Abstract

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) facilitates the formation of membraneless organelles within cells, with implications in various biological processes and disease states. AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) is a chromatin remodeling factor frequently associated with cancer mutations, yet its functional mechanism remains largely unknown. Here, we find that ARID1A harbors a prion-like domain (PrLD), which facilitates the formation of liquid condensates through PrLD-mediated LLPS. The nuclear condensates formed by ARID1A LLPS are significantly elevated in Ewing’s sarcoma patient specimen. Disruption of ARID1A LLPS results in diminished proliferative and invasive abilities in Ewing’s sarcoma cells. Through genome-wide chromatin structure and transcription profiling, we identify that the ARID1A condensate localizes to EWS/FLI1 target enhancers and induces long-range chromatin architectural changes by forming functional chromatin remodeling hubs at oncogenic target genes. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that ARID1A promotes oncogenic potential through PrLD-mediated LLPS, offering a potential therapeutic approach for treating Ewing’s sarcoma.

Subject terms: Chromatin remodelling, Cell biology, Epigenomics

ARID1A is a chromatin remodeling protein frequently mutated in cancer. Here the authors report that ARID1A plays a role in forming membraneless organelles through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). ARID1A condensates were elevated in Ewing’s sarcoma patients.

Introduction

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) facilitates essential cellular processes including transcription. Molecules that undergo LLPS typically display condensates and form distinct droplets inside the cell. In general, intrinsically disordered regions (IDR) drive LLPS through multivalent interactions between multiple amino acid residues1. Prion-like domains (PrLDs) also display intrinsic disorder and exhibit LLPS behavior2. Recent studies revealed that PrLDs lack stable molecular structure, and aromatic residues within these domains function as “stickers” to mediate direct molecular interaction, whereas polar residues localized in between each aromatic residue function as “spacers” to distribute stickers evenly throughout the PrLD and modulate LLPS2,3. The PrLD is important for driving diverse biological functions. For example, early flowering 3 (ELF3) acts as a thermosensor through PrLD-mediated LLPS in the thermal induction of flowering in Arabidopsis4. The PrLD of early B-cell factor 1 (EBF1) is indispensable for B-cell lineage commitment5.

Aberrant forms of LLPS are associated with various diseases including cancer6,7. The eleven-nineteen-leukemia (ENL) protein possesses the Yaf9, ENL, AF9, Taf14, Sas5 (YEATS) domain that is a reader module recognizing histone lysine acylation selectively8. A recurrent mutation in the YEATS domain of the ENL protein identified in Wilms’ tumor resulted in a greater degree of ENL self-association and the formation of distinct nuclear puncta9. In addition, self-association upon mutation, including in-frame insertion or deletion within the YEATS domain, led to increased ENL occupancy at target genomic loci along with the recruitment of elongation factors, resulting in abnormal target gene expression and consequent developmental defects9. In another study, disease-associated SHP2 mutants (D61G, E76A, E76K, Y279C, and R498L), found in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemias and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines, were prone to LLPS through multivalent electrostatic interactions, whereas its wild type (WT) form remains diffusive10,11. The mutant SHP2 acts as a scaffold protein that forms condensates to recruit and activate WT SHP2, promoting mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) hyperactivation and the pathogenesis of SHP2-associated human diseases11.

The nucleus houses condensates created by LLPS that both control gene transcription by creating active transcription hubs12 and compartmentalize transcriptional components, including transcription factor, cofactor, and RNA polymerase, to enhance gene expression12. In addition, these transcription condensates promote a three-dimensional morphological alteration in the chromatin architecture, generating transcriptional hot spots13,14. The fusion protein NUP98/HOXA9 in human hematological cancers has been shown to create transcriptional condensates that prompt the origination of chromatin loops and activate gene transcription13. Moreover, the fusion protein YAP is known to form a nuclear condensate that modifies chromatin loop architecture to upregulate an oncogenic transcriptional program in human ependymoma14.

ARID1A is a chromatin remodeling factor which is known to be a component of Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1)/Brahma homolog (BRM) associated factor (BAF) complex. Accumulating evidence supports that ARID1A functions as a transcriptional activator by opening target gene loci occupied by various transcription factors. In colorectal cancer, ARID1A has been shown to act at the activation protein 1 (AP1)-occupied enhancer and upregulates associated genes involved in MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) signaling pathway15. Further, ARID1A has been found to occupy luminal transcription factor loci bound by estrogen receptor α (ERα) and Forkhead Box A1 (FOXA1) in breast cancer16. Loss of ARID1A results in luminal to basal transition and resistance to endocrine therapy. ARID1A has been shown to be frequently mutated in cancers, and recurrent mutations in ARID1A have been identified in a wide variety of cancers, including ovarian, breast, and pancreatic cancers17–19. In the case of hepatocellular carcinoma, high expression of ARID1A promotes oncogenic potential by increasing cytochrome P450-mediated oxidative stress20. These studies suggest the possibility that ARID1A plays a critical role in regulating oncogenesis.

In this study, we found that PrLDs embedded within the IDR of ARID1A drive LLPS through multivalent interactions between aromatic residues. Ewing’s sarcoma patient samples exhibit a stronger tendency of ARID1A condensation compared to normal counterpart. Based on genome-wide analysis, we identified that ARID1A upregulates the expression of EWS/FLI1 target genes by active chromatin reconfiguration, and the subsequent inhibition of LLPS attenuates downstream target gene expression. These findings reveal previously unidentified molecular mechanism through which LLPS of ARID1A fuels the cancerous activity of Ewing’s sarcoma, highlighting it as a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma.

Results

Prion-like domain drives liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) of ARID1A in the nucleus

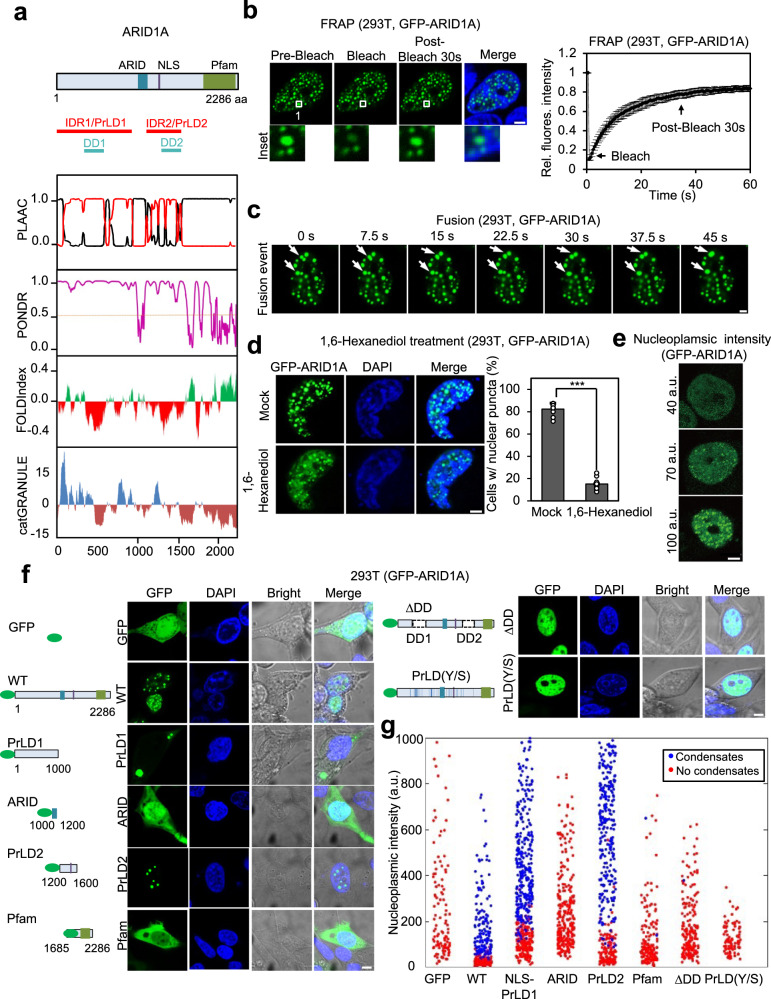

ARID1A contains a few annotated domains, including the ARID DNA-binding domain, a nuclear localization signal (NLS), and a Pfam homology domain21. Using PONDR and PLAAC, bioinformatic algorithms that are used to identify IDRs and PrLD, respectively, we found that ARID1A is primarily composed of PrLD (Fig. 1a). ARID1A possesses two PrLDs separated by the ARID domain (hereafter referred to as PrLD1 and PrLD2). Moreover, FOLDIndex, a program that scores protein unfolding, indicated that both PrLD1 and PrLD2 contain smaller regions that are markedly unfolded and disordered compared to surrounding regions (annotated as disordered domain (DD) 1 and 2) (Fig. 1a)22. Lastly, catGRANULE analysis revealed that the phase separation propensity is high for both PrLD1 and PrLD2 (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. ARID1A undergoes liquid–liquid phase separation through PrLDs.

