Abstract

Brassicaceae represents an important plant family from both a scientific and economic perspective. However, genomic features related to the early diversification of this family have not been fully characterized, especially upon the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, which was followed by increasing aridity in the Asian interior, intensifying monsoons in Eastern Asia, and significantly fluctuating daily temperatures. Here, we reveal the genomic architecture that accompanied early Brassicaceae diversification by analyzing two high-quality chromosome-level genomes for Meniocus linifolius (Arabodae; clade D) and Tetracme quadricornis (Hesperodae; clade E), together with genomes representing all major Brassicaceae clades and the basal Aethionemeae. We reconstructed an ancestral core Brassicaceae karyotype (CBK) containing 9 pseudochromosomes with 65 conserved syntenic genomic blocks and identified 9702 conserved genes in Brassicaceae. We detected pervasive conflicting phylogenomic signals accompanied by widespread ancient hybridization events, which correlate well with the early divergence of core Brassicaceae. We identified a successive Brassicaceae-specific expansion of the class I TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 1 (TPS1) gene family, which encodes enzymes with essential regulatory roles in flowering time and embryo development. The TPS1s were mainly randomly amplified, followed by expression divergence. Our results provide fresh insights into historical genomic features coupled with Brassicaceae evolution and offer a potential model for broad-scale studies of adaptive radiation under an ever-changing environment.

Key words: Cruciferae, genomic features, ancient hybridization, core Brassicaceae karyotype, CBK, TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 1 genes, TPS1s

Brassicaceae contains many model plants and vegetable crops. This study reports two high-quality genomes representing Arabodae (Meniocus linifolius) and Hesperodae (Tetracme quadricornis) and the reconstruction of the ancestral core Brassicaceae karyotype (CBK). The results provide fresh insights into historical genomic features related to Brassicaceae evolution and offer a potential model for broad-scale studies of adaptive radiation under an ever-changing environment.

Introduction

Understanding the molecular and genetic mechanisms that underlie species radiations remains an important, albeit challenging, topic in evolutionary biology. Radiation can result from increased speciation, decreased extinction rates, or both (Naciri and Linder, 2020). This phenomenon is prevalent in nature, with numerous examples, such as butterflies (Edelman et al., 2019), Malawi cichlids (Malinsky et al., 2018), lizards (Garcia-Porta et al., 2019), Darwin’s giant daisies (Fernandez-Mazuecos et al., 2020), and rhododendrons (Ma et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022). However, rapid radiations make phylogenetic reconstruction challenging owing to the limited accumulation of substitutions within a short time. In addition, large population sizes and close evolutionary relationships can result in incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) and hybridization, leading to conflicting gene and species trees (Cai et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2023).

Brassicaceae (Cruciferae) contains approximately 4140 species, many of which are important crops (e.g., cabbage, rapeseed, mustard, and broccoli, among others) and/or model plants in Arabidopsis, Capsella, Brassica, and Arabis (German et al., 2023). Except for the basal Aethionemeae, core Brassicaceae comprises approximately 98.6% of species in five supertribes/clades, i.e., Camelinodae/A, Brassicodae/B, Hesperodae/E, Arabodae/D, and Heliophilodae/C, whose phylogenetic relationships lack resolution because of the likelihood of an early rapid radiation, as implied by many studies (Al-Shehbaz et al., 2006; Bailey et al., 2006; Beilstein et al., 2006, 2008; German et al., 2009; Couvreur et al., 2010; Warwick et al., 2010; Franzke et al., 2011; Hohmann et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2017; Nikolov et al., 2019; Walden et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2020, 2024; Hendriks et al., 2023). In addition, a whole-genome duplication (WGD) event (i.e., At-α WGD) appears to have been essential for novel traits and species diversification in Brassicaceae (Franzke et al., 2011; Edger et al., 2018). This pattern has been observed in several other large and economically important families, including Poaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Solanaceae, and has inspired the development of the WGD radiation lag-time model (Schranz et al., 2012). Indeed, WGD or polyploidization followed by rediploidization has been a major driving force in plant diversification (Soltis et al., 2015; Qiao et al., 2019). Hybridization, which is thought to be the first and most important step toward allopolyploidy, also contributes to species radiation by increasing allelic diversity, thus enhancing adaptability to new and challenging environments (Guo et al., 2021; Slovak et al., 2023).

Recent research suggests that Brassicaceae originated during the middle to late Eocene (40.5–36.9 million years ago [mya]), a period in Earth’s history known as the “icehouse era”. The crown age of Brassicaceae, marked by the divergence of the basal Aethionemeae and core Brassicaceae, is estimated to be between 23.1 and 25.7 mya (Hendriks et al., 2023). This period corresponds to the transition from the Oligocene to the Miocene and the rapid uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, which was followed by increasing aridity in the Asian interior, intensifying monsoons in Eastern Asia, and markedly fluctuating daily temperatures (Zachos et al., 2001; Kagale et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2022). However, molecular and genomic features related to this early diversification remain poorly characterized.

Inferring ancestral genomes is one of the central aspects of comparative genomic analyses (Murat et al., 2017; Anselmetti et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2022). The ancestral crucifer karyotype (ACK) for Brassicaceae has been proposed to feature 8 pseudochromosomes with 22 conserved ancestral genomic blocks (GBs) (Schranz et al., 2006; Lysak et al., 2016). The ACK has been widely used to study the phylogenomic and karyotypic evolutionary patterns of Brassicaceae (Mandakova and Lysak, 2008; Willing et al., 2015; Geiser et al., 2016; Mandakova et al., 2017, 2018, 2020; Walden et al., 2020a; Bayat et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2021). However, the ACK was essentially based on genome sequences and genetic maps of A. thaliana, A. lyrata, C. rubella, and B. rapa (Schranz et al., 2006; Lysak et al., 2016). Later efforts that incorporated the Thellungiella parvula genome did not markedly alter the ACK (Murat et al., 2015). More recently, inclusion of additional genomes from earlier-diverging lineages resulted in the reconstruction of a new haploid ancestral genome (n = 9) for core Brassicaceae (Walden and Schranz, 2023). However, this new karyotype contains only 3392 strictly conserved syntenic genes, likely owing to use of the non-chromosome-level Euclidium syriacum genome to represent Hesperodae/clade E. With the generation of more high-quality chromosome-level genomes and better phylogenomic coverage, an improved ancestral karyotype may provide a better understanding of the Brassicaceae genome and chromosomal evolution.

Species radiation is often accompanied by adaptation to a fluctuating or otherwise challenging environment, in which the timing of the vegetative to reproductive growth transition (i.e., flowering time) plays a pivotal role (Alonso-Blanco et al., 2009; Franzke et al., 2011). Flowering time is tightly regulated by a highly wired gene-regulatory network that links endogenous developmental signals and exogenous environmental signals such as light, temperature, and water availability (Andres and Coupland, 2012; Hyun et al., 2017; Gaudinier and Blackman, 2020). As a signal of sugar or energy availability, the level of trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P), which is synthesized mainly by T6P synthase 1 (TPS1) and T6P phosphatase, determines flowering time, embryogenesis, and other developmental processes, as well as various stress responses (Iordachescu and Imai, 2008; Fernandez et al., 2010; Fichtner et al., 2021; Fichtner and Lunn, 2021). The TPS1-mediated T6P pathway is highly conserved even in prokaryotes; however, the evolutionary patterns of TPS1 gene expansion and/or contraction have not been fully characterized in plants, including Brassicaceae.

Here, we systematically explore the genomic features associated with the early Brassicaceae radiation by analyzing a set of high-quality chromosome-level genomes, including two newly assembled genomes, from species representing each supertribe and the basal Aethionemeae (Huang et al., 2016; German et al., 2023; Hendriks et al., 2023). We propose an ancestral core Brassicaceae karyotype (CBK) that includes 9 pseudochromosomes and 65 conserved GBs. We detect strong phylogenomic conflicts associated with ancient hybridization and identify a highly dynamic pattern of Brassicaceae-specific expansion of class I TPS1 genes. Notably, the expression of these genes responds differentially to fluctuating temperature. Our efforts provide new genomic resources and improve our understanding of Brassicaceae diversification during historical environmental changes.

Results

High-quality chromosome-level reference genomes for Arabodae and Hesperodae

We reconstructed high-quality chromosome-level genome assemblies for two species, Meniocus linifolius (Mli), representing Arabodae/clade D, and Tetracme quadricornis (Tqu), representing Hesperodae/clade E (Figure 1A). A combination of flow cytometry and genomic surveys using ∼50× Illumina short reads revealed that genome sizes were between 246 and 288 Mb for Mli and 721 and 768 Mb for Tqu (supplemental Figures 1 and 2; supplemental Table 1). Cytological analysis indicated that the chromosome number for Mli was 2n = 14 (supplemental Figure 3), although both 2n = 16 and 2n = 14 have been reported for this species (Spaniel et al., 2015). Both species exhibited a low level of heterozygosity with 0.0586% for Mli and 0.0344% for Tqu (supplemental Figure 2). Both genomes were sequenced and assembled using PacBio HiFi long reads and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) sequencing (supplemental Figure 4; supplemental Tables 2 and 3). The final nuclear genome assemblies for Mli and Tqu were approximately 244.24 and 724.93 Mb in length, with contig N50s of approximately 15.43 and 45.06 Mb and maximum scaffold lengths of 40.91 and 133.35 Mb, respectively (supplemental Table 4). Both species have seven pseudochromosomes, to which more than 93% (Mli) and 99% (Tqu) of the contigs were anchored via Hi-C data (supplemental Figures 5 and 6; supplemental Table 5). Both assemblies exhibited high completeness, with >98.5% of the eudicot Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCOs) identified (supplemental Figure 7; supplemental Table 6) (Simao et al., 2015). In addition, >99% of the Illumina short reads were properly mapped to the genome assemblies (supplemental Table 7). The long terminal repeat (LTR) assembly index was 11.07 for Mli and 23.46 for Tqu, meeting the “Reference” and “Gold” standards, respectively (supplemental Figure 8; supplemental Table 4) (Ou et al., 2018).

