Abstract

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) report high rates of sleep problems. In 2012, the Autism Treatment Network/ Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health (ATN/AIR-P) Sleep Committee developed a pathway to address these concerns. Since its publication, ATN/AIR-P clinicians and parents have identified night wakings as a refractory problem unaddressed by the pathway. We reviewed the existing literature and identified 76 scholarly articles that provided data on night waking in children with ASD. Based on the available literature, we propose an updated practice pathway to identify and treat night wakings in children with ASD.

Keywords: Sleep problems, Autism spectrum disorder, Night wakings, Treatment for insomnia, Sleep initiation, Sleep maintenance

Introduction

Approximately 1 in 44 children have autism spectrum disorder (ASD), defined by diagnostic criteria that include deficits in social communication and social interaction, and restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (Maenner et al., 2021). Sleep problems commonly co-occur in this population; indeed, sleep problems are estimated to be more than twice as common in young children ages 2–5 years with ASD than in the general population (Reynolds et al., 2019), and they often persist into adolescence (Goldman et al., 2012). Approximately 50–80% of parents of children with ASD report sleep problems in their child (Couturier et al., 2005; Goldman et al., 2012; Krakowiak et al., 2008), including various types of insomnia, such as difficulty falling asleep, bedtime resistance, prolonged night wakings, and short sleep duration (Richdale & Schrek, 2009; Williams et al., 2004).

Sleep problems in children with ASD are associated with hyperactive/impulsive behavior, disruptive behavior and other daytime behavior problems. Night wakings in particular show associations with physical aggression, irritability, and hyperactivity (Mazurek & Sohl, 2016). Night wakings and sleep onset delay contribute to short sleep duration, which is associated with poorer adaptive functioning in daily living skills, social skills, motor development; and restricted and repetitive behaviors (Taylor et al., 2012; Veatch et al., 2017). Health-related quality of life is also affected in children with ASD and short sleep duration (Delahaye et al., 2014). Furthermore, bidirectional relationships of disordered sleep with immune dysregulation make children at greater risk for other physical and neuropsychiatric problems (Iranzo, 2020; Louveau et al., 2015; Winkelman & Lecea, 2020; Yin et al., 2021; Zielinski & Gibbons, 2022). Beyond the child’s own health, consistent sleep problems contribute to maternal stress and poorer maternal mental health (Hodge et al., 2013). Fortunately, treatment of sleep problems in children with ASD, using behavioral or pharmacologic approaches, results in improvements in child behavior and family functioning (Malow et al., 2012, 2014).

To address the multifaceted problem of sleep disturbance and related impairments, the joint Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network and Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health (ATN/AIR-P) published a practice pathway for the identification, evaluation, and management of insomnia in children with ASD (Malow et al., 2012). This practice pathway was based on expert consensus with the goal of capturing best practices for an overarching approach to insomnia by a general pediatrician, primary care provider, or autism medical specialist, and included a systematic literature review and grading of evidence. Key points of the practice pathway included (a) screening the child for insomnia using a few targeted questions related to key sleep concerns (e.g., sleep onset delay, co-sleeping, sleep duration, night wakings); (b) identifying and managing medical contributors that can affect sleep (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux, epileptic seizures, atopic disease such as asthma and eczema), (c) providing educational/behavioral interventions, and (d) close follow-up, with institution of medications or referral to a sleep specialist for persistent sleep problems. The practice pathway was designed to be broad and cover a variety of sleep problems.

Network providers and parents noted that the 2012 pathway mainly addressed difficulties with sleep onset. The separate issue of night wakings remains challenging and continues to have clinical significance. Even after controlling for the effects of age and sex, night wakings have shown a strong association with daytime behavioral problems (Mazurek & Sohl, 2016). The prevalence of occasional or frequent night wakings in an ATN-related sample was approximately 50% (Katz et al, 2018). There are several reasons for emphasizing night wakings. Night wakings may be reflective of specific medical problems, such as obstructive sleep apnea, which wakes children from sleep to promote a resumption of breathing, poorly controlled asthma or atopic disease, all of which can result in sleep disruption. Indeed, a wide range of major medical conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), constipation, restless leg syndrome, or seizures can be associated with night wakings. Finally, although educational/behavioral approaches and pharmacologic intervention are often effective in addressing sleep onset delay, bedtime resistance, and co-sleeping (when reported as problematic by the parent or caregiver), in our clinical experience the sleep concern of night wakings is often refractory to treatment with educational/behavioral approaches and/or pharmacologic intervention. Therefore, the ATN/AIR-P Sleep Committee reconvened to update the 2012 practice pathway for insomnia, with an emphasis on night wakings. In this review, the committee examined the definition of night wakings including number, duration and impacts on children, families and caregivers. The committee recognized that a working definition for night wakings would improve differential diagnosis and evaluation of clinical interventions.

Methods

Systematic Review of the Literature

A systematic literature review was conducted to find evidence regarding the treatment of insomnia in children diagnosed with ASD (questions and search terms available on request from the authors). Consistent with the International Classification of Sleep Disorders 3rd edition (2014) diagnostic criteria for insomnia, we included difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and waking up earlier than desired. The reviews were completed by nine physicians and one research coordinator. Each physician reviewed 20–25 research abstracts, five of which were double reviewed by a second reviewer. Reviewers indicated whether an article was “definitely relevant,” “possibly relevant,” or “not relevant” to the issue of insomnia in children with ASD. Articles considered definitely relevant were advanced for full text review (review form is included as an end note). Those considered “ not relevant” by all reviewers were excluded from further consideration. The remaining articles (i.e., those with “possibly relevant” or conflicting characterizations) were reviewed by AG and JF.

Search engines included PubMed, OVID, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EBM Database of Abstracts and Reviews of Effects, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews. The search was limited to studies with human subjects conducted between 1/1/1990 and 10/15/2018. For the most comprehensive evaluation of the literature on the treatment of night wakings, studies published prior to the 2012 practice pathway were included if data were not presented in that prior pathway. This initial search yielded 981 manuscripts. Other systematic literature reviews found in this initial search were reviewed for primary manuscripts not captured in the search. This resulted in an additional 13 manuscripts. After removing the systematic reviews and any duplicate manuscripts, 583 unique abstracts remained. These were each reviewed by two ATN/AIR-P Sleep Committee members. Reviewers identified 212 manuscripts for full text review, with 76 articles providing data on night wakings. Due to the paucity of data on night wakings, we did not set specific exclusion criteria based on sample size.

The 76 resultant articles were each evaluated using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) for Systematic Reviews guidelines (Guyatt et al, 2011). The articles were distributed among ten authors for review. Each author presented their findings to the full ATN/AIR-P Sleep Committee in monthly meetings, and questions were resolved by committee consensus.

One of the challenges in our evaluation and understanding of night wakings was the lack of a consistent definition or reporting format. Of the 76 papers reviewed the most common tool used for reporting of night wakings was parental report, via sleep diary and/or sleep survey. A small subset of articles relied upon polysomnography or actigraphy (instead of or in addition to parent report measures). A variety of surveys were used across these studies to measure sleep disturbances, including the Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ), Simonds & Parraga Sleep Questionnaire (SPSQ), Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and other locally developed sleep questionnaires. Although not all instruments in the set of 76 articles were available for committee review, most available questionnaires included one or two items on the occurrence of night wakings.

Results

Across the 76 articles reviewed, there was no consistent definition for night wakings. Most articles (63/76) relied upon parent reported measures to assess night wakings..About one-third of the reports (27/76) included actigraphy. Polysomnography was less frequently used (10/76)., or retrospective clinical observation by chart review of parent reported sleep duration or completed sleep questionaires. Within the articles, several sleep disturbances were reported that the committee felt qualified as night wakings. These included nighttime or early morning wakings by subjective parent report, as well as decreased sleep efficiency, sleep fragmentation, and increased wake after sleep onset (WASO) as measured by polysomnography (PSG).

The 76 studies were placed into one or more of five broad categories based on the focus of the article: 1) frequency of night wakings, 2) frequency of night waking in children with ASD vs. children without ASD, 3) evaluation of tools used to identify night wakings, 4) other factors or conditions associated with night wakings, and 5) treatment/intervention for night wakings. Articles that addressed multiple domains were repeated in all relevant categories.

