Short abstract

Preventing fractures in elderly people is a priority, especially as it has been predicted that in 20 years almost a quarter of people in Europe will be aged over 65. This article describes the factors contributing to fracture, interventions to prevent fracture, and the various treatments.

Fractures in elderly people are an important public health issue, especially as incidence increases with age, and the population of elderly people is growing. Evidence based interventions do exist to prevent fractures, but they are not being applied.1,2 The challenges are to identify those most risk and to ensure that treatment is cost effective. Elderly people should be taught to improve their bone health and to reduce the risk of injury, but these measures are not restricted to this age group, as prevention should be throughout the life.3

Sources and methods

Recommendations are made following a comprehensive review of the literature, concentrating on systematic reviews and evidence based guidelines on fracture prevention that have been identified by a standardised search strategy as part of the European Bone and Joint Health Strategies Project. Priority was given to those systematic reviews and guidelines that met quality criteria, including criteria for guidelines from the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE).4

A universal problem

Around 310 000 fractures occur each year in elderly people in the United Kingdom. The cost of providing social care and support for these patients is £1.7b ($2.8b; €2.4b). Hip fractures place the greatest demand on resources and have the greatest impact on patients because of increased mortality, long term disability, and loss of independence. Although less common, vertebral fractures are also associated with long term morbidity and increased mortality.5 By 2025 it has been predicted that almost a quarter of the population in Europe will be aged over 65 years. The mean age of hip fracture in women is 81 years, and as the expected additional lifetime for an 80 year old women in England is 8.7 years, there is still a significant time for elderly women to benefit from fracture prevention.6

Summary points

Prevention of fractures includes reducing the number of falls, reducing the trauma associated with falls, and maximising bone strength at all ages

Pharmacological treatment is most clinically effective and cost effective when targeted at those who are at highest risk

Previous fracture and low bone density are strong risk factors for future fracture, and those at highest risk can be identified by combining these with other risk factors

Reasons for previous falls and unsteadiness in aged patients should be investigated

Treatment of concomitant conditions should be optimised

Bone fragility, falls, and people at high risk

Fractures occur in elderly people because of skeletal fragility. Appendicular fractures are usually precipitated by a fall. Falls account for 90% of hip fractures, and the risk of falling increases with age.7 Around a third of people aged 65 or over fall at least once a year, but only 1% of falls in women result in hip fracture.8,9 Whether fracture occurs depends on the impact from the fall and bone strength. Bone strength is related to mineral content, as assessed by bone densitometry, with the risk of fracture increasing proportionately with decrease in bone mineral density.10 Strategies to prevent fracture in an elderly population must therefore ensure maximum bone strength, reduce the occurrence of falls, and reduce the trauma associated with falls.

Compared with a younger woman, a 70 year old woman is five times more likely to sustain a hip fracture and three times more likely to incur any fracture during the rest of her life.11,12 However, there are some elderly people for whom the risk is much greater, and for them specific treatments to prevent fracture are more cost effective.13

Box 1: Risk factors (excluding falls) for bone loss, osteoporosis, and fracture in elderly people (adapted from various sources5,16,46,47)

Age over 75 years

Female

Previous fracture after low energy trauma

Radiographic evidence of osteopenia, vertebral deformity, or both

Loss of height, thoracic kyphosis (after radiographic confirmation of vertebral deformities)

Low body weight (body mass index < 19)

Treatment with corticosteroids

Family history of fractures owing to osteoporosis (maternal hip fracture)

Reduced lifetime exposure to oestrogen (primary or secondary amenorrhoea, early natural or surgical menopause (< 45 years))

Disorders associated with osteoporosis (previous low bodyweight; rheumatoid arthritis; malabsorption syndromes, including chronic liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease; primary hyperparathyroidism; long term immobilisation)

-

Behavioural risk factors

Low calcium intake (< 700 mg/d)

Physical inactivity

Vitamin D deficiency (low exposure to sunlight)

Smoking (current)

Excessive alcohol consumption

Factors can identify people most at risk of fracture, principally because of low bone mass (osteoporosis) or falls (boxes 1 and 2). Other factors include bone turnover and bone quality, assessed by bone markers and quantitative ultrasound, respectively.14,15 Frailty and comorbidity are also risk factors for poor outcome. Such factors could help determine whether bone densitometry is needed and choice of treatment.

