Abstract

Purpose

The association between fluoroquinolone intake and Achilles tendinopathy (AT) or Achilles tendon rupture (ATR) is widely documented. However, it is not clear whether different molecules have the same effect on these complications. The purpose of this study was to document Achilles tendon complications for the most prescribed fluoroquinolones molecules.

Methods

A literature search was performed on Pubmed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science databases up to April 2023. Inclusion criteria: studies of any level of evidence, written in English, documenting the prevalence of AT/ATR after fluoroquinolone consumption and stratifying the results for each type of molecule. The Downs and Black’s ‘Checklist for Measuring Quality’ was used to evaluate the risk of bias.

Results

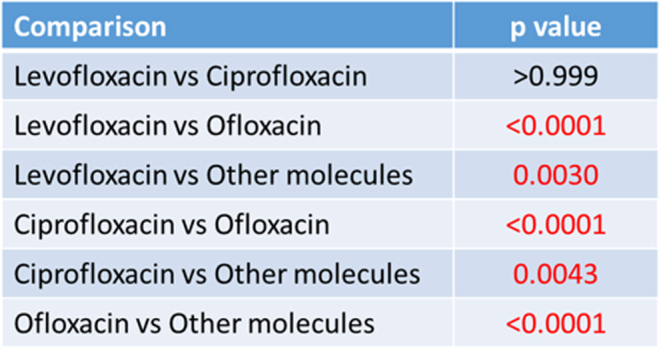

Twelve studies investigating 439,299 patients were included (59.7% women, 40.3% men, mean age: 53.0 ± 15.6 years). The expected risk of AT/ATR was 0.17% (95% CI: 0.15–0.19, standard error (s.e.): 0.24) for levofloxacin, 0.17% (95% CI: 0.16–0.19, s.e.: 0.20) for ciprofloxacin, 1.40% (95% CI: 0.88–2.03, s.e.: 2.51) for ofloxacin, and 0.31% (95% CI: 0.23–0.40, s.e.: 0.77) for the other molecules. The comparison between groups documented a significantly higher AT/ATR rate in the ofloxacin group (P < 0.0001 for each comparison). Levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin showed the same risk (P = n.s.). The included studies showed an overall good quality.

Conclusion

Ofloxacin demonstrated a significantly higher rate of AT/ATR complications in the adult population, while levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin showed a safer profile compared to all the other molecules. More data are needed to identify other patient and treatment-related factors influencing the risk of musculoskeletal complications.

Keywords: Achilles tendinopathy, Achilles tendon rupture, ciprofloxacin, fluoroquinolones, levofloxacin, ofloxacin

Introduction

The association between tendon disorders and fluoroquinolone use is widely documented in the literature (1). Achilles tendinopathy (AT) is a frequently observed complication that can lead to Achilles tendon rupture (ATR) (2). The risk of AT or ATR during fluoroquinolone therapy accounts for 0.1–0.4% (3, 4, 5). The pathophysiology of tendon damage is not clear and is possibly related to an induced imbalance in fibroblast activity, alteration of transmembrane proteins, and oxygen radicals’ production (6). Quinolone-induced AT usually develops in the first 30 days after the first administration and is often painful and long-lasting, significantly reducing a patient’s quality of life (7).

Accordingly, over the past decades, the growing evidence from post-marketing analysis, adverse drug reaction reports, and observational studies has led to an increased caution in quinolone indications and prescriptions (8). Two subsequent warnings from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (9, 10) recommended the use of fluoroquinolones only when no other treatments are available. Also, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (11) introduced new restrictions on quinolone prescriptions. Nevertheless, many patients require systemic fluoroquinolones, and these antibiotics are commonly used to treat respiratory, urinary, and gastrointestinal infections (12). In addition, the occurrence of antibiotic-multiresistant bacteria has been known for years (13) and often requires the use of systemic antibiotic combination therapy, including fluoroquinolones, in both adult and pediatric populations (14, 15). Thus, it is of paramount importance to identify the specific risks associated with different molecules (7), to guide informed decisions of physicians considering using fluoroquinolones.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to quantify and stratify the risk of AT and ATR of fluoroquinolone treatments for each molecule, to identify if there are ‘safer’ fluoroquinolone molecules showing a lower prevalence of these relevant complications.