Frequency of Night Wakings in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

The prevalence of night wakings is difficult to accurately identify due to a lack of a consistent measure; however, our review supports the contention that night wakings are a common concern in the pediatric ASD population. The most common sleep disturbances reported, apart from increased night wakings, were increased wake after sleep onset (WASO), poor sleep quality, and decreased sleep efficiency. These were identified predominantly by polysomnography and actigraphy, though with some subjective identification of poor sleep quality on questionnaires. Most articles identified some difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep (DIMS) but did not necessarily specify the type of sleep disturbance. Of note, there were limited studies that evaluated night wakings alone; most of the articles we reviewed evaluated night wakings as part of a constellation of broader sleep disturbances.

Table 1 shows the nine papers that provided a calculated rate of night wakings in children with ASD without a comparison group. These studies indicate that the prevalence of night wakings in children with ASD ranges from 0 to 84% depending on the definition used and the method of reporting and the population studied. Based on the relatively small number of available studies, there is insufficient data to pinpoint an accurate range for the prevalence of night wakings in children with ASD. However, the study with the largest number of subjects (n = 210) reported a prevalence of 34% (Williams et al., 2004). This seems to be a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of night wakings in children with ASD given that it utilized the largest sample size, it represents the median rate reported across these studies, and it is consistent with the literature on sleep disturbances in children with Autism (Malow et al., 2016). One study that may be excluded from our evaluation is that of Oyane and Bjorvatn (2005) as it studied older teens and adults ranging from 15 to 25 years with a sample size of 15 participants with 0% night wakings.

Table 1.

Frequency of Night Wakings in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Author(s) | Age range | N | Tool used to measure sleep | Rate of Night Wakings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rossi et al., 1999 | 2–20 | 8 | Not specified | 44% |

| Tani et al., 2003 | 26.5 ± 8.1 | 20 | BNSQ; sleep diary; free description via short essay | 30% |

| Wiggs & Stores, 2004 | 5–16 | 69 | SPSQ; sleep diary; actigraphy | 33% |

| Williams et al., 2004 | 2–16 | 210 | Modified sleep survey | 34% |

| Oyane & Bjorvatn, 2005 | 15–25 | 15 | Sleep diaries; sleep questionnaire; ESS; actigraphy | 0% |

| Ming et al., 2009 | 3–15 | 23 | Sleep questionnaires; PSG | 84.6% |

| Youssef et al., 2013 | 4.8–12.8 | 53 | PSG | 42% |

| Ayyash et al., 2015 | 6.3 ± 1.7 years | 9 | Sleep diary | 31% |

| Veatch et al., 2016 | 2–10 | 80 | CSHQ; actigraphy | 72% |

BNSQ Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire, SPSQ Simonds & Parraga Sleep Questionnaire, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, PSG = Polysomnography, CSHQ Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire

Frequency of Night Wakings in Children with ASD Compared to Other Groups

Table 2 includes the 27 articles in which the prevalence of night wakings was compared between children with ASD and another group, most commonly neuro-typically developing children. Within these, 16 articles reported an increased rate of night wakings compared to other groups, nine articles found no significant difference between the ASD population and the comparison group, and two articles (Anders et al., 2011, 2012) reported lower rates of night wakings in children with ASD compared to other groups.

Table 2.

Frequency of Night Wakings in Children with ASD Compared with Other Groups

| Author(s) | Age range | Sample Size | Tool used to measure sleep | Relationship to Comparison Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diomedi et al., 1999 | 12–24 | ASD, n = 10; TD, n = 8 | PSG | |

| Hering et al., 1999 | 3–12 | ASD, n = 8; TD, n = 8 | Actigraphy | |

| Tani et al., 2003 | 26.5 ± 8.1 | ASD, n = 20; TD, n = 10 | BNSQ; sleep diary; free description via short essay | |

| Tani et al., 2004 | 20 + | ASD, n = 20; TD, n = 10 | PSG | |

| Allik et al., 2006a, 2006b | 8.5–12.8 | ASD, n = 32; TD, n = 32 | Sleep diary; actigraphy; “sleep questionnaire” | |

| Giannotti et al., 2006 | 2.6–9.6 | ASD, n = 56; TD, n = 56 | CSHQ |  |

| Hare et al., 2006 | 20–58 | ASD (+ ID), n = 14; ID, n = 17 | Care giver sleep diary | |

| Hoffman et al., 2006 | 4–16 | autism, n = 106; TD, n = 168 | CSHQ | |

| Bruni et al., 2007 | 7–15 | Asperger, n = 10; autism, n = 12; TD, n = 12 | PSG; Bruni questionnaire, PDSS, | |

| Miano et al., 2007 | 3.7–19 | 31 | Sleep questionnaire; PSG | |

| Allik et al., 2008 | 11.2–15.6 | ASD, n = 16; TD, n = 16 | Actigraphy | |

| Giannotti et al., 2008 | 2–8 | ASD, n = 104; TD, n = 162 | CSHQ; Sleep diary; 21-channel EEG |  |

| Krakowiak et al., 2008 | 3.6 years (standard deviation, 0.8 years) | ASD, n = 303; DD, n = 63; TD, n = 163 | CHARGE sleep history; CSHQ |  |

| Goldman et al., 2009 | 4–10 | ASD, n = 42; TD n = 16 | CSHQ; PCQ; actigraphy; PSG |  |

| Goodlin-Jones et al., 2008 | 2–5.5 | ASD, n = 68; DD, n = 57; TD, n = 69 | CSHQ |

DD

|

|

TD

| ||||

| Anders et al., 2011 | 2–5.5 | ASD, n = 68; DD, n = 57; TD, n = 69 | Actigraphy; sleep–wake diary |

DD

|

|

TD

| ||||

| Anders et al., 2012 | 2–5.5 | ASD, n = 69; DD, n = 57; TD = 69 | Actigraphy; CSHQ; ESS; sleep diary |

DD

|

|

TD

| ||||

| Humphreys et al., 2014 | 1.5–11 | ASD, n = 39; TD, n = 7043 | Parent questionnaires | |

| Baker & Richdale, 2015 | 21–44 | HFASD, n = 36; TD, n = 36 | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; sleep wake diary; actigraphy | |

| Lane et al., 2015 | 1–6 | ASD, n = 68; TD, n = 18;DD, n = 16 | Continuous overnight PSG, blood work |

DD

|

|

TD

| ||||

| Kheirouri et al., 2016 | 4–18 | ASD, n = 35; TD, n = 31 | CSHQ |  |

| Aathira et al., 2017 | 3–10 | ASD, n = 71; TD, n = 65 | CSHQ; PSG |  |

| Goldman et al., 2017 | 11–26 | ASD, n = 28; TD, n = 13 | ASWS; ASHS; actigraphy; melatonin level; cortisol level |  |

| Benson et al., 2019 | 18–35 | ASD, n = 15; TD, n = 17 | Actigraphy; PSQI; STOP-Bang; sleep diary | |

| Kelmanson, 2020 | 5 | ASD, n = 18; TD, n = 54 | CSHQ |  |

| Trickett et al., 2018 | 2–15 | ASD, n = 30; TD, n = 47 | SPSQ |  |

| Van der Heijden et al., 2018 | 6–12 | ASD, n = 67; ADHD, n = 44; TD, n = 243 | SDSC, parent reported sleep duration |

ADHD

|

|

TD

|

ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder, TD Typically Developing, DD Developmental Delay; ID Intellectual Disability, HFASD High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder, PSG polysomnography, BNSQ Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire, CSHQ Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, PDSS Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale, CHARGE Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment study, PCQ Parental Concerns Questionnaire, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, ASWS Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale, ASHS Adolescent Sleep-Hygiene Scale, STOP-Bang Snoring, Tiredness, Observed Apnea, Blood Pressure, Body Mass Index, Age, Neck Size, Gender; SPSQ Simonds & Parraga Sleep Questionnaire, SDSC Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children

Key:—Higher (p > 0.05), —Higher (p < 0.05),

—Higher (p < 0.05),  —no difference

—no difference ,—Lower (p > 0.05),

,—Lower (p > 0.05),  —Lower (p < 0.05)

—Lower (p < 0.05)

