Abstract

Modeling complex eye diseases like age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and glaucoma poses significant challenges, since these conditions depend highly on age-related changes that occur over several decades, with many contributing factors remaining unknown. Although both diseases exhibit a relatively high heritability of >50%, a large proportion of individuals carrying AMD- or glaucoma-associated genetic risk variants will never develop these diseases. Furthermore, several environmental and lifestyle factors contribute to and modulate the pathogenesis and progression of AMD and glaucoma.

Several strategies replicate the impact of genetic risk variants, pathobiological pathways and environmental and lifestyle factors in AMD and glaucoma in mice and other species. In this review we will primarily discuss the most commonly available mouse models, which have and will likely continue to improve our understanding of the pathobiology of age-related eye diseases. Uncertainties persist whether small animal models can truly recapitulate disease progression and vision loss in patients, raising doubts regarding their usefulness when testing novel gene or drug therapies. We will elaborate on concerns that relate to shorter lifespan, body size and allometries, lack of macula and a true lamina cribrosa, as well as absence and sequence disparities of certain genes and differences in their chromosomal location in mice.

Since biological, rather than chronological, age likely predisposes an organism for both glaucoma and AMD, more rapidly aging organisms like small rodents may open up possibilities that will make research of these diseases more timely and financially feasible. On the other hand, due to the above-mentioned anatomical and physiological features, as well as pharmacokinetic and -dynamic differences small animal models are not ideal to study the natural progression of vision loss or the efficacy and safety of novel therapies. In this context, we will also discuss the advantages and pitfalls of alternative models that include larger species, such as non-human primates and rabbits, patient-derived retinal organoids, and human organ donor eyes.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, Glaucoma, Mouse model, Non-human primate model, Rabbit model, Age-related disease, Eye disease, Retina, Drusen, Geographic atrophy, Optic nerve degeneration

1. Introduction

Vision loss negatively impacts the quality of life of affected patients and their caregivers: Physically, through falls and injuries (Crews et al., 2016), economically since they may suffer the loss of employment, education and income and bear the burden of higher healthcare costs (Rein et al., 2022) and mentally, through increased psychological distress (Lundeen et al., 2022). Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and glaucoma represent the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide. Flaxman et al. estimated that globally in 2020, 8.8 million patients with AMD and 4.5 million individuals with glaucoma experienced moderate or severe vision impairment (Flaxman et al., 2017). The National Eye Institute projected in 2014 that the number of patients with advanced AMD in the United States will increase from 2.1 million to 3.7 million and those with glaucoma from 2.7 to 4.3 million by 2030 (Eye Disease Statistics, 2014). Since the prevalence of AMD and glaucoma increases with age, the resulting burden on our aging societies makes it ever more urgent to investigate the underlying causes and to find and improve treatments.

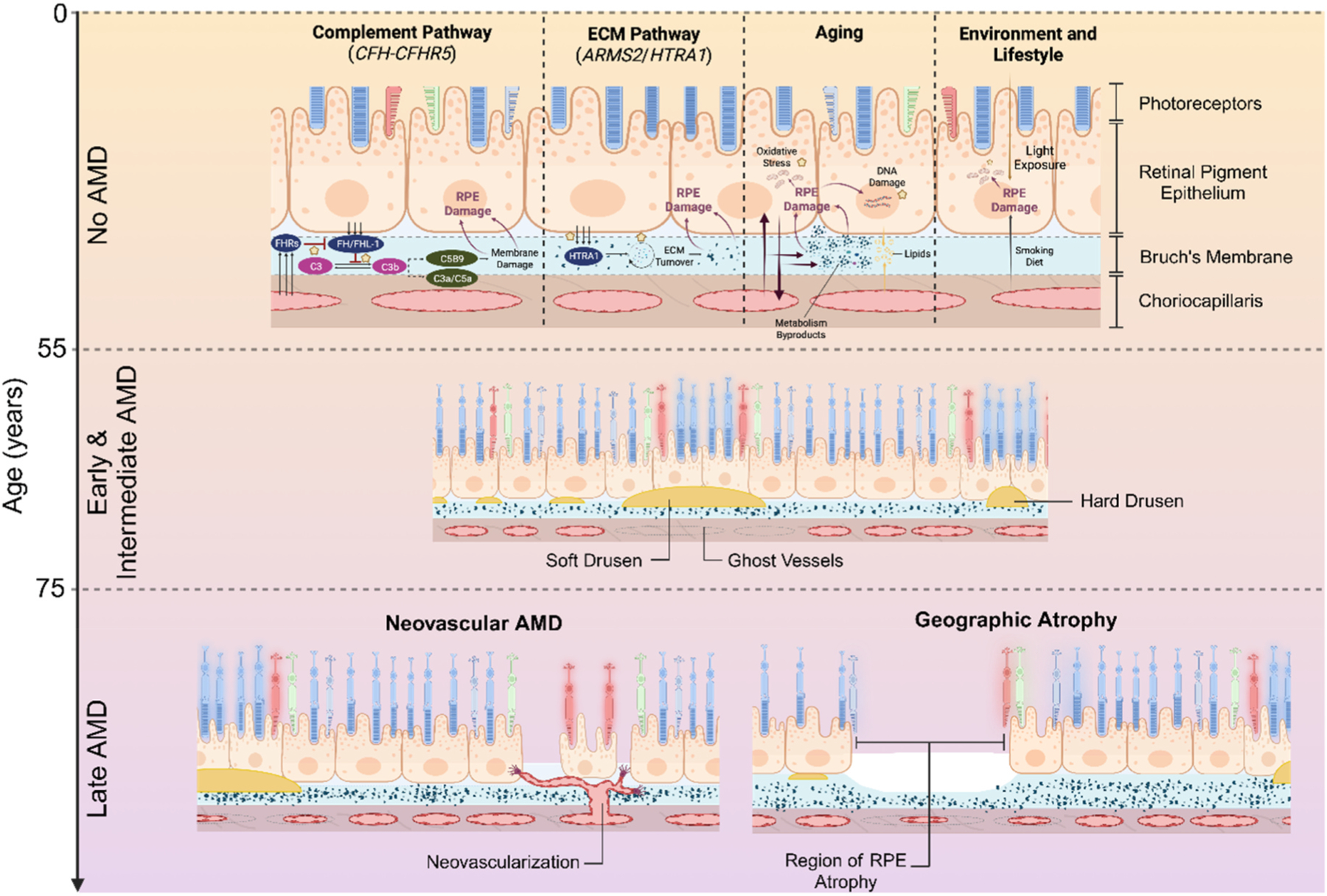

At first glance, the natural histories of AMD and glaucoma appear to differ greatly. AMD initiates and progresses at the outer blood-retina barrier, which mainly consists of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), Bruch’s membrane (BrM) and choriocapillaris. Dry AMD represents the more common manifestation of the disease, with mechanisms of onset that remain elusive. It commonly includes accumulation of deposits of extracellular material underneath the RPE that can aggregate into drusen (Fig. 1), thinning of the macula, atrophy of the RPE and fragility of the photoreceptor pigment interface with pigment epithelial detachments. Patients with pigmentary abnormalities, drusen and/or RPE detachment more likely advance to geographic atrophy (GA), which involves the formation and development of atrophic regions in the retina characterized by photoreceptor loss and/or to neovascular AMD with abnormal growth of structurally impaired choroidal and/or retinal blood vessels that can become leaky, leading to subretinal hemorrhages ((Fleckenstein et al., 2021), Fig. 2). Functionally, early or intermediate AMD affects the speed by which patients can adapt to darkness after bright light exposure, a phenomenon believed to be mainly due to compromised visual pigment chromophore delivery from the RPE ((Lee et al., 2020a; Owsley et al., 2016), Fig. 3A) specifically in the macula. In addition, a slower activation phase of light flash responses has been observed in both patients with dry and wet AMD (Fig. 3B). Although retinal remodeling, histological and metabolomic pathologies are also observed in regions adjacent to drusen outside of the central macula (Jones et al., 2016), the late forms of AMD substantially diminish patients’ quality of life due to loss of central vision, since AMD specifically affects the macula.

Fig. 1. Fundus and OCT images from early/intermediate AMD patient (A, B) and control subject (C, D).

Drusen can be seen as yellow spots in the fundus image (A) and as protrusions, as indicated by arrow heads, in the OCT image (B).

Fig. 2. Natural History of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Schematic showing pathways driving AMD-associated pathology, which develops primarily at the interface between retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), Bruch’s membrane (BrM) and choriocapillaris. These pathways are at play prior to the clinical onset of early and intermediate AMD and subsequent progression to late AMD.

Fig. 3. Altered dark adaptation (A) and dark-adapted ERG light responses in human AMD patients (B) and a mouse model of CFH variant (C).

(A) Recovery of visual sensitivity after bleach from control subjects (black) and from AMD patients (grey). (B) Leading edge of ERG light flash response from control (black) and dry (blue) and wet (red) AMD patients. (C) ERG light flash response amplitudes as a function of flash intensity in control (no high-fat diet, black; high-fat cholesterol-enriched diet, green) and in human CFH risk variant expressing mice (no high-fat diet, blue; high-fat cholesterol-enriched diet, pink). Adapted from (Murray et al., 2022), (A) (Dimopoulos et al., 2013), (B) (Landowski et al., 2019), (C).

