Abstract

Diseases caused by gammaherpesviruses such as Epstein-Barr virus are a major health concern, and there is significant interest in developing vaccines against this class of viral infections. However, the requirements for effective control of gammaherpesvirus infection are only poorly understood. The recent development of the murine herpesvirus MHV-68 model provides an experimental tool to dissect the immune response to gammaherpesvirus infections. In this study, we investigated the impact of priming T cells specific for class I- and class II-restricted epitopes on the acute phase of the infection and the subsequent establishment of latency and infectious mononucleosis. The data show that vaccination with either major histocompatibility complex class I- or class II-restricted T-cell epitopes derived from lytic cycle proteins significantly reduced lung viral titers during the acute infection. Moreover, the peak level of latently infected spleen cells was significantly reduced following vaccination with immunodominant CD8+ T-cell epitopes. However, this vaccination approach did not prevent the long-term establishment of latency or the development of the infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome in infected mice. Thus, the virus is able to establish latency efficiently despite strong immunological control of the lytic infection.

Gammaherpesviruses (γHV) cause lifelong infection and diseases in many species. The human γHV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, are associated with several malignant human diseases including Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma (3, 29). Vaccines against these widely disseminated viruses are keenly sought to prevent the associated diseases. Most EBV vaccine studies have been focused on gp350/220, which elicits virus-neutralizing antibody (10, 11, 24). However, this vaccination approach does not induce a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response against infected cells, which is crucial for the control of the virus (30). Vaccines against latency-associated proteins containing CTL epitopes are currently being tested. But the fact that more than 60% of the epitopes recognized by EBV-specific CTL clones are located in regions outside the latent EBNA and LMP-1 proteins suggests that any EBV vaccine based on CTL epitopes needs to include other regions of the viral genome such as the lytic cycle genes (20, 32).

EBV studies have been limited to clinically apparent EBV infection in humans, and studies of acute infection are limited to infectious mononucleosis (IM) patients due to the lack of a suitable animal model (26, 36). However, the recently identified murine herpesvirus 68 (MHV-68), a type 2 γHV, shows pathobiological features similar to those of EBV and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and represents a useful small-animal model of γHV infection (26, 39, 45). Intranasal administration of MHV-68 to mice results in an acute infection in lung epithelial cells followed by latent infection in B cells, macrophages, and lung epithelium (37, 40, 46). In addition, there is splenomegaly and an expansion of activated CD8+ T cells in blood, characteristics in common with EBV-induced IM (38, 41). Many of these activated cells have been shown to be of a T-cell receptor Vβ4+/CD8+ phenotype irrespective of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) haplotype (8, 41). CD8+ T cells have been shown to be important in the control of both acute and latent infections, and several lytic cycle CTL epitopes including the dominant epitopes ORF6487–495/Db and ORF61524–531/Kb (2, 9, 33), have been defined recently. Interestingly, these epitopes are expressed not only during the acute lung infection, but also after the establishment of latency in the spleen due to continual low level of viral reactivation (22).

Studies by Stewart et al. showed that vaccination against the major membrane antigen gp150, the MHV-68 homologue of EBV gp350/220, reduced the peak numbers of latently infected cells (36). However, latency was still established in this system. Since lytic-phase CD8+ T-cell epitopes are expressed during the acute infection and also after latency has been established (22), we hypothesized that vaccination against lytic cycle CD8+ epitopes might result in better control of both acute and latent infection. In this study, we vaccinated mice with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with defined lytic cycle CTL epitopes, including a subdominant CTL epitope from glycoprotein B (gB), the most conserved protein in the herpesvirus family (29, 35). This vaccination approach has been shown to elicit strong CTL responses and also limits the generation of antipeptide antibody (16, 17, 23). The data show that dendritic cell immunization against lytic cycle MHV-68 T-cell epitopes not only leads to partial protection against acute infection in the lungs but also alters the early events in the establishment of latency in the spleen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (Bar Harbor, Maine). H-2 I-Ab-deficient B6C2D mice (12) were bred at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital under license from GenPharm International (Mountain View, Calif.). Mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions until MHV-68 infection and in BL3 containment after infection.

Cell lines.

L-cell lines were grown in complete tumor medium (CTM) containing 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C with 10% CO2 (18). L cells transfected with the Ab, Kb, or Db MHC genes have been described previously (7, 27). NIH 3T3 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) containing 10% fetal calf serum. All adherent cells were removed with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) prior to use in the assays.

Generation of T-cell hybridomas.

T-cell hybridomas were generated from MHV-68-infected mice in three independent fusions as described previously (22, 42, 47). In the first fusion, mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) were harvested from C57BL/6 mice 9 days after MHV-68 infection and expanded in vitro for 5 days in the presence of 10 U of recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) per ml. Blast cells were then enriched by passage over a Ficoll bed and fused with the BWα−β− fusion partner as described previously (47). After the fusion, cells were cultured under limiting dilution conditions and clonal hybridomas were tested for viral specificity, using MHV-68-infected C57BL/6 spleen cells or L-cell transfectants (L-Kb, L-Db, and L-I-Ab), by assaying IL-2 production in a standard bioassay (48). The first fusion led to the identification of the gp15067–83/I-Ab-specific hybridoma (hybridoma 4211). In the second and third fusions, MHC class II-deficient B6C2D mice were used to specifically generate class I-restricted T-cell hybridomas (22). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BAL) and MLN were harvested from B6C2D mice 9 days after MHV-68 infection, and the cells expanded as described above. Activated cells were fused with the BWZ.36 fusion partner, which expresses the lacZ gene under the control of the minimal IL-2 promoter and NF-AT-responsive enhancer sequence (19, 31). Antigen specificity was determined in a single cell 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) assay as described previously (42). Briefly, 105 hybridomas were cultured with 105 virus-infected or peptide (10 μg/ml)-loaded presenting cells in flat-bottomed microtiter plates for 18 h. Cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed with cold 2% formaldehyde–0.2% glutaraldehyde (100 μl/well) for 5 min. The cells were washed again with PBS and then overlaid with PBS containing 1 mg of X-Gal per ml, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, and 2 mM MgCl2. After 6 to 18 h of incubation, the numbers of blue cells per well were counted in an inverted tissue culture microscope. Fusions 2 and 3 led to the identification of the MHC class I-restricted hybridomas.