Evaluation of Tools Used to Identify Night Wakings

Our literature review yielded few articles that objectively evaluated a tool to identify night wakings in clinical practice. Studies comparing multiple tools to validate measurements of night wakings were also limited (Goodlin-Jones et al., 2008; Katz et al., 2018; Malow et al., 2009, 2016; Sitnick et al., 2008). Table 3 summarizes the five studies that utilized validated tools, rating scales, and diagnostic methods to evaluate night wakings. Four of the five studies used the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) as at least one of the tools to evaluate night wakings. The CSHQ (Owens et al., 2000) is a widely used 45-item validated parent report sleep screening instrument designed to assess sleep disturbance in school aged children. Only one study used actigraphy as compared to polysomnography with video and showed that actigraphy had poor agreement with polysomnography for the detection of night wakings (Sitnick et al., 2008). Three of the five articles in this table employed objective measures of night wakings (actigraphy and/or polysomnography). Notably, across all 76 studies reviewed, most studies relied on parent report or retrospective clinical observation by chart review to report night wakings. The variability in agreement across measures used to identify the occurrence of night wakings underscores the need for a standardized definition and way to identify night wakings in children with ASD.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Tools Used to Identify Night Wakings

| First Author, Year | Age range | ASD Sample Size | Tool used to measure sleep | Results related to Night wakings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goodlin-Jones et al., 2008 | 2–5 | 64 | CSHQ; actigraphy; | CSHQ-Night Wakings significantly correlated with actigraphy |

| Sitnick et al., 2008 | 2–6 | 22 | Actigraphy; video-somnography | Findings were 94% overall agreement, 97% sensitivity, and 24% specificity. Actigraphy has poor agreement for detecting nocturnal awakenings, compared to video observations |

| Malow et al., 2009 | 3–10 | 93 | FISH; CSHQ | The night wakings subscale of the Family Inventory of Sleep Habits was significantly correlated with the CSHQ for TD but not the ASD group (p = .215) |

| Reed et al., 2009 | 3–10 | 20 | CGI; CSHQ; actigraphy | Sleep CGI and CSHQ were correlated for night wakings (r = 0.40, p < .001). For each unit increase for CGI-S score, the CSHQ night wakings score increased by 0.647 units. The CGI-S did not show convergent validity with actigraphy measurements of WASO |

| Katz et al., 2018 | 4–10 | 2872 | Modified CSHQ for autism;CSHQ | The shorter, modified version of the CSHQ appears useful for identifying night wakings in children with ASD |

CSHQ Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, FISH Family Inventory of Sleep Habits, CGI Pediatric Sleep Clinical Global Impressions Scale

Other Factors or Conditions Associated with Night Wakings

Of the 76 papers reviewed, 21 discussed other factors or conditions associated with night wakings in children with ASD, as shown in Table 4. Medical or developmental co-occurring conditions were grouped into broad categories including developmental / behavioral, neurologic, psychiatric, and medical. Five studies identified night wakings associated with developmental or behavioral issues including anxiety, physical aggression, hyperactivity, hostility inattention, and autism severity (as per Gilliam Autism Rating Scale) (Abel et al, 2018; Giannotti et al., 2008; Kheirouri et al, 2016; Mazurek & Petroski, 2015; Mazurek & Sohl, 2016). Another three reports described neurologic conditions such as greater intellectual disability and developmental regression as associated with sleep disturbance (Taylor et al., 2012; Trickett et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2004). Medical pathology, as expected, was also associated with sleep disturbance. Three studies reported increased rates of night wakings in children with sleep disordered breathing, gastro-esophageal reflux or other gastrointestinal dysfunction (McCue et al, 2017; Tricket et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2004).

Table 4.

Other Factors or Conditions Associated with Night Wakings

| First Author, Year | Age range | ASD Sample Size | Tool used to measure sleep | Associated Condition(s) | Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honomichl et al., 2002 | 2–11 | 100 | CSHQ; sleep diary | Parent reported Sleep problems |  |

| Age |  |

||||

| Williams et al., 2004 | 2–16 | 210 | Modified sleep survey | Intellectual Disability | |

| Vision Problems | |||||

| Respiratory Problems | |||||

| Poor Growth | |||||

| Doo & Wing, 2006 | 2–7.6 | 193 | Chinese version of CSHQ; | Sleep Problem before age 2 |  |

| Age |  |

||||

| Giannotti et al., 2008 | 2–8 | 104 | CSHQ; Sleep diary; 21-channel EEG | Regressed ASD |  |

| Anders et al., 2012 | 2–5.5 | 69 | Actigraphy; CSHQ; ESS; sleep diary | PEP-R Perception | |

| Eye–Hand Coordination scores |  |

||||

| PEP-R Fine Motor Coordination | |||||

| Goldman et al., 2012 | 3–18 | 1859 | CSHQ; PCQ | Age |  |

| Taylor et al., 2012 | 1–18 | 335 | BEDS | Communication Problems |  |

| Richdale et al., 2014 | 15.5 (1.3) | 27 | Sleep Diary; SAAQ | SAA-Somatic |  |

| Lane et al., 2015 | 1–6 | 68 | Continuous overnight PSG, blood work | Serum ferritin levels | |

| Mazurek & Petroski, 2015 | 2–18 | 1347 | CSHQ | Age |  |

| Anxiety | |||||

| Sensory over responsivity | |||||

| Kheirouri et al., 2016 | 4–18 | 35 | CSHQ | Autism Severity | |

| Malow et al., 2016 | 4–10 | 1516 | CSHQ; medications taken | Use of sleep medication |  |

| Mazurek & Sohl, 2016 | 3.6–19.6 | 81 | CSHQ | Physical aggression |  |

| Hostility |  |

||||

| Inattention |  |

||||

| Hyperactivity |  |

||||

| Veatch et al., 2017 | 2–10 | 80 | CSHQ; actigraphy | Sleep onset delay |  |

| Age post treatment |  |

||||

| McCue et al., 2017 | 2–18 | 610 | Medical history data- sleep problems and GI problems | GI problems |  |

| Baker et al., 2017 | 25 + | 28 | Actigraphy; sleep diary; saliva collection, melatonin | Night time melatonin concentration | |

| Abel et al., 2018 | 2–10 | 42 | Actigraphy | Negative affect |  |

| Repetitive behaviors | |||||

| CBC | |||||

| Benson et al., 2019 | 18–35 | 15 | Actigraphy; PSQI; STOP-Bang; sleep diary | Next day physical activity |  |

| Kelmanson, 2020 | 5 | 18 | CSHQ | Affective problems | |

| Trickett et al., 2018 | 2–15 | 30 | SPSQ | Sleep Medication Use |  |

| Language ability | |||||

| GE reflux |  |

||||

| Van der Heijden et al., 2018 | 6–12 | 67 | SDSC, parent reported sleep duration | Sleep hygiene |

CSHQ Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, PCQ Parental Concerns Questionnaire, BEDS Behavioral Evaluation of Disorders of Sleep, SAAQ Sleep Anticipatory Anxiety Questionnaire, PSG Polysomnography, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, STOP-Bang Snoring, Tiredness, Observed Apnea, Blood Pressure, Body Mass Index, Age, Neck Size, Gender, SPSQ Simonds & Parraga Sleep Questionnaire, SDSC Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children, PEP-R Psychoeducational Profile Revised

Key: —Positive (p > 0.05),

—Positive (p > 0.05),  —Positive (p < 0.05),

—Positive (p < 0.05),  Negative (p > 0.05),

Negative (p > 0.05), Negative (p < 0.05),

Negative (p < 0.05),  -none

-none

Other factors were also reported to be associated with night wakings. Five studies identified an association between child age and night wakings (Doo & Wing, 2006; Goldman et al., 2012; Honomichl et al., 2002; Mazurek & Petroski, 2015; Veatch et al., 2017), with younger children exhibiting more night wakings than older children. One article reported an association between night wakings and next day decreased physical activity (Benson et al., 2019); another reported an association between poor sleep hygiene and increased night wakings (van der Heijden et al., 2018). Examples of poor sleep hygiene included inconsistent sleep and wake times, excessive screen time, screen time in the hours prior to bedtime, and behavioral habits such as drinking a bottle or being rocked to sleep. Ferritin levels were not correlated with wake after sleep onset (Lane et al., 2015). Anders et al (2012) observed an association between sleep disturbance and decreased scores on motor coordination tests.

Treatment and Intervention for Night Wakings

Twenty-six of the studies selected addressed treatment of night wakings in individuals diagnosed with ASD, as summarized in Table 5. The majority of these studies (25/26) focused exclusively on a pediatric population (25/26) with only one study including adults between 19 and 52. The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 2 to 185. Several types of treatment or intervention were used in these studies including medications, parental education, and behavioral interventions. Of the 26 manuscripts assessing treatment options, few were randomized controlled (9/26) studies with the majority using observational methodology (17/26). Of the 26 articles, 23 had evidence graded as Low or Very Low based on the GRADE methodology, three had Moderate evidence, and no articles had evidence rated High.

Table 5.