Materials and methods

Literature search

A review protocol was created based on the preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (16, 17). The study was registered on PROSPERO (ID CRD42022366531). A literature search was performed in four bibliographic databases (PubMed, Web Of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library) up to April 4, 2023. The following research terms were used: ‘(tendon OR tendinopathy OR tendinitis OR tendinosis OR disorder OR injury OR rupture OR treatment) AND (achilles) AND (quinolon* OR fluoroquinolon* OR ciprofloxacin OR fleroxacin OR enoxacin OR norfloxacin OR ofloxacin OR levofloxacin OR perfloxacin OR moxifloxacin OR sparfloxacin OR gatifloxacin OR grepafloxacin OR lomefloxacin OR rosoxacin)’. Inclusion criteria were studies addressing AT and/or ATR as side effects secondary to fluoroquinolone therapy. Only studies written in English were included. Case reports or case series describing fewer than five cases and articles in languages other than English were excluded. Preclinical studies, ex vivo studies, and review articles were also excluded.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (FMA and MS) screened all the articles’ titles and abstracts to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria. After the first screening, the articles that met the inclusion criteria were evaluated for full-text eligibility. Any disagreement between the two reviewers (FMA and MS) was solved by discussion, consulting a third reviewer (AS) in order to reach a consensus. When the studies screened did not stratify fluoroquinolone intake and AT complications by type of molecule, the authors of the original publications were contacted using the address for correspondence to obtain further information. Data were independently extracted using a preconceived data extraction form in Excel (Microsoft). The following data were extracted: authors, year of publication, type of study, number of patients, mean age, type of molecules used, number of AT and ATR, and other complications.

Assessment of risk of bias and quality of evidence

Downs and Black’s ‘Checklist for Measuring Quality’ was used to evaluate the risk of bias and quality of the included articles (18). It contains 27 yes-or-no questions across five sections. The Downs and Black’s tool assigns each study an excellent ranking for scores ≥ 26, good for scores from 20 to 25, fair for scores between 15 and 19, and poor for scores ≤14 points. The five sections include questions about the overall quality of the study (ten items), the ability to generalize findings of the study (three items), the study bias (seven items), confounding and selection bias (six items), and the power of the study (one item). Assessment of risk of bias and quality of evidence was completed independently for all outcomes by two reviewers (EAT and MR). Any disagreement was solved with a third reviewer (AS) by discussion.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis and the forest plot were carried out by an independent professional statistician. Due to very low prevalence values, the Freeman–Tukey double-arcsine transformation (19) was used to provide pooled rates across the studies. A statistical test for heterogeneity was initially conducted with the Cochran Q statistic and I2 metric, and the presence of significant heterogeneity was considered with I2 values ≥25%. When no heterogeneity was found with I2 < 25%, a fixed-effect model based on the Mantel–Haenszel method was used to estimate the expected values and 95% CIs; otherwise, a random-effect model was applied, and an I2 metric was evaluated for the random effect to assess the correction of heterogeneity. Comparison between prevalence rates was performed with the chi-square test. All statistical analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and the MetaXL add-in.

Results

Literature search

The literature search results are summarized in Fig. 1 and briefly described below.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart. Out of 981 studies, 12 were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Systematic review results

A total of 981 articles were retrieved. After removing duplicates and screening the titles, abstracts, and full-texts, 12 studies (439 299 patients) were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30). Among them, there was one randomized controlled trial, one prospective study, eight retrospective studies, and two case–control studies. Details of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the included studies.

| Study | Year | Study design | Patients, n | Mean age, years | Mean treatment duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |||||

| van der Linden et al. (27) | 1999 | RS | 1841 | 664 | 1177 | 53 | 9 days |

| Chhajed et al. (20) | 2002 | RS | 72 | NR | NR | 52.9 | NR |

| van der Linden et al. (29) | 2002 | RS | 6402 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| van der Linden et al. (26) | 2003 | CC | 66 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Seeger et al. (23) | 2006 | CC | 837 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Noel et al. (14) | 2007 | PS | 1340 | 724 | 616 | 3.2 | 10 days |

