Abstract

Background:

Women with cardiometabolic pregnancy complications are at increased risk of future diabetes and heart disease which can be reduced through lifestyle management postpartum.

Objectives:

This study aimed to explore preferred intervention characteristics and behaviour change needs of women with or without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications for engaging in postpartum lifestyle interventions.

Design:

Quantitative cross-sectional study.

Methods:

Online survey.

Results:

Overall, 473 women were included, 207 (gestational diabetes (n = 105), gestational hypertension (n = 39), preeclampsia (n = 35), preterm birth (n = 65) and small for gestational age (n = 23)) with and 266 without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications. Women with and without complications had similar intervention preferences, with delivery ideally by a healthcare professional with expertise in women’s health, occurring during maternal child health nurse visits or online, commencing 7 weeks to 3 months post birth, with 15- to 30-min monthly sessions, lasting 1 year and including monitoring of progress and social support. Women with prior complications preferred intervention content on women’s health, mental health, exercise, mother’s diet and their children’s health and needed to know more about how to change behaviour, have more time to do it and feel they want to do it enough to participate. There were significant differences between groups, with more women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications wanting content on women’s health (87.9% vs 80.8%, p = 0.037), mother’s diet (72.5% vs 60.5%, p = 0.007), preventing diabetes or heart disease (43.5% vs 27.4%, p < 0.001) and exercise after birth (78.3% vs 68.0%, p = 0.014), having someone to monitor their progress (69.6% vs 58.6%, p = 0.014), needing the necessary materials (47.3% vs 37.6%, p = 0.033), triggers to prompt them (44.0% vs 31.6%, p = 0.006) and feeling they want to do it enough (73.4%, 63.2%, p = 0.018).

Conclusion:

These unique preferences should be considered in future postpartum lifestyle interventions to enhance engagement, improve health and reduce risk of future cardiometabolic disease in these high-risk women.

Keywords: adverse pregnancy outcome, cardiometabolic disease, cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, intrauterine growth restriction, lifestyle intervention, postpartum, spontaneous preterm birth, women’s health

Introduction

Cardiometabolic pregnancy complications can be defined as maternal and foetal complications experienced during gestation that can contribute to an increased risk of maternal type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) post birth. 1 Their pathophysiology is underpinned by various factors, including impaired hemodynamic adaptation, endothelial and cardiac dysfunction, placental insufficiency, inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance and alterations in glucose metabolism.1 –3 Cardiometabolic pregnancy complications include gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy including preeclampsia (PE), alongside some causes of spontaneous preterm birth (PTB), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and giving birth to a small for gestational age (SGA) infant. Together these affect up to 30% of singleton pregnancies.1,4 Modifiable risk factors for these conditions include high blood pressure, high cholesterol, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, a higher weight, physical inactivity, inadequate nutrition, cigarette smoking and stress.1,2,4 –6

Pregnancy is often referred to as a natural cardiac stress test, as it may unmask underlying risks of suboptimal cardiovascular health. 5 Experiencing a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication presents a sex-specific risk factor for future cardiometabolic disease development 6 and is associated with up to a 10-fold and 2-fold increased risk of T2D 7 and CVD, respectively, in the postpartum period and beyond.8,9 For these women, the postpartum period presents a unique opportunity to provide healthy lifestyle interventions to reduce future cardiometabolic risk.

Current guidelines for managing cardiometabolic pregnancy complications postpartum suggest providing patient-centred, culturally sensitive and practical lifestyle counselling on optimizing diet, exercise and weight and engaging in regular cardiometabolic screening.10,11 However, the postpartum period presents a challenging life stage for many women, representing a time of substantial physical and emotional changes, competing demands and new responsibilities.12 –18 Barriers to adopting a healthy lifestyle for all women postpartum may include lack of knowledge regarding the benefits of lifestyle behaviours, low-risk perception of future lifestyle-related diseases and lack of motivation, time, energy, resources, social support, and individualized and culturally sensitive health advice from healthcare professionals.12 –19 Furthermore, some healthcare professionals may feel they require more training to provide appropriate postpartum lifestyle support. 12 At a system level, there is also a lack of funding for lifestyle interventions. 20 These barriers may contribute to the low levels of intervention uptake in postpartum lifestyle interventions. 21 Our prior systematic review noted participation rates of 0.94%–86% in postpartum lifestyle interventions; however, we acknowledge the limited number of studies included with high-risk populations (4/36), indicating further work is needed in understanding how to support these women. 21

Lifestyle interventions are more effective when using evidence-based theoretical frameworks in design and implementation. 22 For example, the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour (COM-B) system identifies capability, opportunity and motivation as essential factors facilitating behaviour change. 23 The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist provides a comprehensive guide for describing intervention characteristics (e.g. why, what, who, how, where, when and how much) to aid in improving intervention efficacy and replicability. 24 These frameworks are used frequently to inform successful postpartum intervention design15,25 with the TIDieR checklist previously used in identifying intervention characteristics associated with greater postpartum weight loss 25 and the COM-B system in identifying barriers and enablers experienced by women from culturally diverse backgrounds with prior GDM. 15 However, these studies focused on the general postpartum population or women with prior GDM. It is therefore crucial to explore the perspectives and needs of postpartum women with a range of cardiometabolic pregnancy complications to optimize lifestyle intervention content and delivery and improve intervention relevance, uptake and effectiveness.

For women who have experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, understanding what influences behaviour change and preferred intervention characteristics enables development of patient-centred interventions tailored to their wants, needs and preferences. This may consequently increase uptake, engagement, sustainability and behaviour change. Comparing these preferences to postpartum women without prior complications will help identify how these high-risk women could be cared for differently regarding intervention design and delivery. The aims of the study were to explore and compare the interest in, preferred intervention characteristics (based on the TIDieR checklist) and behaviour change needs (based on the COM-B system) of women with or without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications for engagement in a postpartum lifestyle intervention.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a sub-study of a quantitative cross-sectional online survey previously conducted to inform the engagement of postpartum women in lifestyle management. 26 It was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC; Project no. 29273), and all participants provided written informed consent. 26 Detailed methods are previously described elsewhere. 26 The STROBE guideline for cross-sectional studies was followed when preparing the article.