a Domain structure and intrinsic disorder tendency of ARID1A. The top panel shows the domains of ARID1A, along with PLAAC analysis, PONDR analysis, FOLD analysis, and catGRANULE analysis. b Representative images of the FRAP experiment conducted in GFP-ARID1A transfected 293T cells. The white box highlights the organelle subjected to targeted bleaching. The bottom presents the quantification of FRAP data for GFP-ARID1A puncta. Bleaching occurred at t = 0 s. Initial fluorescence was used as the reference value to calculate relative fluorescence intensity. Data are presented as the means ± SEMs (n = 9), n = individual ARID1A nuclear condensate. Scale bar: 5 μm. c Live-cell imaging of 293T cells expressing GFP-ARID1A. The arrows indicate representative ARID1A puncta that fused over time. Scale bar: 2 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcome. d GFP-ARID1A formed nuclear puncta in 293T cells. Cells transfected with GFP-ARID1A were treated with or without 6% Hex for 5 min and imaged using confocal microscopy. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The quantification on the right shows the percentage of cells with nuclear puncta. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001. Statistics by two-tailed t-test. Twelve transfected cells from each group (mock and hexanediol treatment) were analyzed; n = 12 biologically independent samples. Scale bar: 5 μm. e Representative confocal images of 293T cells expressing GFP-ARID1A at different fluorescence intensities. Scale bar: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcome. f Representative confocal images of 293T cells transfected with different forms of recombinant GFP-ARID1A constructs, including GFP, GFP-ARID1A, GFP-PrLD1, GFP-ARID, GFP-PrLD2, GFP-Pfam, GFP-ARID1A PrLD(Y/S), and GFP-ΔDD mutant. Scale bar: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. g Quantitative phase diagram depicting the intra-nuclear concentration of ARID1A domains and mutants observed. Each dot represents the ARID1A concentration from a unique cell. Red indicates positive phase separation, while blue indicates negative phase separation. (a.u. = arbitrary unit). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To examine whether ARID1A exhibits phase separation in cells, we expressed GFP-ARID1A into 293T cells and monitored its subcellular distribution. GFP-ARID1A exhibited distinct nuclear condensates (Fig. 1b). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments on the nuclear ARID1A condensates showed rapid molecular rearrangements, confirming that ARID1A condensates are indeed liquid-like (Fig. 1b). The ARID1A foci often grew in size through frequent fusion events and exhibited highly spherical morphology, suggesting that they have liquid-like physical properties (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, intracellular ARID1A condensates were dissolved significantly upon the treatment of 1,6-hexanediol—compound that disrupts weak hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 1d). GFP-ARID1A generated discrete nuclear foci in a manner dependent on its concentration (Fig. 1e).

To evaluate the LLPS ability of ARID1A in vitro, we purified GFP-labeled ARID1A protein and performed in vitro droplet assay. When examined with fluorescence microscopy, we found that GFP-ARID1A indeed formed highly spherical droplet-like assemblies (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Consistent with the liquid state, ARID1A assemblies exhibited rapid shape relaxation after fusing with one another (Supplementary Fig. 1a). To further probe protein dynamics within ARID1A assemblies, we performed FRAP experiments23. Bleached regions showed a near-complete fluorescence recovery (Supplementary Fig. 1b), confirming that GFP-ARID1A formed dense liquid droplets with high molecular mobility. As expected for LLPS, we found that ARID1A droplets were microscopically observable only above a threshold concentration of 1–1.25 μM and bigger droplets were observed at higher protein concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The assembled droplets were highly susceptible to 1,6-hexanediol treatment, indicating that hydrophobic interactions play important roles in driving ARID1A phase separation (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Taken together, our results indicate that ARID1A undergoes LLPS both in vitro and in cells.

We then sought to comprehensively identify the regions of ARID1A that are responsible for driving LLPS. By employing PONDR and PLAAC amino acid sequence-based analysis, we observed that ARID1A possesses two ordered domains including the ARID domain and the Pfam homology domain and two DDs including PrLD1, and PrLD2. Proteins that segregate through the phase separation process generally have specific domains required for driving condensation24,25. To dissect the parts of ARID1A which play a key role in inducing LLPS, we generated several truncation variants which included different regions of ARID1A, and observed their cellular localization (Fig. 1f). GFP-fused full-length ARID1A formed distinct nuclear condensates, whereas control GFP expression showed a widely spread staining pattern throughout the entire cell. Since PrLD1 does not have an NLS, it remained in the cytoplasm, forming a big, clearly visible segment in the bright field. Conversely, the NLS-possessing PrLD2 took the form of a distinct condensate within the nucleus. ARID DNA-binding domain and Pfam homology domain, which lack PrLD, failed to undergo LLPS (Fig. 1f). To confirm that PrLD1 and PrLD2 are the key regions that induce ARID1A LLPS, we generated an ARID1A deletion mutant lacking DDs of ARID1A (ΔDD). This ΔDD mutant failed to undergo LLPS (Fig. 1f), proving the indispensable roles of DDs of PrLD1 and PrLD2 in ARID1A condensation.

Intermolecular interactions driving phase separation of associative polymers have been described using a stickers-and-spacers framework3. Stickers exhibit associative interactions with one another to drive phase separation. For PrLDs, aromatic residues such as tyrosine are shown to act as stickers3. On the other hand, spacers are linkers that connect stickers, and play modulatory roles in phase separation. To probe whether tyrosine residues are important for the phase separation of ARID1A, we generated an ARID1A variant of which its 52 tyrosine residues in the PrLDs were replaced with serine. Live-cell imaging using the ARID1A PrLD(Y/S) mutant revealed that the disruption of tyrosine interactions completely abolished the PrLD-mediated LLPS of ARID1A (Fig. 1f), confirming that aromatic residues within the PrLD are key drivers of LLPS.

To corroborate our findings, in vitro droplet assay using purified recombinant proteins was performed (Supplementary Fig. 1e). PrLD1 and PrLD2 regions exhibited strong concentration-dependent phase separation behaviors, similar to the full-length ARID1A. In contrast, neither ARID domain nor Pfam homology domain showed phase separation up to 10 μM. In agreement with results from in cellulo experiments, ΔDD and PrLD(Y/S) mutant failed to undergo LLPS (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Lastly, we studied the concentration-related formation of nuclear ARID1A condensates by tracking the nucleoplasmic concentrations at which ARID1A proteins started to form condensate. As a result, we discovered a discernible threshold at which ARID1A initiates the formation of condensates. Condensate-forming proteins, including ARID1A WT, NLS-PrLD1, and PrLD2, exhibited a gradual increase in the size and number of nuclear condensates as their molecular concentrations surpassed the threshold. (Fig. 1g). Nevertheless, ARID domain, Pfam homology domain, and LLPS deficient mutants were incapable of forming nuclear condensate, proving the critical role of PrLDs of ARID1A in condensate formation (Fig. 1g).

Given that ARID1A is frequently mutated and recognized as a potential tumor suppressor, we examined point mutations that accumulate in the PrLDs of ARID1A17–19. Among these, we identified two frequently mutated cancer missense mutations, R774C and R1223C, and analyzed their nuclear localization patterns (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Subsequently, we observed that these mutants formed nuclear condensates morphologically comparable to those formed by the WT protein (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Furthermore, our analysis revealed that the condensates formed by these mutants exhibited liquid-like properties (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e).

ARID1A requires both PrLD and Pfam homology domain to incorporate BAF subunits into condensate

ARID1A serves as a structural core and scaffold in the structural organization of the BAF complex, and C-terminal Pfam homology domain of ARID1A mediates direct molecular contact with other BAF subunits to maintain a stable base module of BAF complexes26. Therefore, we next examined whether the ARID1A condensate possesses the ability to compartmentalize its chromatin remodeler cofactors via phase separation. First, we checked whether the loss of ARID1A LLPS can affect its interaction with BAF subunits. We performed a co-immunoprecipitation assay and found that both WT and ΔDD mutant maintain its interaction with BAF complex subunits including SMARCA2, SMARCB, SMARCD, SMARCC1, and SMARCE, whereas ΔPfam mutant failed to interact with BAF complex subunits (Fig. 2a). These data indicate that phase separation ability of ARID1A does not affect its interaction with BAF complex.