| Senneville et al. (24) | 2007 | RS | 84 | NR | 52.4 | 12 weeks | |

| Yamaguchi et al. (28) | 2007 | RS | 16 117 | 7260 | 8812 | NR | 9 days |

| Lapi et al. (22) | 2010 | RS | 502 | NR | NR | 61 | NR |

| Torre-Cisneros et al. (25) | 2015 | RCT | 33 | 30 | 3 | 56.5 | 9 months |

| Baik et al. (30) | 2020 | RS | 328 654 | 130 739 | 197 915 | NR | NR |

| Kim et al. (21) | 2021 | RS | 6229 | 3347 | 2882 | 13.87 | 8.5 days |

CC, case–control; NR, not reported; PS, prospective study; RS, retrospective study; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

The mean age was described in seven studies, being 53.0 ± 15.6 years in the adult population (431 730 patients), and 3.3 ± 3.7 years in the two studies (14, 21) focused on the childhood population (7569 patients). Six studies reported patient gender, for a total of 142 764 male (40.3%) and 211 405 female (59.7%) patients. Median fluoroquinolone treatment duration was reported by six studies and accounted for 9.5 days (range: 8.5 days–9 months). Ciprofloxacin was the most prescribed molecule and was administered in eight studies to 242 957 patients (55.3%), levofloxacin was administered in eight studies to 176 545 patients (40.2%), ofloxacin was administered in five studies to 1941 patients (0.4%), and other fluoroquinolone molecules were administered in six studies to 17 856 patients (4.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Achilles tendon complications stratified for fluoroquinolone molecule type.

| Study | Treatment | AT/ATR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levo | Cipro | Oflo | Other | Levo | Cipro | Oflo | Other | |

| van der Linden et al. (27) | NR | 456 | 418 | 1030 | NR | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Chhajed et al. (20) | NR | 72 | NR | NR | NR | 20 | NR | NR |

| van der Linden et al. (29) | NR | 4538 | 1088 | 776 | NR | 29 | 13 | 4 |

| van der Linden et al. (26) | NR | 46 | 10 | 10 | NR | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| Seeger et al. (23) | 204 | 492 | 74 | 67 | 7 | 34 | 5 | 6 |

| Noel et al. (14) | 1340 | NR | NR | NR | 2 | NR | NR | NR |

| Senneville et al. (24) | 84 | NR | NR | NR | 3 | NR | NR | NR |

| Yamaguchi et al. (28) | 16 117 | NR | NR | NR | 8 | NR | NR | NR |

| Lapi et al. (22) | 231 | 110 | NR | 161 | 24 | 5 | NR | 3 |

| Torre-Cisneros et al. (25) | 33 | NR | NR | NR | 1 | NR | NR | NR |

| Baik et al. (30) | 234 994 | 155 991 | NR | 14 728 | 277 | 376 | NR | 44 |

| Kim et al. (21) | 2545 | 2249 | 351 | 1084 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 176 545 | 242 957 | 1,941 | 17 856 | 326 | 479 | 26 | 60 |

AT, Achilles tendinopathy; ATR, Achilles tendon rupture; Cipro, ciprofloxacin; Levo, levofloxacin; NR, not reported; Oflo, ofloxacin.

Seven studies reported the reasons for fluoroquinolone treatment (14, 20, 21, 24, 25, 27, 28): the pathologies most commonly treated were respiratory infections, followed by urinary tract infections, bone infections, otitis media, gastrointestinal infections, and other infections. In one study, levofloxacin was administered as prophylaxis for tuberculosis in liver-transplanted patients (25). Other comorbidities frequently reported across the studies were diabetes, obesity, renal failure, immunodeficiency, neuromuscular diseases, organ transplantation, and a history of allergies.

Information about the dosage was heterogeneous across the studies: levofloxacin was administered usually at a dose of 500 mg/day, albeit the study by Senneville et al. (24) addressed the safety of a prolonged high-dose levofloxacin therapy, ranging from 750 to 1000 mg/day. The other molecule dosages were expressed as defined daily dose (DDD), DDD equivalent, DDD/1000/day, cumulative dose, or total dose. Furthermore, the post-marketing surveillance studies did not report, because of their design, the amount of drugs taken by the single patient. Concomitant fluoroquinolones and corticosteroid intake was reported in many of the included studies, but only four documented these data stratified for molecule type (200/2787 patients, 7.17%) (20, 23, 27, 28). In one study, patients were simultaneously treated with levofloxacin and another antibiotic for 4 weeks (24), while other studies reported the concomitant intake of other drugs without further descriptions (14, 22, 28). All transplanted patients received, as per clinical practice, multiple immunosuppressive therapy at the same time as fluoroquinolone intake (20, 25).