Study participants

Participants were recruited via an external cross-panel market research provider (Octopus group) between 8 November and 21 November 2021. 26 Eligible participants were women aged 18 years and older who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication and delivered their baby in the last 5 years, were not pregnant and were living with their child in Australia. Ineligible participants were women below 18 years of age, who had not delivered a baby within the last 5 years, who were pregnant or were not living with their child in Australia. Women were also excluded who had experienced another health complication which may affect their lifestyle habits or risk of T2D or CVD, specifically diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, infertility or experiencing menopause. Participants were generally a broad representation of the Australian population by location and residence in accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics. 26

Data collection

The survey was self-administered, 20–30 min in duration, consisting of both open format and multiple-choice questions with and without a Likert-type scale response. For this sub-study, the survey questions analysed comprised of a range of questions on the following topics: demographic characteristics (history of cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, age, body mass index (BMI), age of the youngest child, cultural/ethnic background, country of birth, time since migration to Australia (if overseas born), marital status, education, employment, income) and dissemination mode to receive information about lifestyle management (preferred avenue for learning about the programme). Intervention characteristic preferences (according to the TIDieR checklist; preferred programme provider, content, additional inclusions, setting, delivery mode, session frequency, session duration, programme duration) and behaviour change needs (according to the COM-B system; capability, opportunity, motivation; prefaced by: ‘When it comes to you personally participating in a health and wellbeing programme for women after childbirth, what do you think it would take for you to participate in the programme? I would have to. . .’). 26 The survey was developed by the research team. Survey questions relevant to the COM-B system were adapted from the COM-B Self-Evaluation Questionnaire Volume 1. 27 The survey was pilot tested on four women and revised as required before the commencement of data collection. 26

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM Australia Limited, New South Wales, Australia, 2021). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics, dissemination mode, intervention characteristic preferences and behaviour change needs from quantitative data. Categorical data were reported as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data as means and standard deviations for normally distributed data and medians and interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed data. Differences in participant characteristics, choice of dissemination mode, intervention characteristic preferences and behaviour change needs were assessed using an independent sample t-test, Mann–Whitney U test and Pearson’s chi-square test as appropriate, with the significance level set to 0.05, for women with and without a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication. Due to the small sample size of women with cardiometabolic pregnancy complications other than GDM (gestational hypertension; n = 39, PE; n = 35, PTB; n = 65, SGA; n = 23), it was not possible to separately analyse these subgroups. Instead, comparisons were performed by a three-way chi-square test between women who experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication (gestational hypertension, PE, PTB and SGA; n = 105), women who experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication (gestational hypertension, PE, PTB and SGA) without GDM (n = 102) and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication (n = 266). These groups were chosen as there are more established guidelines for pregnancy and postpartum management of GDM. 28 Where there was a significant difference between the three groups, a post hoc test with significance level set to 0.016 (due to three pairwise comparisons being performed, i.e. 0.05/3) was conducted to determine between which of these three groups there was a significance difference.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 473 women, 207 experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication (50.7% GDM, 18.8% gestational hypertension, 16.9% PE, 31.4% PTB and 11.1% had given birth to a SGA infant) and 266 reported having a healthy pregnancy. Of the women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, 157 (75.8%) experienced one, 50 (24.2%) more than one, 42 (20.3%) more than two, 6 (2.9%) more than three and 2 (1.0%) more than four cardiometabolic pregnancy complications. However, 105 (50.7%) women who experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication and the remaining 102 (49.2%) women experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM. Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. Women with a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication had a higher BMI (kg/m2) (27.0 ± 10.4 vs 24.9 ± 8.3, p < 0.001) and were more likely to have a BMI ⩾ 25 kg/m2 (58.9% vs 48.5%, p = 0.022). There was a significant difference in the age of the youngest child (p = 0.009), country of birth (p = 0.011) and employment status (p = 0.034) between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women who experienced or did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication.

| Characteristic | CMPC (n = 207) |

No CMPC (n = 266) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic pregnancy complication | NA | ||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 105 (50.7) | NA | |

| Gestational hypertension | 39 (18.8) | NA | |

| Preeclampsia | 35 (16.9) | NA | |

| Preterm birth | 65 (31.4) | NA | |

| Small for gestational age | 23 (11.1) | NA | |

| Age (years) (M ± SD) | 33.9 ± 5.9 | 33.2 ± 5.3 | 0.158 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (median ± IQR) | 27.0 ± 10.4 | 24.9 ± 8.3 | <0.001 |

| BMI ⩾ 25 kg/m2 | 122 (58.9) | 129 (48.5) | 0.022 |

| Age of the youngest child | 0.009 | ||

| Less than 6 months | 20 (9.7) | 38 (14.3) | |

| 6 months to less than 1 year | 29 (14.0) | 36 (13.5) | |

| 1 year old | 46 (22.2) | 35 (13.2) | |

| 2 years old | 42 (20.3) | 44 (16.5) | |

| 3 years old | 27 (13.0) | 39 (14.7) | |

| 4 years old | 26 (12.6) | 34 (12.8) | |

| 5 years old | 17 (8.2) | 40 (15.0) | |

| Cultural or ethnic background | 0.061 | ||

| Oceanian | 177 (85.5) | 126 (47.4) | |

| European | 5 (2.4) | 13 (4.9) | |

| African | 10 (4.8) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Asian | 60 (29.0) | 95 (35.7) | |

| North American | 1 (0.5) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Latin American | 4 (2.0) | 9 (3.4) | |

| Other | 7 (3.4) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Country of birth | 0.011 | ||

| Australian born | 123 (59.4) | 132 (49.6) | |

| Overseas born | 84 (40.6) | 134 (50.4) | |

| Time since migration to Australia (overseas born), years | 0.937 | ||

| ⩽5 | 24 (28.6) | 43 (32.1) | |

| 6–10 | 28 (33.3) | 48 (35.8) | |

| 11–15 | 14 (16.7) | 20 (14.9) | |

| ⩾16 | 18 (21.4) | 23 (17.2) | |

| Marital status | 0.050 | ||

| Married/de facto | 176 (85.0) | 239 (89.8) | |

| Single (never married/divorced/separated) | 31 (15.0) | 24 (9.0) | |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Education | 0.532 | ||

| Primary/elementary school or less | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Secondary/high school | 56 (27.1) | 64 (24.1) | |

| Diploma/advanced diploma | 43 (20.8) | 49 (18.4) | |

| Degree/higher | 108 (52.2) | 152 (57.1) | |

| Employment | 0.034 | ||

| Unemployed/homemaker | 66 (31.9) | 62 (23.3) | |

| Employed (full-time/part-time/casual) | 130 (62.8) | 148 (55.6) | |

| Studying | 2 (1.0) | 11 (4.1) | |

| Retired | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Government assistance | 6(2.9) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Income | 0.732 | ||

| Low (<AUD$50,000) | 34 (16.4) | 42 (15.8) | |

| Medium (AUD$50,000–AUD$124,999) | 99 (47.8) | 125 (47.0) | |

| High (⩾AUD$125,000) | 59 (28.5) | 87 (32.7) |

CMPC: cardiometabolic pregnancy complication; NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; IQR: interquartile range.