Glaucoma refers to a group of diseases characterized by retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death and damage to the optic nerve (Fig. 4). In this review, we will focus on primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) as the most common type of the disease that affects the aging population and refer to it as glaucoma. In contrast to AMD that deprives patients of central vision, patients with glaucoma initially lose peripheral vision, which often goes unnoticed in the early disease stages and only later extends to the central retina. Moreover, unlike AMD in which the pathological progression involves the RPE or vascular components, the death of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) that form the optic nerve primarily characterizes glaucoma and often correlates with increased intraocular pressure (IOP) (Guo et al., 2005). However, despite their different pathophysiological presentation, both AMD and glaucoma mainly affect patients over 65 years and present as progressive conditions, in which advanced age, genetic risk variants, environmental factors and lifestyle combine to increase the odds of developing these debilitating diseases.

Fig. 4. Optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber changes in glaucoma patients diagnosed using fundus photography.

Glaucomatous eye (A) has larger cup (bright center) to rim ratio compared to control eye (B). Images in C–F are from the same subject who developed glaucoma within 4-year period. In C the nerve fibers look normal but start to disappear from regions indicated in arrows in D-F. At the time when image F was photographed, patient had developed visual field deficits. (A, B) from (Abramoff et al., 2007), and (C–F) from (Quigley et al., 1992).

For many decades, vascular defects secondary to neovascular AMD were managed with pan-retinal laser photocoagulation, which by its very nature destroys retinal tissue and thus makes loss of vision unavoidable (Macular Photocoagulation Study Group, 1982; The Moorfields Macular Study Group, 1982), although new approaches limit the degree of vision impairment linked to photocoagulation (Sher et al., 2013). Drugs that target vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) first became available in the early 2000s and have massively improved the prognosis and treatment of patients with neovascular AMD (Meyer and Holz, 2011). Nevertheless, a significant proportion of patients fail to respond to anti-VEGF drugs and many do not maintain initial vision gains (Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials Research, 2016). Treatment for GA is currently limited to pegcetacoplan and avacincaptad pegol, the first available treatments for GA, which were only recently approved by The Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These drugs only modestly reduce lesion growth, but unlike anti-VEGF therapies neither drug meaningfully improves vision within the first 18 months to two years (Patel et al., 2023; Apellis, 2022).

Glaucoma treatment centers on pharmacologically and/or surgically lowering IOP to slow the disease, although many patients continue to lose vision post-intervention (Weinreb et al., 2014). Disease progression despite treatment may result from IOP remaining higher than expected even with successful surgeries or 100% patient compliance with pharmacological intervention. Neuroprotective treatments to increase RGC survival in glaucoma remain unavailable despite many previous and ongoing studies (Hernandez et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2010; Khatib and Martin, 2020; Osborne et al., 2018; WoldeMussie et al., 2001). Clearly, significant challenges to developing effective sight-saving therapies for AMD and glaucoma patients remain and many small molecule and gene therapies for AMD and glaucoma are currently under investigation, which require testing in animal models with human disease relevance. This review will complement others on AMD (e.g., (de Jong et al., 2021; Fleckenstein et al., 2021; Merle et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2022; Rozing et al., 2020)) and glaucoma (e.g., (Ekici and Moghimi, 2023; Krizaj, 1995; Shalaby et al., 2022; Stein et al., 2021; Tezel, 2022; Wang et al., 2022)) by discussing the strengths and weaknesses of currently available animal models to elucidate the roles of genetics, aging and environment in disease pathogenesis and progression of AMD and glaucoma.

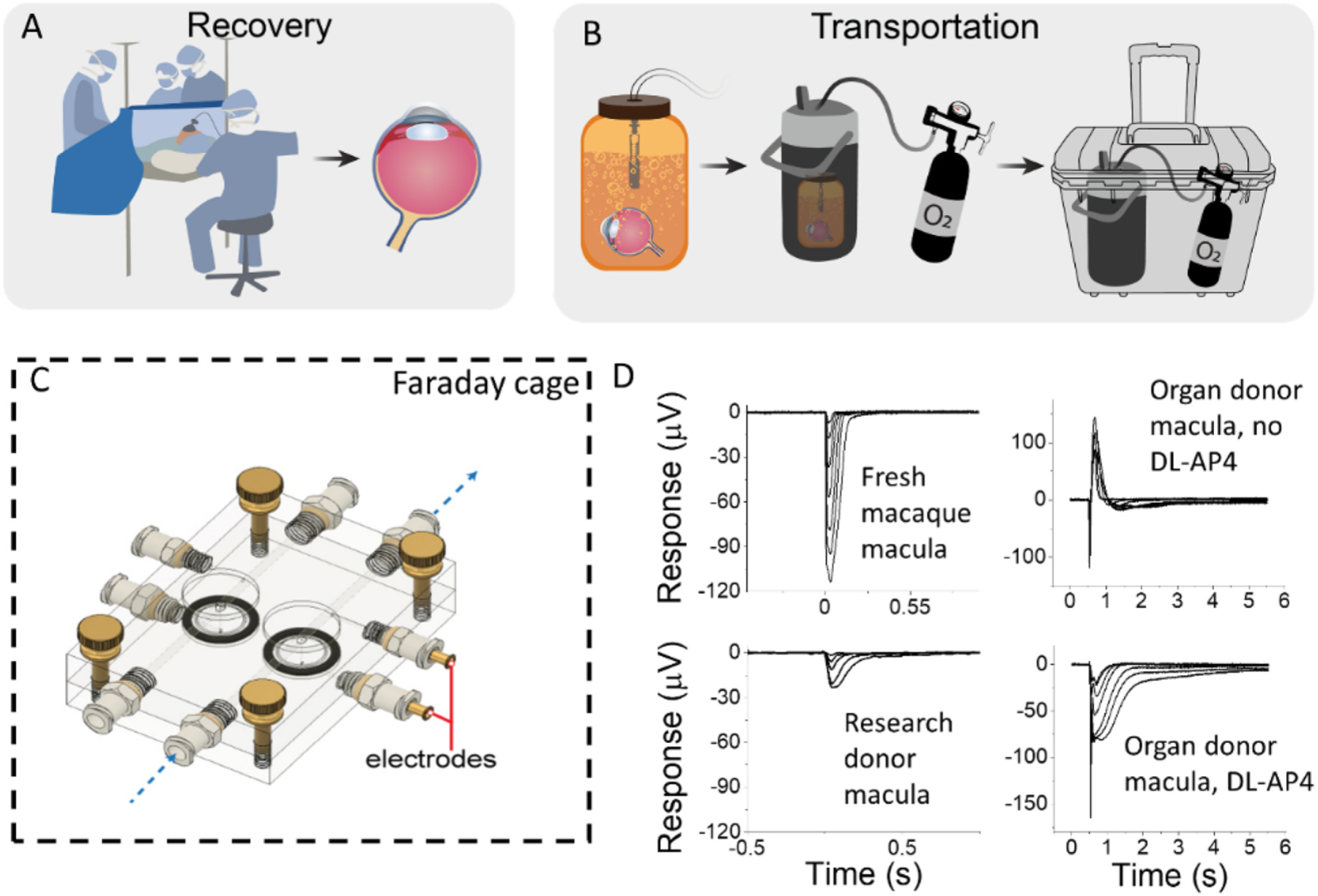

2. Modeling multifactorial age-related eye disease in animals

Suitable animal models help us understand retinal diseases and allow the development of effective treatments. Mouse and other animal models of inherited retinal degenerative diseases (IRDs, recently reviewed in (Moshiri, 2021)), have given us profound mechanistic insight and have recently resulted in a successful, FDA-approved gene therapy for retinal dystrophies due to two mutations in the RPE65 gene (Russell et al., 2017), with many other potential treatments in late-stage clinical trials (NCT00999609, NCT03913143, NCT04855045, NCT05158296, NCT04671433, NCT04794101, NCT03153293, NCT04912843). In stark contrast, AMD and glaucoma lack animal models that faithfully recapitulate the multifactorial mechanisms and full patient phenotypes, thus hindering our ability to develop effective treatments. Cultured human cells, cell lines, organoids and tissues from human donor eyes, which will be discussed in Chapter 7, have been intensely investigated in the past two decades for their potential to replicate retinal disease, since they maintain genetic and many epigenetic traits that contribute to donors’ diseases, avoid inter-species differences in animal experiments, minimize costs and can be relatively easy to use. However, in vitro and ex vivo studies do not account for complex systemic influences that impact disease development and progression, nor do they allow us to study age- and lifestyle-dependent disease processes or help us understand how treatments affect the whole organism.

Many animal models of AMD or glaucoma reproduce symptoms and disease traits without mimicking their root causes in a process known as phenocopying. To gain mechanistic understanding in a simplified system, researchers have introduced genetic mutations and developed acute injury models, which we will discuss below (Cameron et al., 2020; Frank et al., 1989; Kim et al., 2016; Li et al., 1999; Marc et al., 2008; Miller et al., 1986; Noell et al., 1966; Organisciak and Vaughan, 2010; Urcola et al., 2006; Woodell et al., 2013). These simpler models will necessarily fall short, however, when we try to understand the age-dependent progression of a complex disease with overlapping contributions from multiple risk factors (Figs. 2 and 5) and predict the success of new therapies in patients.

Fig. 5.

The major modeling strategies of AMD (A) and glaucoma (B) based on genetic variants (purple), environmental/lifestyle stressors (green) and pathological pathways (yellow).

Small animal models, such as mice or zebrafish, have been widely employed in in vivo studies, particularly when investigating monogenetic IRDs, since they can be genetically modified comparatively easily, reproduce with a short gestation time and are cheap to maintain. On the other hand, these animals have a short life span of only up to two years and they may not faithfully model cellular insults and disease progression due to lifestyle and environmental factors that accumulate in human patients with AMD and glaucoma for 65 years or more. Rabbits have a long history in ophthalmological research from IRD (Jones et al., 2011b) to glaucoma (Gherezghiher et al., 1986; Johnson et al., 1999; Seidehamel and Dungan, 1974) with strong potential for researchers to leverage them more heavily. Non-human primate (NHP) models can often fill the gap between small mammals and humans, although this research is expensive, fraught with ethical concerns and currently lacks the versatile genetic tools and disease models available in mice and zebrafish. Research into AMD and glaucoma, therefore, mainly relies on small mammals, on which we will focus in this review. However, it is important to understand that as one of their main disadvantages small mammals such as mice, rats or rabbits lack a key anatomical feature, namely the macula, which is primarily affected in AMD. Therefore, we will also briefly discuss prospects for large animal models, retina organoids and donor human eye tissues in Chapter 7.

