Abstract

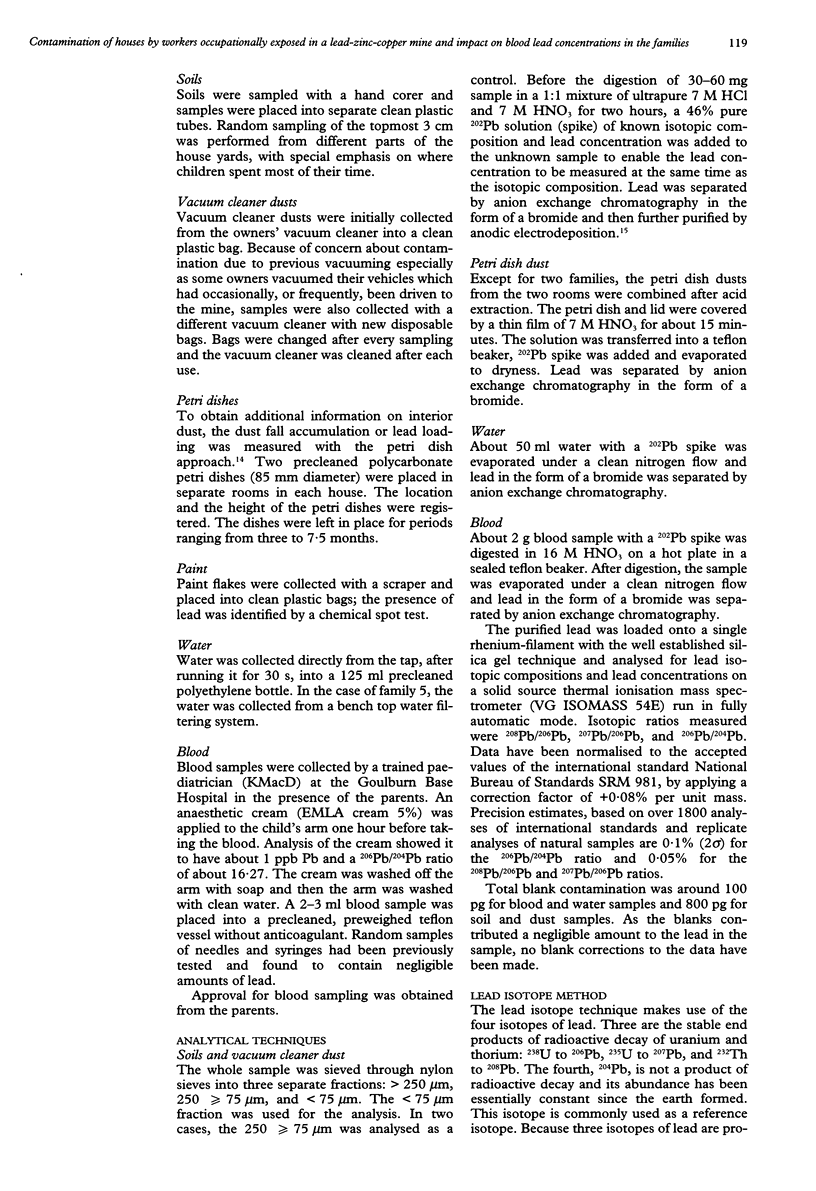

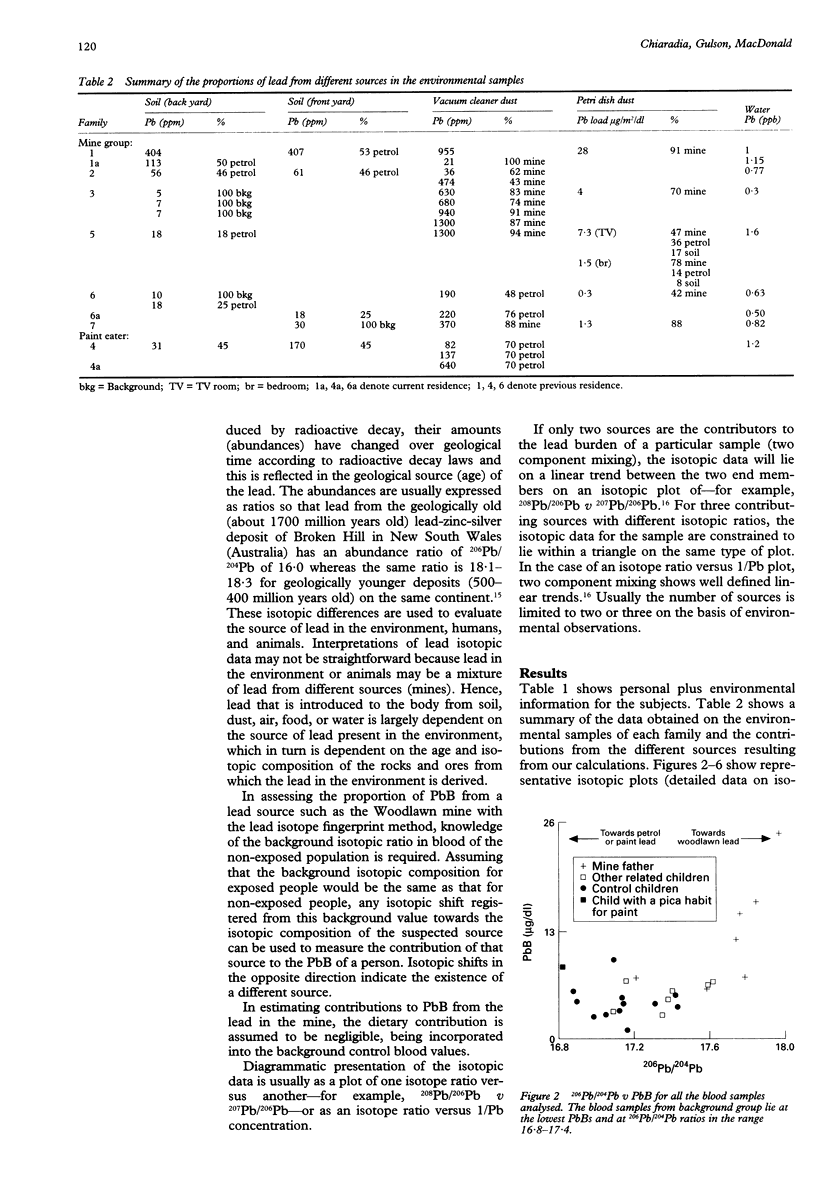

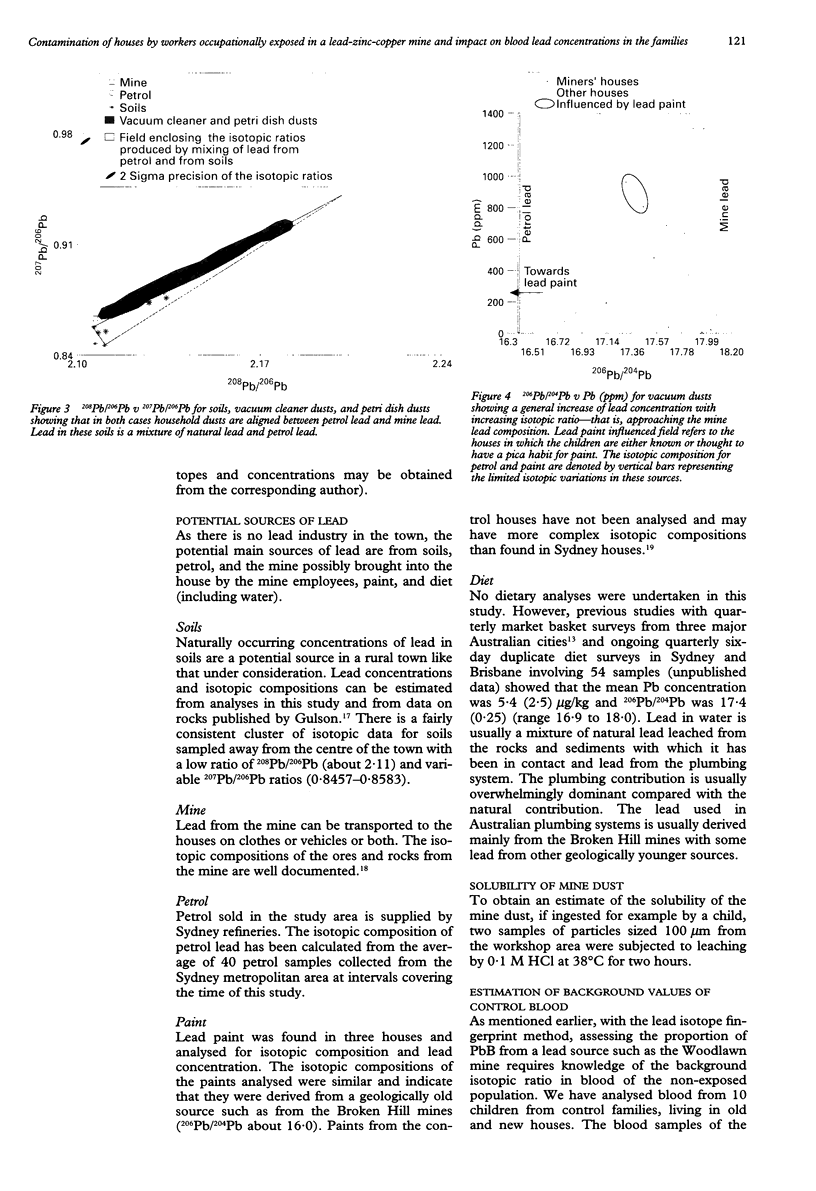

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the pathway of leaded dust from a lead-zinc-copper mine to houses of employees, and the impact on blood lead concentrations (PbB) of children. METHODS: High precision lead isotope and lead concentration data were obtained on venous blood and environmental samples (vacuum cleaner dust, interior dustfall accumulation, water, paint) for eight children of six employees (and the employees) from a lead-zinc-copper mine. These data were compared with results for 11 children from occupationally unexposed control families living in the same city. RESULTS: The median (range) concentrations of lead in vacuum cleaner dust was 470 (21-1300) ppm. In the houses of the mine employees, vacuum cleaner dust contained varying higher proportions of mine lead than did airborne particulate matter measured as dustfall accumulated over a three month period. The median (range) concentrations of lead in soil were 30 (5-407) ppm and these showed no evidence of any mine lead. Lead in blood of the mine employees varied from 7 to 25 micrograms/dl and was generally dominated by mine lead (> 60%). The mean (SD) PbB in the children of the mine employees was 5.7 (1.7) micrograms/dl compared with 4.1 (1.4) micrograms/dl for the control children (P = 0.02). The PbB of all children was always < 10 micrograms/dl, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council goal for all Australians. Some of the control children had higher PbB than the children of mine employees, probably from exposure to leaded paint as six of the eight houses of the control children were > 50 years old. In five of the eight children of mine employees > 20% of PbB was from the lead mine. However, in the other three cases of children of mine employees, their PbB was from sources other than mine lead (paint, petrol, background sources). CONCLUSIONS: Houses of employees from a lead mine can be contaminated by mine lead even if they are not situated in the same place as the mine. Delineation of the mine to house pathway indicates that lead is probably transported into the houses on the clothes, shoes, hair, skin, and in some cases, motor vehicles of the workers. In one case, dust shaken from clothes of a mine employee contained 3000 ppm lead which was 100% mine lead. The variable contamination of the