Data are presented as n (%), M ± SD or median ± IQR. Data were analysed using independent samples t-test, Mann–Whitney U test and Pearson’s chi-square test as appropriate.

Dissemination mode to receive information about lifestyle management and intervention characteristic preferences according to the TIDieR checklist

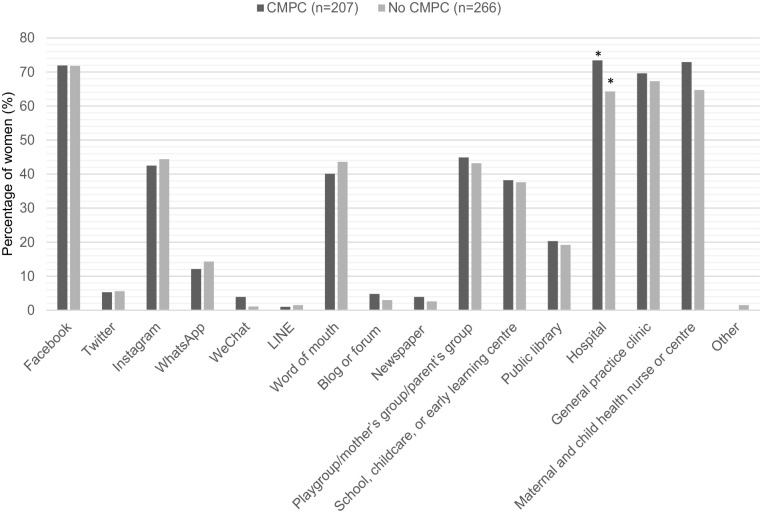

Both women who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication reported being interested in engaging in a postpartum lifestyle intervention (92.8% vs 89.8%, p = 0.297). For women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, the most preferred avenues for learning about an intervention were hospital (73.4%), maternal child health nurse or centre (72.9%) and Facebook (71.9%). Compared to Facebook (71.8%), general practice clinic (67.3%) and maternal child health nurse or centre (64.7%) for those who did not (Figure 1). There was a significant difference between women who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication in hospital as an avenue for learning about a postpartum lifestyle intervention (73.4% vs 64.2%, p = 0.034) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred avenues of women who had or had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication for learning about a postpartum lifestyle intervention. Data are presented as percentages (%). Data were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test.

CMPC: cardiometabolic pregnancy complication.

*Represents a significant difference between groups.

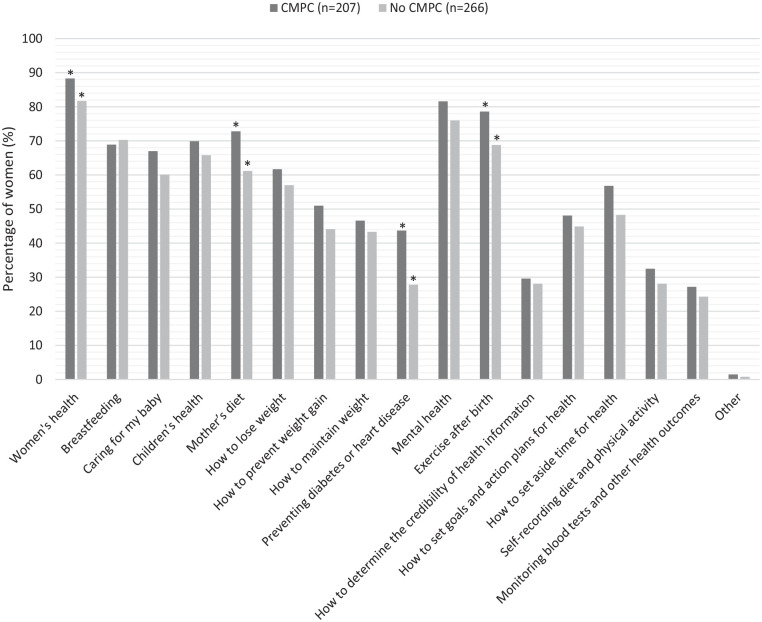

Figure 2 presents the preferred intervention content topics of women. There was a significant difference between women who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication in their choice of the topics; women’s health (87.9% vs 80.8%, p = 0.037), mother’s diet (72.5% vs 60.5%, p = 0.007), preventing diabetes or heart disease (43.5% vs 27.4%, p < 0.001) and exercise after birth (78.3% vs 68.0%, p = 0.014). Of those women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, their five topmost preferences for intervention content were women’s health (87.9%), mental health (81.2%), exercise after birth (78.3%), mother’s diet (72.5%) and their children’s health (69.6%). In comparison, for those who had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, their five topmost preferences for content were women’s health (80.8%), mental health (75.2%), breastfeeding (69.5%), exercise after birth (68.0%) and their children’s health (65.0%).

Figure 2.

Preferred postpartum lifestyle intervention content of women who had or had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication. Data are presented as percentages (%). Data were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test.

CMPC: cardiometabolic pregnancy complication.

*Represents a significant difference between groups.

There was a significant difference between women who experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, women who experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication on intervention content; mother’s diet (78.1% vs 66.7% vs 60.5%, p = 0.006), preventing diabetes or heart disease (51.4% vs 35.3% vs 27.4%, p < 0.001) and exercise after birth (81.9% vs 74.5% vs 68.0%, p = 0.023). A significant post hoc difference was observed between women who had experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication for all three topics (p = 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.007).