Treatment and Intervention for Night Wakings

| First Author, Year | Study Type | Age (range or M, SD) | ASD Sample Size | Measure of Night Wakings | Treatment | Effect on Night Wakings | GRADE85 Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paavonen et al., 2003 | Observational | 6–17 | 15 | Actigraphy, Parent Reported: CSRF; SDSC | Melatonin |  |

Very Low |

| Christodulu & Durand, 2004 | Observational | 2–6 | 2 | Parent Reported: Albany Sleep problems Scale, Parental Sleep Satisfaction Questionnaire | Positive bedtime routines and sleep restriction | Very Low | |

| Garstang & Wallis, 2009 | Randomized Controlled Trial | 4–16 | 6 | Parent Reported: Sleep Diary | 5 mg Melatonin; sleep pamphlet | Low | |

| Giannotti et al., 2006 | Observational | 2.6–9.6 | 56 | Parent Reported: CSHQ | Controlled-Release Melatonin |  |

Very Low |

| Ming et al., 2008 | Observational | 4–16 | 19 | Parent Reported: Sleep diary | Clonidine | Very Low | |

| Wasdell et al., 2008 | Randomized controlled trial | 2.05–17.81 | 16 | Actigraphy | Controlled-Release Melatonin |  |

Low |

| Galli-Carminati et al., 2009 | Observational | 19–52 | 6 | Clinical Observation | Melatonin 3 mg/d– > 6 mg/d– > 9 mg/d | Very Low | |

| Wirojanan et al., 2009 | Randomized controlled trial | 3–15 | 8 | Actigraphy | Immediate-release Melatonin |  |

Low |

| Buckley et al., 2011 | Observational | 2.5–6.9 | 5 | Polysomnography | Donepezil |  |

Very Low |

| Wright et al., 2011 | Randomized Controlled Trial | 3–16 | 16 | Parent Reported: Sleep Diary | Melatonin |  |

Low |

| Adkins et al., 2012 | Observational | 2–10 | 36 | Actigraphy | Sleep Pamphlet |  |

Low |

| Cortesi et al., 2012 | Randomized Controlled Trial | 4–10 | 185 | Actigraphy, Parent reported | 1.Controlled-release melatonin |  |

Moderate |

| 2. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |  |

||||||

| Combination 1 and 2 |  |

||||||

| Malow et al., 2012 | Observational | 3–9 | 24 | Actigraphy, Parent Reported | Melatonin |  |

Very Low |

| Johnson et al., 2013 | Randomized Controlled Trial | 2–6 | 40 | Actigraphy | Parent education |  |

Low |

| Goldman et al., 2014 | Observational | 3–10 | 9 | Actigraphy, Parent reported | Parent education, Melatonin | Very Low | |

| Knight & Johnson, 2014 | Observational | 4–5 | 3 | Parent reported | Behavioral treatment package (circadian rhythm management, positive bedtime routines, white noise, graduated extinction) | Very Low | |

| Ayyash et al., 2015 | Observational | 6.3, 1.7 | 9 | Parent reported | Immediate-release Melatonin (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg) |  |

Very Low |

| Stuttard et al., 2015 | Observational | 5–15 | 22 | Parent Reported: CSHQ | Parent education |  |

Very Low |

| Loring et al., 2016 | Observational | 11–18 | 18 | Actigraphy; Parent Reported: ASHS; ASWS; M-ESS | Parent education |  |

Very Low |

| Veatch et al., 2016 | Observational | 2–10 | 80 | Actigraphy | Parent education | Low | |

| Frazier et al., 2017 | Randomized Control Trial | 2.5–12.9 | 45 | Actigraphy, Parent Reported: sleep diary; FISH; CSHQ | Sound-To-Sleep system | Moderate | |

| Gringras et al., 2017 | Randomized Controlled Trial | 2–17.5 | 125 | Parent reported: SND | Prolonged-Release Melatonin | Low | |

| Narasingharao et al., 2017 | Observational | 5–16 | 64 | Parent reported | Yoga |  |

Very Low |

| Maras et al., 2018 | Observational | 2–17.5 | 95 | Parent reported | Prolonged- release melatonin |  |

Very Low |

| Mehrazad-Saber et al., 2018 | Randomized Controlled Trial | 4–16 | 43 | Parent reported: CSHQ | L-Carnosine |  |

Moderate |

| Delemere & Dounavi, 2018 | Observational | 2–7 | 6 | Parent Reported: CSHQ | Bedtime fading; Positive routines | Very Low |

CSRF Children’s self-report form for Sleep Disturbances, SDSC Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children, CSHQ Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire ASHS Adolescent Sleep-Hygiene Scale; ASWS Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale, M-ESS Modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FISH Family Inventory of Sleep Habits; SND Sleep and Nap Diary

Key:  —no change,

—no change,  —decrease (p>0.05),

—decrease (p>0.05),  —decrease (p<0.05)

—decrease (p<0.05)

Melatonin was the most common medication studied (13/26). Although seven studies showed that melatonin was effective in reducing night wakings (Malow et al., 2012; Galli-Carminati et al., 2009; Giannotti et al., 2006; Garstang & Wallis, 2009; Cortesi et al., 2012; Maras et al., 2018) six studies reported that it did not show significant reduction in night wakings (Ayyash et al., 2015; Gringras et al., 2017; Paavonen et al., 2003; Wasdell et al., 2008; Wirojanan et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2011). Controlled or prolonged release melatonin was evaluated in five of the 26 studies and had variable results. Some studies showed no difference whereas others showed significantly decreased night wakings. Subject groups ranged from 16 to 185 and there were a variety of study types. In the largest of these studies, a randomized controlled trial including 185 subjects (Cortesi et al., 2012), controlled-release melatonin resulted in a significant decrease in night wakings.

Other medications studied included donepezil (Buckley et al., 2011), L- carnosine (Gringras et al., 2017), and clonidine (Ming et al., 2008). The use of donepezil did not result in significant change in night wakings; however, the study had a small sample size (n = 5) and therefore these results were deemed to have Very Low strength (Buckley et al., 2011). Taking L-carnosine also did not result in significant changes in night wakings, a result with Moderate strength evidence (Mehrazad-Saber et al., 2018). Clonidine showed some decrease in night wakings; however, the significance was not assessed and the sample size was small (n = 19), resulting in Very Low strength of evidence for this finding (Ming et al., 2008).

Parent based trainings and behavioral interventions also showed mixed effectiveness across studies. Several studies showed that parent educational trainings, either provided individually or in group settings, were effective in reducing night wakings in children with ASD (Garstang & Wallis, 2009; Goldman et al., 2014; Stuttard et al., 2015; Veatch et al., 2016). Other studies found no significant change in child night wakings due to parent education (Johnson et al., 2013; Loring et al., 2016). Behavioral interventions including cognitive bedtime fading (Christodulu & Durand, 2004; Delemere & Dounavi, 2018), positive routines (Christodulu & Durand, 2004; Delemere & Dounavi, 2018; Knight & Johnson, 2014) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) when used in combination with melatonin were found to decrease night wakings (Cortesi et al., 2012). CBT when used alone did not result in any significant difference in night wakings (Cortesi et al., 2012). Yoga (Narasingharao et al., 2017) was found to significantly decrease night wakings in children with ASD but the Sound-To-Sleep mattress system (Frazier et al., 2017) did not result in a significant change in night wakings in this population.

