Significance

Aberrant activation of AKT and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) have emerged as central promoters of tumorigenesis. AKT activation follows the loss or mutation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a tumor suppressor defective in breast and other cancers. PARP1 is overexpressed in breast tumors and contributes to aberrant DNA repair, promoting the survival and proliferation of tumor cells. However, the connection between the AKT and PARP1 pathways remain unclear. We show glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (EPRS1), an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase elevated in mammary tumors, exerts a noncanonical function linking these pathways. AKT activation in breast cancer cells, directs nuclear localization of EPRS1, which binds PARP1, enhances protein ADP-ribosylation, and facilitates cancer cell survival. The AKT–EPRS1–PARP1 axis represents an anticancer therapeutic target.

Keywords: EPRS1, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, AKT, PARP1, ADP-ribosylation

Abstract

Glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (EPRS1) is a bifunctional aminoacyl-tRNA-synthetase (aaRS) essential for decoding the genetic code. EPRS1 resides, with seven other aaRSs and three noncatalytic proteins, in the cytoplasmic multi-tRNA synthetase complex (MSC). Multiple MSC-resident aaRSs, including EPRS1, exhibit stimulus-dependent release from the MSC to perform noncanonical activities distinct from their primary function in protein synthesis. Here, we show EPRS1 is present in both cytoplasm and nucleus of breast cancer cells with constitutively low phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression. EPRS1 is primarily cytosolic in PTEN-expressing cells, but chemical or genetic inhibition of PTEN, or chemical or stress-mediated activation of its target, AKT, induces EPRS1 nuclear localization. Likewise, preferential nuclear localization of EPRS1 was observed in invasive ductal carcinoma that were also P-Ser473-AKT+. EPRS1 nuclear transport requires a nuclear localization signal (NLS) within the linker region that joins the catalytic glutamyl-tRNA synthetase and prolyl-tRNA synthetase domains. Nuclear EPRS1 interacts with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), a DNA-damage sensor that directs poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) of proteins. EPRS1 is a critical regulator of PARP1 activity as shown by markedly reduced ADP-ribosylation in EPRS1 knockdown cells. Moreover, EPRS1 and PARP1 knockdown comparably alter the expression of multiple tumor-related genes, inhibit DNA-damage repair, reduce tumor cell survival, and diminish tumor sphere formation by breast cancer cells. EPRS1-mediated regulation of PARP1 activity provides a mechanistic link between PTEN loss in breast cancer cells, PARP1 activation, and cell survival and tumor growth. Targeting the noncanonical activity of EPRS1, without inhibiting canonical tRNA ligase activity, provides a therapeutic approach potentially supplementing existing PARP1 inhibitors.

Glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (EPRS1) is a mammalian bifunctional aminoacyl-tRNA-synthetase (aaRS) with a glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GluRS) domain near the N terminus and a prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProRS) domain at the C-terminus (1, 2). EPRS1 resides in a cytoplasmic multi-tRNA synthetase complex (MSC) that harbors nine tRNA synthetases and three auxiliary proteins, AIMPs 1 to 3 (3). The principal function of EPRS1 is ligation of glutamate or proline to cognate tRNAs for protein synthesis. EPRS1, like several other aaRSs, exhibits noncanonical functions distinct from protein synthesis. In myeloid cells, interferon-γ induces EPRS1 phosphorylation and release from the MSC to join three other proteins to form the GAIT (interferon-gamma-activated inhibitor of translation) complex that inhibits translation of a family of inflammation-related transcripts (2, 4). In adipocytes, insulin stimulates EPRS1 binding to fatty acid transport protein 1 and fatty acid uptake, contributing to adiposity and aging (5). Virus infection directs EPRS1 binding to PCBP2 to suppress viral replication (6). SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, directs the assembly of a complex of EPRS1 and three other aaRSs stimulating virus translation (7). Biallelic mutations in EPRS1 have been implicated in neurological disease, e.g., hypomyelinating leukodystrophy, as well as diabetes and bone disease (8, 9).

EPRS1 levels are associated with progression of breast and other cancers. EPRS1 was identified as a serum antigen found primarily in breast and colon cancer patients (10). EPRS1 was up-regulated in human breast tumors from estrogen receptor (ER)+ patients, due largely to increased gene copy number (11). Moreover, elevated EPRS1 expression is associated with reduced overall survival of patients with ER+ breast tumors. EPRS1 expression also correlated inversely with relapse-free survival in monotherapy tamoxifen-treated patients (11). The mechanisms by which EPRS1 influences breast tumor growth remain unclear. Pharmacological inhibition of EPRS1 by halofuginone, a ProRS inhibitor, or by EPRS1-specific shRNA, caused the death of breast cancer cells, consistent with a role of EPRS1 in tumor cell survival (12). An association of EPRS1 with nonbreast tumors has been shown in gastric cancer and predicts poor prognosis (13).

The genes encoding key signal transduction pathway proteins, PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase), and AKT, the PI3K target kinase, are among the most frequently mutated in human cancers (14–16). Their contribution to breast cancer is substantial; in a study of 75 breast cancer patients, 35% had mutations in one of the three genes, and mutations were biomarkers for tumor aggressiveness (17). Here, we explore the mechanism by which the PI3K/PTEN/AKT signaling pathway contributes to the tumor-promoting influence of EPRS1 in breast cancer. We report an unexpected finding that stress-mediated activation of AKT induces nuclear localization of EPRS1 where it binds and activates the tumor-promoting protein, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1).

Results

Nuclear Localization of EPRS1 in PTEN– Breast Cancer Cell Lines.

We considered the possibility of altered localization of EPRS1, which is primarily cytoplasmic, in breast cancer cells. Localization was investigated in breast cancer cell line lysates by cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation. The robust appearance of nuclear EPRS1 was observed in four of eight cell lines—MDA-MB-468, HCC38, HCC70, and HCC1937 cells (Fig. 1A). EPRS1 remained primarily cytoplasmic in MCF-7, MDA-MB-157, MDA-MB-231, and T-47D cells. The cell lines with elevated nuclear EPRS1 are PTEN–, whereas cells with low nuclear EPRS1 are PTEN+. MDA-MB-468 cell lysates were subjected to further subcellular fractionation; EPRS1 was present in the soluble nuclear fraction, but not in the chromatin-bound fraction detected with an antibody against DNA-binding histone, H3 (Fig. 1B). Cytoplasmic EPRS1 is primarily localized in the ~1.5 MDa MSC with seven other aaRSs and AIMPs 1, 2, and 3 (3). Cytoplasmic and soluble nuclear fractions of MDA-MB-468 cells were size-fractionated by Superose 6 column chromatography. EPRS1 in cytoplasmic fractions was primarily in high molecular weight (MW) fractions up to ~1.5 MDa, consistent with the MSC (Fig. 1C). Coelution of two other MSC constituents, methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MARS1; nomenclature: we use 1-letter amino acid abbreviation followed by ARS1) and AIMP1, in high MW fractions confirmed MSC localization. In soluble nuclear fractions, EPRS1 was absent from the highest MW fraction, but found in fractions ranging from ~150 to ~1,000 kDa, suggesting EPRS1 interaction with other proteins since the majority is in fractions larger than the 171 kDa monomer, or a twice-as-large dimer (3). AIMP1 and MARS1 were also present in lower MW nuclear fractions, consistent with reports of nuclear MSC constituents (18, 19).

