Abstract

Our sensory adaptation to cold and chemically induced coolness is mediated by the intrinsic property of TRPM8 channels to desensitize. TRPM8 is also implicated in cold-evoked pain disorders and migraine, highlighting its inhibitors as an avenue for pain relief. Despite the importance, the mechanisms of TRPM8 desensitization and inhibition remained unclear. We found, using cryo–electron microscopy, electrophysiology, and molecular dynamics simulations, that TRPM8 inhibitors bind selectively to the desensitized state of the channel. These inhibitors were used to reveal the overlapping mechanisms of desensitization and inhibition and that cold and cooling agonists share a common desensitization pathway. Furthermore, we identified the structural determinants crucial for the conformational change in TRPM8 desensitization. Our study illustrates how receptor-level conformational changes alter cold sensation, providing insights into therapeutic development.

Studies of TRPM8 desensitization and inhibition offer insights into mammalian cold adaptation and therapeutic development.

INTRODUCTION

Neural adaptation refers to the reduction of neuronal activity after prolonged or repeated exposure to a certain stimulus. This ubiquitous phenomenon occurs along the neuronal pathway—from the sensory periphery to the central nervous system and, lastly, the motor output—and is observed in both invertebrates and vertebrates (1). Adaptation to sensory stimuli (sensory adaptation) is applicable to all human sensations, including olfaction, touch, taste, hearing, and temperature sensation, which are mediated by specialized sensory receptors at the molecular level (2). The molecular and structural bases of sensory adaptation mechanisms remain largely elusive.

TRPM8 is expressed in dorsal root and trigeminal ganglion neurons and is the sensor for cold (8° to 28°C) and chemically induced coolness (3). TRPM8-deficient mice show severe behavioral deficiency not only in response to cold stimuli but also in injury-induced cold hypersensitivity, demonstrating the crucial role of TRPM8 in cold-induced pain and cold sensing (4, 5). Channel activation by either cold or chemical coolness requires the signaling lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2 or PIP2] (6–8). TRPM8 agonists are classified as either type I (menthol-like) or type II [allyl isothiocyanate (AITC)–like] based on their distinct kinetics (9) and binding sites (10). TRPM8 is a homotetrameric channel composed of the transmembrane channel domain (TMD), with transmembrane helices S1 to S6, and the cytoplasmic melastatin homology regions (MHRs) 1 to 4 (fig. S1) (11). Recently, the allosteric coupling between PIP2 and type I and type II agonists was used to capture cryo–electron microscopy (EM) structures of the mouse (Mus musculus) TRPM8 (TRPM8MM) in distinct closed (C) and open (O) conformations along the ligand-gating pathway, illuminating the mechanism of channel activation through synergistic ligands (Fig. 1A) (10).

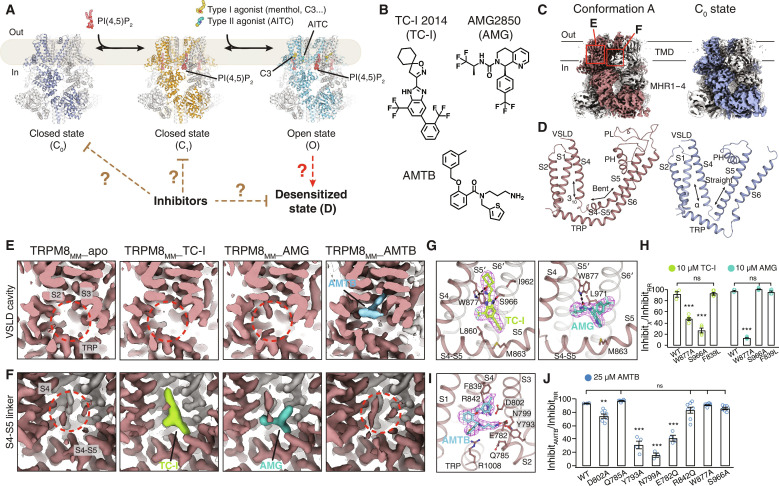

Fig. 1. Cryo-EM structure determination of TRPM8MM in complex with antagonists.

(A) Cartoon diagram of the PIP2 and cooling agonist-dependent gating pathway of TRPM8 channels. Published TRPM8MM structures in the C0, C1, and O states (PDB 8E4P, 8E4N, and 8E4L, respectively) are used for illustration. (B) Chemical structures of TC-I 2014, AMG2850, and AMTB. (C) 3D reconstructions of the conformation A (left; brown) and the C0 state (right; silver-gray). Neighboring protomers are colored in gray. (D) TMD comparison between the conformation A (left; brown) and the C0 state (right; silver-gray). S2-S3 linkers and S3 were omitted for clarity. (E and F) EM density at the VSLD cavity (E) and the S4-S5 linker (F) from the conformation A reconstruction in (C). Densities corresponding to antagonists are colored in lime for TC-I, teal for AMG, and blue for AMTB. Red dashed circles indicate the lack of antagonist densities. Thresholding 0.3 in (E) and 0.6 in (F). (G and I) Binding site and EM densities for TC-I [(G) left, lime sticks], AMG [(G) right, teal sticks], and AMTB [(I) blue sticks]. Densities in magenta mesh are contoured at thresholding 0.3 for TC-I, 0.34 for AMG, and 0.2 for AMTB. (H and J) Summary of current inhibition by 10 μM TC-I or 10 μM AMG (H) or by 25 μM AMTB (J) measured by TEVC recording on the WT and mutant TRPM8MM channels activated by 10 to 30 μM C3 at −60 mV. The antagonist inhibition level is quantified by the percentage of current inhibited by antagonists over full inhibition by 50 μM RR (see Materials and Methods). Values for individual oocytes are shown as open circles with means ± SEM (n = 3 to 8 oocytes). ns > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Prolonged or recurring exposure to cold or menthol leads to sensory adaption (12–14), which arises from reduced TRPM8 activity whereby the channel currents decline in a manner dependent on extracellular Ca2+ (13–17). This “desensitization” of TRPM8 substantially shapes our perception of cold, yet its mechanism is largely unclear (Fig. 1A). There are five major barriers to our understanding. First, the conformational changes and key structural determinants leading to the desensitized (D) state are not yet known. Second, the physiologically relevant D conformation has not been established through functional studies. While a Ca2+-bound avian TRPM8 (Parus major; TRPM8PM) structure was suggested as a D state (18), a similar conformation of TRPM8MM was observed in the absence of Ca2+ and proposed as a closed state (19). However, neither study tested the functional relevance of these conformations. Third, TRPM8 can be activated by various chemical or physical cooling stimuli, but it is unknown if TRPM8 undergoes shared or separate pathways toward desensitization. Fourth, it is unclear how the D state fits into the gating landscape. Last, the role of PIP2 in desensitization has been debated—several studies suggest that Ca2+ influx through activated TRPM8 channels activates phospholipase C (PLC), thereby depleting PIP2 and inhibiting TRPM8 activity (7, 20, 21). In contrast, a 2019 study of TRPM8PM proposed that channel desensitization is mediated by direct Ca2+ binding, not by PIP2 depletion (18).

On the other hand, TRPM8 has been linked to various pathological conditions, including the recent genome-wide association studies revealing its association with a reduced risk of migraine (22, 23). Antagonism against TRPM8 has thus emerged as a promising strategy for treating cold-associated pain disorders, bladder sensory disorders, and migraine. Demonstrably, TRPM8 antagonists (Fig. 1B) have shown efficacy against in vivo models of cold allodynia, cold hypersensitivity (24–32), and bladder hypersensitivity (27, 33, 34). Therefore, understanding the mechanisms by which these antagonists inhibit TRPM8 is crucial for therapeutic advancements. Previous cryo-EM structures of TRPM8PM determined in the presence of antagonists TC-I 2014 and AMTB suggested overlapping binding sites for type I agonists and antagonists, respectively, indicating that the antagonists stabilize a closed state (18). However, the suboptimal EM density quality for the ligands and lack of functional validation of the binding sites have raised concerns for mechanistic interpretation. Moreover, recent structural studies of a mammalian TRPM8 have revealed three distinct nonconducting conformations (C0, C1, and C2), defined by distinct residues comprising the S6 gate of the pore (Fig. 1A) (10). It remains unclear which nonconducting conformational state TRPM8 antagonists stabilize and if they do so in a state-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Our study investigates the underlying mechanisms and interrelatedness of TRPM8 desensitization and inhibition, shedding light on cold adaptation in animals and drug development in humans (Fig. 1A).

RESULTS

Cryo-EM analysis reveals a distinct channel conformation in complex with TRPM8 antagonists

TC-I 2014, AMG2850, and AMTB hydrochloride (abbreviated as TC-I, AMG, and AMTB, respectively, hereafter) are representative TRPM8 antagonists with distinct molecular scaffolds (Fig. 1B). They exhibit selective and potent TRPM8 antagonism in in vitro functional assays and in vivo models of inflammatory or neuropathic pain (32, 33, 35, 36). We purified TRPM8MM channels in detergents lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG) and cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS). We previously found that PIP2 is copurified with TRPM8MM in detergents, resulting in the C1-state channel conformation, and that the inclusion of CHS during purification effectively displaces PIP2 from TRPM8MM (10). In the absence of antagonists and PIP2, the apo dataset yielded two three-dimensional (3D) classes with distinct nonconducting channel conformations—one adopts the C0 ground state, which proceeds to the C1 state in the presence of PIP2 (10), while the other conformation is distinct from the closed C0, C1, and C2 conformations but is similar to the published TRPM8MM (19) and Ca2+-bound TRPM8PM structures (Fig. 1, A and C, and fig. S2A) (18). We tentatively assigned this functionally nonvalidated conformation as “conformation A.” In the C0-state conformation, the C-terminal part of S4 (termed S4b) is α-helical and S5 is a long and straight helix; in conformation A, part of S4b is 310-helical and part of S5 bends to form the S4-S5 linker (Fig. 1D). Notably, for the antagonist-treated cryo-EM samples, a strong and unambiguous EM density corresponding to the antagonist was identified in the conformation A reconstruction (Fig. 1, E and F, and figs. S2, B to D, and S3). These structures of TRPM8MM in complex with TC-I, AMG, and AMTB, respectively, were refined to overall resolutions of 2.81 to 3.42 Å (figs. S4 and S5, and table S1).

