Abstract

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD), or depression, is a syndrome characterised by a number of behavioural, cognitive and emotional features. It is most commonly associated with a sad or depressed mood, a reduced capacity to feel pleasure, feelings of hopelessness, loss of energy, altered sleep patterns, weight fluctuations, difficulty in concentrating and suicidal ideation. There is a need for more effective and better tolerated antidepressants to combat this condition. Agomelatine was recently added to the list of available antidepressant drugs; it is a novel antidepressant that works on melatonergic (MT1 and MT2), 5‐HT 2B and 5‐HT2C receptors. Because the mechanism of action is claimed to be novel, it may provide a useful, alternative pharmacological strategy to existing antidepressant drugs.

Objectives

The objective of this review was 1) to determine the efficacy of agomelatine in alleviating acute symptoms of major depressive disorder in comparison with other antidepressants, 2) to review the acceptability of agomelatine in comparison with other antidepressant drugs, and, 3) to investigate the adverse effects of agomelatine, including the general prevalence of side effects in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Collaboration's Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR) to 31 July 2013. The CCDANCTR includes relevant randomised controlled trials from the following bibliographic databases: CENTRAL (the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) (all years), EMBASE (1974 onwards), MEDLINE (1950 onwards) and PsycINFO (1967 onwards). We checked reference lists of relevant studies together with reviews and regulatory agency reports. No restrictions on date, language or publication status were applied to the search. Servier Laboratories (developers of agomelatine) and other experts in the field were contacted for supplemental data.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials allocating adult participants with major depression to agomelatine versus any other antidepressive agent.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and a double‐entry procedure was employed. Information extracted included study characteristics, participant characteristics, intervention details and outcome measures in terms of efficacy, acceptability and tolerability.

Main results

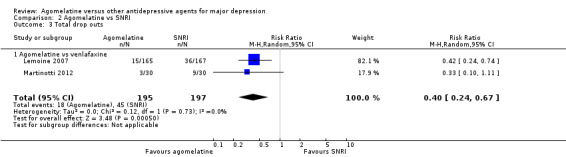

A total of 13 studies (4495 participants) were included in this review. Agomelatine was compared to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), namely paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, and to the serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), venlafaxine. Participants were followed up for six to 12 weeks. Agomelatine did not show any advantage or disadvantage over the other antidepressants for our primary outcome, response to treatment (risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.95 to 1.08, P value 0.75 compared to SSRIs, and RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.16, P value 0.16 compared to venlafaxine). Also, agomelatine showed no advantage or disadvantage over other antidepressants for remission (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.01, P value 0.07 compared to SSRIs, and RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.24, P value 0.73 compared to venlafaxine). Overall, agomelatine appeared to be better tolerated than venlafaxine in terms of lower rates of drop outs (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.67, P value 0.0005), and showed the same level of tolerability as SSRIs (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.09, P value 0.44). Agomelatine induced a lower rate of dizziness than venlafaxine (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.64, P value 0.007).

With regard to the quality of the body of evidence, there was a moderate risk of bias for all outcomes, due to the number of included unpublished studies. There was some heterogeneity, particularly between published and unpublished studies. The included studies were conducted in inpatient and outpatient settings, thus limiting the generalisability of the results to primary care settings. With regard to precision, the efficacy outcomes were precise, but the tolerability outcomes were mostly imprecise. Publication bias was variable and depended on the outcome of the trial. Our review included unpublished studies, and we think that this reduced the impact of publication bias. The overall methodological quality of the studies was not very good. Almost all of the studies were sponsored by the pharmaceutical company that manufactures agomelatine (Servier), and some of these were unpublished. Attempts to contact the pharmaceutical company Servier for additional information on all unpublished studies were unsuccessful.

Authors' conclusions

Agomelatine did not seem to provide a significant advantage in efficacy over other antidepressive agents for the acute‐phase treatment of major depression. Agomelatine was better tolerated than paroxetine and venlafaxine in terms of overall side effects, and fewer participants treated with agomelatine dropped out of the trials due to side effects compared to sertraline and venlafaxine, but data were limited because the number of included studies was small. We found evidence that compared agomelatine with only a small number of other active antidepressive agents, and there were only a few trials for each comparison, which limits the generalisability of the results. Moreover, the overall methodological quality of the studies was low, and, therefore, no firm conclusions can be drawn concerning the efficacy and tolerability of agomelatine.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Acetamides; Acetamides/adverse effects; Acetamides/therapeutic use; Antidepressive Agents; Antidepressive Agents/adverse effects; Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use; Depressive Disorder, Major; Depressive Disorder, Major/drug therapy; Melatonin; Melatonin/agonists; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors/adverse effects; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Agomelatine versus other antidepressant medication for depression

Why is this review important?

Major depression is a serious illness that can cause significant distress both to sufferers and their families. Major depression affects people's work, relationships and self‐esteem. It also affects people physically, changing their sleep patterns, concentration and appetite. The symptoms of major depression can lead people to feel hopeless and even suicidal. Antidepressant medications are an effective treatment option for major depression, but many have unpleasant side‐effects.

This review is important because it compares a new antidepressant, called agomelatine, with some other antidepressants used to treat major depression. Agomelatine works in a different way to existing antidepressants, it affects the hormone melatonin in the brain, and stimulates release of the brain chemicals dopamine and norepinephrine.

Who may be interested in this review?

People affected by major depression.

General Practitioners (GPs), psychiatrists and pharmacists.

Professionals working in adult mental health services.

Families and friends of people who suffer from major depression.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

Does agomelatine work better than other antidepressant medications?

Do patients tolerate agomelatine better than other antidepressants?

How do the side‐effects of agomelatine compare with other antidepressants?

Which studies were included in the review?

In July 2013, we used electronic medical databases to find all published and unpublished medical trials that compared agomelatine with any other antidepressant. We also contacted Servier Laboratories (the developers of agomelatine) for additional information. To be included in the review, medical trials had to have a randomised design (i.e. be randomised controlled trials), and have adult participants (aged over 18) with a diagnosis of major depression.

We identified 13 medical trials, involving a total of 4495 participants, that could be included in the review. The reviewers rated the overall quality of the trials as 'moderate'. Almost all of the trials included were sponsored by the pharmaceutical company that developed agomelatine (Servier), which could introduce bias (research shows that funding strongly affects the outcomes of research studies).

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

The review included trials comparing agomelatine with a group of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and one antidepressant from the serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor group, called venlafaxine. Participants in the studies were followed up for between six to 12 weeks.

‐ Agomelatine was no more or less effective in reducing symptoms of depression than any of the other antidepressants.

‐ Agomelatine was no more or less effective in preventing relapse of depression than any of the other antidepressants.

‐ Agomelatine was tolerated better than venlafaxine (fewer people discontinued treatment), but the same as the SSRIs.

‐ Agomelatine caused a lower rate of dizziness than venlafaxine.

‐ Agomelatine caused a lower rate of vomiting, nausea and sexual side‐effects than SSRIs.

What should happen next?

