Abstract

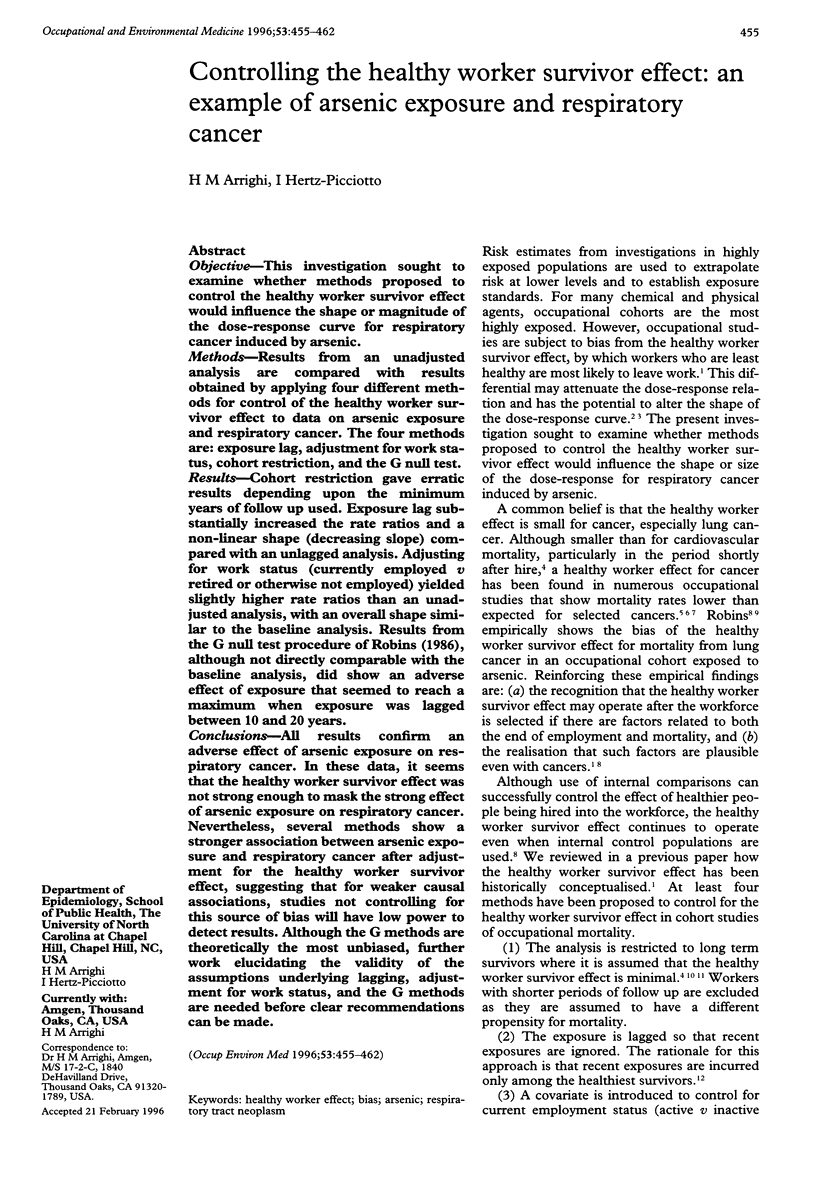

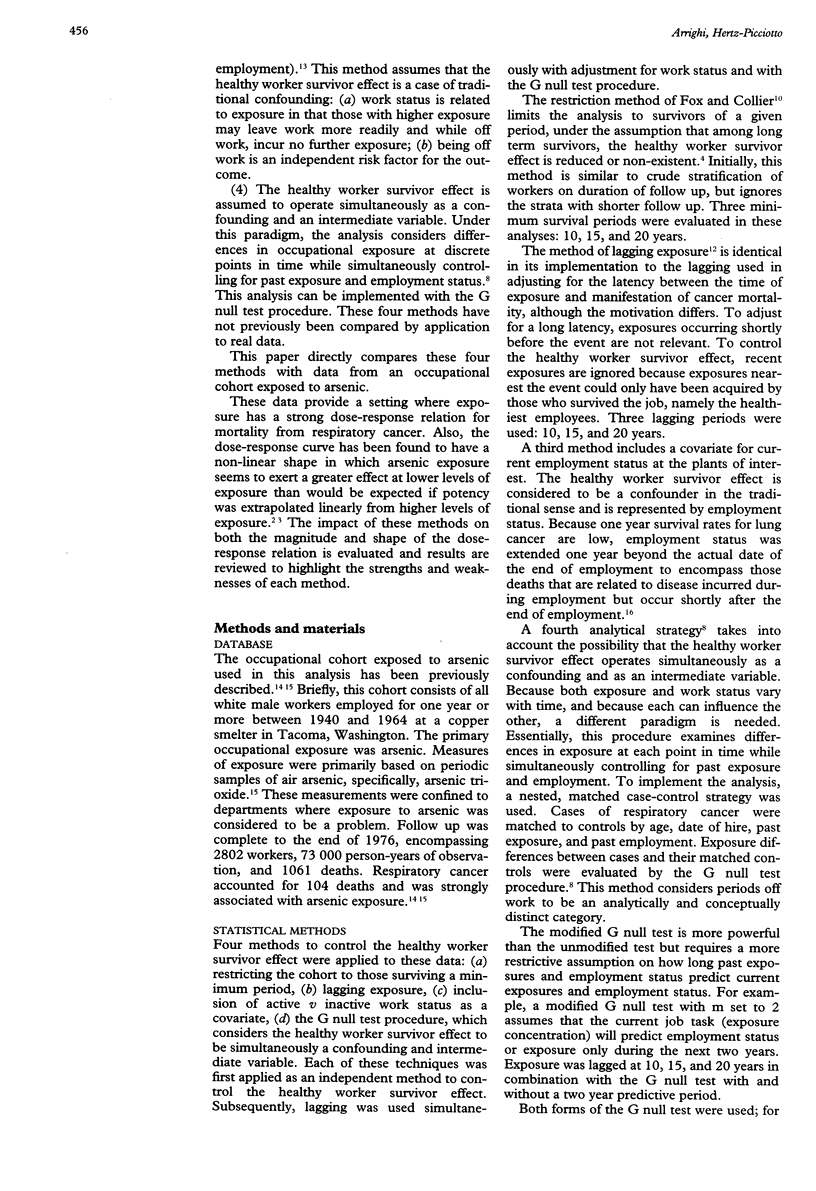

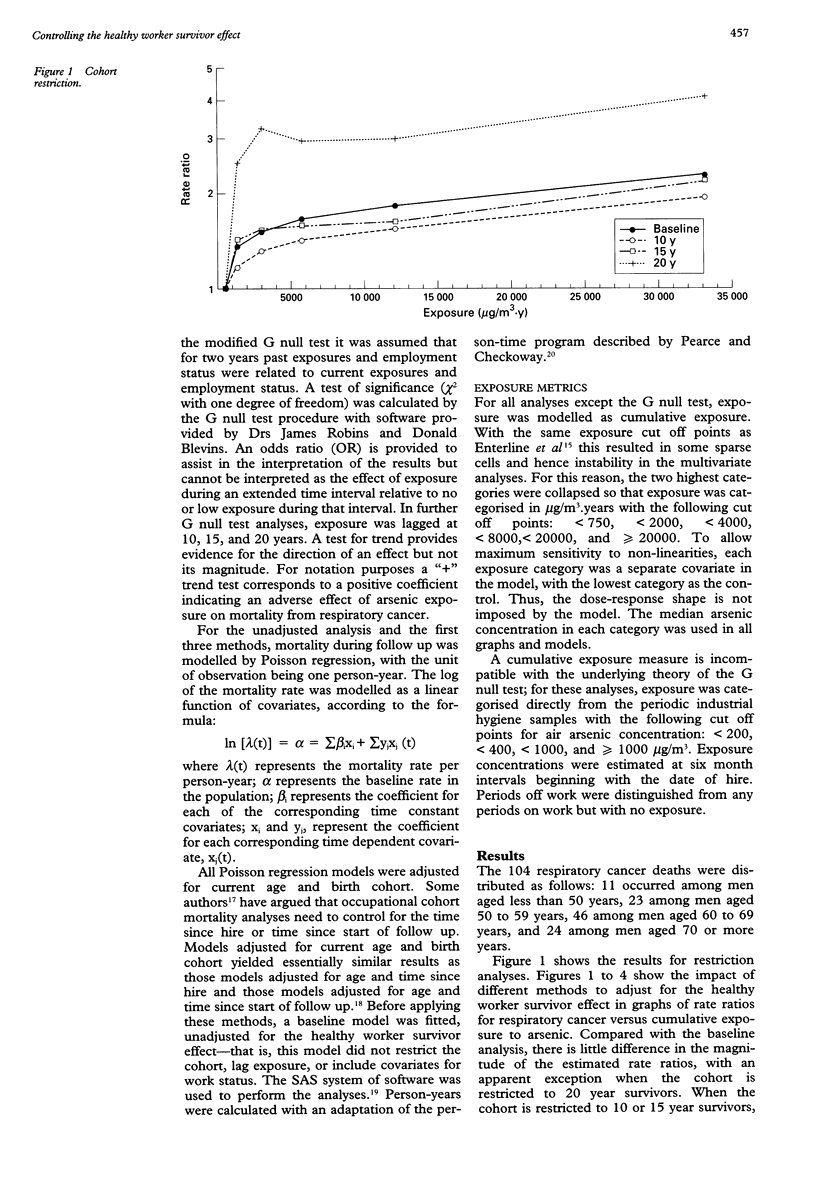

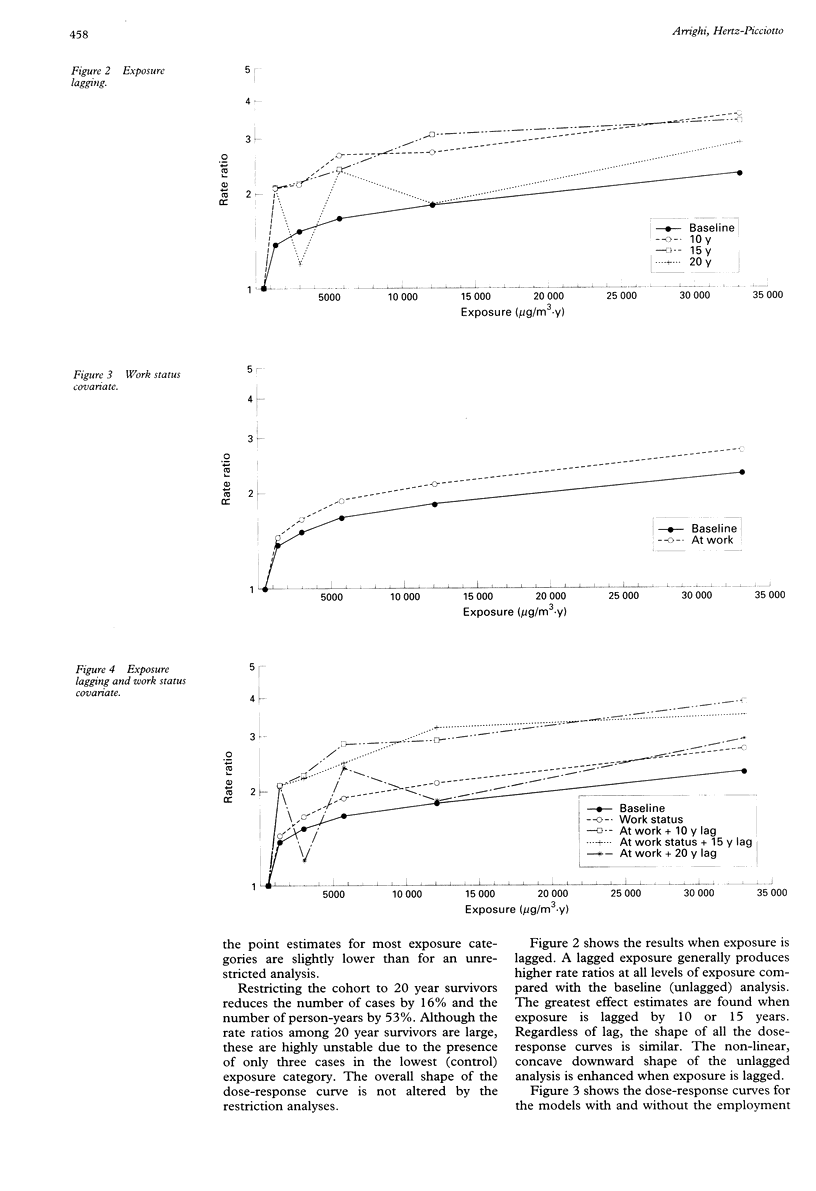

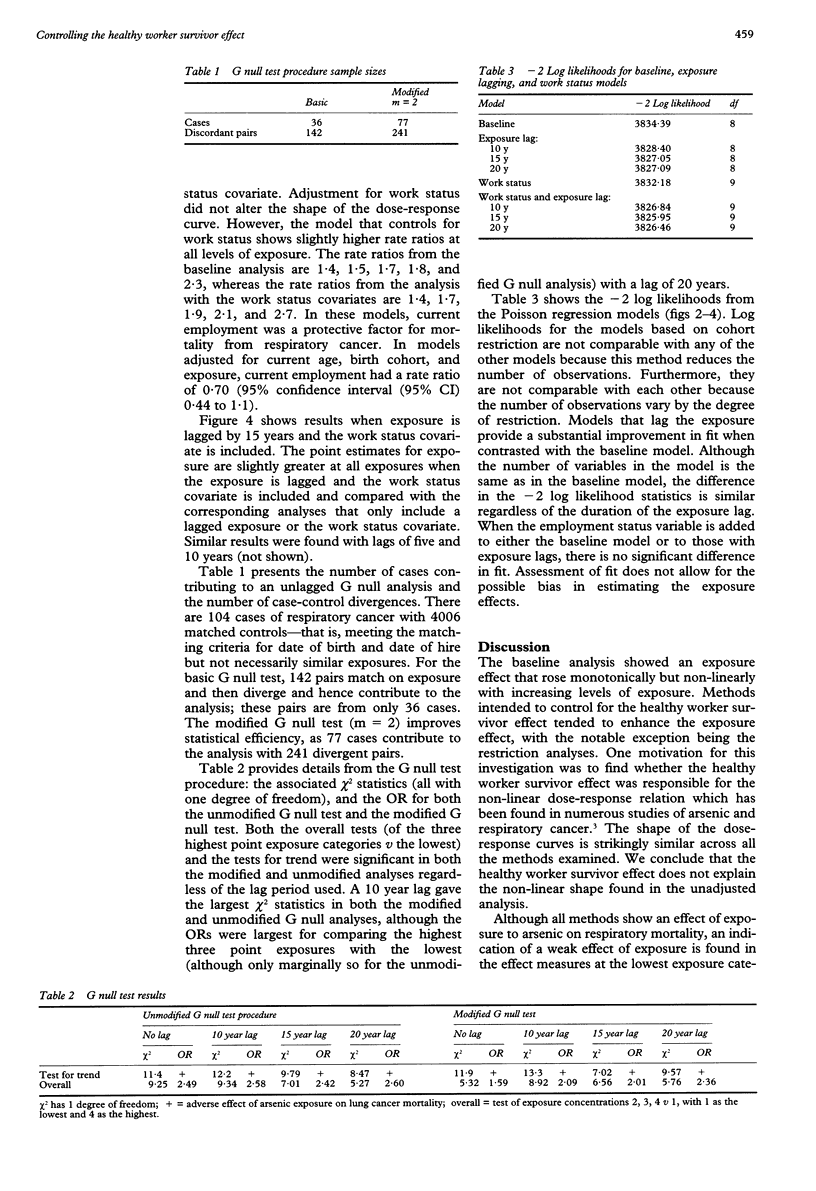

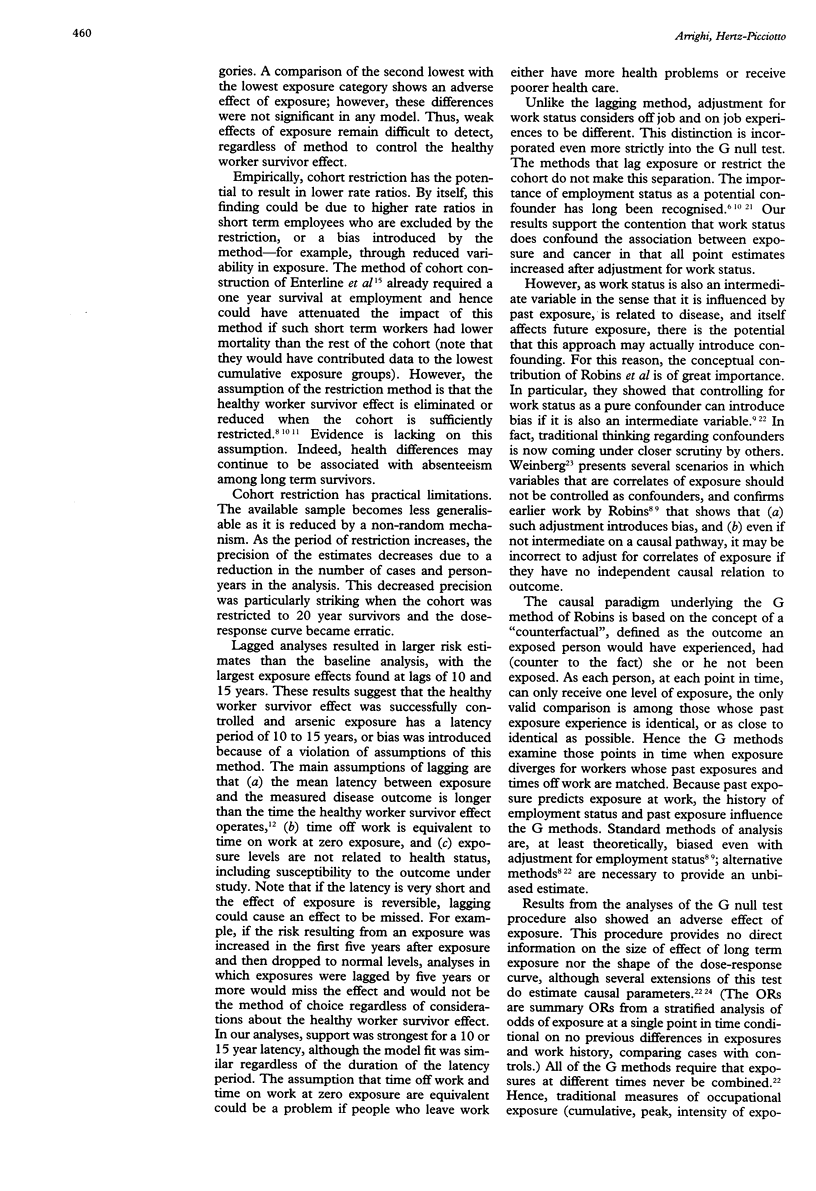

OBJECTIVE--This investigation sought to examine whether methods proposed to control the healthy worker survivor effect would influence the shape or magnitude of the dose-response curve for respiratory cancer induced by arsenic. METHODS--Results from an unadjusted analysis are compared with results obtained by applying four different methods for control of the healthy worker survivor effect to data on arsenic exposure and respiratory cancer. The four methods are: exposure lag, adjustment for work status, cohort restriction, and the G null test. RESULTS--Cohort restriction gave erratic results depending upon the minimum years of follow up used. Exposure lag substantially increased the rate ratios and a non-linear shape (decreasing slope) compared with an unlagged analysis. Adjusting for work status (currently employed upsilon retired or otherwise not employed) yielded slightly higher rate ratios than an unadjusted