Table 2 presents the preferred intervention characteristics of women. There was no difference in preferred intervention provider for women who had or had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, with the top option being someone with expertise in women’s health (e.g. a health professional) for both groups (92.3% vs 89.8%). Both women who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication would like additional content inclusions to primarily be; someone to monitor their progress (69.6% vs 58.6%), which was significantly different (p = 0.014), social support for health (67.1% vs 64.3%), for the intervention setting to be during a maternal child health nurse visit (76.8% vs 74.8%) or online (67.6% vs 67.7%) and to be delivered via online information and resources (76.8% vs 72.2%). Women who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication generally had similar preferences regarding intervention commencement date (7 weeks to 3 months post birth (40.6% vs 41.0%)), session duration (15–30 min (43.0% vs 44.7%)), session frequency (monthly (35.7% vs 37.2%)) and programme duration (1 year (49.3% vs 43.6%)). There was a significant difference between women who had and had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication in their choice of the following intervention frequency; every 3 months (22.7% vs 14.7%, p = 0.024). There was no significant differences between women who had experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication for these intervention characteristics.

Table 2.

Intervention characteristic preferences of women who had or had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication according to the TIDieR checklist.

| Intervention characteristic | Responses | CMPC (n = 207) |

No CMPC (n = 266) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who: preferred programme provider | Someone with expertise in women’s health (e.g. healthcare professional) | 191 (92.3) | 239 (89.8) | 0.364 |

| Someone with expertise in children’s health (e.g. healthcare professional) | 109 (52.7) | 146 (54.9) | 0.629 | |

| Another mother | 63 (30.4) | 64 (24.1) | 0.121 | |

| Someone else | 4 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) | 0.967 | |

| What: additional inclusions | Someone to monitor my progress | 144 (69.6) | 156 (58.6) | 0.014 |

| Send me reminders and prompts | 130 (62.8) | 149 (56.0) | 0.516 | |

| Social support for health | 139 (67.1) | 171 (64.3) | 0.194 | |

| Questions to ask my doctor | 94 (45.4) | 105 (39.5) | 0.194 | |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.1) | 0.447 | |

| When: preferred time to start | 6 weeks or earlier | 63 (30.4) | 88 (33.1) | 0.540 |

| 7 weeks to 3 months | 84 (40.6) | 109 (41.0) | 0.930 | |

| 4–6 months | 42 (20.3) | 50 (18.8) | 0.684 | |

| 7–12 months | 5 (2.4) | 10 (3.8) | 0.408 | |

| After 12 months | 5 (2.4) | 2 (0.8) | 0.137 | |

| Other | 6 (2.9) | 4 (1.5) | 0.296 | |

| Where: preferred setting | Online | 140 (67.6) | 180 (67.7) | 0.993 |

| Maternal child health nurse visit | 159 (76.8) | 199 (74.8) | 0.615 | |

| Mother’s group/playgroup | 108 (52.2) | 146 (54.9) | 0.557 | |

| GP clinic | 117 (56.5) | 127 (47.7) | 0.058 | |

| Other | 4 (1.9) | 3 (1.1) | 0.472 | |

| How: preferred delivery mode | Online information and resource | 159 (76.8) | 192 (72.2) | 0.253 |

| Print information and resource | 76 (36.7) | 96 (36.1) | 0.889 | |

| One-on-one video or phone consultation | 92 (44.4) | 109 (41.0) | 0.449 | |

| One-on-one face-to-face consultation | 115 (55.6) | 146 (54.9) | 0.885 | |

| Group video consultation | 54 (26.1) | 57 (21.4) | 0.236 | |

| Group face-to-face consultation | 83 (40.1) | 97 (36.5) | 0.420 | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.377 | |

| How often: preferred session frequency | Every 6 months | 8 (3.9) | 14 (5.3) | 0.474 |

| Every 3 months | 47 (22.7) | 39 (14.7) | 0.024 | |

| Every month | 74 (35.7) | 99 (37.2) | 0.742 | |

| Every fortnight | 44 (21.3) | 68 (25.6) | 0.274 | |

| Every week | 28 (13.5) | 37 (13.9) | 0.904 | |

| Once off | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 0.715 | |

| Other | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.5) | 0.961 | |

| How long: preferred session duration (min) | <15 | 15 (7.2) | 13 (4.9) | 0.281 |

| 15–30 | 89 (43.0) | 119 (44.7) | 0.705 | |

| 30–45 | 75 (36.2) | 92 (34.6) | 0.710 | |

| 45–60 | 25 (12.1) | 36 (13.5) | 0.639 | |

| >60 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 0.715 | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.277 | |

| How long: preferred programme duration | <1 month | 8 (3.9) | 8 (3.0) | 0.609 |

| 1 month | 16 (7.7) | 29 (10.9) | 0.243 | |

| 3 months | 23 (11.1) | 43 (16.2) | 0.116 | |

| 6 months | 53 (25.6) | 63 (23.7) | 0.630 | |

| 1 year | 102 (49.3) | 116 (43.6) | 0.220 | |

| Other | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.5) | 0.961 |

CMPC: cardiometabolic pregnancy complication.

Data are presented as n (%) and were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test.

Behaviour change needs according to the COM-B system

Capability

There was no difference in reported capability between women with and without cardiometabolic pregnancy complications (Table 3). The three main things women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications suggested they would need to participate in a postpartum lifestyle intervention were to know more about how to do it (e.g. have a better understanding of effective ways to increase exercise; 69.1%), know how to create restful time or space for themselves (65.2%) and have more mental strength (e.g. learn how to resist cravings more; 65.2%). In comparison, women without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications suggested they would similarly have to have more mental strength (62.4%), know how to create restful time or space for themselves (59.4%) and know more about why it was important (e.g. have a better understanding of how foods affect my health; 58.6%). There was a significant difference between women who experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, women who experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication regarding the following capability needs; known how to organize, plan and prioritize (68.6% vs 57.8% vs 54.5%, p = 0.046). A significant post hoc difference was observed between women who had experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication for this capability factor (p = 0.013).

Table 3.