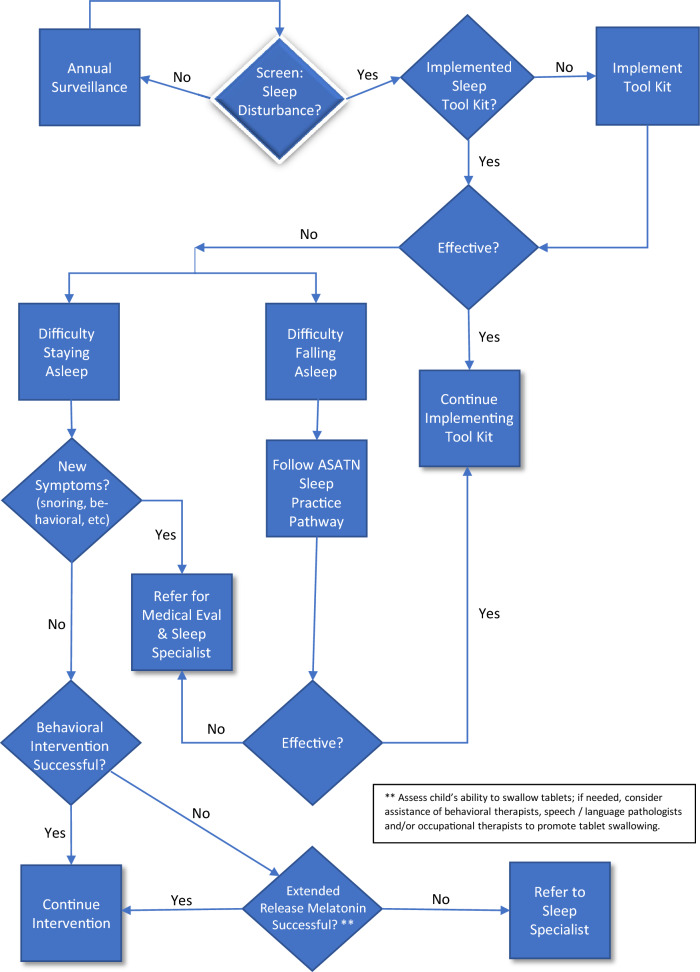

Based on the articles reviewed here, we updated the 2012 ATN Sleep Committee’s algorithm for the evaluation and treatment of insomnia in children with ASD using expert consensus within the ATN Sleep Workgroup including physicians and scientists from a variety of pediatric and adult specialties. This updated practice pathway includes the recommendations for night wakings and is the most significant update from the 2012 practice pathway. Figure 1 shows the revised practice pathway that we propose as a guide for practitioners to screen and address their patients’ sleep disturbances. It builds upon the prior pathway proposed in 2012 by the ATN / AIR-P Sleep Workgroup. As in the original pathway, the revised pathway begins with the recommendation for the parent or caregiver to implement the ATN/AIR-P Sleep Toolkit with a child exhibiting sleep disturbance. The Toolkit provides helpful strategies for daytime habits, bedtime rituals and routines, and recommendations for encouraging behaviors and habits that promote sleep. It also includes a “Quick Tips” sheet, visual aids (e.g., colorful printable posters and incentives), and videos. One primary difference between the original pathway and the proposed revised pathway is that the latter distinguishes between children who have difficulty initiating sleep vs. those who have difficulty staying asleep. The inclusion of night wakings in the revised pathway is justified by the available evidence that at least 34% of children with ASD have night wakings either alone or in combination with delayed sleep onset.”

Fig. 1.

Practice Pathway

Discussion

The vast majority of the articles for this review indicated that children with autism have more frequent or longer night wakings than their neurotypically developing peers. Given the prevalence of sleep problems in children with autism and the significant impact that lack of sleep has on child outcomes, there is alarge need for clinical guidelines to manage sleep disturbances in this population. The Sleep Committee of the ATN / AIR-P set out to update the existing practice pathway on insomnia and autism, as the original version of this practice pathway dealt primarily with sleep onset difficulties. The goal of this article is to provide more specific recommendations on night wakings, a frequent sleep problem within the broader diagnosis of insomnia, i.e., the difficulty to initiate or maintain sleep.

This systematic literature review identified 31 articles that were focused specifically on the identification or treatment of night wakings in individuals diagnosed with ASD, consisting mostly of case reports, small case series, or observational studies. There were few randomized controlled trials found in the published literature addressing night wakings in people with ASD. Due to a lack of randomized controlled trials and small sample sizes, the majority of evidence in available treatment studies was Low or Very Low (23/26) based on GRADE guidelines (Frazier et al., 2017). The paucity of data, especially those stemming from high quality research, in this area was surprising given how prevalent the problem appears.

A further limitation of the studies we reviewed was the apparent lack of a consistent definition for night wakings. A clear and consistent definition of night wakings is not currently available in the literature. The working definition of pathogenic night wakings is based on multiple sources including the ICSD-3 diagnostic criteria for insomnia, definition of an abnormal wake after sleep onset (WASO) from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events (Berry et al., 2020). It is also differentiated from physiologic arousals that occur at the end of a sleep cycle and based on available literature about the effects of night wakings on children’s sleep and daytime functioning and the effect on parents and caregivers. Based on our review of the literature, we propose a working definition of “night wakings” to be a waking of 30 min or more following sleep onset, or frequent, greater than 1 per night, shorter night wakings after sleep onset that significantly disrupt the child or their family / caregiver(s). Given the subjective data collected by parental survey and sleep diaries we are unable to clearly define the minimal time necessitated to qualify as a shorter night wakening. Night wakings are noted to be full episodes of arousal, confirmed by polysomnography when available, and exclude parasomnias including but not limited confusional arousals and night terrors. Based on this working definition, we compiled the available literature to update the 2012 practice parameter from this committee as well as to guide our recommendations for further research. This working definition represents a first step in understanding the issue so that we can properly identify the occurrence of night wakings, calculate incidence at different ages, evaluate prevalence accurately, and develop and evaluate efficacious treatment options. Future large population-based samples will be necessary to fully assess the issue. We acknowledge that future modifications to this working definition may be necessary based on future work, which may advance clinical guidance and practice.

With respect to the methods employed to evaluate sleep, objective measures were lacking in most of the studies we reviewed. Notably, objective data gathered via polysomnography and actigraphy did not necessarily validate the subjective data collected from parental reports and validated sleep surveys. Many of the articles reviewed here utilized parent or caregiver reports. Reliance upon parent report of sleep disturbances has been found in both typically developing and atypically developing children to overestimate sleep problems. On the other hand, parental reports are critical to our ability to evaluate and treat sleep disturbances in children; indeed, best practices dictate that caregiver input on child symptoms or problems should be actively sought. The difference between parental report and objective data may represent misperceptions of parents but it may also reflect a higher degree of impact on parental sleep disruption caused by the perception of a higher level of intervention necessary when addressing the night wakings in a child with ASD. The need for a more involved response (e.g., a longer period of wakefulness of the parent while trying to assist the child in returning to sleep) may increase awareness of night wakings by parents who have to intervene. Thus, the impact of night waking may have a more dramatic effect on family and parental function when a greater degree of parental intervention is involved even if the frequency and duration of the actual waking is not different. Conversely, parents of children with ASD may be addressing more worrisome or difficult to manage behaviors or medical issues, leading them to underreport sleep disturbance as it might represent a secondary concern when compared with behavioral or medical issues.

As suggested by the prior practice pathway, we recommend that all children with ASD be screened for sleep problems at their annual visit with their primary provider or more frequently if there are reports of increased difficulty with typical daily activities or academic function. Parents may not necessarily discuss sleep problems during their limited time with a physician or other provider, or the sleep issues may get lower priority compared to other concerns. For these reasons, it is important for providers to query the caregiver for any sleep concerns. Furthermore, given what is known about the impact of night wakings on daytime functioning, we recommend that screening used to identify sleep problems should include queries specific to night wakings. Only four articles since the initial practice pathway addressed tools for screening with sleep questionnaires (CSHQ, CGI, Family Inventory on Sleep Habits), actigraphy, and video-somnography. Questionnaires are the most widely available tool to most clinicians outside of a sleep center, but there are no data indicating how frequently these tools are utilized in routine office visits for children with ASD. Actigraphy is a widely accessible tool and often utilized in adult sleep clinics, but has limitations in its role for identification of night wakings in children with ASD (Sitnick et al., 2008), and the gold standard of polysomnography with video is expensive and not readily available. There is still a need to encourage clinicians and families to discuss sleep problems in the clinical setting so that they can be managed.

The prior practice pathway also emphasized identifying coexisting medical conditions that can contribute to sleep problems. The prior practice pathway also recommended behavioral therapies as a first line approach. Both of these principles are also highlighted in a recent American Academy of Neurology guideline (Williams Buckley et al., 2020). Similar to the articles reviewed from the prior practice pathway on insomnia for ASD, the more recent articles we reviewed provided some evidence that medications may be efficacious in managing night wakings. However, because the findings were inconsistent and sample sizes were often limited, additional information is needed in order to understand the utility of a pharmacological approach to addressing night wakings in this population.

Further research in this area should focus on two main goals:1) better identification of night wakings in larger population studies and 2) evidence-based standards for educational/behavioral and/or pharmacologic interventions to treat night wakings in children with ASD.