Bone density has the strongest relation to fracture, but many fractures occur in women without osteoporosis. The possibility of fracture increases when low bone density is combined with other factors, but the exact interaction of these factors is unclear.16 Efforts are being made to describe the absolute risk for patients over the comprehensible time period of five to 10 years.13 This should help to indicate whether intervention is needed and to improve compliance.

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological agents increase bone mass either by decreasing bone resorption, with a secondary gain in bone mass, or by a direct anabolic effect. Preferably they also increase bone strength and quality. Randomised controlled trials of several of these drugs show a decrease in fractures within one to three years.

Drugs that specifically act on bone by decreasing resorption are bisphosphonates, calcitonin, selective oestrogen receptor modulators, and oestrogen. Combined calcium and vitamin D also has an antiresorptive action, and parathyroid hormone has become available as the first anabolic agent for bone (see table A on bmj.com).

Combined calcium and vitamin D

Combined calcium and vitamin D is the standard treatment for osteoporosis as well as a preventive measure, particularly in frail elderly people. In elderly institutionalised patients, further hip and nonvertebral fractures were decreased after three years' treatment with 1200 mg calcium and 20 μg (800 IU) vitamin D, with significant benefit at 18 months.17 A community based study found that vitamin D given once every four months decreased the overall risk of fracture by 39%, and in another study 800 IU of vitamin D given to elderly people (mean age 85) over a 12 week period increased muscle strength and decreased the number of falls by almost a half.18,19

Box 2: Risk factors for falls in elderly people

Intrinsic factors

-

General deterioration associated with ageing

Poor postural control

Defective proprioception

Reduced walking speed

Weakness of legs

Slow reaction time

Various comorbidities

-

Problems with balance, gait, or mobility

Joint disease

Cerebrovascular disease

Peripheral neuropathy

Parkinson's disease

Alcohol

Various drugs

-

Visual impairment

Impaired visual acuity

Cataracts

Glaucoma

Retinal degeneration

-

Impaired cognition or depression

Alzheimer's disease

Cerebrovascular disease

-

“Blackouts”

Hypoglycaemia

Postural hypotension

Cardiac arrhythmia

Transient ischaemic attack, acute onset cerebrovascular attack

Epilepsy

Drop attacks ?vertebrobasilar insufficiency

Carotid sinus syncope

Neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) syncope

Extrinsic factors

-

Personal hazards

Inappropriate footwear or clothing

-

Multiple drug therapy

Sedatives

Hypotensive drugs

Environmental factors

-

Hazards indoors or at home

Bad lighting

Steep stairs, lack of grab rails

Slippery floors, loose rugs

Pets, grandchildren's toys

Cords for telephone and electrical appliances

-

Hazards outdoors

Uneven pavements, streets, paths

Lack of safety equipment

Snowy and icy conditions

Traffic and public transportation

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are potent antiresorptive agents that block osteoclast action with little effect on other organ systems (see table B on bmj.com). In large randomised controlled trials, the bisphosphonate alendronate reduced both vertebral and non-vertebral fractures.20,21 It is most beneficial in those at highest risk–women with at least one prevalent vertebral fracture or osteoporosis. Symptomatic vertebral fractures were decreased by 28-36% over four years' treatment, whereas the risk of hip fracture was reduced by just over a half.20 Risedronate similarly reduces the incidence of vertebral fractures.22,23 A study of risedronate specifically designed to evaluate its effect on hip fracture showed that the incidence of hip fractures was decreased only in elderly women included because of a combination of low bone mass and risk factors.24 The effect was not significant in women included because of risk factors alone.24