3. Mouse models based on major genetic risk factors in AMD and glaucoma

Early reports concluded that genetics play an overwhelming role in AMD and glaucoma based on their high concordance in monozygotic twins (Gottfredsdottir et al., 1999; Grizzard et al., 2003; Meyers et al., 1995; Meyers and Zachary, 1988; Teikari, 1990). Since then, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have linked 52 variants across 34 loci with AMD (Fritsche et al., 2013, 2016) (Fig. 6). The broad range of genes associated with AMD indicates that multiple pathways may be implicated in disease initiation and progression. These include the complement pathway (CFH-CFHR1–5, CFB, CFI, C2, C3, and C9), lipid metabolism and transport pathways (APOE, LIPC, CETP, and BAIAP2L2), angiogenesis (VEGFA, TGFBR1, ADAMTS9, MMP9), the vitamin A cycle, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and degradation (COL8A1, COL10A1, TIMP3, ADAMTS9, TGFBR1, HTRA1, and B3GALTL) and cell survival, oxidative stress response, apoptosis and DNA repair (ARMS2, RAD51B, and TNFRSF10A) (Fritsche et al., 2016; Pool et al., 2020). Variants and haplotypes associated with the chromosome 1q32 and 10q26 regions account for approximately 70% of disease variability explained by additive genetic effects (see Fig. 7), while the remaining 32 associated loci contribute comparatively little to disease course and outcome (Fritsche et al., 2014; Fritsche et al., 2016), making it, therefore, difficult to determine their respective differential effect on disease. Because of their prominence in AMD etiology, this review focuses on mechanisms associated with the 1q32 and 10q26 loci.

Fig. 6. Manhattan plot taken with permission from Fritsche et al., 2016 showing the fifty-two independent variants across 34 loci independently associated with AMD through genome-wide association studies.

The two most common contributors to disease are the CFH-CFHR5 region on chromosome 1q32 and the ARMS2/HTRA1 locus on chromosome 1q26. Other variants have a comparatively smaller effect on disease outcome.

Fig. 7.

A large part of the population-attributable risk for AMD can be traced to risk at the CFH-CFHR5 or ARMS2/HTRA1 loci, smoking and BMI. Additional factors including minor AMD-associated variants, hypertension, diet and light exposure have a comparatively smaller contribution to disease.

Conversely, when considered individually, each of the more than 120 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have been associated with glaucoma (Gharahkhani et al., 2021), increased IOP, vertical cup-to-disc ratio, central corneal thickness, cup area and disc area only marginally increase disease risk and the mechanisms by which these genetic variants cause glaucoma onset and progression remain poorly understood (Liu and Allingham, 2017). Polygenic risk scores (PRS), which combine the effect of variants associated with an increased risk for developing glaucoma into a single score, have a limited ability to predict the onset of the disease. Although individuals at highest risk with a PRS in the top decile have a 15-fold increased risk of developing advanced glaucoma as compared to the bottom decile, the PRS decile does not strongly correlate with mean age at diagnosis and surviving proportion of baseline retinal nerve fibre layer (Craig et al., 2020). To avoid exhaustive lists, we will review only a selection of genetically engineered mouse models for the major known genetic risk variants for AMD and glaucoma and instead focus on strategies to model these complex diseases.

3.1. Complement factor H (CFH) in AMD

Complement factor H (CFH), a key regulator of the alternative pathway of the complement system, has been heavily researched since it was identified as the first gene associated with AMD in 2005. By secreting proteins encoded by the CFH gene, factor H (FH) and its splice variant factor h-like protein 1 (FHL-1), the RPE prevents intraocular complement activation from the systemic circulation and, therefore, maintains the eye’s immune-privileged status. Polymorphisms of CFH and the highly homologous complement factor H-related (CFHR) gene family on chromosome 1q32 can confer either risk for or protection from AMD (Pappas et al., 2021). All common CFH-CFHR5 risk haplotypes contain a polymorphism encoding a tyrosine to histidine substitution at position 402 (Y402H) of FH and FHL-1 (Hageman et al., 2005), which affects approximately 55% of AMD patients in the United States. Refined genetic association analyses have shown that the spectrum of AMD susceptibility associated with the 1q32 locus ranges from protection to neutrality and risk, with odds ratios for developing AMD among individuals carrying combinations of CFH-CFHR5 risk and neutral haplotypes from 1.7 to 2.9. Haplotypes associated with protection against the development of AMD mitigate risk haplotypes in a 1-to-1 manner (Pappas et al., 2021; Zouache et al., 2024). These relatively small odds ratios indicate that other genetic and/or environmental risk factors likely contribute to the onset and progression of the disease.

Many of the mechanisms by which FH/FHL-1 Y402H substitution increases AMD risk are well described: Reduced binding of mutant CFH to C-reactive protein (CRP) upregulates the cytokines interleukin-8 and CCL2 and thus potentially increases inflammatory damage (Giannakis et al., 2003), while reduced binding to oxidized phospholipids and malondialdehyde, a common lipid peroxidation product, may exacerbate oxidative stress (Shaw et al., 2012; Weismann et al., 2011). In addition, FH/FHL-1 Y402H substitution overactivates the complement pathway, explaining the deposition of complement proteins in the region of Bruch’s membrane and increased drusen formation (Giannakis et al., 2003; Magnusson et al., 2006; Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2010). Aged CFH-deficient (Cfh−/−) mice partly recapitulate these phenotypes, with only autofluorescent subretinal deposits that resemble lipofuscin (Fig. 8) and complement C3 accumulation (Anderson et al., 2002a) in the neural retina generally observed. While deformed and degenerated photoreceptor outer segments in Cfh−/− mice likely explain their decreased light response amplitudes and visual acuity, Coffey et al. did not observe appreciable photoreceptor loss, indicating that lack of CFH alone does not cause late-stage AMD (Coffey et al., 2007). Similarly to patients with AMD, environmental stressors, such as high-fat cholesterol-enriched diet, smoking or hydroquinone, a major component of cigarette smoke, markedly accelerate and exacerbate AMD-like pathology in Cfh+/− mice or Cfh−/− mice with mutated human CFH Y402H (Aredo et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2022; Landowski et al., 2019), while a high-fat cholesterol-enriched diet reduces light response amplitudes in mice expressing human CFH Y402H (Fig. 3C, from (Landowski et al., 2019)).

Fig. 8. Autofluorescence deposits in Cfh−/− mouse retinas.

From (Coffey et al., 2007).

3.2. High-temperature requirement factor A1 (HTRA1) and age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2 (ARMS2) in AMD

Although AMD was found to be associated with the age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2 (ARMS2) and high-temperature requirement factor A1 (HTRA1) genes at locus 10q26 only after CFH-CFHR5 had been identified, their higher penetrance impacts individuals substantially more. Sixty-four percent of patients with late AMD carry an ARMS2/HTRA1 risk allele and homozygous individuals have odds ratios of 8.6 for developing GA and 11.2 for neovascular AMD (Thee et al., 2022). Due to strong linkage disequilibrium, i.e., the non-random association of closely positioned genes on the same chromosome during meiosis, at the 10q26 locus (Jakobsdottir et al., 2005; Rivera et al., 2005), the disease-causing gene(s) or variant(s) of ARMS2 and HTRA1 cannot be resolved through GWAS studies, making the differential contribution of these two genes and associated encoded proteins in the pathophysiology of AMD controversial. NHPs, such as rhesus monkeys, possess ARMS2 and HTRA1, variants of which are associated with soft drusen as an indicator of AMD pathology (Francis et al., 2008). However, since the linkage disequilibrium within these genes in monkeys is reduced compared to humans, the different gene structure of this region in NHPs indicates that they may not represent a good model organism to determine AMD-causal variants and elucidate underlying mechanisms.

Variant rs1049024 in exon 1 and an insertion-deletion (del443ins54) in the 3’ untranslated region of ARMS2 demonstrate that SNPs in both coding and non-coding regions contribute to AMD risk (Pan et al., 2022). Only recently have analyses carried out among individuals with rare recombinant haplotypes helped narrow the region associated with AMD risk to a block of SNPs that overlap ARMS2 exon 1 and intron 1 (Grassmann et al., 2017). Recent work performed using a large number of human donor eyes showed that the level of the HtrA1 protein at the primary location of AMD pathology increases with age among individuals with no risk at the 10q26 locus and that this increase is significantly lower among individuals with ARMS2/HTRA1 risk alleles, resulting in significantly lower HTRA1 mRNA levels. Reduced HTRA1 expression is RPE-specific and mediated by a non-coding, cis-regulatory element located in a region almost identical to that identified by Grassman et al. and Williams et al. (Grassmann et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2021). While several investigations have reported that HTRA1 expression and protein levels were in fact higher in patients with AMD, most of these studies, however, did not consider genetic risk status at the 10q26 locus (Merle et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2022). Based on these recent findings, we expect HTRA1 levels to be higher among AMD patients with no risk at the chromosome 10q26 locus as compared to controls.