Fig. 1.

Nuclear localization of EPRS1 in breast cancer cells. (A) Isolation of cytosolic and nuclear fractions of PTEN+ and PTEN– breast cancer cell lines and EPRS1 immunoblot. Nuclear fractions were detected with anti-p84 antibody and cytoplasmic fractions with anti-α-tubulin antibody. (B) Immunoblot determination of EPRS1 in subcellular fractions of MDA-MB-468 cells. Cell fractions were detected as in A; anti-histone H3 and anti-Na+/K+-ATPase detected nuclear chromatin and membranes, respectively. (C) Size-exclusion chromatography of cytosolic and nuclear lysates of MDA-MB-468 cells. (D) Schematic of major mammalian EPRS1 domains (Top). Intracellular localization of EPRS1 domains expressed in HEK293T cells (Bottom) was detected with nuclear (anti-HDAC) and cytosolic (anti-α-tubulin) marker. (E) Sequence alignment of potential EPRS1 NLS in multiple species (Top). Nuclear localization of FLAG-EPRS1 bearing NLS mutation 4K>4A in HEK293T cells (Bottom).

Human EPRS1 is a dual-function aaRS with N-terminus GST-like and GluRS domains joined to a C-terminus ProRS domain by a linker containing three tandem repeats of helix-turn-helix WHEP-TRS domains (20, 21) (Fig. 1 D, Top). To determine the domain required for nuclear localization, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged constructs expressing the linker alone, or the linker with the GST-like and GluRS domains (termed GluRS-linker), and the linker with the ProRS domain (linker-ProRS). All EPRS1 regions, including the linker by itself, localized within the nucleus suggesting a nuclear localization signal (NLS) within the linker (Fig. 1 D, Bottom). A putative NLS containing four tandem Lys residues between amino acids 963 to 966 was predicted by bioinformatic analysis; the sequence is conserved in mammals and possibly in other vertebrates (Fig. 1 E, Top). FLAG-tagged, full-length EPRS1 bearing a mutation in which the Lys residues were mutated to Ala (p.K963_K966delinsAAAA or 4K>4A) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Following over-expression in HEK293T cells, substantial wild-type (WT) EPRS1 was nuclear-localized, whereas the 4K>4A mutant protein was exclusively cytoplasmic, confirming the NLS function (Fig. 1 E, Bottom). A similar result was observed in MDA-MB-486 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

EPRS1 Nuclear Localization Is PI3K/AKT-Dependent.

A primary function of PTEN is the inactivation of AKT, mediated by dephosphorylation of PIP3, the phospholipid activator of AKT, to the inactive PIP2. We investigated the role of the PTEN–AKT axis in EPRS1 nuclear localization. siRNA-mediated PTEN knockdown in MCF-7 cells activated AKT, as shown by Ser473 phosphorylation, and increased EPRS1 nuclear localization (Fig. 2A). A specific PTEN inhibitor, bpV (HOpic), exhibited similar activities (Fig. 2B). The influence of stresses that activate AKT, namely, oxidative stress and heat shock (22–24), on EPRS1 nuclear localization was investigated. H2O2-mediated oxidative stress (Fig. 2C) and heat shock (Fig. 2D) treatments directed nuclear accumulation of EPRS1 in PTEN+ MCF-7 cells. Two MSC constituent aaRSs observed in the nucleus under certain conditions, i.e., KARS1 and MARS1, did not translocate to the nucleus following heat shock stress, indicating target specificity (Fig. 2D) (25–27). Nuclear localization of several non-MSC residents was also determined, including three previously reported in the nucleus, namely, SARS1, YARS1, and WARS1 (28–30). SARS1 exhibited low-level nuclear localization under basal conditions, but none showed stress-inducible relocalization, suggesting a marked specificity for EPRS1. The generality of PTEN-regulated EPRS1 nuclear localization in other species and cell types was investigated in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). EPRS1 was primarily cytoplasmic in Ptenfl/fl control MEFs, but heat shock induced marked nuclear enrichment (Fig. 2 E, Top). EPRS1 was nuclear-localized in untreated Pten−/− fibroblasts (Fig. 2 E, Bottom). To directly test the role of the PI3K/AKT pathway, the effects of BKM120, a pan-PI3K inhibitor (Fig. 2 F, Left), and MK2206, an AKT inhibitor (Fig. 2 F, Right), on EPRS1 nuclear localization were determined. Heat shock induced AKT phosphorylation in MCF-7 cells as shown in NIH 3T3 cells (23). Both inhibitors suppressed AKT phosphorylation and, importantly, inhibited EPRS1 nuclear localization. SC79, a small-molecule activator of AKT (31), and insulin (32) both increased AKT Ser473 phosphorylation and induced EPRS1 nuclear localization even in the absence of stress (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

AKT-dependent nuclear localization of EPRS1. (A) siRNA-mediated knockdown of PTEN in MCF-7 cells induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation (Right) and EPRS1 nuclear localization (Left). (B) A PTEN inhibitor, bpV (HOpic) (20 mM) induced EPRS1 nuclear localization in MCF-7 cells. (C) Treatment of MCF-7 cells with 400 µM H2O2 for 10 min induced EPRS1 nuclear localization. (D) Heat shock treatment of MCF-7 cells at 43 °C for 1 h induced nuclear localization of EPRS1, but not other MSC (Left) and non-MSC (Right) aaRSs. (E) Nuclear localization was determined in MEFs from WT (Ptenf1/f1, Top) or Pten−/− knockout (Bottom) mice after 43 °C heat shock for 1 h. (F) Heat-shocked MCF-7 cells were treated for 24 h with the pan-PI3K inhibitor BKM120 (100 nM, Left) or the pan-AKT inhibitor MK2206 (100 nM, Right) (or with DMSO solvent control), and EPRS1 nuclear localization was determined. (G) The effect of AKT activation on EPRS1 nuclear localization was determined following treatment with insulin and SC79, a small-molecule activator of AKT. (H) Cellular localization of EPRS1 and P-Ser473-AKT was determined by immunofluorescence in breast cancer and tumor-adjacent tissue (Left). Nuclear fluorescence intensity of EPRS1 was quantitated in seven tumor samples and six tumor-adjacent samples (mean ± SEM, P < 0.01, Right). Nuclear fractions were detected with anti-p84 and cytoplasmic fractions with anti-α-tubulin antibodies.