Virus stocks and virus infections.

The original stock of MHV-68 (clone G2.4) was obtained from A. A. Nash (Edinburgh, United Kingdom) as a cell-free lysate derived from infected baby hamster kidney cells. This was then propagated in owl monkey kidney fibroblasts (ATCC 1566CRL; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) and titrated on NIH 3T3 cells (2). Mice were anesthetized with Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) and infected intranasally with 400 PFU of MHV-68 (in 40 μl PBS) at 8 to 12 weeks of age. BAL and MLN were then harvested at day 9 after infection (day 11 for intracellular gamma interferon [IFN-γ] staining). The inflammatory cells in BAL were first absorbed on plastic petri dishes (Falcon, Lincoln Park, N.J.) for 60 min at 37°C to remove adherent cells. Erythrocytes were lysed with Gey’s solution for all the tissue samples.

L-cell lines were infected with MHV-68 (multiplicity of infection [MOL] = 1) in 1 ml CTM at 37°C for 2 h. The cells were washed three times following infection and then used immediately in the experiments. Vaccinia virus recombinants expressing either the gB or the membrane-associated protein (gp150) of MHV-68, vac-gB and vac-gp150, were kind gifts from J. P. Stewart (Edinburgh, United Kingdom) and were propagated in B143.TK− cells (ATCC 8303CRL) (34–36). Cell lines were infected with vac-gB, vac-gp150, or wild-type vaccinia virus (MOI = 5) in 1 ml of CTM at 37°C for 1 h. The cells were then diluted into 10 ml of CTM, incubated for 3 h, and given three washes before use.

Synthetic peptides.

Two sets of peptides (16-mers overlapped by 10 amino acids or 17-mers overlapped by 11 amino acids), representing the entire lengths of the predicted MHV-68 gB and gp150 proteins (34, 35) were synthesized by Chiron Mimotopes (Clayton, Victoria, Australia). The NP324–332 peptide (FAPGNYPAL), gp15067–83 peptide (LSNNNPTTIMRPPVAQN), gB599–614 peptide (YIYYYKNYIFEEKLNL), and four 8-mer or 9-mer gB peptides within the gB599–614 sequence were synthesized at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Center for Biotechnology on an Applied Biosystems (Berkeley, Calif.) model 433A peptide synthesizer. Peptide purity was evaluated by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis. The ORF61524–531 (TSINFVKI) and ORF6487–495 (AGPHNDMEI) peptides were kind gifts from P. C. Doherty (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn.). Stock solutions of peptides (1 mg/ml) were prepared in PBS.

Intracellular IFN-γ staining.

Intracellular IFN-γ staining was performed as previously described (14, 25). Freshly isolated BAL cells were incubated for 5 h (106 in 200 μl of CTM with brefeldin A [10 μg/ml] and recombinant human IL-2 [10 U/ml]) in the presence or absence of ORF61524–531, gB604–612, or gp15067–83 peptide (1 μg/ml). Stimulation with anti-CD3 antibodies served as a positive control (43.8% of CD8+ T cells secreted IFN-γ [data not shown]). Anti-mouse CD16/32 (Fc-γIII/II receptor) antibody rat anti-mouse tricolor-conjugated CD8α antibody, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-IFN-γ antibody or anti-immunoglobulin G1 isotype control antibody were all purchased from (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Following the staining, the cell samples were run on a FACScan flow cytometer and the data were analyzed with the CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.).

Generation, culture, and flow cytometry of dendritic cells.

Dendritic cells were generated from C57BL/6 mouse bone marrow cultures as described previously, with minor modifications (15). Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from femurs and tibias and subsequently depleted of erythrocytes with Gey’s solution. Cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Biowhittaker) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10 μg of gentamicin sulfate per ml and counted with cresyl violet staining (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for mononucleated cells. The cells were plated at 2.5 × 106 mononucleated cells/well in 3 ml in complete RPMI 1640 on six-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. After the incubation, the nonadherent cells were removed. Complete RPMI 1640 containing recombinant mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 1,000 U/ml; (R&D Systems) and recombinant mouse IL-4 (10 ng/ml; RDI, Flanders, N.J.) were added at 3 ml per well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C with 10% CO2 for 1 week. The culture was fed every 2 days by gently swirling the plates, aspirating 75% of the medium, and adding back fresh medium with recombinant mouse GM-CSF and recombinant mouse IL-4 on days 2, 4, and 6 of culture. On day 7, cell aggregates and nonadherent cells were harvested, and a small sample was stained by the following fluorescein conjugated antibodies: anti-I-Ab (AF6-120), anti-CD11c (HL3), anti-CD80 (16-10A1), anti-CD86 (GL1), anti-CD3 (145-2C11), and anti-CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2) (all obtained from Pharmingen). Most cells in the culture showed the distinct stellate dendritic cell morphology; 70 to 90% of the cells were MHC class II I-Ab+, 50 to 65% were CD11c+ and 50 to 75% were positive for CD80 and CD86, as determined by flow cytometry (data not shown).

Vaccination of mice.

The cultured dendritic cells were resuspended at 5 × 106/ml in serum-free RPMI 1640 containing peptide gp15067–83, ORF6487–495, ORF61524–531, gB604–612, or NP324–332 (50 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 2 to 3 h. Cells were then washed twice with balanced salt solution and resuspended at 107/ml in PBS; then 106 dendritic cells were injected into each C57BL/6 mouse intravenously. Two weeks after the injection, mice were boosted with 0.5 mg of peptide per ml in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA; 1:1 mixture, 100 μl/mouse) subcutaneously at the base of the tail.

Cytotoxicity assays.