The reviewers conclude that agomelatine is not more effective than other antidepressants currently on the market. It did seem to be more tolerable to patients in terms of lower rates of some side‐effects, however, the quality of trials was low and there were only a few trials that compared agomelatine with each medication. No firm conclusion on agomelatine can be made because of problems with reporting of data in the trials included. The authors recommend that further trials of agomelatine versus placebo (dummy pill), particularly in primary care settings (where the majority of patient/practitioner contact take place, e.g. GP surgeries), should be carried out to improve the quality of evidence.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Agomelatine compared to SSRI for major depression.

| Agomelatine compared to SSRI for major depression | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with major depression Settings: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: agomelatine Comparison: SSRI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SSRI | Agomelatine | |||||

| Response rates Number of participants showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for Depression, the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale or any other depression scale Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) | 3826 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 610 per 1000 | 616 per 1000 (579 to 658) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 557 per 1000 | 563 per 1000 (529 to 602) | |||||

| Remission rates The number of participants who achieved remission as defined by: a score of 7 or less on the 17‐item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; 10 or less on the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale; 'not ill or borderline mentally ill' on the Clinical Global Impression ‐ Severity; or any other equivalent value on a depression scale defined by the authors Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 3826 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Most of the difference in heterogeneity existed between published and unpublished studies | |

| 363 per 1000 | 302 per 1000 (247 to 367) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 264 per 1000 | 219 per 1000 (180 to 267) | |||||

| Total drop outs Total number of participants who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) | 3826 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 189 per 1000 | 180 per 1000 (157 to 206) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 188 per 1000 | 179 per 1000 (156 to 205) | |||||

| Drop out due to inefficacy Number of participants who dropped out due to inefficacy during the trial, as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.71 to 1.37) | 3377 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 44 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (31 to 60) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 49 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (35 to 67) | |||||

| Drop outs due to side effects Number of participants who dropped out due to side effects during the trial, as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.68 (0.51 to 0.91) | 3377 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 70 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (35 to 63) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 65 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (33 to 59) | |||||

| Total number of participants with side effects Total number of participants experiencing at least one side effect Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.84 to 0.98) | 2490 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 594 per 1000 | 540 per 1000 (499 to 582) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 611 per 1000 | 556 per 1000 (513 to 599) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Most studies were funded by the pharmaceutical company that manufactures agomelatine (Servier). Four out of ten studies were unpublished 2 The studies included in our review were conducted in inpatient and outpatient settings. Results may not be generalisable for a primary care setting 3 Heterogeneity is very high

Summary of findings 2. Agomelatine compared to SNRI for major depression.

| Agomelatine compared to SNRI for major depression | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with major depression Settings: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: agomelatine Comparison: SNRI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SNRI | Agomelatine | |||||

| Response rates Number of participants showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for Depression, the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale or any other depression scale Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.06 (0.98 to 1.16) | 669 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 727 per 1000 | 771 per 1000 (712 to 843) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 707 per 1000 | 749 per 1000 (693 to 820) | |||||

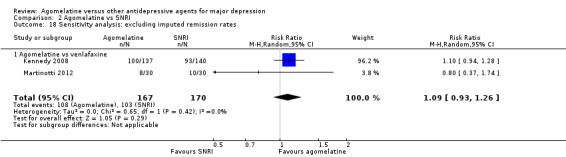

| Remission rates The number of participants who achieved remission as defined by: a score of 7 or less on the 17‐item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; 10 or less on the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale; 'not ill or borderline mentally ill' on the Clinical Global Impression ‐ Severity; or any other equivalent value on a depression scale defined by the authors Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) | 669 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 454 per 1000 | 490 per 1000 (427 to 563) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 333 per 1000 | 360 per 1000 (313 to 413) | |||||

| Total drop outs Total number of participants who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants Follow‐up: 6 to 8 weeks | Study population | RR 0.4 (0.24 to 0.67) | 392 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 228 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (55 to 153) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 258 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (62 to 173) | |||||

| Drop out due to inefficacy Number of participants who dropped out due to inefficacy during the trial, as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants Follow‐up: 6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.21 to 4.94) | 332 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 18 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (4 to 89) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 18 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (4 to 89) | |||||

| Drop outs due to side effects Number of participants who dropped out due to side effects during the trial, as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants Follow‐up: 6 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.3 (0.15 to 0.59) | 608 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 111 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (17 to 66) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 109 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (16 to 64) | |||||

| Total number of patients with side effects Total number of participants experiencing at least one side effect | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.44 to 1.18) | 611 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 481 per 1000 | 346 per 1000 (211 to 567) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 471 per 1000 | 339 per 1000 (207 to 556) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 The studies included in our review were conducted in inpatient and outpatient settings. Results may not be generalisable for a primary care setting 2 Most studies were funded by the pharmaceutical company that manufactures agomelatine (Servier) 3 There is high heterogeneity

Background

Description of the condition

Major depressive disorder (MDD), or depression, is a syndrome characterised by a number of behavioural, cognitive and emotional features. It is most commonly associated with a sad or depressed mood, a reduced capacity to feel pleasure, hopelessness, loss of energy, altered sleep patterns, weight fluctuations, difficulty in concentrating and suicidal ideation (APA 2000). MDD is among the most common medical illnesses. The National Co‐morbidity Survey Replication estimated the lifetime prevalence of MDD to be 16.2% and the 12‐month prevalence to be 6.6%, with a mean depressive episode duration of 16 weeks (Kessler 2003). Women were 1.7 times more likely than men to have MDD (Kessler 2003). MDD is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity; loss of functioning and productivity; and creates significant demands on service providers in terms of workload (NICE 2004). It is the third leading cause of burden from disease and accounts for 4.5% of all human disability (WHO 2008). Additionally, MDD is expected to show a rising trend in the next 20 years (WHO 2008).

Description of the intervention

The treatment of depression includes both psychological (most commonly cognitive behavioural and interpersonal therapies) and pharmacological therapies. With the arrival of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the 1980s, and subsequent new antidepressant drugs, the use of antidepressants to treat depression has increased greatly (Middleton 2001). SSRIs have been recommended for first‐line drug use in depression by most of the treatment guidelines (APA 2000a; Lam 2009; NICE 2004; Taylor 2009), largely because of having a better safety profile, rather than superior efficacy. SSRIs are not without problems. Their effect size has been found to be small in comparison to placebo, in mild to moderate depression (Fournier 2010). Moreover, in clinical trials, SSRIs are associated with sexual dysfunction in 30% to 70% of participants (Clayton 2006). SSRIs also cause difficulties in sleep and agitation (Dording 2002). Therefore, the search is on for better antidepressant drugs. The ideal medication for depression would be a drug with a high level of effectiveness and a favourable side‐effect profile. Until now there has been little evidence to support one antidepressant over another. A number of previous meta‐analyses have concluded that there are no significant differences in either efficacy or acceptability between the various second‐generation antidepressants currently on the market (AHRQ 2007; Hansen 2005), although a recent multiple treatment meta‐analysis of 12 new‐generation antidepressant drugs, which used both direct and indirect data, reported the possible superiority of sertraline and escitalopram in terms of efficacy and acceptability (Cipriani 2009).

Agomelatine was recently added to the list of available antidepressant drugs; it works on melatonergic (MT1 and MT2), 5‐HT2B and 5‐HT2C receptors. Since its mechanism of action is claimed to be novel, it may provide a useful alternative pharmacological strategy to existing antidepressant drugs. Its positive effect on the sleep‐wake cycle and lack of serious side effects, including sexual side effects, may provide added advantages (Dolder 2008). Agomelatine has been licensed in the EU for the treatment of depression since 2009 (EMEA 2009). Novartis discontinued the development of agomelatine for the US market in 2011 (Novartis 2012).