More notably, we found that EM densities corresponding to TC-I and AMG are located at a previously unknown ligand-binding site in TRPM8 channels—an intersubunit interface above the S4-S5 linker, whereas the density for AMTB resides within the voltage-sensor–like domain (VSLD) cavity, overlapping with the type I cooling agonists (Fig. 1, E and F). The local resolution at the TMD was estimated to be 2.5 to 3 Å for all the 3D reconstructions in conformation A, which enabled us to unambiguously model all three antagonists and the surrounding protein side chains (fig. S5). We refer to the ligand-free and antagonist-bound conformation A reconstructions as TRPM8MM_apo, TRPM8MM_TC-I, TRPM8MM_AMG, and TRPM8MM_AMTB, respectively.

To corroborate this previously unknown binding site for TC-I and AMG, which is distinct from the type I agonist site within the VSLD cavity, we determined the structure of TRPM8MM in the presence of both the type I agonist cryosim-3 (C3) and TC-I (referred to as TRPM8MM_TC-I+C3) to a 2.76-Å resolution (fig. S2E). Clear EM densities corresponding to C3 in the VSLD cavity and TC-I at the S4-S5 linker were identified in the conformation A class (fig. S5H). We have therefore revealed two antagonist binding sites in mouse TRPM8—one above the S4-S5 linker and the other within the VSLD cavity. Antagonist binding to either location is specific to the TRPM8 channel in conformation A.

Structures provide the molecular basis of antagonist binding in mouse TRPM8

The ligand-binding site for TC-I and AMG is located at an intersubunit interface formed by S4, the S4-S5 linker, and S5 and S6 of the neighboring pore domain (denoted as S5′ and S6′, respectively) (Fig. 1G). Nonpolar residues on the S4-S5 linker, including Leu860 and Met863, accommodate the core hydrophobic groups in TC-I and AMG. TC-I binding is stabilized by two hydrogen bonds with Trp877 on S5′ and Ser966 on S6′ while AMG only hydrogen bonds with Trp877. The Trp877Ala mutation reduced the inhibitor potency of both TC-I and AMG, while Ser966Ala only reduced inhibition by TC-I (Fig. 1H and fig. S6, B and C). For AMTB, the binding site partially overlaps with that for the type I agonist in the VSLD cavity (Fig. 1I). Here, the primary amine group in AMTB forms a hydrogen bond with Glu782, Tyr793, and Asn799 on S2, the S2-S3 linker, and S3, respectively, mimicking Ca2+ binding in TRPM8 (fig. S6A). Mutations Glu782Gln, Tyr793Ala, and Asn799Ala reduced channel inhibition by AMTB, while Trp877Ala and Ser966Ala retained the inhibition by AMTB (Fig. 1J and fig. S6D). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations further validated the antagonist binding sites. In 12 simulation replicates (~500 ns each), all three antagonists showed stable binding with low degrees of root mean square deviation (RMSD) displacements (fig. S7, A to C) (37). These results together support that the binding site for TC-I and AMG is distinct from that for AMTB.

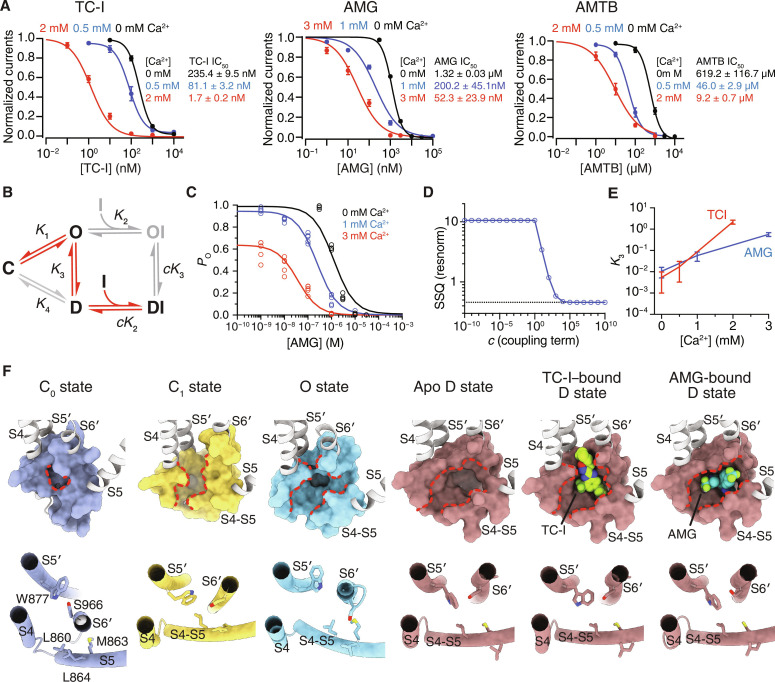

Thermodynamic modeling defines the D-state conformation of TRPM8

On the basis of the conformation A–specific binding of antagonists in TRPM8 channels in our structural analysis, we asked two fundamental questions: (i) Which physiologically relevant functional state does the conformation A represent for TRPM8 channels? (ii) Does the antagonist act on the conformation A state of TRPM8 via an induced fit or a conformation selection mechanism? It has been shown that TRPM8 desensitization is Ca2+-dependent (13–17), so the presence of elevated extracellular Ca2+ concentrations should shift the channel gating equilibrium toward desensitization. In our two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) experiments, when the extracellular Ca2+ was increased from 0 to 2 or 3 mM, we observed not only greater channel desensitization but also increased inhibition potency by ~138-fold, ~25-fold, and ~67-fold for TC-I, AMG, and AMTB, respectively. This suggests that antagonists bind preferentially to the D state of TRPM8 (Fig. 2A and fig. S6, E to G).

Fig. 2. Molecular details of state-dependent inhibition.

(A) Mean normalized concentration-response relations for TC-I (left), AMG (middle), and AMTB (right) against TRPM8MM activation by 1 mM menthol in the presence of increasing concentrations of extracellular Ca2+ in the TEVC recording buffer. Data are shown as means ± SEM. n = 4, 5, and 4 oocytes for measurement with 0, 0.5, and 2 mM Ca2+ in the left panel, respectively; n = 4, 5, and 5 oocytes for measurement with 0, 1, and 3 mM Ca2+ in the middle panel, respectively; n = 5, 5, and 6 oocytes for measurement with 0, 0.5, and 2 mM Ca2+ in the right panel, respectively. The continuous curves were fit to the Hill equation with IC50 values indicated in the figure. (B) Thermodynamic model of TRPM8 desensitization and inhibitor binding for the equilibria (Kn) among C, O, D, OI, and DI states and the associated thermodynamic coupling (c). Red arrows indicate transition among the thermodynamically favored states based on fit values. (C) AMG dose-response data fit with the thermodynamic model for 0, 1, and 3 mM extracellular Ca2+. Data are from (A), taking into account the initial level of desensitization. Data points for individual replicate (n ≥ 4) shown. (D) Model fit quality as SSQ plotted as a function of fixed coupling parameter (c) value. (E) Calcium dependence of desensitization (K3) for AMG and TC-I. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (F) Shown in surface (upper) and cylinder (lower) representations, comparison of the antagonist binding site above the S4-S5 linker in TRPM8 channels adopting the C0 (PDB 8E4P), C1 (PDB 8E4N), O (PDB 8E4L), and D (current study) states. Red dashed lines highlight changes in the size of the binding pocket. TC-I and AMG shown as spheres, and residues involved in antagonist binding shown as sticks.

Because we observed that antagonists bind preferentially to conformation A, not to the C0 state, we hypothesized that conformation A may therefore represent the D state. To test this, we applied thermodynamic analysis to the Ca2+-dependent change in the median inhibitory concentration (IC50) of TC-I and AMG against channel activation by menthol, taking into account the initial proportion of channel desensitization induced by extracellular Ca2+ addition (Fig. 2A and fig. S6, E to G). We proposed a simplified model for TRPM8 channel gating and antagonist binding (Fig. 2B and fig. S8A; Materials and Methods). On the basis of the steady-state currents from the electrophysiological recordings, we modeled the apparent probability (PO) of the O-state channels [O and inhibitor-bound open (OI)] with respect to antagonist concentrations at three different Ca2+ concentrations (zero, low, and high) (Fig. 2, C and D, fig. S8, B and C). We fit the forward equilibrium constants for inhibitor binding and desensitization (K2 and K3, respectively) and a thermodynamic parameter (c) for the coupling between these two processes (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 2E and fig. S8D). Higher Ca2+ concentrations gave rise to increased K3 and shifted the equilibria toward the D states (Fig. 2E and fig. S8, E and F). Notably, fitting revealed that the coupling term (c) must be ≥104, indicating very strong positive coupling between desensitization and inhibitor binding (Fig. 2D and fig. S8C). Thus, relative to K2 (O⇌OI), the greater equilibrium constant cK2, which governs the forward process in D⇌DI, indicates that antagonist binding is much more favorable to the D state and follows a conformational selection mechanism (channel desensitization occurs first, followed by antagonist binding) rather than an induced fit mechanism (antagonist binding to the O state triggers channel rearrangement to the D state). This favorable shift in D→DI due to antagonist binding, in turn, drives the conformational propensity from channel opening toward desensitization (O→D) (fig. S8, E and F; see the section Structural and functional analyses reveal the structural determinants for TRPM8 desensitization and inhibition). The thermodynamic modeling result supports our structural and electrophysiological findings: (i) the conformation of our antagonist-bound structures (conformation A) represents the D functional state of TRPM8; and (ii) antagonists bind to and specifically stabilize the D-state channel. Moreover, comparison at the antagonist binding site of TRPM8 structures of functionally distinct states suggests that the intersubunit cavity can accommodate binding of TC-I and AMG only when the TMD adopts the D-state conformation but not the C0, C1, or O states (Fig. 2F). Substantial helical rotation (~90° to 180°) and register change in S6 during ligand-dependent channel gating ensure that the antagonist-binding residues are only optimally oriented toward the cavity in the D state. Together, our structural, functional, and thermodynamic modeling analyses show that TRPM8 desensitization and inhibition exhibit overlapping mechanisms. Therefore, these inhibitors are excellent tools to probe the D-state conformation of TRPM8.