The daily dosing regimens of bisphosphonates are complex, for reasons of absorption and gastric side effects. To maximise uptake, tablets must be taken after an overnight fast, with a full glass of water, and food avoided for half an hour. The need for such measures may be overcome with the new weekly dosing regimen for both agents.25,26

Etidronate was the first available bisphosphonate. It is used cyclically to treat osteoporosis, as overdosage may cause defects in mineralisation. No randomised controlled trials have been primarily powered to evaluate the effect of this drug on fracture.27,28 New compounds based on the primary bisphosphonate structure are being developed. The interval between doses has been increased between two and 12 months, which would be beneficial, particularly in elderly frail patients. At least two of these compounds, zolendronate and ibandronate, given intravenously or orally, are undergoing clinical trials.

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators selectively block conformational changes of the oestrogen receptor. In postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene, vertebral fractures were decreased by 30% over three years, whereas no effect was seen on non-vertebral fractures.29 A significant decrease in the number of new cases of breast cancer was also seen.30

Oestrogen

Preventing fractures in women with osteoporosis by giving oestrogen replacement therapy remains controversial. Large size studies of its effects on fracture have been lacking, and the indication for efficacy has relied on observational studies. The recent report from the Women's Health Initiative study on hormone replacement therapy is the first large scale randomised controlled trial in women aged 50-79. Hip and vertebral fractures were decreased by 34%, and the overall reduction in fracture risk was 24%.31 However long term side effects, particularly breast cancer, and absence of benefits for cardiovascular events limit the indications for use. The primary target group for oestrogen replacement therapy is therefore not elderly women with osteoporosis but women soon after menopause, to eliminate climacteric symptoms.

Calcitonin

Calcitonin is an endogenous inhibitor of bone resorption, which acts by suppressing osteoclasts. Salmon calcitonin is available as subcutaneous injections or a nasal spray. It is about 10 times more potent than normally produced human calcitonin. Although several studies have shown effects on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women, the effect on fracture has been less well studied. When salmon calcitonin 200 IU daily was, however, given to postmenopausal women, new vertebral fractures were decreased by 33% despite a small effect on lumbar bone mineral density.32 This has been interpreted as a quality effect of antiresorptive agents beyond the effect on bone mineral density.

Parathyroid hormone

Parathyroid hormone has a dual effect on bone. Continuous dosing or increased endogenous secretion leads to bone resorption, whereas intermittent dosing has a pronounced anabolic effect. Recombinant human parathyroid hormone given as subcutaneous injections is promising, decreasing vertebral and non-vertebral fractures by 65-69% and 53-54%, respectively, and markedly increasing bone mass in under two years.33

Impact and prevention of falls

Measures to prevent falls should be implemented in elderly people.34,35 This has potential benefit against appendicular fractures. It is difficult to identify those at most risk; a previous fall is a strong indicator, and important determinants are weakness of the legs, poor gait, and impaired balance and coordination.35 Recommendations have been made for assessing risk (box 3), although at present there is no fully evaluated tool for this. Effective prevention involves identifying and modifying where possible intrinsic, extrinsic, and environmental risk factors (see box 2).36 Social service staff and healthcare workers should be aware of these factors. Individually tailored programmes or Tai Chi can help improve balance and steadiness.36–39 A meta-analysis of four controlled trials of 1016 community dwelling women and men aged 65 to 97 years found that individually prescribed programmes of muscle strengthening and balance retraining exercises reduced the number of falls by 35%, benefiting most those over 80.39 However, there is little evidence as yet that fall prevention reduces the risk of fracture.

