Intensive care is initiated daily for approximately 2000 older adults (age ≥65 years) in US emergency departments (EDs).1 Unfortunately, most older adults do not fully comprehend the risk of developing a new disability as a result of their critical illness.2 During the last 6 months of life, 75% of older adults visit the ED, and 30% of these patients start intensive care.3,4 Intensive care use in this population increased from 18.5% in 1993 to 24.7% in 2002, resulting in an annual healthcare expenditure of $108 billion.5,6 Although the decision to initiate intensive care often occurs in the ED and emergency physicians recognize the responsibility to provide patient-centered care, the communication tasks are often relegated to not-fully-trained resident physicians.7,8 In addition, no standardized methods exist to guide physicians in leading critical shared decision-making regarding initiating intensive care in the ED.9–11 In this issue of Annals of Emergency Medicine, Sanders et al12 present a qualitative study describing the attitudes of Canadian emergency medicine residents about making recommendations for life-sustaining treatments during acute health decompensations. Their results are illuminating for our field.

Making a recommendation for treatment is a fundamental skill in clinical practice. Leveraging clinicians’ medical expertise, patients entrust physicians to explain the risks, benefits, and alternatives of treatment and make a recommendation. Physicians usually have no hesitation about the recommendations for routine conditions (eg, recommending wrist reduction in previously healthy patients with a broken wrist). For older adults with limited life expectancy, however, even seasoned emergency physicians struggle to make patient-centered recommendations because of prognostic uncertainty. In this study, the authors explored how emergency medicine residents think about making recommendations for life-sustaining treatments for seriously ill older adults. The authors asked them to review 2 cases consecutively (the first case with routine medical decision-making and the second with end-of-life decision-making) and explored their thoughts on making recommendations. However, the resulting study design was not devoid of weaknesses. Using the first case, the respondents recognized that clinicians routinely make recommendations for patients who are not at the end of life. Hence, contrasting case one (ie, the routine case) with case 2 (ie, the end-of-life case) likely introduced a priming informational bias.13

Strikingly, the end-of-life case did not contain a description of the patient’s values and goals. Rather, it highlighted the poor prognosis (eg, advanced age) and clinician-perceived futility (eg, worsening despite full resuscitation) and then asked the respondents to do something that no palliative care clinician would likely ever do, namely to make a recommendation about life-sustaining treatment without knowing patients’ values and goals. Not surprisingly, the respondents’ answers did not reveal how to incorporate patients’ values and goals into a recommendation, signaling a lack of familiarity with what constitutes patient values in the first place (eg, trade-offs, worries, etc).14

Unlike prior literature, this study observed that emergency medicine residents “felt a sense of duty” to make recommendations.15 The authors report that many residents experienced moral distress during these conversations because of a perceived duty to provide intensive care despite the potential futility of intensive treatment. The residents’ moral distress is understandable, given that they are trying to make recommendations for end-of-life decisions based solely on anticipated poor prognosis and physician-perceived futility of care. This finding is a clear illustration of residents’ paucity of clinical experience and lack of formal training on how to incorporate patients’ values and goals into end-of-life decision-making. A strength of the study is that it has exposed the nature of a crucial gap in emergency medicine training.

