Abstract

Background

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is a rare autosomal recessive salt-losing tubulopathy. Mutations in the SLC12A3 gene encoding the renal thiazide-sensitive Na/Cl cotransporter in the distal renal tubule, cause GS. Identifying biallelic inactivating mutations in the SLC12A3 gene is the most common finding in GS, while the detection of renal calculi is relatively rare.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 33-year-old man admitted with recurrent limb weakness for six years. Laboratory tests showed hypokalemic alkalosis, hypocalciuria and renal potassium wasting; serum magnesium and aldosterone were normal, and ultrasound and computed tomography scans showed right-sided renal calculus. A hydrochlorothiazide test was performed, which showed a blunted response to hydrochlorothiazide. Next-generation sequencing identified triple mutations in SLC12A3, including novel splicing heterozygous mutations (c.2285+2T>C). He was administered with oral potassium chloride and spironolactone and maintained mild symptomatic hypokalemia during his follow-up.

Conclusions

The patient was diagnosed with Gitelman syndrome by genetic testing, accompanied by kidney stones. Although kidney stones are rare in Gitelman syndrome, they are not excluded as a criterion. The composition of kidney stones may be of significance for diagnosis and treatment. HIPPOKRATIA 2023, 27 (2):64-68.

Keywords: Gitelman syndrome, SLC12A3, triple mutations, renal calculus

Introduction

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is a salt-losing tubulopathy first described in 1966. GS is characterized by hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria and was recently regarded as the most commonly inherited renal tubular disorder with an estimated prevalence of up to 10/40,000 and steadily increasing in Asia. It is caused by biallelic inactivating mutations in the SLC12A3 gene, resulting in loss of function of the encoded Na/Cl cotransporter expressed in the apical membrane of cells lining the distal convoluted tubule1. Identifying biallelic inactivating mutations in the SLC12A3 gene is the most common and classic manifestation in GS, which is considered the criteria for establishing the diagnosis. Hypocalciuria is one of the classic GS features, due to which a normal renal ultrasound is proposed in the criteria for a GS diagnosis. Herein, we report a case of genetically confirmed GS with triple mutation and complicated with renal calculi.