Future research needs to define normative values and provide clear descriptors of how night wakings were evaluated in upcoming clinical studies. Objectively measured sleep duration and continuity is currently limited to actigraphy at home which is the less reliable, but most accessible, objective measure for measuring wake after sleep onset in comparison to polysomnography. Video polysomnography can be reliably used to measure night wakings but is currently limited to in-lab polysomnography which is expensive and takes the child out of their typical sleep environment and therefore may not accurately reflect sleep disturbances occurring at home (Penzel et al., 2018). The advent of newly available in-home monitoring with video-time lapse, permitting summary data from sleep patterns at home, may be a new avenue for monitoring and quantifiably identifying sleep disruption as well as assessing efficacy of intervention. Wearable technology for monitoring sleep parameters is becoming more sophisticated and user friendly and warrants further evaluation for efficacy especially with more objective longer-term monitoring. The utility of these monitoring devices is as yet unknown and may be considered in future studies, though data privacy limitations will need to be closely considered.

The identification of other health conditions affecting sleep highlights the need for physicians and providers to do a comprehensive evaluation of the child with sleep disturbance. Since children with decreased intellectual functioning have increased reports of night waking, it also suggests that the medical team and caregiver need to be vigilant about other potential health conditions causing sleep disturbance in a child who may not be able to communicate comparably to neuro-typical peers.

A limitation of the studies reviewed is that most were deemed low or very low on the GRADE system, with only three studies deemed of moderate quality. While the treatment trials reviewed were of low to moderate quality, they do provide some guidance. Randomized controlled trials of medications in children with ASD and insomnia are challenging due to concerns about adverse effects, cost of large studies, need for a reliable and valid outcome measure, and the potential complications of co-occurring medical conditions such as epilepsy, which may be treated with medications that may disrupt sleep. The 2012 Practice Parameter identified the role of melatonin and there is also literature that supports decreased melatonin in children with ASD as compared to their age-matched peers. The literature we reviewed identified similar findings and that extended-release melatonin showed a small to medium effect in the treatment of night wakings for children with ASD. Based on this evidence we included extended-release melatonin as part of the practice parameter. The availability of this formulation of melatonin in tablet form will limit usage in much of this population. Health care provides will need to specifically determine whether a child can swallow tablets. In patients who cannot swallow tablets, health care providers and families may consider the assistance of behavioral therapists, speech/language pathologists, and/or occupational therapists to help promote tablet swallowing. The bulk of the literature suggests the safety and efficacy of melatonin along with recommendations for behavioral and environmental interventions. There was insufficient evidence in the literature to evaluate the use of other interventions or devices (for example, medical safety beds) to address night wakings. However, children with autism may have such profound sleep disturbances so as to compel clinicians to prescribe other sleep medications without evidence-based recommendations. Analysis of existing data may be a starting point in understanding the benefits of medications on sleep since many children with autism already take medications. For example, medications such as clonidine, an alpha agonist sometimes used to treat co-occurring ADHD, may have the dual benefit of treating sleep problems. Untangling these relationships is complex, given that these medications may have variable effects on sleep and sleep architecture. A further consideration in understanding the therapeutic role of medications such as melatonin in addressing sleep disturbances in children with ASD is the timing and dosing amount. There is emerging evidence to suggest that administering a small doe of melatonin several hours prior to bedtime can be beneficial for sleep; however, based on our review of the literature, we felt there was insufficient evidence to support a conclusion about the efficacy of various dose administration strategies and timing.

Conclusion

The 2012 practice pathway for evaluation and treatment of insomnia in children with ASD is still relevant and continues to be an effective tool for clinicians. The update proposed here provides and estimate of the prevalence of night wakings in youth with ASD and the effects on daytime functioning warrants further study. A clear, universally applied definition of night wakings in future publications is needed. Our working definition is intended to serve as a jumping off point for this work. We define night wakings here as “A waking of 30 min or more following sleep onset, or frequent shorter night wakings after sleep onset that significantly disrupt the child or their family / caregiver.” The etiology of the night wakings may be multi-factorial and this fact may contribute to the difficulty in quantifying these symptoms in children with ASD. We present these data as a tool for practitioners to identify and treat insomnia in children with ASD and to emphasize that further research is necessary.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the members of the Autism Treatment Network / Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health (ATN/AIR-P) Sleep Committee for their contributions to the conceptualization of this work.

Author Contributions

AWG conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial practice pathway, reviewed all abstract and full manuscripts, drafted the original manuscript and revised and reviewed the manuscript. JGF conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the systematic literature review, evaluated treatment studies, reviewed all abstract and full manuscripts, drafted the original manuscript and revised and reviewed the manuscript.HVC, DLC, and BAM conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed abstract and full manuscripts, drafted original manuscript and revised and reviewed the manuscript.AB, JL, AMN, KS, and MW reviewed abstract and full manuscripts, drafted original manuscript and revised and reviewed the manuscript. VDA provided comments on the original manuscript and took the lead in providing extensive revisions to the manuscript based on reviewer comments. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This Network activity is/was supported by Autism Speaks and cooperative agreement UA3 MC11054 through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Research Program to the Massachusetts General Hospital. This work was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, the U.S. Government, or Autism Speaks. This work was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network (ATN) serving as the Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health (AIR-P)

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Daniel Coury is on advisory boards for BioRosa, Cognoa, GW Biosciences, Quadrant Biosciences and Stalicla; and has received research grant support from GW Biosciences, Stalicla and Stemina Biosciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aathira, R., Gulati, S., Tripathi, M., Shukla, G., Chakrabarty, B., Sapra, S., Dang, N., Gupta, A., Kabra, M., & Pandey, R. M. (2017). Prevalence of sleep abnormalities in indian children with autism spectrum disorder: A cross-sectional study. Pediatric Neurology,74, 62–67. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.05.019 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel, E. A., Schwichtenberg, A. J., Brodhead, M. T., & Christ, S. L. (2018). Sleep and challenging behaviors in the context of intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,48(11), 3871–3884. 10.1007/s10803-018-3648-0 10.1007/s10803-018-3648-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, K. W., Molloy, C., Weiss, S. K., Reynolds, A., Goldman, S. E., Burnette, C., Clemons, T., Fawkes, D., & Malow, B. A. (2012). Effects of a standardized pamphlet on insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics,130(Suppl 2), 139–144. 10.1542/peds.2012-0900K 10.1542/peds.2012-0900K [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allik, H., Larsson, J.-O., & Smedje, H. (2006). Insomnia in school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. BMC Psychiatry,6, 18. 10.1186/1471-244X-6-18 10.1186/1471-244X-6-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allik, H., Larsson, J. O., & Smedje, H. (2006b). Sleep patterns of school-age children with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,36(5), 585–595. 10.1007/s10803-006-0099-9 10.1007/s10803-006-0099-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders, T. F., Iosif, A. M., Schwichtenberg, A. J., Tang, K., & Goodlin-Jones, B. L. (2011). Six-month sleep-wake organization and stability in preschool-age children with autism, developmental delay, and typical development. Behavioral Sleep Medicine,9(2), 92–106. 10.1080/15402002.2011.557991 10.1080/15402002.2011.557991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders, T., Iosif, A. M., Schwichtenberg, A. J., Tang, K., & Goodlin-Jones, B. (2012). Sleep and daytime functioning: A short-term longitudinal study of three preschool-age comparison groups. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities,117(4), 275–290. 10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.275 10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyash, H. F., Preece, P., Morton, R., & Cortese, S. (2015). Melatonin for sleep disturbance in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: Prospective observational naturalistic study. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics,15(6), 711–717. 10.1586/14737175.2015.1041511 10.1586/14737175.2015.1041511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. K., & Richdale, A. L. (2015). Sleep Patterns in adults with a diagnosis of high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Sleep,38(11), 1765–1774. 10.5665/sleep.5160 10.5665/sleep.5160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. K., Richdale, A. L., Hazi, A., & Prendergast, L. A. (2017). Assessing the dim light melatonin onset in adults with autism spectrum disorder and no comorbid intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,47(7), 2120–2137. 10.1007/s10803-017-3122-4 10.1007/s10803-017-3122-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, S., Bender, A. M., Wickenheiser, H., Naylor, A., Clarke, M., Samuels, C. H., & Werthner, P. (2019). Differences in sleep patterns, sleepiness, and physical activity levels between young adults with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing controls. Developmental Neurorehabilitation,22(3), 164–173. 10.1080/17518423.2018.1501777 10.1080/17518423.2018.1501777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, R. B., Quan, S. F., Abreu, A. R., Bibbs, M. L., DelRoss, L., Harding, S. M., et al. (2020). The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications, version 2.6. Darien, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