AT and ATR occurred in 891 patients: 326/176 545 patients treated with levofloxacin, 479/242 957 treated with ciprofloxacin, 26/1941 with ofloxacin, and 60/17 856 treated with other molecules (Table 2). Only four studies reported the gender of patients who suffered Achilles tendon complications: 21 men and 11 women. The mean interval between fluoroquinolone intake and the development of symptoms was reported in three studies (14, 25, 29) and accounted for 11 ± 5 days. Most of the included studies considered AT and ATR as possibly secondary to the fluoroquinolone intake if these complications occurred within 1 month after the last fluoroquinolone consumption (21, 27). Nevertheless, other authors considered the association of Achilles tendon lesions and fluoroquinolone consumption over a wider period of time (14, 22).

Seven of the included studies analyzed AT and ATR incidence in control groups who did not receive fluoroquinolone treatment: among 2 268 669 patients, there were 3359 AT and ATR, with an overall incidence of 0.15%. On the other hand, in the same seven studies, among 15 480 patients treated with fluoroquinolones, there were 149 AT and ATR, with an overall incidence of 0.96%. Finally, only a few studies reported AT and ATR rates separately, while the majority grouped Achilles tendon complications in the same category, thus preventing from performing a further sub-analysis.

Meta-analysis results

For the purpose of the analysis, the included studies were divided based on the patient population considered. Since only two studies reported data from a pediatric population, a meta-analysis was not feasible because of the lack of sufficient data. A meta-analysis was performed on ten studies reporting data from an adult population. In the adult population, the expected risk of AT/ATR was 0.17% (95% CI 0.15–0.19, standard error (s.e.) 0.24) for levofloxacin, 0.17% (95% CI 0.16–0.19, s.e. 0.20) for ciprofloxacin, 1.40% (95% CI 0.88–s.e.2.03, S.E. 2.51) for ofloxacin, and 0.31% (95% CI 0.23–0.40, SE 0.77) for the other molecules (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot on the relative risk of Achilles tendon damage stratified for each molecule.

The comparison between groups documented a significantly higher AT/ATR rate in the ofloxacin group (P < 0.0001 for each comparison). Levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin showed an inferior risk compared to other molecules (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.004, respectively). No statistically significant differences were detected between levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin (P = n.s.). The results of the one-to-one comparison are reported in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison between groups.

Risk of bias

According to Downs and Black’s ‘Checklist for Measuring Quality’, the included studies showed an overall good quality, with 0 studies classified as poor, two as fair, ten as good, and none as excellent (Fig. 4). Mostly, the factors reducing quality were attributable to the design of the included studies and the low statistical power of some papers.

Figure 4.

Downs and Black’s risk of bias of the included articles (14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30).

Discussion

The main finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis is that, among the fluoroquinolone molecules analyzed, ofloxacin demonstrated a significantly higher rate of AT and ATR complications, while levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin showed a safer profile compared to all the other molecules.

Fluoroquinolones are one of the most prescribed antibiotic categories, but their use implies the risk of many adverse reactions (31), including significant myocardial and musculoskeletal complications (32, 33). The development of pharmacological research has resulted in new products available on the market, and nowadays the term fluoroquinolones represents a broad category that includes more than a dozen different molecules. Nonetheless, over the years, many fluoroquinolone molecules were retired and withdrawn from the market due to serious side effects (34). In addition, the worldwide issue of bacterial resistance forces a drastic limitation in antibiotic prescriptions (35, 36), in order to avoid unnecessary consumption (37, 38). However, fluoroquinolones remain essential medications to target a wide variety of bacteria, especially those responsible for respiratory tract infections (e.g. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycoplasma pneumonia (39)) and gastrointestinal infections (e.g. Campylobacter jejuni (37)). Fluoroquinolones’ antibacterial effects are explicated by targeting bacteria DNA gyrase and other topoisomerase (40), thus representing an efficient first-line treatment for many infections. In addition, fluoroquinolones are essential when dealing with bacteria resistance to other antibiotics such as tetracycline or macrolides (39). Accordingly, in the studies that were included in this review, the pathologies most frequently treated with fluoroquinolones were respiratory tract infections, and ciprofloxacin was the most prescribed molecule.

