed with aspiration of 190 mL of serous fluid. Ascitic fluid analysis showed 6809 nucleated cells/mL, 83 % of which were neutrophils. No malignant cells were observed on cytological examination. The ascitic fluid creatinine (Cr) was 1.50 mg/dL (serum Cr 1.53 mg/dL), making a urinary leakless likely. Fluid from both sites was sent for fungal and bacterial cultures. She was noted to have new onset post-operative diarrhea; therefore, Clostridioides difficile stool PCR was obtained and returned negative. The antimicrobial regimen was empirically broadened to include IV caspofungin and IV vancomycin, but there was no clinical response after 72 h, and she continued to have high-grade fevers.

Fig. 2.

CT scans showing abdominal ascites (white arrows), with a large fluid collection in the left upper quadrant surrounding the stomach and anterior pelvis (coronal plane, upper; axial plane lower right) in addition to an anterior loculated perihepatic fluid collection (axial plane, lower left).

Blood and abdominal fluid fungal and bacterial cultures remained negative. The differential diagnosis at that time was expanded to include post-surgical intra-abdominal infection involving common gastrointestinal pathogens but without adequate source control; post-surgical intra-abdominal infection caused by atypical and/or fastidious pathogens, including Mycobacteria spp, Trichomonads, Mycoplasma spp.; or non-infectious causes such as drug-induced fever. Subsequently, 16 S rRNA PCR was performed on stored peritoneal and perihepatic fluid samples, and the results were positive for Ureaplasma parvum in both samples. For completion, a urine sample was sent for in-house PCR testing and returned positive results for Ureaplasma parvum but negative for Ureaplasma urealyticum, while a blood sample PCR was negative for both. The organisms failed to grow in specialized cultures for susceptibility testing.

Doxycycline (100 mg orally twice daily) was initiated, resulting in a gradual resolution of the fever and a progressive decrease in WBC count. Piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin, and caspofungin were discontinued, and the abdominal drain was removed following serial CT scans and sinograms confirming the resolution of the perihepatic fluid collection. The patient completed an extended eight-week course of doxycycline, concurrent with chemotherapy, with complete resolution of her symptoms and no evidence of recurrence after one year of follow-up.

Discussion

Ureaplasma spp. peritonitis is an emerging clinical challenge, with documented cases primarily affecting females, often following surgical or urogenital manipulation. Nine cases of Ureaplasma spp. peritonitis have been reported in the literature to our best knowledge (Table 1). All patients were women, and their median age was 35 years (range 28–50 years). Seven patients (70 %) were on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), with Ureaplasma likely gaining access to the peritoneum through the fallopian tubes [14]. The remaining infections, including our case, mainly occurred following surgery and/or manipulation of the urogenital tract in cases of oocyte retrieval for in vitro fertilization, or IUD insertion. We excluded one case of U. parvum ventriculitis related to ovarian cyst marsupialization, adhesiolysis and ventricular peritoneal drainage repositioning weeks after a polymicrobial peritonitis due to bladder rupture treated with laparotomy and I.V. vancomycin in a 18-year-old female with congenital myelomeningocele and hydrocephalus [16]. In fact, even if the abdominal clinical picture might be compatible with Ureaplasma infection, there was no direct isolation from peritoneal fluid of Ureaplasma spp. with conventional or molecular microbiological techniques and the authors stated that the source of ventriculitis was uncertain.

Table 1.

Ten cases of peritonitis caused by Ureaplasma spp.

| Case number | Age/ ASAB |

Clinical presentation | Underlying condition/ risk factors | Organism | Source | Peritoneal fluid analysis | Identification method | Susceptibility testing | Concurrent organisms | Treatment | Duration | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34/F | Peritonitis No improvement on empiric cefixime |

Ultrasound guided oocyte retrieval for in vitro fertilization | Ureaplasma parvum | Fluid from retrouterine pelvic collection | NR | Culture, real-time PCR | Susceptible to tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones | None | Surgical drainage of the abscess Ticarcillin/clavulanic acid I.V. and ciprofloxacin I.V. Transitioned to a P.O. regimen |

3 weeks | Complete resolution of symptoms | [11] |

| 2 | 45/F | Peritonitis Purulent abdominal wall drainage at the laparotomy site |

Emergency liver transplantation due to fulminant hepatic failure |

Ureaplasma urealyticum Mycoplasma hominis |

Swabs from the abdominal cavity and abdominal wall | NR | Culture | NR | None | Multiple laparotomies Ciprofloxacin I.V. |

3 days* | Resolution of the peritonitis | [12] |

| 3 | 50/F | Recurrent peritonitis Clinical response to empiric IP tobramycin and oral ciprofloxacin followed by relapse |

PKD ESRD on CAPD Sexual intercourse 10 h prior to most recent peritonitis episode |