Cytotoxicity activity was evaluated as described previously (4). To assess the priming effect of dendritic cell vaccination, spleen cells from primed mice were harvested 2 weeks after peptide boosting and restimulated for 5 days in 24-well tissue culture plates in the presence of recombinant human IL-2 (10 U/ml) and peptide (1 μg/ml). After the restimulation, titrated numbers of effector cells were cultured with peptide-pulsed and 51NaCrO4-labeled L cells for 4 h. The supernatant of the cytotoxicity cultures was collected from each well and counted with a gamma counter. The percentage of specific release was calculated as [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release)] × 100. Maximal release was determined by adding 1% Triton X-100 (t-octylphenoxypolyethoxyethanol; Sigma).

Virus assays.

Infectious virus titers in the lungs were determined by plaque assays as previously described (2, 39). Briefly, lungs from three mice of each group were homogenized and frozen at −70°C prior to assay. Serial dilutions of homogenized lung tissues were added to NIH 3T3 monolayers in a minimal volume and left to adsorb for 2 h before overlaying with carboxymethyl cellulose. Plaques were counted after methanol fixation and Giemsa staining of the monolayers following 5 days of incubation. The frequency of latently infected (or virus-associated cells) was measured by using an infective center assay as previously described (2). Briefly, titrated numbers of spleen cells from infected mice were added onto NIH 3T3 cell monolayers and overlaid with carboxymethyl cellulose after overnight incubation. Following 6 days of culture, plaques were quantitated after methanol fixation and Giemsa staining.

RESULTS

Identification of MHV-68 CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell epitopes.

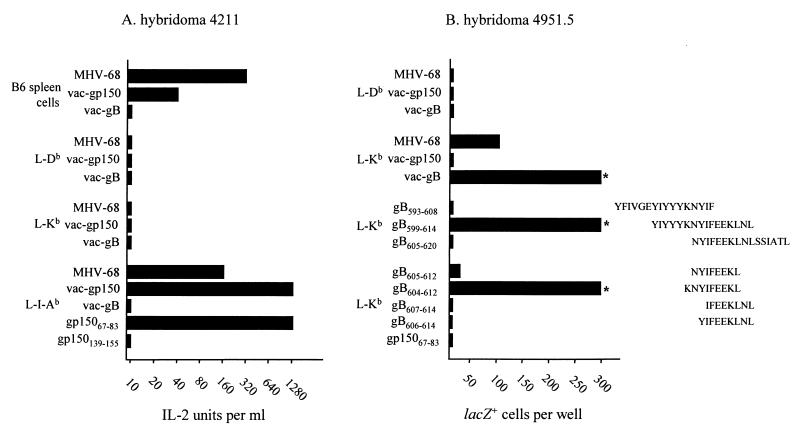

Previous studies by Stevenson et al. have identified two dominant MHC class I-restricted epitopes that drive the primary CD8+ T-cell response to MHV-68 infection in C57BL/6 mice (33). Both of these epitopes, ORF6487–495/Db and ORF61524–531/Kb, are derived from early lytic cycle genes. To determine whether additional epitopes contributed to the T-cell response to MHV-68 infection in H-2b mice, T-cell hybridomas were generated from the MLN of MHV-68-infected C57BL/6 and H-2 I-Ab-deficient B6C2D mice (class II-negative mice are severely deficient in functional CD4+ T cells and were used to ensure that class I-restricted T-cell hybridomas were recovered). The hybridomas were initially screened for reactivity to MHV-68-infected C57BL/6 spleen cells, and the reactive hybridomas were then rescreened on MHV-68-infected L cells transfected with either Kb, Db, or I-Ab (data not shown). Altogether, 10 class I restricted hybridomas (derived from B6C2D mice) and 13 class II (I-Ab)-restricted hybridomas (derived from C57BL/6 mice) were obtained. Two of the Db-restricted hybridomas responded to the ORF6487–495 peptide, and one of the Kb-restricted hybridomas reacted to the ORF61524–531 peptide. We also screened these hybridomas by using vac-gB and vac-gp150. These studies identified one hybridoma (4211) which responded to vac-gp150 in the context of I-Ab (Fig. 1A) and two hybridomas (4951.5 and 4722.2) which responded to vac-gB in the context of Kb (Fig. 1B; only data for hybridoma 4951.5 are shown). Overlapping 17-mer or 16-mer peptides scanning the entire gp150 protein and gB proteins were then used to identify two peptides (gp15067–83 and gB599–614) representing these epitopes (Fig. 1). To define the core Kb epitope within the gB599–614 peptide, the 4951.5 hybridoma was screened for reactivity to truncated peptides. As shown in Fig. 1B, a nine-amino-acid peptide (gB604–612) induced maximal stimulation of the 4951.5 hybridoma. Interestingly, the gB604–612 peptide does not contain a classical Kb binding motif, ----[F/Y]--[L/M/I/V/C], although it does contain a C-terminal leucine anchor (28).

FIG. 1.

Identification of T-cell hybridomas specific for gp15067–83/Ab and gB604–612/Kb. Hybridomas 4211 (A) and 4951.5 (B) were tested for reactivity to C57BL/6 spleen cells or L cells that were infected with either MHV-68 or vaccinia virus recombinants-encoded gB or gp150 or were pulsed with the indicated peptides. The hybridoma responses were measured by an IL-2 assay (hybridoma 4211) or single-cell X-Gal assay (hybridoma 4951.5) as described in Materials and Methods. The asterisks in panel B indicate that the hybridoma response was greater than 300 lacZ+ cells per well. A third hybridoma, 4722.2, gave the same pattern of response as 4951.5 (data not shown). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