Box 3: Assessment of elderly people for risk of falls (adapted from guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons35 with permission of Blackwell)

Approach as part of routine care (not presenting after falls)

Elderly people should be asked at least once a year about falls

Elderly people who report a single fall should be observed as they stand up from a chair without using their arms, walk several paces, and return (get up and go test). Those showing no difficulty or unsteadiness need no further assessment

Approach to those presenting after one or more falls, or with abnormalities of gait or balance, or who report recurrent falls

Elderly people who present because of a fall, report recurrent falls in past year, or show abnormalities of gait or balance should undergo a fall evaluation. This should be performed by an experienced clinician, which may necessitate referral to a specialist

A fall evaluation includes a history of circumstances around the fall, drugs, acute or chronic medical problems, and mobility levels; an examination of vision, gait and balance, and function of the leg joints; an examination of basic neurological function, including mental status, muscle strength, peripheral nerves of the legs, proprioception, reflexes, and tests of cortical, extrapyramidal and cerebellar function; assessment of basic cardiovascular status including heart rate and rhythm, postural pulse and blood pressure and, if appropriate, heart rate and blood pressure responses to carotid sinus stimulation

Externally applied devices can protect against the impact of falls. External hip protectors decreased hip fractures in institutionalised patients, although their role in frequent fallers in the community is still being evaluated.40 The main limitation is compliance.

Lifestyle

A sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, smoking, and alcohol misuse are detrimental to bone health. Maintaining a strong skeleton at all ages relies on mechanical stimuli from weight bearing and physical activity. Programmes for physical exercise may increase bone mass by only a marginal amount,41 but loss of mobility results in a rapid decrease in bone mass and loss of physical fitness, particularly in elderly people.

Poor nutrition is common in elderly people, especially frail elderly people, and several studies show low body weight and body mass index associated with hip fracture.42 Protein supplementation has also improved outcome after hip fracture.43 Adequate intake of all nutrients, including calcium and vitamin D, is important. Smoking carries a moderate and dose dependent risk for osteoporosis and fracture, which diminishes over time with cessation.44

Selective case finding

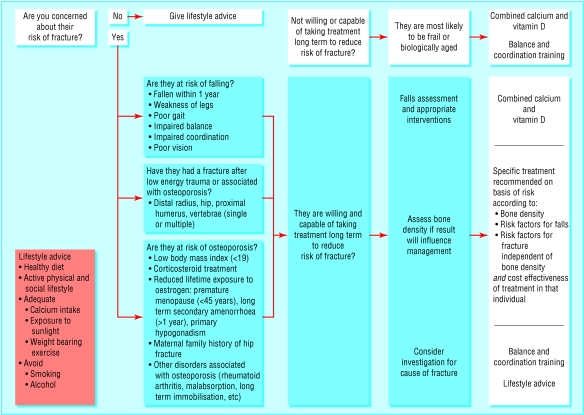

A selective case finding approach is recommended to recognise and treat those elderly people most at risk, ideally before the first fracture.1,45 High risk individuals may be identified from risk factors for bone fragility or susceptibility to trauma. The key questions relate to previous fragility fracture, previous falls or unsteadiness, and risk factors for osteoporosis or low bone mass (fig 1). Positive responses should lead to a full assessment to confirm risk, provided the patient agrees to and is able to follow instructions for pharmacological treatment. Those at risk of osteoporosis should be assessed by bone mineral density measurement with dual energy X ray absorptiometry at the hip and spine if it will influence management (fig 2). Measurement of the calcaneus by ultrasonography may be used as an intermediate assessment method if dual energy X ray absorptiometry is not feasible. Patients with low values can then be referred for full assessment.

Fig 1.

When and how to assess risk of future fracture in elderly people

Fig 2.

