Abstract

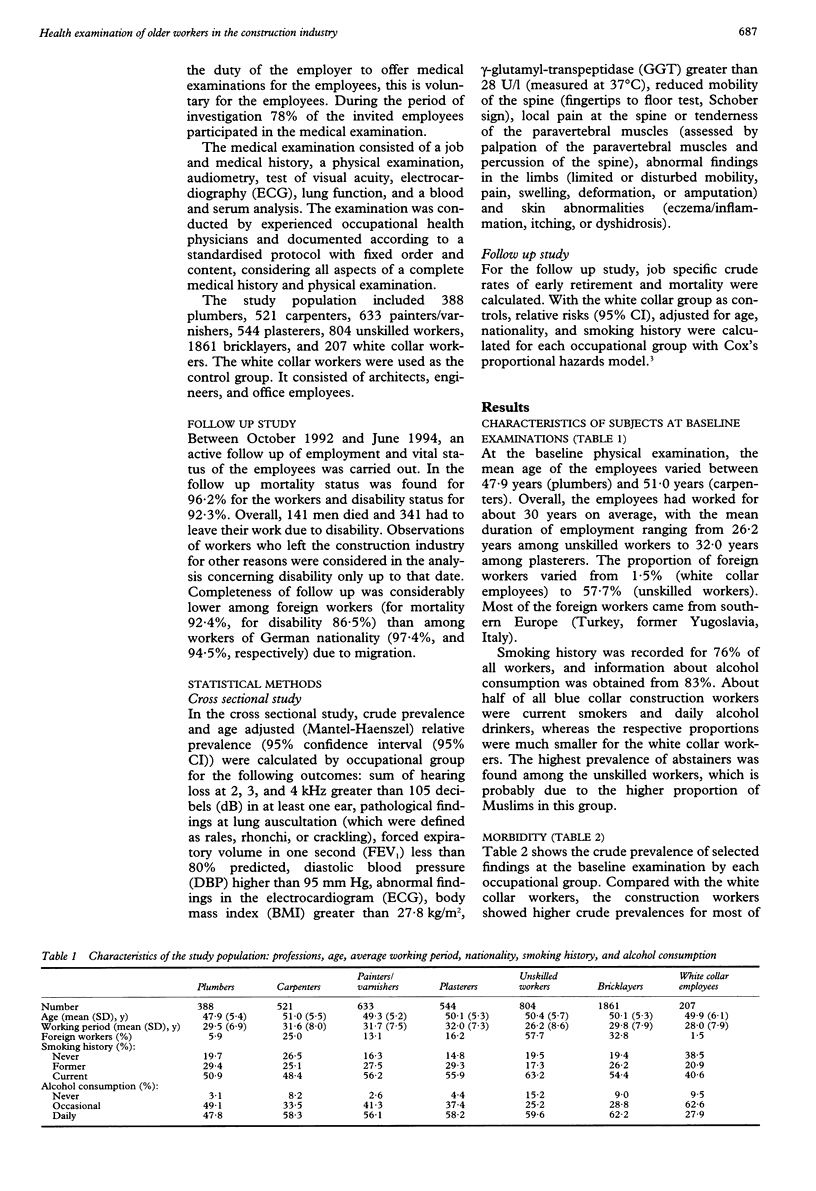

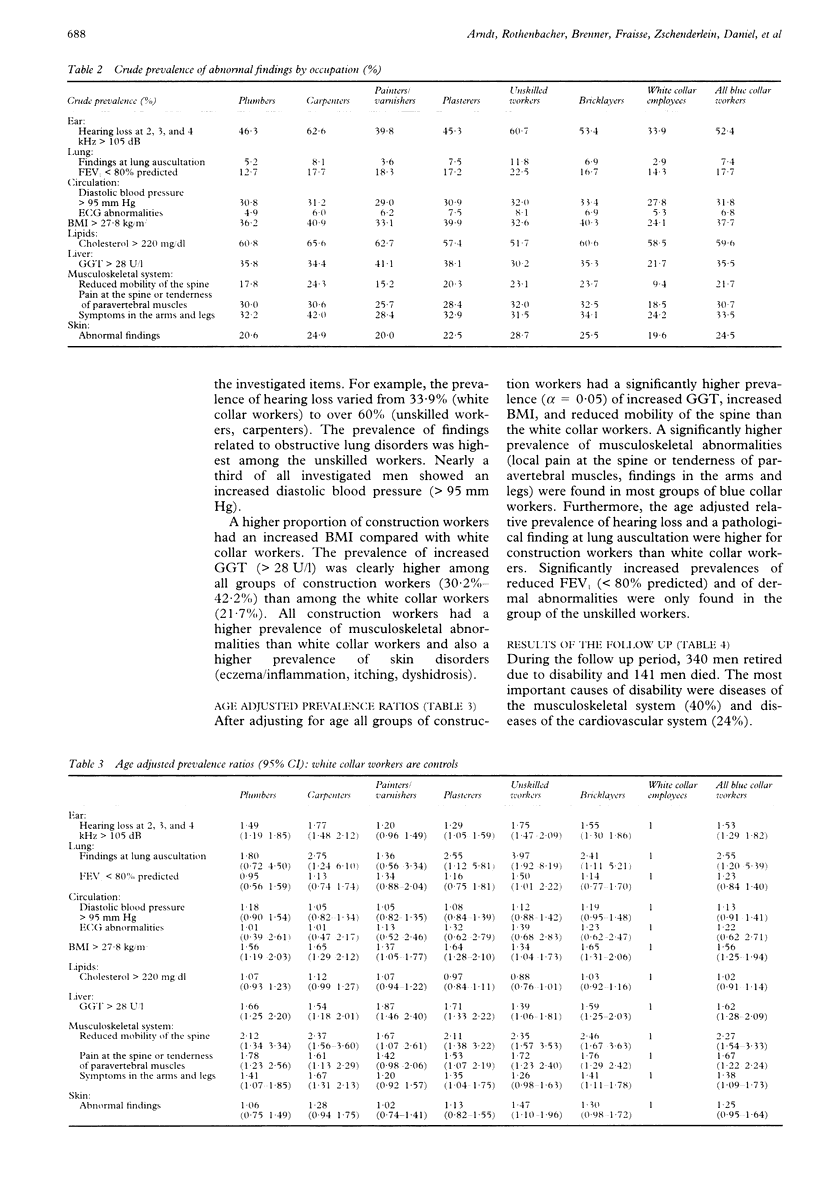

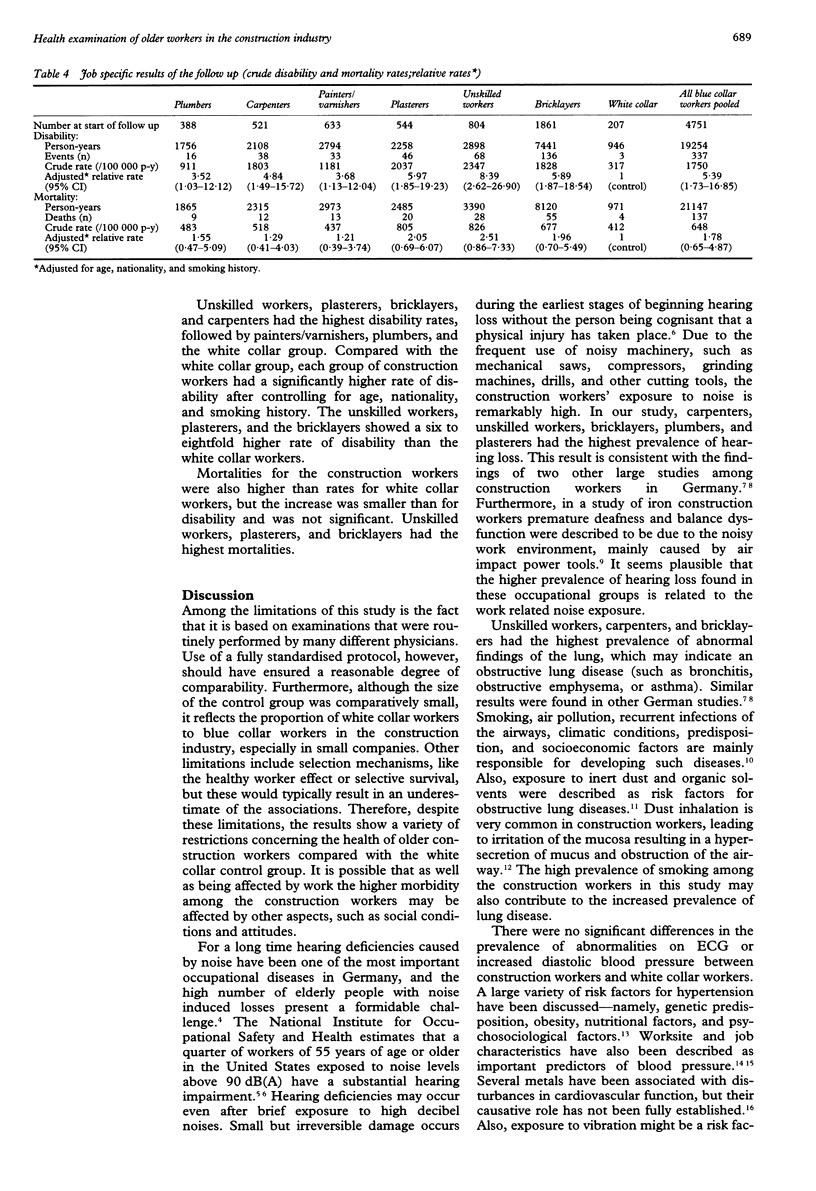

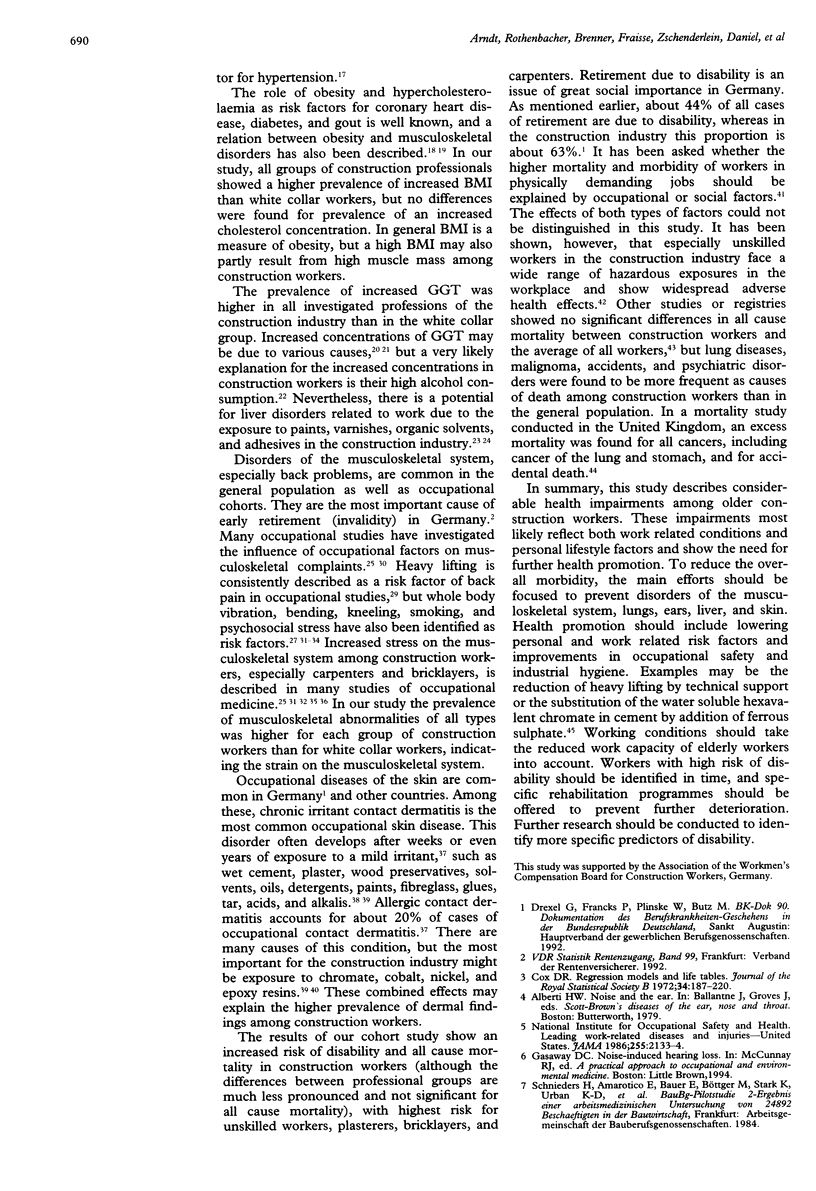

OBJECTIVE: To describe the health status of older construction workers and the occurrence of early retirement due to disability or of mortality within a five year follow up. METHODS: Firstly, a cross sectional study was performed among 4958 employees in the German construction industry, aged 40-64 years, who underwent standardised routine occupational health examinations in 1986-8. The study population included plumbers, carpenters, painters/varnishers, plasterers, unskilled workers, and white collar workers (control group). Job specific prevalence and age adjusted relative prevalence were calculated for hearing loss, abnormal findings at lung auscultation, reduced forced expiratory volume, increased diastolic blood pressure, abnormalities in the electrocardiogram, increased body mass index, hypercholesterolaemia, increased liver enzymes, abnormal findings in an examination of the musculoskeletal system, and abnormalities of the skin. Secondly, follow up for disability and all cause mortality was ascertained between 1992 and 1994 (mean follow up period = 4.5 y). Job specific crude rates were calculated for the occurrence of early retirement due to disability and for all cause mortality. With Cox's proportional hazards model, job specific relative risks, adjusted for age, nationality, and smoking were obtained. RESULTS: Compared with the white collar workers, a higher prevalence of hearing deficiencies, signs of obstructive lung diseases, increased body mass index, and musculoskeletal abnormalities were found among the construction workers at the baseline exam. During the follow up period, 141 men died and 341 men left the labour market due to