Abstract

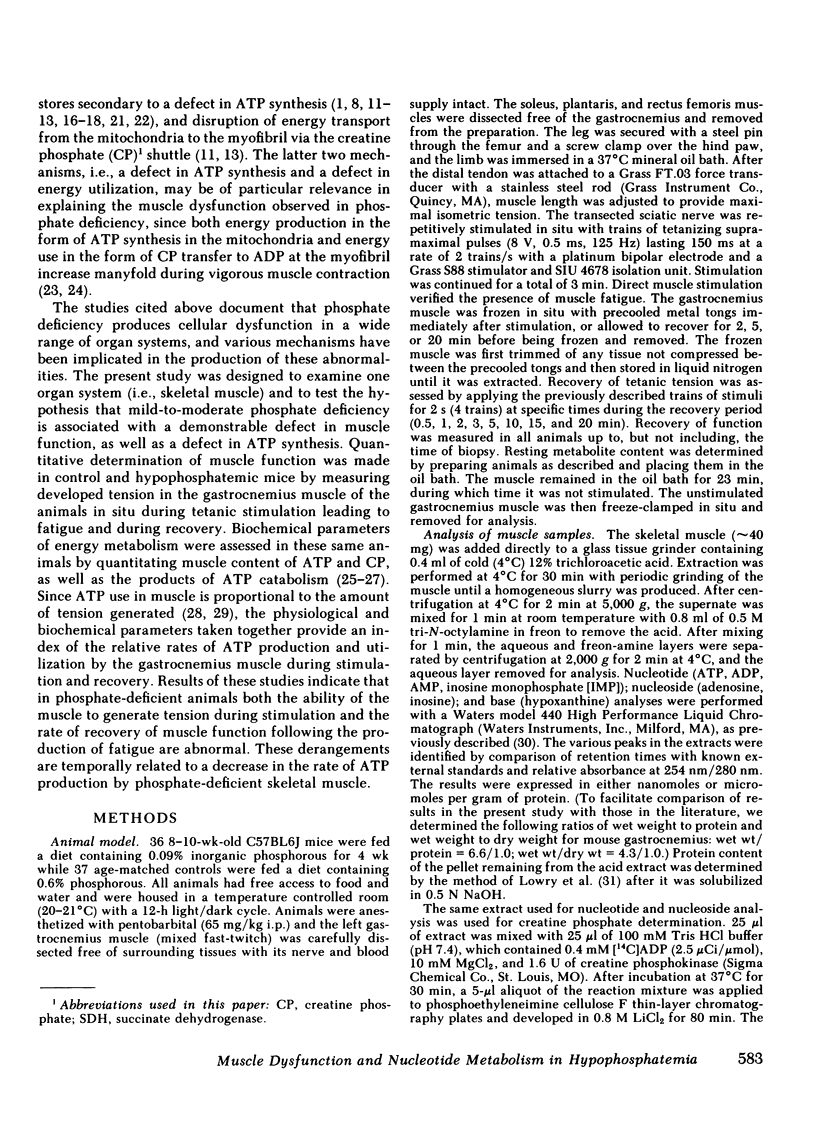

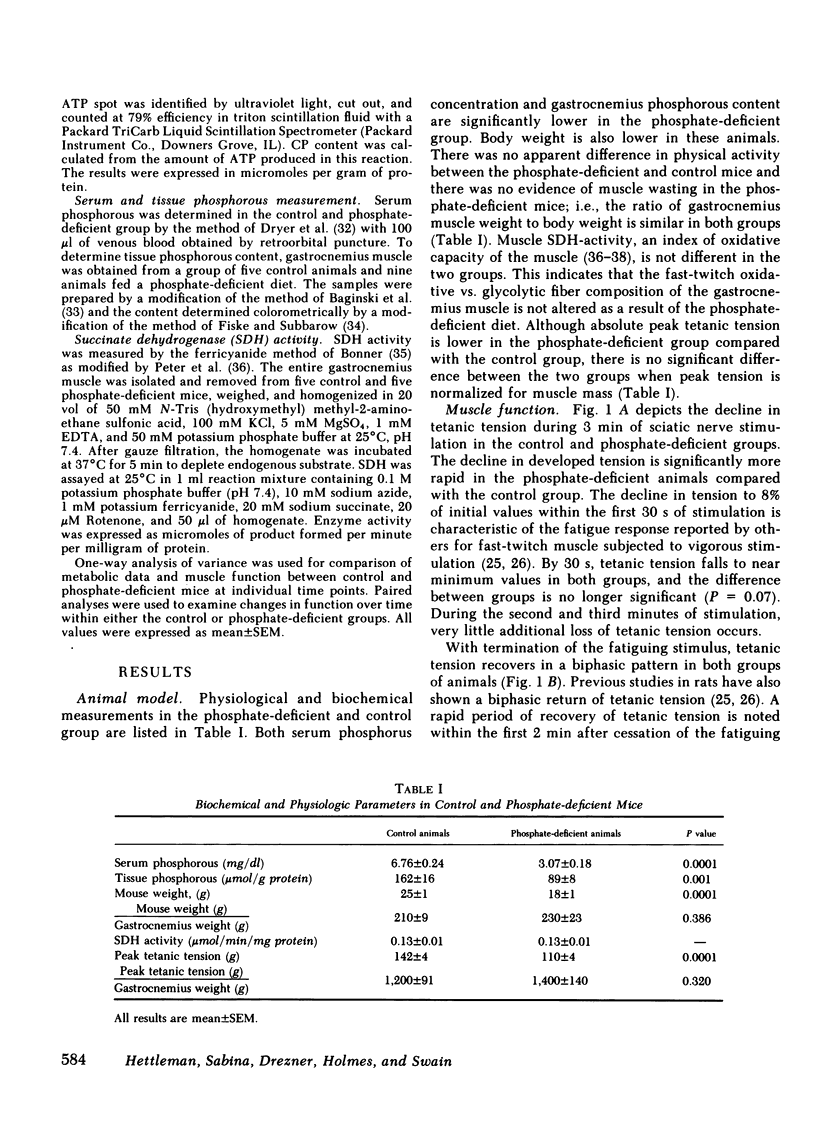

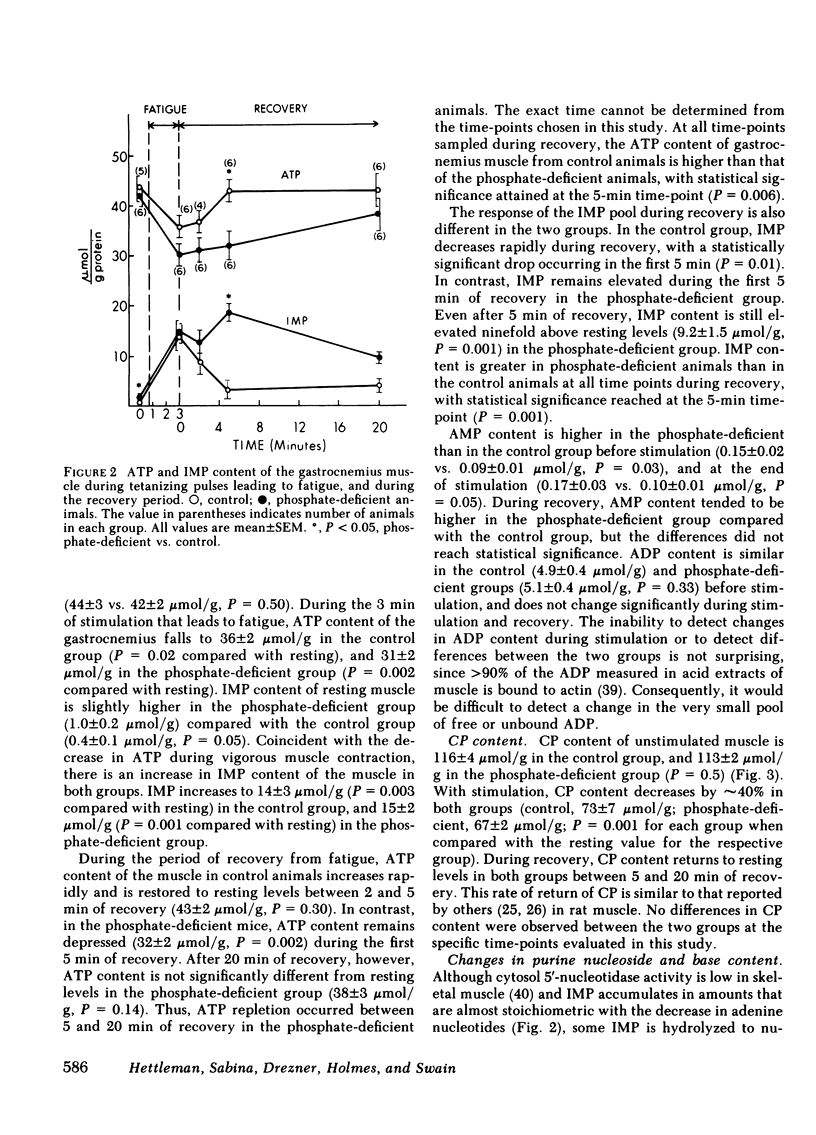

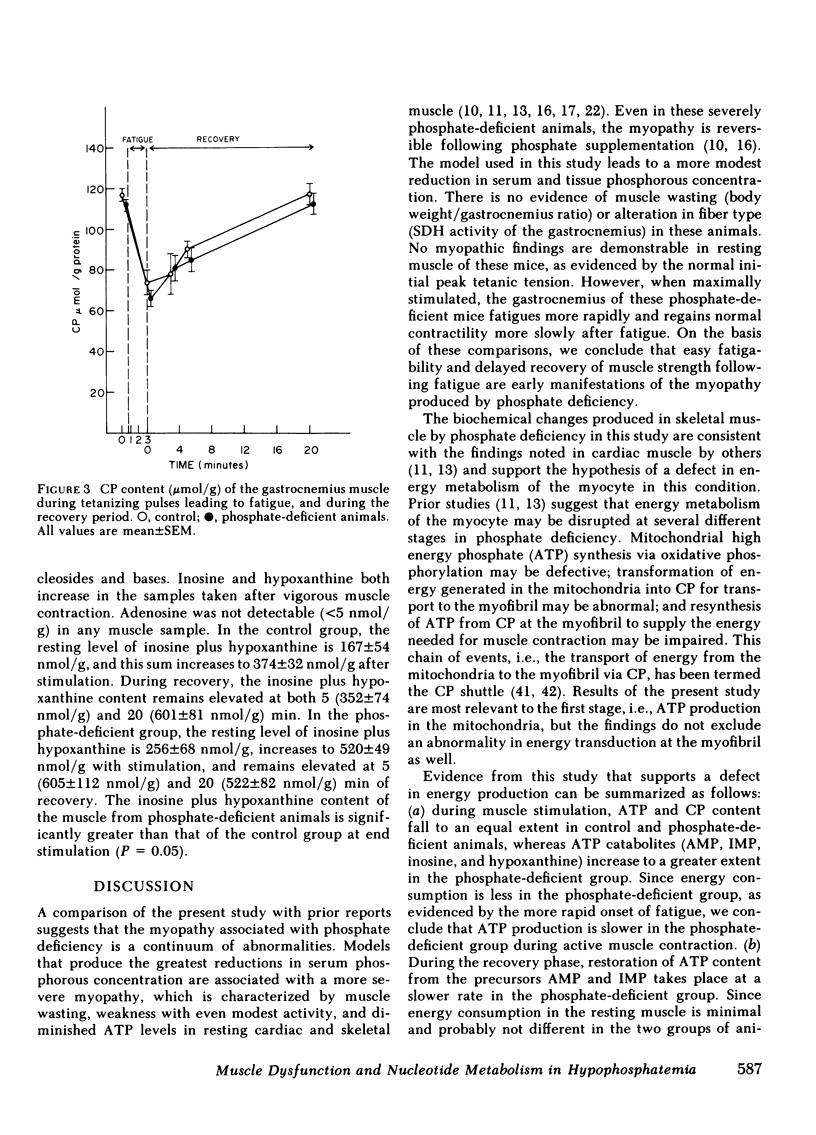

The basis for skeletal muscle dysfunction in phosphate-deficient patients and animals is not known, but it is hypothesized that intracellular phosphate deficiency leads to a defect in ATP synthesis. To test this hypothesis, changes in muscle function and nucleotide metabolism were studied in an animal model of hypophosphatemia. Mice were made hypophosphatemic through restriction of dietary phosphate intake. Gastrocnemius function was assessed in situ by recording isometric tension developed after stimulation of the nerve innervating this muscle. Changes in purine nucleotide, nucleoside, and base content of the muscle were quantitated at several time points during stimulation and recovery. Serum concentration and skeletal muscle content of phosphorous are reduced by 55 and 45%, respectively, in the dietary restricted animals. The gastrocnemius muscle of the phosphate-deficient mice fatigues more rapidly compared with control mice. ATP and creatine phosphate content fall to a comparable extent during fatigue in the muscle from both groups of animals; AMP, inosine, and hypoxanthine (indices of ATP catabolism) appear in higher concentration in the muscle of phosphate-deficient animals. Since total ATP use in contracting muscle is closely linked to total developed tension, we conclude that the comparable drop in ATP content in association with a more rapid loss of tension is best explained by a slower rate of ATP synthesis in the muscle of phosphate-deficient animals. During the period of recovery after muscle stimulation, ATP use for contraction is minimal, since the muscle is at rest. In the recovery period, ATP content returns to resting levels more slowly in the phosphate-deficient than in the control animals. In association with the slower rate of ATP repletion, the precursors inosine monophosphate and AMP remain elevated for a longer period of time in the muscle of phosphate-deficient animals. The slower rate of