Reliable detection and localization of the ARMS2 protein in human tissue and cells remain elusive, resulting in many conflicting reports to date (Fritsche et al., 2008; Kanda et al., 2007; Kortvely et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2009). Since mice do not carry the ARMS2 gene and ubiquitous postnatal expression of ARMS2 in aged mice does not confer abnormal retinal phenotypes (Liu and Hoh, 2015) (Table 1), our understanding largely relies on in vitro studies, in which ARMS2 protein localizes to mitochondria (Kanda et al., 2007) and extracellular matrix (ECM) (Kortvely et al., 2010). In a complex with the complement activator properdin, ARMS2 increases C3b surface opsonization, which tags apoptotic and necrotic cells for phagocytosis (Micklisch et al., 2017). Likely due to increased turnover of ARMS2 mRNA (Fritsche et al., 2008), monocytes from patients with two high-risk alleles of the ARMS2 variants rs10490924 and del443ins54 do not express ARMS2 protein (Micklisch et al., 2017), which reduces phagocytosis and cellular debris removal and may increase the risk for drusen deposits over time (Micklisch et al., 2017). Of note, the high-risk del443ins54 and rs10490924 ARMS2 mutations decrease the expression of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD) 2 and SOD activity and thus increase oxidative stress in patient-induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived RPE cells (Chang et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2014), potentially linking these mutations to environmental factors and aging that contribute to AMD pathology (see Chapter 4.1).

Table 1.

Common AMD animal models. Pathologies indicate phenotypes present in each model that are common in human AMD patients.

| Genetic risk models of AMD | Gene of Interest | Model | Pathway | Pathology Autofluorescence | Deposits/plaque | PRC atrophy/changes | RPE atrophy/changes | Reduced ERG | CNV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chimeric CFH tg + hydroquinone/light | Mouse | Complement/oxidative stress | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Human CFH−/− Y402H variant + high fat diet | Mouse | Complement/lipid metabolism | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | |

| CFH+/− + cigarette smoke | Mouse | Complement/oxidative stress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | |

| CFH−/− | Mouse | Complement | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | |

| ARMS2 risk variants | Non-human primates | Transcription factor and oxidative stress | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | N/A | N/A | |

| HTRA1−/− | Mouse | Serine protease and extracellular chaperone | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | N/A | |

| HTRA1 Ubiquitous Overexpression | Mouse | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | ||

| hHTRA1 expression in RPE | Mouse | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | ||

| hHTRA1 expression in PRC | Zebrafish | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | N/A | X | ||

| Human apoE4, high fat-cholesterol diet, aged | Mouse | Lipid metabolism | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ |

Legend.

X Phenotype not present.

✓ Phenotype present.

N/A Unknown phenotype.

ARMS2 not only resides closely to HTRA1, but the del443ins54 ARMS2 mutation also increases HTRA1 transcription by binding Gtf2i-β/δ transcription factors in AMD patient-derived cell lines (Pan et al., 2021). HTRA1 binds various proteins, including transforming growth factor (TGF-β) 2, which regulates angiogenesis (Pan et al., 2021), however, it mainly functions as a secreted serine protease by cleaving several proteins associated with AMD, like retinol binding protein (RBP) 3 which prevents toxic lipofuscin formation around photoreceptors (Tom et al., 2020). HTRA1 also cleaves clusterin, present in soft Drusen from AMD patients (Sakaguchi et al., 2002), vitronectin and fibromodulin that all modulate the complement cascade, as well as other RPE-secreted proteins involved in amyloid deposition (An et al., 2010; Choi et al., 1989). As perhaps one of its most important roles in AMD, HTRA1 cleaves ECM components, such as fibronectin and nidogen 1 and 2, but not laminin, type IV collagen and elastin, resulting in a discontinuous elastic layer of BrM in mice that overexpress murine Htra1 in RPE cells (Vierkotten et al., 2011).

Multiple existing animal models may elucidate some of the mechanisms by which HTRA1 contributes to AMD (Table 1): In line with its role as a serine protease that cleaves ECM proteins, overexpression of mouse Htra1 in the entire body (Nakayama et al., 2014) and human HTRA1 in RPE cells (Nakayama et al., 2014) caused choroidal neovascularization, likely by degrading the elastic lamina of BrM and compromising underlying choroidal blood vessels (Jones et al., 2011a; Kumar et al., 2014). Considering that genetic risk variants that increase HTRA1 expression in patients are associated with neovascular AMD, particularly the transgenic mice that selectively overexpress HTRA1 in the RPE described by Jones et al. and Kumar et al. represent promising models to investigate polypoidal choroid vasculopathy (Jones et al., 2011a; Kumar et al., 2014), an anti-VEGF resistant form of neovascular AMD (Gomi et al., 2008; Kokame et al., 2010). While overexpression of human HTRA1 in zebrafish photoreceptors accumulates lipofuscin and induces photoreceptor cell death (Oura et al., 2018), RPE cell loss may be abrogated since this species not only repairs full thickness retinal injury, but also regenerates RPE, likely from remaining RPE cells (Hanovice et al., 2019). Htra1 knockout mice develop strong retinal phenotypes with loss of photoreceptors and RPE dysfunction according to a recent conference abstract, but no peer-reviewed paper has been published yet that describes this model (Biswas et al., 2022).

3.3. Myocilin (MYOC) in glaucoma

Of the currently four genes specifically associated with Mendelian inheritance of glaucoma, myocilin, WDR36, optineurin, and TBK1, we have chosen to discuss the former in detail for this review. Myocilin (MYOC) mutations as one of the major genetic risk factors for glaucoma were first identified as a causative element in patients with juvenile open-angle glaucoma (JOAG) and subsequently associated with POAG in at least two families (Alward et al., 1998; Stone et al., 1997). Approximately 70 MYOC mutations link to various forms of glaucoma (http://myocilin.com/) and with a prevalence of 3–5 % among adult-onset patients they form the most common form of inherited glaucoma (Alward et al., 1998; Stone et al., 1997; Suzuki et al., 1997), some of which associate with familial forms of glaucoma, including TYR437HIS and ILE477ASN (Alward et al., 1998). While the function of MYOC currently remains unknown, most tissues of the body, including ocular tissues, trabecular meshwork (TM), ciliary body, retina, sclera, cornea, lens and vitreous, express this protein (Adam et al., 1997; Karali et al., 2000; Kubota et al., 1997; Ortego et al., 1997; Swiderski et al., 2000; Wang and Johnson, 2000). As a component of aqueous humor (AH), secreted MYOC circulates throughout the anterior segment and thus reaches all tissues in the conventional outflow pathway (Russell et al., 2001). Although glucocorticoids increase MYOC expression, no “classic” glucocorticoid response element (GRE) sequences were found in the MYOC promoter (Fingert et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 1998), but they contain multiple GRE “half-sites” with similar sequences that bind glucocorticoid receptors and mediate delayed responses to steroids (Chan et al., 1991), which may induce MYOC protein expression in cultured human TM cells (Shepard et al., 2001) and thus provide a mechanism by which glucocorticoids can induce glaucoma.

Two main hypotheses have been put forward to explain the role for MYOC in glaucoma pathogenesis: 1) overproduced and secreted MYOC may accumulate within the TM and increase outflow resistance (Polansky et al., 1997) or 2) mutations may decrease MYOC secretion from TM cells, which accumulates in cellular secretory compartments (Caballero et al., 2000). While MYOC perfused into human anterior segments increases the outflow resistance and, therefore, IOP (Fautsch et al., 2000) and spontaneously elevated IOP and glaucoma are associated with increased MYOC in rats and canines (Hart et al., 2007; MacKay et al., 2008a; Mackay et al., 2008b; Naskar and Thanos, 2006), reverse findings in human cells and tissues complicate the issue. Primary human TM cells release less mutant compared to wildtype MYOC (Caballero et al., 2000; Jacobson et al., 2001) and the AH in glaucoma patients contains no detectable mutant MYOC Q368X (Jacobson et al., 2001). Conversely, increased MYOC in the TM of glaucoma patients (Lutjen--Drecoll et al., 1998) suggests that the protein, especially when misfolded, overexpressed and aggregated in the endoplasmic reticulum, initiates a response to remove the misfolded protein from the cells’ secretory machinery (Liu and Vollrath, 2004; Wang and Kaufman, 2016). While in non-diseased cells autophagy can clear wildtype MYOC buildup (Aroca-Aguilar et al., 2005; Qiu et al., 2014), dysregulated glaucomatous TM cells likely accumulate mutated MYOC in the secretory pathways (Aroca-Aguilar et al., 2005; Jacobson et al., 2001; Porter et al., 2015), causing ER stress and ultimately resulting in cell death and tissue degradation (Liu and Vollrath, 2004; Wang and Kaufman, 2016). In addition, mutant MYOC also causes intracellular accumulation of ECM proteins such as fibronectin, elastin and type IV collagen due to ER stress caused by misfolded MYOC (Kasetti et al., 2016). Due to this multitude of experimental evidence the second hypothesis that mutant MYOC variants aggregate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), creating ER stress and causing cell death, has become widely accepted.

The importance of MYOC in glaucoma led Senatorov et al. to develop a mutant mouse with the same Tyr423His point mutation seen in humans (Senatorov et al., 2006) (Table 2), which associates with the most severe forms of glaucoma and a younger age of onset. While the TM and sclera in both wildtype and transgenic mice expressed MYOC, it was consistently found at elevated levels in the TM of transgenic mice, which also displayed increased IOP compared to wildtype at 12–18 months of age. By 12–20 months the optic nerve of transgenic mice was damaged, with increased GFAP expression, patches of “empty” space and dark axonal profiles and ~20 % loss of RGCs in the peripheral retina. While we do not necessarily understand how mutated MYOC increases IOP, degenerates the optic nerve and causes RGC death, these changes in transgenic mice are consistent with POAG progression in humans, making Tyr423His Myoc mice and effective animal model to study glaucoma.