Increased AKT Ser473 phosphorylation is seen in invasive ductal carcinoma and other breast cancers and is a prognostic negative indicator of survival (33, 34). Human-invasive ductal carcinoma was subjected to immunofluorescence analysis. As expected, tumor tissues, but not tumor-adjacent tissues, exhibited robust cytoplasmic P-Ser473-AKT signal (Fig. 2 H, Left). Importantly, robust detection of EPRS1 was observed in nuclei of ductal carcinoma tissue but not in tumor-adjacent tissue. Quantitation revealed an ~threefold enrichment of nuclear EPRS1 in the P-AKT+ tumors compared to P-AKT– tumor-adjacent tissue (Fig. 2 H, Right), supporting an in vivo role for the PI3K/AKT pathway in EPRS1 nuclear localization.

Nuclear Interaction of EPRS1 with PARP1 and Activation of Poly-ADP Ribosylation.

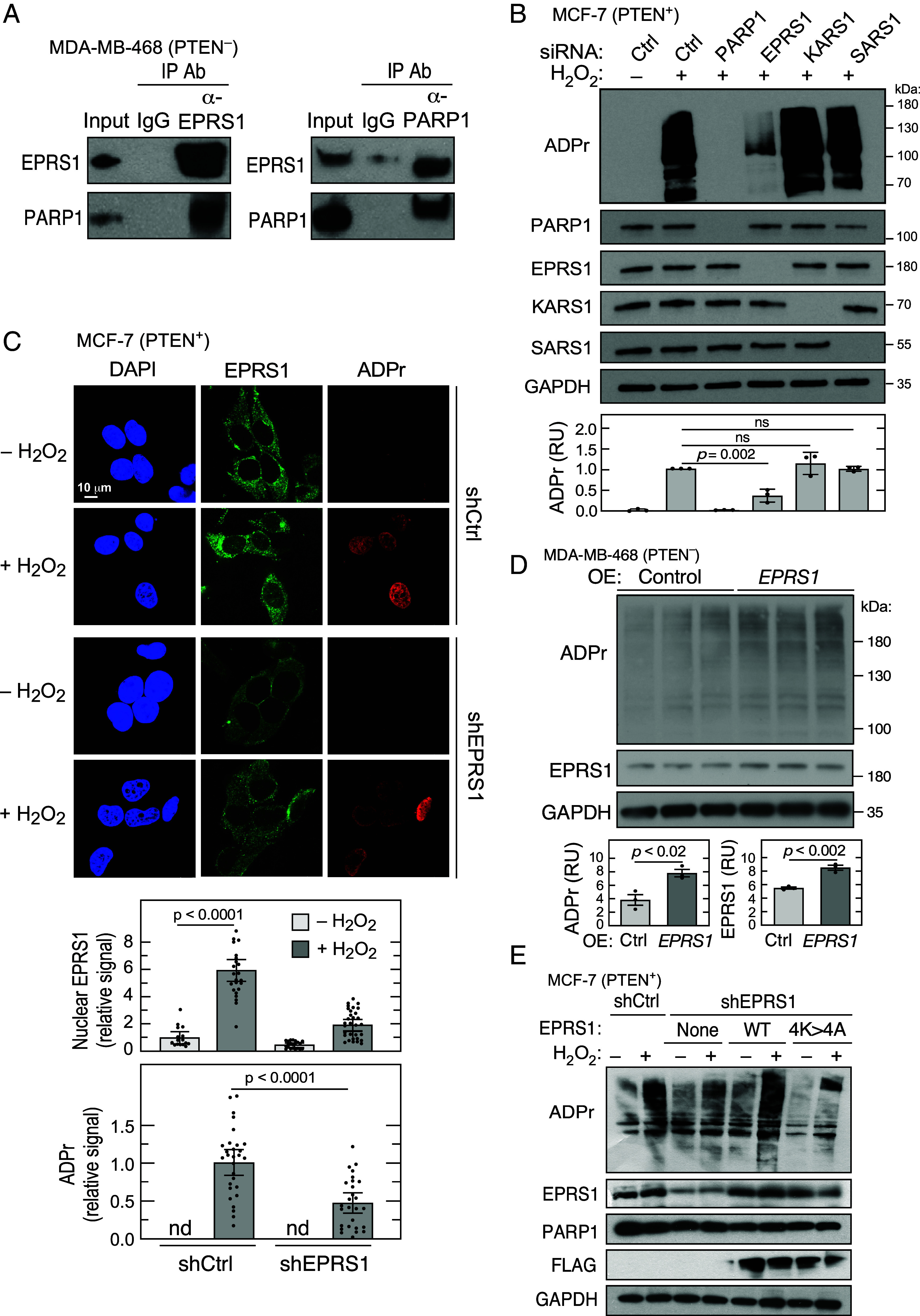

To interrogate the nuclear function of EPRS1, interacting proteins were investigated. Nuclear lysates of MDA-MB-468 cells were subjected to immuno-pulldown with anti-EPRS1 antibody, SDS-PAGE, and LC-MS/MS analysis. Eighteen proteins were found to have spectral counts >10 and >6-fold enrichment compared to isotype-specific IgG pulldown (SI Appendix, Table S1). Seven proteins were aaRS constituents of the MSC, consistent with reports showing MSC-resident aaRSs in the nucleus (18, 19). The remaining are primarily established nuclear-resident proteins. We focused on the interaction of EPRS1 with PARP1, a master regulator of DNA damage repair pathways and a promoter of tumor development (35–37). Pulldown of PARP1, followed by LC-MS/MS, verified the interaction with EPRS1 (SI Appendix, Table S2). Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed the interaction of EPRS1 and PARP1 in nuclear lysates of MDA-MB-468 cells (Fig. 3A), supporting the coelution of EPRS1 and PARP1 by size fractionation (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 3.

EPRS1 contributes to PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation and gene expression. (A) Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments show interaction of EPRS1 and PARP1 in nuclear fractions. (B) Determination of ADP-ribosylation (ADPr) in total cell extracts of MCF-7 cells subjected to siRNA-mediated knockdown of PARP1, EPRS1, KARS1, and SARS1. The cells were incubated with H2O2 for 10 min and subjected to immunoblot analysis. (C) Immunofluorescence detection of ADPr and EPRS1 localization in shControl and shEPRS1 MCF-7 cells treated with H2O2. Image Pro Plus software was used to analyze EPRS1 and ADPr fluorescence signal (n = 16 to 30 cells, mean ± SEM). (D) Effect of EPRS1 over-expression on ADPr in MDA-MB-468 cells. (E) Role of EPRS1 NLS in activation of PARP1 ADP-ribosylation activity in shEPRS1 knockdown cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged WT and 4K>4A EPRS1 cells.