Fig. 2. ARID1A requires both PrLDs and Pfam homology domain to incorporate BAF subunits into condensates.

a Co-immunoprecipitation assay performed to detect the interaction between endogenous BAF complex subunit and ARID1A wild type (WT), ΔDD, or ΔPfam mutant expressed in 293T cells. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. b Representative confocal images showing the cellular localization of different GFP-BAF complex subunits. Scale bar: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. c Representative confocal images demonstrating the colocalization pattern of recombinant ARID1A proteins (green) and SMARCB1 (red). Scale bar: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. d Representative confocal images illustrating the colocalization pattern of recombinant ARID1A proteins (green) and SMARCD1 (red). Scale bar: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. e Schematics of ARID1A Corelet system. f Representative confocal images of the Corelet system using PrLD1-mch-SspB or PrLD1-Pfam-mch-SspB to observe recruitment of BAF complex subunit upon blue light stimulation. Scale bars: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. g Representative confocal images of 293T cells transfected with recombinant ARID1A and immunostained with anti-SMARCD and anti-SMARCC1 antibodies. Scale bars: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

When overexpressed in 293T cells, unlike ARID1A, other BAF subunits were diffusively distributed (Fig. 2b). To investigate the capacity of ARID1A to compartmentalize the BAF subunits, we co-expressed various ARID1A truncation constructs with either SMARCB1 (Fig. 2c) or SMARCD1 (Fig. 2d). Due to lack of NLS in PrLD1, NLS was artificially added to acquire nuclear condensate of PrLD1. Though NLS-PrLD1 formed a nuclear condensate, SMARCB1 and SMARCD1 remained diffuse, thus the lack of partitioning was revealed. Successful incorporation BAF subunits by ARID1A WT condensate was contrasted by the Y/S mutants of PrLD and ΔDD, as the two could not form a nuclear droplet, and SMARCB1 and SMARCD1 were not segregated appropriately. Lastly, analogous to NLS-PrLD1, ΔPfam formed distinct condensates in the nucleus yet failed to compartmentalize SMARCB1 and SMARCD1 (Fig. 2c, d). Together, these data indicate that Pfam domain of ARID1A is essential not only for its interaction with BAF complex subunits but also for partitioning of BAF complex subunits into ARID1A condensate.

Our results suggest the modular domain organization of ARID1A for phase separation: PrLDs drive the formation of condensates while the Pfam domain tunes their compositions. To further test this idea, we took a synthetic approach to build up condensates using the previously developed light-inducible Corelet system (Fig. 2e). The Corelet components include a 24-mer ferritin core appended with improved light induced dimer (iLID) and IDRs fused with stringent starvation protein B (sspB). Blue light activation leads to dimerization between iLID and sspB, giving rise to IDR oligomers, which can ultimately trigger phase separation (Fig. 2e). When PrLD1 of ARID1A was used as an IDR fusion to sspB, we observed a strong blue light dependent formation of nuclear condensates. However, PrLD1 Corelet condensates failed to recruit SMARCB1 and SMARCD1. In a sharp contrast, appending Pfam domain to PrLD1 (PrLD1-Pfam-sspB) altered the composition of Corelet condensates with clear partitioning of these BAF complex subunits (Fig. 2f).

To validate that ARID1A condensates hold endogenous BAF subunits, we conducted immunocytochemistry using anti-SMARCD1 and anti-SMARCC1 antibodies. Co-immunostaining of GFP-ARID1A condensate and endogenous BAF showed a notable concentration of BAF subunits (Fig. 2g). The molecules were diffusive when a phase separation defective mutant of ARID1A was expressed. In addition, the condensate formed by ARID1A without the Pfam domain was unable to attract BAF components and they stayed diffusive in the nucleus (Fig. 2g). Thus, our data indicate that ARID1A builds nuclear condensates via PrLD-induced phase separation and recruits BAF subunits with the aid of Pfam homology domain.

Loss of ARID1A LLPS significantly reduces proliferative and invasive property of Ewing’s sarcoma

Next, we examined the biological context in which endogenous ARID1A LLPS is observed. Quantitative proteomics to analyze 375 cancer cell lines have generated a cancer cell line encyclopedia27. Taking advantage of this resource, we explored the protein levels of ARID1A across multiple types of cancer, and found that ARID1A protein level was significantly high in Ewing’s sarcoma compared to many other cancer types (Fig. 3a). This unusual high expression of ARID1A in Ewing’s sarcoma was validated by immunoblot analysis in multiple cancer cell lines including Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines (A673 and SK-N-MC) (Fig. 3b). Since BAF complex subunits are enriched inside the ARID1A condensate, we further analyzed protein expression of BAF subunits using CCLE data (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). As in case of ARID1A, BAF subunits also showed increased protein level specifically in Ewing’s sarcoma (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Moreover, protein levels of ARID1A and each BAF subunit were positively correlated across various cancer types (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Loss of ARID1A LLPS significantly reduces proliferative and invasive property of Ewing’s sarcoma.

a Expression levels of ARID1A protein in different types of cancer obtained from the cancer cell line encyclopedia. b Representative immunoblot image measuring ARID1A protein levels in various cancer cell lines. The quantification represents ARID1A/β-actin protein density ratio. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. c Immunohistochemistry results showing ARID1A staining in normal bone tissue and two Ewing’s sarcoma patient tissues. Scale bars: 10 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. d Immnuocytochemistry image illustrating endogenous ARID1A localization in WT, ARID1A−/−, ARID1A−/− + WT and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD cells. Scale bars: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. e Left: wound healing assay conducted on WT, ARID1A−/−, ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines. Right: quantification of the wound healing assay. Bars represent the SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS non-significant. n = 10 technical replicate of wound closures. Statistical analysis performed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test on 48 h samples of ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines. Scale bar: 500 μm. f Left: spheroid formation assay performed for four cell lines over 4 days. Right: quantification of the spheroid formation assay. Bars represents the mean ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS non-significant. n = 10 technical replicates of spheroids. Statistical analysis performed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test on day 4 samples of ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines. Scale bar: 500 μm. g Left: spheroid invasion assay conducted on four cell lines over 2 days. Right: quantification of the spheroid invasion assay. Bars represents the mean ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS non-significant. n = 10 technical replicates of spheroids. Statistical analysis performed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test on day 4 samples of ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines. Scale bar: 500 μm. h Left: in vivo xenograft assay performed using four cell lines. Nude mice and extracted tumors are shown. Top right: quantification of the volume of the extracted tumors. Bottom right: quantification of the weight of the extracted tumors. Bars represents the mean ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS non-significant. n = 10 tumor extracts. Statistical analysis performed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test. ARID1A−/−, ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines were individually compared to WT. i Representative immunohistochemistry images of extracted tumors formed by the four cell lines. Immunostaining was performed using an anti-ARID1A antibody. Scale bars: 10 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We sought to explore if there were detectable nuclear condensates in Ewing’s sarcoma patient tissues resulting from the concentration-dependent ARID1A LLPS that was observed in vitro and inside cells. Using tumor samples from two independent patients with Ewing’s sarcoma, we performed immunohistochemistry and imaged the localization of ARID1A. Surprisingly, ARID1A showed increased expression in Ewing’s sarcoma patient tissue resulting in visible nuclear foci, while normal bone tissue exhibited much lower punctate pattern throughout the nucleus (Fig. 3c). Apart from Ewing’s sarcoma patient tissue, osteosarcoma patient tissue, which exhibits high levels of ARID1A expression, was subjected to staining with an anti-ARID1A antibody (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Our findings revealed that, while the condensates detected in osteosarcoma patient tissue and the osteosarcoma cell line SAOS-2 appeared morphologically smaller and less defined compared to those in Ewing’s sarcoma, a distinct punctate pattern was clearly observed in the nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). These findings indicate a significant upregulation of ARID1A that leads to the formation of nuclear foci in Ewing’s Sarcoma.

Proteins that undergo phase separation inside cancer cells are highly expressed when compared to normal counterpart and possess oncogenic potential28,29. Therefore, we decided to test the oncogenic potential of ARID1A in Ewing’s sarcoma cell line using cell proliferation, invasion and migration assays. We generated ARID1A knockout (ARID1A−/−) A673 cell line using CRISPR-CAS9 gene editing (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We validated that while genetic deletion and transcriptional repression of ARID1A gene suppresses cell proliferation, it does not induce cell toxicity and cellular apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 5b–d). Next, we rescued ARID1A knockout cell line with either WT or LLPS-defective mutant ΔDD. Immunocytochemistry data showed that the endogenous ARID1A formed condensate within WT and ARID1A−/− + WT cells (LLPS positive), whereas ARID1A was diffusive in ARID1A−/− + ΔDD cells (LLPS negative) (Fig. 3d).