How the intervention might work

Agomelatine is a new antidepressant drug with a unique mechanism of action. It acts as an agonist on melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors, and an antagonist on 5‐HT2B and 5‐HT2C receptors. The MT1 receptor directly inhibits firing of the neurons in the suprachiasmatic areas in the hypothalamus, regulating the amplitude of circadian rhythmicity, whilst the MT2 receptor is responsible for the entrainment of circadian rhythms (San 2008). Antagonism at 5‐HT2C receptor causes a postulated increase in frontal dopamine transmission in animal models (Millan 2003). Agomelatine has shown some antidepressant‐like activity in animal models of depression (Popoli 2009). It has been studied for major depression in adults at doses of 25 mg to 50 mg/day given in the evenings (Popoli 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

Agomelatine is a unique antidepressant drug that has been found to be effective when compared with placebo and other antidepressant drugs (Kasper 2008). Its efficacy and tolerability compared to other antidepressants have been assessed in a recent meta‐analyses of published trials (Singh 2011), and a pooled analysis of selected trials (Kasper 2013). Another systematic review of placebo controlled trials (Koesters 2013), questioned whether there is a clinically important difference between agomelatine and placebo. However, as shown by Howland 2011 and Koesters 2013, published evidence for agomelatine may be influenced by publication bias. Therefore, there is good reason to conduct a systematic quantitative review using both published and unpublished evidence for its comparative efficacy, and adverse effects, against other antidepressant drugs.

Objectives

The objective of this review was 1) to determine the efficacy of agomelatine in alleviating acute symptoms of major depressive disorder in comparison with other antidepressants, 2) to review the acceptability of agomelatine in comparison with other antidepressant drugs, and, 3) to investigate the adverse effects of agomelatine, including the general prevalence of side effects in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials using a parallel group design that compared agomelatine with other antidepressant agents as monotherapies. For cross‐over trials we included only the results from the first randomised period.

Types of participants

Participants of both sexes, aged 18 years or older, with a primary diagnosis of major depression.

We included studies that used any standardised criteria to define unipolar major depression. We expected that most studies would use DSM‐IV (APA 1994), DSM‐ IV‐TR (APA 2000), or ICD‐10 (WHO 1992). Older studies might have used ICD‐9 (WHO 1978), DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐ III‐R (APA 1987), or other diagnostic systems. We excluded studies that used ICD‐9 because it does not have operationalised criteria, but only disease names and no diagnostic criteria. However, we included studies that used Feighner criteria (Feighner 1972), or Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978).

We included studies in which less than 20% of participants were suffering from bipolar depression, but we examined the validity of the decision in a sensitivity analysis.

We did not consider a concurrent secondary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder as a criterion for exclusion, though we did consider a concurrent primary diagnosis of Axis I or II disorders as an exclusion criterion. We excluded participants with a concurrent DSM‐IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, or a psychosis not otherwise specified. We excluded antidepressant trials in depressive participants with a serious concomitant medical illness.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Agomelatine

Comparator interventions

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, paroxetine, escitalopram)

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran)

Other antidepressive agents (tricyclic or heterocyclic antidepressants; monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs); newer agents (mirtazapine, bupropion, reboxetine); atypical antipsychotics in monotherapy (risperidone, paliperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole, amisulpride, ziprasidone); non‐conventional (herbal products such as Hypericum).

In future updates, if studies become available, we will group the other antidepressants according to classes in further comparisons.

We applied no restrictions regarding dose, frequency, intensity or duration.

We excluded trials in which agomelatine was used as an augmentation strategy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome measure for efficacy was:

the number of participants who responded to treatment, showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM‐D) (Hamilton 1960), the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979), or any other depression scale (e.g. the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1987), or the CES‐D scale (Radloff 1977)); or were 'much or very much improved' (score 1 or 2) on the Clinical Global Impression‐Improvement (CGI‐I) (Guy 1976).

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcome measures included:

the number of participants who achieved remission as defined by: a score of 7 or less on the 17‐item HAM‐D, or 8 or less on the longer version of HAM‐D; 10 or less on the MADRS; 'not ill or borderline mentally ill' on the CGI‐S (Guy 1976); or any other equivalent value on a depression scale defined by the authors. We preferred remission rates defined by the HAM‐D or MADRS scores.

group mean scores at endpoint on HAM‐D, MADRS, CGI‐S or any other depression rating scale score.

Acceptability was evaluated using the following outcome measures:

total drop‐out rate: i.e. total number of participants who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants.

drop‐out rates due to inefficacy: i.e. number of participants who dropped out due to inefficacy during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants.

drop‐out rates due to side effects: i.e. number of participants who dropped out due to side effects during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants.

Tolerability was evaluated using the following outcome measures:

total number of participants experiencing at least some side effects.

-

total number of participants experiencing the following specific side effects:

sleepiness or drowsiness;

insomnia;

dry mouth;

constipation;

dizziness;

hypotension;

agitation or anxiety;

suicide wishes, gestures or attempts;

completed suicide;

vomiting or nausea;

diarrhoea;

sexual dysfunction;

abnormal liver function tests;

weight gain;

hypertension.

In order not to miss any relatively rare or unexpected yet important side effects, in the data extraction phase we collected all side‐effect data reported in the literature and discussed ways to summarize them later.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintains two clinical trials registers at the editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 31,500 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 65% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, using a controlled vocabulary (please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator for further details). Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 onwards), EMBASE (1974 onwards) and PsycINFO (1967 onwards); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organization's (WHO) trials portal (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)), pharmaceutical companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website.

Electronic searches

The CCDANCTR‐Studies Register was searched using the following terms: Diagnosis = depress* and Intervention = agomelatine and Age group = (adult or aged or unclear or "not stated")

The CCDANCTR‐References Register was searched using free‐text terms to identify additional untagged/uncoded reports of RCTs: (depress* and agomelatine)

International trial registers were searched via the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), which includes access to Controlled‐Trials.com where Servier Laboratories (developers of agomelatine) register their trial protocols. The following search terms were used: (agomelatine or valdoxan or thymanax)

The literature search was last updated on 31 July 2013.

Searching other resources

Personal communication

We contacted experts in the field for information on unpublished or ongoing studies, or to request additional trial data. We contacted Servier Laboratories directly in Slough (UK) and Paris (France), but they failed to respond to our request for additional data.

Reference checking

We checked the reference lists of all included studies, relevant reviews and regulatory agency reports to identify additional studies missed from the original electronic searches, and also conducted a cited reference search on the Web of Science.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection of trials for inclusion in this systematic review was done by two of the review authors.