Case Presentation

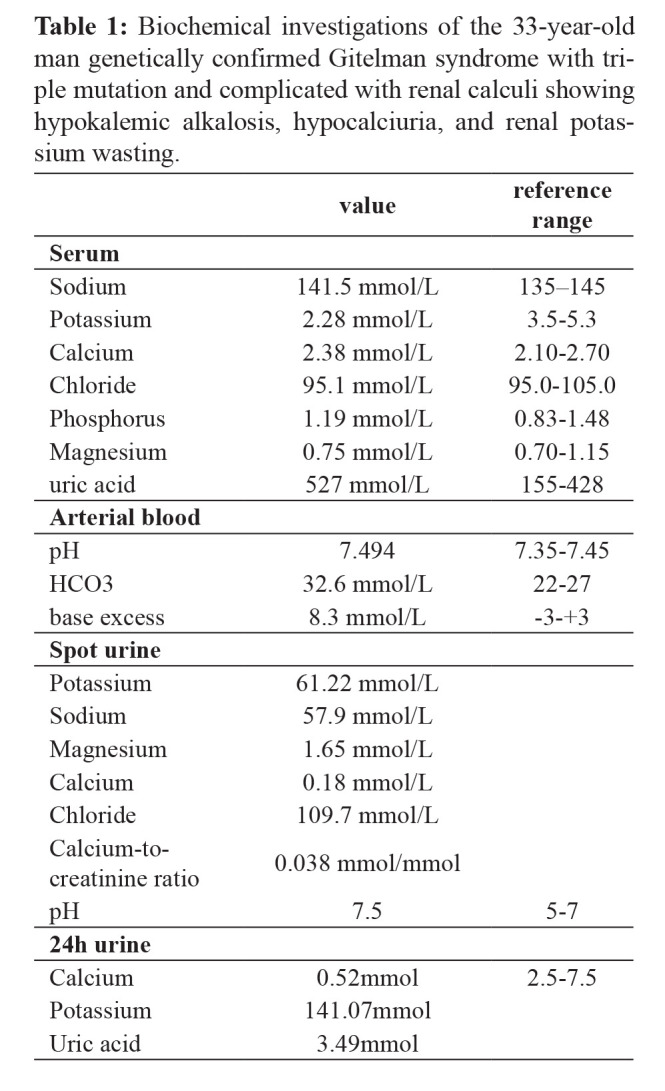

A 33-year-old male presented to the local hospital with a six-year history of progressive weakness in all four extremities and was diagnosed with hypokalemia. His condition improved following potassium chloride treatment, but the symptoms recurred irregularly. Ten days before this admission, he complained of severe backache; an ultrasonography examination showed a renal calculus in his right kidney. He had no history of diarrhea, polyuria, or arthritis, and he denied any laxative or diuretic use. His parents were non-consanguineous. There was no history of hypokalemia in the family. Physical examinations on admission were normal. Biochemical investigations revealed hypokalemia and normal serum magnesium levels. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed metabolic alkalosis. Additional biochemical testing showed hypocalciuria and renal potassium wasting (Table 1). The thyroid profile, plasma renin and aldosterone levels, and cortisol levels were all within normal range. The electrocardiogram was normal, while ultrasound imaging (Figure 1) and computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 2) showed right-sided renal calculus.

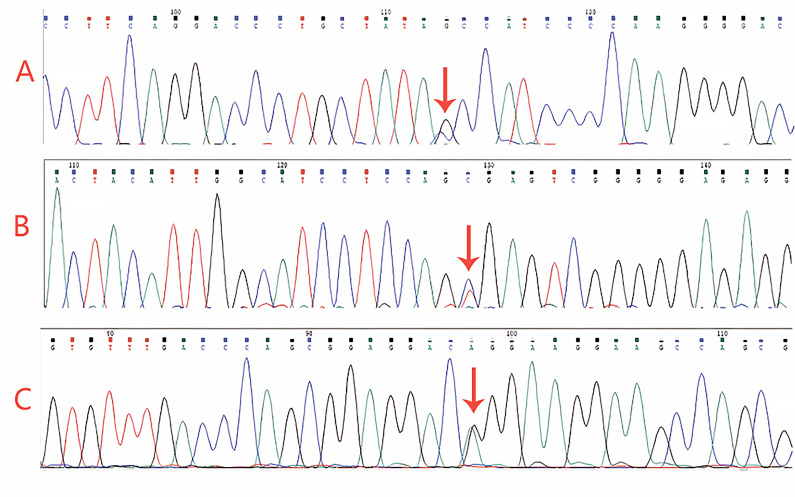

Table 1. Biochemical investigations of the 33-year-old man genetically confirmed Gitelman syndrome with triple mutation and complicated with renal calculi showing hypokalemic alkalosis, hypocalciuria, and renal potassium wasting.

Figure 1. Ultrasound imaging of the right kidney showing several strong echo spots.

Figure 2. Axial computed tomography image showing dense nodules in the right renal calyces (white arrows).

A hydrochlorothiazide test was performed according to the standard protocol2. The basic steps are as follows: the patient stops using spironolactone for seven days; within 15 minutes before the test, complete drinking 10 ml of water per kilogram of body weight and 150 ml of water every hour during the test; take orally 50 mg of hydrochlorothiazide in test’s first hour; perform urine tests every 30 minutes during the test, and take blood samples in the first and fourth hours of the test; calculate the excretion fraction of chloride ions before and after taking medicine. Chloride excretion was quantified, and the results indicated an increase of 0.65 % in the chloride excretion fraction (ΔFECl), which was below the reference range (<2.3 %). This finding indicated a blunted response to hydrochlorothiazide.