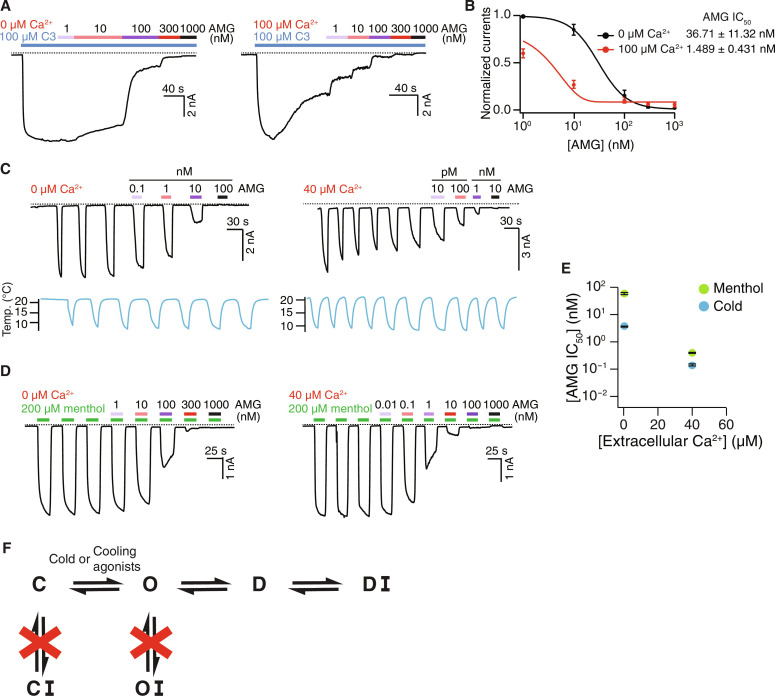

TRPM8 activation by cold and chemical stimuli converges on a shared D state

While it is well known that the heat and capsaicin sensor TRPV1 adopts stimuli-specific gating pathways (38–40), similar knowledge is lacking for TRPM8. Particularly, it remains unclear if TRPM8 uses shared or separate desensitization pathways in response to distinct physical and chemical cooling stimuli.

We leverage the D-state selective antagonists to probe sensory adaptation mediated by the TRPM8 channel in response to various stimuli. First, C3-activated TRPM8 currents exhibit Ca2+-dependent desensitization, and inhibition potency of AMG is increased in a desensitization-dependent manner (Fig. 3, A and B), similar to menthol-activated TRPM8 (Fig. 2A). Next, cold-evoked TRPM8 currents desensitize and adapt in a Ca2+-dependent manner after repeated stimulation (Fig. 3C) (13, 17). We used a repeated cold stimulation protocol because prolonged cold treatment alone slightly desensitizes TRPM8. We found that increasing extracellular Ca2+ potentiated the inhibition potency of AMG regardless of channel activation through repeated cooling or applications of menthol (Fig. 3, C to E). Notably, AMG exhibits a higher apparent affinity for TRPM8 activated by cold than by menthol (Fig. 3E and fig. S9) (36). These results suggest that the D state of TRPM8 is independent of the mode of channel activation by either cold or chemical stimuli. In particular, with little or no structural information available for the cold-dependent gating of TRPM8 at present, our data show that the cold-induced D state adopts a conformation similar to that induced by chemical agonists.

Fig. 3. TRPM8 activation by distinct stimuli converges on desensitization.

(A) Representative whole-cell recordings on HEK293T cells expressing the WT TRPM8MM channels at −60 mV. Current trace elicited by 100 μM C3 was inhibited by increasing concentrations of AMG in the presence of 0 μM (left) and 100 μM (right) extracellular Ca2+. (B) Mean normalized concentration-response relations for AMG against the WT TRPM8MM activation by 100 μM C3 in the presence of 0 μM (black trace; n = 5) or 100 μM (red trace; n = 4) extracellular Ca2+. Data are means ± SEM. The continuous curves were fit to the Hill equation with IC50 values indicated in the figure. (C and D) Representative whole-cell recordings on HEK293T cells expressing the WT TRPM8MM channels at −60 mV. Current trace elicited by cold (C) or 200 μM menthol (D) was inhibited by increasing concentrations of AMG in the presence of 0 μM (left) or 40 μM (right) extracellular Ca2+. Currents were first stabilized after three to six repeated cold or menthol activations, then increasing concentrations of AMG were coapplied with subsequent cold or menthol pulses, as indicated. (E) Summary of IC50 values for WT TRPM8MM activation by cold (blue circles) and menthol (green circles) in the presence of 0 and 40 μM extracellular Ca2+ (n = 3 to 4). Data are means ± SEM. The continuous curves fit to the Hill equation with IC50 values are in fig. S9. (F) Simplified schematic diagram showing the TRPM8 gating pathway from the C to the O state followed by D and DI with antagonist bound. Dashed lines in (A), (C), and (D) indicate the zero-current level.

Together, our results suggest that the conformational landscapes for TRPM8 activation by cold and various chemical stimuli converge on a shared D state, which shows both Ca2+ dependence and conformational specificity for antagonist binding (Fig. 3F).

D state–specific antagonism is conserved in avian TRPM8

The antagonist binding sites revealed in the current study are in stark contrast with the published TRPM8PM structures in which TC-I and AMTB were modeled as binding to the VSLD cavity (fig. S10) (18). First, both TRPM8PM_TC-I and TRPM8PM_AMTB adopt a C0-state conformation (18), contrary to our findings that all three antagonists preferentially bind to TRPM8MM in the D-state conformation (fig. S10, A and B). Second, both TC-I and AMTB are modeled as bound to the VSLD cavity in TRPM8PM, sharing a common binding site with the type I agonists such as menthol and icilin; while in TRPM8MM, TC-I and AMG bind to a previously unidentified binding site above the S4-S5 linker and AMTB binds to the VSLD cavity of the D-state channel. Third, TC-I and AMTB exhibit distinct binding sites and poses between the previously published TRPM8PM and our TRPM8MM structures, respectively (fig. S10, C and D). The cryo-EM maps of the ligand-free TRPM8PM, TRPM8PM_TC-I, and TRPM8PM_AMTB all contain similarly shaped EM density peaks in the VSLD cavity, rendering the assignments of TC-I and AMTB in TRPM8PM questionable (fig. S10, E and F). No functional experiments were conducted previously to validate the antagonist binding sites in TRPM8PM.

We sought to address the discrepancy in the results between our current study on TRPM8MM and the prior work on the avian TRPM8PM. First, we determined a cryo-EM structure of the wild-type (WT) TRPM8PM in complex with TC-I to a 3.26-Å resolution (figs. S11A and S12). Consistent with what we observed in the TRPM8MM channel, a strong and unambiguous EM density corresponding to TC-I was identified exclusively at the intersubunit interface above the S4-S5 linker, specifically in the D-state channel conformation (fig. S11B). TC-I binding is mediated by interactions with the conserved residues Trp883 on S5′ and Ser972 on S6′ in TRPM8PM (fig. S11C). Mutagenesis at this site—Trp883Ala and Ser972Ala in TRPM8PM as well as Trp876Ala and Ser965Ala in the avian collared flycatcher TRPM8 channel (TRPM8FA)—but not at the VSLD cavity site (Phe845Leu or Phe845Ala in TRPM8PM and Phe838Leu or Phe838Ala in TRPM8FA) significantly reduced channel inhibition by TC-I (fig. S11, D and E), which is consistent with the data for TRPM8MM (Fig. 1H).

To address AMTB binding to TRPM8PM, mutations Glu792Gln (a Ca2+-coordinating site) and Tyr800Ala (on S2-S3) in TRPM8PM affect channel inhibition by AMTB, which is similar to the mutational effects of the equivalent residues on TRPM8MM (fig. S11F and Fig. 1J). Sequence alignment indicates that the key residues at the binding sites for TC-I/AMG and AMTB are fully conserved between mammalian and avian TRPM8 orthologs (fig. S13). Consistently, in MD simulations, AMTB modeled as in the published TRPM8PM exhibits substantially larger RMSD displacement (~4.9 Å) than that of TRPM8MM (~2.5 Å) (fig. S7, C and E); the primary amine group in AMTB universally reorients toward Glu792 and Tyr800 after simulation (fig. S7, F and G). Most importantly, we found that the increase in the extracellular Ca2+ concentration substantially enhanced the IC50 of TC-I, AMG, and AMTB against the TRPM8PM channel (fig. S11, G to L), suggesting a desensitization-dependent inhibition (DI) in TRPM8PM which is consistent with that of TRPM8MM.

Together, our studies unambiguously show that the antagonist binding sites and the mechanism of channel inhibition are conserved between avian and mammalian TRPM8 channels.

Structural and functional analyses reveal the structural determinants for TRPM8 desensitization and inhibition

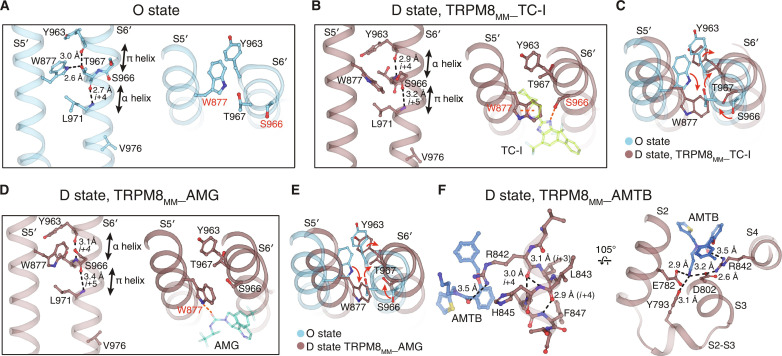

The previous attempt to interpret the structural basis of desensitization was limited to the comparison of the C0 and D states of an avian TRPM8 (18). Because Ca2+ influx through open TRPM8 is crucial for TRPM8 desensitization (7, 13, 14, 17, 21), TRPM8 desensitization must follow channel activation in a physiological setting (Fig. 2B). Therefore, comparison of the O state and the D state structures [Protein Data Bank (PDB) 8E4L and TRPM8MM_TC-I, respectively] provides valuable insights into the conformational change of TRPM8 desensitization. When the TMDs of the O and the D state structures are aligned, the pore domain (including the S4-S5 linker, S5, and S6) rotates toward the central axis of the channel as the channel transitions from the O to the D state (Fig. 4A). S6 translates downward by one helical turn, and the π helix position (41) changes by one helical turn from residues Tyr963-Thr967 in the O state to Thr967-Leu971 in the D state (fig. S14A). When the channel desensitizes, the upper pore domain, including the selectivity filter, dilates, while the S6 gate is constricted by Val976—the same gating residue as in the O state (Fig. 4, B and C, and fig. S14B). Also, during channel desensitization, the cytoplasmic MHR4 domain decouples and rotates clockwise away from the TMD, exhibiting global conformational changes (fig. S14C).