Both review authors inspected the search hits by reading the titles and the abstracts to see if they met the inclusion criteria. Possible doubts were resolved by consultation with each other. We obtained each potentially relevant study located in the search as a full article, then two review authors independently assessed each for inclusion, and, if there was disagreement sought resolution through discussion between review authors. The discordance in the selection of studies was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa (k) (Cohen 1960), a more robust measure than a simple per cent agreement calculation since it takes into account the agreement between review authors that occurs by chance. Where it was not possible to evaluate the study because of language problems or missing information, we have classified the study as a 'study awaiting classification' until we can obtain either a translation or further information. We have reported the reasons for exclusion of trials in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently used a data extraction form to extract the data from included studies concerning participant characteristics (age, sex, severity of depression, study setting), intervention details (dosage, duration of study, sponsorship), study characteristics (blinding, allocation etc.) and outcome measures of interest. Again, any disagreement was resolved by consensus or by the third member of the review team. If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain clarification.

Main comparisons

Agomelatine versus SSRIs

Agomelatine versus SNRIs

Agomelatine versus other antidepressive agents (see Types of interventions)

Where sufficient data were available, we presented the results grouped by substance as well.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, two authors assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome assessment, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We also considered sponsorship bias.

The risk of bias, in each domain and overall, was assessed and categorised as either:

low risk of bias, i.e. plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results; or

high risk of bias, i.e. plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results; or

unclear risk of bias, i.e. plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results.

If the assessors disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus or with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where insufficient details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We agreed to report non‐concurrence in quality assessment.

Measures of treatment effect

The main outcome result was response to treatment. The improvement is usually presented as either a change in a depression scale(s) (mean and standard deviation), or as a dichotomous outcome (responder or non‐responder, remitted or not‐remitted), or both.

(1) Binary or dichotomous data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the random‐effects model risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive than odds ratio (Boissel 1999), and odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimation of the impression of the effect. For statistically significant results we calculated the number needed to treat to benefit or harm statistic (NNTB or NNTH) and its 95% CI using Visual Rx (http://www.nntonline.net/), taking account of the event rate in the control group.

(2) Continuous data

(a) Summary statistics

It was likely that different studies would use a variety of depression rating scales; therefore we used standardised mean difference (SMD). If all included studies had used the same instrument, we would have used mean differences (MD).

(b) Endpoint versus change data

We preferred to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values and are easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. When endpoint data were unavailable, we used the change data. If we used MD, we pooled results based on change data and endpoint data in the same analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

(1) Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are trials in which all participants receive both the control and intervention treatment but not in the same order. The major problem with this design of trial is a carry‐over effect from the first phase to the second phase of the study, especially if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As this is the case with depression, randomised cross‐over studies were eligible, but we would only use data up to the point of first cross‐over.

(2) Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two agomelatine arms, especially two appropriate dose groups of an antidepressant drug, the different dose arms were pooled and considered to be one. For dichotomous outcomes sample sizes and the event numbers were summed across groups. For continuous outcomes, means and standard deviations were grouped using the methods described in Chapter 7 (Section 7.7.3.8) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). In three‐armed trials with placebo groups, we only considered data from active treatments.

Dealing with missing data

We tried to contact the authors for all relevant missing data.

(1) Dichotomous outcomes

Response, or remission on treatment, was calculated using an intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT). We followed the principle 'once randomised always analyse'. In trials where participants left the study before the intended endpoint, it was be assumed that they would have experienced a negative outcome. The validity of the above assumption was tested by sensitivity analysis, applying worst‐case and best‐case scenarios. When dichotomous outcomes were not reported, but the baseline mean and standard deviation on a depression scale were reported, we calculated the number of responding or remitted participants according to a validated imputation method (Furukawa 2005). We analysed the validity of the above approach by sensitivity analysis.

(2) Continuous outcomes

The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends avoiding imputations of continuous data and suggests that the data must be used in the form they were presented by the original authors. We preferred ITT data, when available, to 'per‐protocol analysis'.

(3) Skewed or qualitative data

We presented skewed and qualitative data descriptively.

We considered several strategies for skewed data. If papers reported a mean and standard deviation, and there was also an absolute minimum possible value for the outcome, we divided the mean by the standard deviation. If this was less than two, then we concluded that there was some indication of skewness. If it was less than one (that is the standard deviation was bigger than the mean) then skewness was almost certainly present. If papers had not reported the skewness and simply reported means, standard deviations and sample sizes, these numbers were used. We did this because there was a possibility that these data may not have been properly analysed, and can also be misleading; we conducted analyses with and without these studies. If the data had been log‐transformed for analysis, and the geometric means were reported, skewness was reduced. This is the recommended method of analysis of skewed data. If papers used non‐parametric tests and described averages using medians, they could not be pooled formally in the analysis. We followed the recommendation made by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) that results of these studies are reported in a table in our review, along with all other papers. This meant that the data were not lost from the review and these results could be considered when drawing conclusions, even if they could not be pooled formally in the analyses.

(4) Missing statistics

When only P or standard error (SE) values were reported, we calculated standard deviations (SDs) (Altman 1996). In the absence of supplementary data after requests to the authors, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method (Furukawa 2006). We examined the validity of these imputations in the sensitivity analyses. We applied ITT analyses, in which all the drop outs not included in the analyses were considered to be non‐responders. We examined the validity of this decision in the sensitivity analyses by applying worst‐case and best‐case scenarios. We presented symptom levels as either continuous (mean ± SD) or dichotomous outcomes (improved or not improved).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions' recommendations (I2 statistic values 0% to 40%: might be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: represent considerable heterogeneity). We also used Chi2 and its P value to determine the direction and magnitude of the treatment effects. In a meta‐analysis of few trials, Chi2 will be underpowered to detect heterogeneity, if it exists. Therefore, a P value of less than 0.10 was used as the threshold for statistical significance (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). A funnel plot is usually used to investigate publication bias. However, it has a limited role when there are only a few studies of similar size. Secondly, asymmetry of a funnel plot does not always reflect publication bias. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes if there were 10 or fewer studies, or if all studies were of similar size.

Data synthesis

We used a random‐effects model to calculate the treatment effects. We preferred the random‐effects model as it takes in to account differences between studies even when there is no evidence of statistical heterogeneity. It gives a more conservative estimate than the fixed‐effect model. We note that the random‐effects model gives added weight to small studies, which can either increase or decrease the effect size. We also did the analysis using a fixed‐effect model to see whether it changed the effect size markedly.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We note that subgroup analyses are often exploratory in nature and should be interpreted very cautiously: firstly, because they often involve multiple analyses and this can lead to false positive results; and secondly, because these analyses lack power and are more likely to result in false positive results. Bearing the above reservations in mind, we performed the following subgroup analyses.

Agomelatine dosing (fixed low dosage: 25 mg/day; fixed high dosage: 50 mg and above; flexible high dose and flexible low dose). The standard dose of agomelatine is 25 mg to 50 mg per day. There is evidence to suggest that low dose antidepressants may be associated with better outcomes both in terms of effectiveness and tolerability (Bollini 1999). Similarly, fixed versus flexible dose can also affect the estimate of treatment effectiveness (Khan 2003).

Severity of depression (mild, moderate, severe depression). This analysis might have been useful in assessing the efficacy of agomelatine in different subpopulations of participants divided by severity.

Treatment settings (primary care, psychiatric inpatients, or psychiatric outpatients). This analysis might have been useful in identifying whether agomelatine could have been more or less effective in different treatment settings.

Older participants (participants aged 65 years or more) separately from other adult participants. This analysis might have been useful for finding out whether agomelatine could have more or less efficacy among older participants.