PARP1 posttranslationally modifies nuclear proteins by attachment of NAD+-derived poly(ADP-ribose) (ADP ribosylation), primarily at Glu, Asp, and Lys residues (37). To investigate the potential influence of EPRS1 on PARP1 activity, MCF-7 cells were subjected to siRNA-mediated knockdown, then treated with H2O2 to activate PARP1 and induce poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, i.e., PARylation, of target proteins (38, 39). ADP-ribosylation (ADPr) was assessed by immunoblot with anti-ADPr antibody. H2O2-mediated induction of ADP-ribosylation was completely abrogated by PARP1 knockdown and markedly reduced by EPRS1 knockdown (Fig. 3B). Knockdown of KARS1 and SARS1 did not reduce ADP-ribosylation showing aaRS specificity. H2O2-treated cells were imaged by immunofluorescence, verifying nuclear localization of EPRS1, confirming reduced ADP-ribosylation in shEPRS1 cells compared to shControl cells (Fig. 3C). The important regulatory role of EPRS1 was verified by over-expression of EPRS1 which increased ADP-ribosylation in MDA-MB-468 cells (Fig. 3D). To assess the requirement for EPRS1 nuclear localization on PARP1 activity, FLAG-tagged WT and 4K>4A mutant EPRS1 were expressed in shEPRS1 cells and ADP-ribosylation determined. Following H2O2 treatment, expression of WT EPRS1 restored ADP-ribosylation to nearly the level in shControl cells; however, expression of the nuclear localization-defective 4K>4A mutant EPRS1 was ineffective, indicating nuclear EPRS1 is required for PARP1 activity (Fig. 3E).

The mechanisms underlying PARP1 activation during the DNA damage response (DDR) remain enigmatic, but include dinucleotide substrate availability, auto-PARylation, protein dimerization, accessory factors, nuclear localization, and reversible chromatin-binding activity (40). We investigated whether EPRS1 regulates the cell level of the PARP1 substrate, NAD+, in MCF-7 cells treated with H2O2 to induce ADP-ribosylation. EPRS1 knockdown reduced both NAD+ and NADH levels, the total dinucleotide level was decreased by ~20%, most likely due to reduced cell proliferation in the knockdown cells (Fig. 4A, first three panels). Nonetheless, the NAD+/NADH ratio was increased by ~30% consistent with diminished NAD+ utilization following EPRS1 knockdown (Fig. 4A, fourth panel). The role of EPRS1 on PARP1 binding to chromatin was investigated. Depletion of EPRS1 did not significantly influence PARP1 in the nucleus-soluble or -insoluble fractions in H2O2-treated MCF-7 cells. (Fig. 4B). Consistent with results in MDA-MB-468 cells (Fig. 1B), chromatin binding was not observed even following H2O2-directed nucleus translocation of EPRS1 in MCF-7 cells. Likewise, EPRS1 binding to chromatin was not observed in MDA-MB-468 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). To determine whether increased PARP1 poly-ADP-ribosylation activity is due to direct activation by EPRS1, purified EPRS1 and His-tagged PARP1 were coincubated, and ADP-ribosylation of immobilized histones, an established PARP1 target, was determined by measuring incorporation of biotinylated PAR. At the maximal level, EPRS1 increased the ADP-ribosylation activity of PARP1 by about 50% (Fig. 4C). The assay was validated by the absence of ADP-ribosylation when PARP1 is inhibited by olaparib. EPRS1 knockdown dramatically reduced PARP1 auto-PARylation as assessed by immunoblot following immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-PARP1 antibody in MDA-MB-468 cells (Fig. 4 D, Left) and in H2O2-treated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4 D, Right). EPRS1 knockdown also inhibited [mono(ADP-ribosylation) (MAR)], i.e., MARylation, of PARP1 at Ser499, confirming its effect on auto-PARylation in both cell types (Fig. 4D) (41). ADP-ribosylation at ~15 kDa was not detected in the input lanes following a prolonged exposure of the ADPr blot, indicating that low-MW histones are not a major ADP-ribosylation target in both cell types (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation of H3 on Ser10 is an important feature of DDR and requires modulation of PARP1 target specificity by interaction with HPF1 (41, 42). MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cells both express HPF1 almost exclusively in the soluble fraction of the nucleus (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), whereas ADP-ribosylated H3S10 is found in both nucleus-soluble- and -insoluble fractions. EPRS1 knockdown caused a small reduction in PARP1-mediated H3S10 mono-ADP-ribosylation consistent with a more substantial role of EPRS1 in poly-ADP-ribosylation in these cells (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of EPRS1-mediated activation of PARP1. (A) Following siRNA-mediated knockdown of EPRS1, MCF-7 cells were incubated with H2O2, and NAD+ (Left) and NADH (2nd panel) were determined by colorimetric assay; total cellular dinucleotide (3rd panel) and their ratio (4th panel) were calculated (mean ± SEM, n = 4). (B) Effect of siEPRS1 knockdown on PARP1 binding to chromatin in the nuclear-insoluble fraction in H2O2-treated MCF-7 cells. Whole-cell lysate and cytoplasm samples were 1% of total; nuclear fractions were 10% of the total. (C) In vitro PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation of immobilized histone in the presence of recombinant EPRS1 was determined by modification by biotinylated PAR; (n = 3, mean ± SEM). (D) PARP1 auto-PARylation was determined in MDA-MB-468 cells (Left) and H2O2-treated MCF-7 cells (Right) by IP with anti-PARP1 antibody followed by immunoblot with anti-ADPr antibody. PARP1 Ser499 MAR was detected by immunoblot. (E) Effect of EPRS1 knockdown on H3S10-ADPr in H2O2-treated MCF-7 cells.