Behaviour change needs of women who have and have not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication according to the COM-B system.

| Behaviour change need | Answer | CMPC (n = 207) |

No CMPC (n = 266) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability: physical and psychological – I would have to. . . | Know more about why it was important (e.g. have a better understanding of how foods affect my health) | 129 (62.3) | 156 (58.6) | 0.418 |

| Know where to find information | 134 (64.7) | 150 (56.4) | 0.066 | |

| Know more about how to do it (e.g. have a better understanding of effective ways to increase exercise) | 143 (69.1) | 154 (57.9) | 0.130 | |

| Know how to create restful time or space for myself | 135 (65.2) | 158 (59.4) | 0.196 | |

| Have better physical skills (e.g. learn how to cook healthy meals for the family) | 89 (43.0) | 116 (43.6) | 0.894 | |

| Know how to organize, plan and prioritize (e.g. exercise during child’s nap time; incorporate into usual routine, such as taking baby for a walk) | 131 (63.3) | 145 (54.5) | 0.055 | |

| Have more physical strength (e.g. having the fitness to exercise) | 131 (63.3) | 148 (55.6) | 0.094 | |

| Have more mental strength (e.g. learn how to resist cravings more) | 135 (65.2) | 166 (62.4) | 0.528 | |

| Overcome physical limitations (e.g. recovery from childbirth, coping with lack of sleep) | 128 (61.8) | 155 (58.3) | 0.433 | |

| Overcome mental obstacles (e.g. managing stress or negative thoughts about self) | 126 (60.9) | 149 (56.0) | 0.288 | |

| Have more physical stamina (e.g. be able to exercise for longer) | 100 (48.3) | 112 (42.1) | 0.178 | |

| Have more mental stamina (e.g. be able to stick to a plan to eat healthy) | 105 (50.7) | 135 (50.8) | 0.995 | |

| Something else | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.5) | 0.604 | |

| Opportunity: physical and social – I would have to. . . | Have more time to do it (e.g. create a specific time during the day to exercise) | 151 (72.9) | 192 (72.2) | 0.853 |

| Have a flexible work arrangement (e.g. part-time employment) | 86 (41.5) | 125 (47.0) | 0.237 | |

| Have enough money to do it (e.g. earn enough to pay for gym membership) | 118 (57.0) | 159 (69.8) | 0.544 | |

| Have the necessary materials (e.g. exercise equipment) | 98 (47.3) | 100 (37.6) | 0.033 | |

| Have it more easily accessible (e.g. online access to the intervention) | 99 (47.8) | 127 (47.7) | 0.986 | |

| Have it incorporated with my baby’s appointment (e.g. maternal and child health visits) | 95 (45.9) | 120 (45.1) | 0.866 | |

| Have a conducive environment to do it (e.g. access to recreational facilities and parks) | 83 (40.1) | 94 (35.3) | 0.289 | |

| Have more people around me doing it (e.g. be part of a ‘crowd’ who are doing it) | 84 (40.6) | 97 (36.5) | 0.361 | |

| Have more triggers to prompt me (e.g. have more reminders to exercise at a specific time) | 91 (44.0) | 84 (31.6) | 0.006 | |

| Have the support of my partner on health issues (e.g. verbal and emotional engagement) | 91 (44.0) | 108 (40.6) | 0.463 | |

| Have practical support from others (e.g. help with childcare and chores from partner, family and friends) | 120 (58.0) | 141 (53.0) | 0.282 | |

| Have someone to hold me accountable | 57 (27.5) | 65 (24.4) | 0.445 | |

| Something else | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) | 0.125 | |

| Motivation: automatic and reflective – I would have to. . . | Feel that I want to do it enough (e.g. enjoy eating healthy or exercising) | 152 (73.4) | 168 (63.2) | 0.018 |

| Feel that I need to do it enough (e.g. believe that my own health is important and feel the need to prioritize self-care) | 136 (65.7) | 157 (59.0) | 0.138 | |

| Believe that it would be a good thing to do (e.g. it will help me cope emotionally or make me feel better) | 132 (65.7) | 153 (57.5) | 0.168 | |

| Believe that it is good for my children (e.g. I am being a good example for my child) | 126 (60.9) | 180 (67.7) | 0.125 | |

| Develop better plans for doing it (e.g. have clearer and better developed plan for eating) | 117 (56.5) | 129 (48.5) | 0.083 | |

| Develop a habit of doing it (e.g. get into a pattern of eating healthy without having to think) | 139 (67.1) | 173 (65.0) | 0.631 | |

| Believe in my ability to do it (e.g. have confidence in my ability to prepare healthy meals) | 115 (55.6) | 126 (47.4) | 0.077 | |

| It would have to fit my cultural and religious beliefs (e.g. beliefs about the type of food to eat when breastfeeding) | 41 (19.8) | 55 (20.7) | 0.815 | |

| Something else | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0.256 |

CMPC: cardiometabolic pregnancy complication.

Data are presented as n (%) and were analysed using a Pearson’s chi-square test.

Opportunity

There was a significance difference between those women with and without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications in choice of the following opportunity factors; have necessary materials (e.g. exercise equipment; 47.3% vs 37.6%, p = 0.033) and have more triggers to prompt me (e.g. have more reminders to exercise at a specific time; 44.0% vs 31.6%, p = 0.006) (Table 3). The three main things women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications suggested they would need to participate in a postpartum lifestyle intervention were to have more time to do it (e.g. create a specific time during the day to exercise; 72.9%), have practical support from others (e.g. help with childcare and chores from partner, family and friends; 58.0%) and have enough money to do it (e.g. earn enough to pay for gym membership; 57.0%). In comparison, women without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications suggested they would also have to have more time to do it (72.2%), have enough money to do it (69.8%) and have practical support from others (53.0%). There was a significant difference between women who experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, women who experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM and women who did not experience a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication regarding the following opportunity-related behaviour change need; have more triggers to prompt me (40.0% vs 48.0% vs 31.6%, p = 0.011). A significant post hoc comparison was observed between women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM and women who had not experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication for this opportunity factor (p = 0.011).