In order to show that if these nuclear foci indeed represent phase-separated condensate, we generated GFP knock-in A673 cell line in which GFP is integrated into genomic loci of ARID1A (Supplementary Fig. 6a). We validated that GFP cassette is inserted correctly and that GFP-ARID1A is expressing using various assays (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c). Next, we performed high resolution live imaging to identify nuclear condensate formed by endogenous GFP-ARID1A. We found distinctive foci of GFP-ARID1A inside the nucleus of A673 knock-in cell line (Supplementary Fig. 6d). We further showed that these foci become diffusive upon 1,6-hexanediol treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6e). Next, we performed immunocytochemistry staining BAF subunits while detecting endogenous GFP-ARID1A. We found significant number of BAF subunits co-localized with GFP-ARID1A, indicating enrichment of endogenous BAF subunits inside ARID1A condensate (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Further examination using 3D confocal imaging revealed that these nuclear ARID1A foci detected in Ewing’s sarcoma patient and GFP-ARID1A knock-in A673 cell resembles spherical morphology (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b).

A wound healing assay was then performed using LLPS-positive and LLPS-negative cell lines to assess the motility and ability of each generated cancer cell line to recover the scratch generated on the surface of culture plate. Knockout of ARID1A showed decreased cell migration and motility rate, whereas reconstitution of WT, but not ΔDD mutant, reversed the reduced migration rate (Fig. 3e). To further validate that ARID1A LLPS promotes cancer progression and loss of ARID1A condensate functions antagonistically, spheroid formation assay and spheroid invasion assay were performed to measure the ability of cells to form tumor-like solid structure and to evaluate the invasion property of the spheroids, respectively. At post 4 days of spheroid formation, the volume of spheroid formed by LLPS-positive cells was larger than that of spheroid formed by negative cells. (Fig. 3f). The spheroid invasion assay showed the similar results. (Fig. 3g). Additionally, we conducted spheroid-related assays using cell lines rescued with the PrLD(Y/S) mutant or a mutant with a more restricted number of substitutions, PrLD(Y33/S). As in the case of ΔDD-rescued mutant, this substitution-based phase separation failed to rescue proliferative and invasive phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). Finally, we conducted spheroid-related experiments utilizing the SK-N-MC cell line, which is another Ewing’s sarcoma cell line. Similar to our observations with A673 cell line, we discovered that a decrease in the phase separation of ARID1A resulting from the knockdown (KD) led to a reduction in the oncogenic capabilities of the SK-N-MC cells as well (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d).

Lastly, in order to assess whether these phenomena are recapitulated in vivo, we performed in vivo xenograft by subcutaneously injecting the cells into nude mice. The tumors generated by ARID1A LLPS-positive cells showed notably larger in volume than LLPS-negative cells (Fig. 3h). Immunohistochemistry also confirmed that ARID1A condensate was evident in ARID1A LLPS-positive tumors, but was either diffused or undetectable in ARID1A LLPS-negative tumors (Fig. 3i). Furthermore, we observed an enrichment of the proliferation marker (Ki-67) in ARID1A LLPS-positive tumors, while markers for apoptosis and cellular stress were less detected in LLPS-positive tumors (Supplementary Fig. 9a–c). Taken together, these results indicate that ARID1A exhibits strong oncogenic potential through PrLDs-mediated LLPS in Ewing’s sarcoma.

ARID1A LLPS upregulates cancer-related gene expression and alters chromatin accessibility at EWS/FLI1 binding sites

We next sought to identify the mechanism by which ARID1A LLPS affects oncogenic potential in Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines. Considering the role of ARID1A as a chromatin remodeler, we hypothesized that ARID1A LLPS may activate cancer-related genes by regulating chromatin structure. To identify target genes and cis-regulatory element (referred to hereinafter as cREs) affected by ARID1A LLPS, we performed RNA-seq and ATAC-seq on ARID1A LLPS-positive and negative cell lines. To exclude any genetic background variation occurring while cell line generation, we used five different colonies of ARID1A−/− + WT and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD for genome-wide studies (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). As a result, we found ARID1A LLPS-dependent 1271 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and 9686 dysregulated cREs (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 10c–e). Notably, a higher number of cREs were altered with the increase of chromatin accessibility dependent on ARID1A LLPS (Fig. 4b), seemingly associated with the ability of ARID1A LLPS in the recruitment of numerous BAF subunits. Furthermore, Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated genes are significantly enriched by cancer-related terms such as migration, adhesion, and angiogenesis, consistent with the previous experimental results (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. ARID1A LLPS-dependent altered transcriptome and epigenome.

a A heatmap illustrating expression of DEGs (FDR < 0.05) obtained from the RNA-seq results of WT, ARID1A−/−, five ARID1A−/− + WT, five ARID1A−/− + ΔDD, and ARID1A−/− + PrLD(Y/S) A673 cell lines. The colors indicate normalized gene expression. The dendrogram above the heatmap indicates the hierarchical clustering result of the samples. b Tornado plots illustrating ±800 bp regions from each dysregulated cREs (FDR < 0.05) obtained from ATAC-seq of WT, ARID1A−/−, five ARID1A−/− + WT, five ARID1A−/− + ΔDD, and ARID1A−/− + PrLD(Y/S) A673 cell lines. The colors indicate normalized read counts (left, red) and log2 (LLPS-positive/LLPS-negative) read counts (right, yellow, and cyan). c Top 10 enriched gene ontologies in ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated DEGs. The cancer-related terms are marked with an asterisk. d The rank of transcription factor motifs overrepresented in the ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated cREs. The top two enriched motifs are highlighted. e Tornado plots illustrating published A673 EWS/FLI1 ChIP-seq signal on the ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated cREs, ARID1A LLPS-dependent downregulated cREs, and other randomly selected cREs, respectively. The colors indicate normalized EWS/FLI1 ChIP-seq signal over the input signal.

To dissect underlying mechanism of ARID1A LLPS-dependent cREs dysregulation and its influence on transcription, we sought to identify upstream regulator candidates. To this end, we performed TF motif enrichment analysis for the upregulated cREs. Surprisingly, we revealed that both FLI1 and EWS/FLI1 motif sequences were remarkably enriched in the ARID1A LLPS-upregulated cREs (Fig. 4d)30,31. As EWS/FLI1 is a major driver oncogene in Ewing’s sarcoma, we further examined whether ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated cREs are co-localized with EWS/FLI1 nucleation sites in Ewing’s sarcoma. EWS/FLI1 peaks obtained from A673 Ewing’s sarcoma cells showed remarkable overlap with ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated cREs (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 10f)32. These results indicate that the presence of ARID1A LLPS may facilitate the binding of EWS/FLI1 through alteration of chromatin accessibility, which may exert ARID1A LLPS-dependent oncogene activation. Consistently, we identified ARID1A LLPS-associated genes in gene signature upregulated in Ewing’s sarcoma (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Moreover, gene sets regulated by ARID1A LLPS significantly overlap with genes previously found to be regulated by EWS/ETV (Supplementary Fig. 11b, c and Supplementary Data 1).

Recent studies suggested that Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines show high plasticity33. Therefore, we tested oncogenic potential of ARID1A in different Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines. With published EWS/ETV ChIP-seq data across four Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines (EW1, RDES, SKES1, and SKNMC), we analyzed the EWS/ETVs binding patterns on ARID1A LLPS-dysregulated cREs obtained from A673 (Supplementary Fig. 12a)33. Notably, we observed significant similarity and conservation of binding pattern of EWS/ETVs across the four EwS cell lines compared to A673 (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Furthermore, our analysis revealed that EWS/ETVs from other Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines exhibited enriched binding at the ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated cREs, while EWS/ETV binding was scarce in the downregulated cREs (Supplementary Fig. 12b). This result suggests that ARID1A LLPS is crucial in opening the EWS/ETVs binding sites across EwS cell lines.

To validate that the phase separation of ARID1A influences transcriptional activity of EWS/ETV in various Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines, we first generated ARID1A KD cell lines using another Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines, SK-N-MC and TC106 (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d). Additionally, qRT-PCR was performed to demonstrate the transcriptional regulation of EWS/FLI1-bound genes by ARID1A, revealing a significant decrease in the expression of EWS/FLI1 target genes in the SK-N-MC KD cell line (Supplementary Fig. 12e). To illustrate the dependency of EWS/ERG on ARID1A, we conducted ARID1A KD experiments with subsequent qRT-PCR validation in TC106 cell line. The results indicated that EWS/ERG-bound genes, putative targets of ARID1A LLPS, exhibited decreased gene expression in KD TC106 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 12f). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that ARID1A LLPS is indeed crucial for the oncogenic potential of Ewing’s sarcoma, even across different biological backgrounds.