houses was not expected given the precautions taken by mine employees to minimise transportation of lead into their houses. Although five out of the eight children of mine employees had > 20% mine lead in their blood, in no case did the PbB of a child exceed the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council goal of 10 micrograms/dl. In fact, some children in the control families had higher PbB than children of mine employees. In two cases, this was attributed to a pica habit for paint. The PbB in the children of mine employees and controls was independent of the source of lead. The low PbB in the children of mine employees may reflect the relatively low solubility (bioavailability) of the mine dust in 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (< 40 %), behaviour--for example, limited mouthing activity--or diet.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker E. L., Folland D. S., Taylor T. A., Frank M., Peterson W., Lovejoy G., Cox D., Housworth J., Landrigan P. J. Lead poisoning in children of lead workers: home contamination with industrial dust. N Engl J Med. 1977 Feb 3;296(5):260–261. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197702032960507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcourt J. L., Hamrick H. J., O'Tuama L. A., Wooten J., Barker E. L., Jr Increased lead burden in children of battery workers: asymptomatic exposure resulting from contaminated work clothing. Pediatrics. 1978 Oct;62(4):563–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbein A., Wallace J., Sassa S., Kappas A., Butts G., Rohl A., Kaul B. Lead poisoning from art restoration and pottery work: unusual exposure source and household risk. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1992 Jan-Feb;11(1):7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittleman J. L., Engelgau M. M., Shaw J., Wille K. K., Seligman P. J. Lead poisoning among battery reclamation workers in Alabama. J Occup Med. 1994 May;36(5):526–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P., Bach E. Indirect exposures: the significance of bystanders at work and at home. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1986 Dec;47(12):819–824. doi: 10.1080/15298668691390719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulson B. L., Davis J. J., Bawden-Smith J. Paint as a source of recontamination of houses in urban environments and its role in maintaining elevated blood leads in children. Sci Total Environ. 