Motivation

There was a significance difference between those women with and without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications for the following motivation factor: feel I want to do it enough (e.g. enjoy eating healthy or exercising; 73.4%, 63.2%, p = 0.018) (Table 3). With respect to motivation, the three upmost things women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications suggested they would need were to feel that they want to do it enough (e.g. enjoy eating healthy or exercising; 73.4%), develop a habit of doing it (e.g. get into a pattern of eating healthy without having to think; 67.1%) and feel that they need to do it enough (e.g. believe that their own health is important and feel the need to prioritize self-care; 65.7%). In comparison, women without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications suggested they would have to believe that it is good for their children (e.g. I am being a good example for my child; 67.7%), develop a habit of doing it (65.0%) and feel that they want to do it enough (63.2%). There were no significant differences between women who had experienced GDM +/− another cardiometabolic pregnancy complication, women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication without GDM and women who had experienced a cardiometabolic pregnancy complication regarding motivation-related behaviour change needs.

Discussion

This is the first study to use a framework-based approach to explore and compare preferred intervention characteristics (based on the TIDieR checklist) and behaviour change needs (based on the COM-B system) of women with or without prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications for engagement in postpartum lifestyle interventions.

We report subtle differences in preferred intervention content between groups. A significantly higher portion of women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications desired intervention content to enhance knowledge including on women’s health, diet, preventing T2D and CVD, exercise and monitoring progress. The preference for content on preventing cardiometabolic disease may be related to these women being aware of their increased future T2D and CVD risk. Alternatively, they may have dissatisfaction with this information received from healthcare professionals. This is consistent with some women with prior GDM and PE reporting feeling abandoned by the healthcare system and unsupported in managing cardiometabolic disease risk, general health and wellbeing postpartum.29 –34 Where lifestyle support is provided, some women report receiving competing information from multiple healthcare professionals and a lack of empathetic and patient-centred and culturally sensitive information.32,35,36 Postpartum lifestyle interventions for these women should therefore include appropriate information, skill development and risk communication specific to T2D and CVD risk awareness and risk reduction.

Both groups preferred intervention content to be on women’s health and mental health with monitoring of progress and social support for their health. A lack of social support from partners, family, friends and healthcare professionals is a commonly reported barrier to engagement in healthy lifestyles postpartum, with its presence a commonly reported facilitator 12 associated with improved physical activity, diet and depressive symptoms. 37 In addition, some women with GDM desire access to peer support groups to aid in postpartum lifestyle management. 38 Regarding mental health, previous studies report a higher portion of women who experienced PE had higher levels of depression 6 months postpartum and were more likely to describe their birth as a traumatic event compared to women who experienced a normotensive pregnancy. 39 GDM was similarly associated with increased postpartum anxiety and depression. 40 While lifestyle interventions typically focus on diet and physical activity, good mental health is an integral part of a healthy lifestyle. Poor mental health is also a barrier to engagement in a healthy diet and physical activity in women with prior GDM. 15 This emphasizes the need to consider a holistic approach to lifestyle interventions incorporating mental health components.

We report the majority of women were interested in postpartum lifestyle programmes and would prefer them to be delivered by someone with expertise in women’s health, such as healthcare professionals. This is consistent with women having regular interactions with healthcare professionals during pregnancy, 41 which likely facilitates building of trust and rapport. Furthermore, postpartum lifestyle interventions delivered by healthcare professionals are more effective for weight loss. 25 Over two-thirds of all women also preferred the setting to be either their maternal and child health nurse visits or online and for content to be delivered online or via one-on-one face-to-face consultations. This coincides with an increased popularity and use of digital and eHealth technologies, 42 which are both highly accepted among postpartum women 43 and effective in facilitating postpartum weight management. 42 In addition, eHealth interventions can provide more flexibility and address some barriers to engagement for postpartum women including time commitments.43,44 With > 85% of postpartum women owning a smartphone with Internet access, 45 engaging high-risk women in postpartum healthy lifestyle interventions will likely benefit from face-to-face consultations aided by technology-based engagement, information and resources.46,47

We report both groups of women would prefer postpartum lifestyle interventions to be initiated between 7 weeks to 3 months postpartum and last ~1 year. There is a lack of consensus regarding optimal initiation and duration of postpartum lifestyle interventions. 41 A recent systematic review of women with previous GDM suggests those initiated within 6 months of birth are more effective in reducing future T2D risk than those commenced later, 48 coinciding with the current participants preferences. However, attrition in lifestyle interventions is higher in the early postpartum period (6-week compared to 6-month postpartum follow-up visit), 17 indicating challenges for early commencement. The majority of women preferred the intervention to be monthly sessions of 15–30 min, consistent with lack of time as a common barrier to engagement in postpartum lifestyle interventions, 12 and the most prevalent opportunity-related behaviour change factor for engagement in this study. Shorter session and programme lengths and less frequent sessions will likely engage, recruit and retain more women than longer programmes with more frequent and longer sessions. Further research should investigate how to achieve desired intervention preferences without compromising intervention effectiveness. Of interest, we note significantly more women with prior cardiometabolic complications preferred lower frequency (3 monthly) appointments. This could indicate the need for a period of adjustment before initiating lifestyle management for some of these high-risk women, potentially related to factors including greater physical and mental health demands of complicated pregnancies.39,40,49

With respect to behaviour change needs, there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding capability-related factors. However, regarding opportunity, significantly more women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications felt they needed to have the necessary materials (e.g. exercise equipment) and more triggers to prompt them (e.g. exercise reminders), and regarding motivation, significantly more women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications felt they had to want to do it enough (e.g. enjoy eating healthy or exercising), to engage in postpartum lifestyle interventions. It is possible these women already have insight into the need to change their behaviours and require more resources and support and something more tailored to their preferences to engage. Previous research using the COM-B in multi-ethnic postpartum GDM women’s engagement in healthful behaviours similarly reported beliefs about consequences and the necessity of health behaviours as a key motivation factor influencing engagement. 15 Additional research identifying barriers to reducing diabetes risk through lifestyle change following GDM reports women acknowledging that being held accountable and having more resources (e.g. free exercise facilities, healthy recipes, home exercise equipment or videos) would help them to be healthier. 36 The lack of differences between the two groups regarding other behaviour change needs suggests barriers to lifestyle engagement faced are similar. Emphasizing facilitators and practically addressing these barriers is crucial in developing a lifestyle intervention in which participants can implement healthful behaviours in an engaged, sustainable, self-sufficient and long-term manner.