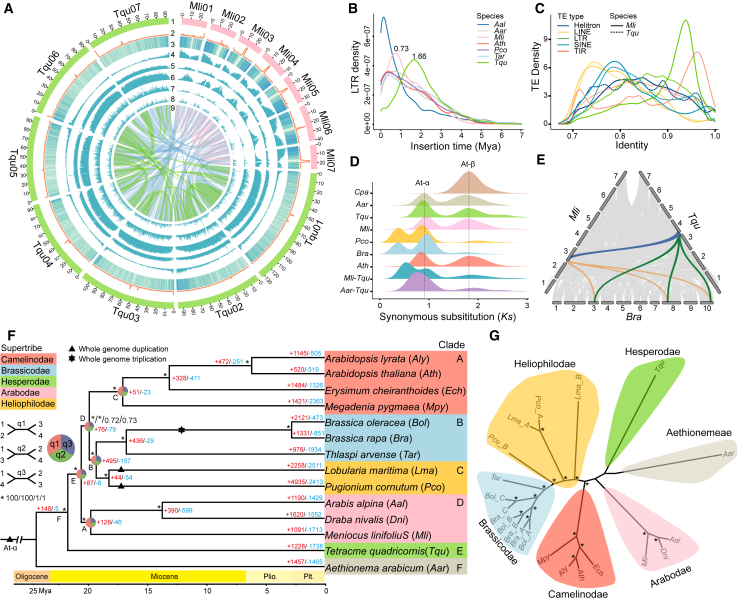

Figure 1.

Phylogenomic relationships among Brassicaceae.

(A) Genomic landscapes for Tetracme quadricornis (Tqu; left) and Meniocus linifolius (Mli; right). (1) Pseudo-chromosomes, (2) tandem repeats, (3) gene expression profiles of mixed leaf, root, stem, and flower samples, (4) GC content, (5) gene density, (6) repetitive sequences along chromosomes, (7) Copia density in 500-kb sliding window, (8) Gypsy density in 500-kb sliding window, (9) intra- (green and pink lines) and interspecies synteny (blue lines).

(B) Density and insertion time (mya) distribution for intact LTRs in seven Brassicaceae species. Aal, Arabis alpina; Aar, Aethionema arabicum; Ath, Arabidopsis thaliana; Pco, Pugionium cornutum; Tar, Thlaspi arvense.

(C) Distribution of sequence identity values between genomic copies and consensus repeats for different types of transposable elements (TEs) in Tqu and Mli assemblies.

(D) Synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) distributions of intra- and intergenomic syntenic blocks. At-α and At-β indicate the Brassicaceae- and Brassicales-specific WGD events, respectively. Cpa, Carica papaya; Bra, Brassica rapa. The younger peak observed in the Ks distribution for Mli-Tqu suggests a diversification corresponding to the split time between Mli and Tqu.

(E) Collinearity patterns among genomes of Tqu, Mli, and Bra. The green and orange wedges highlight an example of triplication of the Tqu (Chr4) and Mli (Chr3) genome segments in Bra (Chr3/8/10), and the blue wedge indicates the syntenic block between Tqu and Mli.

(F) A supertribe-level phylogeny for Brassicaceae. A maximum likelihood (ML) tree based on the concatenation of 1463 single-copy orthologous genes (SCOGs) identified with Orthofinder is shown, with estimated divergence times at the bottom. Bootstrap support values and posterior probabilities are marked with an ∗ indicating 100% support, and numbers indicate the real values for four datasets: concatenation-based with Orthofinder, concatenation-based with SonicParanoid, coalescence-based with Orthofinder, and coalescence-based with SonicParanoid. The black triangles and hexagon indicate the WGDs in Brassicaceae (At-α), Lobularia maritima (Lma), and Pco and the WGT (whole-genome triplication) in the most recent common ancestor of Bra and Bol, respectively. Numbers on the branches represent the numbers of expanded gene families (+, red) or contracted gene families (–, blue) among lineages. Pie charts at five internal nodes (A–E) show the frequency of three topologies (q1–q3, sector representations in different colors).

(G) A coalescence-based phylogeny based on 4434 syntenic genes. The A/B/C marks indicate the sub-genomes of Pco, Lma, Bra, and Bol. Bol, Brassica oleracea; Dni, Draba nivalis; Ech, Erysimum cheiranthoides.

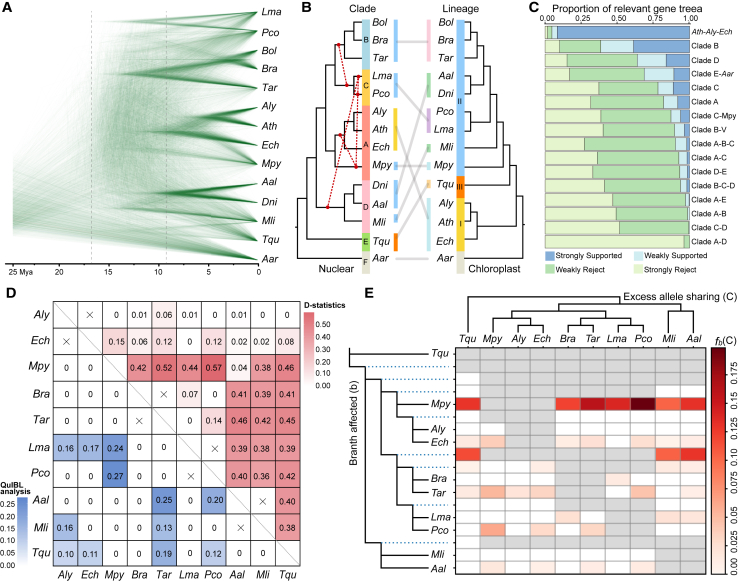

Figure 2.

Pervasive topology discordance, prevalent hybridization, and introgression in Brassicaceae.

(A) Cloudogram inferred from 1463 SCOGs (Orthofinder). Scale in mya.

(B) Extensive conflicts between plastome-based (right panel) and nuclear-genome-based (left panel) species ML trees using concatenated data. Introgression events are shown as broken red lines on the nuclear tree.

(C) Gene-tree compatibility as revealed by the portion of gene trees that are highly (weakly) supported or rejected. Weakly rejected refers to those not in the tree but compatible if low support branches (<75%) are contracted.

(D) Tests for introgression with D statistics (upper right panel) and QulBL analysis (lower left panel). Heatmaps of mean pairwise D per species pair and the mean total proportion of introgressed loci per species pair inferred with QuIBL.

(E) Test for introgression, with identification of excess sharing of derived alleles via the branch-specific statistic fb(C) approach. The branch-specific statistic fb(C) value indicates excess sharing of derived alleles between a given branch (b) on the y-axis, relative to its sister branch, and species C on the x-axis.

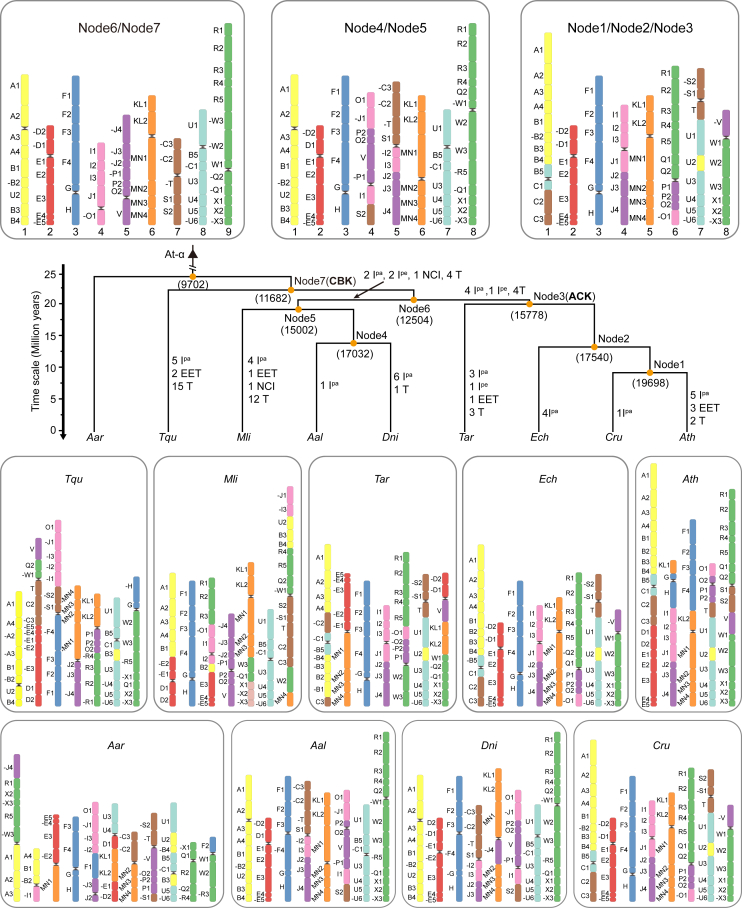

Figure 3.

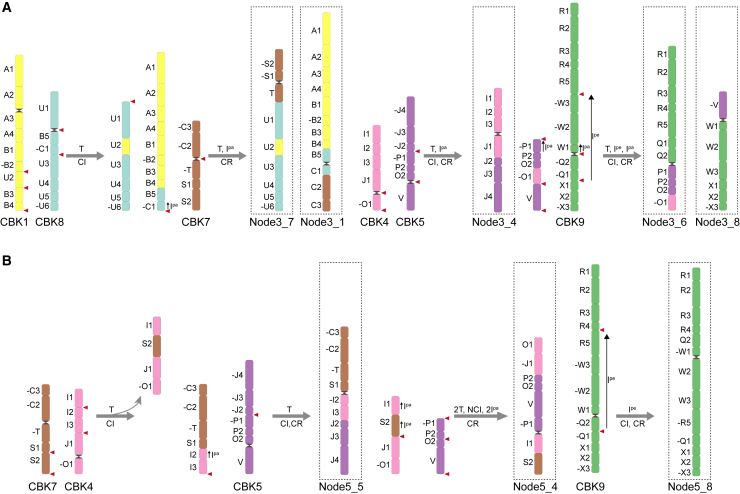

The ancestral core Brassicaceae karyotype (CBK) and the evolutionary history of Brassicaceae karyotypes.

Numbers in brackets indicate the conserved pPGs at each node (see supplementary Table 21). Rearrangement processes include nested chromosome insertions (NCI), end-to-end translocations (EET), and translocations (T), as well as paracentric (Ipa) and pericentric (Ipe) inversions. Black triangles indicate WGD events in Brassicaceae (At-α), and black sandglass-like symbols in karyotypes represent centromeres.