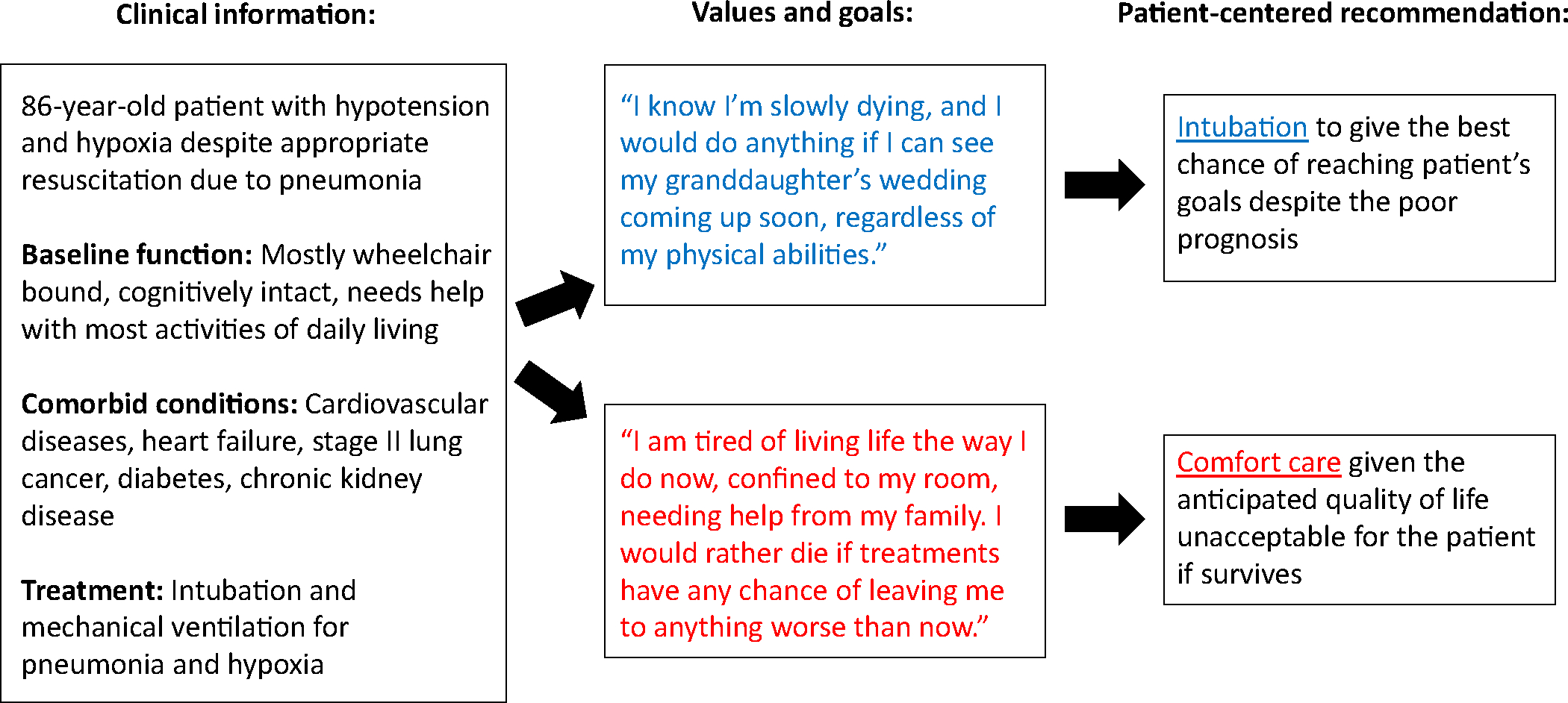

Patient-centered recommendations require the following 3 key steps: 1) evaluate the functional prognosis based on the patient’s baseline quality of life and treatment options; 2) establish the patient’s priorities based on the prognosis; and 3) formulate the recommendation most suitable to patient’s priorities, likely functional prognosis, and available treatment options. Even if 2 patients have the same baseline function, quality of life, prognosis, and treatment effectiveness, the patient’s values and goals alter what the patient-centered recommendations would be (Figure). Although these methods are well established, the current evidence suggests low adoption of these practices by experienced emergency physicians.14–17 In a recent cross-sectional study of self-reported practice patterns among emergency physicians (N=161), only one-third reported making recommendations about life-sustaining treatment for patients who were seriously ill in their clinical practice. Most emergency physicians focus their conversations on the risks of procedures (eg, intubation) rather than on asking about patients’ values.17 Emergency medicine residents’ approach to such conversations has not been well studied, and the findings stand in contrast to what we know about practice patterns of more experienced emergency physicians, most of whom do not report making such recommendations.17 In other words, a critical gap in clinical practice exists between emergency medicine residents’ desire to provide patient-centered recommendations and what current attending emergency physicians report doing.

Figure.

Simplified examples of patient-centered recommendations incorporating patient’s values and goals.