The strengths of this study include being the first to compare intervention characteristic preferences and behaviour change needs of women with and without a range of prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications. This extends prior research with women in the general population or those with GDM to explore other cardiometabolic pregnancy complications. Due to the smaller sample size in these groups, it was not possible to perform subgroup analysis for each specific pregnancy complication which is warranted in future research. We report a high prevalence of women born outside of Australia or from a cultural or ethnic background separate to Caucasian. This represents the multicultural society of present-day Australia, 50 increasing the findings transferability and generalizability to the Australian population. However, since the sample is mostly well educated, working women with a middle-to-high income, it does not focus on women where health equity is likely compromised, for example those with low income, low education levels and recent migrants and refugees. Future research should consider further amplifying these women’s voices where possible in addition to better understand how intervention preferences and behaviour change needs may differ depending on cultural background to enhance patient-centred care and the cultural appropriateness of postpartum intervention content and delivery. Such differences have previously been explored in postpartum women in general, with subtle differences observed in preferences of women with Oceanian background compared with Asian background on intervention characteristics including later initiation, less frequent and shorter duration sessions and consideration of the cultural relevance of food and health practices. 51 We were not able to explore these differences further by cardiometabolic pregnancy complication due to the limited sample size in stratified groups and note this as an important area for future research. Future research should also investigate barriers to accessing lifestyle interventions for women and how to address these. We acknowledge the original survey was only tested for acceptability, not reliability and validity. We also acknowledge that no prior sample size calculations were conducted, due to no prior research in this area.

Conclusion

Postpartum women with prior cardiometabolic pregnancy complications are interested in engaging in lifestyle interventions postpartum. They have unique preferences regarding intervention characteristics and behaviour change needs which may influence their engagement. These include the intervention being centred around the topic of women’s health and cardiometabolic health, diet and exercise after birth, providing accountability, assisting women in understanding their risks and the importance of engaging in a healthy lifestyle postpartum and supporting and motivating them to engage within their current responsibilities. Consideration of these is crucial for tailored postpartum lifestyle intervention design and implementation success to overcome barriers and enhance facilitators to engagement. This will improve engagement of these high-risk women in postpartum lifestyle interventions, in the hope of improving their overall health and wellbeing and their risks of future cardiometabolic disease.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455057241247748 for Preferred lifestyle intervention characteristics and behaviour change needs of postpartum women following cardiometabolic pregnancy complications by Elaine K Osei-Safo, Siew Lim, Maureen Makama, Mingling Chen, Helen Skouteris, Frances Taylor, Cheryce L Harrison, Melinda Hutchesson, Christie J Bennett, Helena Teede, Angela Melder and Lisa J Moran in Women’s Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-whe-10.1177_17455057241247748 for Preferred lifestyle intervention characteristics and behaviour change needs of postpartum women following cardiometabolic pregnancy complications by Elaine K Osei-Safo, Siew Lim, Maureen Makama, Mingling Chen, Helen Skouteris, Frances Taylor, Cheryce L Harrison, Melinda Hutchesson, Christie J Bennett, Helena Teede, Angela Melder and Lisa J Moran in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the women who participated in the study.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Elaine K Osei-Safo  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6535-5517

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6535-5517

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The online survey study was approved by the Monash University HREC (Project no. 29273) on 21 September 2021. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Consent for publication: Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Author contribution(s): Elaine K Osei-Safo: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Siew Lim: Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Maureen Makama: Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Mingling Chen: Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Helen Skouteris: Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Frances Taylor: Writing – review & editing.

Cheryce L Harrison: Funding acquisition; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Melinda Hutchesson: Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Christie J Bennett: Writing – review & editing.

Helena Teede: Funding acquisition; Writing – review & editing.

Angela Melder: Writing – review & editing.

Lisa J Moran: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: the research was funded by a Heart Foundation of Australia Vanguard (grant no. 104879) and Strategic Grant (grant no. 105535). L.J.M was funded by a Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (grant no. 101169) and a Veski Fellowship. S.L was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship (grant no. APP 1139481). C.L.H was funded by a NHMRC CRE Health in Preconception and Pregnancy Senior Postdoctoral Fellowship (grant no. 1171142) and H.T was funded by a NHMRC Fellowship (grant no.2009326).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and material: The original survey is included as a supplementary file. The original data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they are potentially identifiable.