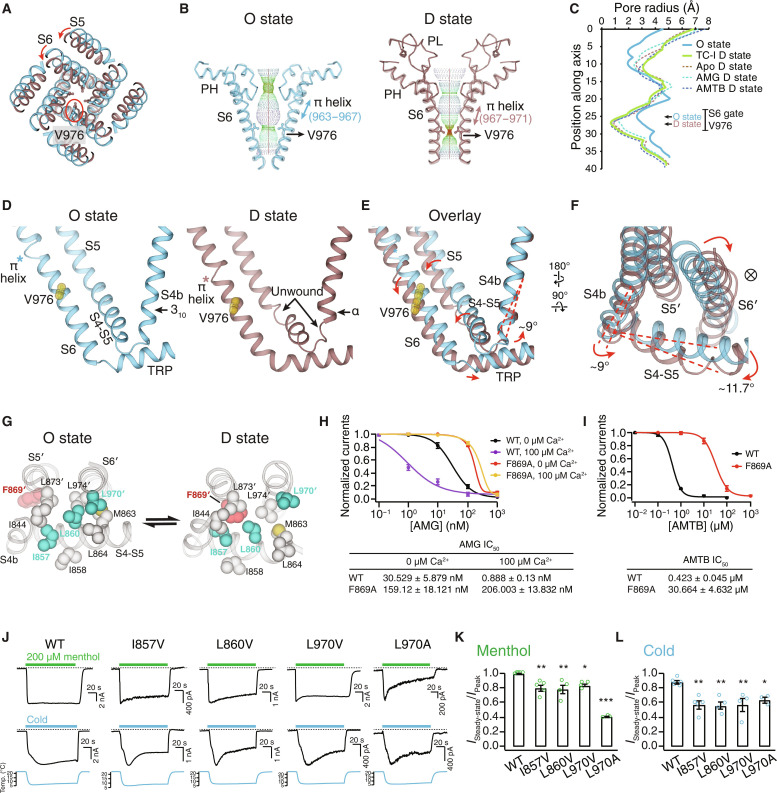

Fig. 4. Mechanism of TRPM8 desensitization.

(A) Aligned at the VSLD, comparison of the O (blue) the D (brown) states at the pore, viewed from the extracellular side. Red circle indicates the S6 gate residue Val976. (B and C) Ion permeation pathway (B) and pore radii (C) in the O state and the D state. (D to F) Comparison of the O and the D states at the interfacial cavity for PIP2 binding [(D) and (E)] and at S4b and the S4-S5 linker (F). Val976 shown as yellow spheres. Asterisks denote the π helix position. Red dashed lines and arrows in (E) indicate the structural rearrangements from the O to the D state. ⊗ symbol denotes the ion conduction pathway. (G) Comparison of the O and the D states at the interaction network among S4, the S4-S5 linker, and the neighboring pore domain (S5′ and S6′) with Phe869′ highlighted in red and Ile857, Leu860, and Leu970′ in teal. (H) Mean normalized concentration-response relations for AMG against the WT (n = 3) and F869A (n = 3) in the presence of 0 or 100 μM extracellular Ca2+. Representative current traces shown in fig. S14E. (I) Mean normalized concentration-response relations for AMTB against the WT (black trace; n = 3) and F869A (red trace; n = 3). Representative current traces shown in fig. S14F. (J) Representative current traces of the WT and mutant TRPM8MM channels activated by 200 μM menthol (upper) and cold (lower) at −60 mV in HEK293T cells. Dashed lines indicate the zero-current level. (K and L) Summary of currents remaining after desensitization for the WT and mutant TRPM8MM channels activated by menthol (K) and cold (L) (n = 3 to 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Data are means ± SEM in (H), (I), (K), and (L).

The drastic pore domain rearrangement during channel desensitization is mediated and propagated from the local structural changes at S4b and the S4-S5 linker. In the D state, the N and C termini of the S4-S5 linker unwind into coils and the last helical turn in S4b transitions from 310 to α helix and rotates by 9° to 10° relative to the O-state conformation (Fig. 4, D to F, and fig. S14D). In particular, these changes lead to the downward rotation of the S4-S5 linker by 12°, which decouples the VSLD, the pore domain, and the TRP domain (Fig. 4, E and F). As a result, the pore domain (S5′ and S6′) relocates closer to the central channel axis, the ion conduction pathway narrows, and the S6 gate closes (Fig. 4F). Thus, the S4-S5 linker motion appears critical for desensitization.

A closer comparison between the O and the D states reveals that the S4-S5 linker forms hydrophobic interaction networks with the neighboring pore domain (S5′ and S6′) in a state-dependent manner. Central to this desensitization-associated structural rearrangement is Phe869 on S5′, which is located away from this network in the O state but joins the network only in the D state, likely contributing to the D-state stabilization (Fig. 4G). We hypothesized that mutation of Phe869 will disrupt the network, thereby destabilizing the D state. Consistent with our hypothesis, Phe869Ala reduces the potency of the D state–specific antagonist AMG by more than fivefold in the absence of Ca2+ and 230-fold in the presence of 0.1 mM Ca2+. It also reduces the potency of AMTB by more than 70-fold in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 4, H and I, and fig. S14, E and F). In the O state, the S4-S5 linker, together with S5′ and S6′, forms an alternate but tighter hydrophobic network. Mutations of residues participating in this O-state network (Ile857Val and Leu860Val on S4-S5 and Leu970Val on S6′) enhance desensitization in response to cold or menthol in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, indicating the importance of the hydrophobic interaction network of the S4-S5 linker in desensitization (Fig. 4, J to L, and fig. S14, G and H).

This finding further supports the important role of the S4-S5 linker in channel activation and desensitization, achieved by coupling and decoupling the VSLD and the pore domain, respectively.

TRPM8 antagonists function by stabilizing the D-state channel conformation at the pore domain (S5 and S6) or S4b in the VSLD cavity (Fig. 5). TC-I and AMG binding engages residues Trp877 and Ser966 on the pore domain (S5′ and S6′), which locks the π helix backbone at Ser966-Leu971 in the D-state conformation after the S6 π-helical rearrangement from the O state (Fig. 5, A to E). AMTB binding within the VSLD cavity stabilizes S4b and S2-S3 in the D-state conformation through direct interactions (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5. Mechanism of TRPM8 inhibition.

(A to E) Comparison of the pore domain (S5′ and S6′) between the O (A) and the D states [(B) and (D)]. Trp877 on S5 is rotated and exposed to the membrane-facing side, and the π helix position on S6 is shifted in the D state [(C) and (E)]. TC-I or AMG binding stabilizes the alternate π helix and the rotated Trp877 positions in the D state [(B) and (D)]. Dashed lines indicate interactions that stabilize the specific helical configurations. (F) AMTB interaction stabilizes the VSLD in the D state. Residue side chains and antagonists shown as sticks.

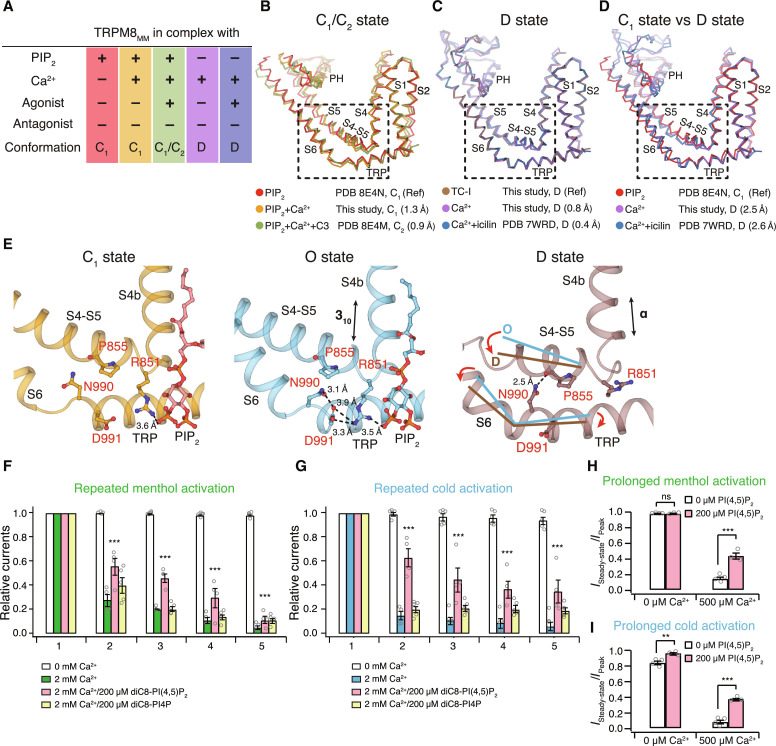

TRPM8 desensitization requires both PIP2 depletion and Ca2+ binding

Our thermodynamic modeling (Fig. 2B) and structural analyses (Fig. 4) elucidate the conformational changes of TRPM8 desensitization that follows activation. Activated channel raises the intracellular concentration of Ca2+, which thus induces channel desensitization in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Fig. 3). High cytosolic Ca2+ triggers the downstream Ca2+-dependent PLC pathway that hydrolyzes PIP2 in the plasma membrane, thereby depleting it from TRPM8 channels (7, 21); on the other hand, cytosolic Ca2+ also directly binds to a conserved site in the VSLD cavity (18). Whether channel desensitization is driven by PIP2 depletion from TRPM8 (7, 21) or by the binding of Ca2+ to the VSLD cavity (18) is a debated and controversial matter. Therefore, we set out to verify the role of these two mechanisms in TRPM8 desensitization by structural and functional analyses.