This study demonstrates that when prompted, emergency medicine residents recognize the opportunities for skill improvement and want to make patient-centered recommendations. It builds on previous work examining the state of goals of care conversations in the ED.18 Goals of care conversations are procedural skills that can be taught, learned, and deliberately practiced, which have the potential to result in improved patient-centered outcomes and reduced nonbeneficial treatments.19–22 Yet, recent studies suggest a clear gap in clinical practice: emergency physicians, especially resident physicians, want to provide patient-centered recommendations about life-sustaining treatment, but most of them are not familiar with how to incorporate patients’ values and goals into such recommendations. Furthermore, the study findings raise questions about our field’s current understanding of how to formulate patient-centered recommendations for life-sustaining treatment in patients near the end of life.

So why is this happening in our field? Several potential reasons exist. First, for experienced emergency physicians, focusing on patients’ values and goals to make patient-centered recommendations regarding life-sustaining treatments is easier said than done. Time-pressured environment, prognostic uncertainty, and years of moral distress from humbling end-of-life cases may prevent many experienced emergency physicians from making patient-centered recommendations. As a result, they often make recommendations based on the prognosis for survival rather than the anticipated quality of life after intensive care. However, this approach fails to account for what is important to most older adults. More than 70% of older adults report that at the end of life, they prefer to focus on the quality of life rather than life extension and would even give up one year of life to avoid dying in the ICU.23,24 Second, emergency physicians are often unfamiliar with long-term functional prognosis after intensive care for patients who are seriously ill. For example, among older adults who are intubated in the ED, one-third will die in the hospital, one-third will return home, and one-third will be placed in rehabilitation and nursing facilities—their one-year mortality may be as high as 70%.25,26 Moreover, emergency physicians may not be familiar with physical and cognitive declines for older adults after ED visits alone or with intensive care use.27,28 Without such familiarity, emergency physicians cannot make a calculated estimation of long-term outcomes for patients who are seriously ill faced with resuscitation decisions. Third, emergency physicians are often not trained to make patient-centered recommendations based on the patient’s values and goals, baseline function, quality of life, and prognosis. Perhaps younger generations of emergency physicians have benefited from improved education in serious illness care and now recognizing this shortcoming in our field. To address this issue, robust studies investigating these topics are currently underway in our field.29–31

During acute health decompensations for patients who are seriously ill, emergency physicians often bear the responsibility of steering treatment trajectories. Patients and families entrust us to make recommendations aligned with their values and preferences and are likely to achieve the best outcomes individualized for them. Although emergency physicians, including residents, aspire to provide patient-centered clinical recommendations, as a specialty, we simply have not garnered the serious illness communication skills to do it, which generated the education gap reflected in this study’s findings. The COVID-19 pandemic forced us to think harder about how to execute these decisions quickly. Innovative approaches emerged to partner with palliative care teams in the ED: embedded, in-person (ie, palliative care clinicians stationed in the ED) or telemedicine (ie, out-of-institution palliative care clinicians providing consults) palliative care clinicians actively screening for patients who may benefit from their consultations.32–35 These innovations resulted in markedly different goals of care, and some institutions have permanently adopted these approaches (eg, Massachusetts General Hospital).33–35 Yet, as a specialty, we need to ensure that we are well positioned to carry out patient-centered goals of care conversations that address values and goals through robust training and environmental support. Even for trained palliative care specialists, these high-acuity conversations in the ED remain challenging—we must tailor our serious illness communication training to be most feasible to our uniquely challenging settings (eg, EMTalk, an evidence-based serious illness communication training tailored for emergency physicians).36 Near the end of life, serious illness communication skills cannot guarantee patient-centered care concordant with patients’ wishes every time. It can, however, make this process as humane as it can be for both emergency physicians and patients and families.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Susan D. Block, MD and Naomi George, MD, MPH for their input and expertise in formulating this editorial.

Funding and support:

By Annals’ policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

Footnotes

All authors attest to meeting the four ICMJE.org authorship criteria: (1) Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND (2) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND (3) Final approval of the version to be published; AND (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supervising editor: Peter C. Wyer, MD. Specific detailed information about possible conflict of interest for individual editors is available at https://www.annemergmed.com/editors.

Contributor Information

Kei Ouchi, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Serious Illness Care Program, Ariadne Labs, Boston, MA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Naomi George, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico Health Science Center, Albuquerque, NM.