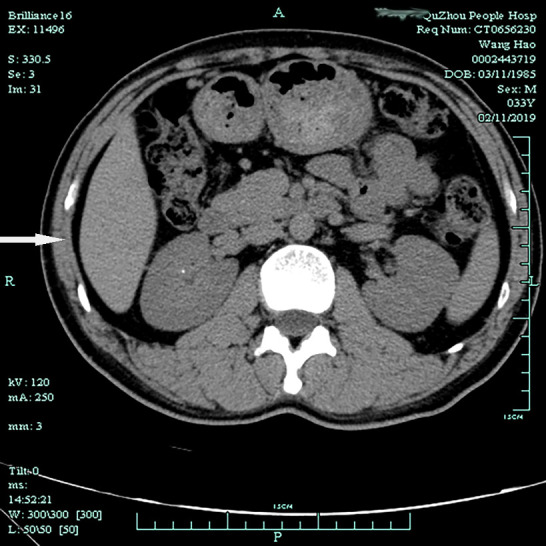

To confirm our clinical suspicion of GS, we performed genetic sequencing. Three heterozygous variants, including c.1108G>C (p.Ala370Pro), c.2285+2T>C (splicing), and c.2398G>A (p.Gly800Arg), were detected in the SLC12A3 (Figure 3). According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria, the variant c.1108G>C (p.Ala370Pro) was considered likely pathogenic; the variant c.2398G>A (p.Gly800Arg) was considered uncertain; and the novel variant c.2285+2T>C was pathogenic. The three mutations found in this test, in the SLC12A3 gene (p.Ala370Pro), (c.2285+2T>C), and (p.Gly800Arg) have frequencies less than 0.005 in the population. Among them, (p.Gly800Arg) and (p.Ala370Pro) mutations are located in the topological domain of the SLC12A3. After the boundary of this domain is disrupted, large-scale gene expression will be affected. Mutations (c.2285+2T>C) may affect the splicing of exon 18 and intron 18 of SLC12A318, thereby affecting its expression. Three mutations can form complex heterozygous mutations, ultimately leading to GS. Accordingly, the diagnosis of GS with renal calculi was established.

Figure 3. Gene sequencing results of the reported patient carrying: A) a heterozygous mutation (c.1108G>C, p.A370P) (arrow), B) a heterozygous mutation (c.2285+2T>C, splicing) (arrow), and C) a heterozygous mutation (c.2398G>A, p.G800R) (arrow) in the SLC12A3 gene.

Treatment

According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) recommendations, the target blood potassium for GS patients is 3.0 mmol/L. Potassium chloride sustained-release tablets (7.5 g/d) and spironolactone (20 mg twice daily) were administered orally. In addition, a potassium-rich diet was recommended. When oral potassium supplementation could not effectively maintain blood potassium levels, we increased the dose of spironolactone tablets (initially 20 mg once, then increased to 20 mg twice daily). After taking the medication, the patient’s blood potassium level remained above three mmol/L. However, after taking the medication for about three months, the patient began to develop breasts and refused to take further oral spironolactone tablets.

Outcome and follow-up

The weakness was significantly improved, but persistent hypokalemia (2.67-3.05 mmol/L) remained despite continuous oral potassium chloride tablet administration (7.5-10 g/d). Once the drug was discontinued, the patient developed severe hypokalemia (1.4 mmol/L).

Discussion

The diagnosis of GS is usually based on clinical symptoms and biochemical abnormalities. Genetic tests are also required, especially in cases presenting with atypical clinical manifestations. Identifying biallelic inactivating mutations in the SLC12A3 gene is an indispensable criterion for establishing the diagnosis of GS1. To date, more than 400 mutations of SLC12A3 have been identified3.

Three different mutations were detected in our patient, including a novel splicing mutation of c.2285+2T>C. Among this patient’s three gene mutation sites, p.Gly800Arg and p.Ala370Pro are missense mutations. In 2019, a previous study performed genetic analysis on SLC12A3 in patients with GS in China and revealed that more than 72 % of mutations in SLC12A3 were missense mutations4. The sp486asn and arg913gln have also been confirmed as frequent mutations, with a frequency of >3 %4. The missense mutation in the reported patient did not include the frequent mutation gene loci commonly reported in Chinese patients, and its frequency in the population is less than 0.005.

In addition to the two missense mutations, a new splice site mutation (c.2285+2T>C) was discovered in this patient, which has not been included in the human gene mutation database (HGMD) or Clinvar database. It is speculated that the newly discovered splice site mutation may affect the splicing of SLC12A3 exon 18 and intron 18, trigger nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), and affect gene expression. The current incidence of splice site mutation in Chinese GS patients is low, around 6 %4.

Although it is rare to observe patients with GS combining triple genetic mutations, cases were reported domestically and in other countries. Two genetic investigations in Chinese patients with GS were conducted in 2015 and 2016, indicating an incidence of 9.52 % (4/42) and 5.97 % (4/67) in triple-mutation, respectively5,6. Fifteen percent of GS patients were reported with three gene mutations in Taiwan7, and 7 % were reported abroad8. Three gene mutations combined with new splice site mutations are unique to the patient, reflecting the disease’s great genetic heterogeneity.