References

- 1. Hauspurg A, Ying W, Hubel CA, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and future maternal cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol 2018; 41(2): 239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharma G, Zakaria S, Michos ED, et al. Improving cardiovascular workforce competencies in cardio-obstetrics: current challenges and future directions. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9(12): e015569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, et al. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19(11): 3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minhas AS, Ying W, Ogunwole SM, et al. The association of adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease: current knowledge and future directions. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2020; 22(12): 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ 2002; 325(7356): 157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arnott C, Patel S, Hyett J, et al. Women and cardiovascular disease: pregnancy, the forgotten risk factor. Heart Lung Circ 2020; 29(5): 662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020; 369: m1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu P, Haththotuwa R, Kwok CS, et al. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017; 10(2): e003497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Timpka S, Fraser A, Schyman T, et al. The value of pregnancy complication history for 10-year cardiovascular disease risk prediction in middle-aged women. Eur J Epidemiol 2018; 33(10): 1003–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CA, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021; 143(18): e902–e916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garovic VD, Dechend R, Easterling T, et al. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis, blood pressure goals, and pharmacotherapy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2022; 79(2): e21–e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Makama M, Awoke MA, Skouteris H, et al. Barriers and facilitators to a healthy lifestyle in postpartum women: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies in postpartum women and healthcare providers. Obes Rev 2021; 22(4): e13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carter-Edwards L, Østbye T, Bastian LA, et al. Barriers to adopting a healthy lifestyle: insight from postpartum women. BMC Res Notes 2009; 2: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ryan RA, Lappen H, Bihuniak JD. Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating and physical activity postpartum: a qualitative systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet 2022; 122(3): 602–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neven ACH, Lake AJ, Williams A, et al. Barriers to and enablers of postpartum health behaviours among women from diverse cultural backgrounds with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis applying the Theoretical Domains Framework. Diabet Med 2022; 39(11): e14945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nicklas JM, Zera CA, Seely EW, et al. Identifying postpartum intervention approaches to prevent type 2 diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011; 11: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang S, Magny-Normilus C, McMahon E, et al. Systematic review of lifestyle interventions for gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2022; 51(2): 115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teh K, Quek IP, Tang WE. Postpartum dietary and physical activity-related beliefs and behaviors among women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study from Singapore. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021; 21(1): 612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Montgomery KS, Bushee TD, Phillips JD, et al. Women’s challenges with postpartum weight loss. Matern Child Health J 2011; 15(8): 1176–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fox H, Topp SM, Callander E, et al. A review of the impact of financing mechanisms on maternal health care in Australia. BMC Public Health 2019; 19(1): 1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim S, Hill B, Teede HJ, et al. An evaluation of the impact of lifestyle interventions on body weight in postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2020; 21(4): e12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ammerman AS, Lindquist CH, Lohr KN, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions to modify dietary fat and fruit and vegetable intake: a review of the evidence. Prev Med 2002; 35(1): 25–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; 6(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014; 348: g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lim S, Liang X, Hill B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention characteristics in postpartum weight management using the TIDieR framework: a summary of evidence to inform implementation. Obes Rev 2019; 20(7): 1045–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Makama M, Chen M, Moran LJ, et al. Postpartum women’s preferences for lifestyle intervention after childbirth: a multi-methods study using the TIDieR checklist. Nutrients 2022; 14(20): 4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel. A guide to designing interventions. 1st ed. London: Silverback Publishing, 2014, pp. 1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Mamopoulos A, et al. Diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes mellitus: an overview of national and international guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2021; 76(6): 367–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Muhwava LS, Murphy K, Zarowsky C, et al. Experiences of lifestyle change among women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): a behavioural diagnosis using the COM-B model in a low-income setting. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(11): e0225431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morrison MK, Lowe JM, Collins CE. Australian women’s experiences of living with gestational diabetes. Women Birth 2014; 27(1): 52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burgess A, Feliu K. Women’s knowledge of cardiovascular risk after preeclampsia. Nurs Womens Health 2019; 23(5): 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Collier SA, Mulholland C, Williams J, et al. A qualitative study of perceived barriers to management of diabetes among women with a history of diabetes during pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011; 20(9): 1333–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ingol TT, Kue J, Conrey EJ, et al. Perceived barriers to type 2 diabetes prevention for low-income women with a history of gestational diabetes: a qualitative secondary data analysis. Diabetes Educ 2020; 46(3): 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skurnik G, Roche AT, Stuart JJ, et al. Improving the postpartum care of women with a recent history of preeclampsia: a focus group study. Hypertens Pregnancy 2016; 35(3): 371–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown SD, Grijalva CS, Ferrara A. Leveraging EHRs for patient engagement: perspectives on tailored program outreach. Am J Manag Care 2017; 23(7): e223–e230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dennison RA, Ward RJ, Griffin SJ, et al. Women’s views on lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: a systematic review, qualitative synthesis and recommendations for practice. Diabet Med 2019; 36(6): 702–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Faleschini S, Millar L, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Women’s perceived social support: associations with postpartum weight retention, health behaviors and depressive symptoms. BMC Womens Health 2019; 19(1): 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dennison RA, Griffin SJ, Usher-Smith JA, et al. ‘Post-GDM support would be really good for mothers’: a qualitative interview study exploring how to support a healthy diet and physical activity after gestational diabetes. PLoS ONE 2022; 17(1): e0262852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roberts L, Henry A, Harvey SB, et al. Depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder six months following preeclampsia and normotensive pregnancy: a P4 study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022; 22(1): 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilson CA, Gómez-Gómez I, Parsons J, et al. The mental health of women with gestational diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international cross-sectional survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2022; 31(9): 1232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Makama M, Skouteris H, Moran LJ, et al. Reducing postpartum weight retention: a review of the implementation challenges of postpartum lifestyle interventions. J Clin Med 2021; 10(9): 1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sherifali D, Nerenberg KA, Wilson S, et al. The effectiveness of eHealth technologies on weight management in pregnant and postpartum women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19(10): e8006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lim S, Tan A, Madden S, et al. Health professionals’ and postpartum women’s perspectives on digital health interventions for lifestyle management in the postpartum period: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019; 10: 767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McKinley MC, Allen-Walker V, McGirr C, et al. Weight loss after pregnancy: challenges and opportunities. Nutr Res Rev 2018; 31(2): 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fernandez N, Copenhaver DJ, Vawdrey DK, et al. Smartphone use among postpartum women and implications for personal health record utilization. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2017; 56(4): 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jelsma JGM, van Poppel MNM, Smith BJ, et al. Changing psychosocial determinants of physical activity and diet in women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2018; 34(1): e2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rollo ME, Baldwin JN, Hutchesson M, et al. The feasibility and preliminary efficacy of an eHealth lifestyle program in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Int J Environm Res Public Health 2020; 17(19): 7115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Goveia P, Cañon-Montañez W, Santos DP, et al. Lifestyle intervention for the prevention of diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018; 9: 583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sandsæter HL, Horn J, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Preeclampsia, gestational diabetes and later risk of cardiovascular disease: women’s experiences and motivation for lifestyle changes explored in focus group interviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19(1): 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Cultural diversity of Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics, https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/cultural-diversity-australia (20 September 2022, Accessed 19 May 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen M, Makama M, Skouteris H, et al. Ethnic differences in preferences for lifestyle intervention among women after childbirth: a multi-method study in Australia. Nutrients 2023; 15(2): 472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455057241247748 for Preferred lifestyle intervention characteristics and behaviour change needs of postpartum women following cardiometabolic pregnancy complications by Elaine K Osei-Safo, Siew Lim, Maureen Makama, Mingling Chen, Helen Skouteris, Frances Taylor, Cheryce L Harrison, Melinda Hutchesson, Christie J Bennett, Helena Teede, Angela Melder and Lisa J Moran in Women’s Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-whe-10.1177_17455057241247748 for Preferred lifestyle intervention characteristics and behaviour change needs of postpartum women following cardiometabolic pregnancy complications by Elaine K Osei-Safo, Siew Lim, Maureen Makama, Mingling Chen, Helen Skouteris, Frances Taylor, Cheryce L Harrison, Melinda Hutchesson, Christie J Bennett, Helena Teede, Angela Melder and Lisa J Moran in Women’s Health