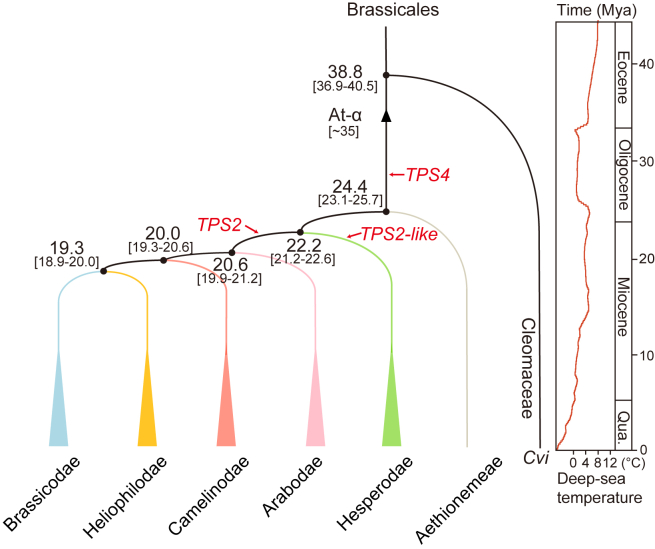

Figure 6.

A simplified model of evolutionary events in Brassicaceae.

After splitting from Aethionemeae, the progenitors of core Brassicaceae (colored triangles) diversified in a short period between 19.3 and 24.4 mya during the late Oligocene to the early Miocene. The first random duplication of TPS4s occurred after the At-α WGD. Two independent random duplication events doubled the TPS2-likes and TPS2s in Hesperodae and the MRCA of other supertribes (Brassicodae, Heliophilodae, Camelinodae, and Arabodae), respectively. The deep-sea temperatures are modified from Zachos et al. (2001).

Using a combination of homology-, transcriptome-, and ab initio-based predictive approaches, we annotated 33 038 and 27 225 protein-coding genes for Mli and Tqu (supplemental Figure 9; supplemental Table 8). For both species, >97% of the predicted protein-coding genes were functionally annotated using eight databases (supplemental Table 9). The proteomes were estimated to be >97.5% complete for both species on the basis of BUSCO assessments (supplemental Figure 10; supplemental Table 10). We also annotated 169 pseudogenes, 6074 rRNAs, 3751 tRNAs, 83 miRNAs, 98 snRNAs, and 185 snoRNAs in Mli and 194 pseudogenes, 4132 rRNAs, 1538 tRNAs, 109 miRNAs, 182 snRNAs, and 203 snoRNAs in Tqu (supplemental Tables 11 and 12).

The Mli and Tqu assemblies were composed of 38.74% (85.22 Mb) and 73.4% (524.22 Mb) transposable elements (TEs), respectively (supplemental Table 13). The most abundant repetitive elements were retrotransposons, which accounted for 51.19% and 60.9% of all repetitive sequences in Mli and Tqu. Retrotransposons accounted for 19.83% and 44.7% of the Mli and Tqu genome assemblies, and DNA transposons accounted for 17.31% and 26.63%. Tqu contained the most ancient LTR insertion at ∼1.66 mya, whereas Mli and the other five species contained insertions dating between 0.7 and 0.8 mya (Figure 1B). Corroborating the very recent burst history, the LTRs and terminal inverted repeats in Mli featured sequence identities between 90% and 100% (Figure 1C). An additional de novo annotation of two previously published Arabodae genomes, Arabis alpina (Aal) (Jiao et al., 2017) and Draba nivalis (Dni) (Nowak et al., 2021), revealed that all three genomes had similar TE compositions but varied in tandem repeat content (ranging from 4.78% in Dni to 9.13% in Mli) (supplemental Tables 13 and 14; supplemental Figure 11).

Genome sizes varied significantly among Hesperodae. Tetraploid Hesperis matronalis had the largest genome (8117 Mb) and diploid E. syriacum (Esy) had the smallest (256 Mb), which was approximately one-third the size of diploid Tqu (supplemental Table 13) (Kiefer et al., 2014; Mandakova et al., 2017; Hlouskova et al., 2019). Compared with Esy, Tqu contained approximately 2.2-fold more LTRs, 3.47-fold more helitrons, and longer introns (Wilcoxon test, P = 2e−10; supplemental Tables 13 and 15; supplemental Figures 12 and 13). These results suggest that variation in TE content and gene structure may contribute to genome size diversity in Hesperodae.

Two genomes free of extra WGD events

Two well-known features of Brassicaceae are the family-specific At-α WGD and the At-β WGD shared within Brassicales (Huang et al., 2020b; Walden et al., 2020b; Guo et al., 2021). To explore the genomic history of Mli and Tqu, we compared their genomes with those of five representative Brassicaceae species and the basal Brassicales species Carica papaya (Cpa) (Figure 1D). These species exhibited several WGD patterns. For example, A. thaliana (Ath; Camelinodae) and Aethionema arabicum (Aar; Aethionemeae) shared both the At-α and At-β WGDs; B. rapa (Bra; Brassicodae) and Pugionlum comutum (Pco; Heliophilodae) featured more recent polyploidization events (Cheng et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2021); and Cpa experienced only the At-β WGD (Edger et al., 2018). Both Mli and Tqu featured high levels of intragenomic synteny coincident with the At-α and At-β WGDs (Figure 1A; supplemental Figures 14 and 15). In addition, synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) distributions of homologous pairs from intra- and intergenomic syntenic blocks demonstrated that both genomes were free of extra WGDs (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 16). Finally, analysis of intergenomic synteny revealed that both Mli and Tqu exhibited syntenic depth ratios of 1:3 with B. rapa, whereas a 1:1 ratio persisted for Mli relative to Aal and Dni in Arabodae and Tqu relative to Esy in Hesperodae (Figures 1E; supplemental Figures 17 and 18).

A consistent phylogeny for core Brassicaceae supertribes

Recent research suggests that orthologous or single-copy nuclear sequences from de novo assemblies tend to be more accurate than those from either transcriptomic or targeted sequence-capture data (Hu et al., 2023). To characterize the phylogenomic relationships among supertribes of the core Brassicaceae, we selected chromosome-level genomes from 14 species representing all supertribes and the basal Aethionemeae. We identified 1463 shared single-copy orthologous genes (SCOGs) (supplemental Table 16). Highly supported (100% bootstrap values for all nodes) maximum-likelihood (ML) species trees were produced from the concatenated sequences using both nucleotide (all three codons or with third position removed) and amino acid sequences (Figures 1F; supplemental Figures 19 and 20). A coalescent-based analysis with individual gene trees after removal of nodes with bootstrap values <60% resulted in a topology identical to that of the concatenation-based analysis (supplemental Figure 21 and 22). Our results revealed that Hesperodae (Tqu) was sister to the remaining supertribes within the core Brassicaceae. Arabodae (Aal, Dni, and Mli) was a successive sister to Camelinodae, Brassicodae, and Heliophilodae, consistent with previous reports (Huang et al., 2016; Kiefer et al., 2019; Nikolov et al., 2019; Hendriks et al., 2023). Within Arabodae, Mli clustered with the two Arabideae species Aal and Dni. The rogue species Megadenia pygmaea (Mpy) of the tribe Biscutelleae, which is well known for having a contentious phylogenetic placement (Guo et al., 2021), was grouped within Camelinodae (Ath, A. lyrata, and Erysimum cheiranthoides) in our analysis. This result is in agreement with previous transcriptome- and genome-based phylogenies (Kiefer et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2021) but in conflict with other studies that place the species within Heliophilodae (Huang et al., 2016).

To minimize orthology inference errors, we next extracted 2546 SCOGs using SonicParanoid (Cosentino and Iwasaki, 2019). A concatenation-based phylogenomic reconstruction resulted in the same tree topology described above (Figures 1F; supplemental Figures 19, 20, and 23). However, a coalescent-based analysis using amino acid sequences resulted in Camelinodae being sister to Brassicodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae (supplemental Figure 24). We next performed a synteny-based phylogenomic reconstruction using 4344 collinear genes identified with the WGDI pipeline (Sun et al., 2022) using C. rubella as a reference (Slotte et al., 2013) (supplemental Figure 25). Again, the same topology was obtained, with the polyploidization histories clearly reflected for Bra, Bol, Lma, and Pco (Figure 1G; supplemental Figure 26) (Cheng et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2020a; Hu et al., 2021).

To minimize phylogenetic errors resulting from poor taxon sampling, we included up to 27 Brassicaceae species and used Cleome violacea (Cleomaceae) as the outgroup. With 1092 SCOGs, both concatenation- and coalescent-based methods produced consistent topologies (supplemental Figure 27). An additional expansion to 55 Brassicales genomes with 5217 low-copy orthologous genes generated a nearly identical topology, except that Mpy and Lunaria annua (Biscutelleae) moved from Camelinodae to Heliophilodae (supplemental Figure 28). However, the majority of nodes, especially deeper nodes of the core Brassicaceae, exhibited low support values, suggesting the presence of high levels of genomic complexity (Mandakova et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2021; Hendriks et al., 2023).

Despite such consistent core Brassicaceae tree topologies, phylogenetic discordance was frequently observed among nuclear gene trees (Figure 2), reflecting the complex evolutionary history of Brassicaceae. Indeed, analyses of internode certainty all (ICA) values and numbers of conflicting and concordant bipartitions revealed strong conflicts, especially in the deepest nodes of the core Brassicaceae (supplemental Figure 29). This pattern was easily observed in gene trees visualized with cloudogram through DensiTree (Bouckaert, 2010). These conflicts occurred mainly in the period between 10 and 15 mya (Figure 2A). The deeper nodes (A to E) of the core Brassicaceae were supported by around 50% of gene trees for Arabodae (node A, q1) or less for other nodes (q1; Figure 1F). In addition, the sister relationships among different supertribes were weakly, or sometimes strongly, rejected by >60% of relevant gene trees (Figure 2C). Thus, the core Brassicaceae supertribes featured a high level of phylogenomic complexity. We also identified pervasive incongruence between plastome- and nuclear-genome-based phylogenies (Figure 2B; supplemental Figures 30–32), a pattern previously reported in core Brassicaceae (Walden et al., 2020a, 2020b; Liu et al., 2020, 2024; Hendriks et al., 2023). This indicated that hybridization and/or ILS may have occurred during the early diversification of Brassicaceae.