Examination of 'wish bias' by comparing agomelatine as the investigational drug versus agomelatine as the comparator, as there is evidence to suspect that a new antidepressant might perform worse when used as a comparator than when used as an experimental agent (Barbui 2004).

Examination of publication bias by assessing response to agomelatine in unpublished studies versus response to agomelatine in published studies. This analysis might be useful in determining whether there is a significant difference in reported outcome in published studies versus unpublished studies, in order to be able to assess publication bias.

If groups within any of the subgroups were found to be significantly different from one another, we planned to run meta‐regressions for exploratory analyses of additive or multiplicative influences of the variables in question.

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses were planned a priori. By limiting the included studies to those of higher quality, we examined whether the results changed, and checked for the robustness of the observed findings.

Excluding trials with unclear concealment of random allocation or unclear double blinding, or both; and trials with inadequate concealment of random allocation.

Excluding trials with drop‐out rates greater than 20%.

Performing the worst‐case scenario ITT (i.e. all the participants in the experimental group experienced the negative outcome and all those allocated to the comparison group experienced the positive outcome) and the best‐case scenario ITT (i.e. all the participants in the experimental group experienced the positive outcome and all those allocated to the comparison group experienced the negative outcome).

Excluding trials for which the response rates had to be calculated via the imputation method (Furukawa 2005), and those for which the SD had to be borrowed from other trials (Furukawa 2006).

Excluding all cross‐over trials.

Excluding studies funded by the pharmaceutical company marketing agomelatine (Servier). This sensitivity analysis is particularly important in view of the repeated findings that funding strongly affects the outcomes of research studies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Bhandari 2004; Lexchin 2003), and because industry sponsorship and authorship of clinical trial reports has increased over the last 20 years (Buchkowsky 2004).

Excluding studies in which there were any participants diagnosed with bipolar depression.

Our routine application of random‐effects and fixed‐effect models, as well as our secondary outcomes of remission rates and continuous severity measures, might be considered to be additional forms of sensitivity analyses.

'Summary of findings' table

A 'Summary of findings' (SoF) table was made for each comparison (agomelatine versus SSRI and agomelatine versus SNRI). Six outcomes were chosen to build the two tables, based on their importance (response rate, remission rates, total drop outs, drop out due to inefficacy, drop outs due to side effects, total number of participants experiencing at least one side effect). The SoF table is based on the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation) system (Rosenbaum 2010). The GRADE system is a formal way of evaluating the quality of evidence, using several parameters, in order to achieve transparency and simplicity (Guyatt 2008). Initially, evidence for each RCT is considered as high, and then downgraded for a variety of reasons, including study limitations, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision and reporting bias. On the basis of these criteria, the evidence can be downgraded to moderate, low or very low (Guyatt 2008). The inclusion of SoF tables in Cochrane reviews improves understanding and rapid retrieval of key findings (Rosenbaum 2010).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

Initially, we identified 120 references, 88 through database searching and 32 through other sources. These included 28 duplicates that were excluded, and a further 44 records were excluded after screening of abstracts. We retrieved full‐text copies of the remaining 48 references for more detailed evaluation. Thirty‐five studies were excluded for a variety of reasons. In the end, 13 studies were included in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis. The literature search was last updated in July 2013.

See Figure 1 for more details on the result of the search.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

A total of 13 studies was included in this systematic review. Four of these were unpublished trials carried out by a pharmaceutical company (Servier; CAGO2303; CL3‐022; CL3‐023; CL3‐024). Attempts to contact the pharmaceutical company (Servier) for additional information on all unpublished studies were unsuccessful. With the exception of one study (Martinotti 2012), requests to authors concerning missing data were also unsuccessful.

Design

All the included studies were randomised trials. Eleven were reported to be double blind, and one study used an open label parallel group design (Martinotti 2012). Five studies were three‐armed with agomelatine, an active comparator and placebo (CAGO2303; CL3‐022; CL3‐023; CL3‐024; Loo 2002a). Seven studies were two‐armed with agomelatine versus another antidepressant (Corruble 2013; Hale 2010; Kasper 2010; Kennedy 2008; Lemoine 2007; Martinotti 2012; Quera‐Salva 2011).

Sample sizes

Overall, the studies included 4495 participants in active treatment arms. Of these, 2457 were randomised to agomelatine. Of the remaining 2048 participants, 1701 were randomised to SSRIs: 862 to fluoxetine, 453 to paroxetine,159 to sertraline and 227 to escitalopram. The remaining 337 participants were randomised to an SNRI, venlafaxine. The mean sample size per arm was 156 participants (range 30 to 314). Only one study recruited fewer than 100 participants overall (Martinotti 2012).

Setting

All studies were multicentre trials. Three studies were conducted in a single nation, namely, the USA (CAGO2303), France (CL3‐022), and Italy (Martinotti 2012). One study was conducted in France and Spain (Lemoine 2007). One multinational study recruited Asian participants only (Shu 2013). The other studies were multinational across continents.

Three studies enrolled both inpatients and outpatients (CL3‐022; CL3‐023; CL3‐024). Eight studies recruited outpatients (Corruble 2013; Hale 2010; Kasper 2010; Kennedy 2008; Lemoine 2007; Martinotti 2012; Quera‐Salva 2011; Shu 2013). Two studies did not report the setting (CAGO2303; Loo 2002a).

Participants

All studies included participants with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). One study also included participants with bipolar II depression (Loo 2002a), although the proportion suffering from this condition was no more than 3%. As per our protocol for the review, Loo 2002a was included in the present review as less than 20% of the participants in the study had bipolar disorder.

All studies randomised participants from 18 years of age, but the age ranges recruited varied: two studies recruited participants up to 70 years of age (CAGO2303; Corruble 2013); three studies recruited between the ages of 18 to 59 years (CL3‐022; CL3‐023; CL3‐024); four studies recruited between the ages of 18 to 60 (Kasper 2010; Kennedy 2008; Martinotti 2012; Quera‐Salva 2011); and the final four studies recruited between the ages of 18 to 65 (Hale 2010; Lemoine 2007; Loo 2002a; Shu 2013).

Interventions and comparators

Most studies compared agomelatine to SSRIs: three compared agomelatine to paroxetine (CAGO2303; CL3‐023; Loo 2002a); four compared agomelatine to fluoxetine (CL3‐022; CL3‐024; Hale 2010; Shu 2013); two compared agomelatine to escitalopram (Corruble 2013; Quera‐Salva 2011); and one compared agomelatine to sertraline (Kasper 2010). Three studies compared agomelatine to an SNRI, venlafaxine (Kennedy 2008; Lemoine 2007; Martinotti 2012).

Outcomes

Efficacy data (either as dichotomous or as continuous outcome) and tolerability/acceptability data were available for all 13 included studies and could be entered into a meta‐analysis.

All but one study used HAM‐D as rating scale for primary or secondary outcome measures; Kennedy 2008 used MADRS instead. Ten studies reported response rates: data for one study was provided by the authors upon request (Martinotti 2012), and we imputed response rates for the remaining two studies from continuous data (CL3‐023; CL3‐024). Seven studies reported remission rates: data for one study was provided by the authors upon request (Martinotti 2012), and we imputed remission rates for the remaining five studies from continuous data (CL3‐023; CL3‐024; Lemoine 2007; Quera‐Salva 2011; Shu 2013).