We determined TRPM8MM structures in complex with both Ca2+ and PIP2 (termed TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+) and in the absence of PIP2 but the presence of Ca2+ (TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+) (fig. S15). PIP2 binds to an interfacial cavity formed by MHR4, pre-S1 domain, S4-S5, and the TRP domain (8, 10, 11, 42). The EM density corresponding to PIP2 was resolved in TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+ but not in TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+ (fig. S16A). The VSLD cavity of both structures exhibits an EM density peak between S2 and S3 consistent with a Ca2+ ion coordinated by Glu782, Gln785 on S2 and Asn799, Asp802 on S3, as observed in previous structures (fig. S16A). Together with the published TRPM8MM structures (10, 19), (i) in complex with PIP2 only (TRPM8MM_PIP2; PDB 8E4N); (ii) in complex with PIP2, Ca2+, and agonist C3 (TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2++C3; PDB 8E4M); (iii) in the absence of PIP2 but in complex with Ca2+ and agonist icilin (TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2++icilin; PDB 7WRD), we compared the channel conformations and analyzed structural changes induced by PIP2 removal and/or Ca2+ binding (Fig. 6, A to D).

Fig. 6. Roles of PIP2 and Ca2+ in TRPM8 desensitization.

(A) Table of channel conformation and ligands present for five TRPM8MM structures used for analyses in (B) to (D). (B to D) TMD superimposition among structures as indicated. Channel structures shown as ribbons and colored as in (A). Dashed boxes highlighting conformations at S4b, S4-S5, S6, and the TRP domain (residues 839 to 877 and 966 to 999). Cα RMSD values at this region against the reference structure (Ref) are indicated in parentheses. PDB IDs or structures from the current study and the corresponding channel conformation are specified. (E) Comparison of interactions between the S4-S5 linker and the TRP domain in the PIP2-bound C1 state (left, orange; PDB 8E4N), the O state (middle, blue; PDB 8E4L), and the D state (right, brown; TRPM8MM_TC-I). PIP2 shown as red sticks and key residues shown as sticks and labeled in red. Dashed lines indicate residue interactions. Secondary structural change at S4b and movements at the S4-S5 linker and S6-TRP are indicated by arrows. (F and G) Summary of normalized currents of the TRPM8MM channel upon repeated activation by menthol (F) and cold (G) (n = 4 to 5) at −60 mV. Open circles indicate the individual data points for each experiment. ***P < 0.001, using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post hoc test. Representative time courses shown in fig. S16 [(B) to (E)]. (H and I) Summary of currents remained after desensitization of the TRPM8MM channel subject to prolonged activation by menthol (H) and cold (I) (n = 3 to 4). Open circles indicate the individual data points for each experiment. ns > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post hoc test. Representative time courses shown in fig. S16 [(F) and (G)]. Data are means ± SEM in (F) to (I).

TRPM8MM_PIP2 represents the more physiologically relevant ground state (closed C1 state) of TRPM8 with PIP2 bound in the absence of agonists and Ca2+. In the presence of PIP2, the binding of agonist C3 and Ca2+ (TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2++C3) or Ca2+ alone (TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+) induces local changes at the binding site within the VSLD cavity, while the conformation of the pore domain remains the same as C1 (Fig. 6B). This suggests that, in the presence of PIP2, Ca2+ binding directly to the VSLD does not convert TRPM8 into the D state. In stark contrast, when PIP2 is absent in the channel, the addition of Ca2+ alone (TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+) or both Ca2+ and agonist icilin (TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2++icilin) converts the channel into a conformation resembling the antagonist-bound D state (Fig. 6C) but distinct from the PIP2-bound structures in the C1 state (Fig. 6D). This suggests that both PIP2 removal and Ca2+ binding are required for TRPM8 desensitization.

Next, we asked, what role does PIP2 play in TRPM8 desensitization? In the PIP2-bound O- and C1-state conformations, PIP2 interacts with the S4-S5 linker, S4b, and the TRP domain, thereby maintaining the coupling of the S4-S5 linker with S6 and the TRP domain (Fig. 6E). Notably, this PIP2-mediated interaction network is more extensive in the O state, including Arg851 (S4-S5 linker), Asn990 (S6), and Asp991 (TRP domain). The absence of PIP2 “collapses” the interfacial cavity in the D-state conformation, thus allowing for rearrangement of the S4-S5 linker and S4b, effectively decoupling the VSLD from the pore (Fig. 6E). Consistent with our structural analyses, whole-cell patch clamp recordings of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells expressing TRPM8MM show that inclusion of 200 μM dioctanoyl (diC8)-PI(4,5)P2, but not diC8-PI4P, in the patch pipette effectively mitigates desensitization of channel currents activated by either repeated or prolonged cooling stimuli (menthol or cold) (Fig. 6, F to I, and fig. S16, B to G). Similar observations were made in native dorsal root ganglion neurons expressing TRPM8 (43). Together, our structural and functional analyses corroborate and strengthen the essential role of PIP2 in Ca2+-mediated desensitization.

DISCUSSION

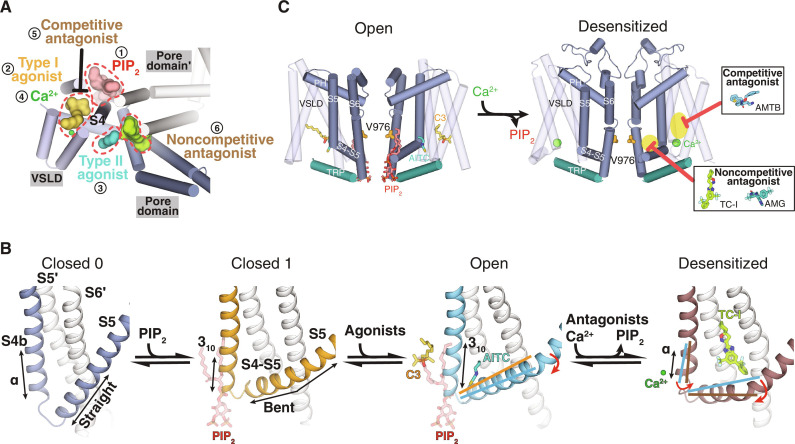

Our structural, functional, and thermodynamic modeling studies show that TRPM8 desensitization to prolonged cooling stimuli and inhibition by chemical antagonists occur through an overlapping mechanism—the channel desensitizes upon channel activation followed by PIP2 depletion and Ca2+ binding, while the extant TRPM8 antagonists exert inhibitory effects by specifically stabilizing the D state.

Both TRPM8 agonists and antagonists have potential therapeutic applications. We have now found the binding sites for a wide range of essential channel modulators, including PIP2, type I and type II agonists, Ca2+, and both competitive and noncompetitive antagonists (Fig. 7A and fig. S17A). These binding sites are all clustered at the junction between the VSLD cavity and the pore domain, a region mediated by the S4 helix and the connecting S4-S5 linker. Binding of these modulators leads to local conformational changes in S4b and the S4-S5 linker, which are propagated to the pore of TRPM8, leading to channel activation or desensitization. Specifically, the binding of the type I agonists, PIP2, and Ca2+ triggers conformational changes in S4b, which, in turn, change the conformation of the S4-S5 linker. Therefore, the S4-S5 linker conformation is the key determinant for TRPM8 gating. This explains why antagonists that bind to the S4-S5 linker exhibit strong conformational selectivity. The binding of PIP2 engages a more comprehensive network, including S4b, the S4-S5 linker, the TRP domain, and the cytosolic MHR4 domain, which is why PIP2 plays the role of priming the channel for activation and protecting it against desensitization. The combination of these modulators generates unique conformational poses of S4b and the S4-S5 linker, including the angle between them and their secondary structures, which control channel gating processes such as activation and desensitization (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Summary of ligand binding and ligand-dependent gating of TRPM8 channels.

(A) The binding sites for PIP2 (1), type I agonists (2), type II agonists (3), Ca2+ ions (4), competitive antagonists (5), and noncompetitive agonists (6) are located surrounding the S4b in TRPM8. Representative ligands, PIP2 (red), C3 (yellow), AITC (teal), TC-I (lime), and Ca2+ (green), are shown in surface or sphere and highlighted by dashed lines. (B) Conformational changes of S4b, S5, and the S4-S5 linker in the closed C0 (silver-gray), closed C1 (yellow), O (blue), and D (brown) states. Secondary structures and S4-S5 linker motions indicated by lines and arrows. PIP2, C3, AITC, and TC-I shown as sticks and Ca2+ ions as spheres. Neighboring protomers colored in white. (C) Structural diagram illustrating the conformational change from the O state to the D state and the D state–dependent inhibition by antagonists. Ligands and S6 gate residue Val976 shown as sticks and Ca2+ as green spheres. Insets show antagonist binding highlighted in yellow shades and red arrows.

In contrast to the capsaicin- and heat-sensing TRPV1 channel, in which agonists, antagonists, and lipid modulators bind to a common site at the S4-S5 linker (fig. S17, B and C) (44, 45), the diverse yet localized ligand-binding sites in TRPM8 allow for multiplex allosteric regulation of channel functions. Our studies have therefore provided comprehensive knowledge on the interplay among diverse TRPM8 modulators, which will advance rational drug design for treatment of various diseases. For example, our results underscore the importance of using the D-state TRPM8MM structure specifically for future antagonist development.

In this study, we found that TRPM8 antagonists bind to and inhibit the channel specifically in the D state (Fig. 7C). This conformation selection feature of antagonist binding enabled us to functionally demonstrate that the cold-adapted channel adopts a conformation resembling the D state following cooling agonist activation. Physiological adaptions to cold and cooling agonists (menthol) therefore converge on a common state along the conformational landscape of TRPM8 gating. The observation that the degree of desensitization is stimulus-dependent (cold versus cooling agonists) is due to stimuli-dependent differences in channel conformational propensities for C, O, and D states (Fig. 3, E and F). This illustrates how modulation of receptor-level conformational ensembles can alter our sensation of cold and contribute to cold-associated pain. Together, our work provides a comprehensive mechanistic understanding of the ligand-dependent TRPM8 gating pathway by incorporating desensitization and inhibition into the scheme. We demonstrate how the cold and menthol sensor, TRPM8, serves as an excellent example for investigating sensory adaptation—changes in our perception of the cooling environment are mediated by the conformational rearrangements from the O to the D state of TRPM8 channels—and how such feature can be leveraged for therapeutics development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

The full-length WT mouse Trpm8 (Trpm8MM) cDNA sequence was subcloned into a modified pEG BacMam vector (46) in frame with a C-terminal PreScission protease cleavage site followed by a FLAG tag and a 10x His tag. TRPM8MM channels were expressed following the same procedures from a published study (10). Protein purification was carried out at 4°C.