ARID1A LLPS mediates long-range chromatin contacts between cREs occupied by EWS/FLI1 and oncogenes

Reasoning from the significant alteration of chromatin opening, we hypothesized that ARID1A LLPS-dependent cRE activation may directly regulate the oncogene expression in Ewing’s sarcoma through modification of chromatin architecture. To test this possibility, we performed in situ Hi-C experiments on two ARID1A LLPS-positive and two negative A673 cells (Supplementary Fig. 13a) since cREs are known to regulate target genes over large-genomic distance through long-range chromatin interactions34. Analysis of in situ Hi-C results revealed that substantial portion of the long-range chromatin contacts between the DEGs and the dysregulated cREs were significantly altered (Fig. 5a). We also found that the genes activated by ARID1A LLPS were markedly linked to the upregulated cREs whereas the repressed genes were linked to the downregulated cREs (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 13b), indicating the dysregulated cREs controlled by ARID1A LLPS are closely related to altered gene expression.

Fig. 5. ARID1A LLPS links EWS/FLI1-associated cREs and oncogene activation.

a A heatmap showing significantly (P value < 0.05) altered long-range chromatin contacts between the DEGs and the dysregulated cREs in an ARID1A LLPS-dependent manner. b A barplot illustrating the number of linkages between upregulated DEGs and upregulated, downregulated, and control cREs, respectively. c Left: a tornado plot illustrating published A673 EWS/FLI1 ChIP-seq signal on the upregulated cREs connecting to ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated genes. The colors indicate normalized EWS/FLI1 ChIP-seq signal over the input signal. Middle and right: a heatmap illustrating the upregulated cREs (middle) and the upregulated genes connected to the upregulated cREs (right). The colors indicate normalized read count in the regions and normalized gene expression, respectively. The dashed line indicates linkages between EWS/FLI1-bound upregulated cREs and the upregulated genes. d The normalized Hi-C contact frequencies around the TFAP2B gene promoter are illustrated as a virtual 4C plot. The genome tracks of ATAC-seq and published EWS/FLI1 ChIP-seq signal are shown below. The dashed vertical line indicates the viewpoint of the 4C plot and the asterisk indicates the transcription start site of the TFAP2B gene. The shaded regions highlight the linkages between the TFAP2B gene and the EWS/FLI1-bound upregulated cREs via the proximal colocalization or the altered long-range chromatin contacts. e Odds ratio that an activated gene is included in the cancer-related GO terms shown in Fig. 4c, comparing the genes linked to the upregulated cREs versus unlinked genes (P values for the enrichment of the linked genes versus the unlinked genes: migration = 0.034, cell adhesion = 0.038, two-sided Fisher’s exact test). f A heatmap comparing normalized Hi-C contact frequencies of ARID1A LLPS-positive, negative, and published EWS/FLI1 knockdown (KD) A673 cells, respectively. Only the contacts between EWS/FLI1-bound upregulated cREs and their linked upregulated genes are shown.

Considering that ARID1A LLPS opens EWS/FLI1 binding sites (Fig. 4d, e), we further tested whether EWS/FLI1 binding is associated with cREs that control ARID1A LLPS-dependent upregulated genes. Strikingly, over 70% of the upregulated cREs linked to the activated genes are co-occupied by EWS/FLI1 (Fig. 5c, d). The promoter of TFAP2B, a gene that was previously found to be induced by EWS/FLI1, showed direct contact with ARID1A LLPS-dysregulated cREs (Fig. 5d)35. Such enriched EWS/FLI1 binding was not observed when we examined the downregulated cREs linked to the repressed genes (Supplementary Fig. 13c). Importantly, the genes putatively activated by the upregulated cREs showed strong enrichment in the cancer-related GO terms compared to the other activated genes (Fig. 5e). Our results indicate that EWS/FLI1-bound cREs, dysregulated in cells with ARID1A LLPS, induce expression of oncogenic genes that increase the oncogenic potential of A673 cells.

Since EWS/FLI1 binding has been previously reported to drive long-range chromatin contacts36,37, we examined whether the increased long-range chromatin contacts are mainly driven by EWS/FLI1 or ARID1A LLPS itself. We utilized in situ Hi-C results of EWS/FLI1-depleted A673 cells36 and investigated chromatin contacts between the activated cREs occupied by EWS/FLI1 and linked upregulated genes. Consistent with the previous studies36,37, we observed that the long-range chromatin contacts were generally weakened compared to the ARID1A LLPS-positive WT rescue cells (Fig. 5f). Nevertheless, the contacts were significantly maintained when compared to the ARID1A LLPS-negative cells, suggesting that both EWS/FLI1 binding and ARID1A LLPS are necessary for establishing the oncogenic long-range chromatin contacts (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 13d). Together, our genome-wide analysis suggested that LLPS of ARID1A activates oncogenes in A673 cells via inducing both the opening of de novo EWS/FLI1-bound cREs and the establishing long-range chromatin contacts.

ARID1A interacts with EWS/FLI1 through phase separation

As ARID1A LLPS turned out to induce a significant change in both the chromatin structure and transcriptional profile of EWS/FLI1 target genes, we investigated the direct connection between EWS/FLI1 and ARID1A. Co-immunoprecipitation assay verified a direct interaction between the PrLD1 and PrLD2 regions of ARID1A—responsible for LLPS—and EWS/FLI1 (Fig. 6a). Additionally, ARID1A WT that is capable of LLPS showed the ability to bind EWS/FLI1, whereas the PrLD Y/S mutant failed to bind (Fig. 6a), suggesting that the interaction between ARID1A and EWS/FLI1 relies on LLPS. Furthermore, the in vitro droplet assay showed that EWS/FLI1 forms co-condensate with ARID1A WT (Fig. 6b). To further probe the effect of ARID1A LLPS on EWS/FLI1 subcellular localization, we performed immunostaining of endogenous EWS/FLI1 for both ARID1A LLPS-positive and negative cells. In ARID1A LLPS-positive cells, there was a formation of nuclear condensates of both ARID1A and EWS/FLI1, which were observed to co-localize. However, in ARID1A LLPS-negative cells, the number of EWS/FLI1 condensates decreased significantly (Fig. 6c, d)38–40.

Fig. 6. ARID1A directly interacts with EWS/FLI1 through phase separation.

a Binding site mapping of FLAG-EWS/FLI1 and GFP-ARID1A recombinant proteins by co-immunoprecipitation assay. Tested proteins include PrLD1, ARID, PrLD2, Pfam, PrLD(Y/S) mutant, and full-length ARID1A. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. b Confocal image of an in vitro co-droplet assay demonstrating colocalization of purified GFP-ARID1A and mCherry-EWS/FLI1. Scale bars: 5 μm. The representative images supported by the relevant statistics have been chosen upon three independent preparations with similar outcomes. c Representative confocal images of ARID1A−/− + WT and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines immunostained with anti-FLI1 and anti-ARID1A antibodies. Scale bars: 5 μm. d Quantification of number of FLI1 puncta per cell lines in (c). n = 32 technical replicates of cells; bars represents mean ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS non-significant. Statistical analysis performed using a two-tailed t-test. ARID1A−/−, ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines were individually compared to WT. e ChIP assays performed on EWS/FLI1-bound enhancers in ARID1A−/− + WT and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines using antibodies against IgG, FLI1, H3K27ac, and SMARCC1. Bars represents mean ± SEM; n = 3 technical replicates; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS non-significant. Statistics by two-tailed t-test using ARID1A−/− + WT, and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines as comparison. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further performed ChIP assay using anti-EWS/FLI1, anti-H3K27ac, and anti-SMARCC1 antibodies in the A673 cell lines. We targeted cREs of previously reported EWS/FLI1 induced genes where chromatin accessibility is regulated by ARID1A LLPS33,41,42. In all cREs we tested, chromatin occupancy of EWS/FLI1 and SMARCC1 significantly decreased upon loss of ARID1A LLPS, along with decreased H3K27ac, active enhancer histone marker (Fig. 6e). Taken together, our data suggest that nuclear condensates of ARID1A navigate to EWS/FLI1 target genes through co-phase separation with EWS/FLI1 and subsequently compartmentalize BAF complex to form active chromatin remodeling hub and promote Ewing’s sarcoma (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Schematic representation of ARID1A phase separation.

ARID1A undergoes phase separation at EWS/FLI1-bound enhancers and forms condensates, which compartmentalize BAF complex subunits, leading to chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation of oncogenes. Loss of ARID1A phase separation results in chromatin closure and reduced transcription of oncogenic target genes, leading to a significant decrease in the oncogenic potential of Ewing’s sarcoma. This figure was created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License.

Discussion

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of phase separation in various biological processes (BPs), such as RNA processing, autophagy, and cell signaling43–45. Phase-separated condensates form molecular “hot spots” where molecules with corresponding functionalities get drawn in and set up to execute certain activities. Inside the nucleus, transcriptional condensates with a phase-separated feature demonstrate liquid-like properties and adjust gene expression accordingly. Given that these droplets are an important element of core cellular processes, any irregularities in them could be correlated to maladies, especially cancer.