All but one study reported drop outs due to any reason (Kennedy 2008). Nine studies reported drop outs due to side effects (CAGO2303; CL3‐022; CL3‐023; Corruble 2013; Hale 2010; Kasper 2010; Loo 2002a; Quera‐Salva 2011; Shu 2013), and the same nine also reported drop outs due to inefficacy. Six studies reported the total number of participants who experienced side effects (CAGO2303; Hale 2010; Kasper 2010; Loo 2002a; Quera‐Salva 2011; Shu 2013).

Excluded studies

Overall, we excluded 20 studies from the systematic review because of the inclusion criteria. Nineteen of these did not have an active control group and one trial was withdrawn prior to enrolment (see Characteristics of excluded studies and Figure 1).

Ongoing studies

We identified six ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies) (CL3‐060; CL3‐074; CL3‐083; GENRAS; Lundbeck 2011; NCT01483053).

Studies awaiting classification

We classified nine studies as awaiting classification (CL3‐027; CL3‐048; CL3‐062; CL3‐073; CRSC11003; CTRI/2011/04/001659; Karaiskos 2013; Montgomery 2004; Vasile 2011. Those trials were either published (Karaiskos 2013; Montgomery 2004), included in EMEA documents (CL3‐027; CL3‐048; CL3‐062; CL3‐073), retreived from Clinical Trial Registry India (CRSC11003; CTRI/2011/04/001659) or retreived from conference proceedings (Vasile 2011). One of the published studies was designed to examine withdrawal symptoms (Montgomery 2004); data for the first 12 weeks of the study, comparing agomelatine (25 mg/day) and paroxetine (20 mg/day) were not adequately reported to be included (see: Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). The other published study was rated as awaiting classification because it was unclear whether the trial was randomised (Karaiskos 2013); a request to the authors remains unanswered.

Risk of bias in included studies

See: Characteristics of included studies, Figure 2, Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

The overall methodological quality of the studies was not very good; every study judged as having high or unclear risk of bias in at least one domain (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 for summary graphs). Almost all of the studies were sponsored by the pharmaceutical company that manufactures agomelatine (Servier), and some of them were unpublished. This last source of bias should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

Allocation

Ten studies reported no details about the randomisation procedure and so were judged as having unclear risk of bias (CAGO2303; CL3‐022; CL3‐023; CL3‐024; Hale 2010; Kasper 2010; Kennedy 2008; Lemoine 2007; Loo 2002a; Shu 2013). One study reported that randomisation was non‐adaptive, balanced, and stratified on the centre and that an interactive computer‐based system allocated a therapeutic unit number (Martinotti 2012). One study reported that randomisation was balanced but, did not provide any more details on the sequence generation (Quera‐Salva 2011).

Blinding

All RCTs apart from Martinotti 2012 were reported as double blind and so were deemed to have low risk of bias. Martinotti 2012, which was an open‐label parallel group trial, was judged as having a high risk of bias in this domain. All but two double‐blind studies reported details of measures employed to ensure successful blinding (CAGO2303; Loo 2002a).

Incomplete outcome data

Overall, the drop out rate was around 18% for agomelatine and 19% for the control medication; this ranged from 10% in Quera‐Salva 2011 to 22% in CAGO2303. Three studies had a drop‐out rate of more than 20% (CAGO2303; CL3‐024; Loo 2002a).

Selective reporting

Study protocols were not available for all the studies. Data from CL3‐022; CL3‐023; CL3‐024 were limited, as we could not gain access to the full dataset because the studies were unpublished; attempts to obtain data from the pharmaceutical company manufacturing agomelatine (Servier) were unsuccessful. Loo 2002a, CL3‐022, CL3‐023 and CL3‐024 were not registered, thus increasing risk of selective reporting, and Martinotti 2012 did not report full data on adverse events. CL3‐022, CL3‐023, CL3‐024, Loo 2002a, Martinotti 2012 and Corruble 2013 were all judged as having a high risk of bias in this domain. The risk of bias in Shu 2013 was assessed as unclear, and the remaining studies were deemed as having low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

All but two of the included RCTs were sponsored by the company that manufactures agomelatine (Servier) and so were assessed as having high risk of bias. Martinotti 2012 was funded by a research department without industry support and it was unclear whether Loo 2002a was sponsored or not, so these two studies were assessed as having unclear risk of bias in this domain.

Effects of interventions

We have reported the results of the present systematic review by grouping the comparators into three classes: SSRIs, SNRIs and other antidepressive agents. Where possible, each comparator is presented in subgroups.

Comparison one: agomelatine versus other SSRIs

Primary outcome

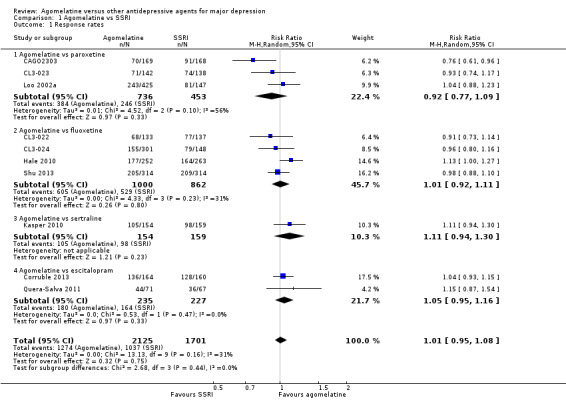

1.1 Efficacy ‐ number of participants who responded to treatment

There was no evidence that agomelatine was less or more effective than SSRIs as a whole (Mantel‐Haenszel risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.95 to 1.08, P value 0.75; 10 trials, 3826 participants), statistical heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 31%). Considering each comparator, there was no evidence that agomelatine was less or more effective than: paroxetine (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.09, P value 0.33, I² = 56%; three trials, 1189 participants); fluoxetine (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.11, P value 0.80, I² = 31%; four trials, 1862 participants); sertraline (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.30, P value 0.23, one trial, 313 participants); or escitalopram (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.16, P value 0.33, I² = 0%; two trials, 462 participants) (see Analysis 1.1 and Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 1 Response rates.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, outcome: 1.1 Response rates

Secondary outcomes

1.2 Efficacy ‐ number of participants who achieve remission

There was no significant difference in the number of participants who achieved remission between agomelatine and SSRIs as a whole (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.01, P value 0.07; ten trials, 3826 participants). Heterogeneity was substantial between studies (I² = 78%). There was no significant difference in the number of participants who achieved remission between: agomelatine and paroxetine (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.18, P value 0.14, I² = 84%; three trials, 1189 participants); fluoxetine (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.05, P value 0.10, I² = 84%; four trials, 1862 participants); sertraline (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.58, P value 0.50; one trial, 313 participants); and escitalopram (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.35, P value 0.20, I² = 0%; two trials, 462 participants) (see Analysis 1.2 and Figure 5).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 2 Remission rates.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, outcome: 1.2 Remission rates