With regard to the musculoskeletal side effects, the association of fluoroquinolone intake and tendinitis, tendon ruptures, arthralgia, and myalgia has been widely documented in the literature (41, 42, 43, 44), leading to an increased cautious approach in fluoroquinolone prescription by clinicians over the past decades (7). In 2008, the FDA added a ‘black box’ warning label to fluoroquinolones, highlighting the risk of tendon damage and encouraging the prescription of other antibiotics (45). This warning was strengthened on two occasions by the EMA (11) and the FDA itself. Thus, special attention is required when prescribing all types of fluoroquinolones.

The published literature identified by this systematic research confirms the interest of the scientific community in fluoroquinolone risk–benefit assessment, as many of the included studies analyzed the safety profile of fluoroquinolones through post-marketing surveillance based on national databases, spontaneous reports of adverse drug reactions, and insurance claims. The randomized controlled trial by Torre-Cisneros et al. (25) was even suspended by the safety committee due to an unexpected high incidence of tenosynovitis in liver-transplanted patients allocated to the levofloxacin arm. A possible explanation for such a high complication rate may be the concomitant intake of steroids and immunosuppressive therapy in the study population. Nonetheless, while the vast majority of the available literature agrees on the cumulative effect of fluoroquinolones and steroids in the development of tendon injuries (12, 46), other studies report only a low to moderate association (47, 48), and more studies are needed to clarify the extent of this negative drug interaction toward an increased complication risk.

The majority of AT and ATR are secondary to traumatic and/or degenerative events unrelated to the intake of these drugs. Nonetheless, the increased risk of AT and ATR associated with fluoroquinolones is an important topic that must be considered in the patient’s anamnestic history, potentially discovering a higher-than-expected role of pharmacologically induced tendon alterations, and possibly adding more information to be considered for the therapeutic choice in terms of antibiotic indication. The importance of this topic is supported by previous studies that already addressed fluoroquinolones’ effects on Achilles tendons (1). However, only a few studies in the literature investigated the risk of tendon injuries stratifying it for each molecule of fluoroquinolones, obtaining contrasting results: van der Vlist et al. and Stephenson et al. stated that ofloxacin carries the highest risk of tendon damage (7, 49), while Shu et al. found the highest rates of AT and ATR in patients prescribed with ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, respectively (41). Bidell et al. documented an increased risk with levofloxacin (46) as well, but this result is in contrast with the findings of Liu et al., which documented a relatively safe profile of levofloxacin (50). To shed some light on this controversial aspect, this meta-analysis addressed this topic in-depth, underlining the highest risks of ofloxacin in causing AT and ATR side effects, while levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin showed an inferior risk compared to all the other molecules.

While a different risk was documented, all molecules still carry a significant risk of complications. It remains fundamental for clinicians to be aware of the possible complications of all fluoroquinolones and to limit their use while encouraging the use of alternative drugs when possible. On the other hand, when the prescription of fluoroquinolones is needed, it is important to lower the risk of side effects like Achilles tendon injuries, which account for one of the most frequent complications with possible long-lasting effects that significantly affect the patient’s quality of life (51). The literature suggests that independent risk factors for AT and ATR during fluoroquinolone treatment are patient’s age over 60 years, renal failure, organ transplantation, immunodeficiency, and the association with concomitant corticosteroid use (12, 46). When these comorbidities are present, the prescription of another class of antibiotics should be strongly considered. Unfortunately, due to the lack of sufficient data stratified for molecule type, it was not possible to investigate the correlation of AT and ATR with patients’ comorbidities and concomitant treatments, an important aspect that should be addressed by future studies.