- Bruni, O., Ferri, R., Vittori, E., Novelli, L., Vignati, M., Porfirio, M. C., Aricò, D., Bernabei, P., & Curatolo, P. (2007). Sleep architecture and NREM alterations in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Sleep,30(11), 1577–1585. 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1577 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, A. W., Sassower, K., Rodriguez, A. J., Jennison, K., Wingert, K., Buckley, J., Thurm, A., Sato, S., & Swedo, S. (2011). An open label trial of donepezil for enhancement of rapid eye movement sleep in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology,21(4), 353–357. 10.1089/cap.2010.0121 10.1089/cap.2010.0121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodulu, K., & Durand, M. (2004). Reducing bedtime disturbance and night waking using positive bedtime routines and sleep restriction. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities,19(3), 130–139. 10.1177/10883576040190030101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi, F., Giannotti, F., Sebastiani, T., Panunzi, S., & Valente, D. (2012). Controlled-release melatonin, singly and combined with cognitive behavioural therapy, for persistent insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Sleep Research,21(6), 700–709. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01021.x 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier, J. L., Speechley, K. N., Steele, M., Norman, R., Stringer, B., & Nicolson, R. (2005). Parental perception of sleep problems in children of normal intelligence with pervasive developmental disorders: Prevalence, severity, and pattern. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,44(8), 815–822. 10.1097/01.chi.0000166377.22651.87 10.1097/01.chi.0000166377.22651.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahaye, J., Kovacs, E., Sikora, D., Hall, T. A., Orlich, F., Clemons, T. E., Van Der Weerd, E., Glick, L., & Kuhlthau, K. (2014). The relationship between Health-related quality of life and sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders,8(3), 292–303. 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.12.015 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.12.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delemere, E., & Dounavi, K. (2018). Parent-Implemented bedtime fading and positive routines for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,48(4), 1002–1019. 10.1007/s10803-017-3398-4 10.1007/s10803-017-3398-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diomedi, M., Curatolo, P., Scalise, A., Placidi, F., Caretto, F., & Gigli, G. L. (1999). Sleep abnormalities in mentally retarded autistic subjects: Down’s syndrome with mental retardation and normal subjects. Brain & Development,21(8), 548–553. 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00077-7 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00077-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doo, S., & Wing, Y. K. (2006). Sleep problems of children with pervasive developmental disorders: Correlation with parental stress. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology,48(8), 650–655. 10.1017/S001216220600137X 10.1017/S001216220600137X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, T. W., Krishna, J., Klingemier, E., Beukemann, M., Nawabit, R., & Ibrahim, S. (2017). A Randomized, crossover trial of a novel sound-to-sleep mattress technology in children with autism and sleep difficulties. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine,13(1), 95–104. 10.5664/jcsm.6398 10.5664/jcsm.6398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli-Carminati, G., Deriaz, N., & Bertschy, G. (2009). Melatonin in treatment of chronic sleep disorders in adults with autism: a retrospective study. Swiss Medical Weekly,139(19–20), 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garstang, J., & Wallis, M. (2006). Randomized controlled trial of melatonin for children with autistic spectrum disorders and sleep problems. Child: Care, Health and Development,32(5), 585–589. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00616.x 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, F., Cortesi, F., Cerquiglini, A., & Bernabei, P. (2006). An open-label study of controlled-release melatonin in treatment of sleep disorders in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,36(6), 741–752. 10.1007/s10803-006-0116-z 10.1007/s10803-006-0116-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, F., Cortesi, F., Cerquiglini, A., Miraglia, D., Vagnoni, C., Sebastiani, T., & Bernabei, P. (2008). An investigation of sleep characteristics, EEG abnormalities and epilepsy in developmentally regressed and non-regressed children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,38(10), 1888–1897. 10.1007/s10803-008-0584-4 10.1007/s10803-008-0584-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S. E., Adkins, K. W., Calcutt, M. W., Carter, M. D., Goodpaster, R. L., Wang, L., Shi, Y., Burgess, H. J., Hachey, D. L., & Malow, B. A. (2014). Melatonin in children with autism spectrum disorders: Endogenous and pharmacokinetic profiles in relation to sleep. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,44(10), 2525–2535. 10.1007/s10803-014-2123-9 10.1007/s10803-014-2123-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S. E., Alder, M. L., Burgess, H. J., Corbett, B. A., Hundley, R., Wofford, D., Fawkes, D. B., Wang, L., Laudenslager, M. L., & Malow, B. A. (2017). Characterizing sleep in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,47(6), 1682–1695. 10.1007/s10803-017-3089-1 10.1007/s10803-017-3089-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S. E., Richdale, A. L., Clemons, T., & Malow, B. A. (2012). Parental sleep concerns in autism spectrum disorders: Variations from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,42(4), 531–538. 10.1007/s10803-011-1270-5 10.1007/s10803-011-1270-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S. E., Surdyka, K., Cuevas, R., Adkins, K., Wang, L., & Malow, B. A. (2009). Defining the sleep phenotype in children with autism. Developmental Neuropsychology,34(5), 560–573. 10.1080/87565640903133509 10.1080/87565640903133509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlin-Jones, B. L., Sitnick, S. L., Tang, K., Liu, J., & Anders, T. F. (2008). The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire in toddlers and preschool children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP,29(2), 82–88. 10.1097/dbp.0b013e318163c39a 10.1097/dbp.0b013e318163c39a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringras, P., Nir, T., Breddy, J., Frydman-Marom, A., & Findling, R. L. (2017). Efficacy and Safety of Pediatric Prolonged-Release Melatonin for Insomnia in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,56(11), 948-957.e4. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.414 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G., Oxman, A., Akl, E., et al. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction–GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.,64(4), 383–394. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare, D. J., Jones, S., & Evershed, K. (2006). Objective investigation of the sleep-wake cycle in adults with intellectual disabilities and autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR,50(Pt 10), 701–710. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00830.x 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering, E., Epstein, R., Elroy, S., Iancu, D. R., & Zelnik, N. (1999). Sleep patterns in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,29(2), 143–147. 10.1023/a:1023092627223 10.1023/a:1023092627223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, D., Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., & Riggs, M. L. (2013). Relationship between children’s sleep and mental health in mothers of children with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,43(4), 956–963. 10.1007/s10803-012-1639-0 10.1007/s10803-012-1639-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., Gilliam, J. E., & Lopez-Wagner, M. C. (2006). Sleep problems in children with autism and in typically developing children. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities,21(3), 146–152. 10.1177/10883576060210030301 10.1177/10883576060210030301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honomichl, R. D., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., Burnham, M., Gaylor, E., & Anders, T. F. (2002). Sleep patterns of children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,32(6), 553–561. 10.1023/a:1021254914276 10.1023/a:1021254914276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, J. S., Gringras, P., Blair, P. S., Scott, N., Henderson, J., Fleming, P. J., & Emond, A. M. (2014). Sleep patterns in children with autistic spectrum disorders: A prospective cohort study. Archives of Disease in Childhood,99(2), 114–118. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304083 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranzo, A. (2020). Sleep and neurological autoimmune diseases. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology,45(1), 129–140. 10.1038/s41386-019-0463-z 10.1038/s41386-019-0463-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. R., Turner, K. S., Foldes, E., Brooks, M. M., Kronk, R., & Wiggs, L. (2013). Behavioral parent training to address sleep disturbances in young children with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot trial. Sleep Medicine,14(10), 995–1004. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.05.013 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, T., Shui, A. M., Johnson, C. R., Richdale, A. L., Reynolds, A. M., Scahill, L., & Malow, B. A. (2018). Modification of the children’s sleep habits questionnaire for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,48(8), 2629–2641. 10.1007/s10803-018-3520-2 10.1007/s10803-018-3520-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelmanson, I. A. (2020). Sleep disturbances and their associations with emotional/behavioural problems in 5-year-old boys with autism spectrum disorders. Early Child Development and Care,190(2), 236–251. 10.1080/03004430.2018.1464622 10.1080/03004430.2018.1464622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirouri, S., Kalejahi, P., & Noorazar, S. G. (2016). Plasma levels of serotonin, gastrointestinal symptoms, and sleep problems in children with autism. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences,46(6), 1765–1772. 10.3906/sag-1507-68 10.3906/sag-1507-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R., & Johnson, C. (2014). Using a behavioral treatment package for sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child & Family Behavior Therapy,36(3), 204–221. 