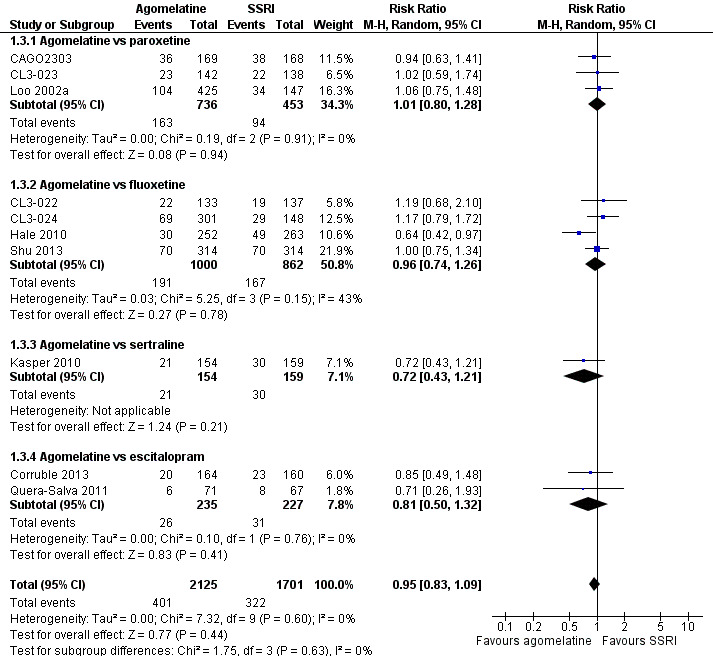

1.3 Acceptability ‐ total drop‐out rate

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher total drop‐out rate than SSRIs as a whole (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.09, P value 0.44, I² = 0%; ten trials, 3826 participants). There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher total drop‐out rate than: paroxetine (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.28, P value 0.94; three trials, 1189 participants); fluoxetine (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.26, P value 0.78, I² = 43%; four trials, 1862 participants); sertraline (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.21, P value 0.21; one trial, 313 participants); and escitalopram (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.32, P value 0.76, I² = 0%; two trials, 462 participants) (see Analysis 1.3 and Figure 6).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 3 Total drop outs.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, outcome: 1.3 Total drop outs

1.4 Acceptability ‐ drop‐out rates due to inefficacy

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher drop‐out rate due to inefficacy than SSRIs as a whole (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.37, P value 0.95, I² = 0%; nine trials, 3377 participants). There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher drop‐out rate due to inefficacy than: paroxetine (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.80, P value 0.80, I² = 0%; three trials, 1189 participants); fluoxetine (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.65, P value 0.91, I² = 17%; three trials, 1413 participants); sertraline (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.68, P value 0.27; one trial, 313 participants); or escitalopram (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.43 to 4.21, P value 0.61, I² = 0%; two trials, 462 participants) (see Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 4 Drop out due to inefficacy.

1.5 Acceptability ‐ drop‐out rates due to side effects

There was evidence that fewer participants dropped out due to side effects when treated with agomelatine compared to other SSRIs as a whole (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.91, P value 0.009, I² = 0%; nine studies, 3377 participants, NNTH = 47).

There was no evidence that fewer or more people dropped out due to side effects when treated with agomelatine compared to: paroxetine (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.41, P value 0.49, I² = 0%; three studies, 1189 participants); fluoxetine (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.09, P value 0.13, I² = 0%; three studies, 1413 participants); and escitalopram (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.06, P value 0.07; two studies, 462 participants). There was some evidence (albeit with a small effect size) that agomelatine was associated with a lower drop‐out rate due to side effects compared to sertraline (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.00, P value 0.05; one study, 313 participants, NNTH = 18) (see Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 5 Drop outs due to side effects.

1.6 Tolerability ‐ total number of participants experiencing at least some side effects

There was evidence (albeit with a small effect size) that fewer participants experienced side effects when treated with agomelatine than when treated with other SSRIs as a whole (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.98, P value 0.01, I² = 28%; six studies, 2490 participants, NNTH = 23).

There was evidence that fewer participants experienced at least some side effects when treated with agomelatine compared to paroxetine (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.94, P value 0.0010, I² = 0%; two studies, 905 participants, NNTH = 7). There was no evidence that fewer or more participants experienced at least some side effects when treated with agomelatine compared to either fluoxetine (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.11, P value 0.95, I² = 0%; two studies, 1141 participants) or sertraline (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.23, P value 0.86; one study, 307 participants). There was some evidence (albeit with a small effect size) that agomelatine was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing side effects compared to escitalopram (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.99, P value 0.04; one study, 137 participants, NNTH = 6). See Analysis 1.6.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 6 Total number of patients with side effects.

We also analysed the six outcomes above using a fixed‐effect model; this produced no change in significance levels and only negligible changes in effect sizes.

1.7 Tolerability ‐ total number of participants experiencing specific side effects

(a) Sleepiness or drowsiness

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing sleepiness or drowsiness compared to all other SSRIs as a group (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.15, P value 0.92, I² = 68%; five studies, 1868 participants).

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing sleepiness or drowsiness than: paroxetine (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.21, P value 0.16; two studies, 905 participants); fluoxetine (RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.78 to 3.93, P value 0.17; one study, 513 participants); or escitalopram (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.55, P value 0.12; one study, 137 participants). There was evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing sleepiness or drowsiness compared to sertraline (RR 4.65, 95% CI 1.02 to 21.16, P value 0.05; one study, 313 participants, NNTH = 22) (see Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 7 Sleepiness or drowsiness.

(b) Insomnia

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing Insomnia compared to other SSRIs as a group (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.59, P value 0.49, I² = 14%; two studies, 1192 participants).

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing insomnia than paroxetine (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.38, P value 0.20; one study, 572 participants) or fluoxetine (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.88, P value 0.81; one study, 620 participants) (see Analysis 1.8). No data were available for sertraline or escitalopram for this outcome.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 8 Insomnia.

(c) Dry mouth

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing dry mouth compared to all other SSRIs as a group (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.40, P value 0.77, I² = 0%; five studies, 2349 participants).

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing dry mouth than: paroxetine (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.57, P value 0.71; two studies, 905 participants); fluoxetine (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.89, P value 0.92, I² = 0%; two studies, 1133 participants); or sertraline (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.72, P value 0.93; one study, 311 participants) (see Analysis 1.9). No data were available for escitalopram for this outcome.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 9 Dry mouth.

(d) Constipation

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing constipation than fluoxetine (RR 2.81, 95% CI 0.75 to 10.46, P value 0.12; one study, 513 participants). See Analysis 1.10. No data were available for paroxetine, sertraline and escitalopram for this outcome.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 10 Constipation.

(e) Dizziness

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing dizziness compared to all other SSRIs as a group (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.55; P value 0.99, I² = 3%; four studies, 1603 participants).

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing dizziness than: paroxetine (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.96, P value 0.62; one study, 333 participants); fluoxetine (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.94, P value 0.54; I² = 0%; two studies, 1133 participants); or escitalopram (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.03, P value 0.19; one study, 137 participants) (see Analysis 1.11). No data were available for sertraline for this outcome.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 11 Dizziness.

(f) Hypotension

None of the included studies reported data for this outcome.

(g) Agitation or anxiety

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing agitation or anxiety compared to other SSRIs as a group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.27, P value 0.97, I² = 0%; two studies, 1192 participants).