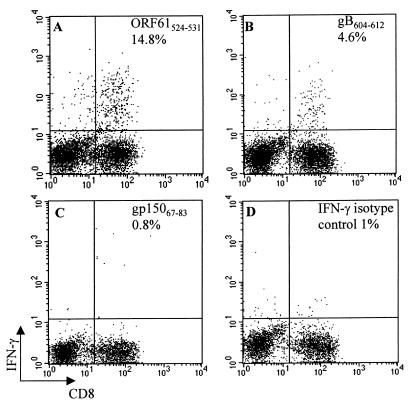

Since the gB604–612/Kb-specific hybridoma was generated in MHC class II-deficient mice, it was possible that this epitope did not contribute to the T-cell response in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. To investigate this possibility, we used an intracellular IFN-γ assay to look for gB604–612/Kb-specific T cells in the lungs of acutely MHV-68-infected C57BL/6 mice. Consistent with a previous report, approximately 14% of the CD8+ T cells in BAL were specific for the dominant ORF61524–531/Kb peptide (Fig. 2A) (33). In addition, 4 to 5% of CD8+ T cells in BAL responded to the gB604–612 peptide by producing IFN-γ (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that this epitope is involved in the CD8+ T-cell response to MHV-68 in C57BL/6 mice. Background IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells in these experiments, as measured with a control I-Ab-restricted gp15067–83 peptide (Fig. 2C) and an isotype control antibody (Fig. 2D), was approximately 1%. We were also able to demonstrate cytolytic activity in the lung to L-Kb target cells infected with vac-gB in a chromium release assay (data not shown). These data indicate that the gB604–612/Kb epitope contributes to an effector CD8+ T-cell response to MHV-68 infection in C57BL/6 mice but is subdominant to the ORF61524–531/Kb epitope.

FIG. 2.

gB604–612 is a subdominant epitope for CD8+ T cells during the acute MHV-68 infection. BAL was harvested from C57BL/6 mice at day 11 postinfection and incubated with ORF61524–531 (A), gB604–612 (B), or gp15067–83 (C). The frequency of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells specific for each epitope was measured by intracellular IFN-γ staining as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of IFN-γ+ cells among CD8+ T cells is indicated in each panel. The cells were also stained with an immunoglobulin G isotype control antibody (D).

Dendritic cell vaccination efficiently primed CD8+ T cells in C57BL/6 mice.

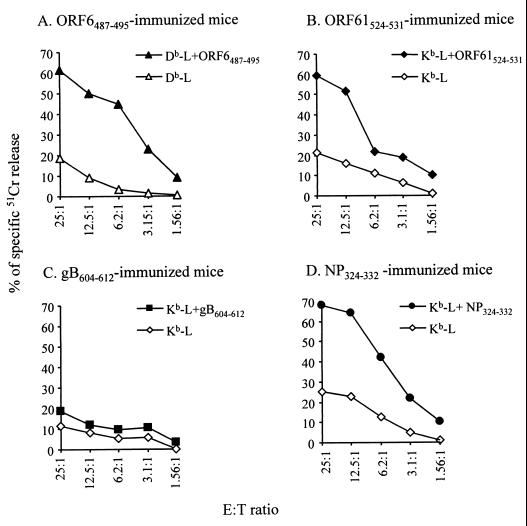

CD8+ T cells have been shown to play a role in the control of both the acute and latent phases of MHV-68 infection. Therefore, it was of interest to determine the impact of prior vaccination with lytic cycle ORF6487–495, ORF61524–531, and gB604–612 epitopes on the course of infection. For these studies, we took advantage of a vaccination approach in which in vitro-cultured dendritic cells are pulsed with antigen peptides and injected into mice intravenously (16, 23). Thus, C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with dendritic cells pulsed with either ORF6487–495, ORF61524–531, gB604–612, or NP324–332 (a control Sendai virus Kb-restricted peptide) and boosted 2 weeks later with the same peptides in IFA. Mice were also vaccinated with the I-Ab-restricted gp15067–83 peptide, to determine the effect of CD4+ T-cell priming on the course of MHV-68 infection. To confirm that mice were primed against the peptides, spleen cells harvested 2 weeks after the peptide boost were restimulated in vitro for 5 days and then tested for peptide-specific lytic activity against target cells pulsed with the vaccinating peptide. As shown in Fig. 3, mice primed with the ORF6487–495, ORF61524–531, and NP324–332 peptides showed strong lytic activity for their peptide-pulsed target cells, whereas unvaccinated spleen cells or spleen cells vaccinated with unpulsed dendritic cells showed no peptide-specific lytic activity (data not shown). However, we could not reliably detect lytic activity against the subdominant gB604–612/Kb epitope with this vaccination approach.

FIG. 3.

Dendritic cell vaccination efficiently primes CD8+ T cells. Spleens were harvested from the vaccinated mice 2 weeks after peptide boosting. Spleen cells were restimulated in vitro with the immunizing peptide for 5 days. Peptide-specific CTL activities in the spleen cell culture were then measured by 51Cr release assay as described in Materials and Methods. L cells with or without peptide pulsing were used as CTL targets, as indicated. Data are representative of three independent experiments. E:T, effector cell:target cell.

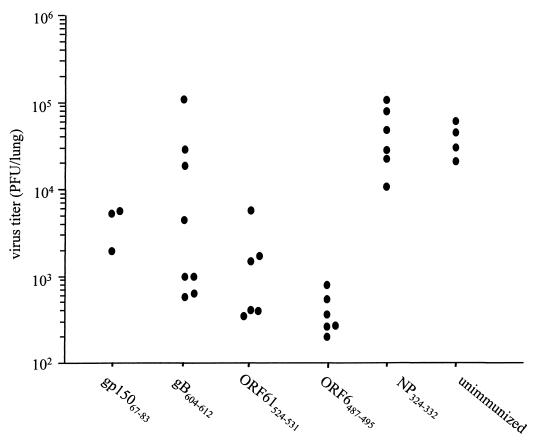

Protective effect of dendritic cell vaccination on the acute-phase MHV-68 infection.