In terms of clinical manifestations, the degree of hypokalemia in the reported patient was particularly prominent. Under treatment with high-dose oral potassium chloride sustained-release tablets combined with spironolactone, the hypokalemia could only be partially restored and was destabilized immediately after drug withdrawal. The clinical manifestations of GS patients are different. Gene phenotype studies of GS patients in Mainland China9, Taiwan7, and Europe10 have confirmed that male patients have more severe hypokalemia and clinical symptoms than female patients. The discrepancy in sex hormones may explain this particular gender difference. It has been confirmed that the density of sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) in distal convoluted tubule (DCT) is affected by sex hormones11. Estrogens can regulate renal sodium and chlorine excretion by increasing the density of NCC. Meanwhile, more experiments have confirmed that in rat models, estradiol substitutes can repair the ultrastructure of distal convoluted tubules and the expression of NCC in the apical membrane of distal convoluted tubules12. Therefore, it can be speculated that estrogens can improve the clinical symptoms of female GS patients through their positive effect on NCC. In addition, some studies have documented the prevalence of splicing mutations in GS patients with severe clinical manifestations to be significantly high10. Transcript analysis demonstrated that splicing mutations of SLC12A3 lead to frameshifted mRNA subject to degradation by NMD. In conclusion, the patient’s gender and shear defective genes may be the determinants of severe hypokalemia.

Hypomagnesemia is one of the typical clinical manifestations of GS; however, the patient’s blood magnesium often remains normal. Thus, hypomagnesemia is a GS characteristic but not a necessary condition for its diagnosis. There have been many reports of GS combined with normal blood magnesium13, while in Japan, the percentage of GS patients with normal blood magnesium is reported as high as 45 %14. The regulation of blood magnesium is closely related to the epithelial magnesium channel transient receptor potential location channel subfamily m member 6 (TRPM6), which is expressed along the apical membrane of distal convoluted tubules and is responsible for regulating the intercellular transport of magnesium15. Hypomagnesemia in GS patients is regarded to be related to the down-regulation of TRPM6 detected by renal biopsy sections of GS patients using immunohistochemical methods13. It is presumed that hypomagnesemia in GS patients is related to the following mechanisms: A) TRPM6 shows a long-term progressive loss during NCC dysfunction, which can explain why most GS patients develop hypomagnesemia only in adolescence or adulthood. Jiang et al also confirmed that the course of GS patients with normal blood magnesium is relatively short13. B) Different domains of NCC protein have different functions. Japanese scholars found that patients with p.leu858his or p.arg642cys mutation have normal blood magnesium14. Therefore, the location of gene mutation is related to the regulation of TRPM6, and the changes in some amino acids may not lead to the downregulation of TRPM6.

According to the current consultation and guidance of KDIGO, one of the diagnostic conditions of GS patients is that renal ultrasound is normal, and should an ultrasound or other imaging examination indicate that nephrocalcinosis or nephrolithiasis, that is a feature against the diagnosis of GS1. GS patients often exhibit apparent hypocalcemia and polyuria in clinical practice, which explains why GS patients do not develop renal stones; however, this has been challenged by increasingly atypical cases reported recently. Two cases of gene-confirmed GS combined with renal calculi were reported in China16,17. The patient reported herein had also confirmed by color Doppler ultrasound and CT presence of renal calculi. The exclusion criteria recommended by KDIGO do not apply to these patients. However, through further analysis of patients’ urinary calcium, we still hold different views. The renal calculi of the first two patients were clearly calcium-containing stones, and both showed high urinary calcium for some reason. Nevertheless, this patient is the first case of low urinary calcium GS, complicated by renal stones. We assume that the patient’s kidney stones do not contain calcium salts; however, we lack adequate means to analyze further the stone’s components, such as detecting the concentration of oxalic acid or phosphate in the urine, which is a limitation of the current report. The assumption regarding the patient’s kidney stones composition is based on the Hounsfield units (HU) value displayed by the kidney CT image. The patient’s HU value was as low as 170, while an HU value generally higher than 800 indicates calcium-containing stones. We acknowledge that the KDIGO exclusion criteria are still appropriate as patients with GS may have renal stones, while the exclusion criteria emphasize whether they are calcium-containing stones. When renal calculi are detected in patients clinically suspected of GS, further clarifying the nature of stones is necessary. Non-calcium stones do not affect the diagnosis of GS. If GS patients are complicated with calcium-containing stones, more attention should be paid to detecting whether patients have increased urinary calcium due to other diseases.