To determine the TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+ and TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+ structures, HEK293F cells expressing TRPM8MM were resuspended in buffer A [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, leupeptin (12 μg mL−1), pepstatin (12 μg mL−1), aprotinin (12 μg mL−1), 1.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I] and lysed by a Dounce tissue grinder. 1% glyco-diosgenin (GDN; Anatrace) was added to the cell lysate for solubilization at 4°C for 2 hours. After clarifying the insoluble materials by centrifugation at 8000g for 30 min, the supernatant was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 resin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 40 min by gentle agitation. The resin was packed into a gravity-flow column (Bio-Rad) and washed with 10 column volumes (CV) of buffer B [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% GDN, 5 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and 10 mM MgCl2] and 10 CV of buffer C [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.02% GDN). TRPM8MM was eluted by 5 CV of buffer C supplemented with FLAG peptide (0.128 mg mL−1). The eluent was concentrated and further purified on a Superose 6 Increase column (Cytiva Life Science) pre-equilibrated with buffer C.

TRPM8MM sample used for the inhibition part of the study was purified as follows. HEK293F cells were harvested, resuspended, and lysed in buffer A. 1% LMNG (Antrace) and 0.2% CHS (Anatrace) were added, and the cell lysate was solubilized by gentle agitation for 2 hours. Following centrifugation and anti-FLAG M2 resin binding, the resin was washed with 10 CV of buffer D [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 0.005% LMNG, 0.001% CHS, 5 mM ATP, and 10 mM MgCl2], 10 CV of buffer E [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 0.005% LMNG, and 0.001% CHS), and 10 CV of buffer F [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% LMNG, and 0.001% CHS]. TRPM8MM channels were eluted with 5 CV of buffer F supplemented with FLAG peptide. The eluent was concentrated and further purified on a Superose 6 Increase column pre-equilibrated with buffer F. EDTA (5 mM, pH 8) was added at all steps. To PEGylate the protein for grid preparation with AMTB (see details below), 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8) was replaced with 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 8) in the buffer used for anti-FLAG affinity column and size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

The full-length WT P. major TrpM8 (Trpm8PM) sequence (National Center for Biotechnology Information XP_015489531.1) was codon optimized and subcloned into a modified pEG BacMam vector (46) in frame with a C-terminal PreScission protease cleavage site followed by a FLAG tag and a 10x His tag. TRPM8PM channels were expressed by baculovirus-mediated transduction of HEK293S GnTi− (N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative) suspensions. The P2 BacMam virus was generated and used for infection for protein expression as previously described (8). Protein purification was carried out at 4°C. HEK293S GnTi− cells were resuspended in buffer A and lysed by a Dounce tissue grinder. 1% LMNG, 0.2% CHS, and 1 mM CaCl2 were added, and the cell lysate was solubilized by gentle agitation for 2 hours. Following centrifugation and anti-FLAG M2 resin binding, the resin was washed with 10 CV of buffer G [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% LMNG, 0.01% CHS, 5 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2], 10 CV of buffer H [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% LMNG, 0.01% CHS, and 1 mM CaCl2), and 10 CV of buffer I [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% LMNG, 0.01% CHS, and 1 mM CaCl2]. TRPM8PM channels were eluted with 5 CV of buffer I supplemented with FLAG peptide. The eluent was concentrated and further purified on a Superose 6 Increase column pre-equilibrated with buffer I.

Mutants used in the functional studies were generated by using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent), and sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing (Azenta Life Science).

Cryo-EM specimen preparation

Peak fractions eluted from SEC as described above were pooled and concentrated to ~0.5 to 0.8 mg mL−1 for grid preparation. Ligand incubation was carried at ambient temperature (20°C). For the TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+ sample, the protein was incubated with 1 mM diC8-PIP2 (Echelon Biosciences) and 1 mM CaCl2 for ~5 min. For the TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+ sample, the protein was incubated with 1 mM CaCl2 for ~30 min.

The ligand-free TRPM8MM sample was incubated at ambient temperature for 3 min and mixed with 100 μM fluorinated octyl maltoside (Anatrace) prior to grid freezing. For structures determined in the presence of antagonists, TRPM8MM protein was incubated with 400 μM AMG2850 (Alomone Labs) for ~5 min, 300 μM TC-I 2014 (Tocris Bioscience) for ~2 min, and 1 mM C3 and 300 μM TC-I 2014 for ~2 min, respectively. The concentrated TRPM8MM protein in HEPES-NaOH (pH 8) buffer was mixed with MS(PEG)12 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a molar ratio of 1:40 (TRPM8 monomer:reagent) and incubated on ice for 2 to 2.5 hours. AMTB (500 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated for ~2 min.

The concentrated TRPM8PM sample was incubated with 300 μM TC-I 2014 and an additional 1 mM CaCl2 for 1 hour at 4°C.

For each grid, 3 μL of the final sample was applied to freshly glow-discharged Quantifoil R 1.2/1.3 300-mesh Cu holey carbon grids with a 2-nm continuous carbon layer (Quantifoil). Grids were blotted for 1.5 to 5 s at blot force 0 using a Mark IV Vitrobot (FEI) at 20°C and 100% humidity followed by immediate plunge freezing in liquid ethane. The TRPM8PM_TC-I sample was preblotted for 3 s followed by 3.5-s blotting at force 0. Blotting time was optimized for image quality for data acquisition. Cryo-EM grids were stored in liquid nitrogen before screening and data collection.

Cryo-EM data acquisition

Grids were screened on a Talos Arctica transmission electron microscope (FEI) operated at 200 keV equipped with either a K2 or a K3 detector. All cryo-EM datasets were acquired on a Titan Krios transmission electron microscope at 300 keV (FEI) equipped with a K3 detector (Gatan) and a GIF BioQuantum energy filter (20-eV slit width; Gatan).

For the TRPM8MM_TC-I, TRPM8MM_AMTB, TRPM8MM_TC-I+C3, and TRPM8PM_TC-I structures, movies were acquired at a nominal magnification of 81,000× with a physical pixel size of 1.08 Å pixel−1 and a nominal defocus value from −0.7 to −2.2 μm. Each movie stack (40 frames) was acquired with an exposure time of 2.4 s, a dose rate of ~30 e− pixel−1 s−1, and a total cumulative dose of ~60 e− Å−2. Movies for the TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+ and TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+ structures were acquired in a similar manner, except each movie stack consisted of 60 frames and were acquired over 3.7-s exposure time with a dose rate of ~20 e− pixel−1 s−1.

Movies for the TRPM8MM_apo and TRPM8MM_AMG structures were acquired at a nominal magnification of 81,000× with a physical pixel size of 1.1 Å pixel−1 and a nominal defocus value from −0.7 to −2.5 μm. Each movie stack contained 53 frames and was acquired over an exposure time of 3.84 s with a dose rate of ~17 e− pixel−1 s−1, resulting in a total dose of ~53 e− Å−2.

Cryo-EM data processing

Data processing was carried out in RELION 4.0 (47, 48) and CryoSPARC v4 (49) following the previously published methods. In brief, beam-induced motion was corrected and movie frames were summed and dose-weighted using MotionCor2 (50) in RELION. The contrast transfer functions (CTFs) of non–dose-weighted summed images were estimated by Gctf (51). Micrographs were selected based on CTF parameters, including astigmatism, figure of merit, defocus values, and maximum resolution. Template-free Laplacian of Gaussian algorithm implemented in RELION was used for particle picking. Particles were extracted Fourier-binned 4×4 (64- or 80-pixel box size) and input to CryoSPARC for 2D classification. Contaminant classes and false picks were excluded, and the particles from the remaining classes were transferred to RELION and input to 3D autorefinement with C4 symmetry imposed without a mask. The published EM map of ligand-free collared flycatcher TRPM8 (EMD-7127) was rescaled and lowpass filtered to 30 Å as the initial 3D reference. The refined particles were recentered and re-extracted Fourier binned 2×2 (128- or 160-pixel box size) for 3D autorefinement with a soft mask. The subsequent 3D classification job without image alignment was carried out either with the full particles with a soft full mask or with subtracted particles using a mask covering the tetrameric MHR4-TMD-TRP domain (figs. S2 and S12). Particles from the class with the best resolved density for transmembrane helices or showing strong EM densities corresponding to ligands were selected and recentered and re-extracted without binning followed by 3D autorefinement with a soft full mask. After CTF refinement (52) and Bayesian polishing (53), the 3D reconstruction was input to CryoSPARC for nonuniform refinement (54). To improve the EM density quality at the TMD for the TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+ structure, we performed focused refinement after subtracting signals of the detergent belt and the cytoplasmic domain. The subtracted particles were refined using local refinement in CryoSPARC. For all the final 3D reconstructions, local resolution estimation and the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) validation were calculated using the gold-standard 0.143 FSC (55) in CryoSPARC.

Model building, refinement, and validation

Structure models were first manually built in Coot (56) using the published TRPM8MM PDB coordinates as the reference (see below). Secondary structural elements were rigid body fit into EM densities. Residue side chains were adjusted to the optimal rotamer conformations. Ideal geometry restraints were imposed as much as possible on secondary structures and side-chain rotamers during manual modeling in Coot. The published C1-state TRPM8MM_PIP2 structure (PDB 8E4N) was used as the reference to model TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+. The published O-state TRPM8MM structure (PDB 8E4L) was used as the reference to model TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+. The refined TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+ structure was subsequently used as the reference to model TRPM8MM_apo, TRPM8MM_TC-I, TRPM8MM_AMG, TRPM8MM_AMTB, and TRPM8MM_TC-I+C3 structures in the same manner. The pore loop, which was partially missing in the previous structures, was modeled in the six D-state TRPM8MM structures from the current study. TRPM8MM_TC-I from the current study and the published Ca2+-bound TRPM8PM structure (PDB 6O77) were used as the references to model TRPM8PM_TC-I in the current study.

The geometry restraints for PIP2, CHS, TC-I, AMG, AMTB, C3, and N-linked glycans were generated in the PHENIX eLBOW module (57) using isomeric or canonical SMILES strings and ideal bond lengths and angles.

Structure models built in Coot were input to real-space refinement in PHENIX against cryo-EM full maps along with ligand geometry restraints. Global minimization, rigid body refinement, and B-factor refinement with secondary structure restraints were enabled (58). The real-space refined models were examined for geometry outliers using the Molprobity server (http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/) (59), and errors were manually fixed in Coot. The FSCs of the structure model against the cryo-EM full map and against each half-map were calculated in PHENIX. The good agreement of the FSCs and the refinement statistics suggest that the structural models were not over-refined.