Frequent hybridization and introgression during Brassicaceae evolution

At least four historical hybridization scenarios were identified in a network analysis (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 33). The strongest signal of gene flow occurred between Mpy and the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of supertribe Camelinodae and Pco. Other hybridizations were identified between the MRCA of Brassicodae and Heliophilodae. An ABBA-BABA-derived test (D statistic) (Malinsky et al., 2021) revealed significant introgressions in 86 of the 120 tested species triplets (three-taxon subtrees) (Z score > 3 and P < 0.002). The maximum pairwise D and f4-ratio statistics were observed for Mpy-Pco and Mpy-Tar (Thlaspi arvense) (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 34; supplemental Table 17). A derived Fbranch (fb) analysis identified a strong hybridization signal between Mpy and all other supertribes (Brassicodae, Hesperodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae), and other introgression events were identified between the MRCA of (Brassicodae + Heliophilodae) and Hesperodae/Arabodae (Figure 2E). Quantification of tree branch lengths with QulBL (Edelman et al., 2019) revealed that 15.8% of tested triplets featured significant hybridization signals (19 of 120, ΔBIC < –10), with the introgression gene trees having an average ratio of 17.4% (ranging from 9.91% for Tqu-Aly to 26.52% for Mpy-Pco; Figure 2D; supplemental Tables 18 and 19). A final calculation of the introgression intensity showed that deeper nodes had high reticulation indices, especially in supertribes Hesperodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae (supplemental Figure 35) (Cai et al., 2021). Collectively, these data suggest a complex history of hybridization and introgression during the early radiation of Brassicaceae, with Mpy likely being of hybrid origin.

Even so, we could not overlook the contribution of ILS. Estimation of theta, a parameter that reflects ILS levels (Cai et al., 2021), revealed high levels of ILS in node D and ancestor of Heliophilodae (supplemental Figure 36). A comparison between the real distribution of tree-to-tree distances and the simulated distribution of Robinson and Foulds tree-to-tree distances revealed a largely overlapping pattern (supplemental Figure 37) (Bogdanowicz et al., 2012). In addition, a strong positive correlation was observed between branch lengths and ICA values (Pearson’s correlation coefficient R = 0.96, P = 2.2e−16; supplemental Figure 38) (Zhou et al., 2022). These results suggest that ILS has at least partially contributed to the phylogenetic conflicts described above.

Ancestral core Brassicaceae karyotype (CBK)

We next reconstructed the ancestral karyotype of the MRCA for the core Brassicaceae using a synteny-based gene-family-clustering approach (Wu et al., 2023). Specifically, we used our reliable phylogeny based on high-quality genomes of nine diploid species representing major supertribes and the basal Aethionemeae, which have not undergone additional WGDs. We excluded species in Heliophilodae from reconstruction of the CBK because of their complex evolutionary history and potentially hybrid origin (Hendriks et al., 2023).

We first detected syntenic gene pairs between each of the 9 species. A minimum of 13 982 pairs were identified between Dni and Aar and a maximum of 20 472 pairs were found between Ath and Cru (supplemental Table 20). Next, we identified a total of 118 980 non-redundant syntenic groups, among which 9702 were conserved genes (putative protogenes, or pPGs) in all 9 species and represented a gene pool for the MRCA of the Brassicaceae. A total of 11 682 pPGs were present in 8 core Brassicaceae species, and 15 778 pPGs were found in 4 species representing supertribes Camelinodae and Brassicodae (supplemental Table 21). By analyzing the synteny between the 9 extant species and the previously predicted common ancestor for Brassicaceae (Schranz et al., 2006; Lysak et al., 2016), we refined the GB boundaries using the 9702 pPGs and identified 43 additional breakpoints dividing the 22 conserved GBs (Lysak et al., 2016) into 65 GBs, which were present in all 9 species (supplemental Figure 39; supplemental Table 22). Finally, with consideration of the phylogenetic topology and these 65 GBs, we built the karyotypes of extant species and traced the evolutionary scenario in Brassicaceae by reconstructing the ancestral karyotypes for all seven internal nodes (1–7) using Aar as the outgroup (Figure 3; Table 1). The predicted chromosomal pattern at node 7, i.e., the CBK, represents the ancestral karyotype of core Brassicaceae.

Table 1.

The ancestral core Brassicaceae karyotype

| CBK | GB | GB start | GB end | pPG start | pPG end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBK1 | A1 | AT1G01010 | AT1G08100 | AT1G01010 | AT1G07650 |

| A2 | AT1G08110 | AT1G12960 | AT1G08540 | AT1G12950 | |

| A3 | AT1G12970 | AT1G16610 | AT1G12970 | AT1G16610 | |

| A4 | AT1G16630 | AT1G19840 | AT1G16650 | AT1G19840 | |

| B1 | AT1G19850 | AT1G24256 | AT1G19850 | AT1G24140 | |

| B2 | AT1G24260 | AT1G27280 | AT1G24310 | AT1G27210 | |

| U2 | AT4G24160 | AT4G27730 | AT4G24740 | AT4G27540 | |

| B3 | AT1G27290 | AT1G30755 | AT1G27320 | AT1G30755 | |

| B4 | AT1G30757 | AT1G32750 | AT1G30760 | AT1G32750 | |

| CBK2 | D2 | AT1G61210 | AT1G56210 | AT1G61210 | AT1G56230 |

| D1 | AT1G64670 | AT1G61215 | AT1G64670 | AT1G61240 | |

| E1 | AT1G64960 | AT1G67270 | AT1G65020 | AT1G67260 | |

| E2 | AT1G67280 | AT1G71100 | AT1G67530 | AT1G71100 | |

| E3 | AT1G71110 | AT1G78310 | AT1G71110 | AT1G78310 | |

| E4 | AT1G78320 | AT1G79720 | AT1G78380 | AT1G79720 | |

| E5 | AT1G79730 | AT1G80950 | AT1G79730 | AT1G80950 | |

| CBK3 | F1 | AT3G01015 | AT3G07530 | AT3G01015 | AT3G07490 |

| F2 | AT3G07540 | AT3G12180 | AT3G07540 | AT3G12180 | |

| F3 | AT3G12190 | AT3G16010 | AT3G12200 | AT3G16010 | |

| F4 | AT3G16020 | AT3G25520 | AT3G16050 | AT3G25470 | |

| G | AT2G05170 | AT2G07690 | / | / | |

| H | AT2G10940 | AT2G20900 | AT2G13810 | AT2G20890 | |

| CBK4 | I1 | AT2G20920 | AT2G25260 | AT2G20930 | AT2G25050 |

| I2 | AT2G25270 | AT2G27540 | AT2G25800 | AT2G27170 | |

| I3 | AT2G27550 | AT2G31035 | AT2G27900 | AT2G31010 | |

| J1 | AT2G31040 | AT2G35850 | AT2G31060 | AT2G35610 | |

| O1 | AT4G00026 | AT4G03190 | AT4G00026 | AT4G03190 | |

| CBK5 | J4 | AT2G41420 | AT2G48150 | AT2G41420 | AT2G48080 |

| J3 | AT2G37670 | AT2G41417 | AT2G37670 | AT2G41290 | |

| J2 | AT2G35860 | AT2G37660 | AT2G35880 | AT2G37650 | |

| P1 | AT4G12620 | AT4G09680 | AT4G12620 | AT4G09830 | |

| P2 | AT4G09670 | AT4G07390 | AT4G09610 | AT4G08280 | |

| O2 | AT4G03200 | AT4G05450 | AT4G03200 | AT4G05430 | |

| V | AT5G47810 | AT5G42130 | AT5G47540 | AT5G42340 | |

| CBK6 | KL1 | AT2G01060 | AT2G05160 | AT2G01060 | AT2G04410 |

| KL2 | AT3G25540 | AT3G32960 | AT3G25540 | AT3G30340 | |

| MN1 | AT3G42180 | AT3G52970 | AT3G42880 | AT3G52960 | |

| MN2 | AT3G52980 | AT3G56550 | AT3G52990 | AT3G56550 | |

| MN3 | AT3G56560 | AT3G59550 | AT3G56570 | AT3G59520 | |

| MN4 | AT3G59570 | AT3G63530 | AT3G59600 | AT3G63530 | |

| CBK7 | C3 | AT1G53720 | AT1G56190 | AT1G53730 | AT1G56140 |

| C2 | AT1G47960 | AT1G53710 | AT1G47980 | AT1G53710 | |

| T | AT4G12700 | AT4G16240 | AT4G12840 | AT4G16230 | |

| S1 | AT5G42110 | AT5G39890 | AT5G42080 | AT5G39900 | |

| S2 | AT5G39880 | AT5G32470 | AT5G39860 | AT5G36210 | |

| CBK8 | U1 | AT4G16250 | AT4G24150 | AT4G16250 | AT4G24150 |

| B5 | AT1G32760 | AT1G37130 | AT1G32760 | AT1G36310 | |

| C1 | AT1G43020 | AT1G47940 | AT1G43190 | AT1G47720 | |

| U3 | AT4G27740 | AT4G32990 | AT4G27745 | AT4G32780 | |

| U4 | AT4G33000 | AT4G35730 | AT4G33560 | AT4G35730 | |

| U5 | AT4G35733 | AT4G38100 | AT4G35740 | AT4G38100 | |

| U6 | AT4G38120 | AT4G40100 | AT4G38120 | AT4G40100 | |

| CBK9 | R1 | AT5G23000 | AT5G19350 | AT5G22940 | AT5G19350 |

| R2 | AT5G19340 | AT5G13390 | AT5G19330 | AT5G13390 | |

| R3 | AT5G13380 | AT5G08540 | AT5G13360 | AT5G08540 | |

| R4 | AT5G08535 | AT5G06740 | AT5G08535 | AT5G06750 | |

| R5 | AT5G06730 | AT5G01010 | AT5G06440 | AT5G01030 | |

| W3 | AT5G56550 | AT5G60800 | AT5G56550 | AT5G60800 | |

| W2 | AT5G49620 | AT5G56540 | AT5G49920 | AT5G56530 | |

| W1 | AT5G47820 | AT5G49610 | AT5G47820 | AT5G49580 | |

| Q2 | AT5G26220 | AT5G23010 | AT5G26220 | AT5G23010 | |

| Q1 | AT5G30510 | AT5G26230 | AT5G28910 | AT5G26230 | |

| X1 | AT5G60805 | AT5G63090 | AT5G60820 | AT5G63090 | |

| X2 | AT5G63100 | AT5G65925 | AT5G63120 | AT5G65910 | |

| X3 | AT5G65930 | AT5G67640 | AT5G65950 | AT5G67640 |

CBK1–9, pseudochromosomes of the CBK; GB, genomic block, named corresponding to the 22 ACK blocks with numbers indicating the breakdown of each ACK block; pPGs, putative protogenes conserved in all nine extant species.