Table 2. Common genetic animal models in glaucoma.

Pathology indicates phenotypes present in animal models characteristic of glaucoma. IOP, intraocular pressure, RGCs, retinal ganglion cells.

| Genetic models of glaucoma | Gene of Interest | Model | Pathway | Pathology Elevated IOP | Degenerating RGCs | Decreased retinal function | Reduced RGC number | Reduced retinal thickness | Optic nerve changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tyr423 His Myoc | Mouse | Myocilin mutation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | |

| LOXL1−/− | Mouse | Elastosis | ✓ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ✓ | |

| 9p21 locus−/− | Mouse | Cell cycle progression | X | X | ✓ | X | N/A | ✓ |

Legend.

X Phenotype not present.

✓ Phenotype present.

N/A Unknown phenotype.

3.4. Lysyl oxidase-like 1 (LOXL1) in glaucoma

In addition to the above mentioned MYOC, WDR36, optineurin and TBK1, which cause monogenic glaucoma, a number of genes have been associated with the disease through genome-wide association studies. Although an exhaustive list would exceed the scope of this review, we have included several of these genes in Table 2 and will discuss lysyl oxidase-like 1 (LOXL1) and the 9p21 locus (below) as important examples in detail. First discovered in a GWAS by Thorleifsson et al. (2007), mutations in LOXL1 are associated with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (XFG), a subtype of open-angle glaucoma. While the specific responsible genetic variants remain under investigation, numerous identified SNPs are associated with decreased or increased risk depending on the variant (Eliseeva et al., 2021) and can even differ among ethnic populations (Chen et al., 2009, 2010; Fuse et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Ramprasad et al., 2008; Rautenbach et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2010). Thus far, the causative element of the LOXL1 gene in glaucoma remains unknown and studies to examine whether non-coding regions, such as those encoding long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), regulate LOXL1 expression are underway (Hauser et al., 2015; Schmitt et al., 2023).

The lysyl oxidase family comprises enzymes that regulate, synthesize and maintain elastic fibers (Csiszar, 2001; Kagan and Li, 2003), as demonstrated by the strong colocalization of LOXL1 with elastin (Liu et al., 2004). Differing reports of LOXL1 expression in patients with XFG, ranging from increased protein in the AH (Greene et al., 2020) to reduced mRNA in ocular tissues (Pasutto et al., 2017), may be reconciled by the observation that LOXL1 expression depends on the disease stage, with early increased LOXL1 in ocular tissues which declines in advanced disease (Schlotzer-Schrehardt et al., 2008). LOXL1 likely contributes to IOP control, since knockout mice with severe elastic tissue abnormalities (Liu et al., 2004) exhibit a strong ocular phenotype with decreased ocular compliance, increased AH outflow capacity and possibly increased episcleral venous pressure that prevents collapse of Schlemm’s Canal (SC) during acute IOP elevation (Li et al., 2020). The phenotype of LOXL1−/− mice depends on their genetic background (Schmitt et al., 2021; Suarez et al., 2022), which will surely lend fundamental insight into the human genes that confer susceptibility to XFG. Future studies that develop mouse lines with specific risk haplotypes rather than complete knockouts would allow researchers to specifically determine the pathophysiological pathways affected within the eye.

3.5. 9p21 locus in glaucoma

In addition, GWAS in glaucoma patients have identified multiple SNPs at locus 9p21.3 (Ng et al., 2014), initially in a European and an American Caucasian cohort and subsequently across different continents. On chromosome 9p21 the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKN) 2A and CDKN2B genes lie adjacent in a region known as the Ink4 locus and encode tumor suppression proteins that inhibit cell cycle progression (Hannon and Beach, 1994; Ng et al., 2014; Seoane et al., 2001), including TGFβ, an important cytokine in glaucoma pathogenesis (reviewed e.g. by (Prendes et al., 2013)) that upregulates CDKN2B. A lncRNA, known as CDKN2B-AS, overlaps CDKN2B and is transcribed in the opposite direction, but thus far its function remains elusive. Interestingly, the glaucoma-associated SNPs reside in the lncRNA CDKN2B-AS or its introns, indicating that this lncRNA plays a role in glaucoma pathogenesis, likely by influencing RNA expression levels and splicing patterns (Burd et al., 2010; Wiggs et al., 2012).

Variants in the Ink4 locus could conceivably contribute to glaucoma pathogenesis through several mechanisms: Since TGFβ upregulates CDKN2B, while CDKN2B-AS silences transcription within the Ink4 locus, rendering both molecules antagonists, dysregulated CDKN2B-AS could increase expression of CDKN2B and thus increase susceptibility of RGCs to apoptosis (Ng et al., 2014). In addition, CDKN2B-AS may regulate genes outside of the Ink4 locus that influence RGC function and fate. SNPs in this locus may also affect transcription factor binding independently of CDKN2B and/or CDKN2B-AS (Hannou et al., 2015; Harismendy et al., 2011) or affect post-transcriptional regulation of RNA (Zhang et al., 2014). Visel et al. created a transgenic mouse model to investigate a 70 kb deletion in the murine equivalent of the 9p21 locus, which lacks three exons in the murine counterpart of CDKN2B-AS (Zheng et al., 2013). Although the retina functions as normal with typical histological morphology in heterozygous and homozygous CDKN2B-AS knockout mice, glial cells in the retina and optic nerve head were activated and IOP elevation resulted in greater loss of RGCs in homozygotes (Gao and Jakobs, 2016).

4. Modeling pathological pathways in AMD and glaucoma

While GWAS have identified numerous gene variants associated with AMD and glaucoma, the mechanism(s) by which high or low-risk alleles modify the probability of these diseases developing and progressing remain unclear. AMD and glaucoma likely represent multifaceted diseases in which multiple unknown molecular changes converge on a common, clinically observable pathophysiology. In other words, individual patients are likely to experience AMD and glaucoma due to different underlying causes, making it impractical to study one model system that recapitulates all the known hallmarks of both eye diseases. On the other hand, changes to the same downstream processes in the eye contribute to AMD and glaucoma pathology, even if their link to human genetic risk factors remains unknown or can only be speculated. This has resulted in the development and use of animal models that phenocopy pathways implicated in AMD and glaucoma to study specific aspects of the disease (Tables 3, 4 and 5), sometimes in transgenic animals with mutations that have never been found in patients, but which, nevertheless, offer valuable information about pathobiological mechanisms. In this chapter, we will review the main pathological pathways and animal models used to study their role in AMD and glaucoma.

Table 3.

Genetic models of AMD that phenocopy pathological pathways in human patients.

| Oxidative stress models of AMD | Gene of Interest | Pathway | Pathology Autofluorescence | Deposits/plaque | PRC atrophy/changes | RPE atrophy/changes | Reduced ERG | CNV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sod1−/− mice | Superoxide breakdown | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | |

| Sod1−/− Park7−/− Prkn−/− mice | Superoxide breakdown | N/A | ✓ | N/A | N/A | ✓ | N/A | |

| Sod2 RPE knockdown mice | Superoxide breakdown | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | |

| MEFD+/− mice + light | Antioxidant gene expression | N/A | N/A | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | N/A | |

| Nrf2−/− mice + light | Antioxidant gene expression | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | |

| Abca4−/− Rdh8−/− | Compromised all-trans-retinal clearance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Legend.

X Phenotype not present.

✓ Phenotype present.

N/A Unknown phenotype.

Table 4.

Genetic models that link oxidative stress with retinal ganglion cell loss due to excitotoxicity.

| Oxidative stress models of glaucoma | Gene of Interest | Species | Pathway | Pathology IOP elevation | RGC loss | Glial cell activation | Altered mitochondrial fission/fusion | Optic nerve degeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPAenu/+ | Mouse | Mitochondrial inner membrane structure | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | |

| GLAST−/− | Mouse | Glutamate transporter | X | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | |

| EAAC1−/− | Mouse | Glutamate transporter | X | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ |

Legend.

X Phenotype not present.

✓ Phenotype present.

N/A Unknown phenotype.

Table 5.

Genetic models that connect ECM changes with glaucoma.

| ECM models of glaucoma | Gene of Interest | Species | Pathway | Pathology IOP elevation | Decreased outflow capacity | RGC loss | Optic nerve degeneration | Increased ECM protein expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col1a1r/r | Mouse | Collagen hydrolysis inhibition | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | N/A | |

| SPARC−/− | Mouse | ECM synthesis, collagen regulation | X | X | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Col4a1 C57/BL6 | Mouse | Basement membrane components | X | N/A | X | X | N/A | |

| Col4a1 129B6 | Mouse | Basement membrane components | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | |

| PTP-Meg2 (−/+) | Mouse | Tyrosine-phosphatase | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Legend.

X Phenotype not present.

✓ Phenotype present.

N/A Unknown phenotype.

4.1. Modeling oxidative stress in AMD

The retina provides a unique environment that favors reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Beatty et al., 2000) due to multiple factors: the retina consumes vast quantities of oxygen, even compared to the brain (Carlisle et al., 1964), contains polyunsaturated fatty acids that readily oxidize and photosensitive molecules such as rhodopsin and directly experiences light, including short wavelengths which inflict tissue damage (Ham et al., 1976). Multiple observations have long linked AMD with oxidative stress, including higher AMD risk in current and former smokers (Clemons et al., 2005; Klein et al., 1998; Mitchell et al., 2002), mildly protective effects of antioxidant vitamins and minerals in the AREDS and AREDS2 supplements which slow the advance of AMD (AREDS2 Research Group, 2012; Chew et al., 2022; Chew et al., 2013), and higher levels of the macromolecular oxidative damage markers malondialdehyde, protein carbonyl and 8-OHdG in the serum from patients with neovascular AMD (Totan et al., 2009). In fact, aging of the body increases oxidative stress and reduces antioxidant defense mechanisms (Zhang et al., 2015), which may at least in part explain the age dependency of AMD.