10.1080/07317107.2014.934171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak, P., Goodlin-Jones, B., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Croen, L. A., & Hansen, R. L. (2008). Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical development: A population-based study. Journal of Sleep Research,17(2), 197–206. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00650.x 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00650.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, R., Kessler, R., Buckley, A. W., Rodriguez, A., Farmer, C., Thurm, A., Swedo, S., & Felt, B. (2015). Evaluation of periodic limb movements in sleep and iron status in children with autism. Pediatric Neurology,53(4), 343–349. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.06.014 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loring, W. A., Johnston, R., Gray, L., Goldman, S. E., & Malow, B. A. (2016). A brief behavioral intervention for insomnia in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology,4, 112–124. 10.1037/cpp0000141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Louveau, A., Smirnov, I., Keyes, T. J., et al. (2015). Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature,523(7560), 337–341. 10.1038/nature14432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Furnier, S. M., Hallas, L., Hall-Lande, J., Hudson, A., Hughes, M. M., Patrick, M., Pierce, K., Poynter, J. N., Salinas, A., Shenouda, J., Vehorn, A., Warren, Z., Constantino, J. N., … Cogswell, M. E. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, united states, 2018. morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C. 2002),70(11), 1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow, B., Adkins, K. W., McGrew, S. G., Wang, L., Goldman, S. E., Fawkes, D., & Burnette, C. (2012). Melatonin for sleep in children with autism: A controlled trial examining dose, tolerability, and outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,42(8), 1729–1738. 10.1007/s10803-011-1418-3 10.1007/s10803-011-1418-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow, B. A., Adkins, K. W., Reynolds, A., Weiss, S. K., Loh, A., Fawkes, D., Katz, T., Goldman, S. E., Madduri, N., Hundley, R., & Clemons, T. (2014). Parent-based sleep education for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,44(1), 216–228. 10.1007/s10803-013-1866-z 10.1007/s10803-013-1866-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow, B. A., Byars, K., Johnson, K., Weiss, S., Bernal, P., Goldman, S. E., Panzer, R., Coury, D. L., Glaze, D. G., Sleep Committee of the Autism Treatment Network. (2012). A practice pathway for the identification, evaluation, and management of insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics,130(Suppl 2), S106–S124. 10.1542/peds.2012-0900I 10.1542/peds.2012-0900I [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow, B. A., Crowe, C., Henderson, L., McGrew, S. G., Wang, L., Song, Y., & Stone, W. L. (2009). A sleep habits questionnaire for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Neurology,24(1), 19–24. 10.1177/0883073808321044 10.1177/0883073808321044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow, B. A., Katz, T., Reynolds, A. M., Shui, A., Carno, M., Connolly, H. V., Coury, D., & Bennett, A. E. (2016). Sleep Difficulties and Medications in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Registry Study. Pediatrics,137(Suppl 2), S98–S104. 10.1542/peds.2015-2851H 10.1542/peds.2015-2851H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maras, A., Schroder, C. M., Malow, B. A., Findling, R. L., Breddy, J., Nir, T., Shahmoon, S., Zisapel, N., & Gringras, P. (2018). Long-term efficacy and safety of pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology,28(10), 699–710. 10.1089/cap.2018.0020 10.1089/cap.2018.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, M. O., & Petroski, G. F. (2015). Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: Examining the contributions of sensory over-responsivity and anxiety. Sleep Medicine,16(2), 270–279. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.11.006 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, M. O., & Sohl, K. (2016). Sleep and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,46(6), 1906–1915. 10.1007/s10803-016-2723-7 10.1007/s10803-016-2723-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue, L. M., Flick, L. H., Twyman, K. A., & Xian, H. (2017). Gastrointestinal dysfunctions as a risk factor for sleep disorders in children with idiopathic autism spectrum disorder: A retrospective cohort study. Autism : THe International Journal of Research and Practice,21(8), 1010–1020. 10.1177/1362361316667061 10.1177/1362361316667061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrazad-Saber, Z., Kheirouri, S., & Noorazar, S. G. (2018). Effects of l-carnosine supplementation on sleep disorders and disease severity in autistic children: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology,123(1), 72–77. 10.1111/bcpt.12979 10.1111/bcpt.12979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miano, S., Bruni, O., Elia, M., Trovato, A., Smerieri, A., Verrillo, E., Roccella, M., Terzano, M. G., & Ferri, R. (2007). Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder: A questionnaire and polysomnographic study. Sleep Medicine,9(1), 64–70. 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.01.014 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming, X., Gordon, E., Kang, N., & Wagner, G. C. (2008). Use of clonidine in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain & Development,30(7), 454–460. 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.007 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming, X., Sun, Y. M., Nachajon, R. V., Brimacombe, M., & Walters, A. S. (2009). Prevalence of parasomnia in autistic children with sleep disorders. Clinical Medicine. Pediatrics,3, 1–10. 10.4137/cmped.s1139 10.4137/cmped.s1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasingharao, K., Pradhan, B., & Navaneetham, J. (2017). Efficacy of structured yoga intervention for sleep, gastrointestinal and behaviour problems of ASD Children: An exploratory study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR,11(3), VC01–VC06. 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25894.9502 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25894.9502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, J. A., Spirito, A., & McGuinn, M. (2000). The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep,23(8), 1043–1051. 10.1093/sleep/23.8.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyane, N. M., & Bjorvatn, B. (2005). Sleep disturbances in adolescents and young adults with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism : THe International Journal of Research and Practice,9(1), 83–94. 10.1177/1362361305049031 10.1177/1362361305049031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavonen, E. J., Nieminen-von Wendt, T., Vanhala, R., Aronen, E. T., & von Wendt, L. (2003). Effectiveness of melatonin in the treatment of sleep disturbances in children with Asperger disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology,13(1), 83–95. 10.1089/104454603321666225 10.1089/104454603321666225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzel, T., Schöbel, C., & Fietze, I. (2018). New technology to assess sleep apnea: wearables, smartphones, and accessories. F1000Research,7, 413. 10.12688/f1000research.13010.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, H. E., McGrew, S. G., Artibee, K., Surdkya, K., Goldman, S. E., Frank, K., Wang, L., & Malow, B. A. (2009). Parent-based sleep education workshops in autism. Journal of Child Neurology,24(8), 936–945. 10.1177/0883073808331348 10.1177/0883073808331348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A. M., Soke, G. N., Sabourin, K. R., Hepburn, S., Katz, T., Wiggins, L. D., Schieve, L. A., & Levy, S. E. (2019). Sleep problems in 2- to 5-year-olds with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental delays. Pediatrics,143(3), e20180492. 10.1542/peds.2018-0492 10.1542/peds.2018-0492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richdale, A. L., Baker, E., Short, M., & Gradisar, M. (2014). The role of insomnia, pre-sleep arousal and psychopathology symptoms in daytime impairment in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Sleep Medicine,15(9), 1082–1088. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.05.005 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richdale, A. L., & Schreck, K. A. (2009). Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Medicine Reviews,13(6), 403–411. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.02.003 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, P. G., Posar, A., Parmeggiani, A., Pipitone, E., & D’Agata, M. (1999). Niaprazine in the treatment of autistic disorder. Journal of Child Neurology,14(8), 547–550. 10.1177/088307389901400814 10.1177/088307389901400814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnick, S. L., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., & Anders, T. F. (2008). The use of actigraphy to study sleep disorders in preschoolers: Some concerns about detection of nighttime awakenings. Sleep,31(3), 395–401. 10.1093/sleep/31.3.395 10.1093/sleep/31.3.395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuttard, L., Beresford, B., Clarke, S., Beecham, J., & Curtis, J. (2015). A preliminary investigation into the effectiveness of a group-delivered sleep management intervention for parents of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities : JOID,19(4), 342–355. 10.1177/1744629515576610 10.1177/1744629515576610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani, P., Lindberg, N., Nieminen-von Wendt, T., von Wendt, L., Alanko, L., Appelberg, B., & Porkka-Heiskanen, T. (2003). Insomnia is a frequent finding in adults with asperger syndrome. BMC Psychiatry,3, 12. 10.1186/1471-244X-3-12 10.1186/1471-244X-3-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani, P., Lindberg, N., Nieminen-von Wendt, T., von Wendt, L., Virkkala, J., Appelberg, B., & Porkka-Heiskanen, T. (2004). Sleep in young adults with asperger syndrome. Neuropsychobiology,50(2), 147–152. 10.1159/000079106 10.1159/000079106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M. A., Schreck, K. A., & Mulick, J. A. (2012). Sleep disruption as a correlate to cognitive and adaptive behavior problems in autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities,33(5), 1408–1417. 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.03.013 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]