In contrast to the 8 pseudochromosomes of the ACK, the CBK is characterized by 9 haploid chromosomes. This finding is consistent with a recent study that included only 3392 strictly conserved syntenic genes (supplemental Figure 40) (Walden and Schranz, 2023). The karyotypes for node 1 to node 3 are identical, and so also for node 4 and node 5. Notably, node 6 has the same pattern as the CBK (Figure 3). These results imply relatively short divergence times between node 1 and node 3, node 4 and node 5, and the CBK and node 6. It is noteworthy that the karyotype of node 3, the common ancestor of Camelinodae and Brassicodae, is nearly identical to that of the ACK, with only a few GBs having undergone inversion (Figures 3 and 4). Overall, we observed considerable consistency between the CBK and the ACK. Specifically, three pseudochromosomes of node 3 (_2/_3/_5) correspond to the three ancestral chromosomes of the CBK (CBK2/3/6). By contrast, node 3_1 and node 3_7 originated from CBK1/8/7, and node 3_4/_6/_8 were derived from CBK4/5/9, respectively. This transformation occurred through a series of translocations, including both paracentric and pericentric inversions (Figure 4A). Similarly, five pseudochromosomes of node 5 (_1/_2/_3/_6/_7) appear to have remained in their ancestral states, whereas the remaining three (_4/_5/_8) are derived from four translocations, one nested chromosome insertion, two paracentric inversions, and one pericentric inversions (Figure 4B). Because there is only one high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly available (Tqu), we were unable to infer the ancestral genome for Hesperodae. However, a comparison between the Tqu genome and the reconstructed ancestral karyotype for Hesperodae (CEK, n = 7) with a comparative cytogenetic approach (Mandakova et al., 2017) revealed extensive chromosomal rearrangements, with all Tqu chromosomes having undergone batches of rearrangements (supplemental Figure 41). Finally, frequent centromere repositioning may have occurred (supplemental Table 23), consistent with previous reports (Mandakova et al., 2020).

Figure 4.

Karyotype evolutionary scenarios from the CBK to node 3 (A) and node 5 (B).

Rearrangement processes include nested chromosome insertions (NCI), end-to-end translocations (EET), and translocations (T), as well as paracentric (Ipa) and pericentric (Ipe) inversions. Black sandglass-like symbols represent centromere locations. Red triangles denote the positions of genomic fission or fusion.

Previous research has reported chromosome counts of both n = 7 and n = 8 for Mli, with n = 8 being more frequent in Alysseae (Spaniel et al., 2015). This phenomenon has also been observed in Camelina microcarpa, likely owing to variation among different genetic populations (Brock et al., 2022). Interestingly, the ancestors of node 4 (Arabideae) and node 5 (Arabodae) had chromosome counts of n = 8 (Figure 3). Compared with Aal and Dni, two species also in Arabodae, Mli seems to have experienced more intense chromosomal recombination, resulting in a decrease in chromosome number to seven from the ancestral state of eight. More specifically, the ancestral node 5_2 chromosome in Mli is divided into two segments, each of which is fused to the Mli_1 and Mli_3 chromosomes, respectively (Figure 3; supplemental Figure 42). Similarly, extensive chromosomal rearrangements were identified in Mpy (supplemental Figure 43). Considering its ancient hybridization history, jumped phylogenomic position, and shared PCK-specific chromosomes with Pco, the diploid Mpy appears to have originated from homoploid hybridization between node 3 (ACK; n = 8) and ancPCK (n = 8) (Guo et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2021).

Expansion and expression diversification of class I TPS genes

We next evaluated whether any genes or gene families were associated with the early Brassicaceae radiation by searching for node-specific gene family expansion and contraction patterns (nodes A–F; Figure 1F; supplemental Figures 44–48; supplemental Tables 24–29). Among these nodes, only a small number of gene families were found to be expanded or contracted. The most significant expansion (495 families) and contraction (157 families) occurred at node B, the MRCA of supertribes Brassicodae and Heliophilodae (Figure 1F). Gene ontology analysis revealed that defense-related genes were significantly enriched at nodes B, C, and E (supplemental Figures 45, 46, and 48). Node F (the MRCA of core Brassicaceae) was enriched for genes encoding TPS enzymes, as well as genes related to several other pathways (Figure 5A).

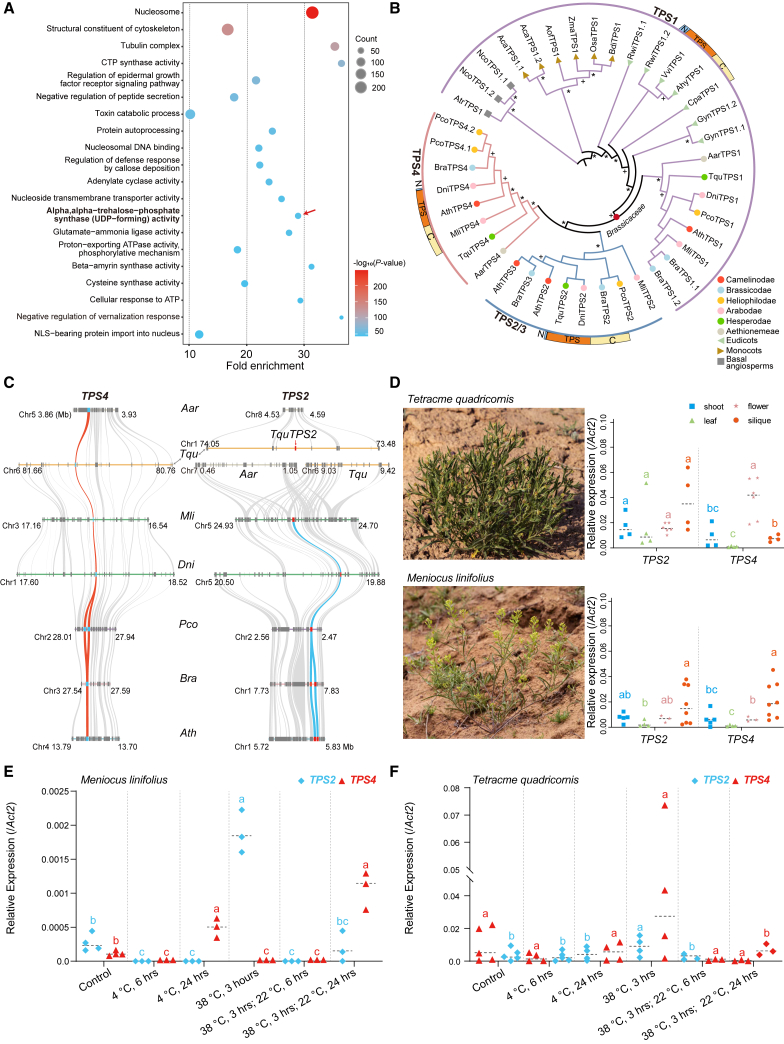

Figure 5.

Brassicaceae-specific expansion of Trehalose-6-Phosphate (T6P) synthase 1 (TPS1) genes.

(A) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment of molecular functions for expanded gene families on node F (Figure 1F) corresponding to the split between core Brassicaceae and Aethionemeae. GO terms in bold and marked with red arrows highlight the expansion of trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P) synthase-related genes.

(B) An ML tree shows the phylogenetic clustering of class I TPS proteins in 19 angiosperms, including 7 Brassicaceae species representing all supertribes and the basal Aethionemeae. The ∗ and + indicate bootstrap supports of >90% and 50%–90%, respectively. The summarized protein structure for each subgroup is shown, with N, TPS, and C indicating the N-terminal domain, TPS domain, and C-terminal domain, respectively. Supertribes or outgroups are indicated with colored circles, triangles, and squares, as shown at the bottom right.

(C) The collinearity relationships of subgroups TPS2 and TPS4 in Brassicaceae. The red and blue curves show the positions and syntenic relationships of TPS2 (red squares) and TPS4 (blue squares) between selected species. Gray curves show the surrounding syntenic genes between species.

(D) Relative expression patterns of TPS2s and TPS4s in different tissues (right panels) of plants grown under natural conditions in Fukang County, Xinjiang Province, China. A minimum of four biological replicates of leaves, shoots, flowers, and siliques were collected and pooled from at least five individuals of each species (left panels).

(E and F) Relative expression patterns of TPS2s and TPS4s under fluctuating temperature conditions for Mli(E) and Tqu(F). A minimum of three biological replicates were used for each assay. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA, P < 0.05).

TPS genes encode enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of T6P, a signaling molecule involved in the regulation of abiotic stress tolerance and developmental processes such as flowering time and embryo development (Fichtner and Lunn, 2021). A. thaliana has 11 TPS genes that form 2 distinct classes: I (TPS1 to TPS4) and II (TPS5 to TPS11) (Leyman et al., 2001; Avonce et al., 2006; Lunn, 2007). Phylogenetic and synteny analyses revealed that TPS1 is highly conserved and exhibits good collinearity between Brassicaceae and C. violacea (Cleomaceae), whereas TPS2 to TPS4 are present only in Brassicaceae (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 49; supplemental Table 30). As collinearity was not identified between TPS1s and TPS4s (supplemental Figure 50), TPS4 was likely generated by random duplication of TPS1 in the MRCA of Brassicaceae and stably inherited with very good collinearity in core Brassicaceae. Notably, Pco contains two copies (PcoTPS4.1 and PcoTPS4.2), which are tandemly duplicated on chromosome 2 (Figure 5B and 5C). TPS2-like genes are expanded in Hesperodae (Tqu) and the remaining core Brassicaceae supertribes via two independent random duplication events. The TquTPS2 locus on chromosome 1 exhibits good synteny with Aar chromosome 4, whereas no TPS2-like sequence was identified in the blocks harboring TPS2-like genes in supertribes Camelinodae, Brassicodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae. Tandemly duplicated TPS3s were detected only in Arabidopsis and Brassica (Figure 5B). All the Brassicaceae TPS2 and TPS4 proteins lacked the N-terminal domain, which harbors a nuclear localization signal that targets the AthTPS1 protein primarily to the nucleus (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 51) (Fichtner et al., 2020). By contrast, nearly all Brassicaceae TPS1s contain the N-terminal domain. These results suggest that the Brassicaceae-specific TPS2- and TPS4-like genes may have different evolutionary histories.