Many genetic mouse models that increase oxidative stress target antioxidant proteins (Table 3), such as SOD, although some studies also affect the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (NRF2) transcription factor that regulates the expression of various antioxidant proteins, including SOD and its upstream activator myocyte enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D). Photoreceptors in homozygous Mef2d knockout mice fail to develop outer segments and eventually degenerate (Andzelm et al., 2015; Omori et al., 2015), but retinas from haploinsufficient Mef2d+/− mice with otherwise normal retinal morphology express approximately 50 % less MEF2D protein, rendering their retinas more susceptible to oxidative stress. A single dose of low light exposure to induce oxidative stress no longer increases Nrf2 transcription and protein translation in Mef2d+/− mice, reducing the expression of multiple antioxidant genes, including all forms of SOD, and resulting in photoreceptor apoptosis (Nagar et al., 2017). Similarly, Nrf2−/− mice lose photoreceptors following light exposure (Wang et al., 2019), but since Nagar et al. mainly evaluated transcription factors and expression of their downstream targets, whereas Wang et al. focused on retinal structure and both studies overlap only when showing reduced photoreceptor light responses, it remains unclear which phenotype is more severe and whether other transcription factors besides MEF2D contribute to light-induced NRF2 activation. Although it takes over a year for symptoms to develop naturally in these mice, it is noteworthy that, like patients who require multiple insults to develop AMD, a diminished antioxidant response combined with light as an environmental insult considerably accelerates AMD-like morphology with subretinal deposits and lesions due to RPE and photoreceptor loss (Wang et al., 2019). In addition, deletion of PGC-1α, a transcription factor that controls mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration, in Nrf2−/− mice also leads to dry AMD-like phenotype including RPE degeneration and loss of photoreceptor function (Felszeghy et al., 2019).

SOD1 or Cu–Zn SOD-deficient (Sod1−/−) mice are more susceptible to oxidative damage, as SOD1 is a major antioxidant enzyme that eliminates superoxide and accounts for most of the SOD activity in the retina (Behndig et al., 1998; Valentine et al., 2005). Aged Sod1−/− mice, one of few available AMD models with both drusen (Fig. 9) and CNV, exhibit, thinning of the RPE, compromised integrity of the RPE barrier, thickening of Bruch’s membrane and CNV at approximately 10 months of age, with light exposure in at least five-month-old mice inducing drusen earlier (Imamura et al., 2006). The Sod1−/− DJ-1(Park7)−/− Parkin (Prkn)−/− triple knockout mouse, which also targets the antioxidant, transcriptional regulator and molecular chaperone PARK7 as well as Parkin, a ubiquitin ligase that marks proteins for degradation, significantly shortens the time until it develops drusen by three to six months, accumulation of microglia and thinning of the RPE at nine months and compromised retinal light responses at one year of age (Zhu et al., 2019). Injection of adeno-associated virus targeting SOD2 or manganese-dependent SOD in RPE cells accelerates the appearance of symptoms to approximately 4.5 months and may represent a more convenient model to study signs of AMD, such as drusen-like deposits, RPE atrophy and increased BrM thickness. These mice also develop photoreceptor disorganization and attenuated photoreceptor responses on electroretinogram, which allow researchers to study disrupted photoreceptor function and structure that normally occur late in AMD (Justilien et al., 2007). An important AMD mouse model combines deletion of two enzymes, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A, member 4 (ABCA4) and retinol dehydrogenase 8 (RDH8), that rapidly clear all--trans-retinal from the retina. Abca4−/− Rdh8−/− mice accumulate all--trans-retinal in the retina, leading to accumulation of toxic conjugate products (Maeda et al., 2009). This model phenocopies most of the AMD pathology, including lipofuscin, drusen, RPE and photoreceptor atrophy, as well as complement activation and CNV (Table 3) and has been used to test efficacy of antioxidative and anti-VEGF drugs for treatment of AMD (Maeda et al., 2009).

Fig. 9. Drusen formation in old Sod1−/− mouse eyes.

Yellowish deposits in fundus photograph (A) and dome-shaped deposit between RPE (*) and Bruch’s membrane (**) (B). (Imamura et al., 2006).

4.2. Modeling oxidative stress in glaucoma

Increased mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage and lipid peroxidation byproducts indicate oxidative stress in patients with glaucoma (Izzotti et al., 2003; Zanon-Moreno et al., 2008). A combination of endogenous and exogenous factors contributes to oxidative stress-induced damage in the anterior segment of the eye: In addition to ROS generated as part of normal metabolism and cell functions in mitochondria, peroxisomes, endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane (Bae et al., 2011; Block et al., 2009; Fransen et al., 2012; Krause, 2004; Nauseef, 2008; Rinnerthaler et al., 2015; Turrens, 2003), light with wavelengths longer than 295 nm passes through the cornea into the anterior chamber (Norren and Vos, 1974), where it can cause oxidative damage. In addition, a higher number of mtDNA mutations in glaucoma patients results in mitochondrial dysfunction with decreased ATP synthesis and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Abu-Amero et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2012). Thus, many in vitro and rodent glaucoma models connect elevated pressure or IOP with mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress through mitochondrial pathways (Ferreira et al., 2010; Ju et al., 2007; Ko et al., 2005; Kong et al., 2009, 2012; Moreno et al., 2004; Tezel et al., 2005).

Oxidative stress can likely alter the morphology and function of the TM outflow pathway and thus increase IOP by affecting ECM structure and accumulation (Knepper et al., 1996a, 1996b), cell-matrix adhesion through the cytoskeleton (Zhou et al., 1999), mitochondrial activity (Clopton and Saltman, 1995), cellular DNA (Izzotti et al., 2011), cell cycle progression (Giancotti, 1997) and apoptosis (Droge, 2002; Frisch and Ruoslahti, 1997), as well as other forms of cell death (Martindale and Holbrook, 2002). Interestingly, increased IOP and visual field defects caused by RGC degeneration in patients with glaucoma correlate with oxidative damage in the TM (Izzotti et al., 2003; Sacca et al., 2005). Taken together, multiple studies indicate that ROS alter the morphology and function of the TM outflow pathway leading to an increase in IOP (Alvarado et al., 1981; De La Paz and Epstein, 1996; Freedman et al., 1985; Gabelt and Kaufman, 2005; Izzotti et al., 2003; Kahn et al., 1983; Kumar and Agarwal, 2007; Sacca et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2006; Wielgus and Sarna, 2008; Zhou et al., 1999).

Several mouse models have also provided a possible mechanism by which oxidative stress may link to RGCs loss (Table 4). Although previous studies questioned whether glutamate excitotoxicity contributes to RGC death in glaucoma (Lotery, 2005), more recent work suggested that it likely plays a role at least in glaucomatous mice (Atorf et al., 2013; Ju et al., 2009). Retinas from OPA1-deficient mice with increased mitochondrial fission experience elevated oxidative stress and upregulate expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors in the RGC layer (Nguyen et al., 2011). Together with the observation that mice lacking the glutamate/aspartate transporter (GLAST) primarily found in Müller glia or the excitatory amino acid carrier 1 (EAAC1) expressed in retinal neurons lose RGCs (Harada et al., 2007), possibly due to decreased glutathione production putting RGCs at risk (Maher and Hanneken, 2005), this suggests that a vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and excitotoxicity via upregulated glutamate receptors may cause RGC death in glaucoma. Intriguingly, a recent clinical study demonstrated that eight rare variants in EAAT1, the human GLAST homologue, are overrepresented in patients with glaucoma, with two loss-of-function variants being more than five-fold more common compared to the control population (Yanagisawa et al., 2020). This observation indicates that, although the glutamate receptor antagonist memantine failed to prevent glaucoma progression in a large-scale clinical trial (Weinreb et al., 2018), a follow up study of the drug specifically in patients with EAAT1 mutations may be worthwhile and that glutamate excitotoxicity in rodents likely represents a relevant model to develop new therapies at least for this small patient population.

4.3. Modeling extracellular matrix (ECM) alterations in AMD

Multiple studies have associated the risks of glaucoma and AMD with mutations in genes that encode extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade ECM or tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs) (Corominas et al., 2018; Desronvil et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2007; Ji and Jia, 2019; Mackay et al., 2015; Vilkeviciute et al., 2019). Highly specialized functions within the eye require different ocular tissues to tightly control the composition and structure of their ECM: As BrM the ECM forms the scaffold for the RPE, through which nutrients, waste products and oxygen diffuse to and from the choroid and which restricts the migration of choroidal and retinal cells. The ECM in the TM regulates the outflow of AH and thus intraocular pressure, while connective tissue in the optic nerve head provides support against mechanical strain from intraocular pressure at the point where RGC axons exit the eye. Instead of coexisting as inert structural support that persists constant throughout life and remains independent from nearby tissues, the ECM closely interacts with its surrounding cells, carries out important signaling functions and changes extensively throughout life and in disease.

BrM lies between the RPE and the choriocapillaris, a fenestrated capillary bed that allows circulating molecules to easily enter the surrounding extracellular space (Fields et al., 2020). Diffusion through BrM depends on many factors, such as hydrostatic pressure, the concentration of diffusing molecules on both sides and the composition and structure of BrM, which affect the availability of e.g., nutrients, lipids, oxygen, vitamins and antioxidant components to the RPE and photoreceptors and the disposal of CO2, water, ions, oxidized lipids and cholesterol and other waste products (Booij et al., 2010). Proteins secreted from RPE and choriocapillaris endothelial cells continuously turn over BrM to ensure its structural integrity and function in the healthy eye (Zouache, 2022).