Coot, PyMOL (Schrödinger) (60), UCSF Chimera (61), and UCSF ChimeraX (62) were used for structural analysis and figure illustration. The Cα RMSD values were calculated in PyMOL using the “align” command and specifying structural alignment at Cα atoms only. The HOLE plots in Fig. 4 (B and C) and fig. S14B were generated in Coot, specifying Asp918 as the starting point and Gly984 as the ending point.

TEVC electrophysiology

The WT and mutant Trpm8MM genes were cloned into a pGEM-HE vector. The plasmid was linearized with XbaI restriction enzyme, and the complementary RNA (cRNA) was synthesized by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All defolliculated oocytes were ordered from Xenoocyte (Dexter, MI). cRNAs were injected into Xenopus laevis oocytes, which were then incubated at 17°C for 2 to 4 days in ND96 solution [96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) (with NaOH)] supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin (100 U mL−1; Gibco) and gentamicin (0.1 mg mL−1). Oocyte membrane voltage was controlled using an OC-725C oocyte clamp (Warner Instruments). Data were filtered at 1 to 3 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz using pClamp software (Molecular Devices) and a Digidata 1440A digitizer (Axon Instruments). Microelectrode resistances were 0.1 to 1 megaohms when filled with 3 M KCl.

All experiments were performed at room temperature (~20° to 22°C), except as indicated otherwise. For experiments in Figs. 1 (H and J) and 2A, the external recording buffer contained 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) (with KOH). C3 or menthol (Sigma-Aldrich) and TRPM8 antagonists TC-I 2014 (Tocris Bioscience), AMG2850 (Alomone Labs), AMTB hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich), and ruthenium red (RR; Sigma-Aldrich) were applied using a gravity-fed perfusion system for the corresponding measurements. For time course recording, the voltage was held at −60 mV then ramped to +60 mV for 300 ms every second. The percentage of current inhibition by antagonist X shown in Fig. 1 (H and J) was quantified using maximal current (Imax) induced by C3, antagonist X, and RR using Eq. 1

| (1) |

HEK293T cell transfection and whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology

HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco) and were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were seeded in six-well plates and were transiently transfected at ~50% confluency, with 1 μg of the WT and mutant Trpm8MM and Trpm8PM in pBacMam vector and 0.2 μg of enhanced green fluorescent protein using X-tremeGENE DNA transfection reagent (Roche). One to two days after the transfection, whole-cell patch clamp recordings were done at room temperature (~20° to 22°C) for menthol and C3 activation as described in the TEVC electrophysiology section. Cold stimuli were achieved by passing the external recording solution through glass capillary coils immersed in an ice-water bath maintained at about 0°C, and recordings were performed during constant perfusion with temperature measured using a thermistor (TA-29, Warner Instruments) located close to the cell. The thermistor was connected to the digitizer via a temperature controller (CL-100, Warner Instruments). Data were acquired with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices), and currents were lowpass filtered at 2 kHz (Axopatch 200B) and digitally sampled at 5 to 10 kHz (Digidata 1440 A). Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.5-mm outer diameter x 0.86-mm inner diameter x 75-mm length; Harvard Apparatus) using a Sutter P-1000 puller and heatpolished to final resistances between 2 and 4 megaohms. A series resistance compensation of 90% was used in all whole-cell recordings. Electrodes were filled with an intracellular solution containing 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES and adjusted to pH 7.4 (NaOH). For experiments in Fig. 6 (F to I), freshly prepared diC8-PI(4,5)P2 or diC8-PI(4)P (Echelon Biosciences) was added to the pipette solution to a final concentration of 200 μM. After breaking the cell membrane, cells were allowed to equilibrate with the pipette solution for 3 to 5 min before recording was carried out. All the electrophysiological data analyses were done using Igor Pro 6.2 (Wavemetrics).

MD simulations

Simulations were conducted in triplicate for (i) TRPM8MM_TC-I, (ii) TRPM8MM_AMG, (iii) TRPM8MM_AMTB from the current study, and (iv) TRPM8PM_TC-I (PDB 6O72) and (v) TRPM8PM_AMTB (PDB 6O6R) from the published study (18), where each structure was embedded in a mixed membrane of 2:1:1 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC):1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE):cholesterol. The simulations were performed using the CHARMM36m force field (lipid, protein, and nucleic acid) (63–66), transferable intermolecular potential 3-point (TIP3P) water model (67), and CGenFF (AMG, TC-I, and AMTB) (68). Each replica was simulated for 500 ns. The initial simulation systems were assembled in CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder (69–71) followed by the standard CHARMM-GUI six-step equilibration procedure. We performed additional equilibration of 50 ns, during which the protein backbone restraints were gradually loosened from 50 to 0 kJ mol−1 nm−2. Hydrogen mass repartition was applied to the simulation systems (72), and a 2-fs time step was used for equilibration and production in OpenMM (73). The van der Waals interactions were truncated at 12 Å with a force-switching function applied between 10 to 12 Å. Each system was maintained at a constant particle number, 1-bar pressure, and 300.15 K temperature under NPT conditions.

For ligand RMSD analysis of TC-I and AMG, each interfacial binding site was aligned based on the TRPM8MM helical residues (S3: 796 to 718, S4 and S5: 830 to 880, S6: 967 to 984, neighboring S5: 863 to 890, and neighboring S6: 952 to 983) and then ligand RMSD was calculated based on the heavy atoms of the ligands. For ligand RMSD analysis of AMTB, each VSLD binding site was aligned based on the TRPM8MM binding site residues (S1 to S4: 734 to 850 and TRP: 994 to 1017) and the ligand RMSD of AMTB was also based on the nonhydrogen atoms.

Thermodynamic modeling

The steady-state open probabilities (PO) for the inhibitor titrations were calculated with Eq. 2 based on the raw electrophysiology data shown in fig. S6 (E and F), where Ix is the steady-state current at a given concentration of inhibitor, Imax is the maximal current reached, and Imin is the minimum current at the highest concentration of inhibitor. Ix takes into account the initial desensitization, most apparent at high concentrations of calcium

| (2) |

The data were fit using the thermodynamic scheme of the model depicted in Fig. 2B, where the fit PO is given by Eq. 3. This assumes that all of the channels open or desensitize prior to the start of the inhibitor titration; therefore, no C-state channel should exist within the resolution of measurement.

| (3) |

The states are calculated with O being the reference state (O = 1) and the other states given as D (D = K2), OI (OI = [I]K3), and DI (DI = cK2K3). K2 and K3 are the forward equilibrium constants for inhibitor binding and desensitization, respectively. c is a thermodynamic coupling term, where c > 1 indicates positive coupling between channel desensitization and inhibitor binding and c ≤ 1 indicates no or anticooperative coupling. The data were fitted using custom MatLab scripts (Mathworks, R2023a) where c, K2, and K3 values were allowed to vary. However, because large fitting errors resulted when c, K2, and K3 were all allowed to float, c was held constant while K2 and K3 were varied. On the basis of the fit quality, as quantified by the sum of squared residuals (SSQ or resnorm), values of c ≥ 104 resulted in good quality fits (Fig. 2D and fig. S8C) with improved fitting parameter errors, given as 95% confidence intervals. Fit values in fig. S8D were therefore determined with c fixed at 104. The concentration of calcium is implicitly accounted for by fitting K3 for each concentration of calcium, where increasing calcium concentrations result in predictably larger values of K3 (Fig. 2E). For the plots of state populations (fig. S8, E and F), the probability (PX) of a given state (X) is given by Eq. 4

| (4) |

The determined fit values of c, K2, and K3 were used in addition to a fixed value for K1 of 103, which was the lowest value that does not affect the fit quality. For this expanded model, C is therefore set as the reference state where O = K1, D = K1K3, OI = [I]K1K2, and DI = cK1K2K3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Igor Pro 6.2, Excel Office 365, and GraphPad Prism 7.0. All quantitative data are represented as means ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed by Student’s two-tailed unpaired t test. Comparisons among more than two groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Comparisons among more than two groups with two independent variables were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post hoc test. Differences were considered significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, as appropriate.

Acknowledgments

Cryo-EM data were screened and collected at the Duke University Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (SMIF) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). We thank N. Bhattacharya at the SMIF and E. Viverette and M. Borgnia at the NIEHS for assistance with the microscope operation and support for the project.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R35NS097241 (S.-Y.L.), National Institutes of Health grant R01EY031698 (S.-Y.L.), and National Institutes of Health grant R01GM138472 (W.I.).

Author contributions: Y.Y. conducted all biochemical preparation, cryo-EM experiments, model building, and single-particle 3D reconstruction under the guidance of S.-Y.L. C.-G.P., F.Z., and Y.Y. carried out electrophysiological recordings under the guidance of S.-Y.L. J.G.F. performed thermodynamic modeling. S.F. performed all MD simulations under the guidance of W.I. Y.S. helped part of biochemical preparation and cryo-EM experiments. Y.Y., S.-Y.L., and J.G.F. wrote the paper.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. For the D-state TRPM8MM_apo, TRPM8MM_TC-I, TRPM8MM_AMG, TRPM8MM_AMTB, TRPM8MM_TC-I+C3, TRPM8PM_TC-I, TRPM8MM_PIP2+Ca2+, and TRPM8MM_ΔPIP2+Ca2+ structures, the coordinates are deposited in the PDB with the PDB IDs 9B6D, 9B6E, 9B6F, 9B6G, 9B6H, 9B6I, 9B6J, and 9B6K, respectively; the cryo-EM density maps are deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with the IDs EMD-44255, EMD-44256, EMD-44257, EMD-44258, EMD-44259, EMD-44260, EMD-44261, and EMD-44262, respectively.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S17