AKT activation is both necessary and sufficient for EPRS1 nuclear translocation and nuclear EPRS1 binds PARP1 and is critical for stress-induced ADP-ribosylation. This sequence of events suggests an important role for AKT in ADP-ribosylation. To address this possibility, MCF-7 cells were incubated with H2O2 in the presence of the AKT inhibitor MK2206, and robust inhibition of ADP-ribosylation was observed (Fig. 5A). To determine whether activated AKT is sufficient for ADP-ribosylation, cells were incubated with the AKT agonist SC79, and activation validated by detection of P-Ser473 AKT (Fig. 5B). SC79 by itself did not induce significant ADP-ribosylation, but it acted synergistically with H2O2. These results indicate that AKT activation is sufficient to induce nuclear translocation of EPRS1 but is not sufficient to induce ADP-ribosylation, and an as-yet unidentified pathway or stress-induced effector is required. A recent report showed EPRS1 Ser999 phosphorylation by AKT in lipopolysaccharide-treated monocytic cells (43). Heat shock–dependent phosphorylation of EPRS1 in MCF-7 cells was not observed by 32P-metabolic labeling or by immunoblot with antibodies against phospho-Ser886 and phospho-Ser999, two major EPRS1 phosphorylation sites (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Thus, the target of AKT contributing to ADP-ribosylation remains unknown.

Fig. 5.

Role of AKT in PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation. (A) Role of AKT in PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation was determined using the AKT inhibitor, MK2206, in H2O2-treated MCF-7 cells. (B) Sufficiency of AKT activation for PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation was shown using the AKT activator, SC79, and ADPr immunoblot was quantitated by densitometry.

EPRS1 Rescues Cells from DNA Damage and Promotes Tumor Sphere Formation.

The effect of EPRS1 on PARP1 functions was investigated. PARP1 bidirectionally influences transcription of multiple gene targets. Knockdown of EPRS1 decreased mRNA expression of known positively regulated PARP1 targets, TMSL8, NELL2, and ITPR1, by about 70 to 75%, comparable to the effect of PARP1 knockdown (44) (Fig. 6A). Likewise, EPRS1 knockdown increases expression of GDF15 mRNA, a negatively regulated PARP1 target. The negative control gene ABHD2 was unaffected by EPRS1 knockdown. Thus, EPRS1 exhibits regulatory activity nearly identical to PARP1, suggesting that it is a critical effector of PARP1 gene regulatory activity.

Fig. 6.

EPRS1 promotes DNA DSB repair and cell survival. (A) Effect of EPRS1 knockdown on mRNA expression of selected PARP1 target genes in shEPRS1 MCF-7 cells treated with H2O2 (n = 3; ns = not significant, t = trend). (B) Alkaline COMET assay assessing DNA DSB formation in shControl, shPARP1, shEPRS1, and shLARS1 MCF-7 cells treated with H2O2 (Left). Quantitative evaluation of tail DNA percentage and tail moment (tail% × tail length) of MCF-7 knockdown cells (Right; mean ± SEM; n = 4). (C) Clonogenic survival assay of shControl, shPARP1, shEPRS1, and shLARS1 in MCF-7 cells treated with MMS for 1 h. (D) Formation of tumor spheres by shControl, shEPRS1, and shPARP1 MCF-7 cells treated with 400 µM H2O2 and then incubated for 14 d (n = 3, mean ± SEM, P < 0.05). (E) MDA-MB-468 cells were subjected to siEPRS1-mediated knockdown and incubated with talazoparib for 72 h. ADPr formation was determined by immunoblot (Left) and quantitated by densitometry (Right); mean ± SEM, n = 3. Talazoparib IC50 was calculated by nonlinear regression of inhibitor concentration versus response (three-parameter fit) using GraphPad. For siCtrl, IC50 = 1.23, R2 = 0.96; for siEPRS1, IC50 = 0.41, R2 = 0.98. IC50’s are illustrated by dashed lines. (F) Effect of EPRS1 knockdown on cell sensitivity to talazoparib was determined by MTT cell survival assay. Rescue of survival by transfection with WT or NLS mutant EPRS1 was determined. For panels C, E, and F: mean ± SEM, n = 3, ns = not significant; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

PARP1 is implicated in the DDR, by recognizing and facilitating the repair of DNA single- and double-strand breaks (DSBs) (37). The influence of EPRS1 on PARP1-mediated DNA repair was explored by alkaline COMET assay to assess DNA DSBs. H2O2 treatment of shPARP1 MCF-7 cells increased tail formation compared to shControl cells, indicative of extensive DNA damage and unrepaired strand breaks (Fig. 6 B, Left). Tail formation was markedly induced in shEPRS1 cells, although to a lesser extent than in PARP1-deficient cells. As a specificity control, tail formation was minimal in shLARS1 cells. DNA damage was quantified as % tail DNA (Fig. 6 B, Right-Top) and tail moment (Fig. 6 B, Right-Bottom). Nuclear EPRS1 reduced DSB formation as shown by rescue of H2O2-treated shEPRS1 knockdown cells with WT, but not NLS mutant, EPRS1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Cell survival following DNA damage was assessed as a functional DNA repair pathway is essential for viability. MCF-7 knockdown cells were incubated with methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), a DNA alkylating agent that causes mutagenesis by base mispairing, and survival was determined by a clonogenic assay. MMS at 200 µM induced ~60% loss of viable cells in shControl and shLARS1 cells (Fig. 6C). shPARP1 and shEPRS1 cells were more susceptible to MMS injury as >95% of cells failed to survive. EPRS1 knockdown likewise increased susceptibility of MDA-MB-468 cells to MMS treatment; knockdown of SARS1 was less effective (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). A hallmark of breast tumor cells and cell lines is their ability to form tumor spheres in vitro. The tumor sphere-forming potential of H2O2-treated shEPRS1 and shPARP1 cells was nearly equally abrogated compared to shControl cells (Fig. 6D). As EPRS1 knockdown increased susceptibility to chemically induced DNA damage, we considered the possibility that EPRS1 knockdown likewise increased susceptibility to the PARP1 inhibitor, talazoparib (BMN 673), a nicotinamide analog that inhibits PARP1 enzymatic activity with a Ki of ~1.2 nM (45). Inhibition of ADP-ribosylation by talazoparib was enhanced by EPRS1 knockdown in MDA-MB-468 cells by about an order-of-magnitude, due in part to a decreased IC50 of talazoparib from 1.23 nM to 0.41 nM (Fig. 6E). Similarly, EPRS1 knockdown increased cell sensitivity to talazoparib by about an order-of-magnitude as shown by MTT cell survival assay (Fig. 6F). Transfection with WT EPRS1, but not the nuclear localization-defective mutant, rescued survival. These results indicate that nuclear EPRS1 knockdown enhances PARP1 inhibitor sensitivity and suggest a therapeutic potential for a combined therapy.