Jason Bowman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Serious Illness Care Program, Ariadne Labs, Boston, MA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Susan D. Block, Serious Illness Care Program, Ariadne Labs, Boston, MA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; Division of Palliative Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cairns C, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2020 emergency department summary tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2020-nhamcs-ed-web-tables-508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riegel B, Huang L, Mikkelsen ME, et al. Early post-intensive care syndrome among older adult sepsis survivors receiving home care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1277–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu W, Ash AS, Levinsky NG, et al. Intensive care unit use and mortality in the elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma G, Freeman J, Zhang D, et al. Trends in end-of-life ICU use among older adults with advanced lung cancer. Chest. 2008;133:72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine beds, use, occupancy, and costs in the United States: a methodological review. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2452–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, et al. Comparison of medical admissions to intensive care units in the United States and United Kingdom. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1666–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choosing wisely recommendations: American College of Emergency Physicians; 2018. Accessed June 22, 2023. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-college-of-emergency-physicians/

- 9.Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA, et al. Am I doing the right thing? Provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dy SM, Herr K, Bernacki RE, et al. Methodological research priorities in palliative care and hospice quality measurement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the population with serious illness: the “denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:S7–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders S, Cheung WJ, Bakewell F, et al. How emergency medicine residents have conversations about life-sustaining treatments in critical illness: a qualitative study using inductive thematic analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;82:583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeCoster J, Claypool HM. A meta-analysis of priming effects on impression formation supporting a general model of informational biases. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8:2–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernacki RE, Block SD. American College of Physicians High Value Care Task F. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen J, Blinderman C, Cole CA, et al. “I’d recommend…” how to incorporate your recommendation into shared decision making for patients with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1224–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouchi K, Lawton AJ, Bowman J, et al. Managing code status conversations for seriously ill older adults in respiratory failure. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76:751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prachanukool T, Aaronson EL, Lakin JR, et al. Communication training and code status conversation patterns reported by emergency clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouchi K, George N, Schuur JD, et al. Goals-of-care conversations for older adults with serious illness in the emergency department: challenges and opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:276–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa S Communication–the most challenging procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1268–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, et al. A randomized trial of a family-support intervention in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin EB, Buehler A, Halpern SD. Seriously ill patients’ willingness to trade survival time to avoid high treatment intensity at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:907–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouchi K, Jambaulikar GD, Hohmann S, et al. Prognosis after emergency department intubation to inform shared decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1377–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouchi K, Lo Bello J, Moseley E, et al. Long-term prognosis of older adults who survive emergency mechanical ventilation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:1019–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagurney JM, Fleischman W, Han L, et al. Emergency department visits without hospitalization are associated with functional decline in older persons. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, et al. Functional trajectories among older persons before and after critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:523–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benesch TD, Moore JE, Breyre AM, et al. Primary palliative care education in emergency medicine residency: a mixed-methods analysis of a yearlong, multimodal intervention. AEM Educ Train. 2022;6:e10823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grudzen CR, Shim DJ, Schmucker AM, et al. Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access (EMPallA): protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of specialty outpatient versus nurse-led telephonic palliative care of older adults with advanced illness. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grudzen CR, Brody AA, Chung FR, et al. Primary palliative care for emergency medicine (PRIM-ER): protocol for a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, stepped wedge design to test the effectiveness of primary palliative care education, training and technical support for emergency medicine. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aaronson EL, Daubman BR, Petrillo L, et al. Emerging palliative care innovations in the ED: a qualitative analysis of programmatic elements during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowman JK, Aaronson EL, Petrillo LA, et al. Goals of care conversations documented by an embedded emergency department-palliative care team during COVID. J Palliat Med. 2023;26:662–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J, Abrukin L, Flores S, et al. Early intervention of palliative care in the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1252–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores S, Abrukin L, Jiang L, et al. Novel use of telepalliative care in a New York City emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Emerg Med. 2020;59:714–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grudzen CR, Emlet LL, Kuntz J, et al. EM talk: communication skills training for emergency medicine patients with serious illness. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]