Our study offers clarity on the way ARID1A, with its phase-separation property, advances the oncogenic state of Ewing’s sarcoma. ARID1A is composed of PrLDs which have tyrosine residues that act as sticky motifs to enable various interactions and bring about phase separation. Additionally, ARID1A contains a structured Pfam homology domain that directly binds to components of the BAF complex. Surprisingly, phase separation of ARID1A does not interrupt with its ability to connect to BAF molecules, however, these PrLDs are central to compartmentalizing BAF molecules into condensates and creating chromatin remodeling hubs. Samples from Ewing’s Sarcoma patients evidenced the presence of visible ARID1A condensates. Disruption of ARID1A LLPS in a cancer cell line weakened the effects of Ewing’s sarcoma’s oncogenic potential, indicating that the condensates initiated by ARID1A play a role in the cancer phenotype. Consolidation of genome-wide studies, including ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and Hi-C, demonstrated that the phase separation of ARID1A specifically enhances chromatin accessibility at EWS/FLI1-bound cREs, leading to changes in chromatin architecture and subsequent transcriptional alterations at oncogenic target genes.

Given the capacity of ARID1A to undergo phase separation, this protein may form condensates in cellular settings beyond Ewing’s sarcoma. The phase separation of ARID1A in Ewing’s sarcoma is indispensable for its engagement with EWS/FLI1, which provides access to EWS/FLI1-linked enhancers and in turn induces chromatin remodeling. ARID1A gains access to enhancers and promoters once it partners with a variety of transcription factors, being AP1, ERα, and FOXA115,16. In this fashion, it can be hypothesized that in relevant biological conditions/context, ARID1A could possibly undergo phase separation with distinct transcription factors at chromatin for activation of the gene transcription. It is noteworthy that ARID1A is presented with a high rate of somatic mutations in many diseases, contributing to the accumulation of a significant number of mutations in its PrLDs46,47. Therefore, it can be speculated that mutations occurring at PrLDs, connected with the disease, might alter the phase separation properties of ARID1A and/or its connection with the transcription factors, thus becoming an important factor in the pathogenesis of human malignancies.

Several transcription factors arising from chromosome rearrangements and translocations, similar to the case of Ewing’s sarcoma, have been seen to hijack the BAF complex in cancer. Those transcription factors include EWS/FLI1, TMPRSS/ERG, MN1, FUS/DDIT3, and ENL48–52. Interestingly, EWS/FLI1, MN1, FUS/DDIT3, and ENL all undergo LLPS within cancer cells48,50,51,53. Additionally, a prior study indicated that EWS/FLI1 fusion protein interacts with the BAF complex via its PrLD domain48. In line with this, our observations reveal co-condensation between ARID1A and EWS/FLI1, facilitated by mutual interactions of their PrLDs (Fig. 6a, b). Consequently, it is plausible that oncogenic factors equipped with PrLDs and IDR might co-opt the BAF complex by directly interacting with ARID1A. Although the exact mechanism of recruitment and the nature of the interaction between the BAF complex and oncogenic factors are not fully understood, our results suggest that ARID1A may serve as a connecting link between the oncogenic factor and the BAF chromatin remodeling complex.

Previous attempts have been made to pharmacologically inhibit EWS/FLI1, a major driver of sarcoma, using small molecules. The small molecule trabectedin was found to prevent the localization of EWS/FLI1 within the nucleoplasm and disrupt its function54. YK-4-279 could block the binding of RNA helicase A with EWS/FLI1, leading to reduced proliferation of Ewing’s sarcoma cells55. Nevertheless, transcription factors usually bind extremely tightly to target DNAs and do not feature domains in which small molecules can act on, indicating they are resistant to becoming targeted by potential inhibitor. As a result, more researchers are striving to locate and create safe drugs targeting transcriptional cofactors that are linked indirectly to DNA and move around the genome. High-throughput screening has identified an inhibitor of ARID1A, known as BD98, which can be used to target the ARID1A-specific BAF complex56. Administering BD98 to embryonic stem cells and T cells can effectively simulate the impact of ARID1A depletion, causing a reduction in the ARID1A-oriented transcriptional program56,57. Furthermore, this inhibitor has been employed, along with an ATR inhibitor, to cause cell death in colorectal carcinoma cells, illustrating its potential as a cancer therapeutic58. Targeting both ARID1A and its PrLDs could be a promising strategy to restrict EWS/FLI1 from attaching to regulatory enhancers and prevent chromatin contact in the vicinity of oncogenes, making ARID1A PrLDs a potential therapeutic target for Ewing’s sarcoma. Combining an ARID1A inhibitor like BD98 with an inhibitor for EWS/FLI1 could mount a more potent form of therapy for patients. Another group has discovered sequence grammar within the IDRs of ARID1A and ARID1B that governs their phase separation within the cell. This condensation of ARID1A/ARID1B creates a distinctive network of protein–protein interactions critical for chromatin navigation and gene activation. Additionally, perturbations in the IDR of ARID1B associated with human diseases have been identified, indicating that the IDR could be a potential therapeutic target region59. These results spotlight the potential of future drug developments, such as targeting ARID1A PrLDs to inhibit abnormal activation of pathogenic genes and halt disease progression.

Methods

Reagent

The following commercially available antibodies were used: anti-ARID1A (ab182560), anti-SMARCC1 (ab172638), anti-FLI1 (ab133485), anti-SMARCE (ab70540), anti-H3K27ac (ab4729) (Abcam); anti-Flag (F3165), and anti-β-actin (A1978), anti-ARID1A (AMAb91192) (Sigma-Aldrich); anti-GFP (sc-9996), anti-SMARCB (sc166-165), anti-SMARCD (sc-135843) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-SMARCA2 (26613-1-AP) (Proteintech). Following commercially available fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21206) and Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-mouse IgG (A21203) (Invitrogen). We used antibodies recommended by the manufacturer for the species and application.

Cell culture and transfection

The A673, SK-N-MC cell lines were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank. HEK293T cell was obtained from ATCC. TC106 was kindly provided by T.G.P.G. Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination and were routinely treated with BM-cyclin. A673 cells were cultured with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. HEK293T cell line was grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Transfection was performed using PEI (Sigma-Aldrich). The cell lines were STR authenticated by STR profiling.

Generation of genetically modified cell line

Ewing’s sarcoma cell line A673 was genetically modified using the CRISPR-CAS9 system. A guide RNA (sequence: GGGGCCTGGAGCCCTACGCG) targeting the first exon of ARID1A was cloned into a px330 vector. Transfected cells were then cultured in a 99-well plate at one cell per well. Single-cell colonies were grown, and genotyping was performed. Cells with a complete loss of ARID1A protein expression, as confirmed via western blot, were chosen as ARID1A KO A673. For ARID1A rescue A673 KO cells, the pLenti-puro-ARID1A (plasmid#39478, Addgene) plasmid was transduced into ARID1A KO A673 cells using lentiviral particles. The transduced cells were selected using puromycin. Selected cells were then plated in a 99-well plate at one cell per well. Single-cell colonies were genotyped several times until the ARID1A levels of rescue cells were comparable to those of their WT counterparts. For the generation of ARID1A PrLD(Y/S) and ARID1A ΔDD-rescued A673 ARID1A KO cells, pLenti-puro-ARID1A PrLD(Y/S) and pLenti-puro-ARID1A ΔDD were each transduced into KO cells via lentiviral particles. The transduced cells were selected using puromycin and added into a 99-well plate at one cell per well. Single-cell colonies were genotyped several times until sufficient ARID1A PrLD(Y/S) or ARID1A ΔDD expression was observed.

Establishment of EGFP-tagged ARID1A knock-in A673 cell line

For transfection, A673 cells were rinsed with DPBS (Gibco) and detached with 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA (LS015-10, WELGEN). After the detachment of A673 cells, Trypsin–EDTA was inactivated by adding RPMI 1640 (HyClon) with 20% FBS. A673 cells were washed with DPBS for two times. Washed A673 cells were counted and resuspended by Resuspension Buffer R in Neon Transfection System μl 100 Kit (MPK10096, Invitrogen) to concentration of 1 × 107 cells in 1 ml. Three micrograms of Cas9 vector, 1 μg of gRNA vector targeting ARID1A, and 2 μg of EGPF-ARID1A knock-in donor plasmid were added to 100 μl of resuspended A673 cells. Plasmid and A673 cell mixture were electroporated by Neon Transfection System with 1650 volts, 10 ms pulse length, and 3 pulses condition following the supplier’s instructions. After 96 h from transfection, EGFP + A673 cells were sorted with Flow Cytometer (SH800S, SONY). Sorted cells were seeded into 96 well cell culture plate for single-cell isolation.