Discussion

Previous reports showed WARS1 and YARS1 bind PARP1 and induce PARP1 activity; thus, our findings on EPRS1 expand the family of aaRSs that exhibit this noncanonical function unrelated to protein synthesis (29, 30, 46). A common feature of the three aaRSs is agonist-dependent nuclear translocation. For all three aaRSs, the domains required for PARP1 activation are not required for tRNA charging, and are appended during eukaryote evolution (47). In WARS1, the N-terminal WHEP domain is critical for nuclear localization, in YARS1, the C-terminal EMAP-II domain is essential, and in EPRS1, the central linker joining the two synthetases is critical. YARS1 and WARS1 are “free” cytoplasmic aaRSs, whereas EPRS1, as an MSC constituent, requires a 2-step pathway involving release from the MSC followed by nuclear localization. Each aaRS/PARP1 interaction exhibits unique features, including agonist and cell-type specificity, auxiliary binding partners, downstream targets, and cellular function. Also differentiating the functional characteristics of these aaRSs, PARP1 activation by WARS1 and YARS1 is dependent on their respective amino acid substrates (29, 30), whereas EPRS1 nuclear localization and PARP1 activation are independent of both glutamate and proline (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). Likewise, halofuginone, a ProRS inhibitor, had only minor effects on H3S10 and total ADPr (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Interferon-γ induces nuclear localization of WARS1 and binding to PARP1 and the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase, activating p53 and inducing apoptosis (30). Resveratrol, a tyrosyl adenylate analog induces nuclear localization of YARS1, binding to PARP1, and p53 activation (29). Here, EPRS1 is localized within the nuclei of PTEN− breast cancer cells and in PTEN+ cells following AKT activation either by heat shock or H2O2. EPRS1 knockdown influenced expression of PARP1-regulated genes, suggesting coordination of EPRS1 and PARP1 to drive an open chromatin structure at target gene promoters for transcription by Pol II (44).

Tumor development is often driven by the inability to repair damaged DNA, driving accumulation of pathological genetic alterations (48–50). DNA single-strand breaks induced in cancer cells, for example, by alkylating agents, are repaired following recognition by PARP1 and subsequent ADP-ribosylation of histones and other repair proteins (51). PARP1 also is critical for repairing DSBs in cancer cells by activating the error-prone, nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, leading to mutations and increased cancer aggressiveness (52). Thus, PARP1 is a target for therapeutic intervention, promising tumor-selective killing, particularly in genetic backgrounds with defective homologous recombination (51). By a synthetic lethal interaction between PARP1 and deficiency in specific cancer susceptibility genes, e.g., BRCA1/2, PARP1 inhibition induces tumor-specific cytotoxicity (49).

AKT activation drives tumorigenesis by promoting tumor cell survival, invasiveness, and proliferation, primarily by inducing a pro-tumorigenic metabolic state following phosphorylation of anabolic enzymes and activation of metabolism-related transcription factors including FOXO, HIF1, and SREBP (53). AKT is activated by engagement with plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-P3 (PIP3), required for kinase-mediated activation. Importantly, PIP3 is subject to bidirectional regulation by the lipid kinase, PI3K, which converts PIP2 to PIP3, and by the lipid phosphatase PTEN, which reverses this reaction, converting PIP3 to PIP2 (53). Thus, PTEN acts as a tumor suppressor and loss of PTEN by mutation or inactivation is associated with severe cancer (14, 15).

AKT and PARP1 both exhibit pro-tumorigenic activities; however, links connecting these critical signaling proteins are unclear. We investigated the role of AKT in ADP-ribosylation in the context of H2O2-activated MCF-7 cells. Inhibition of AKT by MK2206 markedly inhibited ADP-ribosylation. Conversely, activation of AKT by SC79 acted synergistically with H2O2 to induce ADP-ribosylation. These results support previous findings that pharmacological inhibition of AKT acutely inhibits PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation in ovarian cancer cell lines and astrocytes (54, 55). These results suggest a combination therapy targeting both AKT and PARP1 might provide a more effective antitumor strategy (54). Here, we provide evidence for a molecular link between AKT activation and PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation, namely, AKT-mediated nuclear translocation of EPRS1. Our data suggest that EPRS1 is not a direct AKT target since heat shock stress did not induce phosphorylation. A recent report showed EPRS1 was phosphorylated at Ser999 following AKT activation in lipopolysaccharide-treated monocytic cells (43). Multisite phosphorylation of AKT observed might not be achieved in our experimental system but might be necessary for EPRS1 phosphorylation. Thus, the specific function of AKT in stress-induced nuclear translocation of EPRS1 and ADP-ribosylation remains unknown.

The role of EPRS1 in cooperating with PARP1 to maintain genome integrity was considered. The influence of EPRS1 on expression of PARP1-regulated genes was examined. EPRS1 knockdown precisely reproduced the influence of PARP1 as described (44). Namely, EPRS1 knockdown reduced expression of PARP1 targets, TMSL8, NELL2, and ITPR1, and stimulated expression of GDF15. Notably, DNA damage can induce GDF15 (56), and patients with elevated GDF15 have a 4.8-fold increased risk of cancer death (57). A possible pathway by which EPRS1 stimulates PARP1-mediated DNA repair is shown in Fig. 7. We show that EPRS1 stimulates PARP1-mediated auto-PARylation, but also to a lesser extent, the ADP-ribosylation of histones. Increased PARP1 activity enhances chromatin relaxation and remodeling, facilitating repair by enhanced protein binding (58). Alternatively, a moderate level of auto-PARylation alters the mobility of DNA-bound PARP1 circumscribing a DNA lesion, reducing steric interference for subsequent binding of repair proteins (59). Our observation that EPRS1 alters talazoparib IC50 is consistent with a conformational alteration of PARP1 that might also alter the interaction with target proteins. The coelution of EPRS1 and PARP1 in fractions with MW ~700 kDa, a size greater than the combined MW of ~300 kDa, suggests that other proteins might be in the complex, or possibly the complex contains dimers of both proteins (Fig. 7). EPRS1 dimerizes through ProRS domain interactions (3, 60) and chromatin-bound PARP1 dimers have been observed (61).

Fig. 7.

Schematic of enhanced PARP1-mediated DNA repair by EPRS1.

PARP1 is critical for repairing DSBs in cancer cells by activating the NHEJ pathway, which is error-prone and associated with increased cancer aggressiveness (52). EPRS1 knockdown increased DSBs as shown by increased tail formation in a COMET assay. Furthermore, knockdown of EPRS1 and PARP1 reduced cell survival and tumor sphere formation to comparable extents. PARP1 inhibition has shown promise in treatment of PTEN-negative breast cancers, particularly in patients with mutations in the BRCA breast cancer susceptibility genes (62). Talazoparib is a potent PARP1 inhibitor approved for combination therapy of advanced breast cancer and metastatic prostate cancer. We show that EPRS1 knockdown synergizes with talazoparib to decrease ADP-ribosylation. EPRS1 knockdown decreases the IC50 of talazoparib from 1.23 nM to 0.41 nM. Possibly, EPRS1 binding alters PARP1 conformation to facilitate talazoparib occupying the binding pocket that extends beyond the pocket of the NAD+ substrate (63). Our finding that talazoparib inhibits ADP-ribosylation at a ~10-fold lower concentration of the inhibitor following EPRS1 knockdown suggests a therapeutic potential for the combined therapy. Thus, targeting the noncanonical PARP1-binding activity of EPRS1, without inhibiting canonical tRNA ligase activity, might provide an imporved therapeutic approach supplementing PARP1 inhibitors.