Ureaplasma urealyticum | Peritoneal fluid Vaginal canal swab |

NR | Culture | NR | None | I.P. erythromycin Doxycycline P.O. Vaginal demeclocycline |

10 days | Resolution of the peritonitis with no relapse | [13] |

| 4 | 28/F | Recurrent peritonitis No improvement with IP vancomycin |

Lupus nephritis ESRD on CAPD |

Ureaplasma urealyticum | Peritoneal fluid | 1611 WBC/µL (76 % N) | 16 S rRNA PCR | NR | None | Removal of the CAPD catheter Doxycycline P.O. |

2 weeks | Resolution of the peritonitis with no relapse | [14] |

| 5 | 32/F | Recurrent peritonitis Clinical response to empiric ciprofloxacin therapy followed by relapse |

Lupus nephritis ESRD on CAPD Menorrhagia, prompting IUD insertion |

Ureaplasma urealyticum | Peritoneal fluid | NR | 16 S rRNA PCR | NR | None | Removal of the CAPD catheter Removal of the IUD followed by Doxycycline P.O. |

10 days | Multiple relapses following empiric ciprofloxacin Resolution of the peritonitis after IUD removal and P.O. doxycycline |

[17] |

| 6 | 50/F | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis treated with I.V. ceftazidime and cefazolin, then vancomycin and levofloxacin. | Proliferative sclerosing glomerulonephritis ESRD on CAPD |

Ureaplasma parvum | Peritoneal fluid | 1425 WBC/µL on admission, then 37µLbefore targeted antibiotic | mNGS | Not reported | None | Clarithromycin P.O. | 2 weeks | Complete symptom resolution | [18] |

| 7 | 35/F | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis treated with IP cefazolin, vancomycin, meropenem, tigecycline | Immunoglobulin A nephropathy ESRD on CAPD |

Ureaplasma parvum | Peritoneal fluid | NR | mNGS Culture of vaginal secretions^ |

Not reported | None | IP and P.O. azithromycin, IP tigecycline | 14 days | Complete symptom resolution | [19] |

| 8 | 35/F | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis treated with IP cefazolin, vancomycin, meropenem | Lupus nephritis ESRD on CAPD |

Ureaplasma parvum | Peritoneal fluid | NR | mNGS | Not reported | None | IP and oral azithromycin | 11 days | Complete symptom resolution | [19] |

| 9 | 42/F | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis treated with IP cefazolin, vancomycin, meropenem, tigecycline | Chronic renal failure ESRD on CAPD |

Ureaplasma parvum | Peritoneal fluid | NR | mNGS Culture of vaginal secretions^ |

Not reported | None | IP tigecycline and oral minocycline (stopped for adverse event) | 2 weeks | Complete symptom resolution | [19] |

| 10 | 36/F | Postoperative peritonitis treated with no improvement on vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam and caspofungin | Sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma with distant metastasis to liver, omentum, spleen and bilateral ovaries. Liver wedge resection, left colectomy with primary anastomosis, splenectomy, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, intra-abdominal debulking, and bilateral ureteral stent placement. |

Ureaplasma parvum | Peritoneal and perihepatic fluids Urine |

6809 WBC µL, 83 % N | 16 s rRNA PCR and in-house PCR | Unsuccessful growth on cultures | None | Drainage of abdominal fluid collection Doxycycline PO |

8 weeks | Complete symptom resolution | PR |

^ The authors specified that Mycoplasma culture of vaginal secretions does not distinguish U. urealyticum from U. parvum.

Abbreviations: 16 s rRNA PCR, 16 s ribosomal RNA polymerase chain reaction; ASAB, assigned sex at birth; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; F, female; IP, intraperitoneal; IUD, intrauterine device; M, male; mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing; N, neutrophils; NR, not reported; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; P.O., oral; PR, present report; WBC, white blood cells.

The total duration of therapy is unclear. Pathogens were eliminated based on serial cultures after 3 days of treatment.

All patients presented with clinical features suggestive of acute peritonitis, such as fever, varying degrees of abdominal tenderness and pain, purulent drainage, ascites, high leukocyte and CRP levels, and abnormal peritoneal fluid analysis. Some cases (cases 2, 3, 4, and 5) developed recurrence of symptoms, and many required multiple invasive procedures before establishing a microbiological diagnosis, emphasizing the stubborn and elusive nature of these infections. The majority of patients had chronic renal diseases requiring renal replacement therapy. Specifically, lupus nephritis in young women was the primary indication for CAPD in 3 out of 7 patients (42.8 %) (cases 4, 5, 8). Only two patients were immunocompromised (20 %) (cases 2 and 10), highlighting that, unlike other forms of extragenital manifestations, the main risk factor for Ureaplasma spp peritonitis appears to be urogenital manipulation or bacterial translocation in colonized female patients.