1995 Mar 30;164(3):221–235. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04512-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulson B. L., Davis J. J., Mizon K. J., Korsch M. J., Law A. J., Howarth D. Lead bioavailability in the environment of children: blood lead levels in children can be elevated in a mining community. Arch Environ Health. 1994 Sep-Oct;49(5):326–331. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9954982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulson B. L., Mizon K. J., Korsch M. J., Howarth D., Phillips A., Hall J. Impact on blood lead in children and adults following relocation from their source of exposure and contribution of skeletal tissue to blood lead. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1996 Apr;56(4):543–550. doi: 10.1007/s001289900078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri Y., Toriumi H., Kawai M. Lead exposure among 3-year-old children and their mothers living in a pottery-producing area. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1983;52(3):223–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00526521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M., Toriumi H., Katagiri Y., Maruyama Y. Home lead-work as a potential source of lead exposure for children. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1983;53(1):37–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00406175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye W. E., Novotny T. E., Tucker M. New ceramics-related industry implicated in elevated blood lead levels in children. Arch Environ Health. 1987 May-Jun;42(3):161–164. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1987.9935815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knishkowy B., Baker E. L. Transmission of occupational disease to family contacts. Am J Ind Med. 1986;9(6):543–550. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700090606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira M., Bawden-Smith J., Causer J., Alperstein G., Karr M., Snitch P., Waller G., Fett M. J. Blood lead concentrations of preschool children in central and southern Sydney. Med J Aust. 1996 Apr 1;164(7):399–402. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini R., Candela S., Messori M., Viappiani F. Blood and hair lead levels in 6-year old children according to their parents' occupation. G Ital Med Lav. 1986 Mar;8(2):65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]