Measurement of bone mineral density at the hip and lumbar spine by dual energy absorptiometry

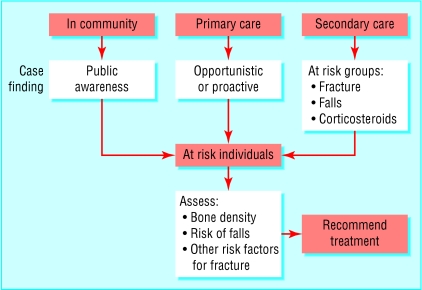

A risk assessment may be performed opportunistically or proactively (fig 3). Increasing the awareness of health professionals to recognise those at risk is central to the implementation of selective case finding. In particular all patients after age 50 who sustain fractures that could relate to osteoporosis should be identified at the time of fracture treatment. Integrated care pathways should be jointly developed to ensure appropriate investigation, including assessment of possible causes of fracture and bone density measurements, followed by treatment. Elderly people themselves should be aware of their potential risk and be encouraged to ask appropriate questions.

Fig 3.

Prevention of fracture

Selection of treatment and monitoring response

Management of people at risk of fracture should be tailored to their risks and needs. Treatment should always couple any antiresorptive agent along with non-pharmacological interventions (box 4).

The prevention of fracture can be measured only at the population level. Measurement of bone density or biochemical bone markers can be used in the individual as an indicator of treatment effect, but in clinical practice lack of long term compliance is the principal reason for poor response. Good patient education with re-enforcement is necessary to improve this. If bone density is measured again, it is not meaningful until after two years because of the precision error of available bone densitometers and the low rate of change in bone mass. If the patient tolerates treatment well, the second measurement can be delayed for three or four years providing there is a predetermined plan for continued treatment. Falls in the last year can be asked about to review effect of prevention. For those who have sustained a fracture, the impact on their quality of life can be monitored by a few simple questions, which could be used on a regular basis to provide a simple and rapid evaluation (box 5). It is also important to know if a local fracture prevention strategy is making a difference, and effectiveness can be measured by various indicators such as the success of case finding, numbers of fractures, and fracture outcome.3

With our current state of knowledge it will be possible to reduce the burden of osteoporosis in elderly people. Unfortunately, predicting and preventing all fractures is still beyond our abilities, but there has been progress in our understanding of what was until recently a silent epidemic.

Box 4: Recommendations for prevention of fracture in elderly people based on risk assessment (adapted from Royal College of Physicians guidelines1)

Indications

-

Bone mineral density T score* ≥1 (normal)

Advise on lifestyle

-

Bone mineral density T score -1 to -2.5 (osteopenia)

Advise on lifestyle

Consider combined calcium 1 g and vitamin D 800 IU, depending on intake

-

Bone mineral density T score ≤2.5 (osteoporosis)

Investigate for causes of osteoporosis

Advise on lifestyle and ensure adequate intake of combined calcium and vitamin D

Consider pharmacological treatment

Interpret result in context of age in frail elderly people (Z score)

-

Frail, biologically aged, or institutionalised

Consider intake of combined calcium 1 g and vitamin D 800 IU

Perform falls assessment

Consider hip protectors

Low bone mineral density and additional risk factors

Bone mineral density T score -1 to -2.5 plus fracture after low energy trauma or high risk of falls or other risk factors for fracture (checklist)

-

Investigate for causes of fracture

Perform falls assessment

Advise on lifestyle and ensure adequate intake of combined calcium and vitamin D

Consider pharmacological treatment

-

Bone mineral density T score ≤2.5 plus fracture after low energy trauma

Investigate for causes of fracture

Investigate for causes of osteoporosis

Perform falls assessment

Advise on lifestyle and ensure adequate intake of combined calcium and vitamin D

Consider pharmacological treatment

-

Multiple vertebral fracturesInvestigate for causes of fractureInvestigate for causes of osteoporosisPerform falls assessmentAdvise on lifestyle and ensure adequate intake of combined calcium and vitamin DConsider pharmacological treatmentIn elderly people with multiple vertebral fractures and no access to bone densitometry, treatment may be initiated without measurement of bone density

-

*T score compares bone mineral density to peak bone mass.

Box 5: Simple questionnaire used to monitor quality of life after fracture (adapted from Doherty et al48)

Have your daily activities been limited by pain during the past week?