Conclusion

In summary, we reported a GS case with novel heterozygous mutations c.2285+2T>C in the SLC12A3 gene and also variants c.1108G>C (p.Ala370Pro) and c.2398G>A (p.Gly800Arg). The patient had typical clinical symptoms and laboratory findings. Renal calculus was evident on ultrasound and CT imaging, which misguided the diagnosis. The finding of renal calculi makes this a unique case of GS and expands the horizon for further research. Should renal calculi be an exclusion criterion for GS? A better understanding of GS disease is still worth investigating.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We obtained ethical approval from the ethics committee of The Quzhou Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Quzhou People’s Hospital, and written informed consent from the patient before using his data for this publication.

References

- 1.Blanchard A, Bockenhauer D, Bolignano D, Calò LA, Cosyns E, Devuyst O, et al. Gitelman syndrome: consensus and guidance from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2017;91:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colussi G, Bettinelli A, Tedeschi S, De Ferrari ME, Syrén ML, Borsa N, et al. A thiazide test for the diagnosis of renal tubular hypokalemic disorders. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:454–460. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02950906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou H, Liang X, Qing Y, Meng B, Zhou J, Huang S, et al. Complicated Gitelman syndrome and autoimmune thyroid disease: a case report with a new homozygous mutation in the SLC12A3 gene and literature review. BMC Endocr Disord. 2018;18:82. doi: 10.1186/s12902-018-0298-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng Y, Li P, Fang S, Wu C, Zhang Y, Lin X, et al. Genetic Analysis of SLC12A3 Gene in Chinese Patients with Gitelman Syndrome. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:5942–5952. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Shi C, Cui Y, Li C, Tong A. Mutation profile and treatment of Gitelman syndrome in Chinese patients. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:293–299. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu T, Wang C, Lu J, Zhao X, Lang Y, Shao L. Genotype/Phenotype Analysis in 67 Chinese Patients with Gitelman’s Syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:159–168. doi: 10.1159/000448694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng MH, Yang SS, Hsu YJ, Fang YW, Wu CJ, Tsai JD, et al. Genotype, phenotype, and follow-up in Taiwanese patients with salt-losing tubulopathy associated with SLC12A3 mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1478–E1482. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamba G. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:423–493. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin SH, Shiang JC, Huang CC, Yang SS, Hsu YJ, Cheng CJ. Phenotype and genotype analysis in Chinese patients with Gitelman’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2500–2507. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riveira-Munoz E, Chang Q, Godefroid N, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Dahan K, et al. Transcriptional and functional analyses of SLC12A3 mutations: new clues for the pathogenesis of Gitelman syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1271–1283. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z, Vaughn DA, Fanestil DD. Influence of gender on renal thiazide diuretic receptor density and response. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5:1112–1119. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V541112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verlander JW, Tran TM, Zhang L, Kaplan MR, Hebert SC. Estradiol enhances thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter density in the apical plasma membrane of the distal convoluted tubule in ovariectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1661–1669. doi: 10.1172/JCI601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang L, Chen C, Yuan T, Qin Y, Hu M, Li X, et al. Clinical severity of Gitelman syndrome determined by serum magnesium. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:357–366. doi: 10.1159/000360773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimura J, Nozu K, Yamamura T, Minamikawa S, Nakanishi K, Horinouchi T, et al. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics in Patients With Gitelman Syndrome. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;4:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viering DHHM, de Baaij JHF, Walsh SB, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D. Genetic causes of hypomagnesemia, a clinical overview. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:1123–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3416-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong B, Chen Y, Liu X, Wang Y, Wang F, Zhao Y, et al. Identification of compound mutations of SLC12A3 gene in a Chinese pedigree with Gitelman syndrome exhibiting Bartter syndrome-liked phenotypes. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:328. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01996-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Q, Wang X, Min J, Wang L, Mou L. Kidney stones and moderate proteinuria as the rare manifestations of Gitelman syndrome. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22:12. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02211-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]