In Arabidopsis, class I TPSs have catalytic activity (Van Dijck et al., 2002). TPS1 is broadly expressed, TPS2 and TPS4 are expressed at low levels and exclusively in developing seeds, and TPS3, a potential pseudogene, is only minimally expressed (supplemental Figures 52 and 53) (Vandesteene et al., 2010). Both TquTPS1 and MliTPS1 were highly and nearly universally expressed in all tissues sampled from wild plants harvested in Xinjiang, China (supplemental Figure 54). A similar pattern was observed for AthTPS1 (supplemental Figure 52). Despite their extremely low levels of expression under laboratory conditions, both MliTPS2 and MliTPS4 were expressed at relatively high levels in siliques and seeds sampled from plants growing under fluctuating natural conditions (Figure 5D and 5E). These results suggest that TPS2 and TPS4 genes from supertribes Camelinodae, Brassicodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae may exhibit similar expression patterns. TquTPS4 is expressed at relatively high levels in flowers (Figure 5D), indicating that this gene may play a role in the regulation of flower development. Notably, these TPS genes exhibit diverse expression patterns under fluctuating temperatures (Figure 5F). The lineage-specific expansion of class I TPSs was thus followed by diversification of expression, and likely function, during the early evolution of Brassicaceae.

Discussion

Because of the economic and scientific importance of Brassicaceae, its phylogeny and genome evolution remain at the forefront of plant evolutionary biology. Here, we generated high-quality chromosome-level genome assemblies for two species representing supertribes Hesperodae and Arabodae and identified the complex genomic features that accompanied the early evolution of Brassicaceae.

Using available high-quality genomes representing all supertribes and the basal Aethionemeae, we produced a phylogeny consistent with recent reports (Huang et al., 2016; Kiefer et al., 2019; Nikolov et al., 2019; Hendriks et al., 2023). Overall, Hesperodae (Tqu) appears to have diverged successive to the basal Aethionemeae (Aar) followed by supertribes Camelinodae, Brassicodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae in the late Oligocene to early Miocene (19.3–24.4 mya; Figure 1). Intriguingly, this was coincident with the accelerated uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, which was followed by significant aridity in the Asian interior and monsoon intensification in Eastern Asia (Kagale et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2022). These results thus link the diversification of Brassicaceae to global environmental change.

The observed phylogenetic discordances correspond well with the complex evolutionary history of Brassicaceae, in which frequent and ancient inter-supertribe hybridizations have been identified (Figure 2). Such patterns, marked by extensive gene-tree heterogeneity, have been documented previously and can result from rampant hybridization events between members of closely or distantly related groups (Nikolov et al., 2019; Hendriks et al., 2023). Furthermore, the influence of ILS during early radiation, leading to low resolution of deeper nodes within Brassicaceae, cannot be overlooked. Therefore, reducing such groups exclusively to existing models that strictly adhere to bifurcating trees significantly oversimplifies the reality and hinders our ability to accurately describe the evolutionary process (Cai et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2023; Hendriks et al., 2023).

The availability of high-quality diploid genomes without additional WGD events for species representing nearly all major supertribes as well as the basal Aethionemeae makes it possible to reconstruct the CBK (Table 1; Figures 3 and 4). The previously proposed ACK is based mainly on genomes representing Camelinodae and Brassicodae (Schranz et al., 2006; Lysak et al., 2016). Using the ACK, phylogenomic variation and chromosomal evolution have been characterized in Brassicodae (PCK, n = 7) (Mandakova and Lysak, 2008; Cheng et al., 2013) and Hesperodae (CEK, n = 7) (Mandakova et al., 2017) and tribes Thlaspideae (Bayat et al., 2021), Biscutelleae (Geiser et al., 2016; Mandakova et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2021), and Arabideae (Willing et al., 2015; Mandakova et al., 2020), as well as basal Aethionemeae (Walden et al., 2020a). Very recently, Walden and Schranz (2023) reported their effort in reconstruction of the ancestral karyotype covering the major clades (Walden and Schranz, 2023). Their ancestral karyotype reconstruction, which also features 9 haploid chromosomes, largely aligns with our CBK, albeit with less resolution and significant structural differences (supplemental Figure 40). This is very likely due to the identification of fewer strictly conserved syntenic genes (3392 compared with our 9702) caused by the segmental genome of Esy (Jiao et al., 2017). Alternatively, inclusion of the rogue Mpy genome, which features significant hybridization and has a contentious phylogenetic position, may have lowered the accuracy of their effort.

Although the ACK represents essentially just the ancestors of Camelinodae and Brassicodae (Schranz et al., 2006; Lysak et al., 2016), its 22 GBs are well conserved throughout Brassicaceae (supplemental Figure 39; supplemental Table 22). Compared with the 8 chromosomes of ACK, the CBK exhibits a more ancestral state with 9 chromosomes and 65 GBs (Figures 3 and 4; supplemental Figure 39; Table 1). It is noteworthy that the reconstructed ancestral karyotype for node 3 (the common ancestor of Camelinodae and Brassicodae) is highly consistent with the ACK and also with the extant Cru and Ech, indicating the accuracy of our analyses. However, to fully resolve the ancestral karyotype for the whole family, a suitable high-quality genome at the chromosome-level for Cleomaceae is still necessary. Nonetheless, our data provide a valuable resource and a foundation for more in-depth comparative analyses of genome evolution in Brassicaceae.

The available high-quality genomes and phylogeny enabled us to more comprehensively evaluate the molecular features associated with the Brassicaceae radiation, especially during the late Oligocene to early Miocene. Our analyses in angiosperms revealed that, after the At-α WGD, Brassicaceae specifically duplicated its class I TPS1 into TPS4s (Figures 5 and 6). However, this expansion seems not to align well with the known WGD radiation lag-time model (Schranz et al., 2012). The divergence between core Brassicaceae and the basal Aethionemeae during the late Oligocene and early Miocene is coincident with the accelerated uplift of the Tibetan Plateau. The uplift was followed by increasing aridity in the Asian interior, intensifying Eastern Asian monsoons, fluctuating daily temperatures (Zachos et al., 2001; Kagale et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2022), as well as increased diversification in Brassicaceae. This geologic period also saw two independent random duplications: TPS4-like produced the TPS2/3-like genes in Hesperodae and the successive supertribes Camelinodae, Brassicodae, Arabodae, and Heliophilodae, respectively (Figure 6). It should be noted that duplication of class I TPS genes seems to be an evolving and highly dynamic process, as demonstrated by a further tandem duplication of TPS2/3-like genes in Camelinodae and Brassicodae. Intriguingly, the duplicated TPS2/3-like and TPS4-like genes exhibit highly varied expression under both natural and disturbed temperatures, a signal of functional diversification (Figure 5). However, the precise molecular and genetic connections between these duplications and paleoclimatic changes require further in-depth study.

The assembly of high-quality genomes for Hesperodae and Arabodae provides fresh insights into the ancestral karyotypes and molecular features associated with the complex evolutionary history of Brassicaceae. The lineage-specific and dynamic expansion of key flowering-time regulators may have served as an evolutionary gate, with more efficiency and precision, to sense and respond to fluctuating energy availability under ever-changing environmental conditions.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA sequencing

Seeds of M. linifolius (Mli) (voucher ID TanDY0110) and T. quadricornis (Tqu) (voucher ID TanDY0709) were collected in Karamay City and Fukang City, respectively, in Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China. The seeds were preserved in the Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. For genome sequencing, seeds were cultured on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium and grown under long-day conditions. Fresh leaves were harvested from each single plant for genomic DNA extraction.

For short-read sequencing, 150-bp paired-end reads were generated using the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, USA) at ∼50×. For long-read sequencing, Single-Molecule Real-Time PacBio Genome Sequencing was performed using the PacBio Sequel II platform with the circular consensus sequencing model (Pacific Biosciences). After quality control, we obtained 38.3 and 52.4 Gb of high-quality HiFi reads for Mli (∼147.3×) and Tqu (∼72.3×), respectively (supplemental Table 2). For scaffolding, Hi-C sequencing was performed to generate ∼100× data for both species. For genome annotation, total RNA from mixed samples (including young leaves, stems, roots, and flowers) was used for both Illumina paired-end (150 bp) and full-length Nanopore long-read (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) sequencing.

Genome size estimation and assembly

Genome sizes were initially estimated using flow cytometry with Solanum lycopersicum (0.88 Gb) as a reference. In brief, approximately 20 mg of fresh leaves were harvested and placed in a Petri dish containing 1 ml of ice-cold nuclei isolation buffer (45 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 20 mM MOPS, 30 mM Na3C6H5O7, 1% [w/v] PVP 40, 0.2% [v/v] Triton X-100, 10 mM Na2 EDTA [pH 7.0]). The tissues were minced with a sterile razor blade, mixed, and filtered through a 42-μm nylon mesh into a sample tube. Later, a stock DNA fluorochrome solution was added together with 50 mg/ml PI and 50 mg/ml RNase, and the mixture was incubated on ice prior to analysis. Sample measurement and data analysis were performed using a BD FACScalibur and Modifit (v3.0), respectively (Duda et al., 1999). All measurements were carried out in triplicate, and mean values are reported. Genomic surveys were performed using Jellyfish (v2.2.10) (Marcais and Kingsford, 2011) and GenomeScope2 (Vurture et al., 2017) with k-mer = 19 and 50× Illumina short reads. High-quality circular consensus sequencing reads were used for genome assembly with default parameters of the hifiasm (v0.12) pipeline (Cheng et al., 2021). Contigs were scaffolded using ∼100× Hi-C data according to previously described methods. In brief, the Hi-C data were filtered, mapped, and evaluated using HiC-pro (v2.10.0) (Servant et al., 2015) and BWA (v0.7.10-r789) (Li and Durbin, 2009). Next, LACHESIS was used to cluster and reorder the corrected contigs into pseudochromosomes (Burton et al., 2013), using the following parameters: cluster min re sites = 22, cluster max link density = 2, cluster non-informative ratio = 2, order min n res intrun = 10, order min n res in shreds = 10.

Genome quality assessment

The quality and completeness of both genome assemblies were assessed using three approaches. We first judged assembly quality by mapping back the Illumina reads to the genomes using default parameters of BWA-MEM (Li, 2013). Next, the assemblies were subjected to BUSCO (v5.4) analysis (Simao et al., 2015). Finally, the LTR assembly indices of the two genomes were evaluated using published procedures (Ou et al., 2018; Ou and Jiang, 2018).

Annotation of repetitive sequences

Tandem repeats were identified with TRF (v4.07) using the parameters: 1 1 2 80 5 200 2000 -d -h (Benson, 1999). Simple sequence repeats were identified with MISA (v2.1) (Beier et al., 2017). Next, we performed de novo and homology-based prediction to detect TEs. The Extensive de novo TE Annotator (EDTA) pipeline (v2.0.1) (Ou et al., 2019), integrating RepeatMasker (Tarailo-Graovac and Chen, 2009), LTR_Finder (Xu and Wang, 2007), LTRharvest (Ellinghaus et al., 2008), and LTR_retriever (Ou and Jiang, 2018), was used to classify the TEs as DNA transposons or retrotransposons. Lineages for the Copia and Gypsy superfamilies were identified using Tesorter (Zhang et al., 2022). The insertion time (T) of each type of intact LTR retrotransposon was estimated using the formula T = K/2r with a substitution rate (r) of 8.22 × 10−9 substitutions per site per year (Kagale et al., 2014) and K representing the genetic distance.