To assess the effect of peptide vaccination on the acute phase of MHV-68 infection, mice were intranasally challenged with 400 PFU of MHV-68 2 weeks after the peptide-IFA boost. Lung virus titers were assayed 6 days postinfection, a time point when the lung virus titer peaks in infected animals. As shown in Fig. 4, mice vaccinated with either the ORF6487–495 or ORF61524–531 peptide showed a 10- to 100-fold reduction in lung virus titers relative to unvaccinated mice or mice vaccinated with the control Sendai virus NP324–332 peptide (P < 0.05 in a Student t test). The ORF6487–495 peptide had the greatest efficacy, consistent with the immunodominant status of the ORF6487–495/Db epitope. In contrast, the gB604–612-vaccinated mice had a range of viral titers, with some mice showing strong protection and other mice showing no protection (Fig. 4). Thus, although we could not reliably recover gB604–612/Kb-specific CTL activity in the spleen from the mice vaccinated with the gB604–612 peptide, there was a clear effect on the acute infection in some animals. The differences between individual animals are most likely due to variation in the efficacy of priming. Surprisingly, vaccination of the mice with the MHC class II-restricted gp15067–83 peptide also resulted in a 10-fold reduction in lung viral titers (Fig. 4) (P < 0.05 in a Student t test). Taken together, the data demonstrate that vaccination with lytic cycle CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell epitopes results in a significant reduction in the viral load during the acute phase of the infection.

FIG. 4.

Lung virus titers at day 6 after MHV-68 infection in C57BL/6 mice vaccinated with various epitopes. Virus titers in the lungs were measured by plaque assay as described in Materials and Methods, and each point represents the titer from an individual mouse. The data are combined from two independent experiments. The reduction in virus titers in the ORF6487–495-, ORF61524–531-, and gp15067–83-vaccinated animals were significantly different from either the Sendai NP324–332-vaccinated or unvaccinated control animals as determined by a Student t test (P < 0.05).

Effects of dendritic cell vaccination against lytic cycle T-cell epitopes on the persistent phase of the MHV-68 infection.

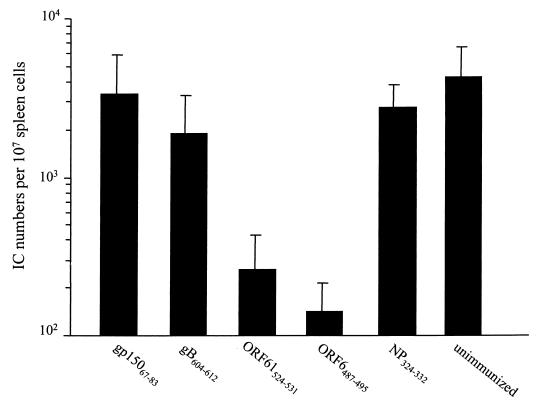

Previous studies have shown that after MHV-68 is cleared from the lung, the virus establishes latency in B cells, lung epithelium, and macrophages (37, 40, 46). The number of latently infected cells reaches the peak level of around 1:104 spleen cells at day 14 and subsequently declines to a stable level of approximately 1:106 spleen cells by day 21 (2, 40). The establishment of latency is associated with the development of an IM-like syndrome characterized by a high frequency of activated CD8+ and Vβ4+/CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood and spleen (2, 40). Thus, we next asked whether the reduction in viral load during the acute phase of the infection that resulted from vaccination had an impact on the establishment of latency and the development of the IM-like syndrome. The numbers of latently infected cells in the spleens of infected animals were determined in an infective center assay. As shown in Fig. 5, the numbers of latently infected cells at day 14 were significantly (approximately 10-fold) reduced in mice that had been vaccinated with the ORF6487–495 or ORF61524–531 peptides compared to the control (P < 0.05 in a Student t test). Thus, the impact of vaccination on the acute phase of the response also resulted in partial control of the development of latent infection. In contrast, the numbers of latently infected cells were not reduced in mice that had been vaccinated with either the subdominant gB604–612 peptide or the I-Ab-restricted gp15067–83 peptide. Interestingly, the reduction in peak latency in each group of vaccinated animals correlates with the reduction in lung viral titers (compare Fig. 4 and 5). For example, vaccination with the ORF6487–495 or ORF61524–531 peptide, which resulted in the strongest reduction in viral load in the lung, also gave the strongest reduction in infective centers at day 14. However, despite the effect of some vaccination regimens on the peak number of latent cells, analysis of latency levels at later time points (beyond day 28) showed no difference between the groups (data not shown). The frequencies of latent cells in all groups at that time were about 1:105 spleen cells. Splenomegaly in infected mice at day 14 after infection also mirrored the infective centers numbers, inasmuch as spleens were significantly smaller in the ORF6487–495- and ORF61524–531-vaccinated animals than in the other groups (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that vaccination with some class I-restricted peptides had a dramatic impact on the peak numbers of latently infected cells but did not prevent the establishment of long-term viral latency.

FIG. 5.

Latently infected cells in the spleens at day 14 postinfection in C57BL/6 mice vaccinated with various epitopes. Numbers of latently infected spleen cells were measured by infective center (IC) assay as described in Materials and Methods. The results shown are the average and 1 standard deviation of four to seven mice in two independent experiments. The reduction in latently infected spleen cells in the ORF6487–495- and ORF61524–531-vaccinated animals were significantly different from either the Sendai NP324–332-vaccinated or unvaccinated control animals as determined by a Student t test (P < 0.05).

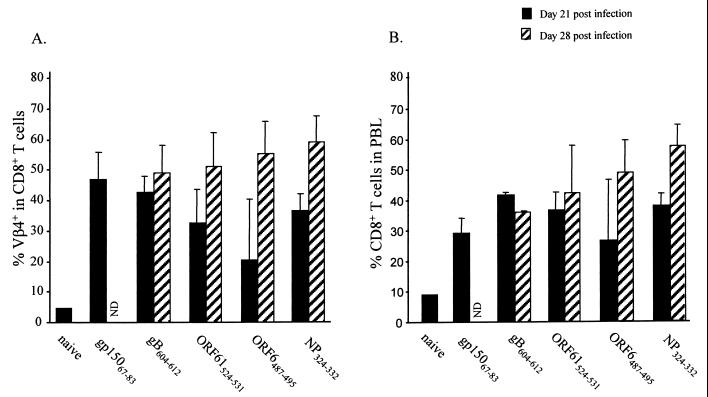

We also investigated the effect of peptide vaccination on the development of the IM-like syndrome. Previous studies have shown that the increase in CD8+ and Vβ4+/CD8+ numbers begins at day 18 and plateaus at around day 28 after infection (41). Thus, blood samples were taken from vaccinated mice at day 21 and day 28 after MHV-68 infection and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the numbers of Vβ4+/CD8+ and CD8+ T cells. As shown in Fig. 6, the development of IM-like syndrome was not affected by vaccination inasmuch as there was normal expansion of Vβ4+/CD8+ and CD8+ T cells in both vaccinated and control mice. Thus, the data indicate that the reduction in viral titers during the acute phase and the reduction in the numbers of latently infected cells in vaccinated mice did not prevent or delay the development of IM.