Material and Methods

Cells and Reagents.

Cell lines, plasmid constructs, antibodies, kits, RNAs, and other reagents are described in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

In Vivo ADP-Ribosylation Assay.

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cells were transiently transfected with constructs using lentiviral particles or pcDNA over-expression constructs. To induce DNA damage, the cells were treated with 400 µM H2O2 in serum-containing medium for 10 min. The cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and the reaction stopped with 2× Laemmli SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 0.1 M EDTA. ADP-ribosylation was assessed by immunoblot with anti-ADPr antibody.

PARP1 Activity Assay.

For PARP1-mediated in vitro poly-ADP-ribosylation assay, samples, containing 0.2 µg of recombinant human PARP1, and 1 to 5 µg of recombinant HEK293-derived FLAG-EPRS1, were incubated in 50 µL of PARP reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM TCEP) for 30 min. PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation of immobilized histone proteins was determined by modification using biotinylated PAR and determined by HT Universal 96-well PARP Assay Kit.

Data and Statistical Analysis.

All experiments were performed in triplicate unless otherwise indicated. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were done by Student’s t tests using GraphPad Prism 7.0. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant; a P-value of <0.1 was considered a trend (t). Inhibitor IC50 was calculated by nonlinear regression of inhibitor concentration versus response (three-parameter fit) using GraphPad Prism 7.0. Brightness and contrast in some images were adjusted to improve clarity without changing relative intensity levels in the images; all images in the same condition were modified identically.

Other Methods.

Standard methods including cloning and generation of cDNA constructs, recombinant EPRS1 expression and purification, lentivirus production and siRNA- and shRNA-mediated gene knockdown, subcellular fractionation, coimmunoprecipitation, mass spectrometry and proteomic analysis, cell treatments, western blot analysis, confocal microscopy and immunocytochemistry, alkaline comet assay, clonogenic cell survival assay, tumor sphere assay, NAD assay, MTT assay, and size-exclusion chromatography are described in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK124203, R01 DK123236 to P.L.F.); National Institute on Aging (R01 AG067146 to P.L.F.); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS124547 to V.G. and P.L.F., R01 NS124581 to P.L.F.); Research Accelerator Program Grant from the Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic (to P.L.F.); and VelaSano 6 Pilot Award (to P.L.F.).