Immunofluorescence staining and live-cell imaging

Cells were seeded onto a confocal dish and fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBS-T) at room temperature for 10 min. Blocking was performed with 3% bovine serum in PBS-T for 1 h. For staining, cells were incubated with primary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h, followed by incubation with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies and DAPI for 1 h. VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium was used for mounting, and cells were visualized under a confocal microscope (Zeiss, LSM700). For live-cell imaging, 293T cell was transfected with the GFP-ARID1A construct a day before and imaged. For hexanediol treatment, 293T cells were seeded in a confocal dish, and the nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. Six percent of 1,6-hexanediol was directly added to cells under a microscope, and images were continuously acquired.

FRAP

FRAP was performed using a Zeiss LSM700 microscope with a 594 nm laser. Bleaching was performed over at rbleach = 1 μm using 100% laser power. Images were acquired every second. For quantification, multiple sets of FRAP experiments were performed on independent GFP-ARID1A condensates. The same interval of image acquisition was applied for each set of experiments. The fluorescence intensity was acquired by Zen program (Zeiss). The relative fluorescence intensity was calculated using the initial fluorescence intensity as a reference point. The mean and standard deviation were subsequently calculated.

Protein expression and purification

Prokaryotic plasmid containing His-GFP-tagged recombinant protein (PrLD1, ARID, PrLD2, Pfam) or His-mCh-EWS/FLI1 were transformed into M15(pREP) cells. After induction with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside, the bacterial pellet was lysed in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 1 % Triton X-100). The lysate was then sonicated and centrifuged. The supernatant was incubated overnight with Talon beads. The bead-protein complex was washed with lysis buffer three times and eluted using elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 200 mM imidazole, and 1 mM DTT). Eluted protein was assessed via Coomassie staining, and a single protein band was confirmed. For purification of GFP-ARID1A, GFP-ARID1A PrLD(Y/S) and GFP-ARID1A ΔDD, HEK293T cells were used for transfection. GFP-tagged proteins in cell lysates were enriched using GFP-Trap magnetic bead (Chromotek). The protein-bead conjugate was washed stringently for five times using high salt wash buffer and eluted using acidic elution buffer with a composition suggested by manufacturer. The eluted protein was immediately neutralized using neutralization buffer. The size and purity of the eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

Droplet-formation assay

In vitro droplet-formation assay was performed as previously described60. Briefly, recombinant proteins were concentrated and desalted using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (30K MWCO, Millipore). Eluted proteins were diluted to varying concentrations in phase separation buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10% glycerol, 10 % PEG8000, and 1 mM DTT. The protein solution was loaded onto a confocal dish and imaged using a Zeiss LSM700 microscope. Droplet size was quantified by measuring the circumference of droplets using a Zen image viewer.

Characterization of saturation concentrations of ARID1A variants

To measure the saturation concentrations of various ARID1A variants, we used HEK 293 cells transfected with corresponding GFP-tagged ARID1A variants 24 h prior to imaging. The nuclear boundaries of cells were detected manually. For individual cells, average fluorescence intensities within nucleus were measured using image processing and analysis program NIH Image J and the presence of condensates of ARID1A variants was checked.

Corelet colocalization experiments

ARID1A KO A673 cells stably expressing PrLD1 or PrLD1-pfam Corelet constructs were seeded onto a confocal dish and transfected with plasmids of individual BAF complex components 24–48 h prior to imaging. Media was exchanged 8 h after transfection. To prevent any unwanted pre-activation of Corelets, the mCherry channel was used to locate cells expressing proper levels of Corelet constructs. Once located, blue light activation was performed simultaneously with data acquisition through sequential imaging of GFP and mCherry channels. The initial images represented conditions prior to blue light activation. Dual color imaging was performed every 3 s for 15 min. Line profiles were obtained using image processing and analysis program NIH Image J and normalized with the average intensity of the dilute phase. Moving averages were applied when necessary.

ARID1A protein expression level across cancer types

ARID1A protein expression levels were acquired from the raw data of a previously published proteome analysis27. Briefly, 375 cell lines were grouped by cancer type, and ARID1A expression levels were determined for each type. The resulting individual, average and standard deviation of protein expression value of ARID1A is presented as a box plot.

Wound healing assay

Wound healing scratching motility assay was performed in WT, ARID1A−/−, ARID1A−/− + WT and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines. Cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates and cultured until they reached confluence. Cells were scratched with a 200 μl micro-pipette tip and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Photomicrographs of the closed gap were captured at 0, 24, and 48 h using JuLI Stage Real-time live-cell imaging system (NanoEntek; http://www.NanoEntek.com). Migration distance of the cells was quantified by distance of gap using wound healing analysis package provided by JuLI Stage software. Values are expressed as means ± SEM.

Spheroid formation and spheroid invasion assays

Spheroid formation assay was performed in WT, ARID1A−/−, ARID1A−/− + WT and ARID1A−/− + ΔDD A673 cell lines. Two thousands counted cells from each cell line were pipetted into Ultra-Low Attachment 96 well plate (Corning Costar). Subsequently, the plate was centrifuged at low speed for 10 min and sequestered cells were visualized under microscope. For spheroid formation assay, cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before imaging. Photomicrographs of the spheroid growth were captured at each day until day 4 using JuLI Stage Real-time live-cell imaging system (NanoEntek; http://www.NanoEntek.com). Spheroid volume was quantified by automated spheroid analysis package provided by JuLI Stage software. For spheroid invasion assay, next day, matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) was added directly to the media containing the spheroid. Matrigel was solidified inside the incubator. Photomicrographs of the spheroid growth were captured at 0, 24, and 48 h using JuLI Stage Real-time live-cell imaging system (NanoEntek). Spheroid volume was quantified by automated spheroid analysis package provided by JuLI Stage software.

Immunohistochemistry

To detect ARID1A expression in human tissue samples, paraffin-embedded human normal bone tissue (US Biomax, BO244g) and Ewing’s sarcoma tissue (US Biomax, T263, T264a) were deparaffinized, hydrated, and heated in retrieval buffer (10 mM sodium citrate [pH 6.0]) over 10 min for antigen retrieval, and then incubated with ARID1A antibodies (Abcam, ab182560, 1:200). Subsequently, tissues were incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies and DAPI for 1 h. VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium was used for mounting, and tissues were visualized under a confocal microscope (Zeiss, LSM700). Patient age, gender, and diagnosis information are available on the company’s website:

Xenograft

For tumor formation in vivo, 107 cells with equal volume of matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) were injected subcutaneously at the left and right flank bilaterally into 6-week-old athymic nu/nu female mice (Charles River). Tumors were measured weekly, and the experiment was terminated at week 5. A total of 10 tumors from 5 mice were excised for each cell line and weighed. Statistical differences in tumor weights were determined by Wilcoxon signed rank test using the Graphpad prism. These experiments were carried out with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Seoul National University. Tumor sections were stained and imaged as described above. Image quantification was performed using image processing and analysis program NIH Image J.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq)

RNA was extracted from 106 harvested cells with a Nucleospin RNA XS kit (Macherey-Nagel, MN740902). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep kit (Illumina, 20020594). RNA-seq libraries were sequenced in a 100 bp paired-end mode, with a MGI DNBSEQ-G400 system.

RNA-seq analysis

Reads were aligned to the reference genome (hg38) using STAR software v2.7.8a with default parameters61. The gene counts were quantified with RSEM62. The DEGs were obtained using DESeq2 with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.0563. Among the obtained DEGs, only genes annotated as protein-coding genes with confidence levels 1 and 2 were used. GO analysis was performed using DAVID with GO BP64.

ATAC-seq analysis

ATAC-seq libraries were prepared for sequencing using Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1 Enzyme and Buffer Kits (#20034197, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The adapter sequences were trimmed out using Cutadapt65. The trimmed paired-end sequences were mapped to the human reference genome hg38 using bowtie 2 with parameters “—very-sensitive –X 1000 –dovetail”66. The reads with poor mapping quality (MAPQ < 30) and the reads mapped to the mitochondrial genome were discarded. The potential PCR duplicates were marked using MarkDuplicates of Picard, and the reads were shifted using the alignmentSieve function of deeptools with the “—ATACshift” parameter67. The accessible regions were defined using MACS2 narrow callpeak, keeping duplicates with a q value cutoff of 0.01. For downstream data analyses, we merged accessible regions obtained from all samples. ARID1A LLPS-dependent dysregulated cREs were identified by applying DESeq2 to the read counts on the merged accessible regions (FDR < 0.05)63. Tornado plots of ATAC signal were generated using deeptools bamCoverage and computeMatrix67. Enriched motifs of the dysregulated cREs were identified by using HOMER findMotifsGenome knownResults with the parameters “-size given”68. PCA analysis of ATAC-seq was conducted on the log2-normalized top 500 highly variable peaks using DESeq263. For visualization into genome track, ATAC reads were depth-normalized among the samples.