FIG. 6.

Vβ4+/CD8+ T-cell expansion in C57BL/6 mice vaccinated with various epitopes. Mice were vaccinated with the indicated peptides and then subsequently infected with MHV-68. Blood samples were taken at day 21 or day 28 after MHV-68 infection. After erythrocyte lysis, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the frequency of Vβ4+ cells among CD8+ T cells (A) or CD8+ cells among total peripheral blood cells (B). Data show averages of three to five mice, and error bars show 1 standard deviation. Unvaccinated naive mice were included as an additional control. ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of human diseases associated with γHV infections has led to significant interest in developing vaccines that control this class of viral infections. An optimal vaccine must not only control of the initial infection but also block the subsequent establishment of latency. In this study, we investigated whether vaccines designed to promote antiviral T-cell responses could affect the course of MHV-68 infection. The rationale was that T-cell responses targeted to antigenic lytic cycle viral proteins might reduce the viral load to a level that latency could not be established. The data show that vaccination with either MHC class I- or class II-restricted lytic-phase T-cell epitopes significantly reduced viral titers during the acute infection. Moreover, the peak of latently infected spleen cells was significantly reduced following vaccination with immunodominant CD8+ T-cell epitopes. Thus, these data demonstrate that T-cell vaccination can alter the course of MHV-68 infection and show that vaccines using γHV CTL epitopes are practical and promising. However, this vaccination approach did not prevent the establishment of long-term latency and the development of the IM-like syndrome, suggesting that stronger control of the initial infection might be essential to prevent the establishment of latency. Alternatively, an immune response directed to the latency-associated antigens may be required to abrogate the latent infection. These data also demonstrate the utility of using dendritic cells as a vaccination vehicle and are consistent with studies showing that mice immunized with peptide-loaded dendritic cells were fully protected against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus challenge (23). The advantage of this approach is its efficacy and the fact that it avoids the complications associated with the use of adjuvants.

The CD8+ T-cell response has been shown to be the primary mechanism for controlling the acute phase of a primary MHV-68 infection (2, 9). This response is dominated by T cells specific for the ORF61524–531/Kb and ORF6487–495/Db epitopes, which account for around 50% of total CD8+ T cells in the lung during the peak of the infection (33). Vaccination against these epitopes led to a reduction in peak viral titers of up to 100-fold in the lung and demonstrated the potential of this approach in controlling the virus. Vaccination with the subdominant gB604–612/Kb epitope also led to a variable degree of protection, which probably reflected the efficiency of vaccination in individual animals. However, despite the fact that vaccination had a significant impact on the virus level during acute infection, this approach did not completely prevent the establishment of the respiratory infection. This is consistent with studies in other respiratory virus models, such as influenza and Sendai viruses, which have shown that primed CD8+ CTL have a limited protective effect on the acute infection by reducing peak viral load (4, 49). This probably reflects the fact that even recall CD8+ T-cell responses require several days to develop giving the virus time to replicate.

Interestingly, there appears to be a correlation between the viral load in the lung and the peak numbers of latently infected cells in mice vaccinated with MHC class I-restricted peptides. Thus, a reduction in the number of viral particles in the lung resulted in fewer latently infected spleen cells at day 14. The reduction in latently infected cells correlated with a reduction in splenomegaly (data not shown), similar to that observed after CD4+ T cell depletion (43), thus reinforcing the idea that the rise in latently infected cells and splenomegaly are intimately linked. Since CD8+ T cells are the predominant effectors for viral clearance from the lung, these data demonstrated that CD8+ T-cell vaccination could have a significant impact on the development of a latent infection. However, long-term latency was not affected in vaccinated animals, demonstrating that the virus was able to efficiently establish a persistent infection despite strong immunological control of the respiratory infection. These data are very similar to those obtained when animals were primed with vacgp150 to generate a neutralizing anti-gp150 antibody response (36). In both studies, the peak number of latently infected cells was reduced, but long-term latency was not prevented. It is likely that this vaccination strategy also resulted in a reduction of viral load in the lungs but could not prevent infection of at least some B cells. Based on our understanding of EBV infections in humans, it is possible that there is an expansion of latently infected B cells, and the numbers of these cells may be controlled by independent homeostatic mechanisms (29). Infection of just a few B cells may be sufficient to establish the fully latent state, suggesting that stronger control of the primary infection will be necessary for complete protection. This may be achieved by improving the vaccination strategy to increase the vigor of the CTL response against lytic epitopes. Alternatively, the vaccine could be formulated to include antigens that are expressed in latently infected cells to provide a second layer of protection. In this regard, we have recently shown that the M2 protein of MHV-68 is expressed in latently infected cells and further identified a CD8+ T-cell epitope in this protein (14).