Are you able to wash and dress yourself?

Have you walked outside during the past week?

Are you content with your current state of health?

Additional educational resources

Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group–the group reviews science from an evidence based perspective, using rigorous criteria for evaluation of efficacy or risk (www.cochranelibrary.com)

International Osteoporosis Foundation–this international organisation assembles professionals, patient support groups, and industry with an interest in osteoporosis (www.osteofound.org)

International Bone and Mineral Society BoneKEy-Osteovision–this website is a central repository of knowledge in the field of bone, cartilage, and mineral metabolism

American Society for Bone and Mineral Research–this organisation focuses on research in musculoskeletal, including both basic and clinical science (www.asbmr.org)

Sambrook P, Woolf AD. Osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2001:335- 515–an update on diagnosis and management of osteoporosis

Information for patients

International Osteoporosis Foundation–patient support groups and national societies for osteoporosis can be found through this website for most countries (www.osteofound.org)

National Osteoporosis Society–UK national charity dedicated to eradicating osteoporosis and promoting bone health in both men and women. Website provides useful information for the public, patients, and health professionals (www.nos.org.uk)

National Osteoporosis Foundation, USA–the leading US voluntary health organisation for osteoporosis, which provides information for patients and health professionals (www.nof.org)

NHS Direct–provides a wide range of information on osteoporosis, its prevention and treatment (www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/en.asp?TopicID=340)

Ongoing research

Defining absolute risk over 5-10 years for different age groups in both women and men

Evaluation of the effect of hip protectors in non-institutionalised people, including compliance

Development of simple fall prevention strategies in the community and evaluation of their effect on fracture

Long term studies evaluating the effect on falls of long term balance and coordination training in elderly and elderly frail people

Evaluation of annual vitamin D supplementation

Long term effectiveness of bisphosphonate therapy

Development of pharmacological agents with more favourable dosing regimens, particularly for frail elderly people

Understanding effects of pharmacological agents on bone quality to understand better how drugs prevent fracture

Population based studies in men to define sex specific risk factors and intervention levels for bone mineral density

Supplementary Material

Tables and

references of trials showing effects of pharmacological treatment appear on

bmj.com

Tables and

references of trials showing effects of pharmacological treatment appear on

bmj.com

Competing interests: ADW has received reimbursement from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Procter and Gamble, Lilly, and Wyeth for attending symposiums and speaking at educational meetings. He has also received reimbursement from Merck Sharp and Dohme for consultancy and research. KA has received reimbursement from AstraZeneca, Aventis, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Nycomed for attending symposiums and for speaking at educational meetings. She has also received reimbursement from Aventis and Roche for occasional consultancy on national and international advisory boards.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians. Osteoporosis: clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment. London: RCP, 1999. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians. Osteoporosis: clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment. Update on pharmacological interventions and an algorithm for management. London: RCP, 2000.

- 3.National Osteoporosis Society. Primary care strategy for osteoporosis and falls. Bath: National Osteoporosis Society, 2002.

- 4.Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation www.agreecollaboration.org/ (accessed 1 June 2003).