ATP repletion correlates with delayed return of normal muscle contractility in the phosphate-deficient mice. These studies suggest that the slower rate of repletion of the ATP pool may be the consequence of a slower rate of ATP synthesis and this is in part responsible for the delayed recovery of normal muscle contractility.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bessman S. P., Geiger P. J. Transport of energy in muscle: the phosphorylcreatine shuttle. Science. 1981 Jan 30;211(4481):448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.6450446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautbar N., Baczynski R., Carpenter C., Massry S. G. Effects of phosphate depletion on the myocardium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;151:199–207. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4259-5_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautbar N., Baczynski R., Carpenter C., Moser S., Geiger P., Finander P., Massry S. G. Impaired energy metabolism in rat myocardium during phosphate depletion. Am J Physiol. 1982 Jun;242(6):F699–F704. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.242.6.F699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal F., Schmalbruch H. Motor unit of mammalian muscle. Physiol Rev. 1980 Jan;60(1):90–142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1980.60.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R. E. Motor unit properties and selective involvement in movement. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1975;3:31–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B., Eleff S., Leigh J. S., Jr, Sokolow D., Sapega A. Mitochondrial regulation of phosphocreatine/inorganic phosphate ratios in exercising human muscle: a gated 31P NMR study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Nov;78(11):6714–6718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock P. R., Yawata Y., VanSanten L., Gilberstadt S., Silvis S., Jacob H. S. Acquired phagocyte dysfunction. A complication of the hypophosphatemia of parenteral hyperalimentation. N Engl J Med. 1974 Jun 20;290(25):1403–1407. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197406202902504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRYER R. L., TAMMES A. R., ROUTH J. I. The determination of phosphorus and phosphatase with N-phenyl-p-phenylenediamine. J Biol Chem. 1957 Mar;225(1):177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller T. J., Carter N. W., Barcenas C., Knochel J. P. Reversible changes of the muscle cell in experimental phosphorus deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1976 Apr;57(4):1019–1024. doi: 10.1172/JCI108343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller T. J., Nichols W. W., Brenner B. J., Peterson J. C. Reversible depression in myocardial performance in dogs with experimental phosphorus deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1978 Dec;62(6):1194–1200. doi: 10.1172/JCI109239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante A. A., Davies R. E. The effect of 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene on the activity of striated muscle. J Biol Chem. 1965 Oct;240(10):3996–4001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob H. S., Amsden T. Acute hemolytic anemia with rigid red cells in hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 1971 Dec 23;285(26):1446–1450. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klock J. C., Williams H. E., Mentzer W. C. Hemolytic anemia and somatic cell dysfunction in severe hypophosphatemia. Arch Intern Med. 1974 Aug;134(2):360–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochel J. P., Bilbrey G. L., Fuller T. J., Carter N. W. The muscle cell in chronic alcoholism: the possible role of phosphate depletion in alcoholic myopathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975 Apr 25;252:274–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb19168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochel J. P. Hypophosphatemia. West J Med. 1981 Jan;134(1):15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochel J. P. The pathophysiology and clinical characteristics of severe hypophosphatemia. Arch Intern Med. 1977 Feb;137(2):203–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz J., Sommer G., Boland R., Kreusser W., Hasselbach W., Ritz E. Lack of involvement of sarcoplasmic reticulum in myopathy of acute phosphorous depletion. Klin Wochenschr. 