A key characteristic of MHV-68 infection in mice is the IM syndrome, which is similar to that observed following EBV infection of humans (29). The syndrome is characterized by increased numbers of activated CD8+ T cells in the blood and spleen which appear at about day 18 (after lytic virus in the lung has been cleared) and reach maximal levels after 28 days (41). Some, but not all, of these cells appear to be virus specific (33). Moreover, we have shown that a substantial fraction of these cells express the Vβ4 T-cell receptor element, irrespective of the MHC haplotype (8, 41). The mechanism underlying the Vβ4+/CD8+ T-cell expansion is not understood, although there is evidence to suggest that it correlates with the establishment of latent infection. For example, mouse strains that do not establish a latent infection in B cells (e.g., B-cell-deficient mice) do not develop the IM syndrome, despite the fact that there is a robust lytic infection in the lung (44). Vaccination of the mice with lytic cycle epitopes had no detectable effect on the development of IM or the expansion of Vβ4+/CD8+ T cells, consistent with the fact that long-term latency was established in these animals. In addition, the lack of an effect on the Vβ4+/CD8+ T cell expansion is consistent with data suggesting that this is driven by nonconventional antigens (8, 41).

It was interesting that vaccination with a CD4+ T-cell epitope resulted in a substantial reduction of the viral load in the lungs of MHV-68-infected mice. At this point it is not clear whether this protection reflects a direct effect of primed CD4+ T cells (such as cytokine secretion or lytic activity) (5, 13), enhanced CD8+ T-cell response, or accelerated antibody production to the virus. It is also possible that the vaccination strategy induced protective anti-gp15067–83 peptide antibodies since the peptide defined a helper T-cell epitope (1, 21). However, the use of peptides loaded onto dendritic cells should greatly minimize the possibility that anti-gp150 peptide antibodies are being generated during the vaccination. Although vaccination with the gp15067–83 peptide resulted in a reduced viral load in the lung, there was no subsequent effect on the peak numbers of latently infected cells in the spleen as had been seen in the mice vaccinated with the class I-restricted peptides. This is in contrast to the data reported by Stewart et al. (36), showing that vac-gp150 was effective at reducing both splenomegaly and the number of infective centers in the spleen. However, it is likely that the vac-gp150 vaccine induced a neutralizing antibody response, which may account for the difference between the two studies. Alternatively, the vaccinia virus approach may induce stronger T-cell immunity to the gp150 protein, resulting in protection better than that observed using dendritic cells. Previous studies have shown that mice lacking CD4+ T cells initially control the acute infection but are unable to control the virus long term, resulting in a lethal resurgence of lytic viruses in the respiratory tract (2, 37). Moreover, MHV-68-specific CD4+ T-cell memory seems to be sustained for the long term in fully immunocompetent mice (5, 6). Thus, virus-specific CD4+ T cells may be required to maintain effective CD8+ T-cell-mediated control of persistent MHV-68 infection. In this context, the differential control of the acute infection and the initial peak of latency may reflect differences in the level of help required for CD8+ T-cell control of these two stages of the infection.