Gene annotation

Gene annotation was performed using ab initio, homology-based, and transcriptome-based predictive methods after masking of all repetitive regions. For ab initio prediction, Augustus (v2.4) (Stanke and Waack, 2003) and SNAP (v2006-07–28) (Korf, 2004) were used with default parameters. Five Brassicaceae species (A. thaliana [Arabidopsis Genome, 2000], B. napus [Song et al., 2020], B. nigra [Perumal et al., 2020], D. nivalis [Nowak et al., 2021], and Isatis indigotica [Kang et al., 2020]) were used for homology-based prediction with GeMoMa (v1.7) (Keilwagen et al., 2018). For transcriptome-based prediction, Trinity (v2.11) (Grabherr et al., 2011) and PASA (v2.0.2) (Haas et al., 2003) were used to generate de novo assemblies, and Hisat (v2.0.4) (Kim et al., 2015), Stringtie (v1.2.3) (Pertea et al., 2015), and GeneMarkS-T (v5.1) (Tang et al., 2015) were used to predict transcripts and genes. All gene models were integrated using EVidenceModeler (v1.1.1) (Haas et al., 2008) to generate a consensus gene set. To obtain untranslated regions and alternatively spliced isoforms, we used PASA to update the gff3 file (two rounds). Finally, BUSCO (v5.4) was used to assess the completeness of the gene set.

Functional annotations were assigned to protein-coding genes by performing BLAST (v2.2.31) searches against the NR, GO, KEGG, KOG, and TrEMBL databases (Ye et al., 2006) with an e value cutoff of 10−5. We also used Blast2GO (v4.1) (Conesa and Gotz, 2008) to search the GO and KEGG databases.

Four types of non-coding RNAs (microRNAs, transfer RNAs, ribosomal RNAs, and small nuclear RNAs) were annotated using tRNAscan-SE (v1.3) (Lowe and Eddy, 1997) for tRNA, Rfam (v12.0) (Kalvari et al., 2018) and Infernal (v1.1) (Nawrocki and Eddy, 2013) for snoRNA and snRNA, Rfam (v12.0) (Kalvari et al., 2018) and Barrnap (v 0.9) for rRNA, and miRbase (Kozomara et al., 2019) for miRNA. Pseudogenes were predicted with GeBlastA (v1.0.4) (She et al., 2009) and GeneWise (v2.4.1) (Birney et al., 2004).

Gene family classification and analyses

On the basis of recently published tree topologies (Huang et al., 2016; German et al., 2023; Hendriks et al., 2023), we selected 14 diploid species with high-quality chromosome-level assemblies (supplemental Table 16) representing all 5 supertribes of core Brassicaceae and the basal Aethionemeae. These included A. thaliana (Arabidopsis Genome, 2000), A. lyrata (Hu et al., 2011), M. pygmaea (Yang et al., 2021), and E. cheiranthoides (Zust et al., 2020) in Camelinodae; B. rapa (Belser et al., 2018), B. oleracea (Belser et al., 2018), and T. arvense (Geng et al., 2021) in Brassicodae; Lobularia maritima (Huang et al., 2020a) and P. cornutum (Hu et al., 2021) in Heliophilodae; M. linifolius (this study), A. alpina (Willing et al., 2015), and D. nivalis (Nowak et al., 2021) in Arabodae; T. quadricornis (this study) in Hesperodae; and the Aethionemeae species A. arabicum (Nguyen et al., 2019).

Orthofinder (v2.5.4) (Emms and Kelly, 2019) was used to identify putative gene families. For genes with alternative splicing variants, the longest transcript was selected. Protein sequence alignments were obtained with MAFFT (v7.475) (Katoh and Standley, 2013) and converted into the corresponding codon alignments with PAL2NAL (Suyama et al., 2006). TrimAL (v1.4, -gt 0.8 -cons 80) (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009) was used to extract the conserved sites of the multiple sequence alignments. The PhyloSuite (v1.2.2) pipeline (Zhang et al., 2020) was used to concatenate the alignments into a super matrix. ML trees were generated with IQ-TREE (v2.1.2, -m MFP -bb 1000) (Nguyen et al., 2015). We skipped the divergence time estimation and followed the results of Hendriks et al. (2023), with the exception of the divergence time between B. rapa and B. oleracea (2.5–3.2 mya), which was obtained from TimeTree (Kumar et al., 2017). Gene family expansion and contraction were evaluated using CAFÉ (v5) (De Bie et al., 2006) based on a Poisson distribution. Genes in significantly expanded families were used for GO enrichment analysis with clusterProfiler (Wu et al., 2021).

WGD history prediction

Six species (A. thaliana, B. rapa, P. cornutum, M. linifolius, T. quadricornis, and A. arabicum) representing each Brassicaceae clade, as well as C. papaya (Yue et al., 2022) representing the basal Brassicales, were selected for WGD analyses. Syntenic blocks and collinear genes within and between species were identified using WGDI (0.5.6) with the parameter “-icl” (Sun et al., 2022). Ks values between collinear genes were estimated using the Nei-Gojobori approach implemented in PAML (v4.9) (Yang, 2007). Genes with Ks < 0.15 were excluded from further analysis. Median Ks values in each syntenic block were fitted for peak identification in WGDI using the “-pf” option. To justify the ploidy levels, we used dot plots of collinear genes and syntenic blocks to determine syntenic ratios between species.

Phylogenic analyses in Brassicaceae

We used both Orthofinder (v2.5.4) (Emms and Kelly, 2019) and SonicParanoid (Cosentino and Iwasaki, 2019) to identify orthologous genes for phylogenic reconstruction with both coalescent- and concatenation-based analyses at the nucleotide and protein levels. In total, six different alignments for each gene family were used to perform phylogenetic analyses: (1) amino acid alignments of Orthofinder genes, (2) amino acid alignments of SonicParanoid genes, (3) nucleotide alignments of Orthofinder genes, (4) nucleotide alignments of SonicParanoid genes, (5) nucleotide codon alignments with the third position removed for Orthofinder genes, and (6) nucleotide codon alignments with the third position removed for SonicParanoid genes. Because concatenated datasets do not account for the stochasticity of the coalescent process, we used ASTRAL (v5.7.8) (Zhang et al., 2018) to reconstruct the coalescent tree. The ASTRAL pipeline is statistically consistent under the multi-species coalescent model and is thus useful for handling ILS. Individual ML gene trees were constructed using IQ-TREE, with the same parameters listed above. For stem group nodes, we checked the bootstrap support values with 1000 simulations and summarized the topologies with bootstrap support values ≥0%, 10%, 30%, or 60%. To minimize errors resulting from poor taxon sampling, up to 28 species were added, including 27 Brassicaceae species and one Cleomaceae species (C. violacea) as an outgroup. Another species tree containing an additional 55 Brassicales species was analyzed with STAG (Emms and Kelly, 2018) using the low-copy gene set (shared ortholog groups) to further verify the stability of our phylogenetic structure. First, we used Orthofinder to cluster gene families based on the annotated proteins of 55 species, resulting in 5217 gene families shared among all species. Next, we built gene trees for each of these 5217 gene families using FastTree (Price et al., 2009). Lastly, we used STAG (Emms and Kelly, 2018) to build the final species tree based on the 5217 gene trees.

To minimize ortholog identification errors, synteny-based orthologous gene relationships were evaluated with WGDI, which does not require gene-family clustering. In addition to the 14 species mentioned previously, C. rubella (Slotte et al., 2013) was also included as a reference because its karyotype has been suggested to be similar to the ACK (Lysak et al., 2016). We identified intergenomic syntenic blocks between C. rubella and each species and intragenomic syntenic blocks within each species. On the basis of the similarity (Ks and BLAST scores) and completeness (covered genes and spanned gene length) of each syntenic block, the WGDI pipeline (-bi and -a) was used to assign syntenic blocks into putative sets. Genes exhibiting collinear relationships to C. rubella were used to infer the collinear gene tree with IQ-TREE. Finally, the synteny-based species tree was constructed with ASTRAL.

Plastome assembly and phylogenetic reconstruction

To investigate maternal phylogenetic relationships, we assembled and annotated the plastomes using GetOrganelle (v1.7.2a) (Jin et al., 2020) and PGA (Qu et al., 2019). The inverted repeat and coding region boundaries of each annotated gene were determined with Geneious (v9.0.2) (Kearse et al., 2012). The protein-coding sequences of the 14 species mentioned above, as well as other Brassicales species, were extracted, aligned, and concatenated using Phylosuite. ML trees were constructed with IQ-TREE using the settings -bb 1000 -m MFP.

Phylogenetic discordance assessment

To evaluate nuclear gene-tree discordance, we calculated the ICA to quantify the degree of conflict between the species and gene trees at each node. ICA values close to 1 indicate strong concordance for the bipartition defined by a given internode, whereas ICA values close to 0 indicate strong conflict. Negative ICA values suggest a conflict for the defined bipartition with other high-frequency bipartitions (Salichos et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2022). ICA values were estimated in RAxML (v8.2.12) (Stamatakis, 2014), and the tree generated with ASTRAL was used as the species tree. Quartet frequencies of the internal branches of the species tree were calculated using ASTRAL (t = 8), and gene-tree compatibility (whether sister groups of each other) was analyzed with DiscoVista (v1.0) for each combination. Phyparts (Smith et al., 2015) was used to summarize the number of conflicting and concordant bipartitions between the species tree and the individual gene tree. To visualize the conflicts, we built a cloudogram using DensiTree (v2.2.6) (Bouckaert, 2010), and the input gene trees were time-calibrated with TreePL (v1.0) (Smith and O'Meara, 2012).

Detection of ancient hybridization, gene flow, and ILS

We first inferred the species network for modeling both ILS and introgression with the maximum pseudo-likelihood pipeline PhyloNet (v3.8.4) using the InferNetwork_MPL command (Than et al., 2008). Network searches were performed by allowing between one and four reticulation events and using 10 runs for each search. To estimate the optimum number of reticulations, we optimized the branch lengths and inheritance probabilities and computed the likelihood of the best-scored network for each of the three maximum reticulation event searches. Next, we used QuIBL, which compares branch length distributions across gene trees, to test hypotheses regarding whether phylogenetic discordance between all possible triplets could be explained by ILS alone or by a combination of ILS and introgression (Edelman et al., 2019). The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to test whether the discordance between gene and species trees was due more to ILS or introgression. We used a stringent cutoff of ΔBIC < −10 to accept the ILS+ introgression model, as suggested by the authors.