1980 Aug 15;58(16):833–837. doi: 10.1007/BF01491104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman M. A., Miller D. R., Cohen J., Waterhouse C. Reduced red cell glycolysis, 2, 3-diphosphoglycerate and adenosine triphosphate concentration, and increased hemoglobin-oxygen affinity caused by hypophosphatemia. Ann Intern Med. 1971 Apr;74(4):562–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-4-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz M., Zisman E., Bartter F. C. Evidence for a phosphorus-depletion syndrome in man. N Engl J Med. 1968 Feb 22;278(8):409–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196802222780802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. A., Terjung R. L. AMP deamination and IMP reamination in working skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1980 Jul;239(1):C32–C38. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1980.239.1.C32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. A., Terjung R. L. Differences in ammonia and adenylate metabolism in contracting fast and slow muscle. Am J Physiol. 1979 Sep;237(3):C111–C118. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1979.237.3.C111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. H., Neff T. A., Ziporin P. Acute respiratory failure associated with hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 1977 May 12;296(19):1101–1103. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197705122961908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor L. R., Wheeler W. S., Bethune J. E. Effect of hypophosphatemia on myocardial performance in man. N Engl J Med. 1977 Oct 27;297(17):901–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197710272971702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter J. B., Barnard R. J., Edgerton V. R., Gillespie C. A., Stempel K. E. Metabolic profiles of three fiber types of skeletal muscle in guinea pigs and rabbits. Biochemistry. 