This study also presents other limitations reflecting the limitations of the available literature. First, despite the large number of studies reporting the prevalence of AT and ATR during fluoroquinolone treatment, only a few of them stratified the risk for each type of molecule, thus reducing the number of studies available for analysis. In addition, sufficient stratified data were available only for the most frequently prescribed molecules (levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin), impairing further analysis. The same issue was encountered for AT and ATR subanalyses, which were not feasible since many studies reported only broadly Achilles tendon complications without further dividing between tendinitis/tendinopathy and tendon rupture. Lastly, some of the included studies described adverse drug reactions of fluoroquinolones based on spontaneous pharmacovigilance reports on outpatient prescriptions and use of fluoroquinolones, thus weakening both the diagnostic reliability of Achilles tendon damage and a methodologically correct analysis of the cause–effect relationship with tendon damage. In order to strengthen the evidence on fluoroquinolones’ side effects, pharmacovigilance data should be integrated with more structured epidemiological studies. However, this last aspect did not affect the primary objective of the study, which was the assessment of the relative risk of AT and ATR stratified for each fluoroquinolone molecule. Based on the systematic review of the available data, this meta-analysis proved that ofloxacin showed the greatest risk of causing Achilles tendon complications, while levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin demonstrated statistically significant safer profiles compared to all the other molecules analyzed.

Conclusion

Among the fluoroquinolone molecules analyzed, ofloxacin demonstrated a significantly higher rate of AT and ATR complications in the adult population, while levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin showed a safer profile compared to all the other molecules. While the included studies showed an overall good quality, more data are needed to identify other patient and treatment-related factors influencing the risk of musculoskeletal complications.

ICMJE Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the study reported.