In summary, the current data show that CD8+ peptide vaccination can have a significant impact on the early stages of a γHV infection. In addition to a substantial reduction in the viral load during the acute phase of the infection, there was a significant reduction in the peak numbers of latent cells. However, this approach did not prevent the long-term establishment of latency. Thus, protection against this class of viruses may require vaccination strategies that can utilize all the three arms of host defense system and target both lytic- and latent-phase antigens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anne-Marie Hamilton-Easton and Richard Cross for assistance with flow cytometry, Tony Caver for help with dendritic cell cultures, and Sherri Surman and Twala Hogg for technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI37597 (to D.L.W.), AI42947 (to M.A.B.), P30 CA21765 (Cancer Center Support CORE grant), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beachey E H, Seyer J M, Dale J B, Simpson W A, Kang A H. Type-specific protective immunity evoked by synthetic peptide of Streptococcus pyogenes M protein. Nature. 1981;292:457–459. doi: 10.1038/292457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardin R D, Brooks J W, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of a gamma-herpesvirus in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:863–871. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin M S, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles D M, Moore P S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Webster R G, Woodland D L. Induction of CD8+ T cell responses to dominant and subdominant epitopes and protective immunity to Sendai virus infection by DNA vaccination. J Immunol. 1998;160:2425–2432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen J P, Cardin R D, Branum K C, Doherty P C. CD4+ T cell mediated control of a γ-herpesvirus in B cell-deficient mice is mediated by IFN-γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5135–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen J P, Doherty P C. Quantitative analysis of the acute and long-term CD4+ T-cell response to a persistent gammaherpesvirus. J Virol. 1999;73:4279–4283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4279-4283.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole G A, Clements V K, Garcia E P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Allogeneic H-2 antigen expression is insufficient for tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8613–8617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coppola M A, Flano E, Nguyen P, Hardy C L, Cardin R D, Shastri N, Woodland D L, Blackman M A. Apparent MHC-independent stimulation of CD8+ T cells in vivo during latent murine gammaherpesvirus infection. J Immunol. 1999;163:1481–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehtisham S, Sunil-Chandra N P, Nash A A. Pathogenesis of murine gammaherpesvirus infection in mice deficient in CD4 and CD8 T cells. J Virol. 1993;67:5247–5252. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5247-5252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein M A, Morgan A J, Finerty S, Randle B J, Kirkwood J K. Protection of cottontop tamarins against Epstein-Barr virus-induced malignant lymphoma by a prototype subunit vaccine. Nature. 1985;318:287–289. doi: 10.1038/318287a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finerty S, Mackett M, Arrand J R, Watkins P E, Tarlton J, Morgan A J. Immunization of cottontop tamarins and rabbits with a candidate vaccine against the Epstein-Barr virus based on the major viral envelope glycoprotein gp340 and alum. Vaccine. 1994;12:1180–1184. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grusby M J, Johnson R S, Papaioannou V E, Glimcher L H. Depletion of CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Science. 1991;253:1417–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.1910207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou S, Doherty P C, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R, Katz J M. Delayed clearance of Sendai virus in mice lacking class I MHC-restricted CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:1319–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husain S M, Usherwood E J, Dyson H, Coleclough C, Coppola M A, Woodland D L, Blackman M A, Stewart J P, Sample J T. Murine gammaherpesvirus M2 gene is latency-associated and its protein a target for CD8+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7508–7513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman R M. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba K, Metlay J P, Crowley M T, Steinman R M. Dendritic cells pulsed with protein antigens in vitro can prime antigen-specific, MHC-restricted T cells in situ. J Exp Med. 1990;172:631–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaba K, Young J W, Steinman R M. Direct activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1987;166:182–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappler J W, Skidmore B, White J, Marrack P. Antigen-inducible, H-2-restricted, interleukin-2-producing T cell hybridomas. Lack of independent antigen and H-2 recognition. J Exp Med. 1981;153:1198–1214. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karttunen J, Shastri N. Measurement of ligand-induced activation in single viable T cells using the lacZ reporter gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3972–3976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna R, Burrows S R, Kurilla M G, Jacob C A, Misko I S, Sculley T B, Kieff E, Moss D J. Localization of Epstein-Barr virus cytotoxic T cell epitopes using recombinant vaccinia: implications for vaccine development. J Exp Med. 1992;176:169–176. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerner R A, Green N, Alexander H, Liu F T, Sutcliffe J G, Shinnick T M. Chemically synthesized peptides predicted from the nucleotide sequence of the hepatitis B virus genome elicit antibodies reactive with the native envelope protein of Dane particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3403–3407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, Flano E, Usherwood E J, Surman S, Blackman M A, Woodland D L. Lytic cycle T cell epitopes are expressed in two distinct phases during MHV-68 infection. J Immunol. 1999;163:868–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludewig B, Ehl S, Karrer U, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Dendritic cells efficiently induce protective antiviral immunity. J Virol. 1998;72:3812–3818. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3812-3818.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss D J, Schmidt C, Elliott S, Suhrbier A, Burrows S, Khanna R. Strategies involved in developing an effective vaccine for EBV-associated diseases. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;69:213–245. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murali-Krishna K, Altman J D, Suresh M, Sourdive D J, Zajac A J, Miller J D, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nash A A, Sunil-Chandra N P. Interactions of the murine gammaherpesvirus with the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:560–563. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Roby C, Clements V K, Cole G A. Tumor-specific immunity can be enhanced by transfection of tumor cells with syngeneic MHC-class-II genes or allogeneic MHC-class-I genes. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1991;6:61–68. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rammensee H G, Friede T, Stevanoviic S. MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics. 1995;41:178–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00172063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickinson A B, Moss D J. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:405–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanderson S, Shastri N. LacZ inducible, antigen/MHC-specific T cell hybrids. Int Immunol. 1994;6:369–376. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steven N M, Annels N E, Kumar A, Leese A M, Kurilla M G, Rickinson A B. Immediate early and early lytic cycle proteins are frequent targets of the Epstein-Barr virus-induced cytotoxic T cell response. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1605–1617. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevenson P G, Belz G T, Altman J D, Doherty P C. Changing patterns of dominance in the CD8+ T cell response during acute and persistent murine γ-herpesvirus infection. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199904)29:04<1059::AID-IMMU1059>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart J P, Janjua N J, Pepper S D, Bennion G, Mackett M, Allen T, Nash A A, Arrand J R. Identification and characterization of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 gp150: a virion membrane glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:3528–3535. doi: 10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00034574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart J P, Janjua N J, Sunil-Chandra N P, Nash A A, Arrand J R. Characterization of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 glycoprotein B (gB) homolog: similarity to Epstein-Barr virus gB (gp110) J Virol. 1994;68:6496–6504. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6496-6504.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart J P, Micali N, Usherwood E J, Bonina L, Nash A A. Murine gamma-herpes 68 glycoprotein 150 protects against virus-induced mononucleosis: a model system for gammaherpesvirus vaccination. Vaccine. 1999;17:152–157. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart J P, Usherwood E J, Ross A, Dyson H, Nash T. Lung epithelial cells are a major site of murine gammaherpesvirus persistence. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1941–1951. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sunil-Chandra N P, Arno J, Fazakerley J, Nash A A. Lymphoproliferative disease in mice infected with murine gammaherpesvirus 68. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:818–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sunil-Chandra N P, Efstathiou S, Arno J, Nash A A. Virological and pathological features of mice infected with murine gamma-herpesvirus 68. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2347–2356. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-9-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sunil-Chandra N P, Efstathiou S, Nash A A. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 establishes a latent infection in mouse B lymphocytes in vivo. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3275–3279. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tripp R A, Hamilton-Easton A M, Cardin R D, Nguyen P, Behm F G, Woodland D L, Doherty P C, Blackman M A. Pathogenesis of an infectious mononucleosis-like disease induced by a murine gamma-herpesvirus: role for a viral superantigen? J Exp Med. 1997;185:1641–1650. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Usherwood E J, Hogg T L, Woodland D L. Enumeration of antigen-presenting cells in mice infected with Sendai virus. J Immunol. 1999;162:3350–3355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usherwood E J, Ross A J, Allen D J, Nash A A. Murine gammaherpesvirus-induced splenomegaly: a critical role for CD4 T cells. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:627–630. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-4-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Usherwood E J, Stewart J P, Robertson K, Allen D J, Nash A A. Absence of splenic latency in murine gammaherpesvirus 68-infected B cell-deficient mice. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2819–2825. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Virgin H W, Latreille P, Wamsley P, Hallsworth K, Weck K E, Dal Canto A J, Speck S H. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol. 1997;71:5894–5904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5894-5904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weck K E, Kim S S, Virgin H W, Speck S H. Macrophages are the major reservoir of latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 in peritoneal cells. J Virol. 1999;73:3273–3283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3273-3283.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White J, Blackman M, Bill J, Kappler J, Marrack P, Gold D P, Born W. Two better cell lines for making hybridomas expressing specific T cell receptors. J Immunol. 1989;143:1822–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woodland D, Happ M P, Bill J, Palmer E. Requirement for cotolerogenic gene products in the clonal deletion of I-E reactive T cells. Science. 1990;247:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.1968289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodland D L, Cole G A, Doherty P C. Viral immunity and vaccine strategies. In: Kaufmann S H E, editor. Concepts in vaccine development. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]