Author contributions

I.Z., A.C., K.K., J.K.N., K.V., D.K., I.R., V.G., and P.L.F. designed research; I.Z., A.C., K.K., J.K.N., K.V., G.M.D., P.K.G., D.K., I.R., S.G., and I.T. performed research; I.Z., A.C., K.K., J.K.N., K.V., G.M.D., P.K.G., D.K., I.R., S.G., I.T., B.W., V.G., and P.L.F. analyzed data; and I.Z., A.C., K.V., B.W., and P.L.F. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Eswarappa S. M., Potdar A. A., Sahoo S., Sankar S., Fox P. L., Metabolic origin of the fused aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 19148–19156 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampath P., et al. , Noncanonical function of glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase: Gene-specific silencing of translation. Cell 119, 195–208 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan K., Baleanu-Gogonea C., Willard B., Gogonea V., Fox P. L., 3-Dimensional architecture of the human multi-tRNA synthetase complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8740–8754 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray P. S., et al. , A stress-responsive RNA switch regulates VEGFA expression. Nature 457, 915–919 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arif A., et al. , EPRS is a critical mTORC1-S6K1 effector that influences adiposity in mice. Nature 542, 357–361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee E. Y., et al. , Infection-specific phosphorylation of glutamyl-prolyl tRNA synthetase induces antiviral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 17, 1252–1262 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan D., et al. , A viral pan-end RNA element and host complex define a SARS-CoV-2 regulon. Nat. Commun. 14, 3385 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendes M. I., et al. , Bi-allelic mutations in EPRS, encoding the glutamyl-prolyl-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, cause a hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 676–684 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawaguchi S., et al. , Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 15 (HLD15)-associated mutation of EPRS1 leads to its polymeric aggregation in Rab7-positive vesicle structures, inhibiting oligodendroglial cell morphological differentiation. Polymers (Basel) 13, 1074 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Line A., et al. , Characterisation of tumour-associated antigens in colon cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 51, 574–582 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsyv I., et al. , EPRS is a critical regulator of cell proliferation and estrogen signaling in ER+ breast cancer. Oncotarget 7, 69592–69605 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beltran A. S., Graves L. M., Blancafort P., Novel role of Engrailed 1 as a prosurvival transcription factor in basal-like breast cancer and engineering of interference peptides block its oncogenic function. Oncogene 33, 4767–4777 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H., et al. , EPRS/GluRS promotes gastric cancer development via WNT/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway. Gastric Cancer 24, 1021–1036 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgescu M. M., PTEN tumor suppressor network in PI3K-Akt pathway control. Genes Cancer 1, 1170–1177 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carracedo A., Pandolfi P. P., The PTEN-PI3K pathway: Of feedbacks and cross-talks. Oncogene 27, 5527–5541 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papa A., Pandolfi P. P., The PTEN-PI3K axis in cancer. Biomolecules 9, 153 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tserga A., Chatziandreou I., Michalopoulos N. V., Patsouris E., Saetta A. A., Mutation of genes of the PI3K/AKT pathway in breast cancer supports their potential importance as biomarker for breast cancer aggressiveness. Virchows Arch. 469, 35–43 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe C. L., Warrington J. A., Davis S., Green S., Norcum M. T., Isolation and characterization of human nuclear and cytosolic multisynthetase complexes and the intracellular distribution of p43/EMAPII. Protein Sci. 12, 2282–2290 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathanson L., Deutscher M. P., Active aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are present in nuclei as a high molecular weight multienzyme complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31559–31562 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cahuzac B., Berthonneau E., Birlirakis N., Guittet E., Mirande M., A recurrent RNA-binding domain is appended to eukaryotic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. EMBO J. 19, 445–452 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia J., Arif A., Ray P. S., Fox P. L., WHEP domains direct noncanonical function of glutamyl-prolyl tRNA synthetase in translational control of gene expression. Mol. Cell 29, 679–690 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mo L., et al. , PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-induced heme oxygenase-1 upregulation mediates the adaptive cytoprotection of hydrogen peroxide preconditioning against oxidative injury in PC12 cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 30, 314–320 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bang O. S., Ha B. G., Park E. K., Kang S. S., Activation of Akt is induced by heat shock and involved in suppression of heat-shock-induced apoptosis of NIH3T3 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 306–311 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadidi M., Lentz S. I., Feldman E. L., Hydrogen peroxide-induced Akt phosphorylation regulates Bax activation. Biochimie 91, 577–585 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carmi-Levy I., et al. , Importin beta plays an essential role in the regulation of the LysRS-Ap(4)A pathway in immunologically activated mast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 2111–2121 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duchon A. A., et al. , HIV-1 exploits a dynamic multi-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex to enhance viral replication. J. Virol. 91, e01240-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko Y. G., Kang Y. S., Kim E. K., Park S. G., Kim S., Nucleolar localization of human methionyl-tRNA synthetase and its role in ribosomal RNA synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 149, 567–574 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Y., et al. , tRNA synthetase counteracts c-Myc to develop functional vasculature. Elife 3, e02349 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sajish M., Schimmel P., A human tRNA synthetase is a potent PARP1-activating effector target for resveratrol. Nature 519, 370–373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sajish M., et al. , Trp-tRNA synthetase bridges DNA-PKcs to PARP-1 to link IFN-gamma and p53 signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 547–554 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jo H., et al. , Small molecule-induced cytosolic activation of protein kinase Akt rescues ischemia-elicited neuronal death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 10581–10586 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma N., et al. , Mechanisms for increased insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake in fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscles of calorie-restricted rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 300, E966–978 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z. Y., et al. , The prognostic value of phosphorylated Akt in breast cancer: A systematic review. Sci. Rep. 5, 7758 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glynn S. A., et al. , COX-2 activation is associated with Akt phosphorylation and poor survival in ER-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer. BMC Cancer 10, 626 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slade D., PARP and PARG inhibitors in cancer treatment. Genes Dev. 34, 360–394 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mateo J., et al. , A decade of clinical development of PARP inhibitors in perspective. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1437–1447 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ray Chaudhuri A., Nussenzweig A., The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 610–621 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rank L., et al. , Analyzing structure-function relationships of artificial and cancer-associated PARP1 variants by reconstituting TALEN-generated HeLa PARP1 knock-out cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 10386–10405 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakondi E., et al. , Detection of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in oxidatively stressed cells and tissues using biotinylated NAD substrate. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50, 91–98 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamaletdinova T., Fanaei-Kahrani Z., Wang Z. Q., The enigmatic function of PARP1: From PARylation activity to PAR readers. Cells 8, 1625 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonfiglio J. J., et al. , An HPF1/PARP1-based chemical biology strategy for exploring ADP-rribosylation. Cell 183, 1086–1102.e23 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longarini E. J., et al. , Modular antibodies reveal DNA damage-induced mono-ADP-ribosylation as a second wave of PARP1 signaling. Mol. Cell 83, 1743–1760.e11 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee E. Y., et al. , Glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase 1 coordinates early endosomal anti-inflammatory AKT signaling. Nat. Commun. 13, 6455 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnakumar R., Kraus W. L., PARP-1 regulates chromatin structure and transcription through a KDM5B-dependent pathway. Mol. Cell 39, 736–749 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang B., et al. , Discovery and characterization of (8S,9R)-5-Fluoro-8-(4-fluorophenyl)-9-(1-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)-2,7,8,9-tetrahydro-3H-pyrido[4,3,2-de]phthalazin-3-one (BMN 673, Talazoparib), a novel, highly potent, and orally efficacious poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1/2 Inhibitor, as an anticancer agent. J. Med. Chem. 59, 335–357 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jhanji M., Rao C. N., Sajish M., Towards resolving the enigma of the dichotomy of resveratrol: Cis- and trans-resveratrol have opposite effects on TyrRS-regulated PARP1 activation. Geroscience 43, 1171–1200 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo M., Schimmel P., Essential nontranslational functions of tRNA synthetases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 145–153 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H. T., et al. , The role of TAp63gamma and P53 point mutations in regulating DNA repair, mutational susceptibility and invasion of bladder cancer cells. Elife 10, e71184 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dietlein F., Thelen L., Reinhardt H. C., Cancer-specific defects in DNA repair pathways as targets for personalized therapeutic approaches. Trends Genet. 30, 326–339 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang R., Zhou P. K., DNA damage repair: Historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 254 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ali A. A. E., et al. , The zinc-finger domains of PARP1 cooperate to recognize DNA strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 685–692 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banerjee R., et al. , TRIP13 promotes error-prone nonhomologous end joining and induces chemoresistance in head and neck cancer. Nat. Commun. 5, 4527 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoxhaj G., Manning B. D., The PI3K-AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 74–88 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu J., et al. , An effective AKT inhibitor-PARP inhibitor combination therapy for recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 89, 683–695 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J. E., Kang T. C., PKC, AKT and ERK1/2-mediated modulations of PARP1, NF-kappaB and PEA15 activities distinctly regulate regional specific astroglial responses following status epilepticus. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12, 180 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shang J., et al. , An integrated preprocessing approach for exploring single-cell gene expression in rare cells. Sci. Rep. 9, 19758 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Negishi K., Hoshide S., Shimpo M., Kario K., Growth differentiation factor 15 predicts cancer death in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: The J-HOP study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 660317 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luijsterburg M. S., et al. , DDB2 promotes chromatin decondensation at UV-induced DNA damage. J. Cell Biol. 197, 267–281 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu L., et al. , PARP1 changes from three-dimensional DNA damage searching to one-dimensional diffusion after auto-PARylation or in the presence of APE1. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 12834–12847 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yaremchuk A., Cusack S., Tukalo M., Crystal structure of a eukaryote/archaeon-like protyl-tRNA synthetase and its complex with tRNAPro(CGG). EMBO J. 19, 4745–4758 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langelier M. F., Ruhl D. D., Planck J. L., Kraus W. L., Pascal J. M., The Zn3 domain of human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) functions in both DNA-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) synthesis activity and chromatin compaction. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18877–18887 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mendes-Pereira A. M., et al. , Synthetic lethal targeting of PTEN mutant cells with PARP inhibitors. EMBO Mol. Med. 1, 315–322 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aoyagi-Scharber M., et al. , Structural basis for the inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases 1 and 2 by BMN 673, a potent inhibitor derived from dihydropyridophthalazinone. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 70, 1143–1149 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.