Next, we performed an ABBA-BABA test using Dsuite (v0.5) (Malinsky et al., 2021) with a four-taxon statement ((H1, H2)H3)H4). Using H4 as the outgroup (herein A. arabicum), H1 and H2 were treated as sister species, and H3 was tested for potential gene flow or introgression with H1 or H2. The number of sites with ABBA and BABA allele patterns were tallied. D was calculated as (nABBA − nBABA)/(nABBA + nBABA), in which nABBA and nBABA represent the total number of sites with ABBA and BABA patterns, respectively. A negative D indicates gene flow between H1 and H3, a positive D indicates gene flow between H2 and H3, and D = 0 indicates no gene flow. The f4-admixture ratio and fb statistic were calculated for all trios using Fbranch in the Dsuite pipeline. The fb statistic is a heuristic strategy to summarize f4-admixture ratios over the entire tree topology, including internal branches, to detect introgression events and excess allele sharing across a dataset (Malinsky et al., 2021). For these analyses, all genome sequences were first aligned to the reference Arabidopsis genome using BWA (v0.7.10-r789) and then sorted and converted with SAMtools (v0.1.19) (Danecek et al., 2021) to generate summary statistics. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms were identified with GATK (v3.7) (McKenna et al., 2010). The resulting VCF file was used as input for Dsuite and further analyzed using A. arabicum as an outgroup. Finally, a “Reticulation Index” was generated to measure the frequency of the asymmetrical triplets in all combinations at each node to quantify the intensity of introgression using 28 species datasets via a recently reported pipeline (Cai et al., 2021).

However, ILS could not be excluded as a contributor to the observed gene tree discordances. We tested the population mutation parameter theta of each internal branch using mutation units inferred by IQ-TREE and coalescent units inferred by ASTRAL. Theta reflects the level of ILS, with a high theta value indicating a large ancestral population size and hence a high level of ILS (Cai et al., 2021). Next, 10 000 gene trees were simulated under the ILS hypothesis with the MSC model using Phybase (v1.4) in R (v4.2.1) (Liu and Yu, 2010). The Robinson-Foulds distance distribution (Bogdanowicz et al., 2012) between the species tree and the simulated gene trees, and those between the species tree and the empirical gene trees, were compared. Finally, correlations between branch lengths and ICA values were calculated to determine the contribution of ILS to tree conflicts. In general, the shorter the branch length, the more ILS and conflicts among gene trees (Zhou et al., 2022).

Reconstruction of the CBK

To reconstruct the CBK, we selected nine diploid species without additional WGDs. These species represent four major supertribes (Camelinodae, Brassicodae, Hesperodae, and Arabodae) and the basal Aethionemeae: A. thaliana, C. rubella, E. cheiranthoides, T. arvense, A. alpina, D. nivalis, M. linifolius, T. quadricornis, and A. arabicum. Given its complex evolutionary history and potential hybrid origin, Heliophilodae was excluded from the reconstruction of the CBK (Hendriks et al., 2023). The CBK was reconstructed as follows. Initially, syntenic gene pairs were identified between each pair from the nine species using MCscan (Python version) in “--full” mode to extract one-to-one quota syntenic blocks (Tang et al., 2008). Subsequently, these syntenic gene pairs were categorized into syntenic groups with the synteny-based gene-family clustering pipeline SynPan, using merge.pl for clustering and transform_stat.pl for summarization (Wu et al., 2023). Considering the syntenic groups and the phylogenetic tree (Figure 3) of the species under investigation, we deduced the strictly conserved syntenic genes (putative protogenes, or pPGs) at each node of the phylogenetic tree. This facilitated the identification of an MRCA for the Brassicaceae pool, which comprises 9702 core pPGs conserved across all investigated species. Third, by collinearity analysis between 9 extant species and the ACK with MCscan, we revisited 22 conserved syntenic GBs of the ACK (Schranz et al., 2006; Lysak et al., 2016) in these species. Moreover, 43 additional breakpoints were identified by the addition of genomic data (supplemental Figure 39). Then, using 9702 pPGs, we refined the boundaries of these syntenic blocks to obtain 65 conserved GBs. We built the karyotypes of extant species based on these 65 GBs. Finally, with the topology and 65 conserved GBs, we reconstructed the CBK and traced the evolutionary scenario of karyotypes in Brassicaceae using MLGO, which is based on a PMAG method (Hu et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2017). In addition, centromere positions were predicted using quartet (Lin et al., 2023) and previous reports (Willing et al., 2015; Lysak et al., 2016; Mandakova et al., 2020; Naish et al., 2021; Nowak et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021).

RNA extraction and gene expression analyses

For tissue-specific expression assays, leaves, shoots, flowers, and siliques were collected in early May 2022 from plants growing wild in Fukang City, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China. For temperature-response analyses, seeds of M. linifolius and T. quadricornis were collected from plants grown in Fukang City, Xinjiang, China, and A. thaliana seeds (Col-0) were collected from plants grown under long-day conditions (16-h light and 8-h dark, 22°C). After disinfection with 75% ethanol, the seeds were sown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium and stratified at 4°C for 3 days. Ten days after germination under long-day conditions, control plants were maintained under the same growth conditions, whereas experimental plants were subjected to either 6 or 24 h of low temperature (4°C) in a refrigerator or 3 h of high temperature (38°C) in a water bath. After treatment, a portion of the plants were immediately sampled, and the other portion was placed back under the same conditions as the control group for an additional 6 or 24 h before sampling. Each assay was carried out using 3 to 5 biological replicates, with approximately 10 plants per replicate.

Total RNA isolation and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT–PCR) were performed as described previously (Zhong et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2023). In brief, total RNA was isolated from shoots and leaves with TRI Reagent TR118 (MRC, USA) and from flowers and siliques with an OmniPlant RNA Kit (CWBio, China). A total of 1 μg of RNA was treated with gDNA Purge (Novoprotein, China) to remove contaminating genomic DNA and reverse transcribed using NovoScript Plus All-in-one 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Novoprotein, China). Gene expression analyses were carried out with gene-specific primers (supplemental Table 27) at an amplification efficiency of between 90% and 110% using NovoStart SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus on a QuantStudio Real-Time PCR apparatus. ACT2 was used as a reference. Primer information can be found in supplemental Table 31.

Data and code availability

All data supporting the results of this study are included in the manuscript and its supplemental files. Genome assemblies, annotations, and sequence data were deposited in the CNSA database (https://db.cngb.org) under project number CNP0003993.

Funding

This work was supported by the Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) (Grant No. XDA0440000 and XDB31000000).

Author contributions

J.-Y.H. and D.-Z.L. conceptualized and coordinated the project. J.L. and B.-Y.Z. collected the samples and performed the main experiments. J.L., S.-Z.Z., Y.-L.L., and B.-Y.Z. analyzed and visualized the data with the help of all other authors. J.-Y.H. wrote the manuscript with input from J.L. and D.-Z.L. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guli Mayem, Haiyang Ma, Kaiqing Xie, Hoja Tore, and Musen Lin from Xinjiang Agricultural University for their help with field work. We are grateful to Jun He, Chun-Fang Li, and Shu-Lan Chen for their help in nursing and propagating the plants. We appreciate useful discussions with Lian-Ming Gao, Jun-Bo Yang, Peng-Fei Ma, Yan-Xia Jia, Rong Zhang, Shui-Yin Liu, and Sheng-Yuan Qin. We greatly appreciate the four anonymous reviewers for their very insightful comments and suggestions on improving the manuscript. This work was partially facilitated by GBOWS and the iFlora HPC Center of GBOWS. No conflict of interest declared.

Published: March 11, 2024

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Jin-Yong Hu, Email: hujinyong@mail.kib.ac.cn.

De-Zhu Li, Email: dzl@mail.kib.ac.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- Al-Shehbaz I.A., Beilstein M.A., Kellogg E.A. Systematics and phylogeny of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae): an overview. Plant Syst. Evol. 2006;259:89–120. doi: 10.1007/s00606-006-0415-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Blanco C., Aarts M.G.M., Bentsink L., Keurentjes J.J.B., Reymond M., Vreugdenhil D., Koornneef M. What has natural variation taught us about plant development, physiology, and adaptation? Plant Cell. 2009;21:1877–1896. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés F., Coupland G. The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13:627–639. doi: 10.1038/nrg3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmetti Y., Luhmann N., Bérard S., Tannier E., Chauve C. Comparative Methods for Reconstructing Ancient Genome Organization. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1704:343–362. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7463-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avonce N., Mendoza-Vargas A., Morett E., Iturriaga G. Insights on the evolution of trehalose biosynthesis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C.D., Koch M.A., Mayer M., Mummenhoff K., O'Kane S.L., Jr., Warwick S.I., Windham M.D., Al-Shehbaz I.A. Toward a global phylogeny of the Brassicaceae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2142–2160. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat S., Lysak M.A., Mandáková T. Genome structure and evolution in the cruciferous tribe Thlaspideae (Brassicaceae) Plant J. 2021;108:1768–1785. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier S., Thiel T., Münch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilstein M.A., Al-Shehbaz I.A., Kellogg E.A. Brassicaceae phylogeny and trichome evolution. Am. J. Bot. 2006;93:607–619. doi: 10.3732/ajb.93.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilstein M.A., Al-Shehbaz I.A., Mathews S., Kellogg E.A. Brassicaceae phylogeny inferred from phytochrome A and ndhF sequence data: tribes and trichomes revisited. Am. J. Bot. 2008;95:1307–1327. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser C., Istace B., Denis E., Dubarry M., Baurens F.C., Falentin C., Genete M., Berrabah W., Chèvre A.M., Delourme R., et al. Chromosome-scale assemblies of plant genomes using nanopore long reads and optical maps. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:879–887. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Clamp M., Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowicz D., Giaro K., Wróbel B. TreeCmp: Comparison of Trees in Polynomial Time. Evol Bioinform. 2012;8:475–487. doi: 10.4137/Ebo.S9657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert R.R. DensiTree: making sense of sets of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1372–1373. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock J.R., Mandáková T., McKain M., Lysak M.A., Olsen K.M. Chloroplast phylogenomics in Camelina (Brassicaceae) reveals multiple origins of polyploid species and the maternal lineage of C. sativa. Hortic. Res. 2022;9 doi: 10.1093/hr/uhab050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]