analysis, with an overall shape similar to the baseline analysis. Results from the G null test procedure of Robins (1986), although not directly comparable with the baseline analysis, did show an adverse effect of exposure that seemed to reach a maximum when exposure was lagged between 10 and 20 years. CONCLUSIONS--All results confirm an adverse effect of arsenic exposure on respiratory cancer. In these data, it seems that the healthy worker survivor effect was not strong enough to mask the strong effect of arsenic exposure on respiratory cancer. Nevertheless, several methods show a stronger association between arsenic exposure and respiratory cancer after adjustment for the healthy worker survivor effect, suggesting that for weaker causal associations, studies not controlling for this source of bias will have low power to detect results. Although the G methods are theoretically the most unbiased, further work elucidating the validity of the assumptions underlying lagging, adjustment for work status, and the G methods are needed before clear recommendations can be made.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arrighi H. M., Hertz-Picciotto I. Controlling for time-since-hire in occupational studies using internal comparisons and cumulative exposure. Epidemiology. 1995 Jul;6(4):415–418. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199507000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi H. M., Hertz-Picciotto I. The evolving concept of the healthy worker survivor effect. Epidemiology. 1994 Mar;5(2):189–196. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair A., Stewart P., O'Berg M., Gaffey W., Walrath J., Ward J., Bales R., Kaplan S., Cubit D. Mortality among industrial workers exposed to formaldehyde. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986 Jun;76(6):1071–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B. C. Definition, sources, magnitude, effect modifiers, and strategies of reduction of the healthy worker effect. J Occup Med. 1992 Oct;34(10):979–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterline P. E., Henderson V. L., Marsh G. M. Exposure to arsenic and respiratory cancer. A reanalysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Jun;125(6):929–938. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterline P. E., Marsh G. M. Cancer among workers exposed to arsenic and other substances in a copper smelter. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Dec;116(6):895–911. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders W. D., Cárdenas V. M., Austin H. Confounding by time since hire in internal comparisons of cumulative exposure in occupational cohort studies. Epidemiology. 1993 Jul;4(4):336–341. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. J., Collier P. F. Low mortality rates in industrial cohort studies due to selection for work and survival in the industry. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976 Dec;30(4):225–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.30.4.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. J., Collier P. F. Mortality experience of workers exposed to vinyl chloride monomer in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride in Great Britain. Br J Ind Med. 1977 Feb;34(1):1–10. doi: 10.1136/oem.34.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert E. S., Marks S. An analysis of the mortality of workers in a nuclear facility. Radiat Res. 1979 Jul;79(1):122–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert E. S. Some confounding factors in the study of mortality and occupational exposures. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Jul;116(1):177–188. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Picciotto I., Holtzman D. A. Issues in conducting a cancer risk assessment using epidemiologic data: arsenic as a case study. Exp Pathol. 1989;37(1-4):219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0232-1513(89)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Picciotto I., Smith A. H. Observations on the dose-response curve for arsenic exposure and lung cancer. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1993 Aug;19(4):217–226. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe G. R. Methodological issues in cohort studies: point estimators of the rate ratio. Int J Epidemiol. 1986 Jun;15(2):257–262. doi: 10.1093/ije/15.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M. G., Holder B. B., Langner R. R. Determinants of mortality in an industrial population. J Occup Med. 1976 Mar;18(3):171–177. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce N., Checkoway H. A simple computer program for generating person-time data in cohort studies involving time-related factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Jun;125(6):1085–1091. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. M., Blevins D., Ritter G., Wulfsohn M. G-estimation of the effect of prophylaxis therapy for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia on the survival of AIDS patients. Epidemiology. 1992 Jul;3(4):319–336. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. A graphical approach to the identification and estimation of causal parameters in mortality studies with sustained exposure periods. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40 (Suppl 2):139S–161S. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9681(87)80018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K., Stayner L. The importance of employment status in occupational cohort mortality studies. Epidemiology. 1991 Nov;2(6):418–423. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing S., Shy C. M., Wood J. L., Wolf S., Cragle D. L., Frome E. L. Mortality among workers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Evidence of radiation effects in follow-up through 1984. JAMA. 1991 Mar 20;265(11):1397–1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]