BrM thickens with both increasing age and in patients with AMD (Ramrattan et al., 1994), while age also changes its composition, e.g., protein (Beattie et al., 2010) and proteoglycan content (Hewitt et al., 1989), deposition of lipids (Beattie et al., 2010), advanced glycation end products (Glenn et al., 2009; Ishibashi et al., 1998) and mineralization (Spraul et al., 1999). As a result, BrM loses much of its permeability to macromolecules throughout life (Moore and Clover, 2001), particularly in the macula (Hussain et al., 2010). Patients with AMD have sustained macular damage that prevents measurements, but permeability of BrM in the periphery is consistently lower than that of donors without AMD (Hussain et al., 2010). These changes may trigger and drive AMD pathology by depriving RPE and photoreceptors of nutrients and oxygen while accumulating waste products may contribute to drusen formation.

Several transgenic mouse models recapitulate genetic variations in the ECM-related proteins TIMP3 and epidermal growth factor-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 (EFEMP1) that GWAS studies have associated with risk in both glaucoma and AMD (Fu et al., 2007; Ji and Jia, 2019; Mackay et al., 2015). The Timp3S179C6/S179C mutation, which is found in several patients with Sorsby Fundus Dystrophy, an inherited macular degenerative disease that encompasses deposits below the RPE and within BrM, GA and neovascularization, decreases inhibition of MMPs, resulting in MMP2 activation and increased neovascularization in laser-induced CNV (Qi et al., 2019), which supports a role of TIMP3, especially in neovascular AMD. Variants in the EFEMP1 gene can cause familial juvenile-onset open-angle glaucoma (Collantes et al., 2022) and the EFEMP1 gene increasingly expresses in retinal-choroidal tissue from patients with AMD, primarily those affected by the neovascular form (Cheng et al., 2020). Although EFEMP1 contributes relatively little risk to AMD, mice with the R345W EFEMP1 mutation develop sub-RPE deposits and buildup of proteoglycans, which diminish diffusion across BrM (Zayas-Santiago et al., 2017). While Timp3S179C6/S179C and R345W EFEMP1 mice may not effectively replicate the complexities of AMD and do not develop many characteristics of the late disease stages, they, nevertheless, represent valuable models of chronic damage to BrM that results in neovascular AMD.

4.4. Modeling extracellular matrix (ECM) alterations in glaucoma

Dysregulated ECM affects two major tissues in glaucoma: the TM in the conventional AH outflow pathway and the lamina cribrosa (LC) at the optic nerve head, which deposits ECM materials in glaucoma. In the TM, the buildup of ECM materials, primarily in the juxtacanalicular region adjacent to SC, increases outflow resistance which elevates IOP (McMenamin et al., 1986; Miyazaki et al., 1987). Glaucoma alters the ECM of the LC in two stages, with initial thickening and posterior migration in early disease (Yang et al., 2011a, 2011b) followed by collapse of the cribriform plates along with increased collagen and elastin deposition (Burgoyne et al., 2005; Hernandez and Pena, 1997; Jonas et al., 2003). A recent study by Reinhard et al. set out to determine how increased IOP changes ECM proteins at the optic nerve head: Mice heterozygous for megakaryocyte protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (PTP-Meg2) exhibit not only chronically and progressively increased IOP through an unknown mechanism, RGC loss and optic nerve damage, but also increased expression of the ECM components fibronectin, laminin and tenascin-C in the optic nerve head (Reinhard et al., 2021).

Multiple transgenic and knockout mouse models (Table 5) illustrate that changes in ECM composition likely contribute to different aspects of glaucoma, with those in the TM elevating IOP by affecting outflow mechanics, although those at the optic nerve head are known, but less well understood. The Col1a1r/r mutation, which confers collagenase-resistance to type I collagen, reduces the outflow capacity for AH, increases IOP and significantly decreases the number of RGC axons in the optic nerves of mice (Aihara et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2009; Mabuchi et al., 2004). Human optic nerve heads from patients with glaucoma increase collagen type IV mRNA and presumably protein biosynthesis (Hernandez et al., 1994), while mice with a heterozygous Col4a1 mutation develop highly variable IOP, including lower IOP in some animals, but, nevertheless, exhibit optic nerve hypoplasia, possibly due to altered composition of the inner limiting membrane (ILM) that stressed the immediately adjacent RGCs (Gould et al., 2007). Interestingly, further studies examining Col4a1 mutations demonstrated a strain-dependent effect, with elevated IOP, RGC loss and optic nerve head degeneration in the 129S6/SvEvTac strain, while CAST/EiJ mice did not develop glaucomatous pathologies (Mao et al., 2015). Conversely, knockout of a matricellular protein called secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), which is highly expressed in the TM and regulates ECM composition, decreases IOP by reducing collagen fibril diameter in the juxtacanalicular region of the TM (Swaminathan et al., 2013).

Constitutively active TGFβ1, which mediates fibrosis, or knockout of MMP9, which degrades ECM proteins to maintain homeostasis, elevate IOP either individually or synergistically in double-transgenic animals (Robertson et al., 2013). The TGFβ signaling pathway may also link these ECM-related changes with cellular senescence: Cultured human TM cells treated with dexamethasone enrich cellular senescence pathways (Li et al., 2023), while TGFβ2 upregulates markers of senescence, possibly through mechanisms involving reactive oxygen species production (Yu et al., 2010). Integrin β3 serves as a cellular ECM receptor (Tietze et al., 1999) with a key role in ECM homeostasis and remodeling in glaucoma in the TM and at the optic nerve head (Filla et al., 2017). Stiffening of the TM due to cellular senescence and/or ECM dysregulation plays a key role in outflow pathology in glaucoma and TM stiffness increases with senescence (Morgan et al., 2015).

4.5. Modeling complement pathway and immune reaction in AMD

The blood-retina barrier grants immune-privilege to the healthy eye (Taylor et al., 2021), with RPE cells secreting immunosuppressants, including CFH that regulates complement activation (Taylor et al., 2021). The identification of CFH mutations as prominent genetic risk factors has highlighted the role of the complement system in disease etiology (Kuchroo et al., 2023), with complement over-activation increasing AMD risk, while complement under-activation protects from AMD (Armento et al., 2021; Heurich et al., 2011; Pappas et al., 2021). The choriocapillaris, which represents the main blood supply for the outer retina, relies mostly on CFH for complement protection (Mullins et al., 2011). Increased accumulation of complement membrane attack complex (MAC) in the choriocapillaris of patients with CFH risk genotypes (Mullins et al., 2011) likely contributes to cytolysis of the choriocapillaris endothelium in early AMD (Mullins et al., 2014), resulting in increased choriocapillaris dropout. Although accumulation of MAC (Mullins et al., 2011) and thinning of the choriocapillaris, especially in the subfovea (Wakatsuki et al., 2015), form a normal part of aging, increased choriocapillaris dropout in patients with CFH risk variants may raise cellular stress from accumulating visual cycle waste products and thus exacerbate immune activation. In addition, the complement system may react to inflammatory components of drusen, such as APOE, C1q, C3, C5 and C5b-9 (Ambati et al., 2013). While the RPE relies on CD46 secretion to protect itself from complement damage, its release diminishes in end-stage AMD, potentially putting RPE cells at risk (Ebrahimi et al., 2013). For a more in-depth understanding of complement system mechanisms and AMD, please refer to other excellent reviews (Armento et al., 2021).

While Ambati et al. suggested that the complement component C5 accumulates in senescent RPE and choroids from mice deficient in the chemokine ligand CCL2 or its receptor CCR2, resulting in a phenotype with many features of AMD, such as lipofuscin and drusen-like deposits, Bruch’s membrane thickening, photoreceptor and RPE degeneration and CNV (Ambati et al., 2003), these findings were not replicated by Luhmann et al. (2009). The observation that CCL2 and CX3CR1 double knockout mice develop drusen-like deposits around 6–9 weeks of age, Bruch’s membrane thickening, photoreceptor and RPE atrophy and CNV (Tuo et al., 2007) was later questioned when this mouse line was found to be contaminated with an Rd8 mutation, in the absence of which mice only showed mild inner retinal changes dissimilar to AMD (Vessey et al., 2012). Lacking accurate small animal models based on aberrant complement activation in AMD, we think that future research with complement models should instead focus on careful description of complement pathway activation in relation to multiple other risk factors to more closely approximate the pathology of AMD. In view of AMD as a chronic disease, in which prolonged immune activation may differ from short-term immune responses to injury, such as laser burns used to induce neovascularization in animal models (Lin et al., 2019), it is, therefore, imperative to closely consider which animal models best represent long-term activation of the complement system in response to environmental stressors, age and genotype risk.

4.6. Modeling ocular hypertension

Common strategies to model glaucoma elevate IOP in animals by artificially decreasing AH outflow and/or intracamerally introducing fluids. Successful early animal models used medium-sized or large species and e.g., injected kaolin into the anterior chamber of rabbits (Voronina, 1954) or α-chymotrypsin into owl monkeys (Kalvin et al., 1966). Technical advancements in small rodent glaucoma models have allowed researchers to increasingly opt for mice and rats as their favored model organisms due to low acquisition and maintenance costs and the additional advantage that mice allow for genetic manipulation. Furthermore, the conventional outflow pathways in mice and rats resemble those in humans, with a wedge-shaped trabecular meshwork consisting of cell-lined trabecular beams, a true, continuous SC and intra- and episcleral vessels (Johnson and Tomarev, 2010; McKinnon et al., 2009; Pang and Clark, 2007). Although the structure of the optic nerve head differs between small rodents and humans, with e.g., mice and rats replacing laminar sheets of connective tissue that support the optic nerve head with a glial lamina (May and Lutjen-Drecoll, 2002; Morrison et al., 1995), they, nevertheless, share many features of glaucoma and the successful development of many IOP-lowering drugs has relied on these animal models.