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing agitation and anxiety than paroxetine (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.40 to 3.62, P value 0.73; one study, 572 participants) or fluoxetine (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.26 to 2.70, P value 0.76; one study, 620 participants) (see Analysis 1.12). No data were available for sertraline and escitalopram for this outcome.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 12 Agitation or anxiety.

(h) Suicide wishes, gestures or attempts

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing suicide wishes, gestures or attempts than paroxetine (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.17 to 4.41, P value 0.86; one study, 572 participants) (see Analysis 1.13). No data were available for fluoxetine, sertraline and escitalopram for this outcome.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 13 Suicide wishes, gestures or attempts.

(i) Completed suicide

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a higher rate of participants completing suicide than paroxetine (RR 0.35 , 95% CI 0.02 to 5.49, P value 0.45; one study, 572 participants) (see Analysis 1.14). No data were available for fluoxetine, sertraline and escitalopram for this outcome.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 14 Completed suicide.

(j) Vomiting or nausea

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing vomiting or nausea compared to all other SSRIs as a group (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.45, P value 0.34, I² = 83%; five studies, 2175 participants).

There was evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing vomiting or nausea than paroxetine (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.52, P value < 0.00001, I² = 0%; two studies, 905 participants, NNTH = 9) There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing vomiting or nausea compared to fluoxetine (RR 1.54, 95% CI 0.30 to 7.90, P value 0.60, I² = 90%; two studies, 1133 participants) or escitalopram (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.61, P value 0.35; one study, 137 participants) (see Analysis 1.15). No data were available for sertraline for this outcome.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 15 Vomiting or nausea.

(k) Diarrhoea

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing diarrhoea compared to all other SSRIs as a group (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.40, P value 0.43, I² = 0%; four studies, 1533 participants).

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher rate of participants experiencing diarrhoea than: paroxetine (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.43, P value 0.21; one study, 572 participants); fluoxetine (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.96, P value 0.92; one study, 513 participants); sertraline (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.91, P value 0.48; one study, 311 participants); or escitalopram (RR 1.86, 95% CI 0.35 to 9.82, P value 0.47; one study, 137 participants) (see Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 16 Diarrhoea.

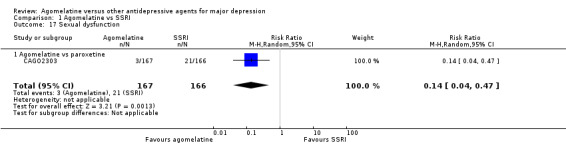

(l) Sexual dysfunction

There was evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing sexual dysfunction than paroxetine (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.47, P value 0.001; one study, 333 participants, NNTH = 9) (see Analysis 1.17). No data were available for fluoxetine, sertraline and escitalopram for this outcome.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 17 Sexual dysfunction.

(m) Abnormal liver function tests

There was no statistically significant higher rate of abnormal liver function tests in participants treated with agomelatine compared to all other SSRIs as a group (RR 3.04, 95% CI 0.90 to 10.22, P value 0.07, I² = 0%; four studies, 1755 participants).

There was no statistically significant higher rate of abnormal liver function tests in participants treated with agomelatine compared to: paroxetine (RR 3.04, 95% CI 0.32 to 28.89, P value 0.33; one study, 318 participants); fluoxetine (RR 3.02, 95% CI 0.60 to 15.17, P value 0.18; two studies, 1124 participants); or sertraline (RR 3.10, 95% CI 0.13 to 75.44, P value 0.49; one study, 313 participants). See Analysis 1.18. No data were available for escitalopram for this outcome.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 18 Abnormal liver function tests.

(n) Weight gain

No data reported for this outcome.

(o) Hypertension

No data reported for this outcome.

1.8 Continuous outcome ‐ depression scale endpoint score

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a statistically significant difference compared to the other SSRIs as a group (SMD 0.00; 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.12, P value 0.94, I² = 66%; ten studies, 3457 participants). There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher depression endpoint score compared to: paroxetine (SMD 0.16; 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.43, P value 0.24, I² = 75%; three studies, 882 participants); fluoxetine (SMD ‐0.01; 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.13, P value 0.87, I² = 54%; four studies, 1816 participants); or escitalopram (SMD ‐0.08; 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.11, P value 0.42, I² = 0%; two studies, 453 participants).There was a small but statistically significant advantage of agomelatine compared to sertraline (SMD ‐0.23; 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.01, P value 0.04; one study, 306 participants) (see Analysis 1.19).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agomelatine vs SSRI, Outcome 19 Depression scales endpoint score.

Comparison two: agomelatine versus other SNRIs

Primary outcome

2.1 Efficacy ‐ number of participants who responded to treatment

There was no evidence that agomelatine was less or more effective than venlafaxine (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.16, P value 0.16, I² = 0%; three trials, 669 participants) (see Analysis 2.1 and Figure 7).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, Outcome 1 Response rates.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, outcome: 2.1 Response rates

Secondary outcomes

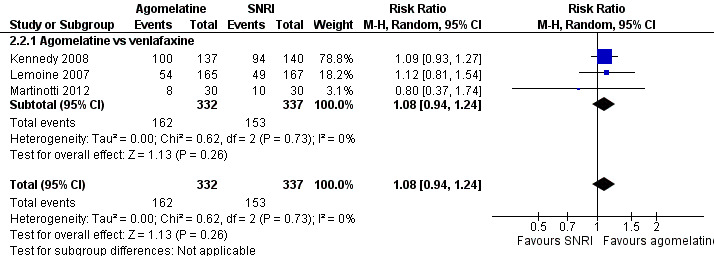

2.2 Efficacy ‐ number of participants who achieved remission

There was no significant difference in the number of participants who achieved remission between agomelatine and venlafaxine (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.24, P value 0.26, I² = 0%; three trials, 669 participants) (see Analysis 2.2 and Figure 8).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, Outcome 2 Remission rates.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, outcome: 2.2 Remission rates

2.3 Acceptability ‐ total drop‐out rate

There was evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower total drop‐out rate than venlafaxine (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.67, P value 0.0005, I² = 0%; two trials, 392 participants, NNTB = 2) (See Analysis 2.3 and Figure 9).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, Outcome 3 Total drop outs.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, outcome: 2.3 Total drop outs

2.4 Acceptability ‐ drop‐out rates due to inefficacy

There was no evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower or higher drop‐out rate due to inefficacy compared to venlafaxine (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.21 to 4.94, P value 0.99; one trial, 332 participants) (see Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, Outcome 4 Drop out due to inefficacy.

2.5 Acceptability ‐ drop‐out rates due to side effects

There was evidence that agomelatine was associated with a lower drop‐out rate due to side effects compared to venlafaxine (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.59, P value 0.0006, I² = 0%; two trials, 608 participants, NNTH = 13) (see Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, Outcome 5 Drop outs due to side effects.

2.6 Tolerability ‐ total number of participants experiencing at least some side effects

There was no evidence that fewer or more participants experienced at least some side effects compared to venlafaxine (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.18, P value 0.19, I² = 80%; two trials, 611 participants) (see Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Agomelatine vs SNRI, Outcome 6 Total number of patients with side effects.

We also analysed the six outcomes above using a fixed‐effect model and noted no change in significance levels and only negligible changes in effect sizes.