Of the ten cases, U. parvum was isolated in six (60 %) (cases 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10), while U. urealyticum in three (30 %) (cases 3, 4, and 5). In one patient, Mycoplasma hominis and U. urealyticum coinfection were observed (case 2). Diagnosis was made using conventional cultures alone in two patients (cases 2 and 3), while molecular testing was positive as a standalone test in five patients (cases 4, 5, 6, 8, 10). Specifically, 16 S rRNA PCR was used in three cases (cases 4, 5, and 10), whereas metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) was used in two patients (cases 6 and 8). Three patients had a concomitant diagnosis using culture and molecular methods (cases 1, 7 and 9).

The median duration of antibiotic therapy in the reported cases was 14 days (range 3 – 56 days). In our patient, doxycycline was continued concurrently with chemotherapy to minimize the risk of relapse or treatment failure, accounting for the prolonged course. Oral tetracyclines were the most commonly used drugs (4/10, 40 %), followed by macrolides (3/10, 30 %), fluoroquinolones (2/10, 20 %), and minocycline (1/10, 10 %). Procedures aimed at source control were performed in 5/10 (50 %) patients, with catheter removal in patients with CAPD being the most common. The overall outcome was positive for all patients, with no recurrences observed after definitive treatment.

Complicated intra-abdominal infections are a significant cause of infection-related mortality in the intensive care unit, with mortality rates ranging from 22 % to 55 % in cases of generalized post-operative peritonitis [20], [21]. Management typically involves achieving adequate source control through the drainage of infected foci, surgical management of peritoneal contamination, and the administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, often targeting enteric organisms [20]. In hospitalized patients with peritonitis, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and macrolides — the agents of choice for treating infections caused by Ureaplasma spp — are rarely used as empirical regimens [14]. This underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion, particularly in patients with culture-negative peritonitis who do not respond to broad-spectrum antibiotics and in patients with a history of recent urogenital manipulations or intra-abdominal surgical interventions.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was not performed in our case due to the failure to isolate the organism by conventional cultures. Data regarding the antimicrobial susceptibility of Ureaplasma spp., is limited. Inconsistencies arise from variability in interpretative criteria, coupled with challenges in the cultivation and performance of broth microdilution [5], [22]. In some regions, such as South Africa, resistance rates of Ureaplasma spp to first-line drugs are high, significantly limiting treatment options [23]. In the United States, recent reports have identified levofloxacin resistance rates of 6.4 % and 5.2 % and a proportion of isolates showing ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥ 4 μg/mL for 27.2 % and 68.8 % in U. parvum and U. urealyticum, respectively, with no detected macrolide resistance. Only a single U. parvum isolate was resistant to tetracyclines, supporting the use of doxycycline in this context [5]. Variable resistance patterns to fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and tetracyclines have been reported in France, the UK, and Italy [24], [25], [26]. Therefore, when Ureaplasma spp. infection is suspected, clinicians should initially send specimens for molecular testing to establish a rapid diagnosis. This should ideally be followed by sending specimens to a especialized referral center for cultures and AST. When isolation of the organism is not possible, empiric mono- or combination therapy can be considered, depending on the local epidemiology, the clinical syndrome, and the overall status of the patient.

In conclusion, Ureaplasma spp infection should be considered in patients with culture-negative peritonitis who do not improve with broad-spectrum antibiotics, particularly young women following invasive urogenital procedures. Understanding local resistance patterns and isolating the organism for susceptibility testing, along with interventions aimed at source control are essential for successful treatment. The difficulty in cultivating Ureaplasma spp. highlights the importance of molecular diagnostics, such as 16 S rRNA PCR, in identifying these pathogens.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Statement

A research authorization was signed by the patient allowing for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Francesco Petri: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. Fady Gemayel: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. Said El Zein: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Aaron J. Tande: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Matthew J. Thoendel: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Elie F. Berbari: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Derek Fleming, PhD, for providing interesting scanning electron micrographs of Ureaplasma spp., Rita Igwilo-Alaneme, MBBS, for useful clinical insights, Omar Mahmoud, MD, for his help in reviewing the paper, and Ellen M Aaronson, M.S., AHIP for her help in conducting the literature search.

Contributor Information

Francesco Petri, Email: francescopetri2@gmail.com.