disability. Compared with white collar workers, the construction workers showed a 3.5 to 8.4-fold increased rate of disability (P < 0.05 for all occupational groups) and a 1.2 to 2.1-fold increased all cause mortality (NS). CONCLUSIONS: This study shows the need and possibilities for further health promotion in workers employed in the construction industry, targeting both work related conditions and personal lifestyle factors. Rehabilitation measures should be enforced to limit the rate of disability among construction workers.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Axelson O. Solvents and the liver. Eur J Clin Invest. 1983 Apr;13(2):109–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1983.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruze M., Gruvberger B., Hradil E. Chromate sensitization and elicitation from cement with iron sulfate. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70(2):160–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart G., Schulte P. A., Robinson C., Sieber W. K., Vossenas P., Ringen K. Job tasks, potential exposures, and health risks of laborers employed in the construction industry. Am J Ind Med. 1993 Oct;24(4):413–425. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700240407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Yeung M., Malo J. L. Occupational asthma. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 13;333(2):107–112. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507133330207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. D., Wang J. D., Jang J. P., Chen Y. Y. Exposure to mixtures of solvents among paint workers and biochemical alterations of liver function. Br J Ind Med. 1991 Oct;48(10):696–701. doi: 10.1136/oem.48.10.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenraads P. J., Nater J. P. Sickness and absence from work due to skin diseases in the construction industry. Review of the literature. Derm Beruf Umwelt. 1984;32(1):17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Vaughan P., Sullivan K., Fletcher T. Mortality study of construction workers in the UK. Int J Epidemiol. 1995 Aug;24(4):750–757. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Døssing M., Arlien-Søborg P., Milling Petersen L., Ranek L. Liver damage associated with occupational exposure to organic solvents in house painters. Eur J Clin Invest. 1983 Apr;13(2):151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1983.tb00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E. Smoking and back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Sep;50(9):658–658. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.9.658-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogari R., Zoppi A., Vanasia A., Marasi G., Villa G. Occupational noise exposure and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1994 Apr;12(4):475–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frymoyer J. W., Pope M. H., Costanza M. C., Rosen J. C., Goggin J. E., Wilder D. G. Epidemiologic studies of low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1980 Sep-Oct;5(5):419–423. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heliövaara M., Mäkelä M., Knekt P., Impivaara O., Aromaa A. Determinants of sciatica and low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991 Jun;16(6):608–614. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmström E. B., Lindell J., Moritz U. Low back and neck/shoulder pain in construction workers: occupational workload and psychosocial risk factors. Part 1: Relationship to low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992 Jun;17(6):663–671. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmström E. B., Lindell J., Moritz U. Low back and neck/shoulder pain in construction workers: occupational workload and psychosocial risk factors. Part 2: Relationship to neck and shoulder pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992 Jun;17(6):672–677. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulshof C., van Zanten B. V. Whole-body vibration and low-back pain. A review of epidemiologic studies. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1987;59(3):205–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00377733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idzior-Waluś B. Coronary risk factors in men occupationally exposed to vibration and noise. Eur Heart J. 1987 Oct;8(10):1040–1046. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B. Some lessons in cardiovascular epidemiology from Framingham. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Feb;37(2):269–282. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieć-Swierczyńska M. Occupational dermatoses and allergy to metals in Polish construction workers manufacturing prefabricated building units. Contact Dermatitis. 1990 Jul;23(1):27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilburn K. H., Warshaw R. H., Hanscom B. Are hearing loss and balance dysfunction linked in construction iron workers? Br J Ind Med. 1992 Feb;49(2):138–141. doi: 10.1136/oem.49.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd M. H., Gauld S., Soutar C. A. Epidemiologic study of back pain in miners and office workers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1986 Mar;11(2):136–140. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell W., Eaton W. W., Anthony J. C., Garrison R. Alcoholism and occupations: a review and analysis of 104 occupations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992 Aug;16(4):734–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riihimäki H., Wickström G., Hänninen K., Luopajärvi T. Predictors of sciatic pain among concrete reinforcement workers and house painters--a five-year follow-up. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1989 Dec;15(6):415–423. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlussel Y. R., Schnall P. L., Zimbler M., Warren K., Pickering T. G. The effect of work environments on blood pressure: evidence from seven New York organizations. J Hypertens. 1990 Jul;8(7):679–685. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarfors E. T., Lithell H. O., Selinus I. Risk factors for the development of hypertension: a 10-year longitudinal study in middle-aged men. J Hypertens. 1991 Mar;9(3):217–223. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stender M., Hense H. W., Döring A., Keil U. Physical activity at work and cardiovascular disease risk: results from the MONICA Augsburg study. Int J Epidemiol. 1993 Aug;22(4):644–650. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson H. O., Andersson G. B. The relationship of low-back pain, work history, work environment, and stress. A retrospective cross-sectional study of 38- to 64-year-old women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989 May;14(5):517–522. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingård E., Alfredsson L., Goldie I., Hogstedt C. Occupation and osteoarthrosis of the hip and knee: a register-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 1991 Dec;20(4):1025–1031. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgaard R. H., Jensen C., Hansen K. Individual and work-related risk factors associated with symptoms of musculoskeletal complaints. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1993;64(6):405–413. doi: 10.1007/BF00517946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]