In situ Hi-C

In situ Hi-C was performed on two ARID1A LLPS-positive (ARID1A−/− + WT 2 and 3) and two LLPS-negative (ARID1A−/− + ΔDD 2 and 4) cells. For each sample, 106 cells were harvested and crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 9 min at RT in 10 ml PBS and 100 µl FBS. Cells were treated with 250 mM glycine for 5 min at RT and 15 min on ice, to quench the crosslinking. The cells were then lysed with 10 nM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, and 0.2% IGEPAL CA630. The crosslinked chromatin was digested with 100 U MboI, labeled with biotin-14-dTCP, and ligated with T4 DNA Ligase. The ligated samples were reverse-crosslinked with 2 µg/µl proteinase K, 1% SDS, and 500 mM NaCl overnight at 65 °C. The DNA fragments were collected with Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, A63881) and sonicated using Covaris S220 into 300~400 bp. The biotin-labeled DNA was pulled down with Dynabeads MyOne streptavidin T1 beads (Invitrogen, 65602) with thorough washings. DNA end repair, un-ligated ends removal, adenosine addition at 3′ end (NEB, M0212), ligation of Illumina indexed adapters (NEB, M2200), and PCR amplification were performed to generate Hi-C libraries. The generated libraries were sequenced in 100 bp paired-end mode using MGI DNBSEQ-G400.

In situ Hi-C analysis

Published A673 in situ Hi-C data upon EWS/FLI1 depletion were downloaded from GEO database under accession number GSE185125. For both performed and downloaded in situ Hi-C data, the sequenced reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg38) using BWA-mem. Chimeric reads spanning multiple sites of the genome were filtered out. The reads with poor mapping quality (MAPQ < 10) and putative self-ligated reads (genome distance <15 kb) were discarded. Potential PCR duplicates were marked using MarkDuplicates of Picard69. The reads were then assigned into 40 kb genomic bins to generate a 40 kb Hi-C contact map. To consider possible genome-dependent bias, coverage-based contact map normalization was performed with covNorm70. To investigate altered chromatin contacts between the DEGs and the dysregulated cREs mediated by ARID1A LLPS, we collected the normalized Hi-C contacts linked to all pairs of possible DEGs and dysregulated cREs within 2 Mb from LLPS-positive and negative samples. Quantile normalization of the collected contacts was performed among the samples to normalize depth differences. The contacts were then log-transformed and used as input to LIMMA71. We defined significantly increased/decreased contacts by LLPS of ARID1A using the limma-trend algorithm (P value < 0.05).

Gene–cRE linkage

To investigate the subset of DEGs that are directly regulated by the ARID1A LLPS-dysregulated cREs, we defined the potential regulatory linkage between the DEGs and the dysregulated cREs. To account for both proximal and long-range gene–cRE interactions, we considered each gene–cRE pair as linked if they are co-localized (<40 kb) or if chromatin contact significantly increased between the two elements upon the LLPS of ARID1A in 40 kb resolution.

ChIP assay

Cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Next, 1.25 M glycine was used for quenching and cells were washed two times using PBS. The cells were then scraped and lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, supplemented with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Cells were sonicated with the sonication condition of 70 amplitude, 30 min process time, 30 s ON and 30 s OFF. After sonication, lysates were centrifuged and supernatant was taken. Chromatin extracts containing DNA fragments with an average of 250 bp were then diluted ten times with dilution buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) with complete protease inhibitor cocktail and subjected to immunoprecipitations overnight at 4 °C. Conjugates were further incubated using BSA blocked 40 μl of protein A/G Sepharose for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed with TSE I buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) and 150 mM NaCl), TSE II buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) and 500 mM NaCl), buffer III (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) and 1 mM EDTA), three times TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA) and eluted in elution buffer (1% SDS and 0.1 M NaHCO3). Reverse-crosslinking was performed by incubating the eluted DNA in 65 °C overnight. RNase and Proteinase K were treated. Lastly, DNA was purified using MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). Purified DNA was used for qPCR analysis using primer targeting each enhancer regions of target genes (Supplementary Data 2).

ChIP-seq data analysis

Published A673 EWS/FLI1 ChIP-seq and input data were downloaded from GEO database under accession number GSE165783. Reads were mapped to the reference genome (hg38) using BWA-mem and the potential PCR duplicates were marked using MarkDuplicates of Picard69. The reads with poor mapping quality (MAPQ < 10) were discarded. EWS/FLI1 peaks were called using MACS2 narrow callpeak, with q value a cutoff of 0.01. The cREs are considered “EWS/FLI1-bound” if there is an overlap between the cRE and the EWS/FLI1 peak. The tornado plots of EWS/FLI1 on the cREs were generated with deeptools computeMatrix function with an option “scale-regions”63.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Seoul National University Research Grant in 2019 to S.H.B., Y.S. and M.C., and by Creative Research Initiatives Program (Research Center for Epigenetic Code and Diseases, 2017R1A3B1023387) to S.H.B., RS-2023-00211612 to Y.S., and NRF-2023R1A2C3002773 to I.J. from the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government. Schematics were created with Biorender.com.

Author contributions

I.J., Y.S., and S.H.B. designed and directed the integrated phase separation and genomics analysis. Y.R.K., D.H.L., C.R.K., and H.K. performed cell biology and biochemistry experiments. J.C. performed cloning experiments for plasmid construction. Y.S.Y. analyzed CCLE data. C.K. and H.J.L. designed and performed Corelet experiments and imaging. J.J. performed RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and Hi-C experiments. J.J. and M.C. performed bioinformatics analysis. Y.R.K. and I.H. prepared human tumor sections and mouse tumor tissue samples. J.P. and S.B. designed and generated GFP-tagged ARID1A knock-in cell line. K.H. and T.G. provided Ewing’s sarcoma cell line and performed transcription profiling.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Javier Alonso, Tom Owen-Hughes and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Next-generation sequencing datasets including RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and Hi-C used in this study are deposited in the NCBI GEO under the accession number GSE234239. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yong Ryoul Kim, Jaegeon Joo.

Contributor Information

Inkyung Jung, Email: ijung@kaist.ac.kr.

Yongdae Shin, Email: ydshin@snu.ac.kr.

Sung Hee Baek, Email: sbaek@snu.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51050-0.

References

- 1.Bhowmik, D. et al. Cooperative DNA binding mediated by KicGAS/ORF52 oligomerization allows inhibition of DNA-induced phase separation and activation of cGAS. Nucleic Acids Res.49, 9389–9403 (2021). 10.1093/nar/gkab689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin, E. W. et al. Valence and patterning of aromatic residues determine the phase behavior of prion-like domains. Science367, 694–699 (2020). 10.1126/science.aaw8653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, J.-M., Holehouse, A. S. & Pappu, R. V. Physical principles underlying the complex biology of intracellular phase transitions. Annu. Rev. Biophys.49, 107–133 (2020). 10.1146/annurev-biophys-121219-081629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung, J.-H. et al. A prion-like domain in ELF3 functions as a thermosensor in Arabidopsis. Nature585, 256–260 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2644-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang, Y. et al. A prion-like domain in transcription factor EBF1 promotes phase separation and enables B cell programming of progenitor chromatin. Immunity53, 1151–1167 (2020). 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang, S., Fagman, J. B., Chen, C., Alberti, S. & Liu, B. Protein phase separation and its role in tumorigenesis. Elife9, e60264 (2020). 10.7554/eLife.60264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberti, S., Gladfelter, A. & Mittag, T. Considerations and challenges in studying liquid-liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell176, 419–434 (2019). 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu, Y. et al. Fragment-based discovery of AF9 YEATS domain inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 3893 (2022). 10.3390/ijms23073893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan, L. et al. Impaired cell fate through gain-of-function mutations in a chromatin reader. Nature577, 121–126 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-019-1842-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solman, M., Woutersen, D. T. & den Hertog, J. Modeling (not so) rare developmental disorders associated with mutations in the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.10, 1046415 (2022). 10.3389/fcell.2022.1046415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu, G. et al. Phase separation of disease-associated SHP2 mutants underlies MAPK hyperactivation. Cell183, 490–502 (2020). 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng, L., Li, E.-M. & Xu, L.-Y. From start to end: phase separation and transcriptional regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gene Regul. Mech.1863, 194641 (2020). 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2020.194641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn, J. H. et al. Phase separation drives aberrant chromatin looping and cancer development. Nature595, 591–595 (2021). 10.1038/s41586-021-03662-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, X. et al. Nuclear condensates of YAP fusion proteins alter transcription to drive ependymoma tumourigenesis. Nat. Cell Biol.25, 323–336 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]