Table S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Benda J., Neural adaptation. Curr. Biol. 31, R110–R116 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wark B., Lundstrom B. N., Fairhall A., Sensory adaptation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 423–429 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D. D. McKemy, “TRPM8: The cold and menthol receptor” in TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades, W. B. Liedtke, S. Heller, Eds. (CRC Press, 2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bautista D. M., Siemens J., Glazer J. M., Tsuruda P. R., Basbaum A. I., Stucky C. L., Jordt S. E., Julius D., The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature 448, 204–208 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colburn R. W., Lubin M. L., Stone D. J. Jr., Wang Y., Lawrence D., D'Andrea M. R., Brandt M. R., Liu Y., Flores C. M., Qin N., Attenuated cold sensitivity in TRPM8 null mice. Neuron 54, 379–386 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu B., Qin F., Functional control of cold- and menthol-sensitive TRPM8 ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Neurosci. 25, 1674–1681 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohacs T., Lopes C. M., Michailidis I., Logothetis D. E., PI(4,5)P2 regulates the activation and desensitization of TRPM8 channels through the TRP domain. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 626–634 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin Y., Le S. C., Hsu A. L., Borgnia M. J., Yang H., Lee S. Y., Structural basis of cooling agent and lipid sensing by the cold-activated TRPM8 channel. Science 363, eaav9334 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssens A., Gees M., Toth B. I., Ghosh D., Mulier M., Vennekens R., Vriens J., Talavera K., Voets T., Definition of two agonist types at the mammalian cold-activated channel TRPM8. eLife 5, e17240 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin Y., Zhang F., Feng S., Butay K. J., Borgnia M. J., Im W., Lee S. Y., Activation mechanism of the mouse cold-sensing TRPM8 channel by cooling agonist and PIP(2). Science 378, eadd1268 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin Y., Wu M., Zubcevic L., Borschel W. F., Lander G. C., Lee S. Y., Structure of the cold- and menthol-sensing ion channel TRPM8. Science 359, 237–241 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenshalo D. R., Scott H. A. Jr., Temporal course of thermal adaptation. Science 151, 1095–1096 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid G., ThermoTRP channels and cold sensing: What are they really up to? Pflugers Arch. 451, 250–263 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid G., Flonta M. L., Physiology. Cold current in thermoreceptive neurons. Nature 413, 480 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenshalo D. R., Duclaux R., Response characteristics of cutaneous cold receptors in the monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 40, 319–332 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okazawa M., Terauchi T., Shiraki T., Matsumura K., Kobayashi S., l-Menthol-induced [Ca2+]i increase and impulses in cultured sensory neurons. Neuroreport 11, 2151–2155 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid G., Babes A., Pluteanu F., A cold- and menthol-activated current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones: Properties and role in cold transduction. J. Physiol. 545, 595–614 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diver M. M., Cheng Y., Julius D., Structural insights into TRPM8 inhibition and desensitization. Science 365, 1434–1440 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao C., Xie Y., Xu L., Ye F., Xu X., Yang W., Yang F., Guo J., Structures of a mammalian TRPM8 in closed state. Nat. Commun. 13, 3113 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yudin Y., Rohacs T., Regulation of TRPM8 channel activity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 353, 68–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels R. L., Takashima Y., McKemy D. D., Activity of the neuronal cold sensor TRPM8 is regulated by phospholipase C via the phospholipid phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1570–1582 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chasman D. I., Schurks M., Anttila V., de Vries B., Schminke U., Launer L. J., Terwindt G. M., van den Maagdenberg A. M., Fendrich K., Volzke H., Ernst F., Griffiths L. R., Buring J. E., Kallela M., Freilinger T., Kubisch C., Ridker P. M., Palotie A., Ferrari M. D., Hoffmann W., Zee R. Y., Kurth T., Genome-wide association study reveals three susceptibility loci for common migraine in the general population. Nat. Genet. 43, 695–698 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horne D. B., Biswas K., Brown J., Bartberger M. D., Clarine J., Davis C. D., Gore V. K., Harried S., Horner M., Kaller M. R., Lehto S. G., Liu Q., Ma V. V., Monenschein H., Nguyen T. T., Yuan C. C., Youngblood B. D., Zhang M., Zhong W., Allen J. R., Chen J. J., Gavva N. R., Discovery of TRPM8 antagonist (S)-6-(((3-fluoro-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)(3-fluoropyridin-2-yl)methyl)carbamoyl)nicotinic acid (AMG 333), a clinical candidate for the treatment of migraine. J. Med. Chem. 61, 8186–8201 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez-Muniz R., Bonache M. A., Martin-Escura C., Gomez-Monterrey I., Recent progress in TRPM8 modulation: An update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2618 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weyer A. D., Lehto S. G., Development of TRPM8 antagonists to treat chronic pain and migraine. Pharmaceuticals 10, 37 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrews M. D., Af Forselles K., Beaumont K., Galan S. R., Glossop P. A., Grenie M., Jessiman A., Kenyon A. S., Lunn G., Maw G., Owen R. M., Pryde D. C., Roberts D., Tran T. D., Discovery of a selective TRPM8 antagonist with clinical efficacy in cold-related pain. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 6, 419–424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winchester W. J., Gore K., Glatt S., Petit W., Gardiner J. C., Conlon K., Postlethwaite M., Saintot P. P., Roberts S., Gosset J. R., Matsuura T., Andrews M. D., Glossop P. A., Palmer M. J., Clear N., Collins S., Beaumont K., Reynolds D. S., Inhibition of TRPM8 channels reduces pain in the cold pressor test in humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 351, 259–269 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvo R. R., Meegalla S. K., Parks D. J., Parsons W. H., Ballentine S. K., Lubin M. L., Schneider C., Colburn R. W., Flores C. M., Player M. R., Discovery of vinylcycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazole TRPM8 antagonists effective in the treatment of cold allodynia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 1903–1907 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertamino A., Iraci N., Ostacolo C., Ambrosino P., Musella S., Di Sarno V., Ciaglia T., Pepe G., Sala M., Soldovieri M. V., Mosca I., Gonzalez-Rodriguez S., Fernandez-Carvajal A., Ferrer-Montiel A., Novellino E., Taglialatela M., Campiglia P., Gomez-Monterrey I., Identification of a potent tryptophan-based TRPM8 antagonist with in vivo analgesic activity. J. Med. Chem. 61, 6140–6152 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Caro C., Russo R., Avagliano C., Cristiano C., Calignano A., Aramini A., Bianchini G., Allegretti M., Brandolini L., Antinociceptive effect of two novel transient receptor potential melastatin 8 antagonists in acute and chronic pain models in rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 1691–1706 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin-Escura C., Medina-Peris A., Spear L. A., de la Torre Martinez R., Olivos-Ore L. A., Barahona M. V., Gonzalez-Rodriguez S., Fernandez-Ballester G., Fernandez-Carvajal A., Artalejo A. R., Ferrer-Montiel A., Gonzalez-Muniz R., β-Lactam TRPM8 antagonist RGM8-51 displays antinociceptive activity in different animal models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2692 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parks D. J., Parsons W. H., Colburn R. W., Meegalla S. K., Ballentine S. K., Illig C. R., Qin N., Liu Y., Hutchinson T. L., Lubin M. L., Stone D. J. Jr., Baker J. F., Schneider C. R., Ma J., Damiano B. P., Flores C. M., Player M. R., Design and optimization of benzimidazole-containing transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 54, 233–247 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lashinger E. S., Steiginga M. S., Hieble J. P., Leon L. A., Gardner S. D., Nagilla R., Davenport E. A., Hoffman B. E., Laping N. J., Su X., AMTB, a TRPM8 channel blocker: Evidence in rats for activity in overactive bladder and painful bladder syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295, F803–F810 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aizawa N., Fujimori Y., Kobayashi J. I., Nakanishi O., Hirasawa H., Kume H., Homma Y., Igawa Y., KPR-2579, a novel TRPM8 antagonist, inhibits acetic acid-induced bladder afferent hyperactivity in rats. Neurourol. Urodyn. 37, 1633–1640 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y., Leng A., Li L., Yang B., Shen S., Chen H., Zhu E., Xu Q., Ma X., Shi P., Liu Y., Liu T., Li L., Li K., Zhang D., Xiao J., AMTB, a TRPM8 antagonist, suppresses growth and metastasis of osteosarcoma through repressing the TGFβ signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 13, 288 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehto S. G., Weyer A. D., Zhang M., Youngblood B. D., Wang J., Wang W., Kerstein P. C., Davis C., Wild K. D., Stucky C. L., Gavva N. R., AMG2850, a potent and selective TRPM8 antagonist, is not effective in rat models of inflammatory mechanical hypersensitivity and neuropathic tactile allodynia. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 388, 465–476 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guterres H., Park S.-J., Zhang H., Perone T., Kim J., Im W., CHARMM-GUI high-throughput simulator for efficient evaluation of protein–ligand interactions with different force fields. Protein Sci. 31, e4413 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jara-Oseguera A., Bae C., Swartz K. J., An external sodium ion binding site controls allosteric gating in TRPV1 channels. eLife 5, e13356 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geron M., Kumar R., Zhou W., Faraldo-Gomez J. D., Vasquez V., Priel A., TRPV1 pore turret dictates distinct DkTx and capsaicin gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E11837–E11846 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon D. H., Zhang F., Fedor J. G., Suo Y., Lee S. Y., Vanilloid-dependent TRPV1 opening trajectory from cryoEM ensemble analysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 2874 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zubcevic L., Lee S. Y., The role of π-helices in TRP channel gating. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 58, 314–323 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin Y., Lee S. Y., Current view of ligand and lipid recognition by the menthol receptor TRPM8. Trends Biochem. Sci. 45, 806–819 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yudin Y., Lukacs V., Cao C., Rohacs T., Decrease in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels mediates desensitization of the cold sensor TRPM8 channels. J. Physiol. 589, 6007–6027 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y., Cao E., Julius D., Cheng Y., TRPV1 structures in nanodiscs reveal mechanisms of ligand and lipid action. Nature 534, 347–351 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwon D. H., Zhang F., Suo Y., Bouvette J., Borgnia M. J., Lee S. Y., Heat-dependent opening of TRPV1 in the presence of capsaicin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28, 554–563 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goehring A., Lee C. H., Wang K. H., Michel J. C., Claxton D. P., Baconguis I., Althoff T., Fischer S., Garcia K. C., Gouaux E., Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2574–2585 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zivanov J., Nakane T., Forsberg B. O., Kimanius D., Hagen W. J., Lindahl E., Scheres S. H., New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimanius D., Dong L., Sharov G., Nakane T., Scheres S. H. W., New tools for automated cryo-EM single-particle analysis in RELION-4.0. Biochem. J. 478, 4169–4185 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J., Brubaker M. A., cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]