Elie F. Berbari, Email: berbari.elie@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Sweet R.L., Gibbs R.S. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins,; 2012. Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitman W.B., Rainey F., Kämpfer P., Trujillo M., Chun J., DeVos P., et al. Wiley Online Library,; 2015. Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormack W.M., Rosner B., Alpert S., Evrard J.R., Crockett V.A., Zinner S.H. Vaginal colonization with mycoplasma hominis and ureaplasma urealyticum. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13(2):67–70. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beeton M.L., Payne M.S., Jones L. The Role of Ureaplasma spp. in the Development of Nongonococcal Urethritis and Infertility among Men. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(4) doi: 10.1128/CMR.00137-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez J., Karau M.J., Cunningham S.A., Greenwood-Quaintance K.E., Patel R. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Clonality of Clinical Ureaplasma Isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(8):4793–4798. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00671-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George M.D., Cardenas A.M., Birnbaum B.K., Gluckman S.J. Ureaplasma septic arthritis in an immunosuppressed patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Clin Rheuma. 2015;21(4):221–224. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangogiannis N.G., Cate T.R. Endocarditis and Ureaplasma urealyticum osteomyelitis in a hypogammaglobulinemic patient. A case report and review of the literature. J Infect. 1998;37(2):181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)80174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korytny A., Nasser R., Geffen Y., Friedman T., Paul M., Ghanem-Zoubi N. Ureaplasma parvum causing life-threatening disease in a susceptible patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-220383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohiuddin A.A., Corren J., Harbeck R.J., Teague J.L., Volz M., Gelfand E.W. Ureaplasma urealyticum chronic osteomyelitis in a patient with hypogammaglobulinemia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87(1 Pt 1):104–107. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90219-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walkty A., Lo E., Manickam K., Alfa M., Xiao L., Waites K. Ureaplasma parvum as a cause of sternal wound infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1976–1978. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01849-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bébéar C., Grouthier V., Hocké C., Jimenez C., Papaxanthos A., Creux H. Ureaplasma parvum peritonitis after oocyte retrieval for in vitro fertilization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;172:138–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haller M., Forst H., Ruckdeschel G., Denecke H., Peter K. Peritonitis due to Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in a liver transplant recipient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10(3):172. doi: 10.1007/BF01964452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocca A.R., Esposto C., Utzeri G., Angeloni V., Capece R., Albanese E., et al. Two cases of ascending peritonitis in CAPD. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(2):242–243. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2009.00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yager J.E., Ford E.S., Boas Z.P., Haseley L.A., Cookson B.T., Sengupta D.J., et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis diagnosed by 16S rRNA gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(11):4310–4312. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01045-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CLSI . CLSI document M43-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute,; Wayne, PA: 2011. Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for Human Mycoplasmas; Approved Guideline. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saje A., Velnar T., Smrke B., Spazzapan P., Keše D., Kobal B., et al. Ureaplasma parvum ventriculitis related to surgery and ventricular peritoneal drainage. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26(5):513–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey E.A., Solomon L.R., Berry N., Cheesbrough J.S., Moore J.E., Jiru X., et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum CAPD peritonitis following insertion of an intrauterine device: diagnosis by eubacterial polymerase chain reaction. Perit Dial Int. 2002;22(3):422–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L., Nie Z., Zhao Y., Bao B. Peritonitis-associated with peritoneal dialysis following Ureaplasma parvum infection: A case report and literature review. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2023;45 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmmb.2023.100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C., Wang J., Yan J., Chen F., Zhang Y., Hu X. Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma parvum, and Ureaplasma urealyticum: hidden pathogens in peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;131:13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomkin J.S., Mazuski J.E., Bradley J.S., Rodvold K.A., Goldstein E.J.C., Baron E.J., et al. Diagnosis and Management of Complicated Intra-abdominal Infection in Adults and Children: Guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(2):133–164. doi: 10.1086/649554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulier S., Penninckx F., Verwaest C., Filez L., Aerts R., Fieuws S., et al. Factors affecting mortality in generalized postoperative peritonitis: multivariate analysis in 96 patients. World J Surg. 2003;27(4):379–384. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6705-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beeton M.L., Spiller O.B. Antibiotic resistance among Ureaplasma spp. isolates: cause for concern? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016:dkw425. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redelinghuys M.J., Ehlers M.M., Dreyer A.W., Lombaard H.A., Kock M.M. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Ureaplasma species and Mycoplasma hominis in pregnant women. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beeton M.L., Chalker V.J., Jones L.C., Maxwell N.C., Spiller O.B. Antibiotic resistance among clinical Ureaplasma isolates recovered from neonates in England and Wales between 2007 and 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(1):52–56. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00889-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meygret A., Le Roy C., Renaudin H., Bebear C., Pereyre S. Tetracycline and fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical Ureaplasma spp. and Mycoplasma hominis isolates in France between 2010 and 2015. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(10):2696–2703. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pignanelli S., Pulcrano G., Iula V.D., Zaccherini P., Testa A., Catania M.R. In vitro antimicrobial profile of U reaplasma urealyticum from genital tract of childbearing‐aged women in N orthern and S outhern I taly. Apmis. 2014;122(6):552–555. doi: 10.1111/apm.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]