IOP relies on the equilibrium between the production of AH, which nourishes the cornea and lens and maintains the shape of the eye, and its drainage through the outflow pathways. Thus, IOP can be experimentally elevated by 1) occluding the TM or 2) reducing venous outflow or increasing episcleral venous pressure. The latex microbead model initially developed in the NHP (Weber and Zelenak, 2001) has been adapted to small rodents, in which intracameral injections of polystyrene microbeads physically block outflow pathways in the TM and SC (Chen et al., 2011). Restricting the injected volume to 2 μl in the mouse and 10 μl in the rat minimizes IOP spikes and thus protects the eye from reduced retinal blood flow and ocular injuries during the procedure (Pang and Clark, 2020). Other methods that occlude the TM include physical block of the TM with cross-linked hydrogel (Lin et al., 2022) or destroying the TM tissue by laser photocoagulation (Gaasterland and Kupfer, 1974; Pang and Clark, 2020).

Multiple laboratories have attempted to increase and prolong IOP elevation by varying the bead size, repeating injections or combining them with viscoelastic substances, such as sodium hyaluronate and hydroxypropylmethylcellulose, which reduce reflux when the injection needle is withdrawn and further block the outflow pathways (Chen et al., 2011; Cone et al., 2012; Sappington et al., 2010; Urcola et al., 2006). One method uses magnetic microbeads and magnets placed around the limbus of the eye which allows experimentalists to draw the microbeads from the injection site to the target tissues, thus minimizing loss of the microbeads when the needle is withdrawn and distributing them throughout the TM (Bahrani Fard et al., 2023; Bunker et al., 2015; Ito et al., 2016; Samsel et al., 2011). In these models elevated IOP is sustained for up to 4 weeks, along with RGC loss of ~20–50 % within the same time frame, although both depend on the size and number of introduced microbeads, which allows researchers to tailor IOP increases and expected RGC damage to their needs.

Investigators who wish to study changes in the conventional outflow tissues of the TM and SC in addition to observing glaucomatous changes at the optic nerve head can cauterize episcleral veins or inject hypertonic saline to sclerose them in order to increase AH outflow resistance. Cauterizing episcleral veins elevates IOP for approximately 4 weeks in 87% of the treated mice with 20% RGC loss two weeks after the procedure (Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman, 2006). Sclerosing the veins with saline results in a lesser IOP increase, but similar ~20–50 % loss of RGCs (McKinnon et al., 2003). Since these methods achieve different levels of elevated IOP, it is likely that they rely on different anterior segment responses and should not be used interchangeably (Nissirios et al., 2008). Due to the technical difficulty of sclerosing episcleral veins, this method is used more rarely than cauterization.

Ex vivo cannulation of mouse eyes represents a commonly used method to assess outflow facility and outflow tissue function, which decreases the photopic negative ERG response (Fig. 10C) similar to patients with glaucoma (Fig. 10A and B), although it lacks AH production and episcleral venous pressure (Madekurozwa et al., 2017, 2022; Sherwood et al., 2016). In order to address these limitations, the pressure in mouse eyes can be elevated in vivo, but long-term assessment and precise control of IOP in this procedure to prevent obstruction of blood flow and retinal ischemia remains challenging. Only one device, the iPump by Bello and co-workers (Bello et al., 2017), can monitor IOP over extended periods of time, since it was developed for freely moving rats that undergo cannulation for several months with no signs of significant anatomical or physiological damage while the sensor accurately measures intracameral IOP.

Fig. 10. Photopic negative ERG response (PhNR) in control (A) and glaucoma (B) patient, and in control (black, C) and OHT mouse model (grey, C).

A and B from (Preiser et al., 2013) and C from (Chrysostomou and Crowston, 2013).

In addition to these invasive models, inbred DBA/2J mice spontaneously develop pigmentary glaucoma with elevated IOP caused by compromised ocular drainage (Anderson et al., 2002b, 2008; John et al., 1998). These mice experience RGC death and optic nerve atrophy similar to that observed in human glaucoma patients, although they also develop other pathological symptoms, including corneal calcification and a small iris that complicate in vivo assessment of the ocular phenotypes (Turner et al., 2017), and frequently succumb to early death due to systemic diseases that impedes studying the age-dependent progression of glaucoma.

4.7. Modeling optic neuropathy in glaucoma

At least in animal models of glaucoma, early functional changes and RGC dendrite remodeling likely precede RGC death (Della Santina et al., 2013; El-Danaf and Huberman, 2015; Williams et al., 2016), indicating that these pathological alterations may, therefore, also occur before patients receive glaucoma treatments. Nevertheless, even when patients receive IOP-lowering therapies, they frequently continue to lose vision due to RGC axon degeneration and death, rendering relevant models to study neuroprotection of RGCs critically important (Chang and Goldberg, 2012; Doozandeh and Yazdani, 2016; Gauthier and Liu, 2016; Sena and Lindsley, 2017; Xuejiao and Junwei, 2022). In addition to effects of increased IOP on RGCs, glaucoma as a neurodegenerative disease requires us to also consider the role of the immune system and glial cell activation, similar to other neurodegenerative diseases like AMD and Alzheimer’s disease: Ocular hypertension models (discussed in Chapter 4.6) not only lead to RGC degeneration, but also activate Müller glia, microglia and astrocytes in animal models (de Hoz et al., 2018; Gallego et al., 2012; Guttenplan et al., 2020; Krizaj et al., 2014; Naskar et al., 2002; Schuettauf et al., 2004; Tezel, 2022), while ONHs from patients with glaucoma contained activated microglia (Yuan and Neufeld, 2001).

In order to investigate the pathobiology of optic neuropathy in glaucoma and to test the efficacy and safety of neuroprotective and -regenerative therapies that prevent vision loss independently of IOP elevation, scientists have developed several models that directly injure RGCs in in vivo animal models and compared these to ocular hypertension models described above. The optic nerve can be either crushed or transected without seriously compromising inner retinal circulation (Frank and Wolburg, 1996; Guttenplan et al., 2020; Levkovitch-Verbin et al., 2013a; Tang et al., 2011). Within several days this injury will result in RGC death, astrocyte and microglia activation and changes in RGC gene expression, including upregulation of pro-survival or anti-apoptotic factors (Levkovitch-Verbin et al., 2013a). Alternatively, intravitreal injection of N-methyl-D-aspartate will activate glutamate receptors and cause acute excitotoxicity due to excessive influx of Ca2+ and overactivity of RGCs (Levkovitch-Verbin et al., 2013a).

Both optic nerve crush and intravitreal NMDA injection differ significantly from ocular hypertension models or glaucoma in human patients, since they rapidly cause acute damage compared to long-term low intensity stress in glaucoma or chronically elevated IOP. In addition, the primary injury site of NMDA injection differs from axonal damage, since NMDA receptors mainly localize to RGC dendrites. Side-by-side comparison of these models has shown anti-apoptotic factors to be upregulated only in the retina in the ocular hypertension model, whereas intravitreal NMDA injection and optic nerve crush-induced injury increased pro-survival genes in both the retina and the optic nerve (Levkovitch-Verbin et al., 2013a). Thus, chronic ocular hypertension models might be better suited to understanding the pathobiology of and pre-clinical evaluation of neuroprotective or –regenerative treatments for POAG, while acute RGC injury may serve as a model of normal tension glaucoma.

5. Modeling the effect of environmental and lifestyle factors in AMD and glaucoma

Although genetics play an important role in AMD and glaucoma, explaining >50% of disease variability (Gottfredsdottir et al., 1999; Grizzard et al., 2003; Meyers et al., 1995; Meyers and Zachary, 1988; Teikari, 1990; Zukerman et al., 2021), many people carrying genetic risk factors never suffer from vision disorders despite reaching old age. For example, close to 50% of the population in certain ethnicities carry the CFH Y402H risk variant (Chowers et al., 2008; Edwards et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005; Nazari Khanamiri et al., 2014; Seitsonen et al., 2008; Soysal et al., 2012), but this number vastly exceeds patients with AMD, suggesting that environment and lifestyle play an important role in its pathogenesis (Fig. 7). In comparison, the contribution of environmental factors to glaucoma are far less well understood, but IOP as the only clear modifiable factor in glaucoma can be impacted by external stressors, as discussed below. In this chapter, we will review the current knowledge regarding environmental and lifestyle factors that contribute to AMD and glaucoma and discuss animal models based on exposure to external stressors such as smoking, obesity and poor diet, as well as light exposure.

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) recognized the overwhelming contribution of smoking to the progression of neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy (Clemons et al., 2005), with smokers at greater risk of developing large drusen (Klein et al., 1998) and late AMD at a younger age (Mitchell et al., 2002). Light exposure, high metabolism and the abundance of unsaturated fatty acids naturally predispose the retina to oxidative stress, i.e., an imbalance between reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and protective antioxidants in the body. Harmful chemicals and toxins in cigarette smoke promote AMD at least in part by increasing oxidative stress, whereas the lower abundance of antioxidant proteins in the central compared to the peripheral retina (Velez et al., 2018) likely puts the macula at greater risk of cumulative damage. The observation that the antioxidant AREDS and AREDS2 supplements provide AMD patients with limited protection from progressing to late disease stages (AREDS2 Research Group, 2012; Chew et al., 2022; Chew et al., 2013) strengthens the notion that oxidative stress contributes to AMD.