1972 Jul 4;11(14):2627–2633. doi: 10.1021/bi00764a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid M., Robson M. Proximal myopathy caused by latrogenic phosphate depletion. JAMA. 1976 Sep 20;236(12):1380–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks V. A., Kupriyanov V. V., Elizarova G. V., Jacobus W. E. Studies of energy transport in heart cells. The importance of creatine kinase localization for the coupling of mitochondrial phosphorylcreatine production to oxidative phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1980 Jan 25;255(2):755–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvis S. E., Paragas P. D., Jr Paresthesias, weakness, seizures, and hypophosphatemia in patients receiving hyperalimentation. Gastroenterology. 1972 Apr;62(4):513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain J. L., Sabina R. L., McHale P. A., Greenfield J. C., Jr, Holmes E. W. Prolonged myocardial nucleotide depletion after brief ischemia in the open-chest dog. Am J Physiol. 1982 May;242(5):H818–H826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.5.H818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis S. F., Sugerman H. J., Ruberg R. L., Dudrick S. J., Delivoria-Papadopoulos M., Miller L. D., Oski F. A. Alterations of red-cell glycolytic intermediates and oxygen transport as a consequence of hypophosphatemia in patients receiving intravenous hyperalimentation. N Engl J Med. 1971 Sep 30;285(14):763–768. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197109302851402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veech R. L., Lawson J. W., Cornell N. W., Krebs H. A. Cytosolic phosphorylation potential. J Biol Chem. 1979 Jul 25;254(14):6538–6547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawata Y., Hebbel R. P., Silvis S., Howe R., Jacob H. Blood cell abnormalities complicating the hypophosphatemia of hyperalimentation: erythrocyte and platelet ATP deficiency associated with hemolytic anemia and bleeding in hyperalimented dogs. J Lab Clin Med. 1974 Nov;84(5):643–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]