Funding Statement

This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

References

- 1.Tsai WC & Yang YM. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy. Chang Gung Medical Journal 201134461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asplund CA & Best TM. Achilles tendon disorders. BMJ 2013346f1262. ( 10.1136/bmj.f1262) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimatsu K Subramaniam S Sim H & Aronowitz P. Ciprofloxacin-induced tendinopathy of the gluteal tendons. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2014291559–1562. ( 10.1007/s11606-014-2960-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muzi F Gravante G Tati E & Tati G. Fluoroquinolones-induced tendinitis and tendon rupture in kidney transplant recipients: 2 cases and a review of the literature. Transplantation Proceedings 2007391673–1675. ( 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.01.077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godoy-Santos AL Bruschini H Cury J Srougi M de Cesar-Netto C Fonseca LF & Maffulli N. Fluoroquinolones and the risk of Achilles tendon disorders: update on a neglected complication. Urology 201811320–25. ( 10.1016/j.urology.2017.10.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pouzaud F Dutot M Martin C Debray M Warnet JM & Rat P. Age-dependent effects on redox status, oxidative stress, mitochondrial activity and toxicity induced by fluoroquinolones on primary cultures of rabbit tendon cells. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Toxicology and Pharmacology 2006143232–241. ( 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson AL Wu W Cortes D & Rochon PA. Tendon injury and fluoroquinolone use: a systematic review. Drug Safety 201336709–721. ( 10.1007/s40264-013-0089-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huruba M Farcas A Leucuta DC Sipos M & Mogosan C. Survey of healthcare professionals to assess the awareness, knowledge and self-reported behavior regarding recent fluoroquinolones safety issues. Medicine and Pharmacy Reports 202194498–506. ( 10.15386/mpr-1979) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA news release. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: (https://wwwfdagov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm612995htm) [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers. Available at: (http://waybackarchive-itorg/7993/20170112032310/http://wwwfdagov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm126085htm) [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Medicines Agency. Disabling and Potentially Permanent Side Effects Lead to Suspension or Restrictions of Quinolone and Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics. Available at: (https://wwwemaeuropaeu/en/medicines/human/referrals/quinolone-fluoroquinolone-containing-medicinal-products) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alves C Mendes D & Marques FB. Fluoroquinolones and the risk of tendon injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2019751431–1443. ( 10.1007/s00228-019-02713-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones RN Low DE & Pfaller MA. Epidemiologic trends in nosocomial and community-acquired infections due to antibiotic-resistant gram-positive bacteria: the role of streptogramins and other newer compounds. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 199933101–112. ( 10.1016/s0732-8893(9800108-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noel GJ Bradley JS Kauffman RE Duffy CM Gerbino PG Arguedas A Bagchi P Balis DA & Blumer JL. Comparative safety profile of levofloxacin in 2523 children with a focus on four specific musculoskeletal disorders. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 200726879–891. ( 10.1097/INF.0b013e3180cbd382) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drago L Nicola L Rodighiero V Larosa M Mattina R & De Vecchi E. Comparative evaluation of synergy of combinations of beta-lactams with fluoroquinolones or a macrolide in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 201166845–849. ( 10.1093/jac/dkr016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, and the PRISMA-DTA Group, Clifford T, Cohen JF, Deeks JJ, Gatsonis C, et al.Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA 2018319388–396. ( 10.1001/jama.2017.19163) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. & PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery 20108336–341. ( 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downs SH & Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 199852377–384. ( 10.1136/jech.52.6.377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman MF & Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Annals of Mathematical Statistics 195021607–611. ( 10.1214/aoms/1177729756) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chhajed PN Plit ML Hopkins PM Malouf MA & Glanville AR. Achilles tendon disease in lung transplant recipients: association with ciprofloxacin. European Respiratory Journal 200219469–471. ( 10.1183/09031936.02.00257202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y Park GW Kim S Moon HJ Won S Chung W & Yang HJ. Fluoroquinolone and no risk of Achilles-tendinopathy in childhood pneumonia under eight years of age-a nationwide retrospective cohort. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2021133399–3408. ( 10.21037/jtd-20-2256) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapi F, Tuccori M, Motola D, Pugi A, Vietri M, Montanaro N, Vaccheri A, Leoni O, Cocci A, Leone R, et al. Safety profile of the fluoroquinolones: analysis of adverse drug reactions in relation to prescription data using four regional pharmacovigilance databases in Italy. Drug Safety 201033789–799. ( 10.2165/11536810-000000000-00000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeger JD West WA Fife D Noel GJ Johnson LN & Walker AM. Achilles tendon rupture and its association with fluoroquinolone antibiotics and other potential risk factors in a managed care population. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 200615784–792. ( 10.1002/pds.1214) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senneville E, Poissy J, Legout L, Dehecq C, Loïez C, Valette M, Beltrand E, Caillaux M, Mouton Y, Migaud H, et al. Safety of prolonged high-dose levofloxacin therapy for bone infections. Journal of Chemotherapy 200719688–693. ( 10.1179/joc.2007.19.6.688) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torre-Cisneros J, San-Juan R, Rosso-Fernández CM, Silva JT, Muñoz-Sanz A, Muñoz P, Miguez E, Martín-Dávila P, López-Ruz MA, Vidal E, et al. Tuberculosis prophylaxis with levofloxacin in liver transplant patients is associated with a high incidence of tenosynovitis: safety analysis of a multicenter randomized trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2015601642–1649. ( 10.1093/cid/civ156) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Linden PD Sturkenboom MCJM Herings RMC Leufkens HMG Rowlands S & Stricker BHC. Increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture with quinolone antibacterial use, especially in elderly patients taking oral corticosteroids. Archives of Internal Medicine 20031631801–1807. ( 10.1001/archinte.163.15.1801) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Linden PD van de Lei J Nab HW Knol A & Stricker BH. Achilles tendinitis associated with fluoroquinolones. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 199948433–437. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00016.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaguchi H Kawai H Matsumoto T Yokoyama H Nakayasu T Komiya M & Shimada J. Post-marketing surveillance of the safety of levofloxacin in Japan. Chemotherapy 20075385–103. ( 10.1159/000099032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Linden PD Sturkenboom MC Herings RM Leufkens HG & Stricker BH. Fluoroquinolones and risk of Achilles tendon disorders: case-control study. BMJ 20023241306–1307. ( 10.1136/bmj.324.7349.1306) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baik S Lau J Huser V & McDonald CJ. Association between tendon ruptures and use of fluoroquinolone, and other oral antibiotics: a 10-year retrospective study of 1 million US senior Medicare beneficiaries. BMJ Open 202010e034844. ( 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034844) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owens RC Jr & Ambrose PG. Clinical use of the fluoroquinolones. Medical Clinics of North America 2000841447–1469. ( 10.1016/s0025-7125(0570297-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postma DF Spitoni C van Werkhoven CH van Elden LJR Oosterheert JJ & Bonten MJM. Cardiac events after macrolides or fluoroquinolones in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia: post-hoc analysis of a cluster-randomized trial. BMC Infectious Diseases 20191917. ( 10.1186/s12879-018-3630-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taubel J Pimenta D Cole ST Graff C Kanters JK & Camm AJ. Effect of hyperglycaemia in combination with moxifloxacin on cardiac repolarization in male and female patients with type I diabetes. Clinical Research in Cardiology 20221111147–1160. ( 10.1007/s00392-022-02037-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhanel GG Ennis K Vercaigne L Walkty A Gin AS Embil J Smith H & Hoban DJ. A critical review of the fluoroquinolones: focus on respiratory infections. Drugs 20026213–59. ( 10.2165/00003495-200262010-00002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khademi F & Sahebkar A. Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Microbiology 202020208868197. ( 10.1155/2020/8868197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abraham S Sahibzada S Hewson K Laird T Abraham R Pavic A Truswell A Lee T O’Dea M & Jordan D. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli among Australian chickens in the absence of fluoroquinolone use. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 202086. ( 10.1128/AEM.02765-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins JP King LM Collier SA Person J Gerdes ME Crim SM Bartoces M Fleming-Dutra KE Friedman CR & Francois Watkins LK. Antibiotic prescribing for acute gastroenteritis during ambulatory care visits-United states, 2006–2015. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2022431880–1889. ( 10.1017/ice.2021.522) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fluoroquinolone safety labeling changes. US Food and Drug Administration website. Available at: (https://wwwfdagov/media/104060/download) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn JG, Cho HK, Li D, Choi M, Lee J, Eun BW, Jo DS, Park SE, Choi EH, Yang HJ, et al. Efficacy of tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones for the treatment of macrolide-refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases 2021211003. ( 10.1186/s12879-021-06508-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spencer AC & Panda SS. DNA gyrase as a target for quinolones. Biomedicines 202311. ( 10.3390/biomedicines11020371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shu Y Zhang Q He X Liu Y Wu P & Chen L. Fluoroquinolone-associated suspected tendonitis and tendon rupture: a pharmacovigilance analysis from 2016 to 2021 based on the FAERS database. Frontiers in Pharmacology 202213990241. ( 10.3389/fphar.2022.990241) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang CK, Chien WC, Hsu WF, Chiao HY, Chung CH, Tzeng YS, Huang SW, Ou KL, Wang CC, Chen SJ, et al.Positive association between fluoroquinolone exposure and tendon disorders: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Frontiers in Pharmacology 202213814333. ( 10.3389/fphar.2022.814333) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huruba M Farcas A Leucuta DC Bucsa C Sipos M & Mogosan C. A VigiBase descriptive study of fluoroquinolone induced disabling and potentially permanent musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders. Scientific Reports 20211114375. ( 10.1038/s41598-021-93763-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu X Jiang DS Wang J Wang R Chen T Wang K Cao S & Wei X. Fluoroquinolone use and the risk of collagen-associated adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Safety 2019421025–1033. ( 10.1007/s40264-019-00828-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanne JH. FDA adds “black box” warning label to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. BMJ 2008337a816. ( 10.1136/bmj.a816) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bidell MR & Lodise TP. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: does levofloxacin pose the greatest risk? Pharmacotherapy 201636679–693. ( 10.1002/phar.1761) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claessen FMAP de Vos RJ Reijman M & Meuffels DE. Predictors of primary Achilles tendon ruptures. Sports Medicine 2014441241–1259. ( 10.1007/s40279-014-0200-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.516 Xergia SA Tsarbou C Liveris NI Hadjithoma Μ & Tzanetakou IP. Risk factors for Achilles tendon rupture: an updated systematic review. Physician and Sportsmedicine 202351506–. ( 10.1080/00913847.2022.2085505). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Vlist AC Breda SJ Oei EHG Verhaar JAN & de Vos RJ. Clinical risk factors for Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019531352–1361. ( 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099991) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu HH. Safety profile of the fluoroquinolones: focus on levofloxacin. Drug Safety 201033353–369. ( 10.2165/11536360-000000000-00000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sode J Obel N Hallas J & Lassen A. Use of fluoroquinolone and risk of Achilles tendon rupture: a population-based cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 200763499–503. ( 10.1007/s00228-007-0265-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a