- 5.Jordan KM, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2002;16: 795-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogmark C, Sernbo I, Johnell O, Nilsson JA. Incidence of hip fractures in Malmo, Sweden, 1992-1995. A trend-break. Acta Orthop Scand 1999;70: 19-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youm T, Koval KJ, Kummer FJ, Zuckerman JD. Do all hip fractures result from a fall? Am J Orthop 1999;28: 190-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake AJ, Morgan K, Bendall MJ, Dallosso H, Ebrahim SB, Arie TH, et al. Falls by elderly people at home: prevalence and associated factors. Age Ageing 1988;17: 365-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC. Falls. N Engl J Med 1994;331: 872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 1996;312: 1254-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonsson B, Kanis J, Dawson A, Oden A, Johnell O. Effect and offset of effect of treatments for hip fracture on health outcomes. Osteoporos Int 1999;10: 193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 2001;29: 517-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Dawson A. Ten-year risk of osteoporotic fracture and the effect of risk factors on screening strategies. Bone 2002;30: 251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clowes JA, Eastell R. The role of bone turnover markers and risk factors in the assessment of osteoporosis and fracture risk. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;14: 213-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gluer CC, Hans D. How to use ultrasound for risk assessment: a need for defining strategies. Osteoporos Int 1999;9: 193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 1995;332: 767-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. N Engl J Med 1992;327: 1637-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT. Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ 2003;326: 469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Dick W, Akos R, Knecht M, Salis C, et al. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18: 343-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 1996;348: 1535-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998;280: 2077-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA 1999;282: 1344-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reginster JY, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, Hooper M, Roux C, Brandi ML, et al. Randomised trial of the effects of risedronate on vertical fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2000;11: 83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med 2001;344: 333-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnitzer T, Bone HG, Crepaldi G, Adami S, McClung M, Kiel D, et al. Therapeutic equivalence of alendronate 70 mg once-weekly and alendronate 10 mg daily in the treatment of osteoporosis. Alendronate Once-Weekly Study Group. Aging (Milano) 2000;12: 1-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown JP, Kendler DL, McClung MR, Emkey RD, Adachi JD, Bolognese MA, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of risedronate once a week for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. Calcif Tissue Int 2002. ;71: 103-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storm T, Thamsborg G, Steiniche T, Genant HK, Sorensen OH. Effect of intermittent cyclical etidronate therapy on bone mass and fracture rate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 1990;322: 1265-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts NB, Harris ST, Genant HK, Wasnich RD, Miller PD, Jackson RD, et al. Intermittent cyclical etidronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 1990;323: 73-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nickelsen T, Genant HK, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. JAMA 1999;282: 637-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cauley JA, Norton L, Lippman ME, Eckert S, Krueger KA, Purdie DW, et al. Continued breast cancer risk reduction in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene: 4-year results from the MORE trial. Multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65: 125-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288: 321-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chesnut CH III, Silverman S, Andriano K, Genant H, Gimona A, Harris S, et al. A randomized trial of nasal spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis: the prevent recurrence of osteoporotic fractures study. PROOF Study Group. Am J Med 2000;109: 267-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis 1. N Engl J Med 2001;344: 1434-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Health. National service framework for older people. London: DoH, 2001.

- 35.Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49: 664-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2001; 3: CD000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1999;353: 93-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feder G, Cryer C, Donovan S, Carter Y. Guidelines for the prevention of falls in people over 65. The Guidelines' Development Group. BMJ 2000;321: 1007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Gardner MM, Devlin N. Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: a meta-analysis of individual-level data. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50: 905-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker MJ, Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ. Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(2): CD001255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wallace BA, Cumming RG. Systematic review of randomized trials of the effect of exercise on bone mass in pre- and postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 2000;67: 10-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akesson K, Vergnaud P, Gineyts E, Delmas PD, Obrant KJ. Impairment of bone turnover in elderly women with hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 1993;53: 162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzoli R, Ammann P, Chevalley T, Bonjour JP. Protein intake and bone disorders in the elderly. Joint Bone Spine 2001;68: 383-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerdhem P, Obrant KJ. Effects of cigarette-smoking on bone mass as assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and ultrasound. Osteoporos Int 2002;12: 932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Report on osteoporosis in the European Community: action for prevention. Luxembourg: European Communities, 1998.

- 46.Espallargues M, Sampietro-Colom L, Estrada MD, Sola M, del Rio L, Setoain J, et al. Identifying bone-mass-related risk factors for fracture to guide bone densitometry measurements: a systematic review of the literature. Osteoporos Int 2001;12: 811-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet 2002;359: 1929-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doherty M, Dacre J, Dieppe P, Snaith M. The `GALS' locomotor screen. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51: 1165-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.